Abstract

Myelodysplastic syndromes represent a group of heterogeneous hematopoietic neoplasms derived from an abnormal multipotent progenitor cell, characterized by a hyperproliferative bone marrow, dysplasia of the cellular hemopoietic elements and ineffective erythropoiesis. Anemia is a common finding in myelodysplastic syndrome patients, and blood transfusions are the only therapeutic option in approximately 40% of cases. The most serious side effect of regular blood transfusion is iron overload.

Currently, cardiovascular magnetic resonance using T2 is routinely used to identify patients with myocardial iron overload and to guide chelation therapy, tailored to prevent iron toxicity in the heart. This is a major validated non-invasive measure of myocardial iron overloading and is superior to surrogates such as serum ferritin, liver iron, ventricular ejection fraction and tissue Doppler parameters.

The indication for iron chelation therapy in myelodysplastic syndrome patients is currently controversial. However, cardiovascular magnetic resonance may offer an excellent non-invasive, diagnostic tool for iron overload assessment in myelodysplastic syndromes. Further studies are needed to establish the precise indications of chelation therapy and the clinical implications of this treatment on survival in myelodysplastic syndromes.

Keywords: Myelodysplastic syndromes, Blood transfusion, Iron overload, Magnetic

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) comprises an acquired primitive stem cell disorder resulting in ineffective hematopoiesis manifested by variable degrees and numbers of cytopenias, as well as an increased risk of transformation to acute leukemia. MDS is relatively common with a reported incidence of 3.5–4.9 per 100,000 people.1 The incidence increases to 28–36 per 100,000 in over 80-year-old individuals, making it as common as myeloma in this age group.2 Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions comprise the most effective treatment of anemia in MDS patients, in the expense of organ damaging iron overload.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been successfully used for the evaluation of myocardial and liver iron overload. MRI is the only technique able to provide non-invasive information about iron overload, as well as microcirculation defects and the detection of myocardial scars.

Myelodysplastic syndromes

MDS represent a group of heterogeneous hematopoietic disorders derived from an abnormal multipotent progenitor cell, characterized by a hyperproliferative bone marrow, dysplasia of the cellular hemopoietic elements, and ineffective hematopoiesis (Figure 1). Peripheral blood cytopenias and marked morphologic dysplasias are prominent and ineffective erythropoiesis results in symptomatic anemia.3 Cellular dysfunction results in an increased risk of infection, bleeding tendency due to thrombocytopenia, and need for transfusions in most MDS patients.4 MDS can be classified as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (therapy-related), the latter being associated with prior radiotherapy, chemotherapeutic agents, and immunosuppression therapy.5 Other risk factors for MDS development include benzene exposure, occupational chemicals, tobacco exposure, excessive alcohol, viral infections, and autoimmune disorders, as well as chronic inflammation.5 A useful classification of MDS according to their pathogenesis, cytological features and specific karyotypes, was proposed initially by the French-American-British (FAB) Cooperative Study Group.6 More recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) worked out an updated classification that represents an extension of the FAB proposal, with several modifications.7 Alterations in many individual biological pathways have been implicated in MDS pathophysiology. However, the primary hypothesis involves an initial deleterious genetic event within a hematopoietic stem cell, subsequent development of excessive cytokines/inflammatory response leading to a proapoptotic/proliferative state, resulting in peripheral cytopenias despite a hypercellular bone marrow. Furthermore, the presence of detectable cytogenetic abnormalities in approximately 40–70% of patients with primary MDS and over 80% with secondary MDS, as well as the validated prognostic value of specific cytogenetic aberrations in MDS, supports the theory of an incidental genetic event.8

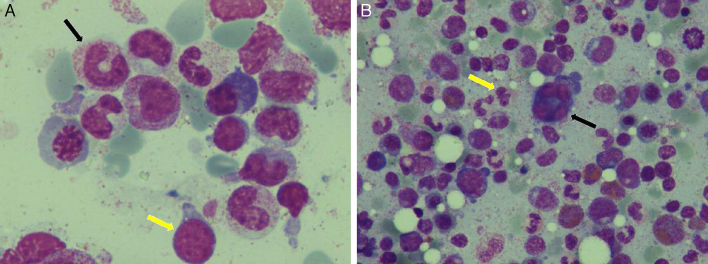

Figure 1.

Characteristic bone marrow films in myelodysplastic syndrome. (A) Giant granulocyte (black arrow) and blast cell (yellow arrow). (B) Dysplastic megakaryocyte with multiple separated nuclei (black arrow) and pseudo-Pelger cells (yellow arrow).

Images courtesy of Dr V. Karali (First Department of Propaedeutic and Internal Medicine, Athens University Medical School, Athens, Greece).

Anemia, transfusion and iron overload in myelodysplastic syndrome patients

A limited number of effective treatment options are available to treat anemia and thus help to prevent iron overload and other transfusion-related side effects in MDS patients. A direct approach is to correct anemia by administering hematopoietic growth factors, i.e. erythropoietin with or without granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF).9 Other drugs, such as lenalidomide, cyclosporine-A and antithymocyte globulin act in certain subgroups of MDS patients and may improve or correct anemia.10–12 Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the only curative approach.13

RBC transfusions are considered in MDS patients when hemoglobin (Hb) <8 g/dL, and may provide temporary relief from the symptoms of anemia, but they also add extra iron to the body.14 And while there are therapies, as mentioned above, that can restore the production of RBC so that patients can become transfusion independent, they are not effective in all MDS patients. In fact, for approximately 40% of MDS patients, transfusions are the only option to treat the symptoms of anemia.4

Supportive therapy with regular RBC transfusions can lead to elevated levels of iron in the blood and other tissues. The actual prevalence of iron overload in transfused MDS patients has not been systematically documented.15 Each unit of packed RBC contains about 250 mg of iron. As a general rule, iron overload occurs after the transfusion of 20 units of RBC.15 Thus, MDS patients who receive transfusions for their anemia are at risk for iron overload. In addition to iron overload as a result of multiple transfusions, MDS patients with sideroblastic anemia may develop iron overload subsequent to excessive absorption of iron from food.16

MDS patients considered to be eligible for iron chelation therapy are transplant recipient candidates. In recent years, different studies highlighted iron overload as a negative prognostic indicator in patients undergoing stem cell transplantation. In a cohort of 590 patients who underwent myeloablative stem cell transplantation, Armand et al. found a strong negative association between high serum ferritin levels and overall and disease-free survival. This association was seen in patients affected either by acute myeloid leukemia or MDS.17

Iron overload and survival in myelodysplastic syndrome

Transfusion dependency is associated with shortened overall survival and leukemia-free survival in MDS; however, it is not clear whether this effect is mediated by transfusional iron overload itself or if need for RBC transfusion is a marker of disease severity.18 The contribution of anemia itself to cardiac dysfunction in a predominantly older patient population as well as lack of consideration in the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) of the severity of anemia are confounding factors that make this evaluation difficult. Furthermore, worsening of survival with increasing serum ferritin values has been observed in patients with refractory anemia, refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts, and 5q-types of MDS, but not in patients with refractory cytopenia and multilineage dysplasia, suggesting that the longevity or other factors in patients with the aforementioned subtypes make them susceptible to the adverse effects of iron overload.19 However, it must be noted that all this evidence is indirect and large prospective studies that correlate accurate markers of iron overload, such MRI measurements of tissue iron and non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI)/labile plasma iron (LPI) with survival are necessary to conclusively determine the impact of iron overload on survival in MDS.

In addition to negatively impacting prognosis, anemia and transfusion dependence have significant impact on the quality of life of MDS patients. Despite the effects of anemia and transfusion dependence on disease outcomes and patient quality of life, the clinical impact of iron overload in MDS patients remains controversial.20 Studies of hereditary hemoglobinopathies (e.g. β-thalassemia) have shown causation for iron overload and organ toxicities.21 Clinical consequences of transfusion iron overload in non-thalassemic adults have been previously reported by Schafer et al.22 These authors also reported that long-term deferoxamine iron chelation therapy was effective not only in retarding but even reversing organ damage caused by parenchymal iron overload.23 However, evidence linking organ iron accumulation with morbidity in MDS is indirect. In a study of refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts, it was found that mild iron overload was common at presentation, but clinical manifestations occurred only in patients who had a regular need for RBC transfusions. Complications of iron overload were the most common causes of death.24 More recently, the effect of transfusion dependence and secondary iron overload on survival of MDS patients, classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, were also studied. Overall, transfusion dependence was found to significantly worsen the probability of survival and to increase the risk of progression to leukemia in MDS patients. An inverse relationship was observed between transfusions requirement and probability of survival. The negative impact of transfusion dependency was more pronounced in patients with refractory anemia, refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts and MDS with isolated deletion 5q. Overall, the most common non-leukemic cause of death was heart failure. Transfusional iron overload, as assessed by serum ferritin, was associated with worse survival in patients receiving regular RBC transfusions. The effect of iron overload was mainly noticeable among patients with refractory anemia, who have a median survival of more than five years and are more prone to develop long-term toxicity of iron overload.25 These observations indicate that the development of secondary iron overload per se worsens the survival of subgroups of transfusion dependent patients with MDS. Findings of a retrospective, single institution study suggest that iron overload significantly contributes to treatment related mortality in MDS. Finally, iron overload in MDS patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation may be associated with adverse outcomes.26

Small studies using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) techniques have shown variable and infrequent incidence of cardiac iron accumulation. Regardless of organ damage, iron overload may increase risk of infection by supplying readily available iron to support microorganism growth, while several retrospective studies have suggested that transfusion dependence influences subsequent overall survival and evolution to leukemia.27 Additional prospective trials using accurate iron overload markers are required to conclusively determine the impact of iron overload on overall survival in patients with MDS.

Management of transfusion-related iron overload in myelodysplastic syndrome patients

Iron overload therapeutic options can decrease transfusion needs as well as improve quality of life in MDS patients. Attainment of transfusion independence in the absence of cytogenetic responses with disease-modifying agents has been associated with improved overall survival.28 Patients who receive hypomethylating agents have demonstrated improvements in quality of life measures. Iron overload remains a risk for patients who have continued transfusion dependence even with hypomethylating therapy; therefore, iron chelation therapy may be recommended.29

By consensus, the following groups of MDS patients should be regarded as candidates for iron chelating therapy:

-

(i)

Patients with frank iron overload (e.g. stable/increasing serum ferritin >1000 ng/mL without signs of inflammation or liver disease), who are transfusion dependent (at any frequency) and have a life expectancy of at least one year.

-

(ii)

Transfusion dependent patients, who receive >2 RBC concentrates per month, at any ferritin level, and have a life expectancy of more than two years (exception: patients with frank iron deficiency, e.g. chronic gastrointestinal tract bleeding).

-

(iii)

In selected cases, iron chelating therapy can also be considered when life expectancy is less than two years. Examples are planned curative therapy (stem cell transplantation), massive iron overload with consecutive organopathy, or massive iron overload, judged to significantly reduce the quality of life. Additional parameters that may influence the decision to treat individual MDS patients with iron chelating agents are age (geriatric aspects), social and mental features, and comorbidity (organopathy).30

Cardiac iron in myelodysplastic syndromes

The organ damage of most concern, given the advanced age and comorbidities in many MDS patients is cardiac dysfunction resulting from myocardial iron deposition. Cardiac iron has been observed at autopsy in patients who have died of acute leukemia or other transfusion dependent anemias and correlates with the number of RBC transfusions; however these data are confounded by the contribution of anemia itself to cardiac dysfunction as well as the fact that transfusion dependence is a feature of disease severity in MDS.31 However, recent studies using the CMR T2 technique have shown that cardiac iron accumulation is quite variable but infrequent among patients with MDS. Moreover, cardiac iron in MDS patients does not correlate with serum ferritin or hepatic iron, but shows correlation with the chelatable iron pool as determined by urinary iron excretion, a surrogate for LPI.32 It remains to be determined whether LPI directly correlates with myocardial iron in MDS. Mechanisms leading to cardiac iron deposition in particular patients with lower grades of MDS, especially as it relates to hepcidin level, ineffective erythropoiesis, and elevated LPI, need further evaluation in larger studies.

Prospective studies correlating cardiac iron with cardiac function and survival as well as studies showing improvement in cardiac function with chelation will be necessary before averting or reversing cardiac dysfunction can be established as a primary goal of iron chelation in MDS.

Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of iron overload

MRI uses the magnetic properties of the human body to provide pictures of any tissue (Figure 2). Hydrogen nuclei are a principal constituent of body tissues in water and lipid molecules and produce a dipole moment (magnetic field) that can interact with an external magnetic field. MRI machines generate a strong, homogenous magnetic field by using a large magnet, made by passing an electric field through superconducting coils of wire. Hydrogen nuclei in the body, which normally have randomly oriented spins, when exposed to the magnetic field, align in a direction parallel to the magnetic field. The MRI machine applies short electromagnetic pulses at a specific radiofrequency (RF). The hydrogen nuclei absorb the RF energy and precess away from equilibrium. When the RF pulse is turned off, the precessing nuclei release the absorbed energy and return to normal. The strength of the signal varies, depending on the RF magnetic field applied. The examined tissue returns to normal in the longitudinal plane over a characteristic interval called T1 relaxation time. In the transverse plane, the return to normal occurs over a characteristic interval called T2 relaxation time. Using MRI, tissue iron is detected indirectly by the effects on relaxation times of ferritin and hemosiderin iron interacting with hydrogen nuclei. The presence of iron in the human body results in marked alterations of tissue relaxation times.33 While T1 decreases only moderately, T2 demonstrates a substantial decrease.34 Myocardial T2, a parameter measured by spin echo techniques, has been shown in experimental animals to have an inverse correlation with myocardial iron content.35 In a study by our group that compared myocardial T2 with iron content in heart biopsy, an agreement was found between myocardial biopsy and the MRI results.36 Unfortunately, the MRI signal is affected by multiple acquisition variables. Although T2 is relatively independent of field strength, there is an exception in the case of iron overload. In these patients, there is the linear dependence of T2 relaxivity (1/T2) on field strength.37

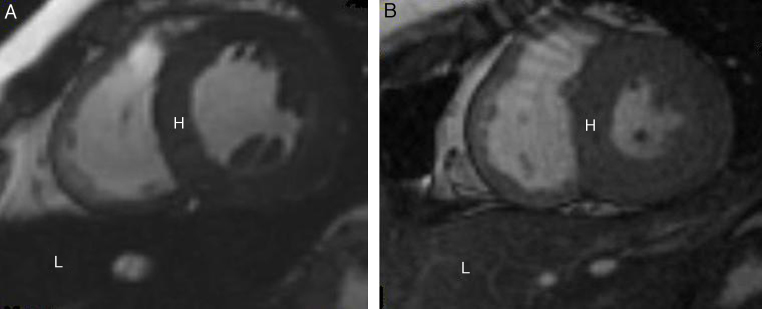

Figure 2.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance T2* images showing the heart (H) and liver (L) from two different patients at the same echo time (10.70 ms). (A) Dark signal indicating severe myocardial and liver siderosis. (B) Normal myocardial and liver signal suggesting mild iron deposition.

Images courtesy of Dr S. Mavrogeni (Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center, Athens, Greece).

Currently, CMR using T2 is routinely used in many countries to identify patients with myocardial iron overload and guide chelation therapy tailored to the heart. Myocardial T2 is calibrated to the myocardial iron concentration, and has been shown to improve with intensive iron chelation in parallel with the ejection fraction. Moreover, it is the major validated non-invasive measure of myocardial iron overload and is superior to surrogates such as serum ferritin, liver iron, ventricular ejection fraction and tissue Doppler parameters.38,39 Assessment of cardiac iron by MRI susceptometry has also been validated, although availability of the technique is limited.40 In most cases, chronic myocardial siderosis is both preventable and reversible with modern chelation regimes.41 Progress has also been made in the treatment of acute heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction.42 A substantial 71% decrease in deaths has been observed in the UK thalassemia cohort since the introduction of T2 CMR and improved iron chelation treatment.43 Other countries have also reported important amelioration in management of cardiac iron using T2 CMR.44,45 According to recent data, there is a substantial prevalence of myocardial iron overload in a large international sample of thalassemia major (TM) patients, who are regularly transfused and taking iron chelation therapy. The use of the threshold of T2 = 10 ms, below which the risk of cardiac complications rises significantly, has been already confirmed and alternative explanations for heart failure apart from myocardial iron overload seem unusual. The findings from independent centers worldwide indicate that myocardial T2 is a robust clinical tool with potential for further expansion to guide chelation regimes which are tailored to prevent the development of heart failure and prolong survival.46

Consequences of iron deposition in myelodysplastic syndromes

MRI has already been used for the evaluation of myocardial and liver iron overload in MDS. In a study by our group, after comparison of a population of patients with MDS and TM without evidence of heart failure using MRI, we identified that MDS patients, who received a higher amount of blood transfusions for longer time presented the same MRI pattern in both liver and heart as TM patients. On the contrary, MDS patients who received a lower amount of RBC transfusions for shorter time had no evidence of myocardial iron. However, they still had hepatic siderosis, because liver is the first affected organ in iron overload. Additionally, these patients had higher cardiac indices indicative of high output state, due to chronic anemia.47

Similar findings were also documented in other patient groups with less frequent transfusions compared to TM, but similar to patients with thalassemia intermedia and sickle cell disease.48 Recent reports have also assessed hepatic siderosis without evidence of heart iron overload in these patients. Additionally, ferritin reflects the total body iron and not the iron in individual organs, as has been already described in previous studies.49 These findings further emphasize the necessity of MRI in the evaluation of iron load, particularly after recent publications proving the significance of iron in MDS prognosis and treatment.

Clinical implications of magnetic resonance imaging findings in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes

The iron overload assessment may have serious clinical implications in MDS.

In a five-year prospective registry that enrolled 600 lower risk MDS patients with transfusional iron overload, clinical outcomes were compared between chelated and non-chelated patients. At baseline, cardiovascular comorbidities were more common in non-chelated patients. At 24 months, chelation was associated with longer median overall survival (52.2 months vs. 104.4 months; p-value <0.0001) and a trend toward longer leukemia-free survival and fewer cardiac events. No difference in safety was documented between groups.48 Finally, a recent study showed that deferasirox was well tolerated and effective in reducing S-ferritin and liver iron concentration (LIC) level in transfusional iron overload MDS patients or aplastic anemia.49 Therefore, iron chelation treatment should be considered in transfused MDS patients when transfusion related iron overload is documented.

Based on available data, the Expert Panel of the Italian Society of Hematology agreed that iron chelation with deferoxamine should be considered as a therapy for MDS patients, who have previously received more than 50 RBC units and for whom a life span longer than six months is expected.50 The Expert Panel of the British Society of Hematology concluded that iron chelation should be considered once a patient has received 25 RBC units, but only in patients for whom long-term transfusion therapy is likely, such as those with pure sideroblastic anemia or the 5q-syndrome and deferoxamine 20–40 mg/kg should be administered by 12 h subcutaneous (sc) infusion 5–7 days per week.51

The choice between deferoxamine and deferasirox is controversial. Although deferoxamine is effective and relatively safe (ocular and ear toxicity have been described), it requires subcutaneous administration which is uncomfortable for many patients. As an oral drug, deferasirox is easier for patients, but its long-term effectiveness and safety have not been defined. Deferoxamine should be employed before allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Whether or not prevention of severe iron overload by chelation will result in lower morbidity and mortality in regularly transfused MDS remains to be proven. In a comparative study of deferasirox and deferiprone in the treatment of iron overload in MDS patients, the incidence of adverse effects (mostly gastrointestinal symptoms) was similar after administration of both drugs. The symptoms of deferasirox toxicity were mild and mostly transient and no drug-related myelosuppressive effect was observed in contrast to deferiprone, where agranulocytosis occurred in 4% of patients and the treatment had to be discontinued due to side effects in 20% of patients. The results confirmed the usefulness of deferasirox as an effective and safe iron chelator in MDS patients and indication of deferiprone as an alternative treatment only in patients with mild or moderate iron overload clearly not indicated for deferasirox.52

Conclusion

In conclusion, the MRI imaging pattern of the liver and heart in MDS shows that iron overload plays a crucial role in myocardial and hepatic pathophysiology of these patients and may also influence MDS survival. However, further studies are needed in order to identify the threshold for transfusions in respect to provoking myocardial and hepatic iron deposition and the role of chelation in the long-term prognosis of MDS patients.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Neukirchen J., Schoonen W.M., Strupp C., Gattermann N., Aul C., Haas R. Incidence and prevalence of myelodysplastic syndromes: data from the Düsseldorf MDS-registry. Leuk Res. 2011;35(12):1591–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aul C., Giagounidis U., Germing U. Epidemiological features of myelodysplastic syndrome: results from regional cancer surveys and hospital-based statistics. Int J Hematol. 2001;73(4):405–410. doi: 10.1007/BF02994001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warlick E.D., Smith B.D. Myelodysplastic syndromes: review of pathophysiology and current novel treatment approaches. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7(6):541–558. doi: 10.2174/156800907781662284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazzola M., Della Porta M.G., Malcovati L. Clinical relevance of anemia and transfusion iron overload in myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008;(1):166–175. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalamaga M., Petridou E., Cook F.E., Trichopoulos D. Risk factors for myelodysplastic syndromes: a case–control study in Greece. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(7):603–608. doi: 10.1023/a:1019573319803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennet J.M., Catovsky D., Daniel M.T., Flandrin G., Galton D.A., Gralnick H.R. Proposals for the classification of the myelosysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 1982;51(2):189–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunning R.D., Orazi A., Germing U., Le Beau M.M., Porwit A., Baumann I. Myelodysplastic syndromes/neoplasms, overview. In: Swerdlow S.H., Campo E., Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Pileri S.A., Stein H., editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC Press; Lyon: 2008. pp. 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olney H.J., Le Beau M.M. The cytogenetics of myelodysplastic syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2001;14(3):479–495. doi: 10.1053/beha.2001.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jädersten M., Montgomery S.M., Dybedal I., Porwit-MacDonald A., Hellström-Lindberg E. Long-term outcome of treatment of anemia in MDS with erythropoietin and G-CSF. Blood. 2005;106(3):803–811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.List A., Kurtin S., Roe D.J., Buresh A., Mahadevan D., Fuchs D. Efficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):549–557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issa J.P., Garcia-Manero G., Giles F.J., Mannari R., Thomas D., Faderl S. Phase 1 study of low-dose prolonged exposure schedules of the hypomethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) in hematopoietic malignancies. Blood. 2004;103(5):1635–1640. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molldrem J.J., Caples M., Mavroudis D., Plante M., Young N.S., Barret A.J. Antithymocyte globulin for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 1997;99(3):699–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.4423249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutler C. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010(1):325–329. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barzi A., Sekeres M.A. Myelodysplastic syndromes: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77(1):37–44. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.List A.F. Iron overload in myelodysplastic syndromes: diagnosis and management. Cancer Control. 2010;17(Suppl.):2–8. doi: 10.1177/107327481001701s01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuijpers M.L., Raymakers R.A., Mackenzie M.A., de Witte T.J., Swinkels D.W. Recent advances in the understanding of iron overload in sideroblastic myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(3):322–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armand P., Kim H.T., Cutler C.S., Ho V.T., Koreth J., Alyea E.P. Prognostic impact of elevated pretransplantation serum ferritin in patients undergoing myeloablative stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;109(10):4586–4588. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malcovati L., Porta M.G., Pascutto C., Invernizzi R., Boni M., Travaglino E. Prognostic factors and life expectancy in myelodysplastic syndromes classified according to WHO criteria: a basis for clinical decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(30):7594–7603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malcovati L. Impact of transfusion dependency and secondary iron overload on the survival of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2007;31(Suppl. 3):S2–S6. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(07)70459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah J., Kurtin S.E., Arnold L., Lindroos-Kolqvist P., Tinsley S. Management of transfusion-related iron overload in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16(Suppl):37–46. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.S1.37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu P., Henkelman M., Joshi J., Hardy P., Butany J., Iwanochko M. Quantification of cardiac and tissue iron by nuclear magnetic resonance relaxometry in a novel murine thalassemia-cardiac iron overload model. Can J Cardiol. 1996;12(2):155–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schafer A.I., Cheron R.G., Dluhy R., Cooper B., Gleason R.E., Soeldner J.S. Clinical consequences of acquired transfusional iron overload in adults. N Engl J Med. 1981;304(6):319–324. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102053040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schafer A.I., Rabinowe S., Le Boff M.S., Bridges K., Cheron R.G., Dluhy R. Long-term efficacy of deferoxamine iron chelation therapy in adults with acquired transfusional iron overload. Adv Intern Med. 1985;145(7):1217–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roy N.B., Myerson S., Schuh A.H., Bignell P., Patel R., Wainscoat J.S. Cardiac ironoverload in transfusion-dependent patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(4):521–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pullarkat V. Objectives of iron chelation therapy in myelodysplastic syndromes: more than meets the eye? Blood. 2009;114(26):5251–5255. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alessandrino E.P., Della Porta M.G., Bacigalupo A., Malcovati L., Angelucci E., Van Lint M.T. Prognostic impact of pre-transplantation transfusion history and secondary iron overload in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a GITMO study. Haematologica. 2010;95(3):476–484. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.011429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoen B. Iron and infection: clinical experience. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34(Suppl 2):30–34. doi: 10.1053/AJKD034s00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leitch H.A., Vickars L.M. Supportive care and chelation therapy in MDS: are we saving lives or just lowering iron? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:664–672. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santini V. Novel therapeutic strategies: hypomethylating agents and beyond. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2012;2012:65–73. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennet J.M. Consensus statement on iron overload in myelodysplastic syndromes. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(11):858–861. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buja L.M., Roberts W.C. Iron in the heart: etiology and clinical significance. Am J Med. 1971;51(2):209–221. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood J.C. Cardiac iron across different transfusion-dependent diseases. Blood Rev. 2008;22(Suppl 2):14–21. doi: 10.1016/S0268-960X(08)70004-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomori J.M., Grossman R.I., Drott H.R. MR relaxation times and iron content of thalassemic spleens: an in vitro study. Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150(3):567–569. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mavrogeni S.I., Gotsis E.D., Markussis V., Tsekos N., Politis C., Vretou E. T2 relaxation time study of iron overload in b-thalassemia. MAGMA. 1998;6(1):7–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02662506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson L.J., Holden S., Davis B., Prescott E., Charrier C.C., Bunce N.H. Cardiovascular T2-star (T2*) magnetic resonance for the early diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(23):2171–2179. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mavrogeni S.I., Markussis V., Kaklamanis L., Tsiapras D., Paraskevaidis I., Karavolias G. A comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and cardiac biopsy in the evaluation of heart iron overload in patients with beta-thalassemia major. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75(3):241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carpenter J.P., He T., Kirk P., Roughton M., Anderson L.J., de Noronha S.V. On T2* magnetic resonance and cardiac iron. Circulation. 2011;123(14):1519–1528. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.007641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Telfer P.T., Prestcott E., Holden S., Walker M., Hoffbrand A.V., Wonke B. Hepatic iron concentration combined with long-term monitoring of serum ferritin to predict complications of iron overload in thalassaemia major. Br J Haematol. 2000;110(4):971–977. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leonardi B., Margossian R., Colan S.D., Powell A.J. Relationship of magnetic resonance imaging estimation of myocardial iron to left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in thalassemia. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1(5):572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z.J., Fischer R., Chu Z., Mahoney D.H., Jr., Mueller B.U., Muthupillai R. Assessment of cardiac iron by MRI susceptometry and R2* in patients with thalassemia. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;28(3):363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson L.J., Westwood M.A., Holden S., Davis B., Prescott E., Wonke B. Myocardial iron clearance during reversal of siderotic cardiomyopathy with intravenous desferrioxamine: a prospective study using T2* cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Br J Haematol. 2004;127(3):348–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolnagou A., Economides C., Eracleous E., Kontoghiorghes G.J. Long term comparative studies in thalassemia patients treated with deferoxamine or a deferoxamine/deferiprone combination Identification of effective chelation therapy protocols. Hemoglobin. 2008;32(1–2):41–47. doi: 10.1080/03630260701727085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Modell B., Khan M., Darlison M., Westwood M.A., Ingram D., Pennell D.J. Improved survival of thalassaemia major in the UK and relation to T2* cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2008;10:42. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pathare A., Taher A., Daar S. Deferasirox (Exjade) significantly improves cardiac T2* in heavily iron-overloaded patients with beta-thalassemia major. Ann Hematol. 2010;89(4):405–409. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0838-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ladis V., Chouliaras G., Berdoukas V., Chatziliami A., Fragodimitri C., Karabatsos F. Survival in a large cohort of Greek patients with transfusion-dependent beta thalassaemia and mortality ratios compared to the general population. Eur J Haematol. 2011;86(4):332–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carpenter J.P., Roughton M., Pennell D.J. International survey of T2* cardiovascular magnetic resonance in β-thalassemia major. Haematologica. 2013;98(9):1368–1374. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.083634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mavrogeni S., Gotsis E., Ladis V., Berdousis E., Verganelakis D., Toulas P. Magnetic resonance evaluation of liver and myocardial iron deposition in thalassemia intermedia and b-thalassemia major. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;24(8):849–854. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyons R.M., Marek B.J., Paley C., Esposito J., Garbo L., DiBella N. Comparison of 24-month outcomes in chelated and non-chelated lower-risk patients with myelodysplastic syndromes in a prospective registry. Leuk Res. 2014;38(2):149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheong J.W., Kim H.J., Lee K.H., Yoon S.S., Lee J.H., Park H.S. Deferasirox improves hematologic and hepatic function with effective reduction of serum ferritin and liver iron concentration in transfusional iron overload patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or aplastic anemia. Transfusion. 2013;54(6):1542–1551. doi: 10.1111/trf.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alessandrino E.P., Amadori S., Barosi G., Cazzola M., Grossi A., Liberato L.N. Italian Society of Hematology Evidence- and consensus-based practice guidelines for the therapy of primary myelodysplastic syndromes. A statement from the Italian Society of Hematology. Haematologica. 2002;87(12):1286–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowen D., Culligan D., Jowitt S., Kelsey S., Mufti G., Oscier D. UK MDS Guidelines Group Guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of adult myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2003;120(2):187–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cermak J., Jonasova A., Vondrakova J., Cervinek L., Belohlavkova P., Neuwirtova R. A comparative study of deferasirox and deferiprone in the treatment of iron overload in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2013;37(12):1612–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]