Abstract

Objectives

Intra-hepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is uncommon, but has severe effects on pregnancy outcomes. ICP is characterized by elevated serum bile acids and liver enzymes and preferentially affects women with liver disorders. We compared bile acids and pregnancy outcomes of HIV-infected pregnant women, who commonly have elevated live enzymes, with uninfected controls.

Methods

Twenty-four HIV-infected, including 2 co-infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and 25 uninfected women were tested during early and late pregnancy and postpartum.

Results

After exclusion of the HCV-infected women, serum bile acids were similar in HIV-infected and uninfected participants. -glutamyl transpeptidase was elevated in HIV-infected compared with uninfected women during pregnancy and postpartum. Bilirubin and aspartate transaminase were higher in uninfected compared with HIV-infected women in early pregnancy, but subsequently similar. Bile acids in late pregnancy correlated with bile acids in the baby at birth. An HIV- and HCV-co-infected pregnant woman with active hepatitis developed ICP complicated by fetal distress. Another co-infected participant without active hepatitis had an uneventful pregnancy and delivery.

Conclusion

In the absence of HCV co-infection, bile acid metabolism appeared to be similar in HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women. Both HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women had mild liver enzyme elevations.

Keywords: Intrahepatic cholestasis, Pregnancy, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Antiretroviral Therapy, Hepatitis C virus, Bile acids, Liver function

Introduction

Intra-hepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a clinical complication of pregnancy defined by pruritus without rash occasionally accompanied by jaundice and elevated liver enzymes. It typically arises in the second half of pregnancy and subsides after delivery. Although this disease is distressing to the gravida, it has minimal long-term effects on maternal health, but carries significant risks to the fetus including prematurity, low birth weight, intrapartum asphyxia [1] and increased fetal mortality. ICP is associated with a 1–60% risk of fetal demise [2].

Biochemically, ICP is characterized by increased levels of serum bile acids sometimes in association with elevated liver enzymes, consistent with a pathogenic mechanism of decreased hepatic excretion of bile acids [3,4]. Bile acids may increase 10 to 100 fold over normal levels [5,6]. The retained bile acids are purported to have a vaso-constrictive effect on the fetal blood circulation leading to the serious complications mentioned above [7]. ICP may cause placental alterations that reduce the ability of the fetus to dispose of bile acids, as evidenced by elevated bile acids in cord blood and meconium [8]. There is no universally accepted treatment of ICP. Diphenhydramine or other symptomatic medication has been used to control pruritus and cholestyramine or ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) have been recommended to increase intestinal excretion and decrease reabsorption of bile acids [9]. UDCA has been proposed as a therapeutic intervention, because it decreases serum bile acid levels, improves maternal symptoms of ICP, and may decrease the incidence of fetal adverse events [10,11]. Elective early term delivery is also suggested, because most of the fetal mortality associated with ICP condition occurs after week 37 [12].

The decreased hepatic excretion of bile acids, which represents the pathogenic mechanism of ICP, has been ascribed to hepatic effects of estrogen and progesterone metabolites, which are typically elevated in pregnancy [3,4]. Genetic and nutritional factors [13,14] and liver injury also play a role in this disease. As such, the incidence of ICP varies from 0.1%–0.2% in Europe and North America to 12%–22% in areas of South Asia and South America and first degree relatives of affected women have a 20-fold higher risk [7, 15]. HCV infection is associated with a 10-fold increase in the incidence of ICP over local background [16]; and elevated liver enzymes and/or total bilirubin are found in 30 to 50% of ICP cases [10,15].

HIV-infected pregnant women are subject to multiple hepatotoxic factors, which might affect their bile acid metabolism and increase their risk to develop ICP. Protease inhibitors (PI) commonly used for HIV therapy alter cytochrome P450 function, which is essential for normal enzymatic activity of the liver [17,18]. Some of the nucleoside (NRTI) and non-nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) also have hepatotoxic effects by different mechanisms [18]. Antiretroviral (ARV)-associated hepatotoxicity is particularly common in pregnant women [19]. HIV infection per se has been associated with hepatitis, particularly in advanced stages of the disease, and with fatty liver. In addition, the epidemiology of HIV infection makes HCV infection, alcohol abuse, and other drug use more common in these patients than in the general population, further contributing to the overall decreased liver reserve in HIV-infected individuals [20]. Data regarding ICP and pregnancies complicated by HIV infection is scarce. ICP is passively reported to the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry (), but bile acid metabolism has not been systematically studied in HIV-infected pregnant women.

To explore if HIV infection and its therapy may be associated with abnormal bile acid metabolism, we conducted a pilot study comparing serum bile acid levels of HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants with those of HIV-uninfected mother-infant dyads.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutions Review Board. HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women who consented to this study were enrolled between the years of 2005 and 2009. Exclusion criteria were acute hepatitis, liver failure, preeclampsia with liver dysfunction and severe systemic illness.

Design

Participants underwent an ICP-targeted questionnaire and physical exam and had bile acids, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and total bilirubin were measured at entry, during 2nd trimester and/or 3rd trimester if different from entry and 6 to 12 weeks after delivery. A standardized meal was administered 2 hours before each set of tests. Assays were performed in CLIA- and CAP-certified clinical laboratories using FDA-approved methods. Reference normal values were as established by Abbassi-Ghavanati et al. [21]. For HIV-infected pregnant women, CD4 cell numbers, plasma HIV RNA and antiretroviral information were abstracted from medical records. Concomitant medications were recorded both in HIV-infected and uninfected participants. Cord blood was collected for bile acid measurements. Newborn physical exam information was abstracted from the medical records.

Statistical analyses

Demographics, clinical characteristics at study entry and laboratory values at each time point were summarized and compared between HIV-negative and HIV-positive groups using two-sample t-tests for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical measures. Scatterplots and Spearman’s Correlation were used to assess the monotonic relationship between fold-difference from threshold AST, ALT, and GGT with bile acids.

Results

Demographic and HIV disease characteristics at entry

The study enrolled 24 HIV-infected and 25 uninfected pregnant women. An HIV-infected woman withdrew from the study after the first visit and was excluded from the analysis. Two of the HIV-infected women had anti-HCV antibodies and were analyzed separately, because they had an established ICP risk factor. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the remaining 46 subjects. There were no significant differences with respect to age, but there was an excess of black women in the HIV-infected compared with uninfected group. The parity was also significantly higher in HIV-infected compared with uninfected women. At entry, the 21 HIV-mono-infected participants were on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) including 2 NRTIs in all subjects plus PIs (protease inhibitor or principal investigator?) in 19 subjects and NNRTIs in another 2 subjects. The most commonly used PI was lopinavir co-formulated with ritonavir (N=11) followed by atazanavir with ritonavir boost (N=5) and nelfinavir (N=3). The plasma HIV RNA was undetectable (<50 copies/mL) in 14 participants (70%); six participants had mean (95% CI) log10 plasma HIV RNA 2.87 (1.86, 3.89); and one participant did not have the data recorded. The mean (95% CI) CD4 count was 609 (490; 728) cells/μL.

Table 1.

Entry Demographic and HIV Disease Characteristics.

| HIV positive (n= 21) | HIV negative (n=25) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age years (95% CI) | 28.2 (24.91, 31.49) | 30.4 (28.15, 32.72) | 0.247 |

| Mean week gestation (95% CI) | 25.9 (22.78, 29.03) | 19.9 (18.52, 21.29) | 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 10 (47%) | 19 (76%) | 0.259 |

| Hispanic | 5 (23%) | 4 (16%) | |

| Unknown | 6 (29%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Race | |||

| Not White | 8 (38%) | 0 | <.001 |

| White | 7 (33%) | 23 (88%) | |

| Unknown | 6 (29%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 6 (29%) | 23(88%) | <.001 |

| Multiparous | 7 (33%) | 1(4%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (38%) | 1(4%) | |

| HAART | |||

| Yes | 21 (100%) | ||

| HIV plasma RNA | |||

| <50 copies/mL | 14 (67%) | ||

| ≥50 copies/mL | 6 (29%) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (4%) | ||

| Mean Log10 Viral Load if not suppressed (95% CI) | 2.87 (1.86, 3.89) | ||

| Mean CD4 cells/mm3 (95% CI) | 609 (490, 728) |

Bile acids and liver function tests (LFT) in HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women

At entry [median (IQR) of 21.4 (19.5–24.5) weeks gestation], 7 of 20 HIV-infected and 10 of 23 uninfected pregnant women with available data had bile acid levels above the upper normal limit of the test for their gestational ages (Table 2). The geometric means of the serum bile acid concentrations did not differ significantly between the 2 groups. The highest level was observed in an HIV-infected subject at 23 μmol/L. At the last visit before delivery [median (IQR) of 36.0 (33.0–37.0) weeks gestation], 2 each HIV-infected and uninfected women had elevated bile acid levels for their gestational ages and the geometric means were also similar in the two groups. The highest bile acid level in late pregnancy of 22 μmol/L was observed in an uninfected asymptomatic woman. In the postpartum period [median (IQR) of 7.4 (5.6–12.1) weeks after delivery], 6 HIV-infected and 11 uninfected women had bile acid levels above the upper normal of non-pregnant women. Overall, only 1 HIV-infected and 1 uninfected woman had elevated bile acid levels at ≥ 2 visits.

Table 2.

Maternal bile acids and liver function values during pregnancy and post-partum.

| Geometric mean value (95% Confidence Interval) | Number above upper limit of normal/number evaluated (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV positive | HIV negative | p value | HIV positive | HIV negative | p value | |

| Bile acids (μmol/L) | ||||||

| Entry1 | 4.96 (3.63, 6.76) | 4.75 (4.05, 5.56) | 0.798 | 7/20 (35.00) | 10/23 (43.48) | 0.571 |

| Last pregnancy visit2 | 4.04 (3.43, 4.76) | 4.45 (3.49, 5.68) | 0.494 | 2/21 (9.52) | 2/21 (9.52) | 1.0 |

| Post-partum3 | 4.73 (3.40, 6.59) | 5.16 (4.18, 6.38) | 0.639 | 6/14 (42.86) | 11/18 (61.11) | 0.305 |

| Aspartate transaminase (AST; U/L) | ||||||

| Entry | 16.2 (12.85, 20.42) | 22.5 (20.07, 25.13) | 0.013 | 2/20 (10.00) | 6/22 (27.27) | 0.155 |

| Last pregnancy visit | 20.4 (15.93, 26.18) | 24.0 (22.38, 25.76) | 0.202 | 3/19 (15.79) | 1/21 (4.76) | 0.246 |

| Post-partum | 23.7 (17.26, 32.47) | 27.7 (23.11, 33.26) | 0.362 | 2/14 (14.29) | 4/17 (23.53) | 0.517 |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT; U/L) | ||||||

| Entry | 19.5 (14.57, 26.07) | 19.6 (16.27, 23.65) | 0.968 | 4/20 (20.00) | 2/22 (9.09) | 0.313 |

| Last pregnancy visit | 22.0 (16.38, 29.50) | 18.0 (15.40, 20.95) | 0.213 | 4/19 (21.05) | 1/21 (4.76) | 0.12 |

| Post-partum | 30.9 (22.81, 41.75) | 29.5 (21.83, 39.81) | 0.82 | 4/14 (28.57) | 4/17 (23.53) | 0.75 |

| γ-glutamil transpeptidase (GGT; U/L) | ||||||

| Entry | 15.7 (8.03, 30.73) | 11.0 (9.66, 12.47) | 0.284 | 4/19 (21.05) | 0/22 (0.00) | 0.023 |

| Last pregnancy visit | 17.0 (7.80, 36.85) | 10.8 (8.66, 13.55) | 0.255 | 6/17 (35.29) | 1/20 (5.00) | 0.019 |

| Post-partum | 23.3 (13.67, 39.77) | 13.2 (10.99, 15.79) | 0.044 | 1/11 (9.09%) | 0/17 (0.00) | 0.206 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | ||||||

| Entry | 0.3 (0.24, 0.55) | 0.59 (0.48, 0.72) | 0.041 | 3/20 (15.00) | 16/22 (72.73) | <0.001 |

| Last pregnancy visit | 0.42 (0.29, 0.62) | 0.61 (0.51, 0.73) | 0.077 | 2/19 (10.53) | 7/21 (33.33) | 0.085 |

| Post-partum | 0.56 (0.36, 0.88) | 0.71 (0.57, 0.89) | 0.321 | 1/13 (7.69) | 0/17 (0.00) | 0.245 |

Median (IQR) gestational age = 21.4 (19.5–24.5) weeks

Median (IQR) gestational age = 36.0 (33.0 – 37.0) weeks

Median (IQR) time after delivery = 7.4 (5.6–12.1) weeks

The proportions of HIV-infected and uninfected participants with elevated AST for gestational age did not differ significantly. AST concentrations were significantly lower at entry in HIV-infected compared with uninfected women (p=0.01), but concentrations were similar at subsequent visits. ALT levels were similar and the proportions of subjects with elevated levels for the gestational age were also similar in the 2 groups both in pregnancy and post-partum. GGT elevations were present in a higher proportion of HIV-infected compared with uninfected women, but all concentrations were < 3-fold of the upper normal level the test. Total bilirubin levels were high in 1 to 3 HIV-infected and 0 to 16 uninfected pregnant women across all time points, with concentrations < 3-fold of the upper normal level the test.

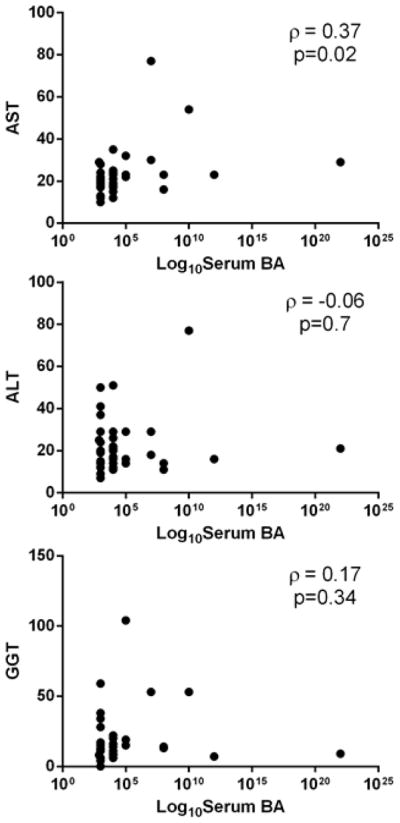

There was a weak, but significant correlation of bile acid with AST concentrations (ρ=0.37, p=0.02), but not with other LFTs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation analyses of maternal serum bile acid and liver enzyme levels during late pregnancy. Data were derived from 43 pregnant women. Panels A, B and C show correlation analyses of bile acid levels with AST, ALT and GGT levels, respectively. Spearman coefficients of correlation and p values are shown on each graph.

Characteristics of the neonates and their bile acid levels

There were 47 newborns, including 45 singletons and 1 pair of twins, after exclusion of pregnancies complicated by HCV co-infection. Seven of 22 HIV-exposed infants with known gestational age at birth (31.8%) were born before 37 weeks gestation compared with 2 out of 23 unexposed (8.7%, p=0.05; Table 3). The birth weight was lower in HIV-exposed compared with unexposed infants, but Apgar scores and bile acid levels were similar in HIV-exposed and unexposed infants.

Table 3.

Infant characteristics at birth.

| HIV exposed | HIV unexposed | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean weeks gestation at birth (95% CI) | 38 (36.9, 39.1) | 39.1 (38.3, 40) | 0.099 |

| Number born at <37 weeks gestation (percent) | 7/22 (31.8) | 2/23 (8.7) | 0.053 |

| Mean birth grams (95% CI) | 2761 (2534, 2988) | 3302 (3032, 3572) | 0.003 |

| Weight for gestational age | |||

| Number large for gestational age (%) | 0/21 (0) | 5/22 (22.7) | 0.02 |

| Number appropriate for gestational age (%) | 21/21 (100) | 17/22 (77.3) | |

| Mean one-minute APGAR score (95% CI) | 7.39 (6.45, 8.33) | 7.59 (6.98, 8.2) | 0.706 |

| Mean five-minute APGAR score (95% CI) | 8.78 (8.51, 9.05) | 8.95 (8.79, 9.12) | 0.254 |

| Mean bile acids (μmol/mL; 95% CI) | 4.45 (3.62, 5.45) | 4.36 (3.30, 5.77) | 0.961 |

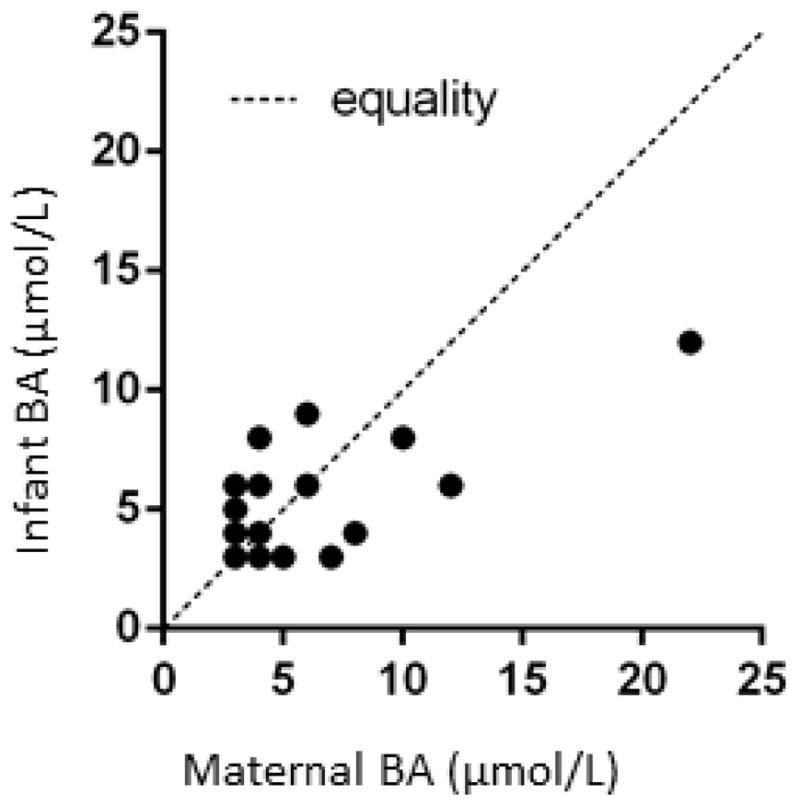

The analysis showed that late pregnancy maternal and infant cord blood bile acid concentrations had a correlation coefficient of 0.38 corresponding to a strong statistical trend (p=0.06; Figure 2). There were no significant correlations between maternal bile acid levels during late pregnancy and gestational age at delivery, infant weight or Apgar scores.

Figure 2.

Association of late pregnancy maternal and infant cord blood bile acid levels. Data were derived from 25 mother-infant pairs. The levels tended to correlate (rho=0.38, p=0.059).

Pregnancies complicated by HIV and HCV co-infection

Two HIV and HCV co-infected pregnant women were enrolled. One of the women had HCV viremia in addition to antibodies against HCV. Her 3rd trimester bile acid concentration was approximately 11-fold the upper normal limit at 106 μmol/L. She also had elevated AST, ALT and GGT at 3-, 1.5- and 2-fold, respectively, the upper normal limit but normal total bilirubin. This participant did not develop pruritus, but had premature labor at 28 weeks gestation, fetal distress and meconium-stained amniotic fluid at delivery, which are well-recognized complications of ICP. At the postpartum visit, the bile acid levels normalized at 8 μmol/L, but the hepatic enzymes remained elevated. The other HCV seropositive participant, who did not have detectable viremia, had an uneventful pregnancy and delivery and normal chemistry results at all visits.

Discussion

At the Children’s Immunodeficiency Mother-to-Child Prevention Program in Denver, Colorado, 4 out of 350 HIV-infected pregnant women were diagnosed with ICP over a period of 15 years, only 2 of whom had HCV co-infection (A. Weinberg, personal communication). One of these cases was complicated by fetal demise, which was avoided in the remaining 3 cases by early delivery with or without UDCA. This incidence of 1.14% was significantly higher compared with the overall incidence of 0.2% at our institution over a period of 5 years (26 cases of ICP per 13700 live births; J. Davies, personal communication) and prompted us to conduct this pilot study. However, our data showed that HIV infection and use of HAART during pregnancy were not associated with increased bile acid concentrations in the absence of HCV co-infection. The number of subjects enrolled in this study was too small to draw definitive conclusions on the incidence of ICP, but all the bile acid levels in pregnant women without HCV infection were <40 μmol/L, a threshold that has been previously shown to correlate with the development of ICP [22]. Therefore, our findings suggest that HIV-infected pregnant women on HAART may not be at increased risk of ICP in the absence of HCV co-infection. This is also in accordance with the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry data in which the incidence of ICP in HIV-infected pregnant women has been similar to the incidence in the general population.

Our data showed that GGT was more frequently abnormal in HIV-infected compared with uninfected pregnant women. Mildly elevated LFTs (<3-fold the upper normal level of the test) are common findings in HIV-infected individuals, including pregnant women, and may be caused by HIV-infection and/or drug-associated liver toxicity. However, mildly elevated occurred in a large proportion of HIV-uninfected pregnant women, too. The frequency of mildly abnormal results was partially driven by the low pregnancy-specific normal standard values reported by Abbassi-Ghavanati et al. [21]. Correlation analyses showed significant associations between bile acid levels and AST concentrations, which did not differ between HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women.

Very little is known about the effect of elevated serum bile acid levels in the fetus or infant other than the deleterious effect of highly increased serum bile acids on the overall outcome of pregnancy including increased incidence of spontaneous premature delivery, stained meconium, in-utero fetal distress and fetal demise. Fetal demise has been ascribed to vasoconstriction of the placental circulation [1]. We sought to determine if bile acid elevations below the threshold associated with ICP may be associated with placental deficiency reflected on infant gestational age and/or weight at birth and/or Apgar scores. Although none of the infant parameters measured in this study were associated with maternal bile acid levels in late pregnancy, the findings cannot be considered definitive due to the limited number of subjects with abnormal bile acid levels and the small elevations that were observed. Larger studies are warranted to further explore this association.

The HIV-infected pregnant woman with active HCV infection had high serum bile acids, in the range associated with ICP. Although she did not have pruritus, she had other complications consistent with ICP, including premature labor at 28 weeks gestation, fetal distress and meconium-stained amniotic fluid. This underscores the risk of ICP associated with active HCV infection. HCV co-infection occurs in 15 to 30% of HIV-infected individuals in the US [23]. HIV-infected pregnant women with active HCV infection may warrant serum bile acid level monitoring in the second half of pregnancy. The pregnancy outcome of women with bile acid concentrations ≥ 40 μmol/L, even in the absence of pruritus, may benefit from antepartum surveillance of the fetus beginning at 36 or 37 weeks gestation [22,24] or even as early as 26 to 27 weeks gestation in those women with known elevated levels or other risk factors for adverse outcome. In addition, new therapeutic interventions, such as dexamethasone, are being explored [25]. The results of a randomized trial of UCDA and/or induction of delivery at 37–38 weeks gestation may soon become available and may inform on the utility of these potential interventions [11].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant M01 RR000069 (AW) and NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000154. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. We thank Donna Roden for subject enrollment.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Davies MH, da Silva RC, Jones SR, Weaver JB, Elias E. Fetal mortality associated with cholestasis of pregnancy and the potential benefit of therapy with ursodeoxycholic acid. Gut. 1995;37:580–584. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.4.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pathak B, Sheibani L, Lee RH. Cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37:269–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie KK, Reznikov L, Simon FR, Fennessey PV, Reyes H, et al. Estrogens in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:372–376. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reyes H, Sjövall J. Bile acids and progesterone metabolites in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Ann Med. 2000;32:94–106. doi: 10.3109/07853890009011758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter J. Serum bile acids in normal pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:540–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb10367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker IA, Nelson-Piercy C, Williamson C. Role of bile acid measurement in pregnancy. Ann Clin Biochem. 2002;39:105–113. doi: 10.1258/0004563021901856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brites D, Rodrigues CM, van-Zeller H, Brito A, Silva R. Relevance of serum bile acid profile in the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in an high incidence area: Portugal. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;80:31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigues CM, Marín JJ, Brites D. Bile acid patterns in meconium are influenced by cholestasis of pregnancy and not altered by ursodeoxycholic acid treatment. Gut. 1999;45:446–452. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicastri PL, Diaferia A, Tartagni M, Loizzi P, Fanelli M. A randomised placebo-controlled trial of ursodeoxycholic acid and S-adenosylmethionine in the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1205–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zapata R, Sandoval L, Palma J, Hernández I, Ribalta J, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. A 12-year experience. Liver Int. 2005;25:548–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurung V, Williamson C, Chappell L, Chambers J, Briley A, et al. Pilot study for a trial of ursodeoxycholic acid and/or early delivery for obstetric cholestasis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roncaglia N, Arreghini A, Locatelli A, Bellini P, Andreotti C, et al. Obstetric cholestasis: outcome with active management. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;100:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(01)00463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistry HD, Broughton Pipkin F, Redman CW, Poston L. Selenium in reproductive health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pauli-Magnus C, Meier PJ, Stieger B. Genetic determinants of drug-induced cholestasis and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:147–159. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackillop L, Williamson C. Liver disease in pregnancy. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86:160–164. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.089631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paternoster DM, Fabris F, Palù G, Santarossa C, Bracciante R, et al. Intra-hepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in hepatitis C virus infection. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arribas JR, Ibáñez C, Ruiz-Antoran B, Peña JM, Esteban-Calvo C, et al. Acute hepatitis in HIV-infected patients during ritonavir treatment. AIDS. 1998;12:1722–1724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soriano V, Puoti M, Garcia-Gascó P, Rockstroh JK, Benhamou Y, et al. Antiretroviral drugs and liver injury. AIDS. 2008;22:1–13. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f0e2fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouyang DW, Shapiro DE, Lu M, Brogly SB, French AL, et al. Increased risk of hepatotoxicity in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving antiretroviral therapy independent of nevirapine exposure. AIDS. 2009;23:2425–2430. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e34b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinstock DM, Merrick S, Malak SA, Jacobs J, Sepkowitz KA. Hepatitis C in an urban population infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS. 1999;13:2593–2595. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912240-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbassi-Ghanavati M, Greer LG, Cunningham FG. Pregnancy and laboratory studies: a reference table for clinicians. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1326–1331. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2bde8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egan N, Bartels A, Khashan AS, Broadhurst DI, Joyce C, et al. Reference standard for serum bile acids in pregnancy. BJOG. 2012;119:493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C Virus prevalence among patients infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:831–837. doi: 10.1086/339042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williamson C, Hems LM, Goulis DG, Walker I, Chambers J, et al. Clinical outcome in a series of cases of obstetric cholestasis identified via a patient support group. BJOG. 2004;111:676–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diac M, Kenyon A, Nelson-Piercy C, Girling J, Cheng F, et al. Dexamethasone in the treatment of obstetric cholestasis: a case series. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26:110–114. doi: 10.1080/01443610500443246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]