Abstract

Background:

Periodontitis is a chronic, multifactorial, polymicrobial disease causing inflammation in the supporting structures of the teeth. There is a plethora of nonoral risk factors which can be quoted to aid in the development of chronic periodontitis. According to WHO, depression is a common mental disorder that presents with depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt, disturbed sleep or appetite, low energy and poor concentration. Depression is associated with negligent oral health care and another mechanism proposed disturbance in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis system and hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid system, which can affect the periodontal status by affecting the immune system.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to assess the association between periodontal clinical parameters and depression rating.

Materials and Methods:

The study design is a case–control study with 35 patients each in case and control group. The periodontal parameters taken for measurement were probing depth and clinical attachment loss. Depression was calculated using Beck's depression scale.

Statistical Analysis:

The statistical analysis was performed by means of SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA; version 17.0 under windows 2000). Student's t-test was used to determine the relationship between the clinical periodontal parameters and depression.

Results:

Self-reported scoring of depression by using Beck's depression inventory has shown that periodontal patients had a significantly higher total depression score than normal controls.

Conclusion:

This study reveals that there is a direct correlation between the severity of periodontal disease and the severity of depression in patients.

Keywords: Chronic periodontitis, depression, probing depth and clinical attachment loss

INTRODUCTION

Chronic periodontitis is a disease caused by multiple factors hence can be called multifactorial disease. Plaque is a biofilm, which harbors concrete periodontal pathogens, and it can be addressed as the primary causative of chronic periodontitis.[1] The development of periodontitis and the progression of the disease varies from individual to individual due to the nonoral risk factors that vigorously associate with the development of periodontitis. Such kenned risk factors include smoking, diabetes mellitus, genetics, stress, melancholy, and solicitousness.[2]

Depression is one of the most common psychiatric illness; considerable health problems can be caused by both major depression and sub threshold depressive symptoms.[3] The biological plausibility for an association between depression and periodontitis has been proposed by various studies. These studies have demonstrated that depression and stress could modify the immune response of an individual making him/her more prone to develop an insalubrious condition and may also cause an impact on periodontal health.[4] Few biological psychosocial hypotheses expounding the relationship between depression and periodontal health exist. Of the proposed mechanisms, that attempt to associate psychosocial factors to periodontitis the negligence of oral health care behavior is most important.[5] This hypothesis is predicated on the postulation that depressed patients ignore oral hygiene maintenance and professional regular dental care due to reduced motivation and interest. Depression is additionally associated with unhealthy habits such as smoking and alcohol dependence two factors that are also known to increase one's risk for chronic periodontitis.[6,7] Another potential mechanism, whereby depression may be an additional risk factor to the development and progression of disease, is through alterations in host immune response, making the individual more prone to develop an overall unhealthy condition and this may also impact periodontal health.[8]

The relationship between psychological factors and periodontitis warrants punctiliously structured studies because various studies have shown that psychological states can play a role in the course of chronic diseases. An understanding of this relationship is required for further planning in the aversion and treatment of periodontal disease. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between periodontal clinical parameters and depression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study is a case–control study and using convenience sampling, 35 patients of both sexes (22 men and 13 women) aged between 25 and 55 years diagnosed as suffering from periodontitis were enrolled in this study. Inclusion criteria were based on American Academy of Periodontology criteria. A control group of 35 patients (17 men and 18 women) aged between 25 and 55 years, not suffering from periodontitis were taken for comparison of results of periodontal and depression investigations.

The study protocol was approved by Institutional Ethical Committee and informed consent was obtained from the participants. Medical and dental histories were obtained from both cases and controls. Smokers (current and past) were excluded from the study to eliminate the effect of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics along with gender and age. Oral hygiene index (OHI) was measured for all cases and controls. OHI has two components - debris and calculus index, which is measured for 6 representative teeth (16, 11, 26, 36, 31 and 46) and the mean value was interpreted. Periodontal parameters studied included probing depth (PD), clinical attachment loss (CAL) measured at 6 sites per tooth, by using a William's periodontal probe by a single trained examiner to eliminate bias. Clinical evidence of loss of attachment was taken for the diagnosis of periodontitis. The patients of the control group were required to fulfill the following criteria: No clinical loss of attachment caused by periodontal disease and a maximum PD of 4 mm in the dentition.

The depression levels were assessed by Beck's depression inventory. It is a self-reported scale consisting of 21 statements including symptoms and attitude. Each of the 21 statements is scored from 0 to 3. The statements are related to sadness, pessimism, sensation of failure, lack of satisfaction, suicidal ideation, irritability and social retraction among others.[9] Beck's depression inventory was scored by adding the greatest value of each statement. In the present study cut-off score of 17 or greater identified the patient with depression symptoms. The scale was also validated in Brazil.[10]

Statistics

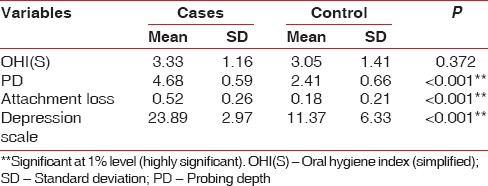

The statistical analysis was performed by means of SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA; version 17.0 under windows 2000). Student's t-test was used to determine the relationship between the clinical periodontal parameters and depression and the results were tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relationship between periodontal clinical parameters and depression

RESULTS

The periodontal variables were correlated with levels of depression based on Beck's depression inventory, the following results were obtained.

Periodontal variables

Mean CAL was 0.18 ± 0.21 for control group compared to 0.52 ± 0.26 for cases, which was statistically significant at P < 0.001 and mean PD was 2.41 ± 0.66 for control group compared to 4.68 ± 0.59 for cases, which were statistically significant at P < 0.001. The mean depression value 11.37 ± 6.33 for the controls compared to 23.89 ± 2.97 for cases, which was statistically significant at P < 0.001 [Table 1 the higher the self-rated Beck's depression scores more pronounced periodontal disease severity as assessed by PD, CAL].

DISCUSSION

Periodontitis is an infectious disease and the risk factors affecting the host can modify its onset and progression.[11] Depressive mood is considered as an important risk factor for the development, rigor and course of periodontitis. Anyhow a correlation between periodontitis and depression are largely inconclusive. Hence in the present study, we preferred to analyze the role of depression in the progression of periodontitis. Clinical investigations on the level of depression between periodontitis patients and controls showed that the patients had significantly higher scores in the self-rated depression scales.

Numerous screening tools have been specifically designed to identify depressive symptoms or possible presence of depression and self-reporting measures have been advocated as a simple, expeditious and inexpensive method to ameliorate detection. Studies have demonstrated the reliability of utilizing self-reporting depression/depressive symptoms for research purpose, hence the Beck's depression inventory, which is one of the most prevalent depression/depressive symptoms screening measures was used in the present study.[12]

Partial correlation analysis (controlling for the effects of age, smoking and gender) reveal significant positive correlation between the severity of periodontal disease (PD, CAL) and depression determined by means of Beck's depression inventory.

Our findings are in agreement with the majority of the literature. Studies by Moss et al., 1996. reveals that depression was associated with a more rigorous course of periodontitis.[13] Significant correlation between periodontal status and psychopathology of psychiatric patients has been described by Baker et al. Belting and Gupta, 1961 reported a deteriorated periodontal status in psychiatric patients when compared with controls, the results of which are similar to the above study.[14]

The study by Davis and Jenkins in 1961 revealed the association between periodontal disease severity and increased anxiety, which is in agreement with our present study. This study has hypothesized that anxiety increases blood levels of adrenocorticotropic hormones (ACTHs) such as cortisol, which has a negative effect on periodontal immune mechanism.

Neuroendocrinal studies mainly suggest that in depression there is a disturbance in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis system and hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid system.[15] Increased release of corticotropin releasing hormone leading to hypersecretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol is caused by an alteration in the limbic system.

The negative effects of cortisol on immune defense mechanism also negatively influence the initiation and course of periodontitis.[11] The results of the present study clearly demonstrate the relationship between depression and periodontitis. However, apart from age, gender and smoking the other demographic factors and socioeconomic characteristics such as education, lifestyle, nutritional status were not considered, which is one of the limitations of our study. Longitudinal studies with increased sample size emphasizing on clinical, neurophysiological, neuroendocrinological and psychopharmacological investigations would give conclusive evidence on the role of depression in progression of periodontitis.

CONCLUSION

The depression scale may be a valuable tool in a modern periodontal practice that emphasizes individual diagnosis, treatment planning, and maintenance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Genco RJ. Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1041–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johannsen A, Rydmark I, Söder B, Asberg M. Gingival inflammation, increased periodontal pocket depth and elevated interleukin-6 in gingival crevicular fluid of depressed women on long-term sick leave. J Periodontal Res. 2007;42:546–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wulsin LR. Does depression kill? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1731–2. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biondi M, Zannino LG. Psychological stress, neuroimmunomodulation, and susceptibility to infectious diseases in animals and man: A review. Psychother Psychosom. 1997;66:3–26. doi: 10.1159/000289101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurer JR, Watts TL, Weinman J, Gower DB. Psychological mood of regular dental attenders in relation to oral hygiene behaviour and gingival health. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:52–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence and major depression. New evidence from a prospective investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:31–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marmorstein NR. Longitudinal associations between alcohol problems and depressive symptoms: Early adolescence through early adulthood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00810.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin M, Patterson T, Smith TL, Caldwell C, Brown SA, Gillin JC, et al. Reduction of immune function in life stress and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;27:22–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90016-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorenstein C, Andrade L. Validation of a Portuguese version of the beck depression inventory and the state-trait anxiety inventory in Brazilian subjects. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1996;29:453–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genco RJ, Ho AW, Kopman J, Grossi SG, Dunford RG, Tedesco LA. Models to evaluate the role of stress in periodontal disease. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:288–302. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saletu A, Pirker-Frühauf H, Saletu F, Linzmayer L, Anderer P, Matejka M. Controlled clinical and psychometric studies on the relation between periodontitis and depressive mood. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:1219–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moss ME, Beck JD, Kaplan BH, Offenbacher S, Weintraub JA, Koch GG, et al. Exploratory case-control analysis of psychosocial factors and adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1060–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belting CM, Gupta OP. The influence of psychiatric disturbances on the severity of periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1961;32:219–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiger AE. The interaction of sleep and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical system. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:125–38. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]