Abstract

Background:

The habit of tobacco consumption has plagued all nations from time immemorial. While tobacco use is decreasing in many developed countries, it is increasing in developing countries like India. Health care professionals have a key role to play to motivate and advise tobacco users to quit.

Aim:

The aim was to assess the attitudes and practice of dental professionals in Mumbai and Navi Mumbai toward tobacco cessation and the potential barriers faced.

Materials and Methods:

Questionnaire-based survey was conducted with 500 dental surgeons in Mumbai and Navi Mumbai. The questionnaire contained close-ended questions and assessed the smoking status of the professional, whether they impart tobacco cessation advice to their patients, whether the professional is trained for basic intervention, whether they would be eager to undergo training and also the potential barriers encountered by the professional.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The SPSS version 17 was used. Frequencies and percentages were used to determine distributions of the responses for each of the variables. Chi-square test was used for analysis.

Results:

It was observed that the majority of dental clinicians do not use tobacco and although 93% believed that it is the role of the dental professional to offer advice, 21% do not. Potential barriers reported were: Little chance of success, lack of training, lack of time, lack of remuneration, and the possibility of losing patients.

Conclusions:

Dental professionals must expand their horizon and armamentarium to tobacco intervention strategies inclusive of their regular preventive and therapeutic treatment modalities. Furthermore, the dental institutions (schools) should include tobacco intervention in the curriculum, but it should not be just theoretical knowledge rather it must have a practical component.

Keywords: Attitudes, barriers, dental professionals, tobacco cessation

INTRODUCTION

The habit of tobacco consumption has plagued all nations from time immemorial. While tobacco use is decreasing in many developed countries, it is increasing in developing countries like India. The latest nationally representative Global Adult Tobacco Survey, estimated that India had 275 million current tobacco users in the year 2009–2010 (over 35% of adults): Majority of them used smokeless tobacco (164 million) and 42 million used both forms of tobacco. An estimated 1 million people die every year due to tobacco-related diseases in India.[1] In order to reduce the impact of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality, we need a combination of strategies aimed at avoiding the initiation of tobacco by the nonusers and cessation of tobacco use among current users. According to Shafey et al., if the current use of tobacco among adults is reduced to half, 180 million deaths that would happen due to tobacco by the year 2020, could be avoided.[2] In this regard, Indian Dental Association has initiated the tobacco intervention initiative (TII) which is aimed to eradicate tobacco addiction and strive for a “tobacco free India” by 2020.

Health care professionals have a key role to play by working through the health care system to motivate and advise users to quit. It is said that it is the obligation of the dental surgeon to curb the menace of tobacco. TII has introduced programs where dental surgeons are motivated and trained for the same.

Significant barriers to anti-tobacco counseling by health professionals have been found to be as a result of self-use of tobacco, lack of training in counseling patients about quitting tobacco use, etc., But one does not know how far one has progressed in involving dental surgeons in the tobacco eradication programs.

We, therefore, attempted to carry out a survey to assess the attitudes of dental professionals in Mumbai and Navi Mumbai toward tobacco cessation and the potential barriers faced.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was carried out by the Department of Periodontology, Terna Dental College, Navi Mumbai, among dental professionals with a minimum qualification of Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) which included dentists practicing in Navi Mumbai and Mumbai, India, during the period from October 2013 to January 2014. The study was carried out among 500 practicing dentists using convenience sampling.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee before the start of the study. All participants were assured of confidentiality before the start of the study. All the participants were given a self-administered, close-ended questionnaire by the investigator to assess the attitude toward tobacco cessation and barriers perceived by them to tobacco cessation advice.

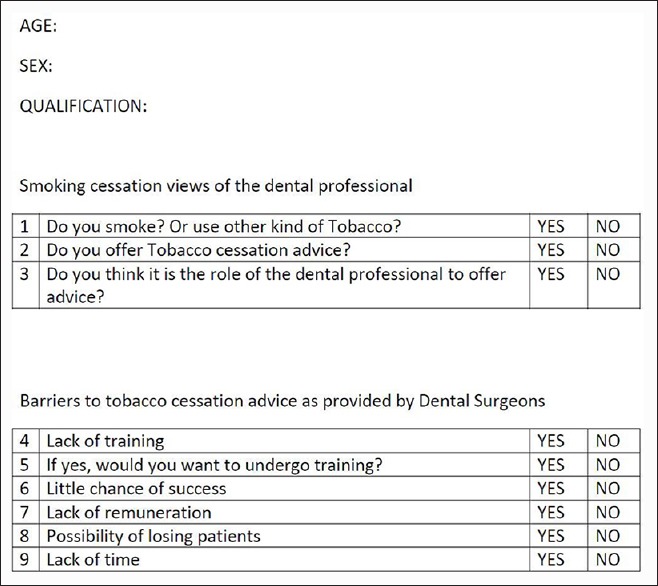

The questionnaire was prepared by the investigators [Figure 1]. The response sheets were personally collected by the investigator.

Figure 1.

Sample questionnaire

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17. 0. Chicago: SPSS Inc Frequencies and percentages were used to determine distributions of the responses for each of the variables. Chi-square test was used for analysis.

RESULTS

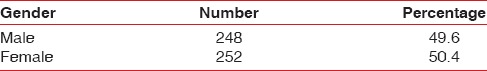

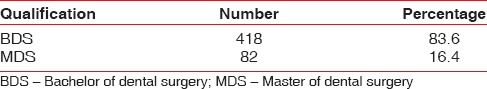

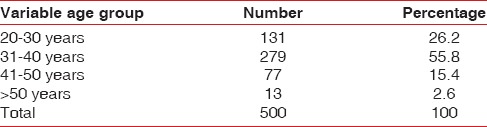

A total of 500 Dental Professionals of Navi Mumbai and Mumbai, India, participated in the study with almost equal numbers of males and females [Table 1]. Of these, 418 (83.6%) were BDS and 82 (16.4%) were Master of Dental Surgery (MDS) [Table 2]. The mean age for participants was 34 years. In the present survey, most of the respondents (58.8%) belong to the age group between 31 and 40 years whereas least (2.6%) number of respondents was >50 years of age [Table 3].

Table 1.

Gender distribution of the population

Table 2.

Qualification distribution of the population

Table 3.

Age distribution of the population

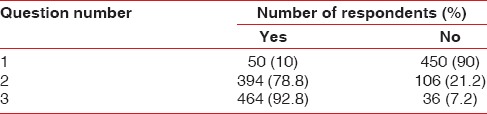

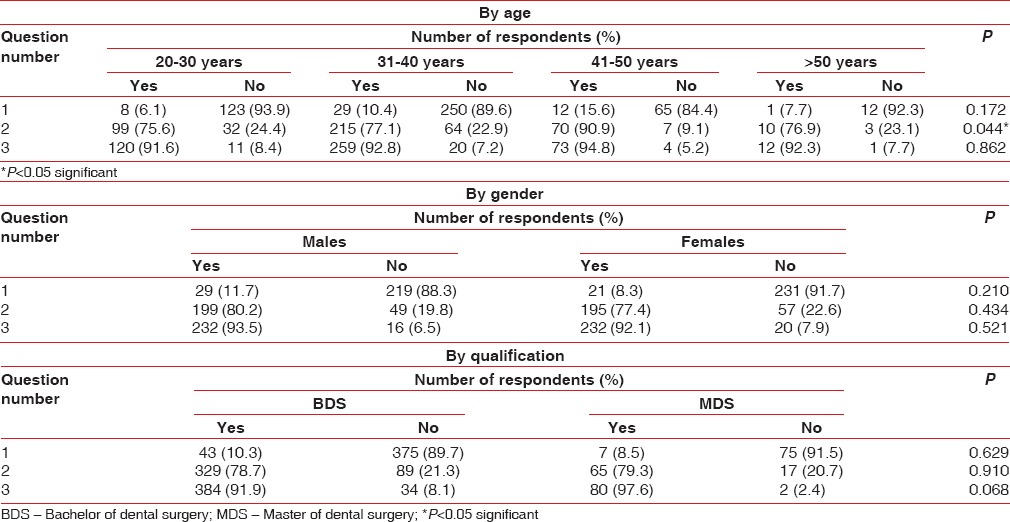

When asked whether they smoke, only 10% of the professionals responded that they did while majority (90%) of them did not smoke or use any other form of tobacco. 92.8% professionals thought that they had a role to play in providing tobacco cessation advice, but only 78.8% admitted to being actively involved [Table 4]. When views of dental professionals were analyzed with respect to age, it was seen that as the age advances, more likely they were to advice tobacco cessation. In the present study, senior dentists (41–50 years) were more to advice tobacco cessation than others. No statistically significant difference was observed for barriers to tobacco cessation advice as perceived by dental professionals with respect to age. Representation of views of dental professionals toward tobacco cessation by age, gender, and qualification is given in Table 5.

Table 4.

Attitude of dental professionals toward tobacco use

Table 5.

Representation of smoking cessation views of dental professional

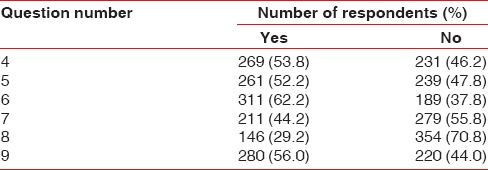

Little chance of success was regarded as a major potential barrier to tobacco cessation advice as considered by 62.2% respondents. Lack of time (56%) and remuneration (44.2%) were also regarded as significant barriers. Only 29.2% professionals thought the possibility of losing patients as a barrier to tobacco cessation [Table 6].

Table 6.

Barriers to tobacco cessation advice by dental professionals

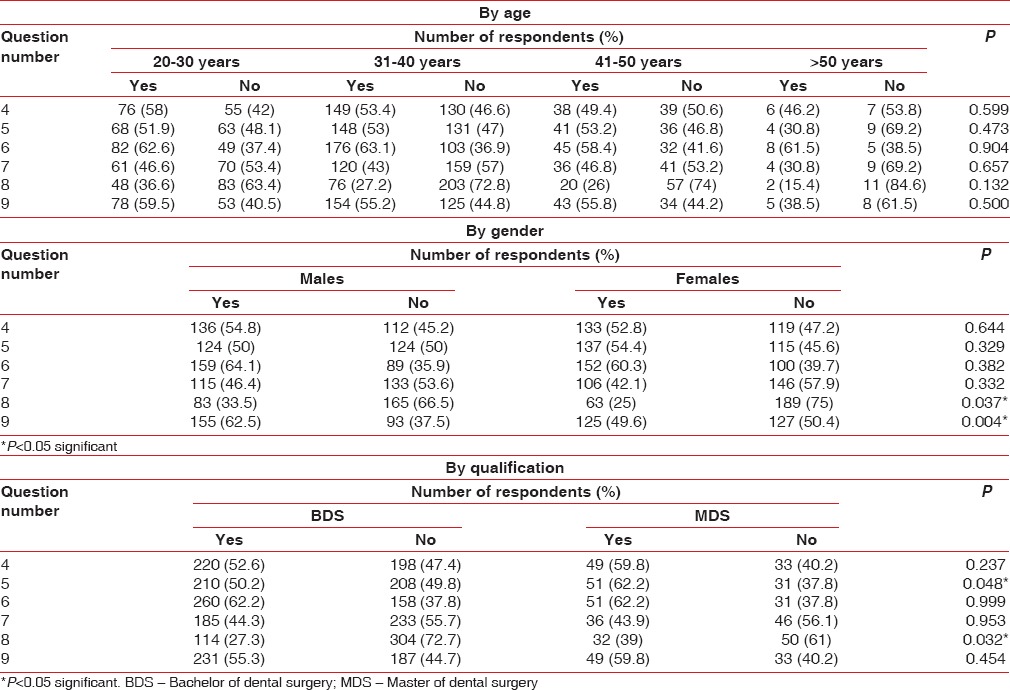

Representation of barriers to tobacco cessation advice as perceived by dental professionals by age, gender, and qualification is given in Table 7.

Table 7.

Representation of barriers to tobacco cessation advice as perceived by dental professionals

In our study, 53.8% respondents felt that the lack of training prevented them from giving tobacco cessation advice and those who thought that almost all (97%) of them were ready to undergo training. In addition, out of total MDS dental professionals 62.2% were more likely to undergo training, whereas only 50.2% BDS professionals agreed to the same, and this was found to be statistically significant.

When barriers to tobacco cessation advice were evaluated with respect to gender significant number of male respondents believed lack of time (62.5%) and possibility of losing patients (33.5%) as barriers, compared to female respondents. When same was evaluated with respect to qualification 39% MDS respondents thought that there is a possibility of losing patient. No significant difference observed with respect to views of dental professionals and other major barriers such as little chance of success, lack of training, and remuneration in regards to gender and qualification.

DISCUSSION

Since providing tobacco cessation advice is an integral part of dental care, this questionnaire-based survey aimed to ascertain the attitude of dental professionals toward tobacco cessation in general dental practice. The dental profession is in an excellent position to provide tobacco cessation counseling, and there is some evidence that interventions in the dental setting are successful.[3] The result of the survey has offered some encouragement regarding views of dentists’ current activities and the opportunities for future involvement in tobacco cessation advice.

In the present study, maximum number of dental professionals did not prefer to use tobacco. Only 10% of the dental professionals were found to be smokers and using any other form of tobacco. With these findings, the concept of health professionals being role models has got a strong support. It seems logical to state that if health professionals are role models and when health professionals are not smoking, then the effectiveness of counseling to patients will be increased.[4]

Dental professionals are well-placed to recognize tobacco users and can also identify the impact of its use in the mouth. Furthermore, dental treatment often requires multiple visits. Hence, it provides a system for initiation, reinforcement, and support of tobacco cessation activities. Dental professionals have the advantage to correlate cessation advice and subsequent follow-up visits with the obvious visible changes in the oral status.

A study by Stacey et al. has shown that dentists who smoke; are less likely to offer smoking cessation advice than those who do not smoke[5] In a study in UK by Macgregor where smoking cessation advice was given in addition to treatment compared with a treatment only, 13% of intervention group had quit smoking as compared to 5% of control group.[6]

The majority of studies conducted have shown that dental health care workers believe that it is appropriate, or it is the dentists’ duty to become involved in smoking cessation activities.[7,8,9] In our study, most of the respondents believed that it is primarily their role to advice on tobacco cessation to their patients in contrast to data from European studies which indicates that only 71% of health professionals view themselves as role models for tobacco cessation.[4] In spite of this belief, not all of the dentists surveyed in our study were currently offering advice on tobacco cessation in their clinical practice. This finding is in accordance with the study carried out in UK where only 63% promoted smoking cessation advice among 82% of professionals who thought that they have a major role.[5] In the present study, it was observed that senior dental professionals were more likely to advice tobacco cessation than others. This view of senior professionals could be attributed to their experience in treating patients.

The difference between the perceived role of the dental professionals and their actual involvement toward tobacco cessation advice suggests that there are certain barriers to offering tobacco cessation advice. Barriers to providing tobacco cessation advice are apparent in both the medical and dental professions. Past studies have reported that the most common barriers seem to be a lack of time, lack of training, financial constraints, and the risk of alienating patients.[10,11,12,13]

Majority of respondents in our survey suggested little chance of success as a barrier, although in the UK dentist survey this was cited as least important as only 25% of them felt so.[14] This could be attributed to the lack of motivation and awareness among Indian population toward oral hygiene. The results of the EU survey found the lack of time and lack of reimbursement mechanisms as barriers.[7] The results of UK dentists study indicated that the above two barriers were more regularly a problem for general dental practitioners than salaried dentists.[14] Other studies that have surveyed general dental practitioners indicate that lack of time often seems to be the most important barrier.[10,14] The present study also supported the lack of time and remuneration being the next important barriers toward cessation as cited by 56% and 44.2% professionals, respectively, and all of them were practicing dentists. Lack of funding may result in less time spent advising patients. In the present study, significant number of male respondents felt lack of time as a barrier when compared to female respondents.

Lack of training was cited as a next important barrier to giving tobacco cessation advice. More than half of the professionals thought lack of training as a barrier and the majority of them were willing to receive training. Significantly higher percentage of MDS professionals was ready to undergo training than BDS professionals. In 2006, the Commonwealth Dental Association produced a consensus on tobacco cessation. They agreed that training in tobacco control should be provided to dental undergraduates to enable them to inform patients of the risks of tobacco use and support their patients in quitting smoking.[15]

The number of dental health workers who felt the possibility of losing patient was a barrier for tobacco cessation advice, in the present study was relatively low. In addition, it was seen that significant number of dental professionals those who thought the possibility of losing patients as a barrier were males and MDS professionals.

CONCLUSION

Dental professionals have been identified as having an important role to play in supporting tobacco users who desire to quit. Evidence-based guidelines provide a clear way forward for all health professionals to become engaged in this important area of prevention. A reduction in tobacco use would improve both general and oral health, and would help to reduce widening inequalities across the population. A range of barriers have been reported by dentists to explain the low level of routine involvement in smoking cessation activities within dental practices despite positive attitudes. The main barriers reported by dental professional in our survey include little chance of success, lack of time and remuneration, lack of training. Variety of factors should be considered to overcome these barriers. Dental professionals must expand their horizon and armamentarium to include tobacco intervention strategies in addition to their regular preventive and therapeutic treatment modalities. Furthermore, dental institutions should include tobacco intervention in the curriculum, but it should not be just theoretical knowledge, rather it must have a practical component so that the upcoming bunch of professionals have the requisite and desired competency to fight one of the preventable causes of death. Students and interns should also be inspired and motivated to carry out tobacco awareness and cessation programs. It is also recommended to train the dental professionals at the primary and community health care levels in the treatment of tobacco dependence, as most people in India cannot afford to go to specialist tobacco cessation counseling centers nor can the government afford to run them on large scale.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2010. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) Mumbai. Global Adult Tobacco Survey India (GATS India), 2009-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shafey O, Eriksen M, Ross H, Mackay J. 3rd ed. Atlanta, Georgia, USA: American Cancer Society; 2009. The Tobacco Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell HS, Sletten M, Petty T. Patient perceptions of tobacco cessation services in dental offices. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:219–26. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singla A, Patthi B, Singh K, Jain S, Vashishtha V, Kundu H, et al. Tobacco Cessation counselling practices and attitude among the dentist and the dental auxiliaries of urban and rural areas of Modinagar, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZC15–8. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9250.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stacey F, Heasman PA, Heasman L, Hepburn S, McCracken GI, Preshaw PM. Smoking cessation as a dental intervention – Views of the profession. Br Dent J. 2006;201:109–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macgregor ID. Efficacy of dental health advice as an aid to reducing cigarette smoking. Br Dent J. 1996;180:292–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allard RH. Tobacco and oral health: Attitudes and opinions of European dentists; a report of the EU working group on tobacco and oral health. Int Dent J. 2000;50:99–102. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John JH, Thomas D, Richards D. Smoking cessation interventions in the Oxford region: Changes in dentists’ attitudes and reported practices 1996-2001. Br Dent J. 2003;195:270–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyne AH, Chohan AN, Al-Moneef MM, Al-Saad AS. Attitudes of general dentists about smoking cessation and prevention in child and adolescent patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006;7:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chestnutt IG, Binnie VI. Smoking cessation counselling – A role for the dental profession? Br Dent J. 1995;179:411–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clover K, Hazell T, Stanbridge V, Sanson-Fisher R. Dentists’ attitudes and practice regarding smoking. Aust Dent J. 1999;44:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1999.tb00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert D, Ward A, Ahluwalia K, Sadowsky D. Addressing tobacco in managed care: A survey of dentists’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:997–1001. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watt RG, McGlone P, Dykes J, Smith M. Barriers limiting dentists’ active involvement in smoking cessation. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson NW, Lowe JC, Warnakulasuriya KA. Tobacco cessation activities of UK dentists in primary care: Signs of improvement. Br Dent J. 2006;200:85–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Commonwealth Chewing and Smokeless Tobacco Cessation Statement. Commonwealth Dental Association Bulletin. 2006 Jun 13; [Google Scholar]