Abstract

Buccal exostosis is benign, broad-based surface masses of the outer or facial aspect of the maxilla and less commonly, the mandible. They begin to develop in early adulthood and may very slowly enlarge over the years. A 24-year-old female presented with gingival enlargement on the buccal aspect of both the quadrants of the maxillary arch. The overgrowth was a cosmetic problem for the patient. The etiology of the overgrowth remains unclear though the provisional diagnosis indicates toward a bony enlargement, which was confirmed with the help of transgingival probing. The bony enlargement was treated with resective osseous surgery. The following paper presents a rare case of the bilateral maxillary buccal exostosis and its successful management.

Keywords: Exostosis, resective osseous surgery, vertical grooving

INTRODUCTION

Enlargement of the bone subjacent to the gingival area occurs in tori, exostosis, fibrous dysplasia, cherubism, central giant cell granuloma, ameloblastoma, osteoma, and osteosarcoma. The gingival tissue can appear normal or may have unrelated inflammatory changes.[1]

Exostosis is bony hamartomas, which are asymptomatic, benign, exophytic nodular outgrowths of dense cortical bone that are relatively avascular.[2] They are mainly of two types: Buccal and palatal exostosis. These benign growths affect both the jaws. Maxilla is shown to exhibit the highest prevalence rate of 5.1:1 in comparison to mandible with a male population afflicted more than females 1.66:1, in all intraoral locations.[3]

The etiology of tori has been investigated by several authors; however, no consensus has been reached. Some of the postulated causes include genetic factors,[4,5,6,7] environmental factors,[8,9,10] masticatory hyperfunction,[10,11,12,13,14] and continued growth.[15] Gorsky et al. summarised that the etiology of these common osseous outgrowths is probably multifactorial, including environmental factors acting in a complicated and unclear interplay with genetic factors.[16]

With the growing emphasis on cosmetic dentistry and esthetics especially among the youngsters, surgical removal is routinely warranted for such lesions. The case report presented below illustrates the bilateral maxillary buccal exostosis and its successful management.

CASE REPORT

A 24-year-old female patient was reported to the Department of Periodontology and Oral Implantology, Maharishi Markandeshwar College of Dental Sciences and Research, Mullana with the complaint of swelling in right and left upper buccal region since 2 years [Figure 1]. The patient's medical and dental history was taken, which stated that the enlargement was familial in nature. She was not taking any medications, and she had no known drug allergies. There was no history of alcohol or tobacco use.

Figure 1.

Preoperative view showing enlargement at maxillary left buccal region

The overgrowth was a cosmetic problem for the patient. Transgingival probing revealed that the patient had thin gingival biotype, with underlying bony exostosis on the buccal aspect of both the quadrants of the maxillary arch. There was mild inflammation in the right side of the maxillary arch, and the probing depth were in the range of 2–3 mm. It was covered with thin mucosal tissue and did not interfere with speech, chewing, or other oral functions.

TREATMENT

The patient's treatment consisted of patient education, oral hygiene instructions, mechanical debridement and periodontal resective osseous surgery. She was placed on 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate twice daily mouth rinse, after scaling and root planning prior to surgery to reduce bacterial plaque and gingival inflammation. At the nonsurgical re-evaluation, there was no improvement in gingival enlargement, but the gingival tissues appeared healthier. Two weeks elapsed between the nonsurgical and surgical phases. Intraoral periapical X-ray [Figure 2] and routine blood and urine investigations were found to be noncontributory. After explaining the patient the potential risks and benefits of surgery, an informed consent was obtained.

Figure 2.

Preoperative intraoral periapical of maxillary left buccal region

After giving appropriate local anesthesia, a full thickness mucoperiosteal flap was reflected to gain complete access to the exostosis by giving horizontal crevicular and vertical incisions. Following exposure of the lesion, a periosteal elevator was placed at the apical end to prevent inadvertent injury during excision. Resective osseous surgery was carried out in the following four steps: Vertical grooving/festooning was done to reduce the thickness of the alveolar housing and to provide prominence to the radicular aspects of the teeth, with sharp carbide surgical bur at approx. 7000 rpm speed handpiece. The greatest mesiodistal width of teeth guided the vertical cuts to a depth of approximately 1–1.5 mm in the cortical bone [Figure 3]. Cooling with a copious spray of sterile saline was done. Radicular blending was done to gradualize the bone over the entire radicular surface. Flattening of interproximal bone was done since the interproximal bone levels varied horizontally. There small amount of supporting the bone was removed with the help of the chisel. Finally, the marginal bone was gradualized to provide a sound, regular base for gingival tissue to follow. The bone was removed with a chisel. Saline irrigation should also be carried out during chiseling since this generates heat. After removal of the osseous tissue, the flaps were positioned on a trial basis, and surgical site was palpated to determine the need for further recontouring. On obtaining the desired result, the flap was sutured with 3–0 silk.

Figure 3.

Vertical grooving at left maxillary buccal region

Routine postoperative instructions were given. The medications prescribed were, systemic antibiotic 500 mg amoxicillin and analgesic 400 mg ibuprofen every 8 h for 3 days. Patient was recalled after 1-week for suture removal and after 1, 3 and 6 months for further postoperative follow-up [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 4.

Six months postoperative view showing absence of enlargement at maxillary left buccal region

Figure 5.

Six months postoperative intraoral periapical of maxillary left buccal region

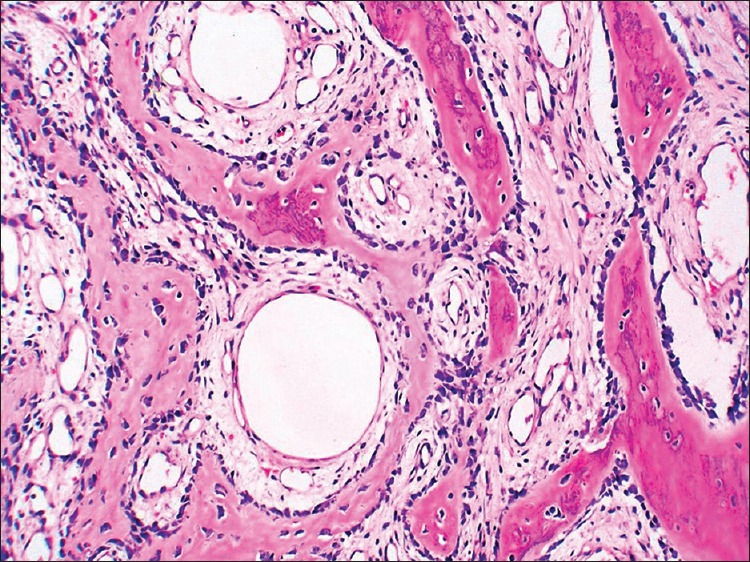

Chiseled marginal bone was sent for histopathologically examination and found that material was indeed just native bone that is, exostosis [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

H and E stained section of the specimen

DISCUSSION

In the present case report, based on patient's dental and medical history, it was difficult to ascertain a direct cause and effect. The patient was not on any medications. Disease was not familial in nature as the patient gave no history of such gingival overgrowth in her family.

False enlargements are not true enlargements of the gingival tissues but may appear as such as a result of the increase in size of the underlying osseous or dental tissues. The gingiva usually presents with no abnormal clinical features except the massive increase in size of the area. Buccal exostosis is benign outgrowths, which occur on the outer or facial aspect of the maxilla and less commonly, the mandible.[17] They are usually painless and self-limiting, but occasionally may become larger in size. These lesions are found in about 3% of adults and are more common in males than in females. The functional influences may contribute to the development of exostosis. Therefore, the altered function in an individual may lead to exostosis development in genetically predisposed populations.[16]

Usually the bicuspid and molar areas are the affected sites yet occasionally they may occur in other parts of the jaw, either as a smooth bulging of the bone surface continuous with the adjacent area or as discrete, multilocular spherical projections with a broad base that forms a nodular cluster.[18,19]

A differential diagnosis of Fibrous dysplasia and Gardner syndrome was made. Due to the lack of multiple polyposis of the large intestine; osteomas of the bones; multiple epidermoid or sebaceous cyst of the skin; particularly on the scalp and back; desmoid tumors; impacted supernumerary and permanent teeth in the present case Gardner syndrome was excluded.[20]

Clinical findings of nodular protuberances on the buccal surface of the maxilla bilaterally below the muccobuccal fold in the molar region over which the mucosa appeared blanced in the present case ruled out fibrous dyslasia. As, fibrous dysplasia usually presents as painless swelling or bulging of the jaw with malaligned teeth.[21]

In the present case, nonsurgical periodontal therapy alone did not reduce the gingival enlargement because it was bony enlargement, thus necessitating surgical intervention. Vertical grooving/festooning was the first step of the resective osseous surgery designed to reduce the thickness of the alveolar housing and to provide continuity from interproximal surface onto the radicular surface. Cooling with a copious spray of sterile saline is necessary so that the temperature of the bone is not raised beyond 47°C. Radicular blending is the extension of vertical grooving which gradualize the bone over the entire radicular surface to produce smooth and blended surface for good flap adaptation. It is indicated where thick ledges of bone present on the radicular surface, whereas it is contraindicated where thin, fenestrated radicular bone is present. Flattening of interproximal bone was done where interproximal bone levels varied horizontally. Gradualizing marginal bone was the minimal bone removal to provide a sound, regular base for gingival tissue to follow. Saline irrigation should also be carried out during chiseling, since this generates heat.[22]

CONCLUSION

Successful restitution of the physiological bony contour without any untoward complications was accomplished thus, affording as a viable therapeutic option whenever suitable indicated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank Dr. Manish Bathla, Associate Professor, MMISMSR, Mullana for preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carranza FA, Hogan EL. Gingival enlargement. In: Newman MG, Takei H, Carranza FA, Carranza F, editors. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 9th ed. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2003. pp. 279–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pynn BR, Kurys-Kos NS, Walker DA, Mayhall JT. Tori mandibularis: A case report and review of the literature. J Can Dent Assoc. 1995;61:1057–8. 63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jainkittivong A, Langlais RP. Buccal and palatal exostoses: Prevalence and concurrence with tori. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:48–53. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.105905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki M, Sakai T. A familial study of torus palatinus and torus mandibularis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1960;18:263–72. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichart PA, Neuhaus F, Sookasem M. Prevalence of torus palatinus and torus mandibularis in Germans and Thai. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1988;16:61–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1988.tb00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggen S. Torus mandibularis: An estimation of the degree of genetic determination. Acta Odontol Scand. 1989;47:409–15. doi: 10.3109/00016358909004810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorsky M, Bukai A, Shohat M. Genetic influence on the prevalence of torus palatinus. Am J Med Genet. 1998;75:138–40. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980113)75:2<138::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King DR, Moore GE. An analysis of torus palatinus in a transatlantic study. J Oral Med. 1976;31:44–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eggen S, Natvig B. Variation in torus mandibularis prevalence in Norway. A statistical analysis using logistic regression. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:32–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haugen LK. Palatine and mandibular tori. A morphologic study in the current Norwegian population. Acta Odontol Scand. 1992;50:65–77. doi: 10.3109/00016359209012748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews GP. Mandibular and palatine tori and their etiology. J Dent Res. 1933;13:245. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson OM. Tori and masticatory stress. J Prosthet Dent. 1959;9:975–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eggen S, Natvig B. Relationship between torus mandibularis and number of present teeth. Scand J Dent Res. 1986;94:233–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1986.tb01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerdpon D, Sirirungrojying S. A clinical study of oral tori in southern Thailand: Prevalence and the relation to parafunctional activity. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1999.eos107103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Topazian DS, Mullen FR. Continued growth of a torus palatinus. J Oral Surg. 1977;35:845–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorsky M, Raviv M, Kfir E, Moskona D. Prevalence of torus palatinus in a population of young and adult Israelis. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41:623–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(96)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basha S, Dutt SC. Buccal-sided mandibular angle exostosis-A rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2011;2:237–9. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.86476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephen TS, Robert CF, Leslie ST. In: Principle and Practice of Oral Medicine. 1st ed. WB Saunders Company: Philadelphia; 1984. Evaluation and management of diseases of the oral mucosa; pp. 476–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruce I, Ndanu TA, Addo ME. Epidemiological aspects of oral tori in a Ghanaian community. Int Dent J. 2004;54:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1983. Textbook of Oral Pathology; pp. 2–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1983. Textbook of Oral Pathology; pp. 674–718. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bathla S, editor. In: Periodontics Revisited. 1st ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2011. Resective osseous surgery; pp. 366–70. [Google Scholar]