Abstract

Background

Rickettsias cause a wide spectrum of tick-, flea-, or mite-borne infections. Rickettsial infections have no classical manifestations and can often lead to encephalitis, which can be fatal if improperly diagnosed.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old male farmer was admitted to the hospital with fevers and a headache that had lasted for 10 days, followed by 4 days of unconsciousness, and his condition continued to deteriorate. Images showed multiple acute lesions in the brain stem, and bilateral cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres. He was finally diagnosed with endemic typhus and treated with antibiotics that resulted in improvement.

Conclusion

The present report describes a patient with a rickettsial infection and subsequent deterioration to coma because of an initial misdiagnosis. Because of the similarity to other infectious diseases, physicians should be more vigilant towards the history and radiologic results to ensure early detection and avoid complications which may prove to be fatal.

Keywords: Endemic or murine typhus, Cerebral infarction, Cerebral hemorrhage, Multiple lesions

Background

Rickettsial infections are caused by a wide spectrum of tick-, flea-, or mite-borne infections, the distribution of which is directly dependent on the arthropod vector or vectors [1]. The most common symptoms of rickettsial infections include fevers, rashes, headaches, dizziness, myalgias, arthralgias, and anorexia, with the classic clinical triad being fevers, rash, and unremitting headache [2]. Currently, there are no detailed data on the epidemiology of typhus, which is sometimes a localized outbreak [3, 4]. Previous Chinese epidemiologic data have shown that the prevalence of typhus fluctuates between 0.25 and 0.49 per 10,000 population [5]. Endemic typhus caused by Rickettsia typhi is the most common type of rickettsial infection in China and is considered to be self-limiting [6, 7]. Herein we describe the misdiagnosis of a severe case of endemic typhus that presented with multiple, diffuse lesions in the cerebral white matter.

Case presentation

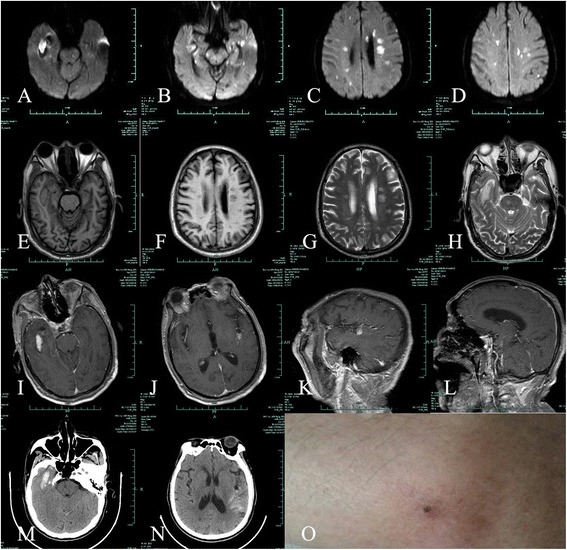

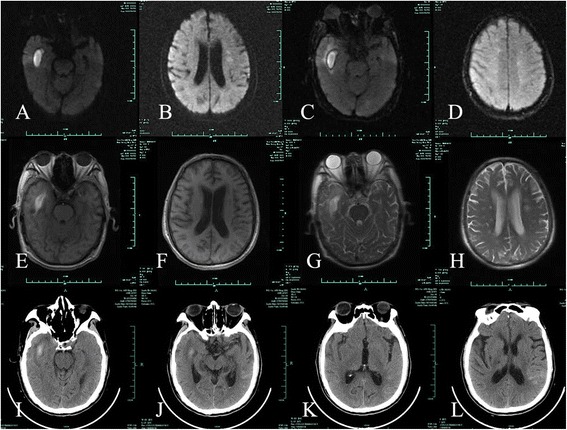

A 74-year-old male farmer from Tonglu County in Zhejiang province was admitted to the hospital for acute onset of impaired consciousness preceded by fevers and headaches lasting for days. The patient was healthy until 10 April 2014 when he presented with severe headaches, fevers, and dizziness associated with nausea. The patient had a 10-year history of hypertension and a 40-year history of alcohol and tobacco use. A physical examination and chest X-ray performed at a local clinic were unremarkable. The patient was treated symptomatically for 10 days, but without improvement. The emergency room evaluation revealed poor orientation to time, place, and person. He was febrile with a temperature of 38–39 °C. A cranial MRI showed multiple acute lesions with hyperintensity on diffusion weight imaging (DWI) involving the brain stem, and bilateral cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres (see Fig. 1a-h). Encephalitis with unknown pathogens was suspected. Empiric therapy with intravenous cefoperazone sulbactam and ribavirin was initiated. On 24 April the patient was admitted to the Neurology ward for further evaluation. A more comprehensive diagnostic work-up was carried out. A color Doppler cardiac examination was considered normal, thus ruling out subacute infective endocarditis. A lumbar puncture was performed on the hospital day 2; the CSF findings were non-diagnostic and a serum sample was obtained; the results are shown in Table 1. Despite aggressive antibiotic treatment, the patient’s neurologic condition worsened. A neurologic examination was notable for mild coma with neck stiffness, increased muscle tone throughout the body, and an extensor plantar response bilaterally. A repeat MRI with enhancement showed an increased number of intracranial lesions (Fig. 1i-l). A cranial CT done the same day indicated a right temporal lobe and left temporal parietal subarachnoid hemorrhage (Fig. 1m-n). On hospital day 3, the patient’s daughter inadvertently mentioned that her father had been to the family cemetery, which was located in a wild, undeveloped area, 10 days prior to the onset of his disease. He subsequently complained of an itch resulting from a bug bite. An eschar was noted involving the left leg (Fig. 1o). On the basis of a detailed medical history and characteristic skin changes, a rickettsial infection was tentatively diagnosed and minocycline therapy was initiated. Two weeks after the onset of symptoms, 5 mL of blood was collected from the patient with the consent of his relative and transported to the Department of Rickettsiology of the Institute of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention in Zhejiang province for testing. Serum IgG to R. typhi, R. conorii, O. tsutsugamushi, and A. phagocytophilum were detected using the IgG IFA Kit (Fuller Laboratories and Focus Diagnostics, Cypress, CA, USA). The baseline titer for rickettsial antibodies (IgG) was 1:128. Two weeks later, the rickettsial IgG antibody titer was 1:2048, and a negative serum parasite antibody test was obtained (see Table 1). DNA was extracted from blood samples using a Universal DNA Extraction Kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Dalian, China) and tested using nested PCR, targeting the groEL gene of R. prowazekii and R. typhi. Further genetic sequencing confirmed R. typhi infection; the GenBank accession number was NC_006142. Based on the test results, a final diagnosis of murine typhus was established. After a 3-week hospitalization, the patient’s condition improved markedly; specifically, the body temperature returned to normal and the patient regained consciousness. A subsequent brain MRI and CT showed a reduction in the number of intracranial lesions and resorption of the cerebral hemorrhage (Fig. 2). The patient was transferred to a local inpatient rehabilitation facility [Brief timeline of events and symptoms have been shown in Table 2].

Fig. 1.

An initial cranial MR image showing hemorrhage in the right temporal lobe, left temporal parietal subarachnoid, and multiple infarcts throughout the deep white matter. a-d: A diffusion-weighted image (DWI) shows increased intensity in central of the lesion with reduced intensity surrounding the lesion in the right temporal lobe. Multiple hyperintense lesions can be seen in the brain stem, bilateral cerebral, and cerebellar hemispheres. e-f: T1-weighted image (T1WI) shows isointensity lesions in the right temporal lobe and multiple hypointense lesions throughout deep white matter. g-h: T2-weighted image (T2WI) shows hyperintense areas in the right temporal and multiple hyperintense lesions throughout the deep white matter. i-l: enhanced T1-weighted image shows no enhanced lesions or dural meningeal enhancement. m-n: cranial CT shows right temporal lobe hemorrhage and left temporal parietal subarachnoid hemorrhage. o: an eschar present on the left calf

Table 1.

Results of laboratory tests

| å | Reference Range for Adults | Admission (April 24) | The second day (April 25) | Discharge (May 16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 131–172 | 153 | 150 | 145 |

| White cell count (per mm3) | 4.0–10 | 9.5 | 12.0 | 6.2 |

| Differential count (%) | ||||

| Neutrophils | 50.0–70.0 | 65.4 | 61.1 | 60.9 |

| Lymphocytes | 20.0–40.0 | 29.0 | 33.3 | 31.9 |

| Monocytes | 3.0–10.0 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 3.6 |

| Eosinophils | 0.5–5.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3.4 |

| Basophils | 0.0–1.0 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| C-reactive protein(mg/L) | 0.0–8.0 | 31.8 | 29.0 | 5.2 |

| CSF examination | ||||

| Cell count | ||||

| Red cell count (per mm3) | 3000 | |||

| Nucleated cell count (per mm3) | 20 | |||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 2.5–4.5 | 2.9 | ||

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 120–131 | 134 | ||

| Protein(g/L) | 0.15–0.45 | 0.57 | ||

| Liver function examination | ||||

| Glutamic pyruvic transaminase (U/L) | 5–40 | 58 | 127 | 65 |

| Glutamic oxalo-acetic transaminase (U/L) | 8–40 | 82 | 134 | 66 |

| Phosphocreatine kinase (U/L) | 38–174 | 257 | 210 | 88 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 109–245 | 522 | 412 | 300 |

| Albumin(g/L) | ||||

| HBsAg | Negative | Positive | ||

| Syphilis | Negative | Negative | ||

| Anti-HCV | Negative | Negative | ||

| Anti-HIV | Negative | Negative | ||

| TSPOT | Negative | Negative | ||

| Cytomegalovirus antibody(S/CO) | ||||

| IgM | - | |||

| IgG | +8.6 | |||

| Burkitt’s lymphoma virus antibody (S/CO) | ||||

| IgM | +1.1 | |||

| IgG | +2.9 | |||

| Herpes simplex virus type 1 antibody | ||||

| IgG | Negative | Negative | ||

| IgM | Negative | Negative | ||

| Herpes simplex virus type II antibody | ||||

| IgG | Negative | Negative | ||

| IgM | Negative | Negative | ||

| Parasitic antibody | ||||

| Paragonimus | Negative | Negative | ||

| Schistosoma japonicum | Negative | Negative | ||

| Sparganum mansoni | Negative | Negative | ||

| Toxoplasma gondii | Negative | Negative | ||

| Cysticercus cellulosae | Negative | Negative | ||

| Hydatid cyst | Negative | Negative | ||

| Serum IgG to rickettsial antibody | (April 28) | (May 12) | ||

| R. typhus | Negative | 1:128 | 1:2048 | |

| R. conorii | Negative | Negative | ||

| O. tsutsugamushi | Negative | 1:32 | 1:128 | |

| A. phagocytophilum | Negative | Negative |

Fig. 2.

A repeat MR image following treatment showing a reduced number of intracranial lesions and subsequent absorption of cerebral hemorrhage. a-b: DWI shows hyperintense lesions in the right temporal lobe and a reduced number of hypointense lesions. c-d: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) shows hyperintense lesions in the right temporal lobe and hyperintense lesions in the deep white matter. e-f (T1WI) and g-h(T2WI): also shows hyperintensity lesions in the right temporal lobe reduced numbers of leseions in the deep white matter. i-l: cranial CT shows high-density lesions in the right temporal lobe and left temporal parietal subarachnoid; the volume of cerebral hemorrhage has been reduced

Table 2.

Timeline of events and symptoms

| Time | Clinical events and symptoms |

|---|---|

| 2014-4-10 | Onset of disease |

| 2014-4-20 | Date of emergency room visit |

| 2014-4-24 | Admission day |

| 2014-4-24 | Color Doppler cardiac examination |

| 2014-4-25 | Date of lumber puncture |

| 2014-4-26 | Initiation of minocycline therapy |

| 2014-4-28 | Baseline rickettsial antibody testing |

| 2014-4-28 | Parasite antibody testing |

| 2014-5-12 | Serial rickettsial antibody testing |

| 2014-5-16 | Discharge day |

Discussion and conclusions

In China, R. typhi is the leading cause for endemic murine typhus, which is primarily transmitted by the rat flea [7]. Human murine typhus infection is characterized by high fevers, a skin rash, and a combination of a variety of symptoms, such as acute hepatitis, pneumonia, and meningitis. The patient described herein presented with fevers, headaches, dizziness, and coma. Because the patient did not have a rash, which is a typical sign of a rickettsial infection, the condition was initially misdiagnosed at the local hospital.

The unique clinical features of this patient included the following: 1) an elderly hypertensive male with a history of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption; 2) a 2-week incubation period with a lack of any observable skin rashes and a rapidly deteriorating physical condition; and 3) imaging results that showed multiple cerebral infarctions in the white matter together with intra-cerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. On admission, we first ruled out infective endocarditis based on the negative echocardiographic findings. Second, considering the fevers, headaches, elevated C-reactive protein level, and multiple intracranial lesions, meningoencephalitis was thought to be a likely diagnosis. The presence of an eschar together with an insect bite history and positive serum rickettsia-specific antibody tests, led to the final diagnosis of murine typhus complicated by pneumonia, cerebral infarction, and intracranial and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

The correct diagnosis was delayed due to the absence of any skin rashes, although the absence of rashes has been described in 10 % of reported cases [8, 9]. The pathologic features of endemic typhus include systemic vasculitis, which can induce damage to multiple organs and the brain. Rickettsia typhi proliferates and spreads via the blood stream causing injury to endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, thus resulting in vasculitis. The infection can also involve cerebral arteries and lead to brain damage [10, 11]. Vascular injury is the pathophysiologic basis for meningoencephalitis and a skin rash. The probable mechanism leading to infarction may be caused by small artery spasm or occlusion, and hemorrhage caused by increased vascular permeability due to the infection.

The neuroimaging results correlated with the pathologic findings of cerebral vasculitis, infarctions, and arteriolar thrombonecrosis [12, 13]. Cranial CT scans of rickettsia-infected patients can be normal [14] or show cerebral infarction. MR imaging findings in typhus patients have been previously shown to include focal arterial infarctions, diffuse edema, meningeal enhancement, and the presence of prominent perivascular spaces [12, 15]. In our case, the cranial CT results at the local hospital showed no cerebral infarction or hemorrhage, and the follow-up MR imaging showed multiple white matter lesions, suggesting the presence of infarction, and intracranial and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Similar MR imaging results have been described in patients with cryptococcosis and Lyme disease, which are also characterized by cerebral vasculitis [16, 17]. A study showed that 67 % of patients with abnormal neuroimaging ultimately returned to normal neurologic status and 93 % showed normal imaging after antibiotic treatment [18]. The patient regained consciousness after 2 weeks of antibiotic treatment and was able to walk unassisted after 1 month of therapy.

From the current case and literature review we concludes the following: 1) The medical history and disease evolution are key to the clinical diagnosis of murine typhus. This elderly male farmer presented with a rash that was initially overlooked. 2) Rickettsia typhi involving the endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells resulting in vasculitis not only lead to brain injury, but also cause multisystem organ failure. The imaging studies showed multiple infarctions, edema, and hemorrhage, which are rare in this type of case.3) The proper therapeutic treatment for rickettsial infections is simple and effective with a good prognosis due to early diagnosis.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZX contributed to manuscript writing and interpretation of the data. YH and QL contributed to acquisition and interpretation of the data. XC contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. XL contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ziqi Xu, Email: zyxuziqi@zju.edu.cn.

Xiongchao Zhu, Phone: 0086-13858192341, Email: sunnydays163@163.com.

Qunying Lu, Email: lqycdc@163.com.

Xia Li, Email: lix992@yahoo.com.cn.

Yewen Hu, Email: zysnhu5101@163.com.

References

- 1.Raoult D, Roux V. Rickettsioses as paradigms of new or emerging infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10(4):694–719. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qi Y, Xiong X, Wang X, Duan C, Jia Y, Jiao J, et al. Proteome analysis and serological characterization of surface-exposed proteins of Rickettsia heilongjiangensis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ya HX, Zhang HL, Zhou JH, Duan HX, Zhao XZ, et al. An outbreak of endemic typhus in Baoshan city, Yunnan province. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2011;32(1):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang WH, Dong T, Zhang HL, Wang SW, Yu HL, Zhang YZ, et al. Murine typhus in drug detoxification facility, Yunnan Province, China, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(8):1388–90. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.120060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan MY, Walker DH, Yu SR, Liu QH. Epidemiology and ecology of rickettsial diseases in the People’s Republic of China. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9(4):823–40. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.4.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang LJ, Fu XP, He JR. Analysis on the epidemic characteristics of typhus from 1994 to 2003 in China. Chin Prev Med. 2005;6:415–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumler JS, Taylor JP, Walker DH. Clinical and laboratory features of murine typhus in south Texas, 1980 through 1987. JAMA. 1991;266(10):1365–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03470100057033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Fan M. Progress in the study of spotted fever in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1999;20(2):71–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer JJ. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. When and why to consider the diagnosis. Postgrad Med. 1990;87(4):109–18. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1990.11704599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker DH, Parks FM, Betz TG, Taylor JP, Muehlberger JW. Histopathology and immunohistologic demonstration of the distribution of Rickettsia typhi in fatal murine typhus. Am J Clin Pathol. 1989;91(6):720–4. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/91.6.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raby E, Dyer JR. Endemic (murine) typhus in returned travelers from Asia, a case series: clues to early diagnosis and comparison with dengue. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88(4):701–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz DA, Dworzack DL, Horowitz EA, Bogard PJ. Encephalitis associated with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985;109(8):771–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorman RJ, Saxon S, Snead OC., 3rd Neurologic sequelae of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Pediatrics. 1981;67(3):354–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirk JL, Fine DP, Sexton DJ, Muchmore HG. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. A clinical review based on 48 confirmed cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69(1):35–45. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horney LF, Walker DH. Meningoencephalitis as a major manifestation of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. South Med J. 1988;81(7):915–8. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198807000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tien RD, Chu PK, Hesselink JR, Duberg A, Wiley C. Intracranial cryptococcosis in immunocompromised patients: CT and MR findings in 29 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12(2):283–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez RE, Rothberg M, Ferencz G, Wujack D. Lyme disease of the CNS: MR imaging findings in 14 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11(3):479–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonawitz C, Castillo M, Mukherji SK. Comparison of CT and MR features with clinical outcome in patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(3):459–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]