Abstract

We sought to understand smokers’ perceived likelihood of health problems from using cigarettes and four non-cigarette tobacco products (NCTPs: e-cigarettes, snus, dissolvable tobacco, and smokeless tobacco). A US national sample of 6,607 adult smokers completed an online survey in March 2013. Participants viewed e-cigarette use as less likely to cause lung cancer, oral cancer, or heart disease compared to smoking regular cigarettes (all p < .001). This finding was robust for all demographic groups. Participants viewed using NCTPs other than e-cigarettes as more likely to cause oral cancer than smoking cigarettes but less likely to cause lung cancer. The dramatic increase in e-cigarette use may be due in part to the belief that they are less risky to use than cigarettes, unlike the other NCTPs. Future research should examine trajectories in perceived likelihood of harm from e-cigarette use and whether they affect regular and electronic cigarette use.

Keywords: Electronic cigarettes, Electronic nicotine delivery systems, Tobacco products, Risk perceptions, Health behavior

Introduction

Traditional cigarettes remain the most popular tobacco product in the US; 18 % of US adults were current smokers in 2012 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). However, many other non-cigarette tobacco products (NCTPs) are currently available in the US market, including electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), snus, dissolvable tobacco, and traditional smokeless tobacco. E-cigarettes are battery-powered devices that produce vapor by heating a solution containing nicotine, humectants, and flavoring, although non-nicotine versions are available. Snus are packets of moist tobacco that users place between their gums and cheeks. Dissolvable tobacco typically comes in the form of sticks, strips, or orbs (aspirin-sized tablets of tobacco).

These non-cigarette tobacco products vary in their popularity. The percentage of US adults who have tried e-cigarettes in the past (“ever users”) rose from 1 % in 2009 (Regan et al., 2013) to 15 % in 2013 (Pepper et al., 2014), and rates are higher among smokers. Half of current smokers in a 2013 nationally representative US survey had ever tried e-cigarettes, and 80 % of e-cigarette ever users also smoked cigarettes (Emery, 2013). In contrast, about 5 % of US adults surveyed in 2012–2013 had ever tried snus, and fewer than 1 % had ever tried dissolvable tobacco (Agaku et al., 2014). More people in the US (18 %) have tried traditional smokeless tobacco than have tried e-cigarettes, snus, and dissolvable tobacco (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). While rates of cigarette smoking among US adults have declined, rates of use of non-cigarette tobacco products, especially e-cigarettes, have increased (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; Lee et al., 2014; Pepper & Brewer, 2014; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014).

Because products like e-cigarettes, snus, dissolvable tobacco, and traditional smokeless tobacco do not rely on combustion, they do not produce many of the same harmful chemicals and particles that regular cigarettes do and are therefore considered by scientists to be less dangerous (Hecht, 2003; Levy et al., 2004; Royal College of Physicians, 2007). However, non-combustible tobacco products are not entirely without potential harm. For example, certain models of e-cigarettes have been found to contain carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamines and other harmful constituents (Orr, 2014), and newer models of e-cigarettes with higher voltage batteries can produce formaldehyde at levels equivalent to combustible cigarettes (Kosmider et al., 2014). Some researchers are also concerned about the long-term impact of inhaling humectants like propylene glycol (Varughese et al., 2005).

The degree to which the public believes that NCTPs are less harmful than regular cigarettes could affect the prevalence of their use. Expectancy value theories like the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, 1974), as well as past studies examining a variety of behaviors such as vaccination (Brewer et al., 2007) and cancer screening (Moser et al., 2007), suggest that perceived risk can motivate health behavior. Research shows that these beliefs can affect smoking behavior, although not consistently. For example, concern about the health consequences of smoking motivates many smokers to try to quit (Costello et al., 2012), and some smokers switched to “light” cigarettes because they believed these were healthier than non-light cigarettes (Cummings et al., 2004). However, across multiple prospective studies, the stated reason for wanting to quit smoking (i.e., health concerns versus other concerns) was rarely related to success in quitting (McCaul et al., 2006). Thus, we need to understand whether smokers perceive NCTPs to be less harmful than cigarettes and, as a result, use them more often.

We sought to understand how US adult smokers perceived the risks of using cigarettes and NCTPs. We focused on smokers because they are more likely than non-smokers to use NCTPs. First, we hypothesized that smokers would view e-cigarettes as less likely to cause health problems than cigarettes (Hypothesis 1). Consistent with Rogers’ diffusion of innovation model (Rogers, 2003), smokers may see a novel product (e-cigarettes) as an improved replacement for a traditional product (cigarettes) and thus would see the latter as riskier to use. Widespread e-cigarette advertising (Duke et al., 2014; Grana & Ling, 2014; Kim et al., 2014; Pepper et al., 2014) might introduce or reinforce beliefs about e-cigarettes being less harmful than cigarettes. We also hypothesized that smokers would see cigarettes as more likely to cause lung cancer than smokeless tobacco, snus, and dissolvable tobacco, but less likely to cause oral cancer (Hypothesis 2). Our reasoning was that beliefs about a tobacco product’s health risks can depend in part on how it comes into contact with the user’s body (Choi et al., 2012). Users place smokeless tobacco, snus, and dissolvable tobacco directly against the cheeks, tongue, or gums and therefore are likely to expect those products to cause cancer in those tissues. If smokers understood the central role of combustion in causing harm (Alexander, 2013), they would instead view all combustible products (not just e-cigarettes, but also smokeless tobacco, snus, and dissolvable tobacco) as less likely to cause all three of the health problems. In addition to testing these hypotheses, we conducted exploratory analyses comparing e-cigarettes to the alternative NCTPs.

Methods

Sample

The Tobacco Control in a Rapidly Changing Media Environment (TCME) project gathered data from a national sample of 17,522 US adults (6,607 current smokers, 4,160 former smokers, and 6,755 never smokers). The TCME survey, conducted online in March 2013, assessed recall of and searching for tobacco-related information, as well as the relationship between that information and tobacco use behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes. The majority of participants (75 %) were recruited from KnowledgePanel, a nationally representative online survey panel that recruits participants through random-digit dialing, supplemented by address-based sampling to capture cell phone-only households (GfK Knowledge Networks, 2014). Of 34,097 KnowledgePanel members sampled, 61 % (n = 20,907) completed the screening. Among eligible respondents (n = 13,531), 97 % (n = 13,144) completed the survey. Other participants were recruited from convenience samples of online market research panels, using quota sampling to match demographic characteristics of a nationally representative sample; response rate data from the market research panels are not available. For this study, we report data from current smokers (n = 6,607). Institutional review boards at the National Cancer Institute and the University of Illinois at Chicago approved the study.

Measures

Perceived health risks

Smokers responded to an item about the health risks of cigarettes: “How likely do you think it is that smoking cigarettes regularly would cause you to develop each of the following in the next 10 years? (If you’re not sure, please give us your best guess).” The health conditions were lung cancer, heart disease, and mouth or throat cancer (referred to as “oral cancer” hereafter). Respondents rated their likelihood of developing these health conditions on a 5-point response scale (“not at all likely” (coded as 1) to “extremely likely” (5)). We averaged the ratings of the likelihood of developing the three health conditions to create a scale (α = 0.95).

Survey software then randomly assigned smokers to receive another question about e-cigarettes, snus, dissolvable tobacco (sticks, strip, or orbs), or traditional smokeless tobacco (moist snuff, dip, spit, chew). To conserve space on the survey, participants answered this item about only one product. Participants viewed a description of the product before responding to the item. The item read “Imagine that you stopped smoking regular cigarettes and only used [product]. How likely do you think it is that using [product] regularly would cause you to develop each of the following in the next 10 years? (If you’re not sure, please give us your best guess.)” The health conditions and response scale were the same as in the parallel item about regular cigarettes. We created a composite perceived risk measure for e-cigarettes by averaging the ratings of the likelihood of developing the three health conditions for that product (α = 0.97). All of the risk perception items met the four “best practices” criteria for measuring risk perceptions as recommended by Brewer et al. (2004) because they focus on specific harms (lung cancer, heart disease, and oral cancer), identify the person at risk (the respondent), are contingent on behavior (regular use of the product), and designate a time frame (10 years).

Demographic characteristics and product use

The survey assessed participant demographics (gender, age, education, race/ethnicity, employment, region, and household income). It also assessed awareness of e-cigarettes and dissolvable tobacco (“Before today, had you ever heard of e-cigarettes?” and “Have you ever heard of dissolvable tobacco?”), as well as use of e-cigarettes (“Have you ever used an e-cigarette, even one puff?” and “Do you now use e-cigarettes some days, every day, or not at all?”) and dissolvable tobacco (“Have you ever used dissolvable tobacco products, such as Arriva, Stonewall, or Camel Orbs, Sticks, or Strips, even one time?”). We defined current use of e-cigarettes as using them every day or some days. The survey assessed quit intentions with the item “Do you plan to quit smoking for good…?” (response options: in the next 7 days, in the next 30 days, in the next 6 months, in the next year, more than 1 year from now, or I do not plan to quit smoking for good). To assess understanding of item wording and ease of responding to survey items, we conducted cognitive interviews with 16 people and then pre-tested the revised survey with 160 respondents. For all variables, we recoded missing scores (<0.5 % for each item) to the mean or mode of that item.

Data analysis

To address Hypothesis 1, we conducted within-subjects analyses, using paired t tests to compare the perceived risk of each of the three health problems for cigarettes versus e-cigarettes. To examine the robustness of the findings comparing perceived risk for cigarettes and e-cigarettes, we repeated the t tests for demographic subgroups (e.g., only males, only smokers who intended to quit smoking in the next year) using the composite risk rating as well as each of the three specific risk ratings (lung cancer, heart disease, and oral cancer).

To address Hypothesis 2, we repeated the paired t tests to compare cigarettes to smokeless tobacco, snus, and dissolvable tobacco for each of the three health problems. For the exploratory analysis comparing e-cigarettes to the alternative NCTPs we conducted a between-subjects analysis, using linear regression to examine whether the perceived risk of developing lung cancer varied by NCTP type (e-cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, snus, and dissolvable tobacco). The reference group was participants who rated the risk of e-cigarettes. We repeated the regression to look at between-subjects differences in perceived risk of developing heart disease and oral cancer. Preliminary analyses confirmed that randomization succeeded in producing groups that did not differ with respect to demographic variables and key study variables (e.g., those who were randomly assigned to answer questions about e-cigarettes did not differ from those who answered about snus).

We also examined the demographic and behavioral variables listed in Table 1 as potential correlates of the composite perceived risk measure for e-cigarettes, using bivariate linear regressions. We included variables with statistically significant bivariate relationships to perceived risk in a simultaneous multivariate linear regression model.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n = 6,607 current smokers)

| Characteristic | n | Weighted (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Respondent | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2,654 | 48.8 |

| Female | 3,953 | 51.2 |

| Age [mean (SD)] | 44.2 (15.2) | |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 365 | 9.9 |

| High school | 1,777 | 42.9 |

| Some college | 2,976 | 34.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 1,489 | 13.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5,179 | 68.7 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 535 | 12.6 |

| Non-Hispanic, other/multiple | 412 | 6.3 |

| Hispanic | 481 | 12.4 |

| Employment | ||

| Working | 3,380 | 53.6 |

| Not working: laid off or looking for work | 855 | 14.2 |

| Not working: retired, disabled, or other | 2,372 | 32.2 |

| Intention to quit smoking | ||

| In the next year | 3,683 | 53.7 |

| More than 1 year from now | 918 | 15.0 |

| Do not plan to quit | 2,006 | 31.3 |

| E-cigarette awareness and use | ||

| Not aware | 296 | 5.1 |

| Aware but never tried | 2,969 | 44.7 |

| Former user | 1,876 | 29.4 |

| Current user | 1,466 | 20.9 |

| Dissolvable tobacco awareness and use | ||

| Not aware | 4,667 | 71.2 |

| Aware but never used | 1,493 | 22.5 |

| Have used | 447 | 6.3 |

| Household | ||

| Region | ||

| Midwest | 1,657 | 24.3 |

| Northeast | 1,123 | 17.4 |

| South | 2,305 | 39.9 |

| West | 1,522 | 18.4 |

| Household income | ||

| < $25,000 | 2,038 | 29.2 |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 1,983 | 26.4 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 1,313 | 19.1 |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 687 | 14.9 |

| $100,000 or more | 586 | 10.5 |

Percentages are weighted, and n’s are unweighted

Analyses were run in Stata Version 12. Frequencies are unweighted. Percentages and all other analyses used the “svy” command and post-stratification weights to adjust for the representativeness of the sample compared to the US population and the sampling design, including the combination of probability and non-probability samples. We report standardized regression coefficients as betas (β). Statistical tests were two-tailed with a critical alpha of .05.

Results

Of current smokers (n = 6,607) in our sample, most were non-Hispanic White (69 %) (Table 1). About half were female (51 %), had at least some college education (47 %), and had an annual household income over $50,000 (45 %). The mean age was 44 (SD 15, range 18–94). Half had tried e-cigarettes at least once, and 21 % currently used them. Only 6 % had ever tried dissolvable tobacco products. Most respondents intended to quit smoking cigarettes in the next year (54 %) or more than 1 year from now (15 %).

Comparison of e-cigarettes to cigarettes (Hypothesis 1)

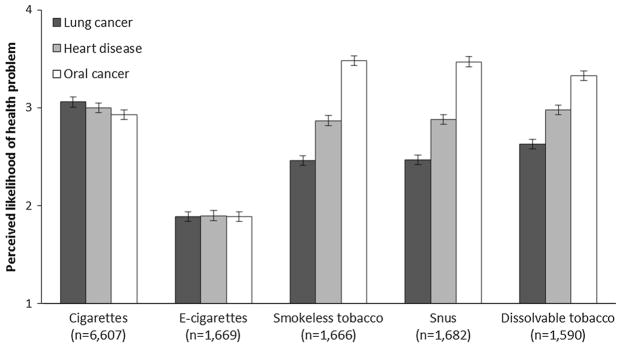

Participants perceived e-cigarettes as less likely to cause lung cancer (mean difference 1.17 between values for e-cigarettes and cigarettes, p < .001), heart disease (1.07, p < .001), and oral cancer (1.04, p < .001) compared to regular cigarettes (Fig. 1). The belief that e-cigarettes were less harmful than regular cigarettes was robust. It persisted in each tested demographic subgroup, all p < .001: men (mean difference 1.09 between values for e-cigarettes and regular cigarettes), women (1.10), high school or less education (1.20), some college or more education (0.96), non-Hispanic Whites (1.06), non-Hispanic Blacks (1.56), non-Hispanics of other or multiple races (0.78), Hispanics (0.91), those with household incomes below $50,000 (1.14), and those with household incomes of $50,000 or more (1.03). It also persisted among smokers who plan to quit in the next year (1.25), smokers who plan to quit more than 1 year from now (1.05), smokers who do not plan to quit (0.86), ever users of e-cigarettes (1.06), and never users of e-cigarettes (1.09). The pattern was the same for each individual health condition. That is, for every subgroup, participants in that group believed that e-cigarettes were less likely to cause lung cancer, less likely to cause heart disease, and less likely to cause oral cancer than cigarettes (all comparisons p < .001).

Fig. 1.

Perceived risks of using tobacco products. Error bars represent standard errors

Comparison of alternative non-cigarette tobacco products to cigarettes (Hypothesis 2)

Participants believed that smokeless tobacco was less likely to cause lung cancer than cigarettes (mean difference 0.51 between values for smokeless tobacco and cigarettes, p < .001), equally likely to cause heart disease (0.06, p = .13), and more likely to cause oral cancer (0.61, p < .001) (Fig. 1). Similarly, compared to cigarettes, participants perceived snus as less likely to cause lung cancer (0.58, p < .001), equally likely to cause heart disease (0.07, p = .14), and more likely to cause oral cancer (0.58, p < .001). Participants also believed that dissolvable tobacco was less likely to cause lung cancer (0.54, p < .001) and more likely to cause oral cancer (0.27, p < .001) than cigarettes, but they believed that dissolvable tobacco was less likely to cause heart disease compared to regular cigarettes (0.17, p < .001).

Comparisons of e-cigarettes and alternative non-cigarette tobacco products (exploratory between-groups analysis)

Smokers who were randomly assigned to answer items about e-cigarettes believed that they were less likely to develop lung cancer from using that product than did smokers who were randomly assigned to answer items about using smokeless tobacco, snus, or dissolvable tobacco (mean differences 0.57, 0.58, and 0.74, respectively; all between-groups comparisons p < .001) (Fig. 1; Table 2). They similarly perceived greater likelihood of developing heart disease from other non-combustible products than from e-cigarettes (mean differences 0.97 for smokeless tobacco, 0.98 for snus, and 1.08 for dissolvable tobacco; all comparisons p < .001). Smokers who were randomly assigned to answer items about smokeless tobacco, snus, and dissolvable tobacco believed they were more likely to develop cause oral cancer than smokers who answered about e-cigarettes (mean differences 1.59, 1.58, and 1.44, respectively; all comparisons p < .001).

Table 2.

Comparison of perceived risks by type of product used (n = 6,607)

| Mean (SD) | β | |

|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer | ||

| E-cigarettes | 1.89 (1.03) | |

| Smokeless tobacco | 2.46 (1.27) | 0.19*** |

| Snus | 2.47 (1.30) | 0.20*** |

| Dissolvable tobacco | 2.63 (1.33) | 0.25*** |

| Heart disease | ||

| E-cigarettes | 1.90 (1.04) | |

| Smokeless tobacco | 2.87 (1.26) | 0.32*** |

| Snus | 2.88 (1.27) | 0.33*** |

| Dissolvable tobacco | 2.98 (1.27) | 0.35*** |

| Oral cancer | ||

| E-cigarettes | 1.89 (1.03) | |

| Smokeless tobacco | 3.48 (1.22) | 0.50*** |

| Snus | 3.47 (1.22) | 0.50*** |

| Dissolvable tobacco | 3.33 (1.26) | 0.45*** |

Higher mean scores indicate higher perceived likelihood of a health problem (1 = not at all likely—5 = extremely likely)

p < .001

Correlates of perceived risks of e-cigarette use

Multivariate analysis of perceived risks of e-cigarette use found that women perceived themselves as more likely to develop health problems from using e-cigarettes (β = 0.11, p < .01) than men (Table 3). Compared to non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic participants of other or multiple races believed themselves to be more at risk from using e-cigarettes (β = 0.08, p < .05), as did Hispanic participants (β = 0.14, p < .01). Neither intention to quit smoking, nor use of e-cigarettes, was associated with perceptions of the health risks of e-cigarettes.

Table 3.

Correlates of perceived risk of using e-cigarettes (n = 1,669)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Bivariate β | Multivariate β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent | |||

| Gender | |||

| Male (ref) | 1.80 (0.86) | ||

| Female | 2.00 (1.22) | 0.10* | 0.11** |

| Age | −0.07 | ||

| Education | |||

| Less than high school (ref) | 1.96 (0.85) | ||

| High school | 1.85 (0.76) | −0.05 | |

| Some college | 1.93 (1.21) | −0.01 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 1.93 (1.49) | −0.01 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White (ref) | 1.83 (1.08) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.83 (0.85) | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Non-Hispanic, other/multiple | 2.15 (1.12) | 0.07* | 0.08* |

| Hispanic | 2.27 (0.85) | 0.13** | 0.14** |

| Employment | |||

| Working (ref) | 1.94 (0.97) | ||

| Not working: laid off or looking for work | 1.93 (1.16) | −0.00 | |

| Not working: retired, disabled, or other | 1.82 (1.08) | −0.06 | |

| Intention to quit smoking | |||

| In the next year (ref) | 1.81 (0.97) | ||

| More than 1 year from now | 1.97 (1.12) | −0.06 | |

| Do not plan to quit | 1.79 (0.91) | −0.08 | |

| E-cigarette awareness and use | |||

| Not aware or never used (ref) | 1.86 (0.99) | ||

| Former user | 1.89 (0.99) | 0.01 | |

| Current user | 1.99 (1.22) | 0.05 | |

| Household | |||

| Region | |||

| Midwest (ref) | 1.90 (1.03) | ||

| Northeast | 1.81 (0.94) | −0.04 | |

| South | 1.88 (0.97) | −0.01 | |

| West | 2.03 (1.26) | 0.05 | |

| Household income | |||

| < $25,000 (ref) | 1.89 (1.16) | ||

| $25,000–$49,999 | 1.97 (1.13) | 0.04 | |

| $50,000 –$74,999 | 1.89 (0.96) | 0.00 | |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 1.72 (0.80) | −0.06 | |

| $100,000 or more | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.04 | |

Multivariate model contained correlates significant (p < .05) in bivariate models

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Discussion

As use of e-cigarettes increases, it is important to better understand what people think about the potential harms of using e-cigarettes relative to cigarettes and other NCTPs. Our national study found that smokers believed that regular cigarettes were more likely than e-cigarettes to cause lung cancer, oral cancer, and heart disease. In contrast, smokers’ beliefs about the harms of the other three NCTPs relative to cigarettes varied by health condition. Comparing across groups, we observed that smokers saw e-cigarettes as less risky than the other NCTPs.

The finding that smokers believed that e-cigarettes were less likely to cause health problems than regular cigarettes supports our first hypothesis. We expect that that this belief reflects factors that are specific to e-cigarettes (e.g., advertising) as well as factors that relate more generally to new and innovative products. Exposure to pro-e-cigarette messages could drive the impression that e-cigarettes are safer than cigarettes. Indeed, two of the most common ways that current smokers report learning about e-cigarettes are e-cigarette users and advertisements on television, both of which likely highlight the advantages of the product (Pepper et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2013). Positive messages about e-cigarettes also appear regularly on YouTube (Paek et al., 2013) and in online ads (Cobb et al., 2013; Grana & Ling, 2014). E-cigarettes’ status as an innovative product might reinforce their positive characteristics. Rogers’ diffusion of innovation model suggests that smokers might hold a positive view about e-cigarettes’ level of harm because the product is novel and thus perceived to have relative advantages (e.g., reduced health risk) over cigarettes, the product they are replacing (Rogers, 2003). Snus and dissolvable tobacco, although also innovative, may be too different from cigarettes for smokers to consider them a replacement. Thus smokers may not hold consistent views that these products were less harmful than cigarettes. Such misperceptions suggest that participants did not understand the role of combustion in creating smoking-related harms (Hecht, 2003; Levy et al., 2004; Royal College of Physicians, 2007). If participants had understood this, they would have described all four NCTPs as less harmful than regular cigarettes for all health conditions.

The finding that participants believed that snus and dissolvable and smokeless tobacco were more likely to cause oral cancer than cigarettes, although this is not objectively true (Royal College of Physicians, 2007), supports our second hypothesis. We speculate that the belief derives from the products’ mode of nicotine delivery and the physical act of use. In a 2010 focus group study, young adults expressed particular concern about snus and dissolvable tobacco because those products come in direct contact with the mouth, and thus they perceived them to be likely to cause oral cancer and gastrointestinal disease (Choi et al., 2012). People also place traditional smokeless tobacco directly in their mouths, so they might perceive it to have similar harms. Additional support for our second hypothesis, that mode of nicotine delivery affects perceived health risk, comes from the finding that smokers also viewed regular cigarettes as more likely to cause lung cancer than oral cancer. Respondents may have perceived that cigarettes’ primary mode of contact, unlike snus, dissolvable tobacco, or smokeless tobacco, is inhaled smoke. That smokers viewed smokeless tobacco, snus, and regular cigarettes as equally likely to cause heart disease is consistent with this hypothesis; mode of tobacco administration has no intuitive connection to the heart.

Our exploratory analysis, based on between-group comparisons, found that smokers perceived e-cigarettes to be less harmful than snus, dissolvable tobacco, and smokeless tobacco. A recent survey of university students reported similar findings, although the report did not explicitly test these comparisons (Latimer et al., 2013). The perceived differences between e-cigarettes and the alternative NCTPs may reflect exposure to positive messages in increasingly prevalent e-cigarette marketing (Kim et al., 2014).

We found variation in individuals’ beliefs about e-cigarettes’ healthfulness. Women believed that e-cigarettes were more likely to cause health problems than did men. Women perceive themselves to be at higher risk of developing smoking-related cancer (Oncken et al., 2005), perhaps because men are socialized to see themselves as invulnerable (Courtenay, 2011). Non-Hispanic Whites perceived themselves at lower risk of experiencing health problems from e-cigarettes than did some other racial and ethnic groups. These differences could reflect participants’ recognition that racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to die from some tobacco-related illnesses than non-His-panic Whites (American Cancer Society, 2013).

Past use of e-cigarettes and intention to quit smoking were not related to beliefs about the riskiness of e-cigarettes, but we cannot conclude that these variables are unrelated. Only longitudinal or experimental studies can confirm a behavior motivation hypothesis (Brewer et al., 2004), in this case that e-cigarette risk perceptions cause a change in e-cigarette use. Another potential limitation is that our study asked about cancer and heart disease, but not other conditions like emphysema, and only used single item measures of risk for each illness. Finally, the combination of probability and non-probability samples is a potential limitation, although the large probability sample helped us to properly weight data from the non-probability sample. In spite of these limitations, the data present a clear picture that smokers perceive the health risks of e-cigarettes to be lower than both traditional and alternative tobacco products.

Our findings suggest several avenues for public health and regulatory action. First, most participants incorrectly believed that snus, dissolvable tobacco, and traditional smokeless tobacco were more likely to cause oral cancer than cigarettes. Thus, smokers who are unable or unwilling to quit smoking might avoid switching to these smokeless products, when in fact switching to these products would be a potential harm reduction strategy. Public health messages should communicate accurate information about the utility of smokeless tobacco as a harm reduction option, although such messages will need to be extremely careful not to encourage switching over quitting or inadvertently “selling” smokeless tobacco to non-smokers. Second, although most participants correctly perceived that e-cigarettes are generally less harmful than cigarettes, their ratings of the risks of using e-cigarettes may not be accurate. Public health education campaigns will need to stay up to date with the changing products and latest research on their health effects in order to keep the public informed.

Third, understanding beliefs about the health risks of e-cigarettes could assist with future smoking cessation interventions. Should studies show that using e-cigarettes aids smoking cessation, drawing attention to the comparison of their health risks to those of regular cigarettes could be a valuable intervention approach for encouraging cessation. Finally, the US Food and Drug administration is in the process of shaping new regulations for e-cigarettes and dissolvable tobacco (Food and Drug Administration, 2014), including warning labels. By codifying smokers’ beliefs about the health risks of these products, this study’s findings could inform the development of labels that clarify or correct perceptions.

The widespread belief that e-cigarettes are less harmful than other products may be one of the key factors driving their rise in popularity. Other factors include e-cigarettes’ ability to deliver nicotine efficiently (Vansickel & Eissenberg, 2013) and mimic some aspects of the physical experience of smoking (Barbeau et al., 2013), as well as the wide variety of available flavors (Farsalinos et al., 2013) and personalization options (Brown & Cheng, 2014; McQueen et al., 2011). Should harm perceptions, in harmony with these and other factors, play an important role in popularizing e-cigarettes, our findings suggest that use of alternative non-cigarette tobacco products, including novel ones like snus and dissolvable tobacco, are unlikely to increase in the same manner as e-cigarettes. While using non-combustible tobacco is less risky than cigarette smoking, few data exist on the short- and long-term health effects of e-cigarettes in particular. Additional research is needed to quantify both the absolute risk of using e-cigarettes, as well as the risk of using e-cigarettes relative to that of smoking cigarettes.

The context of e-cigarette research and public health practice is changing because e-cigarette technology is advancing rapidly. Compared to first-generation models, newer models often have “tanks” that can hold more e-liquid, larger rechargeable batteries, and the option to “drip” e-liquid directly onto the atomizer instead of using a cartridge (Brown & Cheng, 2014). Variations in design affect how the product is used (Brown & Cheng, 2014) as well as its safety profile (Kosmider et al., 2014). Thus it is important to consider whether perceptions of risk vary by product type and are sensitive to actual differences in health risks related to product design. Future research should also investigate the impact of exposure to e-cigarette advertising and other media on beliefs about e-cigarettes’ harm, how beliefs about e-cigarettes’ harm change over time, and whether those beliefs affect smokers’ trajectories of e-cigarette and regular cigarette use. Such research could help the public health community identify and deliver appropriate messages about e-cigarettes’ safety and inform future product regulation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Drs. Jessica Pepper, Sherry Emery, Kurt Ribisl, Christine Rini, and Noel Brewer declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

Contributor Information

Jessica K. Pepper, Email: jkadis@unc.edu, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7440, USA

Sherry L. Emery, Email: slemery@uic.edu, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Kurt M. Ribisl, Email: kurt_ribisl@unc.edu, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7440, USA

Christine M. Rini, Email: rini@email.unc.edu, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7440, USA

Noel T. Brewer, Email: ntb@unc.edu, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA. Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7440, USA

References

- Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, Bunnell R, Ambrose BK, Day HR. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2012–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2014;63:542–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander T. Communicating about harmful and potentially harmful constituents in tobacco and tobacco smoke: potential opportunities and challenges. Paper presented at the Joint Meeting of the Risk Communication Advisory Committee (RCAC) & the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC); Silver Spring, MD. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2013. Atlanta, GA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau AM, Burda J, Siegel M. Perceived efficacy of e-cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy among successful e-cigarette users: A qualitative approach. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2013;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychology. 2007;26:136–145. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer NT, Weinstein ND, Cuite CL, Herrington JE. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:125–130. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Cheng JM. Electronic cigarettes: product characterisation and design considerations. Tobacco Control. 2014;23:ii4–ii10. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Fabian L, Mottey N, Corbett A, Forster J. Young adults’ favorable perceptions of snus, dissolvable tobacco products, and electronic cigarettes: Findings from a focus group study. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:2088–2093. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb NK, Brookover J, Cobb CO. Forensic analysis of online marketing for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tobacco Control. 2013 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051185. (advance online publication) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello MJ, Logel C, Fong GT, Zanna MP, McDonald PW. Perceived risk and quitting behaviors: Results from the ITC 4-country survey. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2012;36:681–692. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.5.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Dying to be men: Psychosocial, environmental, and biobehavioral directions in promoting the health of men and boys. New York: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KM, Hyland A, Bansal MA, Giovino GA. What do Marlboro Lights smokers know about low-tar cigarettes? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:S323–S332. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke JC, Lee YO, Kim AE, Watson KA, Arnold KY, Nonnemaker JM, et al. Exposure to electronic cigarette television advertisements among youth and young adults. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e29–e36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery S. It’s not just message exposure anymore: A new paradigm for health media research. Paper presented at the Presented at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Baltimore, MD. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Tsiapras D, Kyrzopoulos S, Spyrou A, Voudris V. Impact of flavour variability on electronic cigarette use experience: An internet survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013;10:7272–7282. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10127272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Regulations on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products. Federal Register. 2014;79:23141–23207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GfK Knowledge Networks. KnowledgePanel overview. 2014 Retrieved January 13, 2014, from http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/knpanel/KNPanel-Design-Summary.html.

- Grana RA, Ling PM. “Smoking revolution”: A content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS. Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3:733–744. doi: 10.1038/nrc1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AE, Arnold KY, Makarenko O. E-cigarette advertising expenditures in the U.S., 2011–2012. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46:409–412. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Fik M, Knysak J, Zaciera M, Kurek J, Goniewicz ML. Carbonyl compounds in electronic cigarette vapors: Effects of nicotine solvent and battery output voltage. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu078. (advance online publication) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer LA, Batanova M, Loukas A. Prevalence and harm perceptions of various tobacco products among college students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt174. (advance online publication) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: Cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Preventive Medicine. 2014;62C:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Mumford EA, Cummings KM, Gilpin EA, Giovino G, Warner KE. The relative risks of a low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco product compared with smoking cigarettes: Estimates of a panel of experts. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2004;13:2035–2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul KD, Hockemeyer JR, Johnson RJ, Zetocha K, Quinlan K, Glasgow RE. Motivation to quit using cigarettes: A review. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Tower S, Sumner W. Interviews with “vapers”: Implications for future research with electronic cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:860–867. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser RP, McCaul K, Peters E, Nelson W, Marcus SE. Associations of perceived risk and worry with cancer health-protective actions: Data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12:53–65. doi: 10.1177/1359105307071735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncken C, McKee S, Krishnan-Sarin S, O’Malley S, Mazure CM. Knowledge and perceived risk of smoking-related conditions: A survey of cigarette smokers. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:779–784. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr MS. Electronic cigarettes in the USA: A summary of available toxicology data and suggestions for the future. Tobacco Control. 2014;23:ii18–ii22. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek HJ, Kim S, Hove T, Huh JY. Reduced harm or another gateway to smoking? Source, message, and information characteristics of e-cigarette videos on YouTube. J Health Commun. 2013 doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.821560. (advance online publication) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions, and beliefs: A systematic review. Tobacco Control. 2014;23:375–384. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper JK, Emery SL, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. How do U.S. adults find out about electronic cigarettes? Implications for public health messages. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16:1140–1144. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: Adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tobacco Control. 2013;22:19–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th edition. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model and preventive health behavior. Health Education and Behavior. 1974;2:354–386. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians. A report by the Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians, London, UK. 2007. Harm reduction in nicotine addiction: Helping people who can’t quit. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. 2012 Retrieved from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/population-data-nsduh.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking–50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vansickel AR, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes: Effective nicotine delivery after acute administration. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15:267–270. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varughese S, Teschke K, Brauer M, Chow Y, van Netten C, Kennedy SM. Effects of theatrical smokes and fogs on respiratory health in the entertainment industry. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2005;47:411–418. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Gamst A, Lee M, Cummins S, Yin L, Zoref L. The use and perception of electronic cigarettes and snus among the U.S. population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]