Abstract

Objective

To report 5-year results from a previously reported trial evaluating intravitreal 0.5-mg ranibizumab with prompt versus deferred (for ≥24 weeks) focal/grid laser treatment for diabetic macular edema (DME).

Design

Multicenter randomized clinical trial.

Participants

Among participants from the trial with 3 years of follow-up who subsequently consented to a 2-year extension and survived through 5 years, 124 (97%) and 111 (92%) completed the 5-year visit, in the prompt and deferred groups, respectively.

Methods

Random assignment to ranibizumab every 4 weeks until no longer improving (with resumption if worsening) and either prompt or deferred (>= 24 weeks) focal/grid laser treatment.

Main Outcome Measures

Best-corrected visual acuity at the 5-year visit.

Results

The mean change in visual acuity letter score from baseline through the 5-year visit was +7.2 letters in the prompt laser group compared with +9.8 letters in the deferred laser group (mean difference -2.6 letters, 95% confidence interval -5.5 to +0.4 letters, P = 0.09). At the 5-year visit in the prompt vs. deferred laser groups respectively, there was vision loss of ≥10 letters in 9% vs. 8%, an improvement of ≥10 letters in 46% vs. 58%, and an improvement of >15 letters in 27% vs. 38% of participants. From baseline through 5 years, 56% of participants in the deferred group did not receive laser. The median number of injections was 13 vs. 17 in the prompt and deferral groups, including 54% and 45% receiving no injections during year 4 and 62% and 52% receiving no injections during year 5, respectively.

Conclusions

Five-year results suggest focal/grid laser treatment at the initiation of intravitreal ranibizumab is no better than deferring laser treatment for ≥24 weeks in eyes with DME involving the central macula with vision impairment. While over half of eyes where laser treatment is deferred may avoid laser for at least 5 years, such eyes may require more injections to achieve these results when following this protocol. Most eyes treated with ranibizumab and either prompt or deferred laser maintain vision gains obtained by the first year through 5 years with little additional treatment after 3 years.

Introduction

In a comparative effectiveness randomized clinical trial conducted by the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net), participants with center involved diabetic macular edema (DME) and associated vision impairment were assigned randomly to intravitreal 0.5-mg ranibizumab combined with prompt or deferred (≥24 weeks) focal/grid laser treatment, 4-mg triamcinolone combined with prompt focal/grid laser treatment, or sham injections with prompt focal/grid laser treatment.1, 2 In the ranibizumab plus deferred laser group, laser was deferred for at least 24 weeks, and only added at the 24-week visit, or thereafter, if DME persisted and was not improving despite injections of ranibizumab every four weeks. Results at three years of follow-up suggested that focal/grid laser treatment at the initiation of intravitreal ranibizumab was no better and possibly worse than deferring laser treatment for ≥24 weeks with respect to visual acuity outcomes.3 This report provides additional information on the comparison of these two groups through five years. The other 2 groups assigned to sham intravitreous injection combined with prompt focal/grid laser or intravitreous corticosteroids combined with prompt focal/grid laser were given the opportunity to receive ranibizumab and thus randomized group comparisons were no longer valid; the long term results of those arms are planned for a subsequent submission for publication.

Methods

The study procedures have been reported1 previously and are summarized briefly herein. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant informed consent forms (the original study consent and extension study consent) were approved by institutional review boards. The protocol is available on the DRCR.net website (www.drcr.net; accessed June 13, 2014). In brief, participants had at least one eye with visual acuity (approximate Snellen equivalent) of 20/32 to 20/320 and DME involving the central macula. At study enrollment, 180 eyes were assigned to ranibizumab plus prompt focal/grid laser treatment and 181 to ranibizumab plus deferred laser treatment. Laser in the deferral group had to be delayed for at least 24 weeks after initiating anti-VEGF therapy. However, at or after 24 weeks, laser treatment could be given if there was persistent DME involving the central subfield on OCT that had not improved after at least 2 consecutive injections given at 4-weekly intervals. At the end of 3 years of follow-up, 132 and 136 participants, respectively, consented to participate in a two-year extension of the study. Visits occurred every 4 weeks through year 1 and then every 4 to 16 weeks through year 5 depending on protocol-defined criteria based on visual acuity, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and whether treatment for DME was given at the previous visit. An assessment for retreatment with ranibizumab, retreatment with laser, or initiation of laser treatment for the deferred group, occurred at each visit. The treatment decision was based on protocol specified criteria which have been reported previously.1

A longitudinal analysis was performed to compare visual acuity and OCT central subfield (CSF) thickness change from baseline for the 16- through the 260-week (“5-year”) visits for all eyes in the two ranibizumab groups using continuous time models assuming a linear relationship over time, and adjusting for baseline visual acuity (and baseline CSF thickness or volume for the CSF thickness and volume models respectively), using all available visit data.4 The 16 week starting time for the longitudinal models coincides with completion of four mandatory monthly injections in each group and the start of the linear trend over time; The longitudinal models were repeated adjusting for additional potential confounders (baseline CSF thickness, age, prior PRP, lens status, DR severity). Visual acuity changes were truncated to ±30 letters to minimize the effects of outliers; specifically, at various times among various participants, in 153 instances the visual acuity increased more than 30 letters and in 52 instances the visual acuity decreased more than 30 letters among 4996 visit records included in the longitudinal analyses. Generalized linear regression models were used to analyze binary visual acuity or CSF thickness outcome variables at 5 years, including estimating differences in proportions using the binomial distribution with identity link, and relative risks using the Poisson distribution with log link. OCT CSF thickness and volume measurements obtained on spectral domain machines during follow-up were converted to time domain equivalent values based on conversion equations validated in prior DRCR.net studies.5 Ocular safety data included all randomized eyes; all other analyses excluded 14 participants from one clinical site in which a majority of eyes at baseline were judged not to meet the OCT eligibility criterion of CSF thickness ≥250μm when graded manually at a central reading center.

Results

Excluding deaths, the 5-year completion rate was 76% of the 163 original participants randomized to the ranibizumab + prompt laser group and 74% of the 150 original participants randomized to the ranibizumab + deferred laser group. Because the fourth and fifth years were extensions of the original study, some patients chose not to consent to the longer follow-up. Among those consenting and surviving through 5 years, the completion rate was 97% and 92% respectively. A comparison of eyes with a 5-year exam (“completers”) to eyes without a 5-year exam (“non-completers”) is in Table 1, available at http://aaojournal.org. Some imbalances between completers versus non-completers were noted (age, prior PRP, lens status, diabetic retinopathy severity level), and these factors were included as potential confounders in the adjusted analysis noted below.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics Comparing Participants who Completed and those that did not Complete the 5-Year Visit by Treatment Group.

| Ranibizumab + prompt laser | Ranibizumab + deferred laser | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Completed | Did not complete† | Completed | Did not complete† | |

| N = 124 eyes | N = 56 eyes | N = 111 eyes | N = 70 eyes | |

| Gender: Women - N (%) | 60 (48%) | 22 (39%) | 42 (38%) | 31 (44%) |

| Age (years) - median (25th, 75th percentile) | 63 (57, 69) | 65 (55, 72) | 63 (58, 69) | 65 (58, 71) |

| Race - N (%) | ||||

| White | 92 (74%) | 39 (70%) | 79 (71%) | 55 (79%) |

| Black/African American | 19 (15%) | 11 (20%) | 18 (16%) | 7 (10%) |

| Hispanic | 8 (6%) | 6 (11%) | 12 (11%) | 6 (9%) |

| Asian | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| More than one race | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| Unknown/not reported | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Diabetes Type – N (%) | ||||

| Type 1 | 8 (6%) | 3 (5%) | 7 (6%) | 8 (11%) |

| Type 2 | 113 (91%) | 52 (93%) | 103 (93%) | 61 (87%) |

| Uncertain | 3 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Duration of Diabetes (years) - median (25th, 75th percentile) | 18 (12, 24) | 17 (13, 26) | 16 (10, 22) | 17 (12, 24) |

| HbA1c** (%) - median (25th, 75th percentile) | 7.2 (6.5, 8.3) | 7.5 (6.6, 9.0) | 7.5 (6.5, 8.3) | 7.3 (6.8, 8.3) |

| Prior Panretinal Scatter Photocoagulation - N (%) | 41 (33%) | 6 (11%) | 23 (21%) | 14 (20%) |

| Prior Treatment for DME - N (%) | 81 (65%) | 33 (59%) | 70 (63%) | 44 (63%) |

| Prior Photocoagulation for DME - N (%) | 72 (58%) | 30 (54%) | 64 (58%) | 37 (53%) |

| IOP (mmHg) - median (25th, 75th percentile) | 16 (14, 18) | 17 (15, 18) | 16 (14, 19) | 17 (14, 18) |

| Lens Status Phakic (clinical exam) - N (%) | 90 (73%) | 34 (61%) | 83 (75%) | 44 (63%) |

| E-ETDRS Visual Acuity (letter score) - median (25th, 75th percentile) | 65 (56, 73) | 65 (54, 71) | 67 (59, 73) | 62 (56, 72) |

| Central Subfield Thickness (μm) on OCT‡ - median (25th, 75th percentile) | 375 (304, 477) | 372 (318, 466) | 394 (321, 498) | 378 (292, 484) |

| Retinal Volume (mm3) on OCT‡ - median (25th, 75th percentile) | 8.4 (7.4, 9.6) | 8.5 (7.7, 9.7) | 8.4 (7.5, 9.9) | 8.3 (7.3, 9.5) |

| Retinopathy Severity Level (ETDRS Severity Scale)‡ - N (%) | ||||

| No DR/MA/Mild/Moderate NPDR | 27 (22%) | 12 (21%) | 31 (28%) | 14 (20%) |

| Moderately Severe/Severe NPDR | 50 (40%) | 28 (50%) | 44 (40%) | 25 (36%) |

| Mild/Moderate/High-risk PDR | 42 (34%) | 15 (27%) | 27 (24%) | 26 (37%) |

HbA1c = Hemoglobin A1c; DME = Diabetic macular edema; E-ETDRS© = Electronic Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; ETDRS = Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; IOP = Intraocular pressure; OCT = Optical coherence tomography; DR = Diabetic retinopathy; MA = Microaneurysms; NPDR = Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = Proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Includes not in extension study (93) vs. in extension study but did not complete 5-year visit (33) [due to deaths (19), withdrawals from the study (8), loss to follow-up (6]

Visits occurring between window 244 and 276 weeks (1708 and 1932 days) from randomization were included as 5-year visits. When more than 1 visit occurred in this window, data from the visit closest to the 5-year target date were used.

Missing for the completer and non-completers, respectively: 5 and 4.

Missing (or un-gradable) OCT and fundus photograph data as follows for the completer and non-completers, respectively: central subfield (0, 1), retinal volume (48, 31), and retinopathy severity (14, 6).

Of the 5-year completers, the median number of injections in year 4 and 5, respectively, was 0 and 0 in the ranibizumab with prompt laser group and 1 and 0 in the ranibizumab with deferred laser group. This included 54% and 45% of eyes during year 4, and 62% and 52% of eyes during year 5 that received no injections in the ranibizumab with prompt laser and deferred laser groups, respectively (Table 2). Out of a potential maximum cumulative number of 65 injections during the five years of the study, the median (IQR) number of injections was 4 fewer (13 [9, 24] versus 17 [11, 27]) in the prompt vs. deferred laser group (Table 2). The median total number of follow-up visits over five years was 38 and 40, including 4 and 5 during year 5 in the prompt and deferred laser groups, respectively (Table 2). By the 5-year visit, 44% of the eyes in the ranibizumab plus deferred laser treatment group had received at least one session of focal/grid laser treatment (Table 2). Other treatment for DME (such as intravitreous bevacizumab, Intravitreous triamcinolone, or vitrectomy) was received by 9 (7%) of the completers in the prompt laser group (7 were per protocol as futility or failure criteria had been met and 2 were not) and none in the deferred laser group.

Table 2. Visits and Treatments Prior to Five Year Visit* - Median (quartiles) or N (%).

| Ranibizumab + Prompt Laser treatment N = 124 | Ranibizumab + Deferred Laser treatment N = 111 | |

|---|---|---|

| Visit History | ||

|

| ||

| Number of visits in year one | 13 (12, 13) | 13 (12, 13) |

| Number of visits in year two | 8 (6, 11) | 10 (7, 12) |

| Number of visits in year three | 7 (4, 10) | 8 (5, 11) |

| Number of visits in year four | 5 (4, 9) | 6 (4, 9) |

| Number of visits in year five | 4 (3, 7) | 5 (3, 7) |

| Number of visits prior to five year visit | 38 (31, 47) | 40 (34, 49) |

|

| ||

| Intravitreous injection history | ||

|

| ||

| Number of injections in year one | 8 (7, 11) | 9 (6, 11) |

| Number of injections in year two | 2 (0, 5) | 3 (1, 6) |

| Number of injections in year three | 1 (0, 4) | 2 (0, 5) |

| Number of injections in year four | 0 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 4) |

| Number of injections in year five | 0 (0, 3) | 0 (0, 3) |

| Number (%) of eyes that received one or more injections in year four | 57 (46%) | 61 (55%) |

| Number (%) of eyes that received one or more injections in year five | 47 (38%) | 53 (48%) |

| Number of injections prior to five year visit | 13 (9, 24) | 17 (11, 27) |

|

| ||

| Focal/grid laser history | ||

|

| ||

| Number of focal/grid laser treatments prior to the five year visit | 3 (2, 5) | 0 (0, 2) |

| Number (%) of eyes that did not receive focal/grid laser treatment prior to the five year visit | 0 | 62 (56%) |

| Number (%) of eyes that did not receive focal/grid laser treatment in year five | 112 (90%) | 108 (97%) |

Limited to study participants completing the 5-year visit

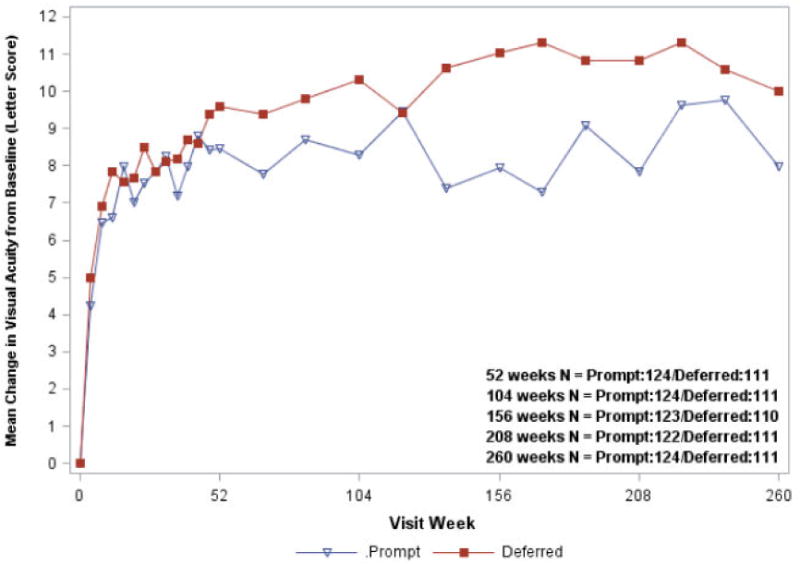

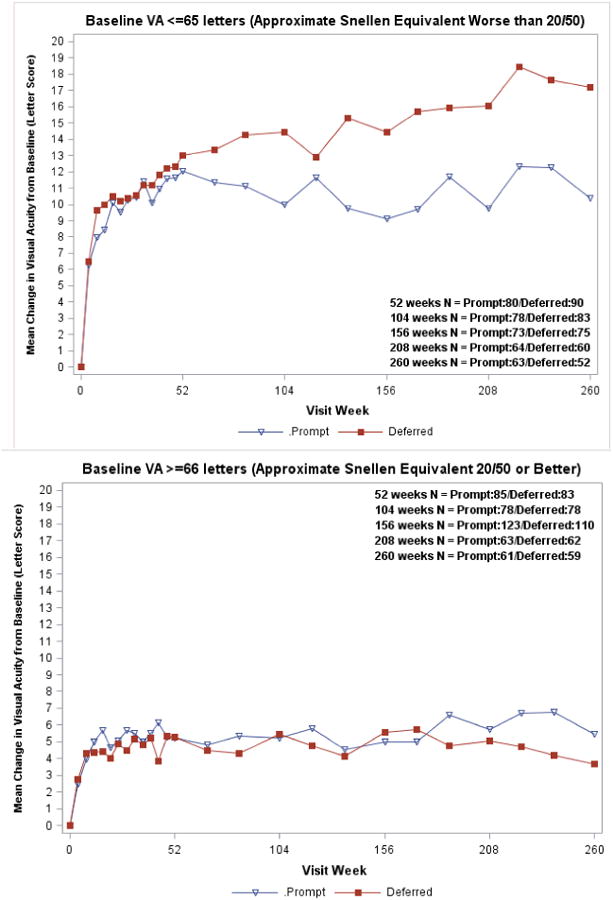

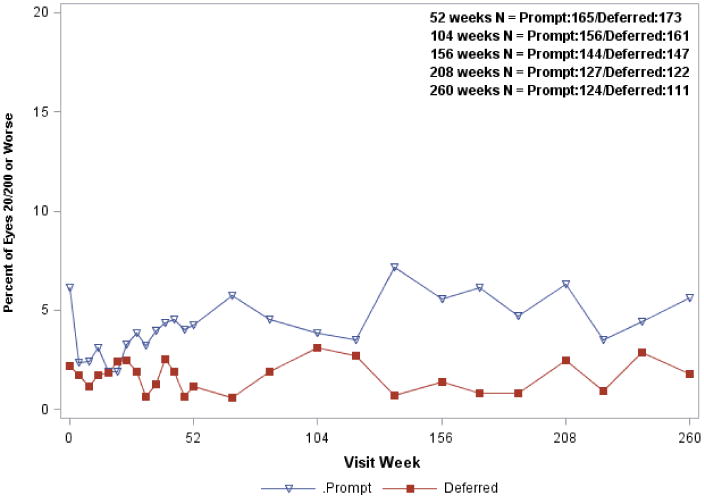

Figure 1 shows the mean visual acuity change from baseline over time for all randomized study eyes in the ranibizumab groups. At the 5-year visit, the estimated mean difference in the visual acuity letter score change from baseline using longitudinal analyses was 2.6 letters less in the ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment group compared with the ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment group (7.2 versus 9.8 letters, 95% confidence interval (CI) on the difference = 5.5 letters worse to 0.4 letters better, P = 0.09 from the model adjusting for baseline visual acuity, and P = 0.15 adjusted for all potential confounders) (Table 3, available at http://aaojournal.org). The percentage of eyes with at least a 10- or at least a 15-letter improvement in visual acuity from baseline (Table 4) was greater in the ranibizumab plus deferred laser treatment compared with the ranibizumab plus prompt laser group (58% vs. 46%, P = 0.04 for at least a 10-letter improvement; 38% vs. 27%, P = 0.03 for at least a 15-letter improvement). A visual acuity loss of ≥10 letters at 5 years was 9% and 8% in the prompt and deferred laser treatment groups, respectively. Results appeared similar when the analysis was limited to the 235 eyes with 5-year follow-up data (Figure 2, available at http://aaojournal.org). The differences in favor of the deferred laser treatment group were greater among the subgroup of eyes with worse visual acuity at baseline (approximate Snellen equivalent less than 20/50) (P<0.001 at 5 years and P = 0.004 from longitudinal model, Figure 3; Table 5, available at http://aaojournal.org). The proportion of eyes with visual acuity 20/40 or better at every visit is shown in Figure 4 available at http://aaojournal.org, and the proportion of eyes with visual acuity 20/200 or worse is shown in Figure 5 available at http://aaojournal.org.

Figure 1. Mean Change in Visual Acuity at Follow-up Visits.

Open triangle (Prompt) = Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment; closed square (Deferred) = Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment. Visual acuity change truncated to ±30 letters. Results were similar without truncation (data not shown).

Difference in mean change in visual acuity at 5 years from longitudinal model: P value adjusted for baseline visual acuity = 0.09; P value adjusted for baseline visual acuity and other potential confounders = 0.15.

Table 3. Longitudinal Analysis on Visual Acuity Change from Baseline.

| 172 weeks | 188 weeks | 208 weeks (4 Years) | 224 weeks | 240 weeks | 260 weeks (5 Years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment | N | 130 | 127 | 127 | 114 | 113 | 124 |

| Estimated mean visual acuity change from baseline** | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.2 | |

| Ranibizumab + Deferred laser treatment | N | 127 | 120 | 122 | 111 | 105 | 111 |

| Estimated mean visual acuity change from baseline ** | 9.2 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 9.8 | |

| Difference (95% CI): Prompt vs. Deferred | -1.7 (-3.8, +0.4) | -1.6 (-3.6, +0.4) | -2.1 (-4.4, +0.3) | -2.2 (-4.7, +0.3) | -2.4 (-5.1, +0.3) | -2.6 (-5.5, +0.4) | |

| P-value | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09*** |

CI = confidence interval

Visual acuity change truncated to ±30 letters.

The model estimated changes from baseline starting with week 16 through 5 years, which coincide with completion of four mandatory monthly injections in each group; Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment group: mean visual acuity change is decreasing by 0.1 letters per year; Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment group: mean visual acuity change is increasing by 0.4 letters per year. Adjusted for baseline visual acuity

P = 0.15 adjusted for baseline visual acuity and additional potential confounders (baseline central subfield thickness, age, prior panretinal photocoagulation, lens status, diabetic retinopathy severity level)

Table 4. Visual Acuity Outcomes from Baseline to the Five Year Visit.

| Ranibizumab + Prompt Laser treatment N = 124 | Ranibizumab + Deferred Laser treatment N = 111 | |

|---|---|---|

| Visual acuity letter score at 5 yr visit (approximate Snellen equivalent) | ||

| Median (25th and 75th percentile) | 76 (65, 82) | 77 (68, 82) |

| ≥79 (≥20/25) | 53 (43%) | 44 (40%) |

| 78-69 (20/32 to 20/40) | 32 (26%) | 39 (35%) |

| 68-59 (20/50 to 20/63) | 18 (15%) | 14 (13%) |

| 58-49 (20/80 to 20/100) | 9 (7%) | 9 (8%) |

| 48-39 (20/125 to 20/160) | 5 (4%) | 3 (3%) |

| ≤38 (≤20/200) | 7 (6%) | 2 (2%) |

| Change in visual acuity (letter score) | ||

| Mean ± SD | +8 ± 13 | +10 ± 13 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | +9 (+3, +16) | +12 (+4, +19) |

| Difference in mean change‡, deferred vs prompt (95% CI) [P value] | +2.6 (-0.4, +5.5) [P = 0.09] | |

| Distribution of change, no. (%) | ||

| ≥30 letter score improvement | 4 (3%) | 10 (9%) |

| 29-25 letter score improvement | 5 (4%) | 3 (3%) |

| 25-20 letter score improvement | 15 (12%) | 11 (10%) |

| 19-15 letter score improvement | 10 (8%) | 18 (16%) |

| 14-10 letter score improvement | 24 (19%) | 22 (20%) |

| 9-5 letter score improvement | 24 (19%) | 18 (16%) |

| Same ±4 letters | 28 (23%) | 13 (12%) |

| 5-9 letters worse | 3 (2%) | 7 (6%) |

| 10-14 letters worse | 4 (3%) | 3 (3%) |

| ≥15 letters worse | 7 (6%) | 6 (5%) |

| Difference in proportion with ≥10 letter improvement, deferred vs prompt (95% CI) | +11% (-2%, +24%) | |

| Relative risk (95% CI) P value | 1.27 (1.01, 1.60) P = 0.04 | |

| Difference in proportion with ≥10 letter worsening, deferred vs prompt (95% CI) | -1% (-8%, +6%) | |

| Relative risk (95% CI) P value | 0.91 (0.40, 2.10) P = 0.83 | |

| Difference in proportion with ≥15 letter improvement, deferred vs prompt (95% CI) | +10% (-2%, +22%) | |

| Relative risk (95% CI) P value | 1.47 (1.04, 2.09) P = 0.03 | |

| Difference in proportion with ≥15 letter worsening, deferred vs prompt (95% CI) | 0% (-6%, +6%) | |

| Relative risk (95% CI) P value | 0.96 (0.34, 2.72) P = 0.94 | |

SD = standard deviation; CI = confidence interval.

Visual acuity change truncated to ±30 letters.

Based on longitudinal model, adjusted for baseline visual acuity.

Figure 2. Mean Change in Visual Acuity at Follow-up Visits Limited to the Cohort that Completed the Five-year Visit.

Open triangle (Prompt) = Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment; closed square (Deferred = Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment. Visual acuity change truncated to ±30 letters.

Difference in mean change in visual acuity at 5 years from longitudinal model: P value adjusted for baseline visual acuity = 0.12; P value adjusted for baseline visual acuity and other potential confounders = 0.36.

Figure 3. Mean Change in Visual Acuity at Follow-up Visits Stratified by Baseline Visual Acuity Subgroup.

Open triangle (Prompt) = Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment; closed square (Deferred) = Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment. Visual acuity change truncated to ±30 letters. P value for interaction of treatment group with baseline visual acuity over 5 years from longitudinal model =0.004.

Table 5. Visual Acuity at the Five-Year Visit within Selected Subgroups.

| Treatment Group | VA Loss ≥10 Letters | VA Gain ≥10 Letters | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment | Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment | % | % | ||||||

| Change in VA from Baseline | Change in VA from Baseline | Treatment Group | Treatment Group | ||||||

| N | Mean | N | Mean | Pi** | Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment | Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment | Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment | Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.19 | ||||||||

| Black | 19 | 8 | 18 | 3 | 11% | 22% | 47% | 39% | |

| Other | 13 | 6 | 14 | 12 | 23% | 14% | 62% | 71% | |

| White | 92 | 8 | 79 | 11 | 7% | 4% | 45% | 59% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Prior PRP | 0.008† | ||||||||

| No | 83 | 7 | 88 | 11 | 12% | 6% | 43% | 60% | |

| Yes | 41 | 10 | 23 | 5 | 2% | 17% | 54% | 48% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Prior Treatment for DME | 0.90 | ||||||||

| No | 43 | 8 | 41 | 10 | 12% | 10% | 44% | 56% | |

| Yes | 81 | 8 | 70 | 10 | 7% | 7% | 48% | 59% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Prior Laser Treatment for DME | 0.80 | ||||||||

| No | 52 | 8 | 47 | 10 | 13% | 9% | 48% | 55% | |

| Yes | 72 | 8 | 64 | 10 | 6% | 8% | 46% | 59% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Baseline VA Letter Score | <0.001‡ | ||||||||

| ≤65 (∼Worse than 20/50) | 63 | 10 | 52 | 17 | 11% | 0% | 62% | 83% | |

| ≥66 (∼20/50 or better) | 61 | 5 | 59 | 4 | 7% | 15% | 31% | 36% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Baseline CSF thickness (μm)* | 0.10 | ||||||||

| <400 | 69 | 7 | 60 | 7 | 9% | 10% | 42% | 47% | |

| ≥400 | 55 | 10 | 51 | 13 | 9% | 6% | 53% | 71% | |

|

| |||||||||

| Baseline Photograph DR Severity* | 0.45 | ||||||||

| Mod Severe NPDR or better | 69 | 8 | 71 | 10 | 6% | 6% | 43% | 58% | |

| Severe NPDR or worse | 53 | 8 | 33 | 8 | 13% | 12% | 51% | 58% | |

|

| |||||||||

| DME Type on clinical exam | 0.61 | ||||||||

| Typical/predominantly focal | 32 | 5 | 37 | 9 | 13% | 8% | 34% | 49% | |

| Neither focal or diffuse | 30 | 10 | 28 | 9 | 7% | 7% | 57% | 54% | |

| Typical/predominantly diffuse | 62 | 8 | 46 | 12 | 8% | 9% | 48% | 67% | |

VA = Visual acuity, std = Standard deviation, PRP = Panretinal photocoagulation, DME = Diabetic macular edema, CST = Central subfield, DR = Diabetic retinopathy, NPDR = Non-proliferative diabetic macular edema.

VA change truncated to ±30 letters

Missing (or ungradable) fundus photograph data as follows for the ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment and ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment groups, respectively: (3, 7).

P value for interaction with treatment group from simple linear regression model at 5 years, adjusting for baseline visual acuity.

P value for interaction with treatment group from longitudinal model = 0.26, adjusting for baseline visual acuity.

P value for interaction with treatment group from longitudinal model = 0.004, adjusting for baseline visual acuity, and testing continuous visual acuity in the interaction term.

Figure 4. Proportion of Eyes With Visual Acuity Letter Score ≥69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/40 or Better) at Follow-up Visits.

Open triangle (Prompt) = Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment; closed square (Deferred) = Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment.

Figure 5. Proportion of Eyes With Visual Acuity Letter Score ≤38 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/200 or Worse) at Follow-up Visits.

Open triangle (Prompt) = Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment; closed square (Deferred) = Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment.

A difference between the two ranibizumab groups in OCT outcomes could not be identified (Figure 6, Table 6, and Table 7, available at http://aaojournal.org). At the 5-year visit, the percentage of eyes with a CSF thickness ≥250 μm on time domain OCT (or using TD equivalent units) was 35% in both groups (P = 0.91). The percentage of eyes with a visual acuity letter score (approximate Snellen equivalent) of 78 or worse (20/32 or worse) and a central subfield thickness ≥250 μm was 23% and 24% in the prompt and deferred laser treatment groups, respectively (P = 0.90). Similarly, when a longitudinal analysis of change in CSF thickness from baseline was performed (Table 7), no difference between the prompt and deferred groups at 5 years was identified (-8μm difference, P = 0.48 from the model adjusting for baseline CSF thickness and visual acuity, and P = 0.53 adjusted for all potential confounders).

Figure 6. Mean Change in Optical Coherence Tomography Central Subfield Retinal Thickening at Follow-up Visits.

Open triangle (B) = Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment; closed square (C) = Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment. Difference in mean change in OCT central subfield thickness at 5 years from longitudinal model: P value adjusted for baseline CSF thickness and visual acuity = 0.48; P value adjusted for baseline CSF thickness and visual acuity and other potential confounders = 0.53.

Table 6. Change in Retinal Thickness from Baseline to Five Year Study Visit.

| Ranibizumab + Prompt Laser treatment N = 124 | Ranibizumab + Deferred Laser treatment N = 111 | |

|---|---|---|

| OCT*** Central Subfield Thickness | ||

|

| ||

| Thickness (μm) at 5-year visit | ||

| Mean ± SD | 239 ± 90 | 256 ± 110 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 217 (182, 262) | 227 (193, 290) |

| Change from baseline (μm) † | ||

| Mean ± SD | -167 ± 168 | -165 ± 165 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | -152 (-256, -65) | -160 (-245, -54) |

| Difference in mean change*, deferred vs prompt (95% CI) [P value] | --- | -8 (-30, +15) [P = 0.48] |

| Thickness <250 with at least a 25 μm decrease from baseline, no. (%) | 75 (64%) | 69 (63%) |

| Relative risk (95% CI) [P value] | --- | 0.98 (0.81, 1.20) P = 0.86 |

|

| ||

| OCT Retinal Volume | ||

|

| ||

| Total volume (mm3) at 5-year visit | ||

| Mean ± SD | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 7.2 ± 1.4 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 6.9 (6.4, 7.4) | 6.9 (6.5, 7.6) |

| Change from baseline (mm3) ‡ | ||

| Mean±SD | -1.7 ± 1.3 | -1.9 ± 2.1 |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | -1.7 (-2.5, -0.7) | -1.8 (-2.8, -0.6) |

| Difference in mean change*, deferred vs prompt (95% CI) [P value] | --- | -0.01 (-0.37, +0.34) P = 0.94 |

OCT = optical coherence tomography; SD = standard deviation; CI = confidence interval.

86 and 77 5-year visit scans in the prompt and deferred group respectively were spectral domain OCT and thus converted to Stratus equivalent values.

Missing (or ungradable) data as follows for the ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment and ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment, respectively: 6 and 1

Based on longitudinal model, adjusted for baseline visual acuity and baseline central subfield thickness for OCT central subfield thickness change and baseline visual acuity and baseline volume for OCT volume change.

Missing (or ungradable) data as follows for the ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment and ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment, respectively: 59 and 37.

Table 7. Longitudinal Analysis of Optical Coherence Tomography Central Subfield Thickness Changes from Baseline.

| 172 weeks | 188 weeks | 208 weeks | 224 weeks | 240 weeks | 260 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment | N | 126 | 124 | 126 | 111 | 108 | 118 |

| Estimated mean change in OCT CSF thickness from baseline* | -158 | -156 | -163 | -165 | -167 | -170 | |

| Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment | N | 123 | 119 | 118 | 107 | 102 | 110 |

| Estimated mean change in OCT CSF thickness from baseline* | -148 | -147 | -154 | -156 | -159 | -162 | |

| Difference (95% CI): Prompt vs. Deferred* | -9 (-25, +6) | -9 (-24, +5) | -9 (-27, +9) | -9 (-28, +11) | -8 (-29, +12) | -8 (-30, +14) | |

| P-value | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.48*** |

OCT = Optical coherence tomography, CSF = Central subfield, CI = Confidence interval.

The model estimated changes from baseline starting with week 16 through 5 years, which coincides with completion of four mandatory monthly injections in each group; Ranibizumab + prompt laser treatment group: mean CSF thickness change is decreasing by 7 μm per year; Ranibizumab + deferred laser treatment group: mean CSF thickness change is decreasing by 8 μm per year. Adjusted for baseline VA and baseline CSF

P = 0.53 adjusted for baseline CSF thickness, visual acuity and other potential confounders (baseline age, prior panretinal photocoagulation, lens status, diabetic retinopathy severity level)

One (1%) of 187 eyes among 2557 injections (0.04% per injection) and two (1%) of 188 eyes among 3176 injections (0.06% per injection) in the ranibizumab plus prompt and ranibizumab plus deferred laser treatment groups, respectively, experienced injection-related endophthalmitis. Systemic safety will be reported in a separate paper, comparing all four randomized treatment groups evaluated in the trial.

Discussion

When the DRCR.net reported the 1-year study results demonstrating an improvement in mean visual acuity in eyes with vision loss from DME involving the foveal center that had been treated with ranibizumab, the question remained whether this improvement could be safely sustained over time and if so, how many treatments were given within the DRCR.net protocol. Further more, the one-year results did not suggest that prompt laser treatment added value when initiating ranibizumab compared with delayed laser treatment. To assess whether there was a long-term value from the combination of initial focal/grid laser and intravitreous ranibizumab injections for DME, the study was extended from three to five years for participants in the ranibizumab treatment arms. The five-year results showed that the 1- to 3-year findings3 were sustained; in particular, the following specific findings were noted after initiating intravitreous ranibizumab: (1) the average visual acuity gain at one year was maintained to five years concomitant with a progressively diminishing number of treatments and visits (2) adding focal/grid laser treatment at the initiation of intravitreous ranibizumab was no better than deferring the addition of laser treatment for at least 24 weeks; (3) deferring focal/grid laser may be associated with a greater chance of relatively larger improvements in visual acuity through five years compared with adding focal/grid laser when initiating intravitreous ranibizumab, especially among those eyes with worse visual acuity at baseline; (4) over half of the eyes assigned to deferral of focal/grid laser never received laser from initiation of intravitreous ranibizumab through 5 years; (5) eyes assigned to prompt laser needed fewer intravitreous injections (a median difference of 4 injections between groups); (6) few eyes in the prompt or deferred group had a substantial loss in visual acuity from DME during the 5 years of the study; and (7) approximately one-third of the eyes in both the prompt and deferred laser treatment groups had CSF thickening at 5 years, although some had visual acuities better than 20/32 despite the edema.

As suggested in the 3-year report, the observed difference in visual acuity which favored the ranibizumab plus deferred laser group may be related to a greater number of ranibizumab injections during follow-up in the deferred laser group. Alternatively, or in addition, the observed difference in visual acuity may be related to a potentially destructive effect of the macular laser treatment required of all eyes at baseline assigned to ranibizumab combined with prompt focal/grid laser group but given to fewer than half of the ranibizumab combined with deferred focal/grid laser group. While it is difficult to compare these results to those from other clinical trials evaluating ranibizumab for DME, particularly because of different retreatment protocols and different baseline visual acuity distributions, similar results to this DRCR.net trial were noted in RESTORE through one year.6 In the RESTORE trial the average visual acuity at baseline (approximate Snellen equivalent) was 20/50 and there was a trend for eyes assigned to ranibizumab alone to have a better level of visual acuity at 1 year than eyes assigned to ranibizumab plus macular laser.6

Some of the strengths of this study include a study design involving randomization of the two treatment groups at baseline to try to minimize confounding and bias, and masking of the visual acuity examiners and OCT technicians. In addition, to our knowledge, there are no other studies with 5-year data collected prospectively from eyes receiving anti-VEGF therapy for center-involved DME with vision impairment.

Limitations include participants without complete follow-up such that the 5-year data is absent on about a quarter (excluding deaths) of all randomized eyes mostly due to participants who chose not to continue in the extension phase of the study. The longitudinal models use the available data from all randomized eyes to adjust estimates for vision and OCT outcomes over the course of 5 years, but it is not possible to know whether incomplete data were related to unobserved factors that could have affected the results in either direction. There were also some differences between participants who did and did not have a 5-year visit within both the prompt and deferred laser treatment groups, as well as some differences between those who completed the 5-year visit in the prompt versus deferred laser treatment groups. These potential confounding variables were included in the adjusted longitudinal models to try to adjust for the observed differences.

The differences in visual acuity outcomes between the prompt and deferred laser treatment groups may be real, in particular for eyes with worse baseline visual acuity, but must be tempered with the recognition that deferral of laser may require more injections over 5 years to achieve the results seen in this report, and thus may entail greater costs (although a cost effectiveness analysis of these two treatment groups is beyond the scope of this study). Also, these results only may apply to patients similar to those enrolled in this trial and those that are followed with the same re-treatment criteria. Individual patients may benefit from other strategies based on individual decisions by the patient and physician during the management of patients who present with DME involving the center of the macula causing vision impairment. Nevertheless, this is the first report, to our knowledge, to provide 5-year data which suggest that most eyes initiating ranibizumasb with prompt or deferred laser can maintain vision gains obtained by the first year visit through 5 years with minimal administration of treatment after 3 years.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported through cooperative agreements from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services EY14231, EY14229, EY18817, EY023207.

The funding organization (National Institutes of Health) participated in oversight of the conduct of the study and review of the manuscript but not directly in the design or conduct of the study, nor in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation of the manuscript. Genentech provided the ranibizumab for the study. In addition, Genentech provided funds to DRCR.net to defray the study's clinical site costs. As described in the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) Industry Collaboration Guidelines (available at www.drcr.net), the DRCR.net had complete control over the design of the protocol, ownership of the data, and all editorial content of presentations and publications related to the protocol.

Footnotes

A published list of the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network investigators and staff participating in this protocol can be found in Ophthalmology 2010;117:1064-1077.e35 with a current list available at www.drcr.net

Financial Disclosures: A complete list of all DRCR.net investigator financial disclosures can be found at www.drcr.net.

Financial conflicts of interest: Dr. Bressler is principal investigator of grants at The Johns Hopkins University sponsored by the Bayer; Genentech, Inc, Novartis Pharma AG, Regeneron, and The Emmes Corporation through the Office of Research Administration of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and has a contract agreement from the American Medical Association to the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1064–77 e35. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elman MJ, Bressler NM, Qin H, et al. Expanded 2-year follow-up of ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:609–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elman MJ, Qin H, Aiello LP, et al. Intravitreal ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema with prompt versus deferred laser treatment: three-year randomized trial results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2312–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Springer Series in Statistics. New York: Springer; 2000. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diabetic Retinopathy Clincical Research Network. Reproducibility of spectral domain optical coherence tomography retinal thickness measurements and conversions to equivalent time domain metrics in diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1698. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell P, Bandello F, Schmidt-Erfurth U, et al. The RESTORE study ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:615–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]