Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to investigate alcohol use, sexual risk behavior, and trichomoniasis in a sample of low-income, largely minority women patients at a publicly-funded STD clinic in the United States.

Methods

Baseline data, collected as part of a clinical trial, were used. Patients (688 women, 46% of the overall sample) completed an audio-computer assisted self-interview that included questions about their alcohol use and sexual behaviors. Trichomoniasis was determined from vaginal swab specimens obtained during a standard clinical exam.

Results

Women (n = 580; 18 to 56 years of age; 64% Black) who reported that they had consumed alcohol at least once in the past year were included in the analyses. Of the 580 women, 157 women were diagnosed with a STD and 80 tested positive for trichomoniasis. Trichomoniasis was associated with having multiple sexual partners (OR = 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.17) but not with the number or proportion of unprotected sex events (Ps >.05) in the past 3 months. Quantity of alcohol use (drinks per drinking day, drinks per week, and peak consumption) moderated the association between number of sexual partners and trichomoniasis.

Conclusions

Number of sexual partners predicted the probability of trichomoniasis when women reported drinking larger quantities of alcohol. Because having multiple sexual partners increases the risk for STD transmission, interventions designed for at-risk women should address the quantity of alcohol consumed as well as partner reduction to reduce risk for trichomoniasis.

Keywords: STD, trichomonas vaginalis, alcohol, sexual risk behavior, women

INTRODUCTION

Trichomoniasis is the most common curable sexually transmitted disease (STD) among women in the U.S.[1] Prevalence of trichomoniasis is 3% among reproductive-age women, more than the prevalence of chlamydia and gonorrhea combined.[2, 3] But, unlike chlamydia and gonorrhea, trichomoniasis is not a reportable STD and therefore lacks the public health resources and attention required to control or prevent infection.[4] Epidemiological evidence suggests that infection with trichomoniasis is associated with high-risk sexual behavior (e.g., [2]). Consequences of trichomoniasis include vaginal irritation and discharge, reduced sexual pleasure, and reproductive health complications as well as increased risk of HIV and other STDs.[1, 4] The direct medical costs associated with new infections approaches $34 million U.S. dollars annually;[5] with trichomoniasis-attributable HIV costs estimated at $167 million annually.[6]

A prominent risk factor in the transmission of STDs is alcohol use. Alcohol may increase an individual’s risk by impairing sexual decision-making and disturbing the immune system.[7, 8] Behaviorally, alcohol use has been associated with multiple partners and unprotected sex,[7, 9]. Alcohol use has been associated with STD transmission, in general; that is, a systematic review of 42 studies found an overall association between alcohol and any STD transmission.[8] The relation between alcohol use and trichomoniasis, in particular, is less clear. Only a few investigations have focused on trichomoniasis as a separate outcome, and these few have yielded mixed results. Thus, the relation between alcohol, sexual risk behavior, and trichomoniasis remains poorly understood.

Studies on the role of alcohol use in the transmission of trichomoniasis are clouded due to methodological limitations, including the use of global rather than specific measures of alcohol use, neglecting to study interaction effects, and inclusion of non-alcohol users in data analyses. The current study addresses these limitations by restricting our sample to alcohol users (i.e., women who drank at least once in the past year), using measures of quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption, and employing sophisticated statistical methods that allow us to test for interactions. These methods supported the testing of three hypotheses.:

Because prior research indicates that trichomoniasis is associated with multiple partners and unprotected sex.[10, 11], we hypothesized that women who engage in high-risk sexual behaviors (i.e., sex with multiple partners, unprotected sex) would more likely be diagnosed with trichomoniasis.

Given the association between alcohol and risky sex, we expected that greater quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption would be related to increased sexual risk behaviors.

Most innovatively, we predicted that alcohol would moderate the association between high risk sexual behaviors and trichomoniasis; that is, we expected the risky sex-trichomoniasis relation would be stronger when women reported greater quantity and more frequency of alcohol use.

Identifying behavioral risks associated with trichomoniasis will inform programs to prevent the acquisition of trichomoniasis and reduce HIV.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Baseline data from a U.S.-based randomized clinical trial (RCT) evaluating interventions to reduce sexual risk among STD clinic patients were used to test our hypotheses (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00183573).[12]

Patients were eligible to participate in the RCT if they (a) were ≥18 years of age, (b) reported sexual risk behavior during the past 90 days (e.g., vaginal or anal sex without a condom, having more than one sexual partner), and (c) agreed to be tested for HIV. Patients were excluded if they were (a) HIV+; (b) mentally impaired; (c) receiving inpatient substance abuse treatment; or (d) planning to move within the next year. Eligible patients met privately with a research assistant, were given details about the study, and provided written consent. Consenting patients (N = 1,559) completed an audio-computer assisted self-interview followed by a clinical visit that included a physical exam, collection of biologic samples for STD testing, and blood draw for HIV testing. Of the 1,559 patients who consented, 14 withdrew, 8 tested positive for HIV and were referred for more comprehensive services, and 54 were part of a pilot sample leaving 1,483 participants (46% female, 64% Black, mean age = 29 years). Participants were reimbursed $20 for completing the baseline assessment. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions.

Measures

The assessment included (1) demographics (e.g., age), (2) alcohol use, (3) sexual risk behavior, and (4) additional measures (e.g., HIV knowledge) as part of the larger study. Current STD diagnoses were obtained through clinical chart review.

Alcohol use

Current alcohol consumption was assessed by asking participants if they drank alcohol at least once in the past year. Participants then responded to open-ended questions about the quantity and frequency of their drinking in the form of standard drinks, defined as 12 oz of beer, 6 oz. of malt liquor, 4 to 5 oz. of wine, or 1 to 1.5 oz. of hard liquor (a shot),[13]. Specifically, participants were asked about the (a) number of days during a typical week (drinking days), (b) average number of drinks per drinking day (drinks per drinking day), and (c) maximum number of drinks consumed on a drinking day (peak consumption) over the past 3 months. To assess heavy episodic drinking (frequency of heavy drinking), women were asked (d) how many times, in the past 3 months, they consumed 4 or more drinks on one occasion.[14] The number of drinks consumed per drinking week (drinks per week) was then calculated by multiplying responses from two items: drinking days and drinks per drinking day.

Sexual risk behavior

Participants responded to these questions about their sexual behavior in the past 3 months: (a) number of partners and (b) number of events with or without a condom. Condom use was assessed by asking participants how often they had vaginal [anal] sex (a) with a condom or (b) without a condom. Responses were used to determine the number of unprotected sex events (number of episodes of unprotected vaginal and anal sex) and the proportion of unprotected sexual events (number of unprotected vaginal and anal sex events divided by the total number of vaginal and anal sex events).

STDs

Medical records were reviewed (with patient consent) to determine prevalent STDs at baseline (1 = yes, 0 = no). Trichomoniasis was determined using a wet mount from a vaginal swab following CDC protocols. This rapid trichomoniasis test provides results within 10 minutes and is 60–70% accurate.[15]. Chlamydia infections were determined using nucleic acid amplification testing of cervical specimens, gonorrhea infections were diagnosed using culture methodology, and bacterial vaginosis was diagnosed using Amsel’s criteria.[16]

Data Management and Analysis

All count variables (alcohol, sexual risk behaviors) were examined for outliers; responses ≥ 3 times the interquartile range from the 75th percentile were truncated to three times the interquartile range plus one.[17] Variables that were non-normally distributed (i.e., number partners, unprotected sex events) were transformed using a natural logarithmic transformation to approximate normality and facilitate statistical analysis. Summary statistics (means, frequencies) described sample characteristics, alcohol and sexual behavior, and STDs. Differences between women who were and were not diagnosed with trichomoniasis were examined using logistic regression. Pearson correlations were calculated to assess the association between alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors.

Logistic regression analyses tested our hypothesis that alcohol moderated the association between sexual risk behaviors and trichomoniasis. Specifically, trichomoniasis (1 = yes, 0 = no) was predicted from sexual risk behaviors (mean centered), alcohol use (mean centered), and the interaction between sexual risk behaviors and alcohol (sexual risk behavior × alcohol use). Separate models were used to evaluate whether quantity (drinks per drinking day, drinks per week, peak consumption) or frequency (drinking days, heavy drinking) of alcohol interacted with sexual risk behaviors (number of partners, number or percent of unprotected sex). Hayes and Matthes’ macro (MODPROBE) estimated the logistic regression models.[18] Demographic variables that differed significantly by trichomoniasis diagnosis were included in the models as covariates. Plotting values, generated using MODPROBE, were used to graph significant two-way interactions illustrating the probability of trichomoniasis when sexual risk behaviors and alcohol use were set to low, medium, and high values.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Sample

Analyses were restricted to the 580 women (out of 688 women) who reported consuming alcohol in the past year. Most of these women were single (93%) and identified as Black (64%) with an average age of 28 years (18 to 56 years). Women who had children (58%) reported an average of 2 children each. Sixty-two percent had a high school education or lower; 65% had an income of less than $15,000 per year. Women reported drinking more than twice per week with an average of 7 (SD = 9) drinks per week. The maximum amount women consumed on a drinking day averaged 4 drinks (SD = 4); women reported heavy episodic alcohol consumption a mean of 3 times (SD = 5). On average, women reported having 3 sexual partners (SD = 3), and 16 events of unprotected sex (SD = 20) with 68% of events unprotected (SD = 32).

Prevalence and Correlates of T. Vaginalis

Of the 580 women in the sample, 14% (n = 80) were diagnosed with trichomoniasis. Differences between women who were and were not diagnosed with trichomoniasis are presented in Table 1. There were no differences in education, marital status, or number of children. Compared to uninfected women, women infected with trichomoniasis were older, more likely to be Black, and more likely to report earning less than $15,000 per year. Therefore, we controlled for age, race, and income in our models.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Alcohol-Using Women Attending an STD Clinic by T. Vaginalis Diagnosis

|

T. Vaginalis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Yes | No | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Sample Characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 28 (9) | 32 (10) | 28 (9) | 1.05 | 1.02 – 1.07 | <.001 |

| Race (% Black) | 64 | 81 | 61 | 2.75 | 1.53 – 4.95 | .001 |

| Education (% high school or less) | 62 | 69 | 60 | 1.44 | 0.87 – 2.39 | .156 |

| Income (% <$15,000/year) (n = 579) | 65 | 78 | 63 | 2.14 | 1.22 – 3.77 | .008 |

| Marital status (% unmarried) | 93 | 89 | 94 | 0.52 | 0.24 – 1.14 | .103 |

| Children (n = 335) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 1.10 | 0.97 – 1.24 | .136 |

| Alcohol Use | ||||||

| Drinking days (n = 579) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1.04 | 0.91 – 1.19 | .549 |

| Drinks per drinking day (n = 579) | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 3 (3) | 0.95 | 0.85 – 1.05 | .280 |

| Drinks per week (n = 579) | 7 (9) | 7 (11) | 7 (9) | 1.00 | 0.98 – 1.03 | .758 |

| Frequency of heavy drinking (n = 578) | 3 (5) | 3 (4) | 3 (5) | 0.99 | 0.95 – 1.04 | .819 |

| Maximum drinks/drinking day (n = 579) | 4 (4) | 4 (3) | 4 (4) | 0.96 | 0.90 – 1.03 | .295 |

| Sexual Behaviors | ||||||

| Sexual partners (count) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 1.09 | 1.01 – 1.17 | .036 |

| Unprotected sex (count) (n = 577) | 16 (20) | 16 (19) | 17 (21) | 1.00 | 0.99 – 1.01 | .706 |

| Unprotected sex (%) (n = 577) | 68 (32) | 66 (32) | 68 (32) | 0.85 | 0.41 – 1.75 | .652 |

| STDs and Other Infections | ||||||

| Chlamydia (%) | 10 | 9 | 10 | 0.88 | 0.38 – 2.02 | .768 |

| Gonorrhea (%) | 8 | 10 | 7 | 1.43 | 0.64 – 3.20 | .382 |

| Bacterial Vaginosis (%) | 56 | 70 | 53 | 2.04 | 1.22 – 3.39 | .006 |

OR, odd ratio. CI, confidence interval. Sample size is 580 unless otherwise noted.

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1: Women diagnosed with trichomoniasis will report more high risk sexual behavior than those without trichomoniasis

Women with trichomoniasis reported significantly more sexual partners in the past 3 months than those not diagnosed with trichomoniasis (M = 3.38 vs. 2.70 partners, respectively). Number and proportion of unprotected events were not associated with trichomoniasis.

Hypothesis 2: Greater quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption will be associated with increased sexual risk behaviors

Alcohol was positively correlated with sexual partners (Ps ≤.01); that is, greater quantity (i.e., drinks per drinking day, drinks per week, peak consumption) and frequency (i.e., drinking days, heavy episodic drinking) of alcohol consumption was associated with more sexual partners (correlations ranged from 0.11 to 0.20; Table 2). Alcohol was not associated with the number or proportion of unprotected sex events with one exception: heavy episodic drinking was negatively associated with the proportion of unprotected sex events (r = −.09, P = .02).

Table 2.

Correlations between sexual partners and alcohol consumption.

| Sexual Partners |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | Fisher’s z-score | 95% CI | |

| Quantity | ||||

| Drinks per drinking day | .116 | .005 | .116 | 0.03, 0.20 |

| Drinks per week | .197 | <.001 | .198 | 0.12, 0.28 |

| Peak Consumption | .108 | .010 | .108 | 0.03, 0.19 |

| Frequency | ||||

| Drinking days | .180 | <.001 | .180 | 0.10, 0.26 |

| Heavy episodic drinking | .113 | .006 | .113 | 0.03, 0.19 |

Hypothesis 3: Alcohol consumption will moderate the association between high risk sexual behaviors and trichomoniasis

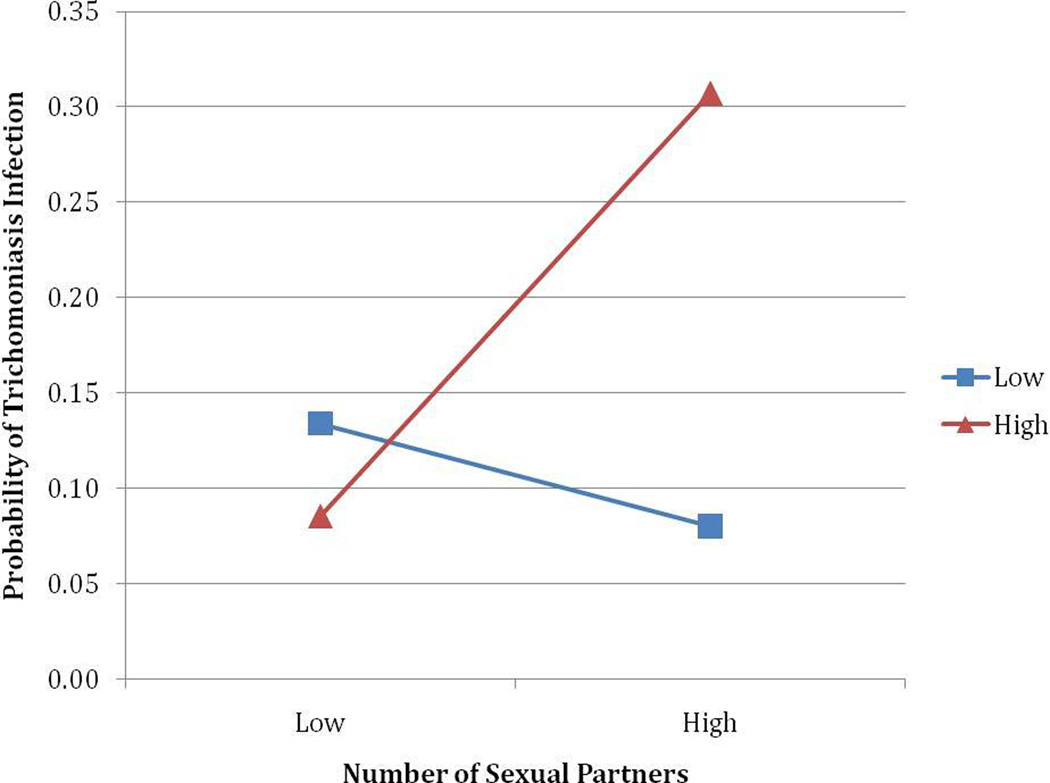

Because trichomoniasis was not associated unprotected sex, we focused our analyses on the number of sexual partners.1 The association between sexual partners and trichomoniasis infection was moderated by the quantity, but not the frequency, of alcohol consumption. The logistic regression models showed a statistically significant interaction for number of sexual partners and drinks per drinking day (OR = 1.03, P = .04), drinks per drinking week (OR = 1.01, P = .04), and peak consumption (OR = 1.02, P = .02) but not drinking days (OR = 1.03, P = .10) or heavy episodic drinking (OR = 1.01, P = .39). The models for drinks per drinking day (Χ2 [6] = 35.94, P <.001), drinks per drinking week (Χ2 [6] = 35.27, P <.001), and peak consumption (Χ2 [6] = 35.84, P <.001) fit better than the constant only models. Probing the significant interactions at low, moderate, and high levels of alcohol use show that the alcohol-trichomoniasis association is significant when consumption is high, with greater quantities of alcohol associated with trichomoniasis (Ps < .05). Probing with the Johnson-Neyman technique (i.e., a mathematical method of determining the precise point along the continuum of the moderator when the predictor becomes statistically significant[18]), showed that number of sexual partners is associated with trichomoniasis when the number of drinks per drinking day are ≥ 4.22 drinks, the number of drinks per week are ≥ 15.72, and peak consumption on a single day is ≥ 6.24 drinks (Ps <.05). Figures 1 illustrates the probability of trichomoniasis from the interaction between number of sexual partners and quantity of alcohol consumed (i.e., drinks per drinking day [A], drinks per week [B], and peak consumption [C]).

Figure 1.

The predicted probability of trichomoniasis from the interaction of number of sexual partners and drinks per drinking day (A), drinks per week (B), and peak consumption (C).

DISCUSSION

Alcohol has been implicated as an important factor in the acquisition of STDs.[7, 8] Women attending STD clinics often report alcohol use, which may exacerbate their risk for STDs.[19, 20] In this study, we examined whether alcohol use moderates the association between sexual risk behavior and trichomoniasis in a sample of low-income, largely minority women at a publicly-funded U.S. STD clinic.

Three important findings were obtained. First, we found that risky sexual behavior in the past 3 months was associated with trichomoniasis. The association between sexual behavior and trichomoniasis was observed only for multiple partners and not for the frequency (number or proportion) of unprotected sexual events. Finding that multiple partners is the more important predictor of trichomoniasis corroborates previous reports that have focused on trichomoniasis,[10] and indicates the important role of multiple partners in STD transmission.

Second, quantity and frequency of alcohol use were associated with having multiple sexual partners. Previous research on the alcohol-sexual behavior association has focused primarily on condom use;[21, 22] the current research extends this work to number of partners. Clearly, both indicators of risk are important. Our results suggest that risk reduction interventions should address alcohol use in the context of multiple partners.

Third, our results show that the quantity of alcohol, but not the frequency, moderates the association between sexual partners and trichomoniasis. That is, having more sexual partners, coupled with excessive alcohol consumption per drinking day, drinking week, and on peak occasions, was associated with greater risk for trichomoniasis. The magnitudes of the odd ratios were small but are consistent with the view that high-rates of consumption are the riskiest type of alcohol use. High levels of intoxication compromise executive function,[23] disinhibiting behaviors typically restrained by concerns about long-term consequences. [24] In addition, situational factors might contribute to risky sex via mobilization of alcohol-related expectancies supporting risk behavior.[25] Interventions to reduce sexual risk should also attend to alcohol use patterns. Fortunately, brief (i.e., one session) motivational interventions for alcohol use modification can be deployed in public health and primary care settings.[26] In addition, interventions combining STD risk and alcohol reduction have proven efficacious in reducing risky sexual behavior relative to STD risk reduction only.[27]

Women attending STD clinics are at high risk for trichomoniasis. The prevalence of trichomoniasis was nearly 5 times higher in this sample than the overall prevalence of trichomoniasis among reproductive-age women in the U.S.[2] We identified several predictors of trichomoniasis including age, ethnicity, and income. Considerable age, racial, and socio-economic status disparities exist; this study as well as prior research shows that the prevalence of trichomoniasis is higher among older (vs. younger) women, non-Hispanic blacks (vs. non-Hispanic whites), and women with low (vs. high) incomes.[2, 10] Bacterial vaginosis was also a predictor of trichomoniasis; prior research indicates that bacterial vaginosis is a common co-infection of trichomoniasis.[4] Overall, these findings suggest that interventions targeting women who use alcohol in settings where rates of sexual risk behavior may be high, such as publicly-funded STD clinics, are needed to reduce sexual risk behaviors and subsequent infections among women at greatest risk for trichomoniasis.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. As with any study conducted at a single site, our sample of low-income women patients who consumed alcohol may not be representative of all women STD clinic patients. These findings are also limited by our use of self-reports of alcohol and sexual behaviors; however, we assessed behaviors using ACASI – a reliable and valid method for assessing sensitive behaviors in STD settings.[28] Trichomoniasis was determined using a wet mount from a vaginal swab with a 60–70% accuracy; use of a nucleic acid amplification test may improve the detection of trichomoniasis. [29] Finally, our data are cross-sectional and do not support causal inferences. Longitudinal data could provide stronger evidence on whether alcohol impacts the effect of multiple partners on trichomoniasis infection.[30]

CONCLUSION

Prevalence of trichomoniasis was high among low-income, largely minority, women patients attending a publicly-funded STD clinic who consumed alcohol. More sexual partners predicted the probability of trichomoniasis when women reported greater quantity, but not increased frequency, of alcohol. Greater quantity, but not the frequency, of alcohol may elevate sexual risk due to the restriction of cognitive processing (cf. alcohol myopia model [24]). Because having multiple partners increases the risk for trichomoniasis which increases susceptibility of HIV acquisition, interventions designed for at-risk women should address the quantity of alcohol consumed to reduce sexual risk and the prevalence of trichomoniasis.

KEY MESSAGES.

Predictors of trichomoniasis include older age, African-American race, low-income, multiple sexual partners, and bacterial vaginosis.

Alcohol consumption (quantity and frequency) is associated with multiple sexual partners in women patients attending an STD clinic.

Quantity, but not frequency, of alcohol consumption moderated the association between multiple sexual partners and trichomoniasis infection.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health (R01-MH068171 to Michael P. Carey). We thank the participants, staff, and our research team.

Footnotes

Corresponding author statement: The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in STI and any other BMJPGL products and sub-licenses such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license http://group.bmj.com/products/journals/instructions-for-authors/licence-forms.

Logistic regression analyses revealed no significant interaction between any alcohol consumption measure and unprotected sex (number or proportion of events), Ps ≥.13.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

- Study concept and design: Scott-Sheldon, MP Carey

- Acquisition of data: Senn

- Analysis and interpretation of data: Scott-Sheldon, Senn, Urban, KB Carey, MP Carey

- Drafting of the manuscript: Scott-Sheldon

- Critical revision of the manuscript: Scott-Sheldon, Senn, Urban, KB Carey, MP Carey

- Statistical analysis: Scott-Sheldon

- Obtaining funding: MP Carey

- Administrative, technical, or material support: Senn, Urban

- Study supervision: MP Carey

None of the authors have any conflicts that might be interpreted as influencing the research.

Contributor Information

Lori A. J. Scott-Sheldon, Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital and Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

Theresa E. Senn, Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital and Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

Kate B. Carey, Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, and Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

Marguerite A. Urban, University of Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester, NY, USA.

Michael P. Carey, Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital, Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Trichomoniasis--CDC Fact Sheet. Secondary Trichomoniasis--CDC Fact Sheet. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/std/trichomonas/STDFact-Trichomoniasis.htm.

- 2.Sutton M, Sternberg M, Koumans EH, McQuillan G, Berman S, Markowitz L. The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(10):1319–1326. doi: 10.1086/522532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allsworth JE, Ratner JA, Peipert JF. Trichomoniasis and other sexually transmitted infections: results from the 2001–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(12):738–744. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b38a4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwebke JR, Burgess D. Trichomoniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(4):794–803. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.794-803.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chesson HW, Blandford JM, Gift TL, Tao G, Irwin KL. The estimated direct medical cost of sexually transmitted diseases among American youth, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):11–19. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.11.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesson HW, Blandford JM, Pinkerton SD. Estimates of the annual number and cost of new HIV infections among women attributable to trichomoniasis in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(9):547–551. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000137900.63660.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shuper PA, Neuman M, Kanteres F, Baliunas D, Joharchi N, Rehm J. Causal considerations on alcohol and HIV/AIDS--a systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45(2):159–166. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(3):156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. Am Psychol. 1993;48(10):1035–1045. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helms DJ, Mosure DJ, Metcalf CA, et al. Risk factors for prevalent and incident Trichomonas vaginalis among women attending three sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(5):484–488. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181644b9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtenstein B, Desmond RA, Schwebke JR. Partnership concurrency status and condom use among women diagnosed with Trichomonas vaginalis. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(5):369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carey MP, Senn TE, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA. Brief and intensive behavioral interventions to promote sexual risk reduction among STD clinic patients: results from a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):504–517. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9587-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dufour MC. What is moderate drinking? Defining "drinks" and drinking levels. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23(1):5–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, Rimm EB. A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(7):982–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74(1):14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th ed. Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(3):924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutton HE, McCaul ME, Santora PB, Erbelding EJ. The relationship between recent alcohol use and sexual behaviors: gender differences among sexually transmitted disease clinic patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(11):2008–2015. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00788.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patton R, Keaney F, Brady M. Drugs, alcohol and sexual health: opportunities to influence risk behaviour. BMC Res Notes. 2008;1:27. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leigh BC. Alcohol and condom use: a meta-analysis of event-level studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(8):476–482. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Senn TE, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA. Alcohol consumption, drug use, and condom use among STD clinic patients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(5):762–770. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giancola PR. Executive functioning: a conceptual framework for alcohol-related aggression. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8(4):576–597. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45(8):921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper ML. Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):986–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.9.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR, Levin M, Bryan AD. Randomized trial of group interventions to reduce HIV/STD risk and change theoretical mediators among detained adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(1):38–50. doi: 10.1037/a0014513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghanem KG, Hutton HE, Zenilman JM, Zimba R, Erbelding EJ. Audio computer assisted self interview and face to face interview modes in assessing response bias among STD clinic patients. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(5):421–425. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roth AM, Williams JA, Ly R, et al. Changing sexually transmitted infection screening protocol will result in improved case finding for trichomonas vaginalis among high-risk female populations. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(5):398–400. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318203e3ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL. The analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University; 2002. [Google Scholar]