Abstract

The increase of extended- spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-E) in humans and in food-producing animals is of public health concern. The latter could contribute to spreading of these bacteria or their resistance genes to humans. Several studies have reported the isolation of third generation cephalosporin resistant bacteria in livestock animals. However, the number of samples and the methodology used differ considerably between studies limiting comparability and prevalence assessment. In the present study, a total of 564 manure and dust samples were collected from 47 pig farms in Northern Germany and analysed to determine the prevalence of ESBL-E. Molecular typing and characterization of resistance genes was performed for all ESBL-E isolates. ESBL-E isolates were found in 55.3% of the farms. ESBL-Escherichia coli was found in 18.8% of the samples, ESBL-Klebsiella pneumoniae in 0.35%. The most prevalent ESBL genes among E. coli were CTX-M-1 like (68.9%), CTX-M-15 like (16%) and CTX-M-9 group (14.2%). In 20% of the latter two, also the OXA-1 like gene was found resulting in a combination of genes typical for isolates from humans. Genetic relation was found between isolates not only from the same, but also from different farms, with multilocus sequence type (ST) 10 being predominant among the E. coli isolates. In conclusion, we showed possible spread of ESBL-E between farms and the presence of resistance genes and STs previously shown to be associated with human isolates. Follow-up studies are required to monitor the extent and pathways of ESBL-E transmission between farms, animals and humans.

Introduction

In the last decade the emergence of plasmid-encoded AmpC- β-lactamase- and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae among livestock animals has raised concern that food-producing animals may contribute to zoonotic spread of these antibiotic-resistant bacteria to humans [1–4]. Indeed, persons in the general population are increasingly colonized with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-E). Recent studies in Germany demonstrated that ESBL-E carriage affects 4–6% of all humans [5–7].

Zoonotic dissemination of resistant bacteria could either result from direct transmission between livestock animals and farmers [6, 8, 9], or via the introduction of ESBL-E in the food chain [10]. Several studies have proven that European retail meat and vegetables are contaminated with ESBL-E [11–14]. Furthermore, some studies indicated similarities between Escherichia coli strains and associated resistance genes found in meat and humans [12, 15]. In addition, spread of ESBL-encoding plasmids between bacteria from human sources and food-producing animals have been reported [16–21].

The proportion of the total burden of human colonization or infection with ESBL-E linked to the livestock reservoir is still controversial, because source attribution results are difficult to interpret [5, 22]. This is mainly due to the fact that the most accurate method for tracing epidemiological pathways of ESBL-E dissemination is unclear. Differently from multidrug-resistant microorganisms following a clonal distribution pattern, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, it seems inadequate to exclude a possible link between two ESBL-E isolates if they belong to two different clonal lineages, as antibiotic-resistance genes, located on mobile genetic elements, can be transferred between clones. Furthermore, it is unknown to what extent transfer of different resistance-associated mobile genetic elements occurs at random, or if specific elements are more prone to be acquired by enterobacteria colonizing the human intestine or causing human infection.

As a consequence, molecular characterization of ESBL-E isolates from food-producing animals has become a major research topic aiming to understand zoonotic transmission as well as transmission of ESBL-E among food-producing animals. International studies among livestock animals including poultry, cattle and pigs indicate that most ESBL-E are E. coli associated to multilocus sequence typing (MLST) clonal complexes (CC) 648, 23, 10, 405, 131, 69, and 73, and that CTX-M-1 is the most frequently detected ESBL gene [2, 3]. Other ESBL or AmpC β-lactamases frequently found in livestock animals are CMY-2, TEM-52, and SHV-12 [2, 23].

Germany is one of the major European producers of pig meat. On German pig farms, occurrence of cefotaxime resistant E. coli [24] or the occurrence of ESBL/AmpC- producing E. coli has been previously reported ranging in prevalence from 43.8% in fattening pig holdings to 56.3%, if individual fattening pigs are considered [25]. Currently published investigations on molecular typing results for ESBL-E isolates from German pig farms indicate that in E. coli isolates CTX-M-1 (66.7%) is the most frequent ESBL-gene followed by CTX-M-9 (3.5%) and CTX-M-15 (3.5%) [26]. However, as recent studies have focussed on assessing resistance genes, phylogenetic groups or PFGE profiles of ESBL-associated E. coli isolates [22, 24–26], there is limited knowledge on associated clonal lineages as determined by MLST.

Here we aim to get new insights into the prevalence of ESBL/AmpC-producing bacteria in pig farms in Germany. The following specific objectives were addressed: i) to study the β-lactamase genes present in cefotaxime resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from pig holdings in North-western Germany; ii) to compare possible outbreak-associated strains between farms using repetitive-sequence-based PCR (rep-PCR); and iii.) to determine the MLST in randomly selected isolates to reveal the clonal background of the bacterial collection in a global context [27].

Materials and Methods

Farms and sample collection

A total of 47 pig farms participated to investigate the prevalence of ESBL-E in swine holdings in the German part of the Euregio (comprising the German federal states of Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW). Between February 2013 and September 2013, six dust samples (collected using Polywipe sponge swabs, Westerau, Germany) and six manure samples (collected using sterile cotton swabs) were obtained from different locations on each pig farm. Sampling was performed by veterinarians from the animal health services of the Federal Chambers for Agriculture of the states of NRW and Lower Saxony. Farms were not actively selected, but samples were derived during routine visits of the animal health services on the farms. Of each location, one dust sample (n = 282) and one manure swab (n = 282) were enriched in non-selective broth (Caso broth, Heipha, Eppelheim, Germany) and incubated for 24h at 35 +/- 1°C. Ten μl of the sample was streaked onto a chromogenic medium for the detection of ESBL-producing organisms (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

Species identification and susceptibility testing

Presumptive ESBL colonies were subcultured on blood agar. Species confirmation was done by MALDI-TOF (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen). Susceptibility testing for ESBL-E was done by VITEK 2 automated systems according to EUCAST clinical breakpoints [28].

Resistance genotyping

ESBL-E positive samples were selected for DNA extraction using the UltraClean Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio, Laboratories, Inc.) and further characterized for the presence of ESBL/AmpC genes using a DNA-array (Check-MDR CT103, Check-points, Wageningen, The Netherlands) that includes specific DNA markers to identify the presence of the ESBL genes TEM, SHV and CTX- M (subgroups belonging to the CTX-M-1 group: CTX-M- 1 like, CTX-M-15 like, CTX-M-3 like and CTX-M-32 like); and discriminates between ESBL and non-ESBL TEM and SHV variants by detecting Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) corresponding to amino acid positions 104, 164 and 238 in TEM, and 238 and 240 in SHV. It also detects pAmpC (CMY-2-like, DHA, FOX, ACC-1, ACT/MIR and CMY-1-like/MOX) and carbapenemases (KPC, OXA-48, VIM, IMP and NDM) genes [29]. Besides, the positive and negative controls included in the kit, a clinical ESBL- producing E. coli isolate was included as a positive control.

Additionally, samples positive for CTX-M-15 like or CTX-M-9 group were assessed by PCR for the presence of bla OXA-1 gene, which is not detected by the DNA-array. This gene has been previously described to be associated with the presence of CTX-M-15 in humans resulting in resistance to inhibitors [30]. The PCR amplified part of the gene (between nucleotide positions bp 54 and 321) using the following oligonucleotide primer pairs: forward (5’ TAT CTA CAG CAG CGC CAG TG 3’) [31] and reverse primer (5’ GCT GTT CCA GAT CTC CAT TC 3’), designed in this study. PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing of primers at 59°C for 1 min, and primer extension at 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final primer extension step at 72°C for 5 min. Reactions were performed in a 25-μl final volume in duplicate, with the ReadyMix Taq PCR Reaction Mix method (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC), containing 1 and 5 μl of DNA template, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM concentrations of each primer, 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase. PCR products were visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and SYBR Green staining.

Rep-PCR

Clonal relatedness among E. coli isolates was determined by the Diversilab (DL) bacterial typing system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Analysis was performed using Pearson correlation in the dedicated DL software of the manufacturer (version 3.4). Isolates with a similarity <90% were considered different and isolates with a similarity >95% were considered indistinguishable. All isolates with a similarity between 90% and 95% were judged visually.

E. coli MLST

MLST was carried out on one isolate of every cluster obtained by DL as described previously [32]. Although the exact ST cannot be inferred for all isolates belonging to the same DL cluster, it was used as a first screening to determine the presence of clinical important STs [33]. Allelic profiles and STs were assigned in accordance to the E. coli MLST website [34].

Statistical analysis

Differences in the prevalence of ESBL-E between regions were assessed by the Fisher exact test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Prism Software, Inc.).

Ethics statement

The study was performed on private land. The owner of the farm provided informed consent. No specific permissions were required for these locations (except permission of the owner). Studies did not involve endangered or protected species. Only environmental samples were included in the study.

Results

The prevalence of ESBL-E on farm level was 55.3% (26/47 positive farms) and no differences were found between the two federal states involved (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.12). Of the total manure (n = 282) and dust (n = 282) samples tested, 27.3% (n = 77) and 10.3% (n = 29) were positive for ESBL-E. coli, respectively. In addition, 0.7% (n = 2) of dust samples were positive for ESBL-Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Antibiotic susceptibility

Results on antibiotic susceptibility data for E. coli isolates are shown in Table 1. Regarding β-lactam inhibitors, 84% and 4.7% of the E. coli isolates, were ampicillin/sulbactam and piperacillin/tazobactam resistant, respectively. The two K. pneumoniae isolates found were resistant to ampicillin, ampicillin/sulbactam, cefuroxime, cefotaxime and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and intermediate to piperacillin/tazobactam and ceftazidime (data not shown). All E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates were susceptible to carbapenems.

Table 1. Antibiotic susceptibility data of 106 E. coli isolates from 47 German pig farms.

| No. of isolates (% of 106 E. coli isolates) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic | Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant |

| Ampicillin | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 106 (100) |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 7 (6.6) | 0 (0) | 89 (84) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 2 (1.9) | 99 (93.4) | 5 (4.7) |

| Cefuroxime | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 106 (100) |

| Cefotaxime | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 106 (100) |

| Ceftazidime | 69 (65.1) | 22 (20.8) | 15 (14.2) |

| Ertapenem | 106 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Imipenem | 106 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Meropenem | 106 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gentamycin | 94 (88.7) | 0 (0) | 12 (11.3) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 78 (73.6) | 0 (0) | 28 (26.4) |

| Moxifloxacin | 76 (71.7) | 2 (1.9) | 28 (26.4) |

| Tetracycline | 31 (29.2) | 0 (0) | 75 (70.8) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 38 (35.8) | 0 (0) | 68 (64.2) |

β-lactamase genes

The β-lactamase genes found in E. coli isolates are shown in Table 2.The most prevalent ESBL gene was a CTX-M-1-like gene, alone (43.4%, n = 46) or in combination with TEMnon-ESBL (25.5%, n = 27). In addition, 6 (5.7%) E. coli isolates had an OXA-1 like gene. Two E. coli isolates presented a plasmid AmpC CMY-II together with TEMnon-ESBL. One E. coli isolate only harboured TEMnon-ESBL conferring ampicillin-resistance. For this isolate the mechanism causing the observed resistance against cefotaxime remained unclear. The two K. pneumoniae isolates harboured a CTX-M-1-like and SHVnon-ESBL gene.

Table 2. Distribution and combinations of β-lactamase genes in 106 E. coli identified from 47 German pig farms.

| β-lactamase gene | No. of isolates (% of 106 E. coli isolates) |

|---|---|

| CTX-M-1 like | 46 (43.4) |

| CTX-M-1 like + TEMnon-ESBL | 27 (25.5) |

| CTX-M-15 like | 7 (6.6) |

| CTX-M-15 like + TEMnon-ESBL | 4 (3.8) |

| CTX-M-15 like + OXA-1 like | 1 (1) |

| CTX-M-15 like + TEMnon-ESBL+OXA-1 like | 3 (2.8) |

| CTX-M-9 group | 6 (5.7) |

| CTX-M-9 group + TEMnon-ESBL | 7 (6.6) |

| CTX-M-9 group + TEMnon-ESBL +OXA-1 like | 2 (1.9) |

| CMY-II + TEMnon-ESBL | 2 (1.9) |

| TEMnon-ESBL | 1 (1) |

Rep-PCR and MLST analysis

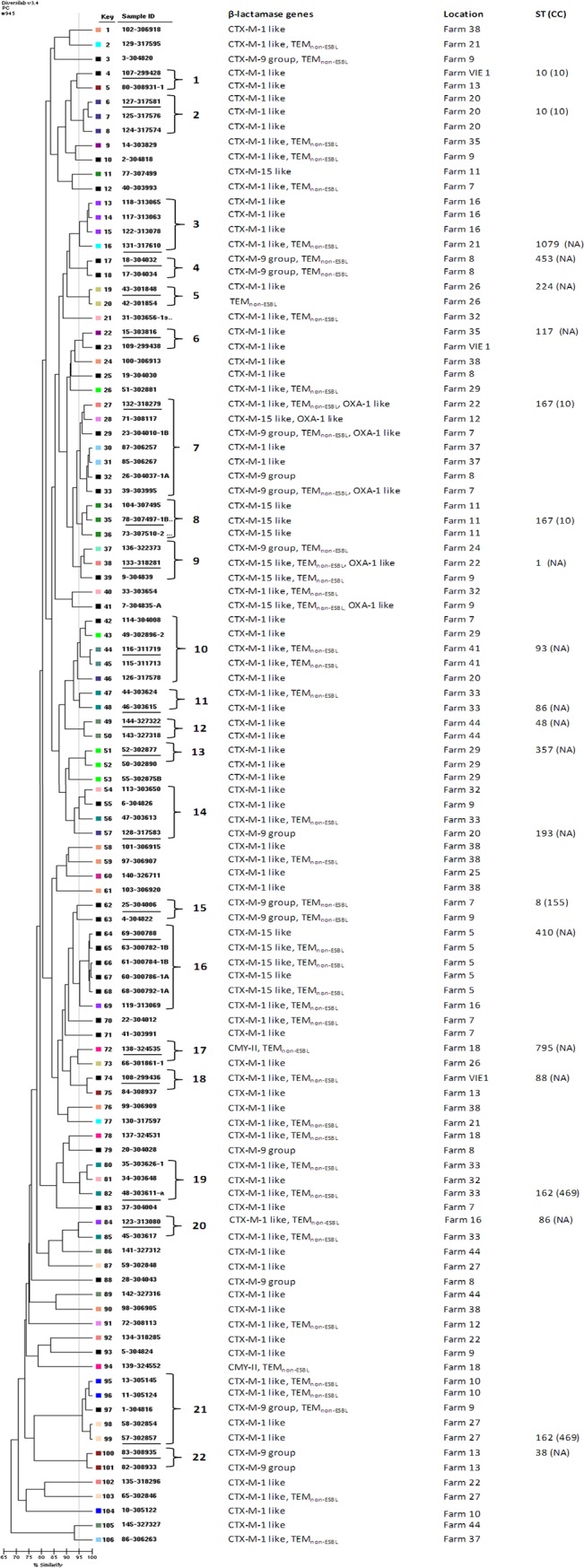

The genetic relationship among E. coli isolates is shown in the dendrogram of the Rep-PCR results (Fig 1). A total of 22 clusters formed by more than one isolate with an intracluster pairwise similarity ≥ 95%, were observed. Eight clusters were formed by isolates from the same farms, seven of them contained isolates with the same CTX-M β-lactamase gene. Fourteen clusters were formed by isolates from different farms, eight of them contained isolates with the same CTX-M β-lactamase gene (Fig 1). One isolate of every cluster was studied by MLST, most clusters showed different STs, except cluster 1 and 2 (ST10, CC10), cluster 7 and 8 (ST167, CC10), and cluster 19 and 21 (ST162, CC469) (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Dendrogram displaying the genetic relatedness of 106 E. coli isolates from pig holdings in Germany.

The dendrogram was constructed by Diversilab (DL) software. Type designations for DL clusters are given as numbers on the right. Singletons are left without designations. MLST was performed in underlined isolates and coloured boxes indicate farm numbers. The vertical grey line indicates 95% of similarity. NA, not assigned to a CC.

Discussion

An increasing number of reports on the occurrence of multiresistant bacteria in livestock animals and food items at retail are published. However, controversial information is available on the prevalence and genetic relatedness with human isolates. This is a large study into ESBL prevalence in pig holdings in Germany also including data on resistance genes and clonality. The high percentage of farms (55.3%) observed on ESBL-producing bacteria, which may even be underestimated due to the use of environmental samples and non-selective enrichment [35], indicates the importance of implementing measures to monitor and control the spread of these bacteria within the veterinary setting.

Most ESBL-positive samples contained an E. coli (98.1%). In addition, also ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (1.9%) were found that have so far not been reported in studies on livestock animals in Europe. Only one report from Korea describes five non-ESBL K. pneumoniae isolates in pigs [2, 36]. Importantly, no carbapenem resistance was found in this collection of isolates in contrast to what has been reported in two fattening pig farms positive for VIM-1 producing Salmonella in another German study [37].

The predominant ESBL gene family in this E. coli collection was CTX-M (97.2%), mostly CTX-M-1 like followed by CTX-M -15 like and CTX-M-9 group. These findings are in accordance with other studies in German pigs, although in some cases no data on specific CTX-M genes was given or only a low number of isolates was tested [25, 26, 38, 39]. Also, studies in livestock animals, including pigs, in other European countries reported CTX-M as the most common found ESBL genes [40–42]. Although CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-14 seem to be the major types in humans [2], CTX-M-1 has also been described as a prevalent ESBL gene in human source isolates [43].

Of all isolates 1.9% harboured CMY-II, a plasmid-AmpC most predominant among poultry but also described in other hosts [2]. It has been suggested that the detection of CMY-II is related with the presence of possible neighboring cattle or poultry farms in the proximity [26]. Unfortunately, no such data are available for the present study.

Remarkably, we detected one isolate harbouring only TEMnon-ESBL and no ESBL genes, which still showed cefotaxime cephalosporin resistance. The observed resistance pattern may be due to the hyperproduction of a chromosomal AmpC present in E. coli [44] or to a yet unidentified mechanism.

In this study, we confirmed investigations on the rare occurrence of OXA-1 genes in German pigs. The gene has been shown to be present in E. coli isolates from poultry meat, companion animals, cattle and waterbirds and also in Samonella spp. (mainly retail meat samples) [45–51]. In the present study, the OXA-1 like gene was studied in CTX-M-15 or CTX-M-9 producing isolates that are more linked to the human population. Indeed, CTX-M-15 and OXA-1 like have been described to be associated with the same plasmid, pC15 [52], suggesting that successful spread of some antibiotic resistance genes is due to transmission of epidemic plasmids.

Moreover, the presence of highly-related plasmids carrying ESBL and AmpC genes among E. coli isolates from different reservoirs has recently been described using whole genome sequencing. Transmission has been proven between human- and pig- but not between human- and poultry-associated isolates due to the considerable heterogeneity of the strains and despite the fact that in both cases isolates from different sources were considered to be identical based on MLST, plasmid typing or antibiotic resistance gene sequencing [12, 15,16]. Other studies support this plasmid-mediated spread of resistance genes between healthy humans and animals [53]. These studies give more insight into the possible mechanisms of ESBL dissemination and indicate that transmission of strains between different origins may be less frequent, but that the easy transfer of mobile genetic elements between bacteria of the same or even different genera is an important factor in the spread of antibiotic resistance genes. More studies including strains from different sources, animal, humans and food are needed to elucidate this pathway.

The dendrogram obtained by rep-PCR showed several clusters comprising isolates harbouring the same ESBL genes and from the same farm. This is not surprising as these animals usually share the same barn. The observation of clusters with isolates from the same farm but harbouring different ESBL genes may be due to the fact that most of these β-lactamase genes are transported in mobile genetic elements that are prone to rearrange within the genome, which facilitates easy gain or loss of genes.

Most clusters were formed by isolates from different farms (Fig 1). This may be caused by transport of animals or humans, such as farmers or veterinarians that are in close contact with the animals, or these farms may receive young animals from the same source. Unfortunately, no data are available on this. Our results are in contrast to a previous German study in swine farms, were 20 ESBL-E. coli isolates were analyzed by PFGE and appeared to be grouped by farm [26]. Interestingly, in the latter study isolates were obtained from inside and outside the pig barns indicating that bacteria may have spread into the environment of the stables due to translocation of faeces through pigs, people or vehicles [26].

The most studied and clinically important clone in ESBL-producing E. coli belongs to sequence type (ST) 131. This highly virulent clone was first described in human clinical isolates, but has also been observed in animal species, such as companion animals, poultry and food [2]. This ST was not found in the present study in the tested isolates, where CC10 (including ST10 and ST167) appeared to be the most prevalent and was associated with bla CTX-M-1, 15; group 9. CC10 has been previously described in livestock animals [2]. Moreover, ST10 E. coli isolates have been frequently identified in humans and food products associated with a diversity of ESBL genes, including TEM-52 [15, 19, 50]. In addition, isolates belonging to CC23 (bla CTX-M-15) and CC38 (bla CTX-M-9 group) were found in this study. These clonal complexes have also been associated with the production of carbapenemases, being CC38 related to a higher proportion of multiresistant strains [2, 54].

In conclusion, this study adds knowledge about the prevalence of ESBL/AmpC-producing bacteria in German pig holdings including antimicrobial resistance and epidemiological data of a large collection of isolates, although it may have some limitations as the absence of comparison with human isolates and the lack of characterization of plasmids involved. However, it contributes important information governing the implementation of appropriate actions in veterinary medicine to reduce the rate of resistant bacteria among food-producing animals and highlights the importance to perform detailed typing studies of isolates from both humans and animals to prove the possible zoonotic transmission from animal to humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank the veterinarians from the Federal Chambers of Agriculture in North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower-Saxony for taking the dust and faecal samples.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper, except the exact geographical coordinates of the participating farms that cannot be published due to confidentiality.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the SafeGuard (grant III-2-03_025) and EurSafety Health-net (grant III-1-02_073) projects within the INTERREG IVa program of the European Union.

References

- 1. Carattoli A. Animal reservoirs for extended spectrum β-lactamase producers. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14: 117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ewers C, Bethe A, Semmler T, Guenther S, Wieler LH. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from livestock and companion animals, and their putative impact on public health: a global perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18: 646–655. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03850.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liebana E, Carattoli A, Coque TM, Hasman H, Magiorakos AP, Mevius D, et al. Public Health Risks of Enterobacterial Isolates Producing Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases or AmpC β-Lactamases in Food and Food-Producing Animals: An EU Perspective of Epidemiology, Analytical Methods, Risk Factors, and Control Options. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56: 1030–1037. 10.1093/cid/cis1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seiffert SN, Hilty M, Perreten V, Endimiani A. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant gram-negative organisms in livestock: An emerging problem for human health? Drug Resist Updat. 2013;16: 22–45. 10.1016/j.drup.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Belmar CC, Fenner I, Wiese N, Lensing C, Christner M, Rohde H, et al. Prevalence and genotypes of extended spectrum beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from human stool and chicken meat in Hamburg, Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304: 678–684. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyer E, Gastmeier P, Kola A, Schwab F. Pet animals and foreign travel are risk factors for colonisation with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli . Infection. 2012;40: 685–687. 10.1007/s15010-012-0324-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valenza G, Nickel S, Pfeifer Y, Eller C, Krupa E, Lehner-Reindi V, et al. Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli as intestinal colonizers in the German community. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58: 1228–30. 10.1128/AAC.01993-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dierikx C, van der Goot J, Fabri T, van Essen-Zandbergen A, Smith H, Mevius D. Extended-spectrum-β-lactamase- and AmpC-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Dutch broilers and broiler farmers. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68: 60–67. 10.1093/jac/dks349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huijbers PM, de Kraker M, Graat EA, van Hoek AH, van Santen MG, de Jong MC, et al. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in humans living in municipalities with high and low broiler density. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19: 256–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Horton RA, Randall LP, Snary EL, Cockrem H, Lotz S, Wearing H, et al. Fecal Carriage and Shedding Density of CTX-M Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli in Cattle, Chickens, and Pigs: Implications for Environmental Contamination and Food Production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77: 3715–3719. 10.1128/AEM.02831-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kola A, Kohler C, Pfeifer Y, Schwab F, Kühn K, Schulz K, et al. High prevalence of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in organic and conventional retail chicken meat, Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67: 2631–34. 10.1093/jac/dks295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Overdevest I, Willemsen I, Rijnsburger M, Eustace A, Xu L, Hawkey PM, et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes of Escherichia coli in chicken meat and humans, The Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17: 1216–1222. 10.3201/eid1707.110209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reuland EA, Naiemi al N, Raadsen SA, Savelkoul PH, Kluytmans JA, Vandenbrouche-Grauls CM. Prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in raw vegetables. Eur J Clin MicrobioL Infect Dis. 2014;33: 1843–1846. 10.1007/s10096-014-2142-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stuart JC, van den Munckhof T, Voets G, Scharringa J, Fluit A, Hall ML. Comparison of ESBL contamination in organic and conventional retail chicken meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;154: 212–214. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leverstein-van Hall MA, Dierikx CM, Stuart JC, Voets GM, van den Munckhof MP, van Essen-Zandbergen A, et al. Dutch patients, retail chicken meat and poultry share the same ESBL genes, plasmids and strains. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17: 873–880. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Been M, Lanza VF, de Toro M, Scharringa J, Dohmen W, Du Y, et al. Dissemination of cephalosporin resistance genes between Escherichia coli strains from farm animals and humans by specific plasmid lineages. PLoS Genet. 2014; 10(12): e1004776 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004776 eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Machado E, Coque MT, Cantón R, Sousa JC, Peixe L. Antibiotic resistance integrons and extended-spectrum β-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae isolates recovered from chickens and swine in Portugal. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62: 296–302 10.1093/jac/dkn179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moodley A, Guardabassi L. Transmission of IncN plasmids carrying blaCTX-M-1 between commensal Escherichia coli in pigs and farm workers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53: 1709–1711. 10.1128/AAC.01014-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodrigues C, Machado E, Peixe L, Novalis A. IncI1/ST3 and IncN/ST1 plasmids drive the spread of bla TEM-52 and bla CTX-M-1/-32 in diverse Escherichia coli clones from different piggeries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68: 2245–2248. 10.1093/jac/dkt187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang J, Stephan R, Karczmarczyk M, Yan Q, Hächler H, Fanning S. Molecular characterization of bla ESBL-harboring conjugative plasmids identified in multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli isolated from food-producing animals and healthy humans. Front Microbiol. 2013;11: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang J, Stephan R, Power K, Yan Q, Hächler H, Fanning S. Nucleotide sequences of 16 transmissible plasmids identified in nine multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolates expressing an ESBL phenotype isolated from food-producing animals and healthy humans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69: 2658–2668. 10.1093/jac/dku206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valentin L, Sharp H, Hille K, Seibt U, Fischer J, Pfeifer Y, et al. Subgrouping of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli from animal and human sources: An approach to quantify the distribution of ESBL types between different reservoirs. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304: 805–816. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smet A, Martel A, Persoons D, Dewulf J, Hevndrickx M, Herman L, et al. Broad-spectrum β-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae of animal origin: molecular aspects, mobility and impact on public health. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34: 295–316. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hering J, Hille K, Frömke C, von Münchhausen C, Hartmann M, Schneider B, et al. Prevalence and potential risk factors for the occurrence of cefotaxime resistant Escherichia coli in German fattening pig farms–a cross-sectional study. Prev Vet Med. 2014;116: 129–137. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2014.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Friese A, Schulz J, Laube H, von Salviati C, Hartung J, Roesler U. Faecal occurrence and emissions of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (laMRSA) and ESbl/AmpC-producing E. coli from animal farms in Germany. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2013;126: 175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. von Salviati H, Laube B, Guerra B, Roesler U, Friese A. Emission of ESBL/AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from pig fattening farms to surrounding areas. Vet Microbiol. 2015;175: 77–84. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goering RV, Köck R, Grundmann H, Werner G, Friedrich AW, ESCMID Study Group for Epidemiological Markers. From theory to practice: molecular strain typing for the clinical and public health setting. Euro Surveill 2013;18(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.EUCAST. Clinical Breakpoints Table v. 5.0. Available: http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/

- 29. Cuzon G, Naas T, Bogaerts P, Clupcynski Y, Nordmann P. Evaluation of a DNA microarray for the rapid detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (TEM, SHV and CTX-M), plasmid-mediated cephalosporinases (CMY-2-like, DHA, FOX, ACC-1, ACT/MIR and CMY-1-like/MOX) and carbapenemases (KPC, OXA-48, VIM, IMP and NDM). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67: 1865–1869. 10.1093/jac/dks156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ortega A, Oteo J, Aranzamendi-Zaldumbide M, Bartolomé RM, Bou G, Cercenado E. Epidemiology and Surveillance: Spanish Multicenter Study of the Epidemiology and Mechanisms of Amoxicillin-Clavulanate Resistance in Escherichia coli . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56: 3576–3581. 10.1128/AAC.06393-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bae IK, Suh B, Jeong SH, Wang KK, Kim YR, Yong D, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Korea producing β-lactamases with extended-spectrum activity. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79: 373–377. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bielaszewska M, Prager R, Köck R, Mellmann A, Zhang W, Tschäpe H, et al. Shiga toxin gene loss and transfer in vitro and in vivo during enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O26 infection in humans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73: 3144–3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deplano A, Denis O, Rodríguez-Villalobos H, De Ryck R, Struelens Marc J, Hallin M. Controlled Performance Evaluation of the DiversiLab Repetitive-Sequence-Based Genotyping System for Typing Multidrug-Resistant Health Care-Associated Bacterial Pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011; 49: 3616–3620. 10.1128/JCM.00528-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Escherichia coli MLST Database. http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli

- 35. Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, Verhulst C, Willemsen LE, Verkade E, Bonten MJM, Kluytmans JAJW. Rectal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in hospitalized patients: selective pre-enrichment increases the yield of screening. J Clin Microbiol. 2015. May 20, 10.1128/JCM.01251-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rayamajhi N, Kang SG, Lee DY, Kang ML, Lee SI, Park KY, et al. Characterization of TEM-, SHV- and AmpC-type β-lactamases from cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from swine. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;124: 183–187. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guerra B, Fischer J, Helmuth R. An emerging public health problem: acquired carbapenemase-producing microorganisms are present in food-producing animals, their environment, companion animals and wild birds. Vet Microbiol. 2014;171: 290–297. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schink AK, Kadlec K, Kaspar H, Mankertz J, Schwarz S. Analysis of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates collected in the GERM-Vet monitoring programme. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68: 1741–1749. 10.1093/jac/dkt123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Strauß LM, Dahms C, Becker K, Kramer A, Kaase M, Mellmann A. Development and evaluation of a novel universal β-lactamase gene subtyping assay for bla SHV, bla TEM and bla CTX-M using clinical and livestock-associated Escherichia coli . J Antimicro Chemother. 2015;70: 710–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gonçalves A, Torres C, Silva N, Carneiro C, Radhouani H, Coelho C, et al. Genetic Characterization of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases in Escherichia coli Isolates of Pigs from a Portuguese Intensive Swine Farm. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010;7: 1569–1573. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hansen KH, Damborg P, Andreasen M, Nielsen SS, Guardabassi L. Carriage and Fecal Counts of Cefotaxime M-Producing Escherichia coli in Pigs: a Longitudinal Study. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79: 794–798. 10.1128/AEM.02399-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Randall LP, Lemma F, Rogers JP, Cheney TE, Powell LF, Teale CJ. Prevalence of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from pigs at slaughter in the UK in 2013. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69: 2947–2950. 10.1093/jac/dku258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kluytmans JAJW, Overdevest ITMA, Willemsen I, Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, van der Zwaluw K, Heck M, et al. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase–Producing Escherichia coli From Retail Chicken Meat and Humans: Comparison of Strains, Plasmids, Resistance Genes, and Virulence Factors Clin Infect Dis. (2013) 56 (4): 478–487 first published online December 14, 2012 10.1093/cid/cis929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Escudero E, Vinue L, Teshager T, Torres C, Moreno MA. Resistance mechanisms and farm-level distribution of fecal Escherichia coli isolates resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in pigs in Spain. Res Vet Sci. 2010;88: 83–87. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2009.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bolton DJ, Ivory C, McDowell D. A study of Salmonella in pigs from birth to carcass: serotypes, genotypes, antibiotic resistance and virulence profiles. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;160: 298–303. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Literak I, Reitschmied T, Bujnakova D, Dolejska M, Cizek A, Bardon J, et al. Broilers as a source of quinolone-resistant and extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in the Czech Republic. Microb Drug Resist. 2013;19: 57–63. 10.1089/mdr.2012.0124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ojer-Usoz E, González D, Vitas AI, Leiva J, García-Jalón I, Febles-Casquero A, et al. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in meat products. Meat Sci. 2012;93: 316–321. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shahada F, Sekizuka T, Kuroda M, Kusumoto M, Ohishi D, Matsumoto A, et al. Characterization of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates harboring a chromosomally encoded CMY-2 beta-lactamase gene located on a multidrug resistance genomic island. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55: 4114–4121. 10.1128/AAC.00560-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shaheen BW, Nayak R, Foley SL, Kweon O, Deck J, Park M, et al. Molecular characterization of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in clinical Escherichia coli isolates from companion animals in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55: 5666–5675. 10.1128/AAC.00656-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thai TH, Yamaguchi R. Molecular characterization of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella isolates from retail meat from markets in Northern Vietnam. J Food Prot. 2012;75: 1709–1714. 10.4315/0362-028X.12-101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu G, Day MJ, Mafura MT, Nunez-García J, Fenner JJ, Sharma M, et al. Comparative Analysis of ESBL-Positive Escherichia coli Isolates from Animals and Humans from the UK, The Netherlands and Germany. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boyd DA, Tyler S, Christianson S, McGeer A, Muller MP, Willey BM, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 92-kilobase plasmid harboring the CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum β-lactamase involved in an outbreak in long-term-care facilities in Toronto, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48: 3758–3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang J, Stephan R, Power K, Yan Q, Hächler H, Fanning S. Nucleotide sequences of 16 transmissible plasmids identified in nine multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolates expressing an ESBL phenotype isolated from food-producing animals and healthy humans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69: 2658–2668. 10.1093/jac/dku206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Oteo J, Diestra K, Juan C, Bautista V, Novais A, Pérez-Vázquez M, et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase- producing Escherichia coli in Spain belong to a large variety of multilocus sequence typing types, including ST10 complex/A, ST23 complex/A and ST131/B2. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34: 173–176. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper, except the exact geographical coordinates of the participating farms that cannot be published due to confidentiality.