Abstract

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a natural oxidant produced by aerobic organisms and gives rise to oxidative damage, including DNA mutations, protein inactivation and lipid damage. The genus Mycobacterium utilizes redox sensors and H2O2 scavenging enzymes for the detoxification of H2O2. To date, the precise response to oxidative stress has not been fully elucidated. Here, we compared the effects of different levels of H2O2 on transcription in M. smegmatis using RNA-sequencing. A 0.2 mM H2O2 treatment had little effect on the growth and viability of M. smegmatis whereas 7 mM H2O2 was lethal. Analysis of global transcription showed that 0.2 mM H2O2 induced relatively few changes in gene expression, whereas a large proportion of the mycobacterial genome was found to be differentially expressed after treatment with 7 mM H2O2. Genes differentially expressed following treatment with 0.2 mM H2O2 included those coding for proteins involved in glycolysis-gluconeogenesis and fatty acid metabolism pathways, and expression of most genes encoding ribosomal proteins was lower following treatment with 7 mM H2O2. Our analysis shows that M. smegmatis utilizes the sigma factor MSMEG_5214 in response to 0.2 mM H2O2, and the RpoE1 sigma factors MSMEG_0573 and MSMEG_0574 in response to 7 mM H2O2. In addition, different transcriptional regulators responded to different levels of H2O2: MSMEG_1919 was induced by 0.2 mM H2O2, while high-level induction of DevR occurred in response to 7 mM H2O2. We detected the induction of different detoxifying enzymes, including genes encoding KatG, AhpD, TrxB and Trx, at different levels of H2O2 and the detoxifying enzymes were expressed at different levels of H2O2. In conclusion, our study reveals the changes in transcription that are induced in response to different levels of H2O2 in M. smegmatis.

Introduction

The genus Mycobacterium includes pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and non-pathogenic microorganisms, such as Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mycobacteria are able to respond to and survive under different stresses [1]. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a natural stressor that is produced by aerobic organisms and leads to oxidative damage, such as DNA mutations, protein inactivation and lipid damage [2]. In addition, when M. tuberculosis, the pathogen which causes human tuberculosis (TB), infects a host, the production of H2O2 is an important innate defense mechanism against infection. As a successful pathogen, M. tuberculosis has evolved redox sensors and H2O2 scavenging enzymes for the detoxification of H2O2 damage [3,4], but the precise response to H2O2 has not been fully elucidated. A number of studies have shown that M. tuberculosis contains several regulators that respond to H2O2 and several enzymes that detoxify H2O2 damage [5–7]. A recent study has reported different transcriptional profiles in M. tuberculosis in response to different H2O2 concentrations [7]. However, the transcriptional response of M. smegmatis to different concentrations of H2O2 has yet to be explored. A greater understanding of the differences between pathogenic M. tuberculosis and nonpathogenic M. smegmatis in their response to H2O2 will help us to understand the pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis.

Transcriptional regulation in response to H2O2 in the Mycobacteria is complex compared to that in Bacillus or Escherichia coli. M. tuberculosis has 13 sigma factors, and M. smegmatis has 28 sigma factors [8,9], of which SigE, SigH, SigL and SigF play important roles in oxidative stress [3]. As classical transcriptional regulators such as OxyR, FNR and FixL are absent in M. tuberculosis, alternative transcriptional regulators have been suggested to be involved in oxidative stress, including FurA [10], IdeR [11], CarD [12], and the WhiB proteins [3]. In addition to transcriptional regulators involved in the response to H2O2, the signal transduction network including two-component systems, one-component systems, and serine/threonine kinases, is also involved in relaying and orchestrating the response to H2O2. M. tuberculosis encodes 11 serine/threonine kinases (STKs), of which PknB, PknF, and PknG have been shown to be involved in the oxidative stress response [13–15]. Park et al. showed that PknB phosphorylates both SigH and its anti-sigma factor RshA and causes its release from the complex of SigH and RshA. The phosphorylated SigH then regulates the response to oxidative stress [14]. Similar to PknB, PknD was shown to phosphorylate anti-anti-sigma factor Rv0516c and then to activate Rv0516c, which changes the expression of the SigF regulon [13]. Moreover, M. tuberculosis produces many enzymes that scavenge H2O2. Mycobacterial KatG is a multifunctional heme-dependent catalase-peroxidase-peroxynitritase [16] and efficiently protects Mycobacterium from reactive oxygen species damage [17]. KatG is the target of the first-line drug isoniazid (INH) and is responsible for the conversion of the prodrug INH into active INH [18]. Clinical strains with decreasing KatG activity showed higher levels of AhpC [19], suggesting that AhpC contributes to defense against oxidative stress. The metabolic enzyme complex with Lpd, SucB, AhpC, and AhpD, is also involved in antioxidant defense [20]. Thiol-dependent peroxidase Tpx is an antioxidant protein against oxidative stress [21]. Voskuil et al. recently investigated whole genome expression in response to different levels of oxidative stress and showed that many genes related to oxidative stress are induced concurrently with the dormancy regulon at high concentrations of H2O2 [7].

In this study, we compared the effects of different H2O2 levels on transcription in M. smegmatis using RNA-sequencing. We show that low levels (0.2 mM) of H2O2 have little effect on the growth and viability of M. smegmatis whereas high levels (7 mM) of H2O2 are bactericidal. Relatively few changes in gene expression were observed on exposure to 0.2 mM H2O2 while a large munber of differentially expressed genes were induced after treatment with 7 mM H2O2. Some differentially expressed genes involved in the glycolysis-gluconeogenesis and fatty acid metabolic pathways were induced by 0.2 mM H2O2, and the expression of genes encoding ribosomal proteins was lower after treatment with 7 mM H2O2. Our analysis also identified differences in the sigma factors, transcriptional regulators, and detoxifying enzymes that are expressed in response to treatment with 0.2 mM and 7 mM H2O2.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Liquid cultures of the M. smegmatis mc2155 strain were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 0.2% (v/v) glycerol (Beijing Modern Eastern Finechemical), 0.05% Tween 80 (v/v) (Sigma) and 10% ADS (albumin, dextrose, and saline). Middlebrook 7H10 medium (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 10% ADS and 0.2% (v/v) glycerol was used as the solid medium for M. smegmatis growth.

Response of the M. smegmatis mc2155 strain to H2O2 stress

Log phase cultures (OD600 of 0.8–1.0) of M. smegmatis mc2155 were diluted 1:100 into 7H9 media and cultured for approximately 12 hours until the OD600 reached 0.3. Re-inoculated cells were then treated with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 (0, 0.2 and 7 mM) for periods of 30 min or 3 h, and surviving cells were grown on 7H10 media. Cells were collected after 30 min of 0.2 mM or 7 mM H2O2 treatment, and total RNA was isolated from each sample and compared by RNA-sequencing to RNA from untreated cells that were prepared simultaneously.

RNA isolation for RNA-sequencing

Fifty milliliters of bacterial culture (OD600 of ~ 0.3) was collected and total RNA was isolated using FastPrep Purification kits (MP Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Construction and sequencing of the cDNA libraries of the various mycobacterial strains was performed by BGI-Shenzhen (China). Briefly, total RNA from treated mc2155 strains was treated using a Ribominus Transcriptome Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to remove rRNA contaminations. NEXTflex RNA Fragmentation Buffer (Bioo Scientific) was added to separate the mRNA into short fragments. Using these short fragments as templates, random hexamer-primers were used to synthesize the first strand of cDNA. The second strand of cDNA was synthesized using buffer, dNTPs, RNase H and DNA polymerase I. The short fragments were purified with a QIAQuick PCR extraction kit (QIAGEN) and resolved with EB buffer for end reparation and addition of poly(A). The short fragments were subsequently connected with sequencing adaptors. For amplification by PCR, we selected suitable fragments as templates, based on results of agarose gel electrophoresis. The library was then sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2000. Clean reads were mapped to the reference genome and the gene sequences using SOAP2 [22]. The RNA-sequencing dataset obtained has been submitted to ArrayExpress under the accession number E-MTAB-3594.

RNA-sequencing data analysis

The raw data were filtered to 1) remove reads with adaptors, 2) remove reads with more than 10% of unknown nucleotides, 3) remove low quality reads (in which more than half of the base quality scores were less than 5). The resulting cleaned paired-end reads were mapped to the M. smegmatis mc2155 reference genome (NC 008596.1) using SOAP2. Mismatches of no more than 5 bases were allowed in the alignment. We performed statistical analysis in read alignments on the genome and genes for each sample. Randomness of the mRNA/cDNA fragmentation was evaluated using the reads distribution of reference genes.

Gene expression was calculated according to the RPKM method (reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads) [23], and eliminated the biases influence of different gene length and sequencing difference using the TPM method [24]. We calculated the ratio of each gene between samples and identified genes differentially expressed between two samples using "the significance of digital gene expression profiles" [25] based on the criteria FDR ≤ 0.001 and a fold change larger than 4. STRING (9.1) [26] was used to analyze the interactions of differentially expressed genes and functional and pathway enrichment analysis. A p-value less than 0.05 was used as a threshold to indicate significant enrichment.

Quantitative PCR of selected genes

Log phase cultures (OD600 = 0.8–1.0) of all the tested strains were diluted 1:100 in 7H9 media. The strains were cultured until the OD600 reached 0.3 and then divided into control and treatment groups. In the treatment group, the cells were treated with 0.2 or 7 mM H2O2 for 30 min and then collected by centrifugation at 12,000 x g. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA), and RNA was purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in a Bio-Rad iCycler using a 2x SYBR real-time PCR pre-mix (Takara Biotechnology Inc., Japan). The following cycling program was used: 95°C for 1.5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s, followed by 72°C for 6 min. The M. smegmatis rpoD gene encoding the RNA polymerase sigma factor SigA was selected as a reference gene for normalizing gene expression. The 2-ΔΔCT method was used [27] to evaluate relative gene expression in the different strains and/or different treatments. All primers used are listed in S1 Table.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0c. Significant differences in the data were determined using t-tests.

Results and Discussion

Effects of H2O2 on growth and viability

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a natural oxidant produced by aerobic organisms and can lead to oxidative damage, such as DNA mutations, protein inactivation and drug resistance [2]. In addition, increasing levels of toxic H2O2 in the infected host is an important defensive mechanism against invading pathogens. Resistance to H2O2 might increase bacterial survival in mycobacterial-infected macrophages. A previous study from our lab showed that increased resistance to H2O2 in a mutant strain of M. smegmatis could lead to higher survival in infected macrophages [28]. M. tuberculosis can persist in macrophages for decades, partly because it possesses many regulators that respond to H2O2 and many enzymes that detoxify H2O2 [3,7]. A recent study analyzed genome-wide changes in gene expression in response to different levels of oxidative and nitrosative stresses in M. tuberculosis [7]. Responses to oxidative and nitrosative stresses were compared and their results revealed a common genetic response used by M. tuberculosis in response to these stresses. This study demonstrated that analyzing global transcription levels can help us understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the response of bacteria to H2O2. Here, we examined the global transcriptional response of M. smegmatis to different levels of H2O2 using RNA-sequencing.

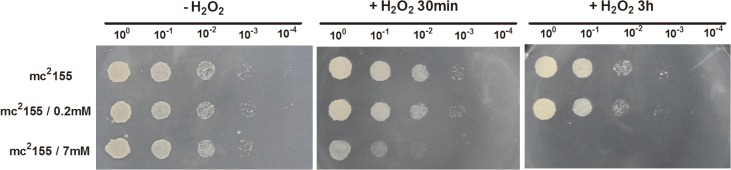

Bacteria are most sensitive to environmental stresses at the early logarithmic phase [29]. We therefore chose to treat the M. smegmatis strain mc2155 with H2O2 when bacteria reached the early logarithmic phase of growth (optical density, OD600 of ~ 0.3). We have previously reported that, under experimental conditions in our laboratory, the MIC to H2O2 in M. smegmatis is 0.039 mM [28] and that of M. tuberculosis is 1mM. The ratio of the MIC to H2O2 of M. smegmatis to M. tuberculosis is ~26. In order to compare the response of M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis to H2O2, we used concentrations of H2O2 comparable to those used in Voskuil et al [7]. Here we used an H2O2 concentration of 7mM for M. smegmatis to correspond to the 200 mM H2O2 treatment used by Voskuil et al. in M. tuberculosis. Similarly, the 0.2 mM H2O2 treatment used here corresponded to the ~ 5 mM H2O2 treatment used by Voskuil et al in M. tuberculosis. When the M. smegmatis mc2155 strain reached the early logarithmic phase, bacterial cultures were exposed to two different H2O2 concentrations, namely 0.2 mM or 7 mM for either 30 min or 3 h, and cultures were then collected and spotted onto 7H10 media. As shown in Fig 1, no growth differences were detected between the bacteria treated with 0.2 mM for 30 min or 3 h and untreated control bacteria, indicating that exposure to 0.2 mM H2O2 had little effect on bacterial growth and viability. In contrast, when cultures were treated with 7 mM H2O2, we observed that exposure to 7 mM H2O2 resulted in a significant decrease in cell survival (Fig 1), indicating that 7 mM H2O2 has a bactericidal effect in M. smegmatis. Moreover, the genes induced in response to H2O2 (5–10 mM) in the Voskuil study were also found to be induced in M. tuberculosis during infection of activated macrophages[30], indicating that a level of 5–10 mM H2O2 is similar to that experienced by bacteria within infected macrophage. Here, the response of 7 mM of H2O2 used to examine the M. smegmatis response might suggest the response of bacteria within infected macrophage.

Fig 1. The effect of H2O2 stress on the survival of M. smegmatis.

The panel represents serial dilutions (1:10) of mc2155 cultures treated with 0.2 mM or 7 mM H2O2 for either 30 min or 3 hour. Three microliters of diluted M. smegmatis cultures were spotted onto solid 7H10 medium. Images shown are representative of at least 3 experiments.

The following experiments were performed to compare the transcriptional response of M. smegmatis exposed to 0.2 mM H2O2 or 7 mM H2O2 for 30 min when bacterial growth had reached an OD600 of 0.3.

Expression profiles of M. smegmatis in response to different levels of H2O2

Transcriptional reprogramming is a critical step in bacterial responses to various stress factors to ensure their survival. We therefore examined changes in mRNA expression following treatment with H2O2 using RNA-sequencing. mRNA samples from of M. smegmatis mc2155 with or without H2O2 treatment were prepared as described in the “Materials and Methods”.

RNA-sequencing mapping statistics showed that approximately 96% of the sequencing reads could be mapped to the M. smegmatis reference genome (NC_008596.1) (Table 1). The percentage of unique mapped reads for untreated mc2155, mc2155 treated with 0.2 mM H2O2 and mc2155 treated with 7 mM H2O2 were 92.34%, 98.28% and 98.17%, respectively and the number of reads mapped was 6089174, 6390446 and 6548357, respectively.

Table 1. RNA-sequencing mapping statistics.

| Sample name | mc2155 | mc2155 / 0.2 mM | mc2155/ 7 mM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reads number | Percentage | Reads number | Percentage | Reads number | Percentage | |

| Total reads | 6594442 | 100.00% | 6502552 | 100.00% | 6670090 | 100.00% |

| Total base pairs | 593499780 | 100.00% | 585229680 | 100.00% | 600308100 | 100.00% |

| Total Mapped Reads | 6089174 | 92.34% | 6390446 | 98.28% | 6548357 | 98.17% |

| Perfect match | 4382586 | 66.46% | 5499445 | 84.57% | 5525430 | 82.84% |

| ≤ 5bp mismatch | 1706588 | 25.88% | 891001 | 13.70% | 1022927 | 15.34% |

| Unique match | 5818976 | 88.24% | 6065452 | 93.28% | 6171788 | 92.53% |

| Multi-position match | 270198 | 4.10% | 324994 | 5.00% | 376569 | 5.65% |

| Total unmapped reads | 505268 | 7.66% | 112106 | 1.72% | 121733 | 1.83% |

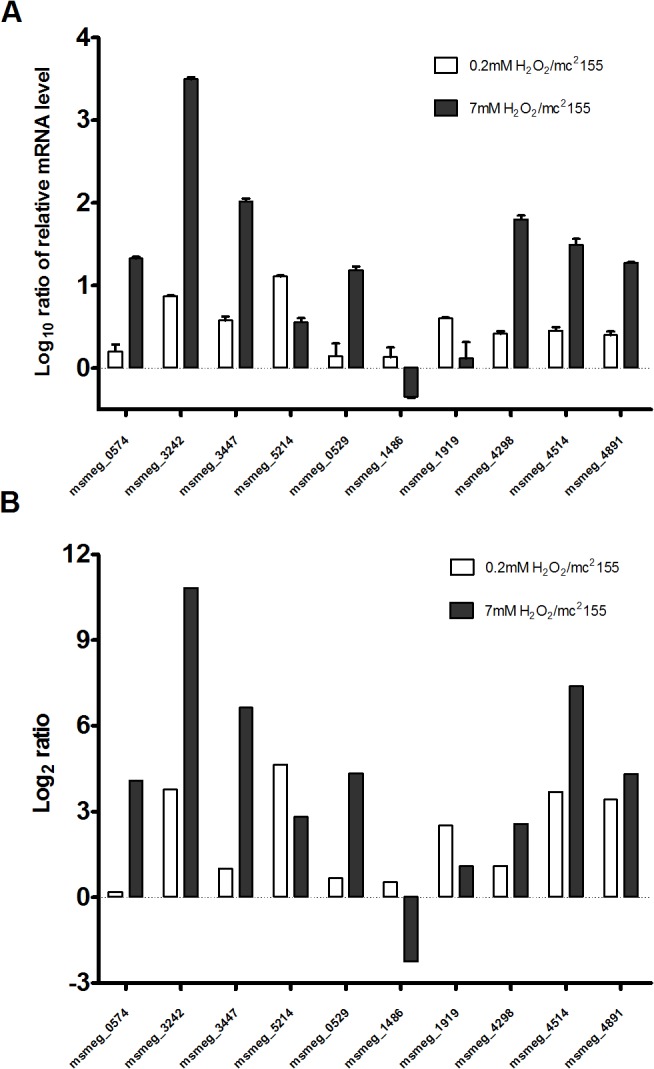

Fully annotated data are presented in S2–S4 Tables. Genes were considered to be significantly differentially expressed if their changes in expression were > 4-fold greater compared to the non-treated wild type mc2155 strain, with a false discovery rate (FDR) corrected P-value of < 0.01. To confirm the results obtained from the RNA-sequencing analysis (Fig 2B), several induced genes were examined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). In three independent experiments, total RNA was isolated from M. smegmatis exposed to 0.2 mM or 7 mM H2O2 for 30 min and relative levels of expression were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Results were consistent with those obtained from RNA-sequencing results, confirming the validity of our approach. For example, msmeg_0574 exhibited a 21.17 ± 1.11-fold enhancement when induced by 7 mM H2O2, but little enhancement (1.61 ± 0.31-fold) when induced by 0.2 mM H2O2 (Fig 2A), consistent with RNA-sequencing results (Fig 2B). In addition, msmeg_3242 exhibited a 3116.9 ± 182.8-fold enhancement when induced by 7 mM H2O2 and a 7.43 ± 0.11-fold enhancement when induced by 0.2 mM H2O2 (Fig 2A). The relative expression levels of the genes we chose to test under 0.2 mM and 7 mM H2O2 were also consistent with RNA-sequencing results (Fig 2). In summary, these results support the fidelity of the RNA-sequencing results for the analysis below.

Fig 2. Quantitative RT-PCR validation of RNA-sequencing results.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the mRNA expression of genes differentially expressed after treatment with different levels of H2O2. M. smegmatis cultures were treated with 2 mM or 7 mM H2O2 for 30 min before extraction of RNA for qRT-PCR. The data represent 3 independent experiments. (B) Fold changes of selected genes differentially expressed genes after treatment with 0.2 mM and 7 mM H2O2 obtained by the RNA-sequencing.

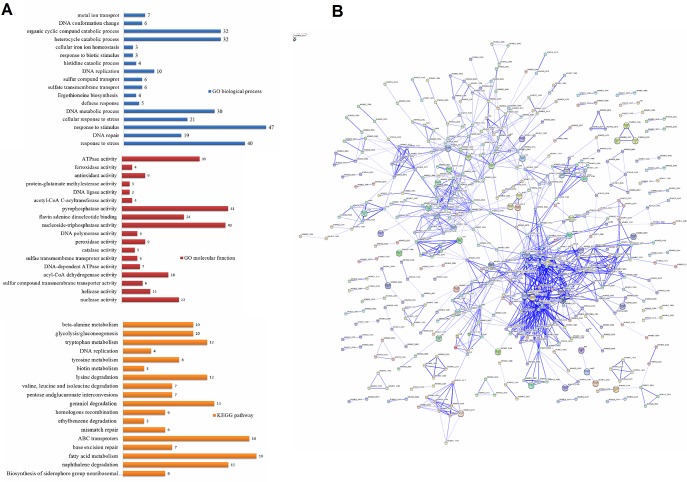

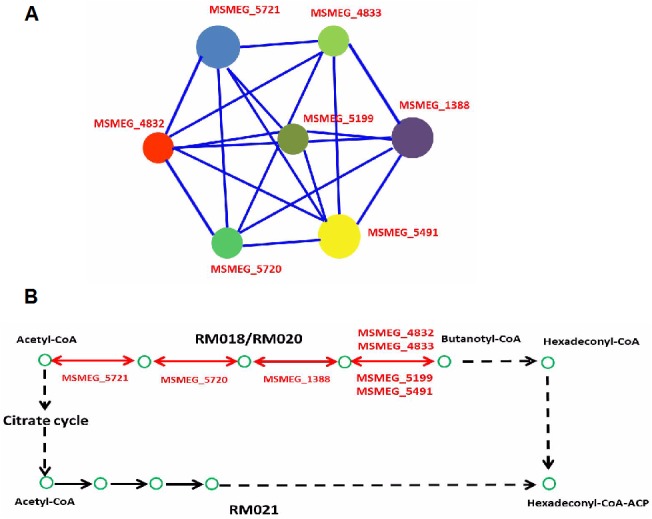

Upon exposure to 0.2 mM H2O2, there were 303 up-regulated genes and 331 down-regulated genes. Genes differentially expressed in the mc2155 strain on treatment with 0.2 mM H2O2 were significantly enriched for several GO biological processes, including response to stress (p = 1.44 x 10−10), DNA repair (p = 2.87 x 10−5), and ergothioneine biosynthesis (p = 1.18 x 10−2) when compared to the untreated mc2155 strain (Fig 3A). In GO molecular function categories, we found that genes differentially expressed after treatment with 0.2 mM H2O2 were significantly enriched for nuclease activity (p = 2.49 x10-4), helicase activity (p = 4.55 x 10−2), and sulfur compound transmembrane transporter activity (p = 4.55 x 10−2) when compared to the untreated mc2155 strain (Fig 3A). As H2O2 causes DNA damage, genes involved in DNA repair (listed in Table 2) were induced upon exposure to 0.2 mM H2O2. Induction of RecA, AlkA, and DNA helicase by H2O2 was also found in the M. tuberculosis study [7]. M. tuberculosis RecA is involved in nucleotide excision, recombination and the SOS response [31]. In M. smegmatis, RecA is induced by DNA damage and is a key regulator element of the SOS response [32]. In M. tuberculosis, dnaE2, which encodes an error–prone DNA polymerase, was shown to increase its expression in response to DNA damaging agents, suggesting that its role is involved in damage tolerance [33,34]. mRNA levels of M. smegmatis dnaE2 and recA were increased 46-fold and 12-fold, respectively, by 0.2 mM H2O2, and 5-fold and 7.8-fold, respectively, by 7 mM H2O2 (Table 2). The response profiles with high inductions of DNA repair genes in M. smegmatis by both low (0.2 mM) and high (7 mM) levels of H2O2 were strikingly different to those in M. tuberculosis which showed high induction from mild levels of H2O2 and no change in induction with bactericidal H2O2 levels [7]. Future work should compare and investigate differences between M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis in DNA-damage-mediated death caused by H2O2 in order to provide greater insights into the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis. The STRING database was used to establish protein interaction networks of physical and functional interactions among the differentially expressed genes identified (Fig 3B). Interestingly, using the KEGG-User Data Mapping [35] (Fig 4B), seven genes involved in fatty acid metabolism (RM018 and RM020) were found and formed an interconnected cluster (Table 2 and Fig 4A). In addition, nine genes involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (msm00010) were found in a partially interconnected cluster (Table 2). Transcription of these genes was induced, suggesting that these differentially expressed genes are involved in the central carbon metabolism (CCM) switch and providing supporting evidence for a previous suggestion that the CCM of M. tuberculosis plays important roles in growth and pathogenicity [36,37]. An extensive transcriptional switch in M. tuberculosis CCM genes during host infection has been reported, indicating that there is a quick change in the metabolic pathway in response to various stresses [38]. The gene pdhB involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis was repressed 9.7-fold by 0.2 mM H2O2, and pdhA was repressed 11-fold. PdhA and PdhB are constituents of the mycobacterial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex which connects glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [39]. In contrast to cells treated with 7 mM H2O2, changes induced in pdhA and pdhB in the 0.2 mM treatment were weak (Table 2). Similarly, the seven differentially expressed genes induced by 0.2 mM were involved in fatty acid metabolism and decreased by 4 to 6-fold (Table 2), whereas a decrease induction did not appear after the 7 mM H2O2 treatment. Together, these results suggest that the metabolic switch of glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and fatty acid metabolism was specific to induction by 0.2 mM H2O2.

Fig 3. Overview of the differential expression profiles in response to 0.2 mM H2O2 in M. smegmatis.

(A) Enrichment analysis. The differently colored bars indicate the gene number for the enrichment of the annotations. (B) Interaction network of the differentially expressed genes of M. smegmatis induced by 0.2 mM H2O2 using STRING (9.1) at confidence scores ≥ 0.4. The network is enriched among the 634 differentially expressed genes and 111 interactions were observed (p value = 0).

Table 2. Fold changes of genes differentially expressed after treatment with 0.2 mM and 7 mM H2O2 (treated vs untreated).

| Gene Name | Gene Product | log2 Ratio (0.2mM/mc2155) | P-value | FDR | log2 Ratio (7mM/mc2155) | P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA repair | |||||||

| msmeg_2839 | transcriptional accessory protein | -1.7523338 | 2.02E-243 | 5.7E-242 | -1.6975845 | 9.0323E-80 | 5.4177E-79 |

| alkA | methylated-DNA—protein-cysteine methyltransferase | -2.106759 | 8.54E-09 | 2.73E-08 | -1.1090648 | 0.00020253 | 0.00030498 |

| msmeg_1383 | endonuclease IV | -2.8849149 | 0 | 0 | -0.4418784 | 0 | 0 |

| msmeg_1756 | endonuclease VIII and DNA N-glycosylase with an AP lyase activity | 3.01822392 | 2.08E-105 | 3.04E-104 | 2.96577039 | 9.82E-104 | 7.22E-103 |

| dnaE2 | error-prone DNA polymerase | 5.52502439 | 0 | 0 | 2.44964676 | 1.32E-277 | 2.48E-276 |

| lig | ATP-dependent DNA ligase | 2.37386688 | 1.03E-184 | 2.21E-183 | 1.60677746 | 5.66E-69 | 3E-68 |

| ligA | NAD-dependent DNA ligase LigA | 2.32734432 | 0 | 0 | 2.47575753 | 0 | 0 |

| recA | recombinase A | 3.59091497 | 0 | 0 | 2.96402929 | 0 | 0 |

| uvrB | excinuclease ABC subunit B | 3.25788081 | 0 | 0 | 4.50884994 | 0 | 0 |

| lexA | LexA repressor | 3.10981267 | 0 | 0 | 1.01678782 | 4.81E-103 | 3.51E-102 |

| radA | DNA repair protein RadA | 2.82617738 | 0 | 0 | 1.71244303 | 0 | 0 |

| dinP | DNA polymerase IV | 4.26301055 | 1.85E-174 | 3.84E-173 | 4.18732816 | 2.79E-169 | 3.17E-168 |

| msmeg_1622 | putative DNA repair polymerase | 4.79317887 | 8.44E-277 | 2.71E-275 | -0.1339395 | 0.658812 | 0.69126208 |

| recD | exodeoxyribonuclease V, alpha subunit | 3.50057135 | 3.24E-216 | 8.07E-215 | 2.03125644 | 2.04E-46 | 8.42E-46 |

| msmeg_1756 | endonuclease VIII and DNA N-glycosylase with an AP lyase activity | 3.01822392 | 2.08E-105 | 3.04E-104 | 2.96577039 | 9.82E-104 | 7.22E-103 |

| helicase | ATP-dependent DNA helicase | 4.16679804 | 0 | 0 | 4.74283172 | 0 | 0 |

| tag | DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase I | 2.81384991 | 2.09E-184 | 4.47E-183 | 2.86173411 | 2.34E-201 | 3.15E-200 |

| Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | |||||||

| msmeg_1543 | eptc-inducible aldehyde dehydrogenase | -2.6859775 | 8.91E-139 | 4.21E-148 | -1.2892582 | 5.64E-56 | 2.60E-55 |

| msmeg_1762 | piperideine-6-carboxylic acid dehydrogenase | 2.93235592 | 2.30E-149 | 4.21E-148 | -1.6876011 | 2.28E-12 | 4.83E-12 |

| pfkB | 6-phosphofructokinase isozyme 2 | -5.7653785 | 3.88E-196 | 8.90E-195 | -2.8501465 | 6.61E-126 | 5.73E-125 |

| pdhB | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta | -3.2722769 | 3.01E-30 | 1.92E-29 | 0.71595693 | 5.59E-07 | 9.61E-07 |

| pdhA | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component, alpha subunit | -3.4705711 | 1.84E-89 | 2.39E-88 | -0.3895867 | 0.00010596 | 0.00016157 |

| adhB | alcohol dehydrogenase B | -4.0478653 | 2.97E-105 | 4.33E-104 | -2.1612025 | 4.92E-60 | 2.38E-59 |

| msmeg_6616 | S-(hydroxymethyl)glutathione dehydrogenase | -2.956082 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | -1.1422205 | 1.36E-159 | 1.45E-158 |

| msmeg_6687 | aldehyde dehydrogenase, thermostable | -3.706221 | 1.64E-29 | 1.03E-28 | -1.5049935 | 9.36E-12 | 1.94E-11 |

| msmeg_6834 | alcohol dehydrogenase | -2.7848309 | 2.21E-05 | 5.51E-05 | 0.08733237 | 0.840712 | 0.85579383 |

| fadA | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | -2.7273404 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 0.33348045 | 5.36E-35 | 1.86E-34 |

| fadB | putative 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase | -2.6949142 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 1.39743214 | 0 | 0 |

| msmeg_5199 | putative acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | -2.6174798 | 7.78E-91 | 1.02E-89 | -0.4351779 | 5.88E-07 | 1.01E-06 |

| msmeg_4832 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | -2.2726247 | 1.84E-34 | 1.30E-33 | -1.4448556 | 2.45E-20 | 6.42E-20 |

| msmeg_4833 | putative acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | -2.176661 | 8.50E-49 | 7.39E-48 | -2.3488919 | 3.50E-57 | 1.65E-56 |

| echA4 | enoyl-CoA hydratase | -2.5812975 | 1.27E-32 | 8.59E-32 | -0.1876747 | 0.1805012 | 0.20801109 |

| fadE13 | putative acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | -2.4369076 | 3.84E-11 | 1.38E-10 | -0.1310912 | 0.579156 | 0.6139111 |

| Sigma factors | |||||||

| sigG | RNA polymerase factor sigma-70 | 2.93398738 | 0 | 0 | 3.88123043 | 0 | 0 |

| msmeg_0573 | putative ECG sigma factor RpoE1 | 1.38509413 | 0.0569946 | 0.08901435 | 7.09387521 | 1.35E-209 | 1.91E-208 |

| msmeg_0574 | putative ECG sigma factor RpoE1 | 0.18840222 | 0.422278 | 0.5067336 | 4.08443636 | 3.1E-276 | 5.78E-275 |

| msmeg_1348 | RNA polymerase ECF-subfamily protein sigma factor | -0.0465176 | 0.804554 | 0.84797939 | -2.3586787 | 1E-17 | 2.48E-17 |

| sigL | RNA polymerase sigma factor SigL | 0.52825986 | 0.00083713 | 0.00176811 | -2.2355973 | 4.27E-20 | 1.12E-19 |

| msmeg_1970 | sigma factor | -1.6126499 | 4.2715E-20 | 1.1152E-19 | -4.1999183 | 4.27E-20 | 1.12E-19 |

| mysB | RNA polymerase sigma factor SigB | -0.4921846 | 4.74E-104 | 6.85E-103 | 2.50111799 | 0 | 0 |

| msmeg_3008 | putative sigma 54 type regulator | -1.8964762 | 1.61E-11 | 5.87E-11 | -2.0197975 | 3.44E-13 | 7.46E-13 |

| msmeg_5214 | RNA polymerase sigma-70 factor | 4.65312922 | 2.09E-184 | 4.47E-183 | 2.81376729 | 1.63E-13 | 3.59E-13 |

| msmeg_5444 | RNA polymerase sigma-70 factor protein | 0.03717083 | 0.894318 | 0.91679688 | -2.0919913 | 9.72E-09 | 1.8E-08 |

| Transcriptional Regulators | |||||||

| devR | two-component system response regulator | 1.01514452 | 0.00136283 | 0.00280756 | 6.64431111 | 0 | 0 |

| furA (msmeg_6383) | transcription regulator FurA | 2.0393827 | 1.57E-38 | 1.19E-37 | 4.16725591 | 0 | 0 |

| phoP | DNA-binding response regulator PhoP | 2.90191537 | 4.67E-220 | 1.19E-218 | -0.5325639 | 0.00089158 | 0.00128064 |

| msmeg_4517 | TetR-type transcriptional regulator of sulfur metabolism | 3.21516913 | 0.00000169 | 0.00000457 | 4.13040109 | 7.31E-14 | 1.62E-13 |

| msmeg_4925 | transcriptional regulator | 0.69321643 | 0.00330216 | 0.00644626 | 2.93688979 | 1.02E-78 | 6.03E-78 |

| msmeg_1919 | Transcription factor WhiB | 2.52297686 | 0 | 0 | 1.07820136 | 2.53E-126 | 2.21E-125 |

| msmeg_4025 | transcriptional regulator, LysR family protein | 1.30263197 | 0.00055968 | 0.00120459 | 5.38130323 | 1.6E-210 | 2.28E-209 |

| msmeg_6253 | fur family protein transcriptional regulator | 1.24070422 | 0.0469844 | 0.07479434 | 3.90800867 | 1.22E-25 | 3.59E-25 |

| Detoxification enzymes | |||||||

| trxB | thioredoxin-disulfide reductase | -0.0780198 | 0.1478068 | 0.20755437 | 2.71109242 | 0 | 0 |

| trx | thioredoxin | 0.12205973 | 0.0602136 | 0.09347541 | 3.84889994 | 0 | 0 |

| msmeg_6884 | NADP oxidoreductase | 0.87052096 | 0.1166366 | 0.1680318 | 4.68101209 | 4.52E-68 | 2.38E-67 |

| KatG | catalase/peroxidase HPI | 3.82587233 | 0 | 0 | 4.95397834 | 0 | 0 |

| msmeg_4890 | alkylhydroperoxidase | 3.42735043 | 6.73E-19 | 3.21E-18 | 4.22476909 | 0.0465926 | 0.05777446 |

| msmeg_3448 | two-component system sensor kinase | 0.55015338 | 0.1588256 | 0.22100457 | 5.07235098 | 4.09E-202 | 5.55E-201 |

| ahpD | alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD core | -2.3697934 | 0.0210456 | 0.03618406 | 3.85029317 | 4.71E-31 | 1.53E-30 |

| msmeg_3708 | catalase | 2.47422002 | 5.45E-56 | 5.11E-55 | -3.0001305 | 5.73E-15 | 1.31E-14 |

Fig 4. Connected network of the enriched differentially expressed genes following exposure to 0.2 mM H2O2.

(A) Connected network of enriched differentially expressed genes involved in fatty acid metabolism (RM018 and RM020). (B) Partial fatty acid metabolism in M. smegmatis. Genes expressed differentially after 0.2 mM H2O2 treatment assigned to RM018 and RM020 are marked in red.

Compared to the down-regulation of 331 genes under the 0.2 mM H2O2 treatment, 1671 genes were down-regulated under the 7 mM H2O2 treatment and 343 genes were up-regulated. In contrast to the small proportion of genes in the genome that responded to the 0.2 mM H2O2 treatment (663 differentially-expressed genes, ~10% of the genes in the M. smegmatis genome), 2002 genes were induced in response to 7 mM H2O2, representing 29.3% of the genes in the M. smegmatis genome. In contrast to the interaction networks obtained among genes which showed differential expression at the mRNA level in response to the 0.2mM H2O2 treatment, we did not find enrichment in specific metabolic pathways among genes that were differentially expressed in response to the 7 mM H2O2 treatment. This might be due to the fact that the 7 mM H2O2 treatment had more global effects on transcription, which were not limited to specific metabolic pathways. We also conducted an analysis of GO biological processes and identified enrichment in processes including gene expression (p = 2.47 x 10−1), macromolecule biosynthetic processes (p = 2.47 x 10−1) and regulation of gene expression (p = 2.84 x 10−1) (S1 Fig). Ribosome biogenesis was also enriched, though the P-value was 5.48 x 10−1, slightly higher than the cutoff value (P < 0.5). Oxidative stress results in the rapid inhibition of protein synthesis as well as in the reprogramming of gene expression, resulting in growth reduction as an adaption to oxidative stress [40].

Responses of specific genes to exposure to low and high levels of H2O2

Mycobacterium utilizes diverse antioxidant systems to combat H2O2 stress, including sigma factors, transcriptional regulators, STKs and detoxifying enzymes. To further clarify the responses to different levels of H2O2 stress, we compared the biological categories involved in oxidative stress. In M. tuberculosis, sigma factors (such as SigE, SigH, SigL and SigF) are important for initiating the H2O2 detoxification pathway [7], and so we examined the response of sigma factors to different levels of H2O2 in M. smegmatis. We did not find any differences in the expression of sigF in the 0, 0.2 mM, and 7 mM H2O2 treatments. SigF was first described as a stationary-phase stress response sigma factor in M. tuberculosis [41], and we have previously shown that SigF is involved in the oxidative stress response in mycobacteria [41,42]. Lack of SigF induction here may have been due to the fact that SigF is a stationary-phase stress response sigma factor and does not function at the early logarithmic phase, which was used in this study. It will be interesting to compare the global transcriptional response to H2O2 at different growth phases. While Voskuil et al. conducted studies showing that M. tuberculosis SigH is highly induced upon exposure to high levels of H2O2 [7], here, M. smegmatis SigH was moderately induced at both low and high stresses (data not shown). The gene msmeg_0573, which encodes the ECF sigma factor RpoE1, was the most highly induced sigma factor, exhibiting a 136-fold increase in expression following the 7 mM H2O2 treatment. No change in its expression was observed following the 0.2 mM H2O2 treatment. Its paralog, msmeg_0574, which encodes the ECF sigma factor RpoE1, was also specifically induced (~17-fold) by 7 mM H2O2. These results showed that both MSMEG_0573 and MSMEG_0574 are specifically induced by 7 mM H2O2. In contrast, msmeg_5214, which encodes the RNA polymerase sigma-70 factor, was specifically up-regulated in 0.2 mM H2O2 (Table 2). Together, these data indicate that distinct sigma factor genes respond to different levels of H2O2. In addition to sigma factors, transcriptional regulators also have important roles in the regulation of the oxidative stress response. As M. tuberculosis does not have a functional OxyR, the transcription regulators FurA, IdeR, CarD and WhiB play important roles in the oxidative stress response. FurA was induced 4-fold at 0.2 mM H2O2 and 18-fold at 7 mM H2O2. Furthermore, no significant changes were found in IdeR and CarD expression levels at either 0.2 mM or 7 mM H2O2. The M. smegmatis genome contains six whiB genes, and only MSMEG_1919 was induced by 0.2 mM H2O2 (Table 2). DevR has previously been shown to be highly induced in M. tuberculosis only when exposed to high concentrations of H2O2 [7]. Consistent with this report, our results showed that in M. smegmatis, devR expression was mildly increased by 0.2 mM and strongly increased (100-fold) after treatment with 7 mM H2O2 treatment (Table 2). We next compared the transcription responses of genes coding for serine/threonine-protein kinases (SPTKs) to H2O2 exposure. Of the STPKs, we found that following 7 mM H2O2 treatment, only pknK was up-regulated. M. tuberculosis PknK has been shown to regulate the slow growth of mycobacteria in response to various stresses and during persistence in infected mice [43]. Just as PknK is involved in the oxidative stress response pathway in M. tuberculosis, PknK plays an important role in M. smegmatis in regulating the response to high levels of H2O2. The functions of PknK and its involvement in the response to H2O2 require further exploration.

The M. smegmatis genome encodes several enzymes involved in the detoxification of H2O2 [4,8]. Our analysis showed that mRNA levels of katG were up-regulated 12-fold and 30-fold following exposure to 0.2 and 7 mM H2O2 respectively (Table 2). Notably, trxB (encoding thioredoxin-disulfide reductase) and trx (encoding thioredoxin) expression was induced strongly by 7 mM H2O2 treatment (Table 2), but not by 0.2 mM H2O2. Similarily, ahpD (encoding alkylhydroperoxidase) and msmeg_6884 (encoding NADP oxidoreductase) responded to 7 mM H2O2 but not to 0.2 mM H2O2. msmeg_3708 (encoding catalase) exhibited a 5-fold increase in mRNA expression only after exposure to 0.2 mM H2O2, indicating that it is specifically induced in response to low levels of H2O2 exposure. It will be interesting to investigate the distinct biological roles of enzymes that scavenge different levels of H2O2 in mycobacteria. Such studies will lead to greater understanding of the basic roles of these enzymes.

Conclusion

In this study, we have shown that, in M. smegmatis, different genes are induced in response to low and high levels of H2O2. A notable difference in the response to low-level (0.2 mM) H2O2 and high-level (7 mM) H2O2 was observed. When exposed to 0.2 mM H2O2, expression of approximately 10% of the genes in the M. smegmatis genome was significantly changed. In contrast, 29.3% of M. smegmatis genes were significantly changed in response to 7 mM H2O2. Transcriptional analysis suggested that a metabolic switch in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and fatty acid metabolism was potentially involved in the response to the 0.2 mM H2O2 treatment but not to the 7 mM H2O2 treatment. We also observed that transcriptional levels of genes encoding ribosomes decreased when bacterial cells were treated with 7 mM H2O2. This result suggests that 7 mM H2O2 treatment affected the protein synthesis apparatus and thus reduced protein synthesis, resulting in reduced bacterial growth. The expression level of gene msmeg_5214 (encoding the RNA polymerase sigma-70 factor) was induced in response to 0.2 mM H2O2, and the rpoE1s (msmeg_0573 and msmeg_0574) were induced specifically in response to 7 mM H2O2. In addition, different regulators were observed to respond to different levels of H2O2. MSMEG_1919 was induced following exposure to 0.2 mM H2O2, while DevR was highly induced by the 7 mM H2O2 treatment. Our results show that pknK, a gene encoding a STPK, is involved in the 7 mM H2O2 treatment response and that different genes encoding detoxifying enzymes, including the genes encoding KatG, AhpD, TrxB and Trx, were expressed in response to different levels of H2O2. In summary, this study of global transcriptional changes that occur after exposure to different levels of H2O2 documents changes in transcriptional regulation in response to exposure to low and high level H2O2 treatments, including the use of different sigma factors, regulators, serine/threonine kinases and differences in the transcriptional levels of detoxifying enzymes used to combat H2O2 stress. Further study of these genes will aid our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the precise regulation and scavenging of H2O2.

Supporting Information

(JPG)

(DOC)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB518700 and 2014CB744400) and the Key Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KJZD-EW-L02).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. The dataset of RNA-sequencing has been submitted to ArrayExpress under the accession number E-MTAB-3594.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB518700 and 2014CB744400) and the Key Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KJZD-EW-L02).

References

- 1. Zahrt TC, Deretic V. Reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates and bacterial defenses: unusual adaptations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2002;4(1):141–59. 10.1089/152308602753625924 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Imlay JA. The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2013;11(7):443–54. 10.1038/nrmicro3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhat SA, Singh N, Trivedi A, Kansal P, Gupta P, Kumar A. The mechanism of redox sensing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;53(8):1625–41. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mishra S, Imlay J. Why do bacteria use so many enzymes to scavenge hydrogen peroxide? Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2012;525(2):145–60. 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cirillo SL, Subbian S, Chen B, Weisbrod TR, Jacobs WR Jr., Cirillo JD. Protection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from reactive oxygen species conferred by the mel2 locus impacts persistence and dissemination. Infection and immunity. 2009;77(6):2557–67. 10.1128/IAI.01481-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colangeli R, Haq A, Arcus VL, Summers E, Magliozzo RS, McBride A, et al. The multifunctional histone-like protein Lsr2 protects mycobacteria against reactive oxygen intermediates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(11):4414–8. 10.1073/pnas.0810126106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Voskuil MI, Bartek IL, Visconti K, Schoolnik GK. The response of mycobacterium tuberculosis to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Frontiers in microbiology. 2011;2:105 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kapopoulou A, Lew JM, Cole ST. The MycoBrowser portal: a comprehensive and manually annotated resource for mycobacterial genomes. Tuberculosis. 2011;91(1):8–13. 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lew JM, Kapopoulou A, Jones LM, Cole ST. TubercuList—10 years after. Tuberculosis. 2011;91(1):1–7. 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zahrt TC, Song J, Siple J, Deretic V. Mycobacterial FurA is a negative regulator of catalase-peroxidase gene katG. Molecular microbiology. 2001;39(5):1174–85. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodriguez GM, Voskuil MI, Gold B, Schoolnik GK, Smith I. ideR, An essential gene in mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of IdeR in iron-dependent gene expression, iron metabolism, and oxidative stress response. Infection and immunity. 2002;70(7):3371–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stallings CL, Stephanou NC, Chu L, Hochschild A, Nickels BE, Glickman MS. CarD is an essential regulator of rRNA transcription required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence. Cell. 2009;138(1):146–59. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Greenstein AE, MacGurn JA, Baer CE, Falick AM, Cox JS, Alber T. M. tuberculosis Ser/Thr protein kinase D phosphorylates an anti-anti-sigma factor homolog. PLoS pathogens. 2007;3(4):e49 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park ST, Kang CM, Husson RN. Regulation of the SigH stress response regulon by an essential protein kinase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(35):13105–10. 10.1073/pnas.0801143105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scherr N, Honnappa S, Kunz G, Mueller P, Jayachandran R, Winkler F, et al. Structural basis for the specific inhibition of protein kinase G, a virulence factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(29):12151–6. 10.1073/pnas.0702842104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saint-Joanis B, Souchon H, Wilming M, Johnsson K, Alzari PM, Cole ST. Use of site-directed mutagenesis to probe the structure, function and isoniazid activation of the catalase/peroxidase, KatG, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The Biochemical journal. 1999;338 (Pt 3):753–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knox R, Meadow PM, Worssam AR. The relationship between the catalase activity, hydrogen peroxide sensitivity, and isoniazid resistance of mycobacteria. American review of tuberculosis. 1956;73(5):726–34. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vilcheze C, Jacobs WR Jr. The mechanism of isoniazid killing: clarity through the scope of genetics. Annual review of microbiology. 2007;61:35–50. 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.111606.122346 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sherman DR, Mdluli K, Hickey MJ, Arain TM, Morris SL, Barry CE 3rd, et al. Compensatory ahpC gene expression in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1996;272(5268):1641–3. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bryk R, Lima CD, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Nathan C. Metabolic enzymes of mycobacteria linked to antioxidant defense by a thioredoxin-like protein. Science. 2002;295(5557):1073–7. 10.1126/science.1067798 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu Y, Coates AR. Acute and persistent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections depend on the thiol peroxidase TpX. PloS one. 2009;4(4):e5150 10.1371/journal.pone.0005150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li R, Yu C, Li Y, Lam TW, Yiu SM, Kristiansen K, et al. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1966–7. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nature methods. 2008;5(7):621–8. 10.1038/nmeth.1226 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wagner GP, Kin K, Lynch VJ. Measurement of mRNA abundance using RNA-seq data: RPKM measure is inconsistent among samples. Theory in biosciences = Theorie in den Biowissenschaften. 2012;131(4):281–5. 10.1007/s12064-012-0162-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Audic S, Claverie JM. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome research. 1997;7(10):986–95. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, et al. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41(Database issue):D808–15. 10.1093/nar/gks1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li X, Tao J, Han J, Hu X, Chen Y, Deng H, et al. The gain of hydrogen peroxide resistance benefits growth fitness in mycobacteria under stress. Protein & cell. 2014;5(3):182–5. 10.1007/s13238-014-0024-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson M, DeRisi J, Kristensen HH, Imboden P, Rane S, Brown PO, et al. Exploring drug-induced alterations in gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by microarray hybridization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(22):12833–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schnappinger D, Ehrt S, Voskuil MI, Liu Y, Mangan JA, Monahan IM, et al. Transcriptional Adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within Macrophages: Insights into the Phagosomal Environment. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;198(5):693–704. 10.1084/jem.20030846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Papavinasasundaram KG, Anderson C, Brooks PC, Thomas NA, Movahedzadeh F, Jenner PJ, et al. Slow induction of RecA by DNA damage in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology. 2001;147(Pt 12):3271–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Durbach SI, Andersen SJ, Mizrahi V. SOS induction in mycobacteria: analysis of the DNA-binding activity of a LexA-like repressor and its role in DNA damage induction of the recA gene from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Molecular microbiology. 1997;26(4):643–53. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boshoff HI, Reed MB, Barry CE 3rd, Mizrahi V. DnaE2 polymerase contributes to in vivo survival and the emergence of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell. 2003;113(2):183–93. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Warner DF, Ndwandwe DE, Abrahams GL, Kana BD, Machowski EE, Venclovas C, et al. Essential roles for imuA'- and imuB-encoded accessory factors in DnaE2-dependent mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(29):13093–8. 10.1073/pnas.1002614107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(Database issue):D199–205. 10.1093/nar/gkt1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Molecular microbiology. 2003;48(1):77–84. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(22):12989–94. 10.1073/pnas.2134250100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Timm J, Post FA, Bekker LG, Walther GB, Wainwright HC, Manganelli R, et al. Differential expression of iron-, carbon-, and oxygen-responsive mycobacterial genes in the lungs of chronically infected mice and tuberculosis patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(24):14321–6. 10.1073/pnas.2436197100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Venugopal A, Bryk R, Shi S, Rhee K, Rath P, Schnappinger D, et al. Virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis depends on lipoamide dehydrogenase, a member of three multienzyme complexes. Cell host & microbe. 2011;9(1):21–31. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grant CM. Regulation of translation by hydrogen peroxide. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;15(1):191–203. 10.1089/ars.2010.3699 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. DeMaio J, Zhang Y, Ko C, Young DB, Bishai WR. A stationary-phase stress-response sigma factor from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(7):2790–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Humpel A, Gebhard S, Cook GM, Berney M. The SigF regulon in Mycobacterium smegmatis reveals roles in adaptation to stationary phase, heat, and oxidative stress. Journal of bacteriology. 2010;192(10):2491–502. 10.1128/JB.00035-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Malhotra V, Okon BP, Clark-Curtiss JE. Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein kinase K enables growth adaptation through translation control. Journal of bacteriology. 2012;194(16):4184–96. 10.1128/JB.00585-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(JPG)

(DOC)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. The dataset of RNA-sequencing has been submitted to ArrayExpress under the accession number E-MTAB-3594.