Abstract

Introduction

Many factors alter gastrointestinal transit. Animal models are useful for preclinical studies of gastrointestinal transit, but terminal methods do not allow later study, and stressful assessment methods will likely alter the transit of the animal. To overcome these factors, we developed a new method to assay rat total gastrointestinal transit.

Methods

Standard plastic cages with their bottoms cut off were placed on wire mesh floors. Custom apparatuses were built to contain fecal pellets as they fell through the floors. Webcams connected to a computer running a security program were placed to image the pellets at regular intervals. Custom food was obtained with and without blue pigment. After habituating to the cages and the non-pigmented food, the pigmented food was administered. The duration to the appearance of the first pigmented pellet was determined by reviewing the photographs. This duration represents the complete gastrointestinal behavior, including feeding. We compared 24-hour fecal pellet counts using images to counts by visual inspection, and also made hourly counts. After establishing baseline transit times and hourly fecal pellet discharge, rats were given buprenorphine, known to alter gastrointestinal transit. Transit times and hourly discharge were obtained again and compared to the baselines.

Results

The methods were successful in determining transit times. Baseline measures were consistent between three groups of 8 rats. Visual and image-based counts were highly correlated. Transit times and hourly pellet discharge were reduced by buprenorphine.

Discussion

The described method offers a relatively simple, inexpensive, and non-invasive means to measure rat gastrointestinal behaviour. The method has potential for any studies where altered total gastrointestinal transit is an experimental concern.

Keywords: digestion, digestive diseases, gastrointestinal, methods, rat, transit time, constipation

Introduction

Many drugs, disease states, surgery, and aging alter gastrointestinal function, leading to increased or decreased transit in part of or in the entire gastrointestinal tract (Bauer, 2010; Mattei & Rombeau, 2006; Patel, et al., 2014; Siemens, Gaertner, & Becker, 2014; Smits & Lefebvre, 1996). In animal models, methods to measure gastrointestinal function include fecal pellet discharge counts, gastrointestinal emptying, gastrointestinal transit, and large intestinal transit, in vivo or ex vivo (Smits & Lefebvre, 1996; Wehner, et al., 2007; Yang, et al., 2014). None of these methods give an overall picture of the feeding and digestive behaviour of the animal. Moreover, many methods are terminal and otherwise stressful to the animal, which will alter the transit (Nakade, et al., 2007; Suda, Setoyama, Nanno, Matsumoto, & Kawai, 2013). We sought to develop a non-invasive method to determine overall gastrointestinal behaviour, from the initiation of eating to waste elimination.

Methods

The Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of New England approved all experiments. Three groups of 8 adult male Long Evans rats weighing 200–225g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Two groups were used for multiple trials, and the final weight of these rats was 300–350g. Apparatuses were designed to allow hands-free, 24 hour monitoring of fecal pellet discharge (Fig. 1A). The bottoms of standard plastic cages (47 cm X 26 cm X 21 cm, Allentown USA) were sawn off and the cages placed upon stainless steel wire mesh floors with ½″ openings. The openings allowed passage of fecal pellets, thus largely preventing coprophagy. These assemblies were placed on custom bases constructed of 6.35 mm clear acrylic sheet. Each base accommodated 2 cage-floor assemblies, and the sides were tapered to deflect fecal pellets towards the middle of the open base to help with visualization of the pellets. The entire assembly was placed upon a white absorbent paper sheet (VWR, USA). A 13 cm long X 10 cm diameter stout cardboard tube was placed in each cage for enrichment.

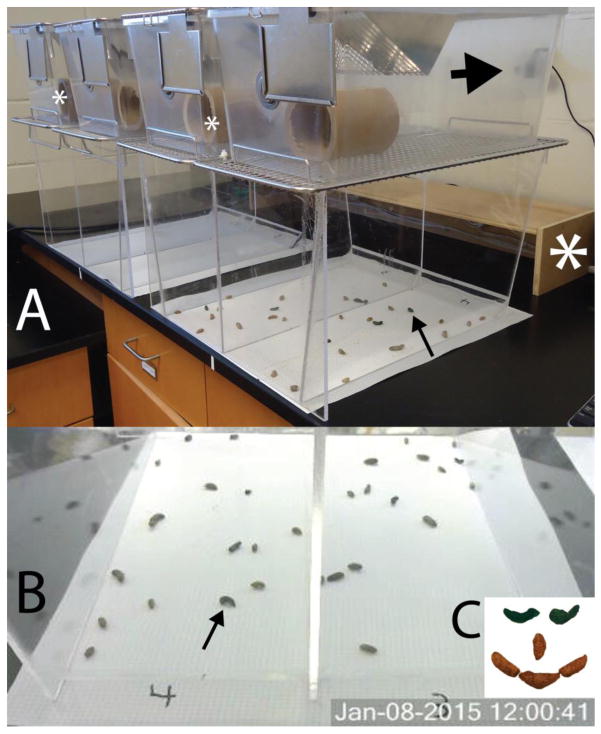

Figure 1.

A. Apparatus used to study transit time. In the closest collection area, there are 15 pellets, which also can be counted using the photograph (B), taken by the webcam (large arrow). The arrows point to the same blue fecal pellet. C. Blue pigmented pellets were readily discerned. Large white asterisk = box containing lights. Smaller white asterisks = light intensity measuring points.

A video surveillance program was installed on a PC (Security Monitor Pro, USA) and linked to 4 HD webcams (Logitech, USA) to monitor fecal pellet discharge. These cameras were installed to view the entire area under one assembly (Fig. 1B). The software allows constant monitoring or still shots to be taken at user-determined intervals. Because most feeding and defecation behaviour occurs at night, a low level light source was designed. Four 20W halogen lights were installed in an open 94 cm wide X 20 cm deep X 13 cm tall plywood box (Fig. 1A) that illuminated the pellet deposit area but prevented direct illumination of the rats. These lights were controlled by a timer that turned them on during the dark cycle of the room. The room lights were on from 07:00 – 19:00, providing 275–325 lux (normal lighting). The low-intensity lights were on from 19:00 – 07:00, providing 25–30 lux.

Purified custom diets with (TD.130861) or without (TD.94045) blue food coloring were obtained from Harlan (USA). We observed in preliminary studies that this color became clearly evident in the fecal pellets (Fig. 1C). We also observed in preliminary studies that rats readily ate the food, but ate somewhat less of it, which we attributed to the higher caloric content (data not shown). No information existed regarding accommodation to this diet, but our experience suggested that 3 days was sufficient for the rats to accept it, based upon their intake and pellet discharge (Fig. 2A–B).

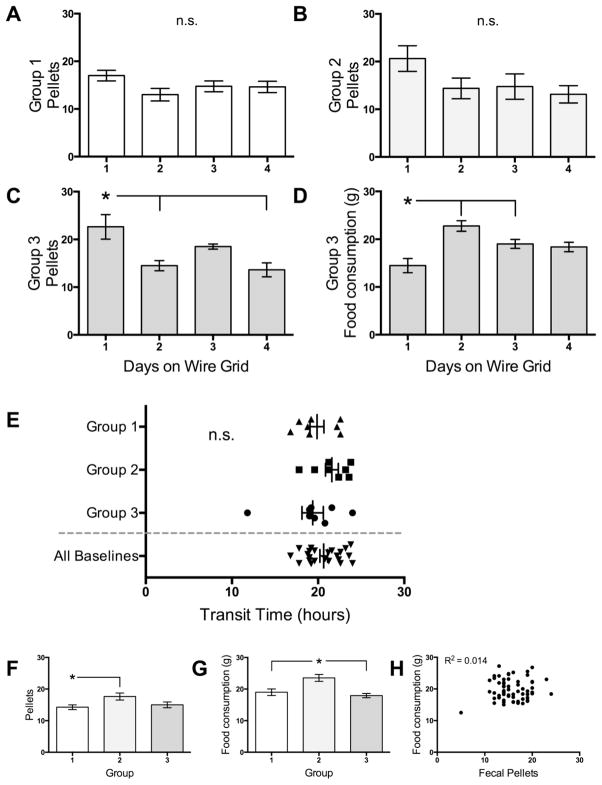

Figure 2.

Baseline data and accommodation to the apparatus. Data in all panels but F are expressed as means ± SEMs. A and B. Total daily fecal pellet discharge did not differ by day in the enclosure in Groups 1 and 2. C. Total daily fecal pellet discharge was higher for Group 3 unhandled rats on the first day in the apparatus, but stabilized. D. Daily food intake in Group 3 was lower the first day in the apparatus, but also stabilized. E. Baseline transit times were similar for all 3 groups. While there were significant differences between groups in daily fecal pellet counts (F) and food intake (G) taken during the same 24-hour epochs as the baseline transit times, these measures had no significant correlation (H). n.s. = not significant. * = significantly different from indicated groups.

Testing was performed using the following protocol. Rats in this study were taken from the animal facility and housed in a room with no other rats, 4 days prior to the measurements, to acclimate them to the custom diet and lighting conditions. Rats were individually placed in the custom enclosures, where they had free access to water and the non-colored custom diet. The paper was changed every 24 hours. After 3 days, transit time calculations were started. All experiments were started at 08:00. At this time, the white food was replaced with a weighed portion of blue food. The cameras were re-programmed to take images every 12 minutes. This interval was chosen to balance resolution with convenience (12 minutes = 0.2 hrs). After all rats expressed blue pellets, the experiment was stopped, and the rats were moved back to their normal cages within the animal facility. Consumption of blue food over 24 hours was measured.

Photographs and the white papers under the screens were reviewed and compared for the appearance of the first blue pellet. Transit time was recorded for each rat as the duration between introduction of blue food and observation of the first blue pellet. Pellets were visually counted daily, and compared to counts taken from photographs taken at the same time. Using the photographs, pellets were counted on an hourly basis for each animal.

Group 1 and Group 2 rats were handled for 3–4 minutes daily for 4 days prior to entering the study. They were then placed in the enclosures, and baseline transit times were obtained. Group 2 rats were tested during increased ambient temperature, and then retested, the second trial serving as their baseline. Group 3 rats were tested prior to and then after handling, the second trial serving as their baseline. After the trial with buprenorphine (see below) we tested if the time of day that the monitoring started affected the transit time by starting monitoring at 14:00 and comparing to the baseline of the same group.

In Group 3 we used buprenorphine, known to affect intestinal motility, as a practical application of this method. After establishing the baseline transit times, 1 dose of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg i.p.) was administered at 08:00. One week later, 3 doses of buprenorphine were administered, one at the beginning of the experiment, and then after 12 and 24 hours. The dose and interval of buprenorphine is midrange for what is commonly used for postoperative pain control (Kabadi, Kouya, Cohen, & Banik, 2015), and is considered to have an effective duration of action of 12 hours.

Data analysis and graphing was performed using Graphpad/Prism 6.0. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. All data sets were subjected to an omnibus normality test. Transit times were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests with Welch’s correction and F-tests for variance (to compare 2 measures in the same rats) or one-way ANOVAs with Tukey-Kramer post-hoc tests with Bartlett’s test for different variances (to compare multiple trials in the same rats). Unpaired t-tests were used because analysis reported that pairing was not effective, and repeated measure ANOVAs were not used because the analysis reported that matching was not effective. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (2-way) were calculated to compare daily visual counts to photographic counts, and daily fecal pellet discharge to food intake. Hourly pellet counts are graphically depicted, and were analyzed using a two-way repeated measure ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post-hoc tests. All data were subjected to variance testing. Power calculations were performed using Power & Sample Size Calculator (Statistical Solutions, USA). Statistical significance was set at 0.05 for all results.

Results

We report here the results of 8 trials in 3 groups of 8 rats. The appearance of the first blue pellet was readily observed in all cases, by comparing the image taken by the webcams to the direct visual inspection of the pellets. In all cases, the transition from brown to blue pellets was abrupt; about 1 in 8 rats would excrete 1 fecal pellet that was part brown and part blue. This transition indicated that it was unlikely that there was forward leaching of the pigment. The first blue pellets were often not as heavily pigmented as the later ones, which is likely due to the brown and blue chyme mixing in the cecum. We never observed brown pellets appearing after the blue-pigmented pellets appeared.

Figures 2A – D show parameters of acclimation to the apparatuses. Fecal pellet discharge did not differ by day for Groups 1 (F3, 28 = 2.0, ns; Bartlett’s statistic (BS) p = 0.97) or Group 2 (F3, 28 = 2.0, ns, BS p = 0.72), which were handled prior to testing (Fig. A and B). These data support that the rats acclimated to the enclosures readily. Fecal pellet discharge differed by day for Group 3 rats (F3, 28 = 6.7, p = 0.0015; BS p = 0.002), which were not handled prior to testing, with the difference driven by the increased first day on the grid (Fig. 2C). Food consumption was also significantly different by day for Group 3 (F3, 28 = 8.7, p = 0.0003; BS p = 0.63), with the change driven by the low initial day on the grid (Fig. 2D). These effects may reflect increased stress of accommodating to the apparatus for the unhandled rats. When all daily fecal pellet counts were analyzed together, the ANOVA was significant by day (F3, 28 = 3.0, p = 0.002; BS p = 0.003), with the only significant difference being the higher pellet discharge of Group 3 on day 1 (data not shown).

There were no significant differences between the transit times of the 3 groups (F3, 43 = 1.3, ns; BS p = 0.35; Table 1, Fig. 2E). There was 1 statistical outlier in the Group 3 baseline testing trial (Grubb’s method); although identified, this data point was left in all analyses.

TABLE 1.

Transit time descriptive statistics for all groups and trials (n = 8 all groups).

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Baseline | Baseline | High Ambient | Baseline | Unhandled | 1 Dose | 3 Dose | Time |

| Mean | 19.88 | 21.61 | 23.91 | 19.38 | 22.65 | 20.13 | 28.03 | 13.33 |

| SD | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 8.5 | 1.2 |

| SEM | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 3.0 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||||

| Median | 19.1 | 21.83 | 24.10 | 19.40 | 23.3 | 20.00 | 25.30 | 12.80 |

95%CI

|

17.97 | 19.85 | 22.51 | 16.44 | 21.03 | 18.07 | 20.90 | 12.30 |

95%CI

|

21.78 | 23.36 | 25.32 | 22.31 | 24.27 | 22.18 | 35.15 | 14.35 |

The 3 groups of rats were compared in terms of daily fecal pellet excretion and food intake on the day when their transit times were measured. Fecal pellet counts were significantly different by group (F2, 21 = 3.7, p = 0.043; BS p = 0.60), with the effect being driven by a lower number from Group 1 (Fig. 2F). Food intake was also statistically different between groups (F2, 21 = 9.8, p = 0.001; BS p = 0.49), with the effect being driven by higher consumption in Group 2 (Fig. 2G). These 2 parameters had poor correlation (Fig. 2H; R2 = 0.014, p = 0.35, n = 64; the first days in the enclosure and stressed days were excluded).

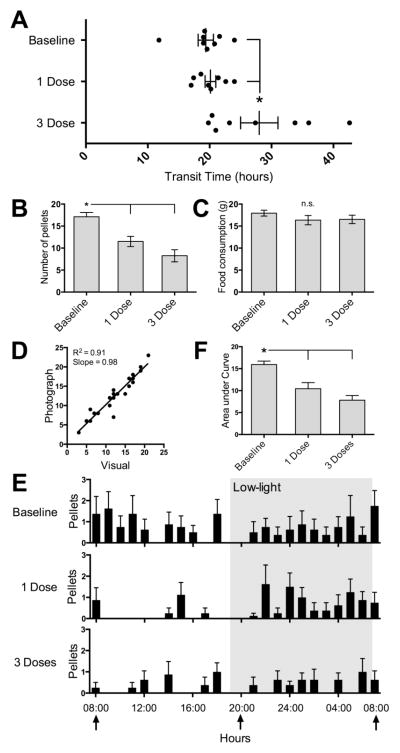

There was a significant affect of buprenorphine treatment in Group 3 (F2, 21 = 6.1, p = 0.008; BS p = 0.005; Fig. 3A). A single dose of 0.05 mg/kg buprenorphine did not increase the transit time, but 3 doses lengthened the transit time compared to Baseline and 1 Dose trials. Buprenorphine also affected fecal pellet discharge (F2, 21 = 14.6, p = 0.0001; BS p = 0.56; Fig 3B). Post-hoc tests revealed significant differences between Baseline and both 1 Dose and 3 Dose trials but not between 1 Dose and 3 Dose trials. Food consumption was not affected by buprenorphine administration (F2, 21 = 1.2, ns; BS p = 0.69; Fig 3C).

Figure 3.

Effect of buprenorphine in Group 3. Data in all but panel D are expressed as means ± SEMs. A. Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, 1 dose) did not affect transit times. Three equally spaced doses of buprenorphine had a profound effect on the transit times of some but not all rats. B. Both 1 dose and 3 doses of buprenorphine led to decreased total daily pellets compared to both other trials. C. There was no significant difference in food consumed in the 3 trials. D. Visual fecal pellet counts were highly correlated with counts made using the photographs alone. E. Hourly fecal pellet discharge for the 3 trials showed qualitative differences. Both 1 Dose and 3 Dose trials were significantly different from Baseline, but did not differ from each other (see text for details of ANOVA). F. The mean area under the curves differed by trial, with 1 Dose and 3 Dose trials being significantly different from Baseline but not from each other. * = significantly different from indicated groups.

To determine if the images were adequate to count total fecal discharge, we compared fecal pellet counts taken from direct visual inspection (Fig. 3B) to those taken from the photographs. The measures were highly correlated (R2 = 0.91, p < 0.0001, slope = 0.98, n = 24; Fig. 3D).

As the counting methods were highly correlated, we counted and then graphed the hourly pellet discharge using the images (Fig. 3E), and compared the entire 24-hour epochs of hourly discharge between groups. The analysis revealed a significant effect of time (F23, 161 = 1.7, p = 0.27) and dose (F2, 14 = 15.2, p = 0.0003), with no interaction of these parameters (F46, 322 = 0.9, p = 0.61). Post-hoc tests revealed significant differences between Baseline and both 1 Dose and 3 Dose trials but not between 1 Dose and 3 Dose trials. As an alternate method of analysis, we computed the area under the curve for each subject, and compared the means for each trial. This was significant for dose (F2, 21 = 14.1, p = 0.001; BS p = 0.35), with significant differences between Baseline and both 1 Dose and 3 Dose trials (Fig. 3F).

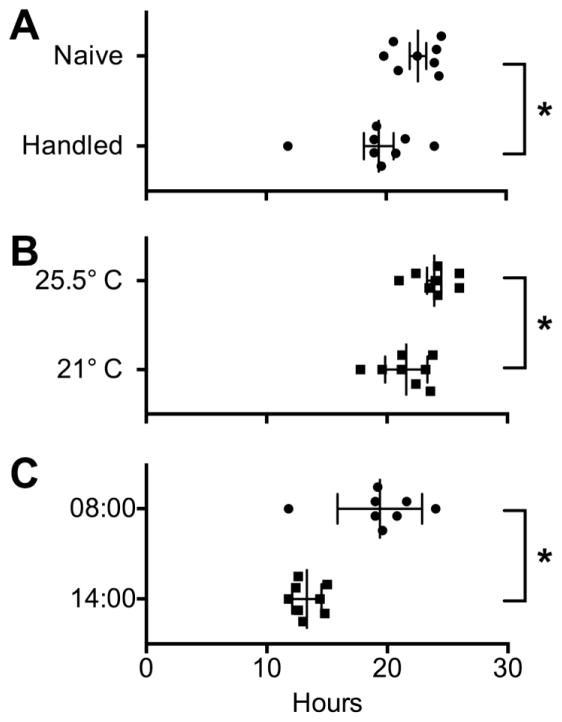

Because rats tend to be quite jumpy when first handled, and calm rapidly with proper handling, we tested Group 3 rats prior to and after handling. Figure 4A shows that handling decreased the transit time (t10.9 = 2.3, p < .04) to levels comparable with other baselines (Fig. 2E). We also observed that increased ambient temperature led to increased transit times (t13.4 = 2.4, p < .03; Fig 4B; this was a serendipitous error by our heating system).

Figure 4.

A. Transit times were longer prior to handling Group 3 rats. B. Higher ambient temperature led to longer transit times in Group 2 rats. C. The time of day led to different absolute transit times, with the later start time associated with less variability. See text for details. * = significant difference by t-test.

The hourly pellet discharge supported that the rat fecal pellet discharge was diurnal, with most of the activity occurring during dark hours, trailing off over the first few hours after the light cycle begins (Fig. 3E, top graph). To determine if the time of day that the measures started affected the transit time, we started a final trial with Group 3 at 14:00. The mean transit time was almost exactly 6 hours different from baseline (t8.7 = 4.6, p = .0014; Fig 4C), with a statistically lower variability (F test = p < 0.01).

We noted that if left on the wire cages after the blue food was removed and either unpigmented or normal chow was returned to the animals, the fecal pellets returned to normal pigmentation within 24–36 hours, at which time another test could be performed. We observed slower full clearance of the pigment when rats were immediately returned to their cages. This difference is likely due to consumption of some of the remaining blue fecal pellets that were subsequently being cleared from the gut.

A power analysis to detect a 2.5-hour difference was performed using the baseline transit time data for all 3 groups. Group 1 had a power of 0.87, Group 2 a power of 0.92, and Group 3 (with outlier removed) had a power of 0.97 (two-tailed tests). This supports that our group size of 8 was appropriate to lead to significance in relatively small mean differences.

Discussion

We have described a non-invasive and relatively low-cost means to obtain meaningful information about rat gastrointestinal function and behaviour. The interval between offering the food and the discharge of the first blue pellet represents the behavioural transit time. Moreover, it is possible to measure fecal pellet discharge at any desired interval. These methods could be used as an assay in any experiment where diseases or interventions interfere with gastrointestinal function, and where fecal pellet discharge can be used as an assay. Examples of such experiments include assays of drug side effects, such as shown in our data.

The method arose out of efforts to find a non-invasive and non-terminal method for evaluating gastrointestinal function as an assay for postoperative ileus and its role in postoperative adhesion formation. Because we needed the rats to survive their surgery for up to a month to evaluate their postoperative adhesions, we could not use terminal methods such as the charcoal, dextran, or radioactive meals, which require removal of the intestines.

The main limitation of our method was the relatively low resolution of the camera (720p). For transit times, the color difference was hard to discern, although this was easier during low light periods. However, the using the pattern of the pellets as seen visually, it was easy to identify in the photographs when the first pellet appeared. The accuracy of the photographic counting took practice to develop, and there are a number of factors that we identified that could lead to discrepancies, the main being the resolution. Additionally, segmented fecal pellets, and pellets very close together, could possibly be counted as two when viewed directly, while they may be counted as one when viewed from the opposite perspective and at a fixed angle as seen by the camera. Also, paper shreds from the cardboard occasionally occluded full visualization of pellets from the aspect angle of the webcam. Higher counts could also be possible if food particles that fell into the collection area resembled pellets, especially if further away from the camera. However, as the data show, these differences did not impact the data set presented.

Another factor that should be considered is that once monitoring is started the transit time will be affected by the diurnal rhythm, unless it is altered by the treatment. In our results, the Group 3, 3 Dose trial extended beyond when the normal rats would have substantive gastrointestinal activity (beyond ~12:00). This may have had the effect of extending the transit time in rats that had been otherwise delayed. This trial also had the only non-normal distribution of transit times.

Our first efforts to evaluate total transit time had multiple problems, and their discussion may inform future efforts. Initially, we hypothesized that sifting the fecal pellets from wood chip bedding at regular intervals following feeding the rats blue food would allow a good estimate of transit time, using the ratio of blue pellets to total pellets. We learned a number of things in multiple experiments. 1. The expression of fecal pellets is anything but regular, and is highly diurnal (as confirmed in Fig. 3E). This suggests that transit time estimation based on daily output can be predicted to be an insensitive measure. Our observations also support that studies started and finished during normal daytime hours may not have strong predictive power since the number of fecal pellets discharged during this period or any sub-epoch will be low. 2. Rats are known to eat their feces (Ebino, 1993), and we estimated that the rate is approximately 20%. Importantly, we observed that coprophagy is increased sharply with administration of buprenorphine (as it was with morphine in preliminary experiments). In one preliminary experiment using the same apparatus we observed a total lack of brown pellets 24 hours following administration of one 3 mg/kg dose of morphine. The only explanation for this observation is that the rats consumed all of the brown pellets that were in their system, which had to precede the blue pellets. We regularly observed them turning to immediately grasp and then consume a pellet, which has been previously reported (Ebino, 1993). 3. We also tried custom food with an orange pigment, but it did not show up in the pellets. 4. In preliminary experiments we noted that other environmental changes than reported above affected the daily total pellet count. In our animal facility with mixed gender rats, we noted a sharp decline of total fecal pellets from female rats following the arrival of adult male rats. Additionally, we observed that moving the same rats to our laboratory and accidentally leaving the usual room lights on overnight decreased total fecal pellet discharge. Combined with the presented data on temperature and handling, these observations support that fecal pellet discharge is part of a highly complex and sensitive system, and that environmental control is important in such studies.

Our data also support that the time of day that the monitoring starts is important to keep constant, and suggests that starting later in the day may lead to reduced variability and thus higher precision. In studies where lengthy procedures will be performed on multiple rats, is seems prudent to start the monitoring within a short window, although that window may have to be determined for each lab. A future study could determine if transit times were correlated with the time that the rats first eat the blue food, rather than being presented with it. Or, it might be reasonable when doing multiple surgeries to withhold food for a few hours and present the blue food at the same time for all rats.

In conclusion, we have presented a novel method for evaluating total gastrointestinal transit. Our data support that this is a true behavior, being sensitive to environmental factors. The ability to count fecal pellet discharge with any time resolution desired could be adapted to shorter-term studies. The method should prove useful in pharmacological and other studies where gastrointestinal transit is an outcome measure, especially those that are sensitive to acute stressors that may accompany and confound other methods.

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01GM108041 supported the research reported in this manuscript. Susan Chapelle is thanked for many discussions that contributed to the development of this method, and Anthony Pastore and Holly Beaulac are thanked for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bauer AJ. Two immune arms to stop one gut. Nature Medicine. 2010;16:1378–1379. doi: 10.1038/nm1210-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebino KY. Studies on coprophagy in experimental animals. Jikken Dobutsu. 1993;42:1–9. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.42.1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabadi R, Kouya F, Cohen HW, Banik RK. Spontaneous pain-like behaviors are more sensitive to morphine and buprenorphine than mechanically evoked behaviors in a rat model of acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:472–478. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattei P, Rombeau JL. Review of the pathophysiology and management of postoperative ileus. World J Surg. 2006;30:1382–1391. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakade Y, Fukuda H, Iwa M, Tsukamoto K, Yanagi H, Yamamura T, Mantyh C, Pappas TN, Takahashi T. Restraint stress stimulates colonic motility via central corticotropin-releasing factor and peripheral 5-HT3 receptors in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1037–1044. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00419.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel BA, Patel N, Fidalgo S, Wang C, Ranson RN, Saffrey MJ, Yeoman MS. Impaired colonic motility and reduction in tachykinin signalling in the aged mouse. Exp Gerontol. 2014;53:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemens W, Gaertner J, Becker G. Advances in pharmacotherapy for opioid-induced constipation - a systematic review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014:1–18. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.995625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits GJ, Lefebvre RA. Influence of aging on gastric emptying of liquids, small intestine transit, and fecal output in rats. Exp Gerontol. 1996;31:589–596. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(96)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda K, Setoyama H, Nanno M, Matsumoto S, Kawai M. Involvement of parasympathetic pelvic efferent pathway in psychological stress-induced defecation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1200–1209. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i8.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner S, Behrendt FF, Lyutenski BN, Lysson M, Bauer AJ, Hirner A, Kalff JC. Inhibition of macrophage function prevents intestinal inflammation and postoperative ileus in rodents. Gut. 2007;56:176–185. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.089615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Xi TF, Li YX, Wang HH, Qin Y, Zhang JP, Cai WT, Huang MT, Shen JQ, Fan XM, Shi XZ, Xie DP. Oxytocin decreases colonic motility of cold water stressed rats via oxytocin receptors. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10886–10894. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]