Abstract

Background

Pregnancy is an opportune time to initiate diabetes prevention strategies for minority and underserved women, using culturally tailored interventions delivered by community health workers (CHWs). A community-partnered randomized controlled trial (RCT) with pregnant Latina women resulted in significantly improved vegetable, fiber, added sugar, and total fat consumption compared to a minimal intervention (MI) group. However, studying RCT intervention effects alone does not explain the mechanisms by which the intervention was successful or help identify which participants may have benefitted most.

Purpose

To improve the development and targeting of future CHW interventions for high-risk pregnant women, we examined baseline characteristics (moderators) and potential mechanisms (mediators) associated with these dietary changes.

Methods

Secondary analysis of data for 220 Latina RCT participants was conducted. A linear regression with effects for intervention group, moderator, and interaction between intervention group and moderator was used to test each hypothesized moderator of dietary changes. Sobel-Goodman mediation test was used to assess mediating effects on dietary outcomes.

Results

Results varied by dietary outcome. Improvements in vegetable consumption were greatest for women who reported high spousal support at baseline. Women younger than age 30 were more likely to reduce added sugar consumption than older women. Participants who reported higher baseline perceived control were more likely to reduce fat consumption. No examined mediators were significantly associated with intervention effects.

Conclusion

Future interventions with pregnant Latinas may benefit from tailoring dietary goals, to consider age, level of spousal support, and perceived control to eat healthy.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes (GDM) disproportionately affect African Americans, Native Americans, and Latinos of lower socio-economic status in the United States (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). Latina women are at increased risk for GDM, and women with a history of GDM are at 8-fold increased risk of progressing to type 2 diabetes (Chodick et al., 2010). Pregnancy is an especially opportune time for preventive interventions as weight gain and retention of weight after pregnancy may predict future risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes (Kieffer, 2000; van der Pligt et al., 2013). Furthermore, the period of pregnancy and postpartum may be a time when women are especially motivated to initiate healthy behavioral changes (Kieffer, 2000; Ostbye et al., 2009).

Developing and implementing effective prevention strategies to reduce the risk of progression to diabetes among high-risk populations is a national priority (Eyre, Kahn, Robertson, & Committee, 2004). Culturally tailored interventions delivered by community health workers (CHWs) are effective in improving diabetes related risk factors in medically underserved, ethnic minority populations (Jackson, 2009; Katula et al., 2013; Ruggiero, Castillo, Quinn, & Hochwert, 2012; Valen, Narayan, & Wedeking, 2012). Few such studies have focused specifically on pregnant Latina women (Kieffer et al., 2014).

Healthy Mothers on the Move (Healthy MOMs) was a community-academic partnered randomized controlled trial (RCT) that examined whether a CHW-led intervention could reduce risk factors for GDM and type 2 diabetes among pregnant and postpartum Latina participants compared to a minimal intervention (MI) control group. The Healthy MOMs study results showed improved dietary behaviors at follow-up among pregnant women in the CHW intervention arm, compared to the MI arm (Kieffer et al., 2014). However, studying RCT intervention effects alone does not explain the mechanisms by which the intervention was successful or help identify which participants may have benefitted most (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). Analyses that elucidate moderators and mediators of RCTs provide an important next step to guide clinical interpretation of trials and inform the design and targeting of future interventions (Kraemer et al., 2002).

Moderators of an intervention are “pre-randomized” baseline characteristics, uncorrelated with the treatment, and may show an interactive effect with the outcome (Kraemer et al., 2002). For example, Rosland et al. have previously shown that baseline family support improves diabetes self-management (Rosland et al., 2008). Similarly, baseline family support for a healthy diet could have moderated the effects of this CHW-led intervention. Identifying characteristics of participants that lead to improved outcomes may help inform the design and targeting of future interventions. Mediators identify mechanisms through which an intervention may have achieved an effect (Kraemer et al., 2002). For example, specific features of the Healthy MOMs intervention such as changes in dietary beliefs were possible mediators of positive intervention effects.

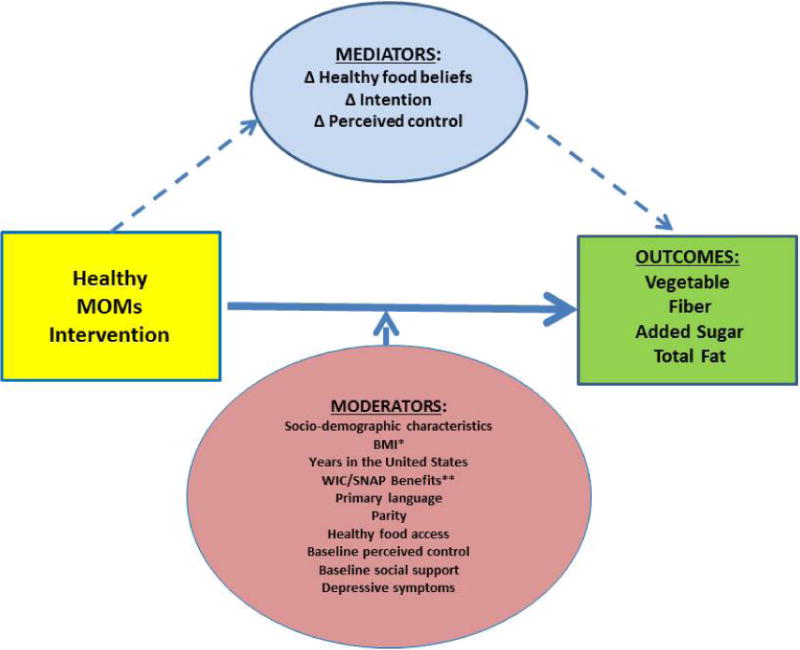

The aim of this study is to examine potential moderators and mediators of the intervention’s effects on dietary behaviors, building on the original conceptual model that informed the design of Healthy MOMs. Potential moderators of intervention effects included in the conceptual model were a priori hypothesized, based on previous work in this community, previous literature, and clinical relevance, to include baseline measures of participants’ age, primary language, social support, body mass index (BMI), perceived control, reported healthy food access, parity, years in the United States (US), depressive symptoms, and receiving Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infant and Children (WIC) or Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. In addition, the conceptual model for this study [see Figure 1] hypothesizes that improvements in dietary outcomes achieved through the CHW intervention were mediated by improvements in three key theory of planned behavior (TPB) variables: 1) participants’ intention to eat healthy; 2) perceived control to make healthy dietary choices; and 3) food beliefs related to healthy pregnancy (Ajzen, 1991; Godin & Kok, 1996; Montaño, Danuta, & Taplin, 1997).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for Mediators and Moderators of the Healthy MOMs Intervention

*BMI-Body Mass Index

**WIC/SNAP Benefits-Whether participant received the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infant and Children (WIC) or Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits

Methods

The Healthy MOMs study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan, and all participants signed written informed consent. Setting, recruitment, intervention, data collection, outcome measurement, and analytic methods are described in detail elsewhere (Kieffer, Caldwell, et al., 2013; Kieffer et al., 2014).

Interventions

Two models of interpersonal and health behavior, the TPB and social support theory, guided development of the Healthy MOMs healthy lifestyle intervention. The TPB postulates that an individual’s intention and ability to perform a behavior help to determine performance of a behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Godin & Kok, 1996; Montaño et al., 1997). Intention, in turn, is determined by individuals’ attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. In accordance with the TPB model, the context and perspectives about diet, physical activity and weight related beliefs, barriers and strategies of Latinas in southwest Detroit were elicited during formative research conducted in the same community and used to create the Healthy MOMs survey and to inform the intervention design, materials, and methods (Kieffer, Salabarría-Peña, et al., 2013). The Healthy MOMs intervention focused primarily on influencing behavioral beliefs by providing information and support aimed at affirming and reinforcing healthful dietary beliefs and practices and providing healthier alternatives for less healthy dietary behaviors. It encouraged developing knowledge and skills to increase women’s intention and ability to eat healthfully within the cultural, social, and physical environment of their Detroit community.

The Healthy MOMs formative research also emphasized the importance of social support for pregnant Latinas’ dietary behavior (Thornton et al., 2006). Social support theory assumes that interactions with other individuals will have an impact on individuals’ health-related behavior change, including diet and exercise (Bruhn, 1991; Kelsey et al., 1996; Sallis, Grossman, Pinski, Patterson, & Nader, 1987). Social support has been linked to behavioral control, subjective norms, attitudes, and behavioral beliefs identified in the TPB (Langford, Bowsher, Maloney, & Lillis, 1997). Thus, the Healthy MOMs CHW intervention was designed to provide social support from the CHWs and other intervention group participants for improving targeted dietary behaviors.

The intervention was conducted in southwest Detroit community organization meeting rooms between 2004 and 2006 in Spanish by trained Latina CHWs. It included Healthy MOMs general pregnancy education and a specific curriculum and activities designed to educate and empower women to address barriers to healthier lifestyles (Thornton et al., 2006). The curriculum was conducted during two home visits and nine group meetings during 11 consecutive weeks. Nine concurrent group “activity day” meetings were also available for Healthy MOMs participants. The MI group received the Healthy MOMs pregnancy education curriculum during three group meetings conducted by a health professional from a community health agency as well as March of Dimes and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) resources on healthy eating and exercise in Spanish. Participants in both groups received the same incentives for participation. In depth descriptions of the interventions are reported elsewhere (Kieffer et al., 2014).

Healthy MOMs Sample Recruitment and Data Collection

Pregnant Latinas were recruited at a federally qualified health center (FQHC), a WIC clinic, and local community organizations in southwest Detroit, Michigan. Of recruited women, 278 were randomized to the trial; 139 to each intervention arm (Kieffer et al., 2014). Three women in the MI arm did not complete baseline or follow up food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), and 55 women were missing either baseline or follow up questionnaires. The current study focused on the 220 women who completed baseline and follow up surveys and FFQs. Due to missing or incomplete responses to some questions, the participants included for the analyses ranged from 212 to 220. Sociodemographic and dietary data were collected at baseline (mean [SD]= 18.6 [4.5] weeks of gestation) and follow-up (mean [SD]= 29.2 [4.8] weeks of gestation). Food intake was collected using an FFQ validated in a Hispanic population (Kristal, Feng, Coates, Oberman, & George, 1997). At baseline, women were asked about their dietary habits in the past year. At follow up, they were asked about their dietary habits in the past 3 months.

Outcome Measures

Outcomes included in the analysis were reported dietary intake of added sugar (grams), total fat (grams), fiber (grams), and vegetable (servings), as these outcomes were significantly improved in the CHW intervention arm. Compared to the MI group, the Healthy Moms group had a 16.1% greater decrease in added sugar consumption; a 12.9% greater decrease in total fat consumption, and 41.9% and 15.9% greater improvements in vegetable and fiber consumption, respectively. The full set of outcomes is reported elsewhere (Kieffer et al., 2014).

Moderators

Variables hypothesized to change the intervention effect were all measured at baseline for the entire study population (n=220) and are listed in Table 1. To assess support from spouse, family, and friends, the following question was asked, “How often has your Husband or Partner/Mother/Friend or Others encouraged you to eat more fruits and vegetables/eat foods with less fat/eat foods and drink beverages with less sugar/eat more fiber”, on a 1 to 5 scale, from “Never” to “Always”. Baseline perceived control was similarly addressed on a “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree” scale with the following question, “I can easily eat more fruits and vegetables/eat foods with less fat/eat foods and drink beverages with less sugar/eat more fiber”. Depression was measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) (Kieffer, Caldwell, et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Hypothesized Moderators of the Healthy MOMs Intervention

| MOMs Group | Minimal Intervention Group (Control) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Moderators | n | mean or % | n | mean or % | p-value |

| Age, years (mean) | 139 | 27.3 | 138 | 27.1 | 0.72 |

| Ethnicity, % Mexican/Chicano | 139 | 93.0 | 137 | 90.0 | 0.37 |

| Education, years, (mean) | 139 | 9.1 | 136 | 9.4 | 0.40 |

| Occupation, % homemaker | 138 | 91.0 | 133 | 90.0 | 0.92 |

| Marital Status, % | 137 | 133 | 0.78 | ||

| Never married | 47 | 34.3 | 50 | 37.6 | |

| Married | 84 | 61.3 | 76 | 57.1 | |

| Separated/Divorced | 6 | 4.4 | 7 | 5.3 | |

| Years lived in the US, (mean) | 138 | 6.6 | 132 | 6.6 | 0.99 |

| Received SNAP* in last 6 months, % | 137 | 20.0 | 133 | 23.0 | 0.55 |

| Mother received WIC** services in last 6 months, % | 137 | 81.8 | 133 | 75.9 | 0.24 |

| Spanish speaking only, % | 139 | 84.9 | 137 | 75.2 | 0.04 |

| BMI, % | 129 | 123 | 0.64 | ||

| Normal weight | 79 | 61.2 | 70 | 56.9 | |

| Overweight | 29 | 22.5 | 34 | 27.6 | |

| Obese | 21 | 16.3 | 19 | 15.5 | |

| Parity, (mean) | 139 | 1.5 | 137 | 1.4 | 0.64 |

| Healthy food access, (mean) | 138 | 3.9 | 133 | 3.6 | 0.21 |

| Baseline perceived control, (mean) | |||||

| Vegetable | 138 | 4.3 | 133 | 4.3 | 0.60 |

| Fiber | 138 | 4.3 | 133 | 4.2 | 0.63 |

| Added sugar | 138 | 3.7 | 133 | 3.8 | 0.48 |

| Total fat | 138 | 2.8 | 133 | 3.2 | 0.03 |

| Baseline spouse encouragement to eat healthy, (mean) | |||||

| Vegetable | 132 | 3.1 | 126 | 3.1 | 0.52 |

| Fiber | 131 | 2.6 | 126 | 2.5 | 0.57 |

| Added sugar | 130 | 3.1 | 126 | 3.2 | 0.98 |

| Total fat | 130 | 3.6 | 126 | 3.3 | 0.16 |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D*** scale score), (mean) | 137 | 13.3 | 132 | 12.9 | 0.65 |

SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits)

WIC (The special supplemental nutrition program for Women, Infant, and Children)

CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies 20-item depression scale)

Note: All self-reported scales have a range of 1–5 with more positive outcomes reflected by higher numbers (e.g. for healthy food access, baseline perceived control and spousal support to eat vegetables/fiber/less added sugar/less total fat, postive outcomes are reflected by scores closer to 5). P-values indicate differences between groups. P-values for marital status, BMI, and ethnicity are from Pearson’s chi-square statistics for categorical variables. Other p-values are from t-tests.

Mediators

For the current study, changes from baseline to follow up in self-reported intention to eat healthy, healthy food beliefs, and perceived control to make healthy food choices among all 220 women were examined [See Supplement 1 for survey questions and Table 2 for summary statistics]. These mediators were assessed through survey questions designed specifically for each target behavior and derived from the formative research in accordance with the TPB (Ajzen, 1991; Kieffer, Salabarría-Peña, et al., 2013; Povey, Conner, Sparks, James, & Shepherd, 2000). Participants were asked to rate their agreement with various statements that assess intention, beliefs, and perceived control to eat each targeted food category (i.e. vegetables, fiber, added sugar, and fat) on a 1 to 5 scale, from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree”. Some of the items were reverse coded so that the higher number corresponded to the more positive outcome. Only participants with baseline and follow up data were included in the analysis.

Table 2.

Hypothesized Mediators of the Healthy MOMs Intervention

| MOMs Group | Minimal Intervention Group (Control) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mediators | n | mean | n | mean | p-value |

| Healthy food beliefs about Vegetables | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.8 | 132 | 4.7 | 0.85 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.9 | 120 | 4.8 | 0.01 |

| Change | 115 | 0.1 | 114 | 0.1 | 0.15 |

| Healthy food beliefs about Fiber | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.5 | 131 | 4.6 | 0.73 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.9 | 119 | 4.6 | 0.02 |

| Change | 115 | 0.4 | 114 | 0.0 | 0.13 |

| Healthy food beliefs about Added Sugar | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 2.4 | 131 | 2.6 | 0.38 |

| Follow up | 116 | 2.6 | 120 | 2.9 | 0.14 |

| Change | 115 | 0.4 | 114 | 0.3 | 0.79 |

| Healthy food beliefs about Total Fat | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.4 | 132 | 4.5 | 0.50 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.7 | 119 | 4.3 | 0.002 |

| Change | 115 | 0.3 | 114 | 0.2 | 0.006 |

|

| |||||

| Intention to eat Vegetables | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.5 | 133 | 4.6 | 0.44 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.8 | 120 | 4.5 | 0.02 |

| Change | 115 | 0.3 | 115 | 0.1 | 0.02 |

| Intention to eat Fiber | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.4 | 133 | 4.5 | 0.76 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.8 | 120 | 4.4 | 0.00 |

| Change | 115 | 0.4 | 115 | 0.1 | <.001 |

| Intention to reduce Added Sugar | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.4 | 133 | 4.2 | 0.12 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.8 | 120 | 4.4 | <.001 |

| Change | 115 | 0.4 | 115 | 0.2 | 0.32 |

| Intention to reduce Total Fat | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.4 | 133 | 4.4 | 0.77 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.8 | 119 | 4.4 | <.001 |

| Change | 115 | 0.4 | 114 | 0.0 | .003 |

|

| |||||

| Perceived control to eat Vegetables | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.3 | 133 | 4.3 | 0.60 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.5 | 120 | 4.4 | 0.19 |

| Change | 115 | 0.2 | 115 | 0.1 | 0.24 |

| Perceived control to eat Fiber | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 4.3 | 133 | 4.2 | 0.63 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.6 | 120 | 4.3 | 0.001 |

| Change | 115 | 0.3 | 115 | 0.1 | .07 |

| Perceived control to reduce Added Sugar | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 3.7 | 133 | 3.8 | 0.48 |

| Follow up | 116 | 4.2 | 119 | 4.1 | 0.31 |

| Change | 115 | 0.5 | 114 | 0.3 | 0.32 |

| Perceived control to reduce Total Fat | |||||

| Baseline | 138 | 2.8 | 133 | 3.2 | 0.03 |

| Follow up | 116 | 3.1 | 120 | 3.2 | 0.79 |

| Change | 115 | 0.3 | 115 | 0.0 | .25 |

Only measured at follow up

Note: All self-reported scales have a range of 1–5 with more positive outcomes reflected by higher numbers (e.g. healthier food beliefs and more perceived control to make healthy choices about vegetables/fiber/added sugar/total fat are reflected by outcomes closer to 5). P-values indicate difference between treatment groups. P-values are from t-tests.

Analysis

Two-sided tests and an overall significance level of p=0.05 for outcomes were used to assess differences. In the summary of moderators and mediators, continuous variables were compared using t-tests. We used Pearson’s chi-square statistics to assess the independence of two binary/categorical variables [See Table 1 and 2].

To identify possible moderators, we assessed variations in the intervention effects by each of the examined moderating variables [Table 1], using a linear regression model with effects for intervention group, moderator, and interaction between intervention group and moderator. We included a covariate of each outcome measured at baseline for all regressions. For the model that examined age as a moderator, parity was also included as a potential confounder.

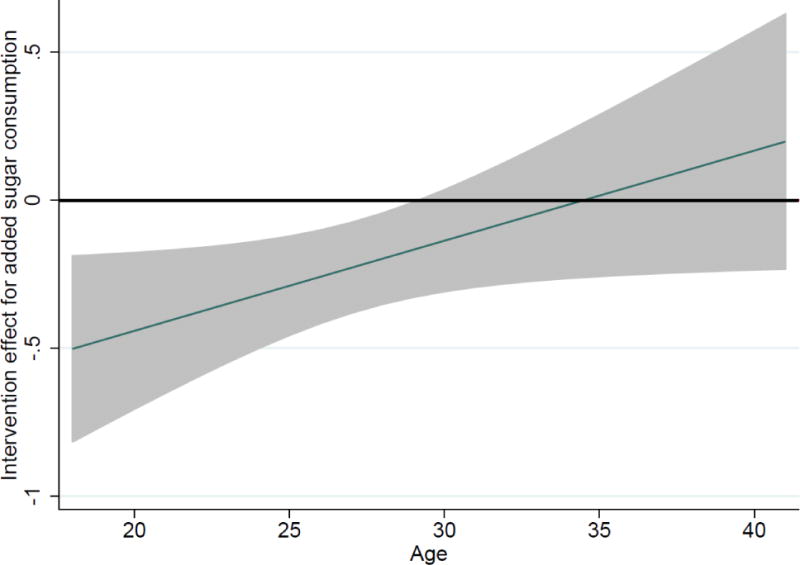

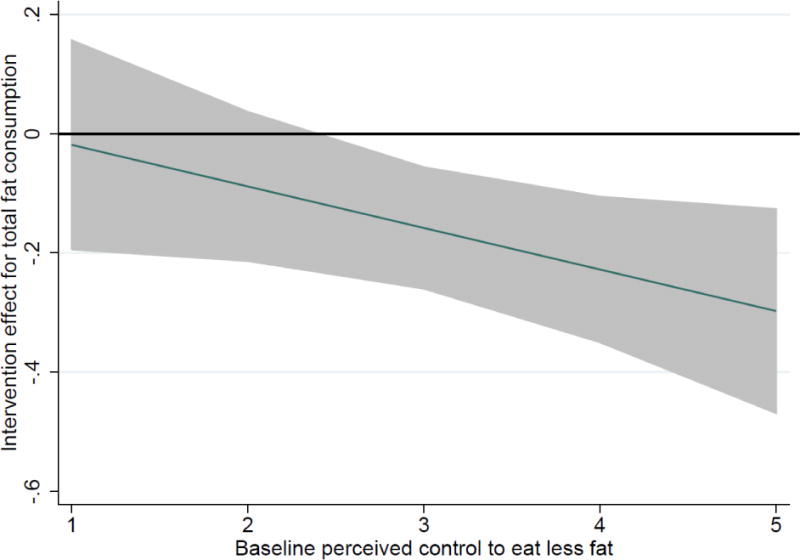

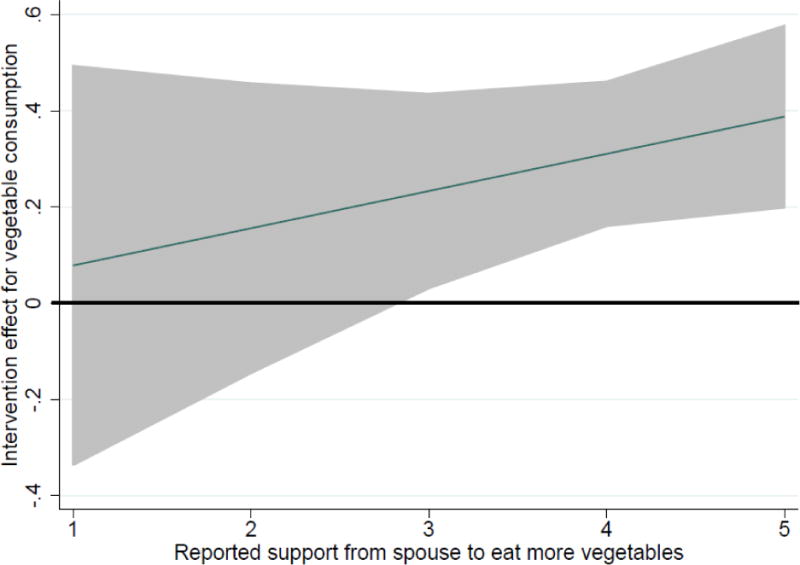

Multivariate fractional polynomial interaction (MFPI) was used to evaluate linear and high degrees of fractional polynomial functional forms for the significant interactions, and the linear interaction model was the best fit for all the significant moderators (Royston & Sauerbrei, 2008, 2009). Variations in intervention effects across levels for each significant moderator are presented graphically using two-way plots, including 95% confidence intervals, calculated using the delta method in STATA, version 12 [See Figures 2–4].

Figure 2.

Variation in intervention effect for added sugar consumption by age

Lower age associated with significant reduction in added sugar consumption. Grey bands indicate 95% confidence intervals. Interaction term: 03; p<.05, n= 218

Figure 4.

Variation in intervention effect for total fat consumption by baseline perceived control to eat less fat

Lower values on perceived control scale indicate less confidence by participant to eat less fat. Grey bands indicate 95% confidence intervals. Interaction term: −.07; p<.05, n= 215

We also conducted moderator analyses by dichotomizing moderator variables (age<30 vs. age>=30; spousal support <=3 vs. spousal support >3; baseline perceived control <=3 vs. baseline perceived control >3, and assessed intervention effects within each subgroup (e.g., age<30) and compared it between groups (e.g., age<30 and age>=30). We were adequately powered at 0.8 to detect intervention effects within each subgroup.

We employed the Sobel-Goodman mediation test to assess whether intervention effects were mediated by the potential mediating variables (Table 2). We examined each mediator separately and then multiple mediators together (Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Sample

Participants had a mean age of 27, median of 1 previous pregnancy, and mean BMI of 24.5 at baseline. Most women were Mexican/Chicano (91%) and Spanish speaking only (80%). All measured baseline characteristics were not different for women included in the current analyses compared to those who were excluded due to incomplete data (Kieffer et al., 2014).

Table 1 lists descriptive statistics for moderators. For most moderators, there was no difference between the MI group and the Healthy MOMs group, except the number of women who were Spanish speaking only and self-reported baseline perceived control to eat less fat. Table 2 lists descriptive statistics for the hypothesized mediators from our conceptual model. Higher scores indicate positive outcomes. Most of the hypothesized mediators had high baseline scores of > 4 on the scale of 1–5.

Moderator Effects

Moderator analysis showed that the intervention effect for added sugar consumption was statistically significant for the younger participants but not for the older participants [see Figure 2]. Added sugar consumption was reduced by 31% for younger women (ages 18–29) (p<.01; 95% CI: −51%, −12%). In addition, baseline spousal support to eat fruits and vegetables moderated the intervention effect for consumption of vegetables (interaction term: 31, p<0.05; 95% CI: 003, 61) [See Figure 3]. An increase of 47% in vegetable consumption was seen for women who reported greater baseline support from their spouse to eat more vegetables (p<.05; 95% CI: 25%, 68%). Lastly, self-reported perceived control to eat less fat moderated the intervention effect for total fat consumption (interaction term: −.07, p<.05; 95% CI: −.14, −.0001) [See Figure 4]. Significant decreases in total fat consumption were seen for those women who reported higher levels (i.e., 3 or greater) of perceived control to eat less fat compared to the MI group (−25%, p<.01; 95% CI: −41%, −10%).

Figure 3.

Variation intervention effect for vegetable consumption by spousal support

Lower reported support values indicate less baseline support from spouse. Grey bands indicate 95% confidence intervals. Interaction term: 11; p=.14 [for dichotomized outcome of low versus high support, interaction term: 31; p<.05], n= 208

Mediator Effects

None of the hypothesized mediators (self-reported dietary outcome-specific intention to eat healthy, healthy food beliefs and perceived control to make healthy food choices) were significantly associated with any of the improved dietary outcomes from baseline to follow up.

Discussion

The Healthy MOMs intervention was an innovative CHW-led intervention that improved several key dietary behaviors among low income pregnant Latinas (Kieffer et al., 2014). By testing mediators and moderators of intervention effectiveness, this study sought to address gaps in the literature by elucidating who might benefit most from similar programs as Healthy MOMs and through what mechanisms the intervention was effective.

Among the hypothesized moderators, age, spousal support, and baseline perceived control moderated some intervention effects. Younger women reported greater post-intervention improvement in added sugar consumption compared with older women. Women with high levels of baseline self-reported spousal support significantly increased their vegetable consumption, and the intervention had a larger effect on improving self-reported fat consumption for those women who reported high levels of perceived control to eat less fat at baseline. These moderating effects varied by type of dietary behavior. Thus, increasing women’s consumption of healthy foods may require different behavior change strategies than reducing consumption of less healthy dietary components. Lapointe et al. compared a restrictive message, low fat diet to a nonrestrictive message, high vegetable-moderate fruit consumption diet and found significantly greater increases in vegetable and fruit consumption in the nonrestrictive message group. This study suggests that tailoring interventions to specific dietary goals and behaviors may be more effective (Ello-Martin, Roe, Ledikwe, Beach, & Rolls, 2007; Epstein et al., 2001; Lapointe et al., 2010).

Pregnant Latina women who reported high levels of baseline spousal support had greater improvement in vegetable consumption. This study’s findings are consistent with the importance of husband support on dietary practices found in earlier formative research conducted with pregnant Latinas in the same community (Thornton et al., 2006). Similarly, in a study in a Latino community in Salinas Valley, California, Harley et al. found that, among pregnant women who immigrated to the US in childhood, higher levels of social support from the father of the baby were associated with higher quality diets (Harley & Eskenazi, 2006). A study of older Mexican-Americans with diabetes, found that higher levels of perceived family support at baseline correlated with higher levels of improved diet and exercise (L. K. Wen, M. D. Shepherd, & M. L. Parchman, 2004).

This study found that younger women showed significantly greater improvement in reduction of added sugar consumption. Perhaps older mothers did not perceive that they needed to decrease their sugar consumption, despite receiving education and setting goals to reduce added sugar consumption. Gardner et al. found that pregnant women who perceived their current intake to be excessive were significantly more likely to intend to eat less high-sugar foods than those who believed their intake to be adequate (Gardner et al., 2012). Further research in similar populations is needed to better understand how age might influence effectiveness of interventions aimed at dietary change in this population.

As expected, participants’ perceived control to eat and drink low fat items at baseline moderated their ability to decrease fat intake, thereby supporting the TBP and social-cognitive theory that hypothesize that the level of perceived control to make a change is an essential prerequisite for behavior change (Ajzen, 1991; Bandura, 2004; Povey et al., 2000). Guillaumie et al., in a systematic review of 23 interventions, found that both the TPB and social cognitive theory are most predictive of fruit and vegetable intake (Guillaumie, Godin, & Vezina-Im, 2010). To our knowledge, this has not been previously shown specifically for reducing fat intake. The findings from this study may suggest that, in practice, it may be important for lifestyle interventions that aim to reduce consumption of fat to assess baseline perceived control or self-efficacy for that behavior.

A number of expected moderators were not significant, including parity, depressive symptoms, access to healthy food, and years in the U.S. Although a study of dietary behaviors among low income postpartum women in Texas found that depression was associated with poorer dietary index scores, we did not find that depressive symptoms significantly moderated participants’ ability to make dietary changes (George, Milani, Hanss-Nuss, & Freeland-Graves, 2005). A recent study of pregnant Canadian women found that having had more than one previous pregnancy was associated with higher diet quality, and proximity to fast food, convenience stores, and grocery stores was not associated with diet quality after controlling for other participant characteristics such as age, marital status, and physical activity (Nash, Gilliland, Evers, Wilk, & Campbell, 2013). We were possibly underpowered to detect similar differences based on parity. Kieffer et al. have shown that years of residence in the U.S. did not affect baseline dietary behaviors in this study population, and we did not find that this moderated change in dietary behavior (Kieffer, Welmerink, et al., 2013).

No significant mediators of these dietary outcomes were identified in this study. Thus, our analysis does not support the hypothesis that the Healthy MOMs intervention changed the studied dietary behaviors by changing beliefs, perceived control, or behavioral intention.

This study has several limitations. First, we were likely underpowered to detect differences between groups in many of the variables that we examined, particularly for the mediator analysis. Some mediators may be more important for particular subgroups of pregnant women, and larger numbers are needed to detect such differences. Future research on mediating mechanisms of lifestyle interventions within larger groups of pregnant Latina women could provide valuable information for tailoring interventions. Second, low variation and high baseline scores in several of the variables may have contributed to the limited ability to detect moderator and mediator effects, as there was little area for improvement in many variables. This may have contributed to our inability to demonstrate several of the hypothesized mediators. Third, dietary intake measures were based on participants’ self-reported responses. This type of dietary intake data collection, however, has been found to be useful for measuring periods over several months (Wei et al., 1999; Willet & Lenart, 1998). Fourth, measures of the hypothesized mediators, such as intention to eat healthy, were self-reported and subject to desirability bias, which may have led to over-reporting of “favorable” eating behaviors (Mossavar-Rahmani et al., 2013). Lastly, there are also likely other potential moderators and mediators of intervention effectiveness that may be important and were not measured in this study. For example, health literacy has been shown to moderate intervention effectiveness in diabetes self-management interventions and may have also moderated effectiveness in this study (Piette, Resnicow, Choi, & Heisler, 2013). This construct was not measured in this study. There are also potentially other psychological, cognitive, family and environmental factors that determine whether and how people may make dietary changes in response to an intervention that were not captured, or the measures may not be sufficiently sensitive. Further research is needed to understand unmeasured aspects of the intervention that contributed to its effectiveness.

This study has several strengths as well. This study seeks to understand how best to tailor interventions for an important and growing minority population in the US (Kieffer, Caldwell, et al., 2013; Kieffer et al., 2014; Kieffer, Welmerink, et al., 2013). It helps to elucidate baseline characteristics of those who might benefit, or not, in interventions seeking to improve dietary behaviors. Moreover, by better understanding mediators and moderators of a CHW intervention, we help to address current gaps in the literature on randomized controlled trials, particularly those targeting pregnant Latina women (Kraemer et al., 2002). The results of this study show that some factors, including age, spousal support, and baseline perceived control to make dietary changes may moderate intervention effectiveness for certain diet changes. In practice, these may be important characteristics to consider when designing and implementing lifestyle interventions for pregnant Latina women. Future interventions may benefit from using CBPR principles to develop tailored strategies that target specific dietary behaviors, and more specifically work to strengthen perceived behavioral control and spousal support, among pregnant Latina women.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

Financial Disclosure: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn JG. People need people. Perspectives on the meaning and measurement of social support. [Review] Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1991;26(4):325–329. doi: 10.1007/BF02691069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodick G, Elchalal U, Sella T, Heymann AD, Porath A, Kokia E, Shalev V. The risk of overt diabetes mellitus among women with gestational diabetes: a population-based study. Diabet Med. 2010;27(7):779–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, Ledikwe JH, Beach AM, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density in the treatment of obesity: a year-long trial comparing 2 weight-loss diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(6):1465–1477. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(3):171–178. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre H, Kahn R, Robertson RM, Committee, A. A. A. C. W. Preventing cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes: a common agenda for theAmerican Cancer Society, the American Diabetes Association, and the American Heart Association. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(4):190–207. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B, Croker H, Barr S, Briley A, Poston L, Wardle J, Trial U. Psychological predictors of dietary intentions in pregnancy. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2012;25(4):345–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George GC, Milani TJ, Hanss-Nuss H, Freeland-Graves JH. Compliance with dietary guidelines and relationship to psychosocial factors in low-income women in late postpartum. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(6):916–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review] Am J Health Promot. 1996;11(2):87–98. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumie L, Godin G, Vezina-Im LA. Psychosocial determinants of fruit and vegetable intake in adult population: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley K, Eskenazi B. Time in the United States, social support and health behaviors during pregnancy among women of Mexican descent. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(12):3048–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into practice: a review of community interventions. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(2):309–320. doi: 10.1177/0145721708330153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katula JA, Vitolins MZ, Morgan TM, Lawlor MS, Blackwell CS, Isom SP, Goff DC., Jr The Healthy Living Partnerships to Prevent Diabetes study: 2-year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4 Suppl 4):S324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey KS, Kirkley BG, De Vellis RF, Earp JA, Ammerman AS, Keyserling TC, Simpson RJ. Social support as a predictor of dietary change in a low-income population. Health Educaction Research. 1996;11(3):383–395. [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer EC. Maternal obesity and glucose intolerance during pregnancy among Mexican-Americans. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14(1):14–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer EC, Caldwell CH, Welmerink DB, Welch KB, Sinco BR, Guzman JR. Effect of the healthy MOMs lifestyle intervention on reducing depressive symptoms among pregnant Latinas. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51(1–2):76–89. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer EC, Salabarría-Peña Y, Odoms-Young A, Willis S, Palmisano G, Guzman JR. The application of focus group methodologies to community-based participatory research. In: Israel B, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossy-Bass; 2013. pp. 249–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer EC, Welmerink DB, Sinco BR, Welch KB, Rees Clayton EM, Schumann CY, Uhley VE. Dietary outcomes in a Spanish-language randomized controlled diabetes prevention trial with pregnant Latinas. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):526–533. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer EC, Welmerink DB, Sinco BR, Welch KB, Schumann CY, Uhley V. Periconception diet does not vary by duration of US residence for Mexican immigrant women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(5):652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristal AR, Feng Z, Coates RJ, Oberman A, George V. Associations of race/ethnicity, education, and dietary intervention with the validity and reliability of a food frequency questionnaire: the Women’s Health Trial Feasibility Study in Minority Populations. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(10):856–869. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford CP, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP. Social support: a conceptual analysis. [Review] J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(1):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe A, Weisnagel SJ, Provencher V, Begin C, Dufour-Bouchard AA, Trudeau C, Lemieux S. Using restrictive messages to limit high-fat foods or nonrestrictive messages to increase fruit and vegetable intake: what works better for postmenopausal women? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(2):194–202. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaño D, Danuta K, Taplin S. The theory of reason action and the theory of planned behavior. In: Glanz K, Lewis F, Rimer B, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1997. pp. 85–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Tinker LF, Huang Y, Neuhouser ML, McCann SE, Seguin RA, Prentice RL. Factors relating to eating style, social desirability, body image and eating meals at home increase the precision of calibration equations correcting self-report measures of diet using recovery biomarkers: findings from the Women’s Health Initiative. [Observational Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Nutr J. 2013;12:63. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash DM, Gilliland JA, Evers SE, Wilk P, Campbell MK. Determinants of diet quality in pregnancy: sociodemographic, pregnancy-specific, and food environment influences. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(6):627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.04.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostbye T, Krause KM, Lovelady CA, Morey MC, Bastian LA, Peterson BL, McBride CM. Active Mothers Postpartum: a randomized controlled weight-loss intervention trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(3):173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Resnicow K, Choi H, Heisler M. A diabetes peer support intervention that improved glycemic control: mediators and moderators of intervention effectiveness. Chronic Illn. 2013;9(4):258–267. doi: 10.1177/1742395313476522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povey R, Conner M, Sparks P, James R, Shepherd R. The theory of planned behaviour and healthy eating: Examining additive and moderating effects of social influence variables. Psychol Health. 2000;14(6):991–1006. doi: 10.1080/08870440008407363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosland AM, Kieffer E, Israel B, Cofield M, Palmisano G, Sinco B, Heisler M. When is social support important? The association of family support and professional support with specific diabetes self-management behaviors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):1992–1999. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Multivariable model-building: a pragmatic approach to regression anaylsis based on fractional polynomials for modelling continuous variables. Vol. 777. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Two techniques for investigating interactions between treatment and continuous covariates in clinical trials. Stata Journal. 2009;9(2):230. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero L, Castillo A, Quinn L, Hochwert M. Translation of the diabetes prevention program’s lifestyle intervention: role of community health workers. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(2):127–137. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] Prev Med. 1987;16(6):825–836. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton PL, Kieffer EC, Salabarria-Pena Y, Odoms-Young A, Willis SK, Kim H, Salinas MA. Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: the role of social support. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(1):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valen MS, Narayan S, Wedeking L. An innovative approach to diabetes education for a Hispanic population utilizing community health workers. J Cult Divers. 2012;19(1):10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pligt P, Willcox J, Hesketh KD, Ball K, Wilkinson S, Crawford D, Campbell K. Systematic review of lifestyle interventions to limit postpartum weight retention: implications for future opportunities to prevent maternal overweight and obesity following childbirth. Obes Rev. 2013;14(10):792–805. doi: 10.1111/obr.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei EK, Gardner J, Field AE, Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Suitor CW. Validity of a food frequency questionnaire in assessing nutrient intakes of low-income pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 1999;3(4):241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1022385607731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen LK, Shepherd MD, Parchman ML. Family support, diet, and exercise among older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30(6):980–993. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willet WC, Lenart E. Reproducibility and validity of food frequency questionnaires. In: WC W, editor. Nutritional Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 101–147. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.