Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this paper is to examine the psychometric properties and construct validity of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ) using a modified 3-point response scale for oral administration with older adults.

Methods

In-home interviews were conducted with 269 participants aged 60 and older who were completing an eligibility interview for a randomized control trial. The INQ was administered orally, as were measures of social support, death and suicide ideation and meaning in life.

Results

A confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated acceptable fit, with all of the items loading significantly onto the associated latent variable of thwarted belongingness or perceived burdensomeness. Construct validity of the measure was supported through an examination of discriminant validity using constructs hypothesized by the interpersonal theory of suicide to be related to the measured constructs, including social support and social integration for thwarted belongingness, social worth and death ideation for perceived burdensomeness, and meaning in life and suicide ideation for both.

Conclusion

The INQ yields reliable and valid scores of thwarted belongingness and burdensomeness when administered orally using a shortened response scale with older adults. These results help establish the measure as a valuable and practical tool for use in the field of late-life suicide prevention.

Keywords: Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire, older adults, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, suicide prevention

Introduction

Rates of suicide are higher for both men and women in later life across much of the globe, often peaking in old age (WHO 2014). Studies have shown that the baby boom generation (and potentially subsequent birth cohorts) has even higher suicide rates than earlier cohorts, suggesting that late-life suicide rates may increase even further in the future (Phillips, Robin, Nugent, & Idler, 2010). As this issue becomes more pressing, so too does the need for a greater understanding of the factors that lead to suicidal thoughts and behaviors in later life.

The interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) has gained attention in recent years as a promising framework through which to examine and understand the psychological underpinnings of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The theory posits that the desire to die by suicide arises from two distinct but related constructs: thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Thwarted belongingness is conceptualized by this theory as a psychologically painful state arising from an unmet need for positive social connectedness, the “need to belong” (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Perceived burdensomeness occurs when an individual believes that he or she is a liability for others in his/her life and may involve beliefs that “others would be better off if I were gone.” According to the theory, individuals who experience both of these states are more likely to develop thoughts of suicide, a relationship that has been supported empirically in numerous studies (Davidson, Wingate, Rasmussen, & Slish, 2009; Nademin et al., 2008; Van Orden et al., 2008; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012; Van Orden, Lynam, Hollar, & Joiner, 2006; Van Orden, Witte, Gordon, Bender, & Joiner, 2008). The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ) was developed to measure the constructs of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012). Previous research has found that scores derived from the INQ demonstrate good psychometric properties and construct validity, including a demonstrated prospective association with suicide ideation (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012; Van Orden, Witte, Gordon, Bender, & Joiner, 2008). The construct validity of scores derived from the INQ has been demonstrated with older adults in two studies (Marty, Segal, Coolidge, & Klebe, 2012; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012). Van Orden and colleagues (2012) found that the underlying latent structure of the INQ applied to both a younger adult sample and an older adult primary care sample. Further, they found convergent associations for the older adult sample between thwarted belongingness and both loneliness and social support, and convergent associations for perceived burdensomeness with both lower social worth and death ideation. Marty and colleagues (2012) also found support for the construct validity of the scale with older adults, including concurrent associations between both subscales and hopelessness, low meaning in life, and suicide ideation. These qualities establish the INQ’s potential as a valuable and useful tool in the domain of suicide research and prevention and indicate its relevance to late-life suicide.

The INQ uses a seven-point Likert scale to measure subjects’ responses, ranging from “Not at all true for me” to “Very true for me” with a central response option of “Somewhat true for me” (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012). A seven-point scale was chosen due to findings that the reliability, validity, and discriminating power of scales generally increase with the number of response options up to seven, after which the differences are negligible (Lozano, García-Cueto, & Muñiz, 2008; Preston, & Colman, 2000). However, administration difficulties were encountered by the authors when the measure, with a 7-point scale, was orally administered to older participants. The measure was administered orally for several reasons. Oral administration may help compensate for sensory, functional, and cognitive impairments which are commonly comorbid with social isolation and elevated suicide risk in later life (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009; Perissinotto, Cenzer, & Covinsky, 2012), characteristics of the population for which the INQ was designed. It was also administered orally in order to maximize measure completion and thus improve the quality of the data, a practice that has empirical support (Hedman, et al., 2013; Moum, 1998), particularly with older adults, who are more likely to struggle with self-administered measure completion (Rutherford, Nixon, Brown, Lamping, & Cano, 2014). Prior research has found that socially desirable responding may have greater impact at younger than older ages: Moum (1998) found that older, but not younger, adults were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety and depression during in-person interviews than in self-administered measures; the opposite pattern was found for younger adults, for whom socially desirable responding may have been occurring. Given the practical benefits of oral administration, and evidence suggesting this mode of administration would not negatively impact the validity of scores on the INQ for older adults, the authors proceeded with using oral administration of the INQ with this population. However, when the INQ was administered orally in previous studies conducted by the authors, utilizing the seven-point response scale, participants often chose only three of the seven options with anchor points: one (“Not at all true for me”), four (“Somewhat true for me”), and seven (“Very true for me”). Adding anchor points to each option was considered, but given the time it would take to administer the scale orally with seven anchored options, the authors opted instead to reduce the number of response options in order to reduce subject burden and facilitate ease of administration.

Consistent with several well-established measures designed for use with older adults, including the Geriatric Anxiety Scale (GAS), the Older Adult Social-Evaluative Situations Questionnaire (OASES), and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), we shortened the response set in an effort to simplify the measure for use with the geriatric population (Gould, Gerolimatos, Ciliberti, Edelstein, & Smith, 2012; Yesavage et al., 1983; Yochim, Mueller, June, & Segal, 2011). A 3-point scale was used rather than a “yes/no” format because the authors hypothesized that including a third, central response of “somewhat true for me” would allow for a more sensitive measure of subjects’ experiences and provide a further degree of information regarding the intensity of their feelings than a 2-point scale, yet was unlikely to burden subjects with a confusing array of choices. A central response choice may also provide a seemingly safe option for subjects who feel defensive over the personal nature of the questions and who do not wish to identify strongly with a negative quality or experience. Though research examining the reliability, validity, and discriminating power of response scales has shown no significant difference between 2- and 3- point scales, the scales utilized in this prior research did not assess sensitive information, as the INQ does (Preston, & Colman, 2000); thus, the authors elected to use a 3-point response scale for the aforementioned reasons. Using a 3-point response scale for the administration of the INQ with older adults may therefore represent a sensitive, simplified, and practical measure for assessing belongingness and burdensomeness among this population.

Though no empirical research examining the benefits of utilizing shorter response sets with older adults has been published to our knowledge, many researchers propose that fewer response options aid in easing the administration of measures with the geriatric population (Yesavage et al., 1983; Yochim, Mueller, June, & Segal, 2011). In addition, research has shown that difficulties in completing measures via self-administration increase with age, impaired cognition, and poor health (McHorney, 1994). Thus, a shortened response scale may be useful in working with older adults, as fewer response options may reduce subject burden of this measure when administered orally and facilitate its use with this population.

Reducing the number of options on the response scale, however, may reduce the amount of variance observed across participants and thereby compromise reliability and validity of the scale (Lozano, García-Cueto, & Muñiz, 2008; Preston, & Colman, 2000), thus establishing a need to ensure that the questionnaire retains its psychometric properties and construct validity in its modified form. The aim of the current study is to empirically examine the psychometric properties and construct validity of the INQ for oral administration with the shortened response set. We believe that the results of this study will generalize to other geriatric measures for which oral administration may be useful. Very few studies have empirically examined the psychometric properties of scales when response options are reduced, despite this being a relatively common practice in geriatric measure development.

We first hypothesize that the items written to measure thwarted belongingness will load onto the “belongingness” factor and that the items written to measure burdensomeness will load onto the “burdensomeness” factor, thus supporting the validity of the measure’s latent structure. Secondly, it is also hypothesized that the analysis will demonstrate that the two constructs of thwarted belongingness and burdensomeness are related but distinct, as posited by the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010). In order to examine the construct validity of the modified INQ, discriminant validity will also be examined. In line with previous findings and the definitions of the constructs of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, our third hypothesis is that perceived burdensomeness will be significantly associated with lower meaning in life (Van Orden, Bamonti, King, & Duberstein, 2012), lower social worth, stronger death ideation (McPherson, Wilson, & Murray, 2007), and stronger suicide ideation (Van Orden et al., 2010). Our fourth hypothesis is that thwarted belongingness will be significantly associated with lower social network integration, lower social support (Van Orden et al., 2010), as well as lower meaning in life (Van Orden, Bamonti, King, & Duberstein, 2012) and stronger suicide ideation (Van Orden et al., 2010).

Methods

Participants

Participants were 269 community-dwelling adults aged 60 and older (M = 71.07; SD = 8.39) who were recruited from University of Rochester-affiliated primary care offices. The participants were screened for inclusion in The Senior Connection (NCT01408654), a randomized controlled trial of peer companionship. The sample included 193 women (72%) and 76 men (28%); 82% of the sample was White (1% Hispanic), 13% was African American, and 5% identified as multiracial or other.

Procedures

Primary care patients who endorsed recent feelings of loneliness (i.e., “I feel lonely”) and/or burdensomeness (i.e., “I feel like a burden on others”) during a brief screen were eligible to participate. In order to make the study more accessible for older adults, the interviews were conducted in participants’ homes. Data for the current paper used measures from the baseline eligibility interview only and all measures were administered prior to randomization. All measures were administered orally in an effort to prevent strain due to sensory impairment. All participants were assessed for suicide risk and a protocol was followed to ensure appropriate follow-up in the event of current suicidal ideation. This study was approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012)

The self-report measure includes 15 items, 9 of which measure thwarted belongingness and 6 of which measure perceived burdensomeness. A modified 3-point rating scale was used in this study, with higher scores indicating greater thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.

Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale (Heisel & Flett, 2006)

The GSIS was designed to measure death and suicide ideation as well as proximal risk factors for suicide ideation in older adults. The measure includes four subscales, which are scored separately. Higher scores on the suicide ideation subscale indicate more frequent and stronger thoughts of suicide. Higher scores on the death ideation subscale indicate more frequent and stronger wishes for one’s death. The meaning in life subscale is an assessment of a posited protective factor, with higher scores indicting greater meaning in life. The perceived social worth subscale is an indicator of perceived social acceptability and value of the self, with higher scores signifying lower perceived social worth.

Berkman Social Network Index (Berkman & Syme, 1979)

The measure was designed to assess social network size and strength through items regarding social contacts and participation. The questions inquire about friends and family, measured using numeric scales, as well as involvement in community groups, which is assessed with scales ranging from no involvement to very frequent involvement. The measure was scored as a continuous variable, with higher summed scores indicating greater social integration.

Duke Social Support Index (Landerman et al., 1989)

The scale was designed to measure various aspects of functional social support. In this study we used a subscale of the measure to assess perceived instrumental social support in hypothetical situations of need. Items include questions about help with potential needs regarding daily activities and care, financial assistance, and emotional support. Items are scored using a yes/no scale, with higher scores indicating greater instrumental social support.

Data Analysis

To test hypotheses one and two, we fit a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model using Mplus Version 7.11. We used the robust weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) because the CFA indicators (i.e., INQ items) were categorical. We specified the model described in Van Orden et al. (2012), with six items loading onto the perceived burdensomeness latent variable and nine items loading on the thwarted belongingness latent variable. We examined model fit using guidelines described by Brown (2006). To test hypotheses three and four, regarding discriminant validity, we constructed a structural equation model using the measurement model developed for hypothesis one and six observed dependent variables.

Results

See Table 1 for the proportion of subjects endorsing each INQ item. As predicted by the theory, fewer subjects endorsed the perceived burdensomeness items compared to the thwarted belongingness items.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for INQ items

| Proportion, N | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Description | Not at all true | Somewhat true | Very true | |||

| Bur1 | Better off | 0.911 | 245 | 0.082 | 22 | 0.007 | 2 |

| Bur2 | Happier | 0.907 | 243 | 0.090 | 24 | 0.004 | 1 |

| Bur3 | Society | 0.866 | 233 | 0.123 | 33 | 0.011 | 3 |

| Bur4 | Relief | 0.937 | 252 | 0.059 | 16 | 0.004 | 1 |

| Bur5 | Rid of me | 0.929 | 250 | 0.063 | 17 | 0.007 | 2 |

| Bur6 | Worse | 0.869 | 233 | 0.123 | 33 | 0.007 | 2 |

| Bel1 | Care | 0.717 | 193 | 0.264 | 71 | 0.019 | 5 |

| Bel2 | Belong | 0.515 | 138 | 0.414 | 111 | 0.071 | 19 |

| Bel3 | Interact | 0.717 | 193 | 0.219 | 59 | 0.063 | 17 |

| Bel4 | Friends | 0.554 | 149 | 0.301 | 81 | 0.145 | 39 |

| Bel5 | Disconnected | 0.507 | 136 | 0.403 | 108 | 0.09 | 24 |

| Bel6 | Outsider | 0.442 | 119 | 0.379 | 102 | 0.178 | 48 |

| Bel7 | Turn to | 0.639 | 172 | 0.297 | 80 | 0.063 | 17 |

| Bel8 | Close | 0.398 | 107 | 0.498 | 134 | 0.104 | 28 |

| Bel9 | Interaction | 0.405 | 109 | 0.424 | 114 | 0.171 | 46 |

To examine the viability of the CFA model using the 3-pt scale, we examined model fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; 0.068) indicates adequate fit (i.e. close to <.06). Values for both the comparative fit index (CFI; 0.966) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; 0.960) exceed cut-off values for acceptable fit (i.e., .95). While the chi-square test of model fit is inconsistent with adequate fit (3313.407, p<.05), this index is sensitive to sample size and may underestimate the degree of model fit (Brown, 2006).

Parameter estimates for the model – the estimated (unstandardized and standardized) factor loadings, R-square values (i.e. communalities), and latent variable covariances – are displayed in Table 2. All items significantly loaded onto the specified latent variable and r-square values range from 0.359 to 0.925, with most values falling somewhere in between, indicating moderate magnitudes (i.e., in the .50 – .70 range).

Table 2.

Model Estimated Understandardized and Standardized Factor Loadings, Covariances, R-square

| Est | Std Err | P value | Stand | R-sq | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BURDEN | 0.925 | 0.046 | <.001 | – | |||

| Bur1 | Better off | INQ1 | 1 | 0 | – | 0.962 | 0.925 |

| Bur2 | Happier | INQ2 | 1.005 | 0.034 | <.001 | 0.966 | 0.934 |

| Bur3 | Society | INQ3 | 0.859 | 0.056 | <.001 | 0.826 | 0.683 |

| Bur4 | Relief | INQ4 | 1 | 0.041 | <.001 | 0.962 | 0.925 |

| Bur5 | Rid of me | INQ5 | 0.895 | 0.057 | <.001 | 0.861 | 0.742 |

| Bur6 | Worse | INQ6 | 0.784 | 0.063 | <.001 | 0.754 | 0.569 |

| BELONG | 0.667 | 0.058 | <.001 | – | |||

| Bel1 | Care | INQ8 | 1 | 0 | – | 0.817 | 0.667 |

| Bel2 | Belong | INQ9 | 1.034 | 0.054 | <.001 | 0.844 | 0.712 |

| Bel3 | Interact | INQ10 | 0.734 | 0.072 | <.001 | 0.599 | 0.359 |

| Bel4 | Friends | INQ11 | 0.896 | 0.056 | <.001 | 0.731 | 0.535 |

| Bel5 | Disconnected | INQ12 | 0.942 | 0.054 | <.001 | 0.769 | 0.592 |

| Bel6 | Outsider | INQ13 | 0.752 | 0.066 | <.001 | 0.614 | 0.377 |

| Bel7 | Turn to | INQ14 | 1.043 | 0.059 | <.001 | 0.851 | 0.725 |

| Bel8 | Close | INQ15 | 1.013 | 0.053 | <.001 | 0.827 | 0.684 |

| Bel9 | Interaction | INQ16 | 0.745 | 0.062 | <.001 | 0.609 | 0.370 |

| Covariance | 0.457 | 0.068 | <.001 | 0.604 |

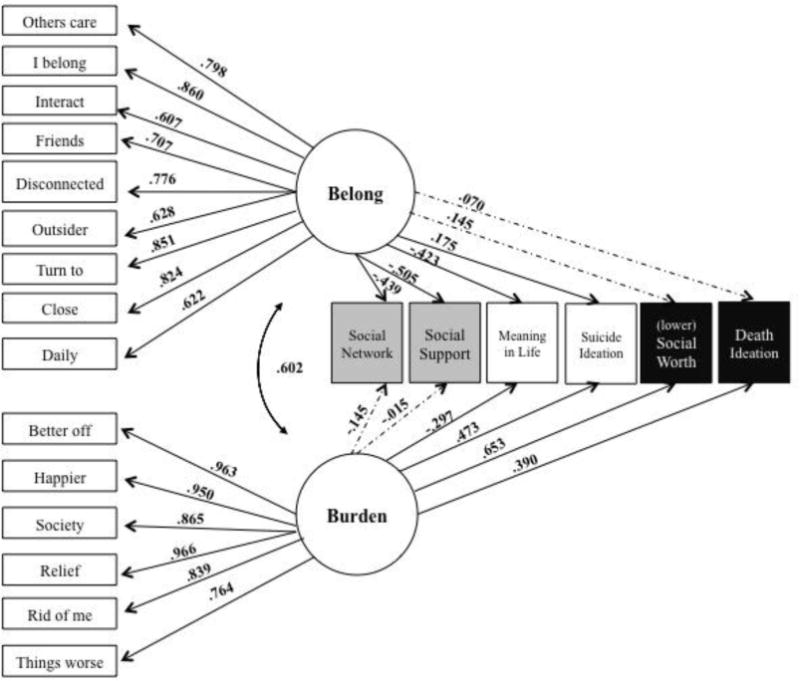

To examine the construct validity of scores derived from the INQ, we examined discriminant validity with constructs hypothesized by the theory to be associated (or not) with thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, or both. Model fit indices for the structural equation model were acceptable: the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; 0.058) indicates good fit (i.e. <.06). Values for both the comparative fit index (CFI; 0.954) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; 0.943) approach cut-off values for acceptable fit (i.e., .95), while the chi-square test of model fit is inconsistent with adequate fit (320.586, p<.05). Regarding parameter estimates (see Figure 1), thwarted belongingness was significantly associated with lower social network integration (on the Berkman Social Network Index) and lower instrumental social support (on the Duke Social Support Index); burdensomeness was not significantly associated with these constructs, as anticipated. In line with our hypotheses, both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness were significantly associated with greater severity of suicide ideation and lower meaning in life (both on the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale). Finally, also consistent with our hypotheses, perceived burdensomeness was significantly associated with greater severity of death ideation and lower personal and social worth (both on the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale); thwarted belongingness was not significantly associated with these constructs.

Figure 1.

Convergent and Divergent Validity for the INQ subscales of Thwarted Belongingness and Perceived Burdensomeness

Note. Standardized loadings appear on the lines. Dotted line indicates a statistically non-significant loading (i.e., p ≥ .05). Grey boxes represent constructs hypothesized to be associated with belongingness; white boxes hypothesized to be associated with both belongingness and burdensomeness; and black boxes hypothesized to be associated with burdensomeness.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire yields reliable and valid scores of the constructs of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness when orally administered using a shortened response scale with older adults. In support of our first hypothesis, analyses indicate that the nine thwarted belongingness items on the INQ loaded significantly on a thwarted belongingness latent variable, and the six perceived burdensomeness items loaded significantly onto a perceived burdensomeness latent variable. In support of our second hypothesis that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would represent related but distinct constructs, a model with two latent variables produced acceptable model fit and the covariance between the two was moderate. In support of our final hypotheses, analyses indicate that the scale demonstrates good construct validity, as evidenced by discriminant validity with related constructs, including a positive association with suicide ideation. These findings demonstrate that orally administering the modified version of the INQ with a shortened 3-point response scale does not compromise the validity of the measure.

Reducing the response set of the INQ from a seven-point scale to a three point-scale has numerous benefits, particularly in regards to its use with the geriatric population. Other scales designed for use with older adults have shortened response scales, including the GDS, which uses a yes/no format, and the GAS and OASES, which use a four-point scale (Gould, Gerolimatos, Ciliberti, Edelstein, & Smith, 2012; Yesavage et al., 1983; Yochim, Mueller, June, & Segal, 2011). The shortened length of the response scale is thought to make the response options more easily understood and recalled by subjects, which is particularly helpful among populations such as older adults that are at risk for cognitive impairment. Also, in situations where the measure is administered orally for the benefit of subjects or patients who may be dealing with sensory impairments—again a common issue and subsequent practice with older adults—shortening the response scale may make administration simpler, more comprehensible and more time-efficient for the patients as well as for researchers and clinicians.

One limitation of these analyses is that, due to the use of cross-sectional data, the predictive validity of the INQ regarding suicide ideation could not be assessed. While the analyses demonstrate a strong concurrent relationship between the constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness and suicide ideation as predicted by the interpersonal theory of suicide, a causation relationship could not be determined. Without the ability to establish causality, a significant function of the scale is left unsubstantiated. Another limitation is that we did not examine whether the scale performs differentially well among men and women, and across the age range of older adulthood, given the size of our sample. This is an important direction for future research with the INQ, as suicide rates vary significantly based on gender, and the challenges of older adulthood change significantly from young old to the oldest old ages. Another limitation of this study is that, as all measures were orally administered unlike in previous studies, we do not know the effect that the shortened response scale will have on its psychometric profile if the scale is self-administered. Ideally, our study would have allowed us to compare scores on the INQ with the shortened response scale for an orally administered group of subjects and a self-administered group of subjects; given that our sample was collected as part of an inclusion screen for a randomized trial, these procedures were not feasible. Despite support from prior research demonstrating that oral administration of the measure may not be as influenced by social desirability responding as might be presumed (Brewer, Hallman, Fiedler, & Kipen, 2004; Moum, 1998), especially among older adults, oral administration of the scale may still be a limitation, as the INQ items may be more sensitive than symptoms of depression and anxiety (about which previous research was conducted); for example, older adults who perceive themselves to be a burden on others may experience shame as a result of this perception and thus may be reluctant to admit this to an interviewer. Future studies of the INQ with older adults could randomize participants to either the self-report or orally-administered versions and compare completion rates, as well as predictive validity of scores derived from the measure. Further research should also be conducted examining the procedural benefits of utilizing shorter response scales with older adults and potential psychometric costs. As we did not empirically examine 2- versus 3-point response scales, further research could also be conducted to examine the potential psychometric costs of the scale using a 2-point yes/no format, given that a yes/no format may confer additional practical benefits. Another potential direction for future research is to examine the possibility of using the modified INQ in studies of other populations that may similarly benefit from a shorter response scale, such as children.

In previous research with young adults, middle-aged adults, and older adults, the psychometric properties of Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire were established. The shortened response format of the INQ with oral administration has now similarly demonstrated its positive psychometric properties and construct validity with older adults, of particular importance given the need for theory-based research in the domain of late-life suicide prevention. We believe these results have implications for the field of clinical geropsychology. Specifically, our results suggest that the procedural benefits of reducing response options for oral administration (i.e., ease of administration, reduction of missing data) are not outweighed by the reduced amount of variance that can be observed across participants: we found that the INQ retained its strong psychometric properties and construct validity when administered orally with a shortened 3-point response set. As the older adult population increases in the coming years, more psychological measures will likely need to be adapted for older adults. Thus, a literature examining the process of adaptation for administration with older adults is needed. Our results suggest that a modification of reducing the response set of items from 7 points to 3 points for oral administration may be a viable option for other psychological measures to be used with older adults.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Grant Nos. U01CE001942 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and K23MH096936 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Kimberly A. Parkhurst, University of Rochester School of Medicine

Yeates Conwell, University of Rochester School of Medicine.

Kimberly A. Van Orden, University of Rochester School of Medicine

References

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine year follow-up study of Alameda county residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109(2):186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer NT, Hallman WK, Fiedler N, Kipen HM. Why do people report better health by phone than by mail? Medical Care. 2004;42(9):875–883. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135817.31355.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13(10):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson CL, Wingate LR, Rasmussen KA, Slish ML. Hope as a predictor of interpersonal suicide risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2009;39(5):499–507. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould CE, Gerolimatos LA, Ciliberti CM, Edelstein BA, Smith MD. Initial evaluation of the older adult social-evaluative situations questionnaire: A measure of social anxiety in older adults. International Psychogeriatrics. 2012;24(12):2009–2018. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Blom K, Alaoui SE, Kraepelien M, Ruck C, Kaldo V. Telephone versus internet administration of self-report measures of social anxiety, depressive symptoms, and insomnia: Psychometric evaluation of a method to reduce the impact of missing data. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(10):131–138. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisel MJ, Flett GL. The development and initial validation of the geriatric suicide ideation scale. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(9):742–751. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000218699.27899.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. United States of America: First Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Landerman R, George LK, Campbell RT, Blazer DG. Alternative models of the stress buffering hypothesis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17(5):625–642. doi: 10.1007/BF00922639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano LM, García-Cueto E, Muñiz J. Effect of the number of response categories on the reliability and validity of rating scales. Methodology. 2008;4(2):73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Marty MA, Segal DL, Coolidge FL, Klebe KJ. Analysis of the psychometric properties of the interpersonal needs questionnaire (INQ) among community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68(9):1008–1018. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA. Measuring and monitoring general health status in elderly persons: Practical and methodological issues in using the SF-36 Health Survey. Gerontologist. 1994;36:551–567. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson CJ, Wilson KG, Murray MA. Feeling like a burden to others: A systematic review focusing on the end of life. Palliative Medicine. 2007;21(2):115–128. doi: 10.1177/0269216307076345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moum T. Mode of administration and interviewer effects in self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression. Social Indicators Research. 1998;45(1–3):279–318. [Google Scholar]

- Nademin E, Jobes DA, Pflanz SE, Jacoby AM, Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Campise R, Johnson L. An investigation of interpersonal-psychological variables in Air Force suicides: A controlled-comparison study. Archives of Suicide Research. 2008;12(4):309–326. doi: 10.1080/13811110802324847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(14):1078–1084. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA, Robin AV, Nugent CN, Idler EL. Understanding recent changes in suicide rates among the middle-aged: Period or cohort effects? Public Health Reports. 2010;125(5):680–688. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston CC, Colman AM. Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychologica. 2000;104(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(99)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford C, Nixon J, Brown JM, Lamping DL, Cano SJ. Using mixed methods to select optimal mode of administration for a patient-reported outcome instrument for people with pressure ulcers. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(22) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Bamonti PM, King DA, Duberstein PR. Does perceived burdensomeness erode meaning in life among older adults? Aging & Mental Health. 2012;16(7):855–860. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.657156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TEJ. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the interpersonal needs questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(1):197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Lynam ME, Hollar D, Joiner TEJ. Perceived burdensomeness as an indicator of suicidal symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30(4):457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TEJ. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TEJ. Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(1):72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, James LM, Castro Y, Gordon KH, Braithwaite SR, Joiner TEJ. Suicidal ideation in college students varies across semesters: The mediating role of belongingness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:427–435. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. Luxembourg: 2014. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/131056/1/9789241564779_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1983;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochim BP, Mueller AE, June A, Segal DL. Psychometric properties of the geriatric anxiety scale: Comparison to the beck anxiety inventory and geriatric anxiety inventory. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health. 2011;34(1):21–33. [Google Scholar]