Abstract

Psychosocial problems increase the risk for mental health problems and increase the need for health care services in children and adolescents. Primary care practice is a valuable avenue for identifying the need for more specialized mental health care. We hypothesized that Korean version of the pediatric symptom checklist (PSC) would be a useful tool for early detection of psychosocial problems in children and adolescents in Korea and we aimed to suggest cut-off scores for detecting meaningful psychosocial problems. A total of 397 children with their parents and 97 child patients with their parents were asked to complete the PSC Korean version and the child behavior checklist (CBCL). The internal reliability and test-retest reliability of the PSC as well as the cut-off score of the PSC was determined via receiver operating characteristic analysis of the CBCL score, clinical group scores and non-clinical group scores. The internal consistency of the PSC-Korean version was excellent (Cronbach's alpha = 0.95). The test-retest reliability was r = 0.73 (P < 0.001). Using clinical CBCL scores (total score, externalizing score, internalizing score, respectively ≥ 60) and presence of clinical diagnosis, the recommended cut-off score of the PSC was 14. Using 494 Korean children aged 7-12 yr, the current study assessed the reliability and validity of a Korean version of the PSC and suggested a cut-off for recommending further clinical assessment. The present results suggest that the Korean version of the PSC has good internal consistency and validity using the standard of CBCL scores.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Psychosocial Problems, Pediatric Symptom Checklist, Child Behavior Checklist, Cut-off

INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies and reports have suggested that psychosocial problems increase the risk for mental health problems and increase the need for health care services in children and adolescents (1,2). Primary care practice is a valuable avenue for treating and/or identifying the need for more specialized behavioral health care including health behavior change, mental health care, management of psychological symptoms and psychosocial distress, and control of substance abuse (2). Frequently, psychosocial problems in children are not treated with early intervention (3). Unfortunately, untreated psychosocial problems in childhood are thought to lead to dysfunctions in adulthood, including conditions that require expensive interventions (4). In the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study of 17,000 adult patients with medical problems, Van Niel et al. (5) reported that patients with more adverse experience during childhood experienced higher rates of smoking, alcohol abuse, obesity, and physical inactivity. Therefore, early detection and intervention of psychosocial problems in children are important for prevention and amelioration of lifelong ailments and maintenance of community health.

Traditionally, the primary medical service provided by pediatricians has been thought to be an opportunity for recognition of psychosocial problems in children (6). Pediatricians reported that improving training for evaluating and managing behavioral problems in children is necessary to meet the demands of much needed behavioral health care for children and parents (6). However, pediatricians often hesitate to identify psychiatric problems due to lack of psychiatric training (7). In addition, limited time for analysis makes it difficult for primary physicians to detect psychosocial problems in children, especially early in life (8). In fact, the literature has revealed that less than 50% of children are screened by primary care physicians for psychosocial problems, and very few children meet with psychiatrists (7).

For early and effective recognition of psychosocial problems in children, Jellinek et al. (9) designed a screening tool called the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) in 1986 and then developed it further (9,10,11,12). Initially, the PSC was targeted for children 6 to 12 yr old, but was subsequently extended to cover children from 4 to 18 yr of age (9,13). The PSC has been used successfully in the United States of America (USA) due to its easy application for screening of psychosocial problems. In addition, other countries have adopted the PSC into their own language and culture for screening of psychosocial problems. For example, a Spanish group in the USA studied the reliability and validity of the PSC for children aged 4 to 5 yr (11). Also, children from 7 to 12 yr of age in the Netherlands and 5-yr old children in Austria also were studied for early detection of psychosocial problems using the PSC (14,15). However, there is currently few effective tool for screening or early detection of psychosocial problems in Korean children.

Based on the studies conducted in other countries, we hypothesized that a Korean version of the PSC would be a useful tool for early detection of psychosocial problems in children and adolescents in Korea. In the PSC optimized for Korean children, we aimed to suggest cut-off scores for detecting meaningful psychosocial problems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The information for analysis of the PSC was gathered from a clinical sample and a non-clinical sample.

Non-clinical sample

A total of 420 children, ranging in age from 6 to 12 yr, who lived in Daegu, a city in southeastern Korea with approximately 2.5 million habitants, were recruited from local schools. Permission was obtained in advance from the headmaster and teacher and parents' committee of the school board of the school in which the study was performed.

Written protocol and instructions had been distributed to the parents by the delivery of the students in each classroom. Participants were not compensated.

The PSC and the child behavior checklist (CBCL) were distributed to the 420 participants and their parents. A total of 403 students and their parents read the protocol and instructions and returned the PSC and the CBCL (response rate 95.9%). Seventeen participants were excluded due to lack of agreement to participate because of absence having chronic physical illness (n=8), psychiatric problems (n=3) or physical problems (n=6) of students according to teachers' information. After excluding six participants due to even single missing data point in the PSC and the CBCL, the information from 397 children and their parents were used in the analysis.

Clinical sample

One hundred patients who visited the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kyungpook National University Hospital were recruited. Inclusion criteria were 1) age 6-12 yr, 2) diagnosed with a psychiatric disease, 3) no chronic medical illnesses, and 4) living with main caretakers. Among the 100 responses, data from three patients were excluded due to incomplete responses even with a single missing data point. Parents answered the PSC during the waiting time at their first visit. Psychiatric diagnosis of the clinical group made by the child and adolescent psychiatrists had been described in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic data of the non-clinical and clinical groups.

| Variables | Non-clinical group | Clinical group | t/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of children | 397 | 97 | ||

| Age (M ± SD) | 9.25 ± 1.48 | 8.90 ± 1.77 | t = 1.58 | 0.10 |

| Sex | ||||

| Boys, No. (%) | 191 (48.1) | 73 (75.2) | ||

| Age (M ± SD) | 9.20 ± 1.52 | 8.91 ± 1.69 | t = 1.34 | 0.80 |

| Girls, No. (%) | 206 (51.9) | 24 (24.8) | ||

| Age (M ± SD) | 9.30 ± 1.44 | 9.16 ± 2.01 | t = 0.41 | < 0.01 |

| Parental education, yr (M ± SD) | ||||

| Father | 15.64 ± 0.50 | 14.61 ± 0.25 | t = 5.98 | < 0.001 |

| Mother | 15.42 ± 1.50 | 14.06 ± 2.33 | t = 6.71 | < 0.001 |

| Caretakers sharing a home, No. (%) | χ2 = 0.86 | 0.64 | ||

| Both parents | 355 (89.4) | 91 (93.8) | ||

| One parent | 25 (6.2) | 4 (4.1) | ||

| Other | 6 (1.5) | 2 (2.0) | ||

| Socioeconomic status* | χ2 = 83.50 | <0.001 | ||

| Upper & upper-middle | 39 (9.8) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Middle | 333 (83.8) | 66 (68.0) | ||

| Lower-middle & lower | 15 (3.7) | 18 (18.5) | ||

| Psychiatric diagnosis, No. (%) | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) 47 (48.5) | |||

| Major Depressive Disorder 17 (17.5) | ||||

| ADHD+Oppositional Defiant Disorder 12 (12.4) | ||||

| Tourette's Disorder 10 (10.3) | ||||

| Selective Mutism 4 (4.1) | ||||

| Separation Anxiety Disorder 4 (4.1) | ||||

| Enuresis 2 (2.1) | ||||

| Mental Retardation 1 (1.0) | ||||

*Socioeconomic status was classified according to methods of Hollingshead and Redlich. M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Measure and scales

Pediatric symptom checklist

The PSC consisted of 35 questions regarding the parents' impressions of psychosocial problems in their children (10,13). The answer choices consisted of 'never,' 'sometimes' and 'frequently,' which were allocated 0, 1 or 2 points, respectively. Higher PSC scores represented more psychosocial problems in the children and adolescents.

The PSC-Korean version was developed with a forward-backward translation procedure. It was translated by a bilingual person, and a consensus procedure was performed with a Korean child and adolescent psychiatrist. Another bilingual translator performed a blinded backward-translation to English, and the final version of the PSC was obtained after some adjustments. When translating and adapting this instrument, the Korean culture and language were taken into account. Compared to the original version of the PSC, several words and phrases were modified to maintain the meaning. For example, item number 8, 'Daydreams too much' had been translated into 'Dazed often' in Korean because not all Korean people are familiar with the meaning of the word 'daydream'. Item number 29, 'Does not listen to rules' had been translated into 'Disobeys rules' and Item number 34, 'Take things that do not belong to him or her' into 'Steal things' because they were clearer than the directly translated in meaning in Korean. In order to evaluate the test-retest reliability of the Korean PSC, 180 students were randomly selected to complete the PSC scale again four weeks later. Among these 180 participants, 140 returned the second PSC.

Child behavior checklist (CBCL)

The CBCL, developed by Achenbach, is a tool for the assessment of children and adolescents (16). It consists of two parts: a social competence scale and a syndrome and total problem scale. A CBCL-Korean version has already been developed and is currently used by clinicians (17). The CBCL-Korean version consists of a 132-item questionnaire, and responses are provided on a three-point Likert scale from 0 to 2. The social competence scale assesses social interaction, school performance and overall social competence. In school performance scale, average scores of total 5 subjects has been calculated such as Korean, mathematics, social science, science, and English, only in case of middle school students. The syndrome and total problem scale includes social withdrawal, somatic complains, anxiety, depression, attention problems, aggressive behavior, externalized dysfunction, internalized dysfunction and dissocial behavior. Higher CBCL scores represent more severe psychosocial problems. The score is recorded as a raw score and is translated into a T score. Although a 63 or more T score (90 percentile) has been generally considered clinical, the clinical referred cut-off score is a 60 or more T score (85 percentile) in non-clinical samples and a 70 or more T score (98 percentile) in clinical samples. In this study, we used a 60 or more T score, because we developed the PSC to screen psychosocial problems in a general population of children and adolescents.

Statistical analysis

Demographic variables between the non-clinical and clinical groups were analyzed with a t-test and a chi-square-test. The internal reliability and test-retest reliability of the PSC were assessed with Cronbach's alpha and Pearson's correlation coefficient (r). The inter-correlation fit among the four factors in the PSC was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with structural equation modeling (18). For the validity of the PSC-Korean version, transformed CBCL scores (total, internalizing and externalizing scores) were correlated with total score of the PSC-Korean version (Pearson's correlation coefficient, r) as was performed in the development of the PSC-Dutch version (14). One-way ANCOVA was used to demonstrate discriminant validity of the Korean version of the PSC between the non-clinical group and clinical group with the covariates of sex, parental educational status, and economic status. The cut-off score was determined via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of the CBCL score (total problem score, internalizing score and externalizing score), clinical group scores and non-clinical group scores. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0 for Windows and LISREL 8.80.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by institutional review board of the Kyungpook National University Hospital (IRB No., 20110 5012). Written informed consent was provided by all study participants. Permission was obtained from all of the participants including parents and students.

RESULTS

Demographic data

The mean age of all the subjects was 9.3±1.5 yr. The mean age and years of education for the parents who filled out the PSC were 37.3±2.9 and 15.3±1.8, respectively (Table 1). There were no significant differences in age, parent age or parenting status between the non-clinical and clinical groups. The mean age of the non-clinical and clinical groups was 9.25±1.48 yr and 8.90±1.77 yr, respectively. However, there were significant differences in years of parents' education (father: t=5.98, P<0.001, mother: t=6.71, P<0.001) and social economic status (χ2=83.5, P<0.001) between the groups. The mean years of education in the clinical and non-clinical groups were 14.34±1.29 yr and 15.53±1.00 yr, respectively. The clinical group comprised more participants in the lower-middle social economic status compared to the non-clinical group (χ2=83.50, P<0.001) (Table 1).

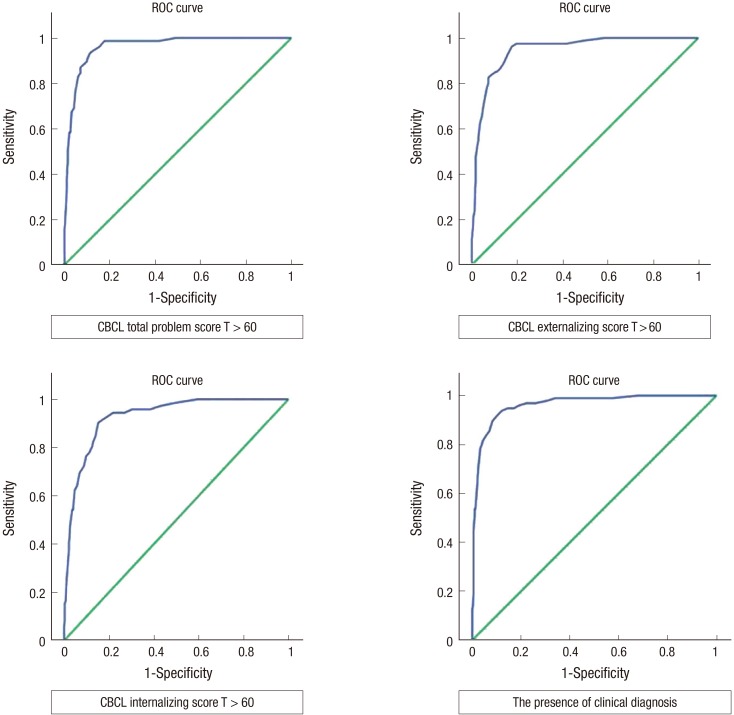

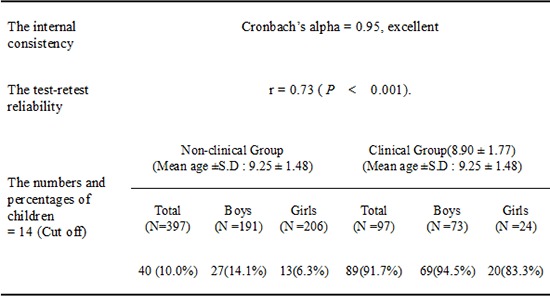

Pediatric symptom checklist-Korean version

The internal consistency of the PSC-Korean version was excellent (Cronbach's alpha=0.95). The test-retest reliability was r=0.73 (P<0.001). However, a poor model fit was observed in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (χ2=1,852.0 at df=554; P<0.001; goodness-of-fit index [GFI]=0.821, adjusted GFI=0.797, root-mean-square error of approximation [RMSEA]=0.069 [90% confidence interval, 0.065-0.072], root-mean-square residual [RMR]=0.015). The mean PSC total scores of the non-clinical and clinical groups were 5.2±6.1 and 27.0±10.1, respectively (F=3.64, P=0.01). The total score of the PSC positively correlated with total CBCL (r=0.85, P<0.01), internalizing score (r=0.73, P<0.01) and externalizing score (r=0.79, P<0.01) (Table 2). Using CBCL scores and experience of the staff at providing psychiatric service, the ROC curve was calculated and is shown in the upper-left corner of Fig. 1. All areas under the ROC curves (AUC) were greater than 0.9 and had statistical significance (Table 3). Using clinical CBCL scores (CBCL total score≥60, CBCL externalizing score≥60, CBCL internalizing score≥60) and presence of clinical diagnosis, the recommended cut-off score of the PSC was 14. Considering the diagnosis made by child and adolescent psychiatrists as the gold standard, the sensitivity and specificity of the PSC-Korean version with a cut-off score of 14 were 91.8% and 89.9%, respectively (Table 4). When using the 28 score cut-off of the USA, 44.3% of the clinical group and 0.5% of the non-clinical group were identified as a risk group with psychosocial problems (13).

Table 2. Scores on the PSC and CBCL for the total problem scale, the internalizing scale and the externalizing scale.

| Variables | Non-clinical group‡ | Clinical group§ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Total (n = 397) | Boys (n = 191) | Girls (n = 206) | Total (n = 97) | Boys (n = 73) | Girls (n = 24) |

| PSC* | 5.2 ± 6.1 | 6.5 ± 6.9 | 4.1 ± 4.9 | 27.0 ± 10.1 | 27.9 ± 10.1 | 24.4 ± 10.9 |

| CBCL† | ||||||

| Total | 42.5 ± 9.4 | 43.1 ± 9.5 | 42.0 ± 9.0 | 61.9 ± 9.7 | 62.2 ± 10.0 | 61.1 ± 9.7 |

| Internalizing | 44.5 ± 9.2 | 44.7 ± 10.1 | 44.2 ± 8.3 | 59.2 ± 10.7 | 59.6 ± 10.9 | 58.2 ± 10.1 |

| Externalizing | 43.3 ± 9.2 | 43.8 ± 9.5 | 42.8 ± 8.9 | 60.6 ± 10.9 | 61.1 ± 10.5 | 59.0 ± 12.2 |

*The difference between the non-clinical group and the clinical group is significant (P<0.001); †Raw CBCL scores were transformed to T-scores; ‡,§One way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used.

Fig. 1. Receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curves using the CBCL score and the presence of clinical diagnosis.

Table 3. The receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curve for possible cut-off values of the Korean version of the PSC using the clinical CBCL score for clinical diagnosis.

| AUC | P value | CI | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL total ≥ 60 | 0.96 | 0.009 | 0.94-0.98 | 10/11 | 98.7 | 80.0 |

| 11/12 | 98.7 | 82.5 | ||||

| 12/13 | 96.1 | 84.6 | ||||

| 13/14 | 94.8 | 86.8 | ||||

| 14/15 | 93.5 | 88.7 | ||||

| 15/16 | 90.9 | 89.9 | ||||

| 16/17 | 89.6 | 90.1 | ||||

| CBCL externalizing ≥ 60 | 0.94 | 0.012 | 0.92-0.96 | 10/11 | 97.5 | 80.2 |

| 11/12 | 96.3 | 82.4 | ||||

| 12/13 | 92.5 | 84.3 | ||||

| 13/14 | 88.8 | 86.0 | ||||

| 14/15 | 86.3 | 87.7 | ||||

| 15/16 | 85.0 | 89.1 | ||||

| 16/17 | 85.0 | 89.6 | ||||

| CBCL internalizing ≥ 60 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.90-0.95 | 10/11 | 94.4 | 76.3 |

| 11/12 | 93.1 | 80.3 | ||||

| 12/13 | 91.7 | 82.7 | ||||

| 13/14 | 90.3 | 84.8 | ||||

| 14/15 | 84.7 | 86.0 | ||||

| 15/16 | 81.9 | 87.2 | ||||

| 16/17 | 80.6 | 87.4 | ||||

| Presence of clinical diagnosis | 0.96 | 0.009 | 0.94-0.98 | 10/11 | 94.8 | 82.9 |

| 11/12 | 94.8 | 85.4 | ||||

| 12/13 | 93.8 | 87.8 | ||||

| 13/14 | 91.8 | 89.9 | ||||

| 14/15 | 89.7 | 91.7 | ||||

| 15/16 | 86.6 | 92.7 | ||||

| 16/17 | 85.6 | 92.9 |

Table 4. The numbers and percentages of children with cut-off scores for the PSC.

| Cut-off scores | Non-clinical | Clinical | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=397) | Boys (n=191) | Girls (n=206) | Total (n=97) | Boys (n=73) | Girls (n=24) | |

| PSC ≥ 14 | 40 (10.0%) | 27 (14.1%) | 13 (6.3%) | 89 (91.7%) | 69 (94.5%) | 20 (83.3%) |

| PSC ≥ 17* | 28 (7.0%) | 20 (10.4%) | 8 (3.8%) | 83 (85.5%) | 65 (89.0%) | 18 (75.0%) |

| PSC ≥ 22† | 10 (2.5%) | 8 (4.1%) | 2 (0.9%) | 69 (71.1%) | 52 (71.2%) | 17 (70.8%) |

| PSC ≥ 28‡ | 2 (0.5%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 43 (44.3%) | 34 (46.5%) | 9 (37.5%) |

*Japanese cut-off; †Dutch cut-off; ‡Original US cut-off.

DISCUSSION

Using 494 Korean children aged 7-12 yr, the current study assessed the reliability and validity of a Korean version of the PSC and suggested a cut-off for recommending further clinical assessment. The results suggest that the Korean version of the PSC has good internal consistency and validity using the standard of CBCL scores.

The internal consistency of the Korean version of the PSC in the current study was excellent (Cronbach's alpha=0.95). The original version of the PSC has also good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.91) (10). In addition, the US version (Cronbach's alpha=0.92), the Spanish version (Cronbach's alpha=0.91) and the Dutch version of the PSC (Cronbach's alpha=0.89) also have been reported to have excellent internal consistency (14,19). The test-retest reliability correlation in the original version of the PSC was r=0.84 - 0.91, and that of the Korean version was r=0.73 (10). Stoppelbein et al. (20) suggested a test-retest reliability (r=0.77) in patients with chronic diseases which is similar to our results. Anastasi et al. (21) reported that a test-retest reliability correlation value higher than 0.70 could be accepted as reasonable.

Factor analysis of the original PSC has found that the measure loads significantly onto three brief subscales for use in identification of attentional, internalizing (depression/anxiety), and conduct problems including the children's depression inventory (CDI) for depression, the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorder (SCARED) for anxiety, and the ADHD scale of the child behavior checklist for attention problems (9,10,13,19). The Korean version of the PSC showed a poor model fit in CFA, as did the Dutch version of the PSC (14). These poor fits may be due to the fact that items on school life had been divided into the factor of internalizing and conduct behaviors. Moreover, different cultural and psychological backgrounds might affect the poor fits compared to those of the original version. However, future studies are needed to verify this conjecture. The correlation between the Korean version of the PSC and the CBCL scores was significant (r≥0.70). These high correlation values suggest that the Korean version of the PSC reveals four latent psychosocial problem dimensions including internalizing, externalizing, attention, and school problems, similar to that proposed by Gardner (18). In ROC curve analysis, AUC values were greater than 0.9. In addition, participants in the clinical group scored significantly higher than those in the non-clinical group. Taken together, these results suggest that the Korean version of the PSC has excellent internal consistency and good reliability and validity.

In a number of validity studies, PSC case classifications agreed with case classifications on the child behavior checklist (CBCL), children's global assessment scale (CGAS) ratings of impairment, and the presence of psychiatric disorder in a variety of pediatric and subspecialty settings representing diverse socioeconomic backgrounds (10,19). When compared to the CGAS in both middle and lower income samples, the PSC has shown high rates of overall agreement (79%; 92%), sensitivity (95%; 88%) and specificity (68%; 100%), respectively (9).

When the clinical cut-off of the PSC-Korean version was set at 28, the detection rate of psychological dysfunction in the non-clinical group was less than 1%. However, this high cut-off only detected 71.1% of children in the clinical group. When the cut-off of the PSC-Korean version was set at 14, the detection rate of psychological dysfunction in the non-clinical group was greater than 10%. Indeed, in an epidemiology study of school-aged children, the detection rate of psychosocial dysfunction was in the range of 12% to 20% (22,23). Studies using the PSC have found prevalence rates of psychosocial impairment in middle class (~12%) that are quite comparable to national estimates of the prevalence of psychosocial problems (10,19). With a cut-off of 14, the detection rate in the clinical group was improved to 91.7% (Table 4). Taken together, these results suggest that the cut-off score for the PSC-Korean version should be 14. Children with psychosocial problems could be also included in the non-clinical group as 40 children (10%) in Table 4. In comparison, the US version of the PSC has a cut-off of 28, the Dutch version has a cut-off of 22 (13,14), the Brazilian version has a cut-off of 21, the Japanese version has a cut-off of 17 and the Mexican version has a cut-off score of 12 (13,14,24,25,26). In the Mexican sample, the PSC has been validated by Mexican-Americans in low-income US communities and the educational level of parents was lower than in our sample (13,17).

When comparing the results of behavioral questionnaires between American and Korean children, the scores of other checklists such as the CBCL, the ADHD rating scale, the child sexual behavior inventory (CSBI), the adolescent dissociative experience scale (A-DES), the child report of post-traumatic symptoms (CROPS) and the parent report of post-traumatic symptoms (PROPS) were lower for Korean children (27,28,29,30,31). Common characteristics of countries with lower scores and lower clinical cut-off recommendations, such as Korea, may be a reflection of real differences in psychological symptoms. However, these scores may also reflect low parental sensitivity to psychological problems (29). Korea is one of the countries in which subjects show a response bias because they want to give an answer that is as socially desirable as possible (28).

There were several limitations in the current research. First, the participant pool was recruited from a small area of Korea, so it may not reflect the entire Korean population. In the clinical group, more males had been recruited and females had been younger in age. Second, the sample could not be screened with a structured clinical interview nor with a clinical global impairment-score. Future studies should consider recruiting from a broad area and including a structured interview and correlation of the scores of subscales of the PSC with the psychiatric diagnosis of patients of child and adolescents. In the clinical group, children with externalizing symptoms such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder were more prevalent (60.9%) compared to those (25.7%) with internalizing disorder such as major depressive disorder, selective mutism and separation anxiety disorder.

The Korean version of the PSC has a good internal consistency and validity using CBCL scores as a standard. Thus, the Korean version of the PSC may be a useful tool for the early detection of psychosocial problems including behavioral and emotional problems in Korean children.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Study design: Chung US. Sampling and data collection: Chung US, Woo J. Data analysis: Chung US, Woo J, Han DH. Writing: Han DH, Chung US, Jung JH, Hwang SY. Revision: Chung US, Han DH. Agreement and submission of final manuscript: All authors.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1026–1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDaniel SH, Grus CL, Cubic BA, Hunter CL, Kearney LK, Schuman CC, Karel MJ, Kessler RS, Larkin KT, McCutcheon S, et al. Competencies for psychology practice in primary care. Am Psychol. 2014;69:409–429. doi: 10.1037/a0036072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durlak JA, Wells AM. Evaluation of indicated preventive intervention (secondary prevention) mental health programs for children and adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26:775–802. doi: 10.1023/a:1022162015815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:355–375. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Niel C, Pachter LM, Wade R, Jr, Felitti VJ, Stein MT. Adverse events in children: predictors of adult physical and mental conditions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35:549–551. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasir A, Watanabe-Galloway S, DiRenzo-Coffey G. Health Services for Behavioral Problems in Pediatric Primary Care. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costello EJ. Primary care pediatrics and child psychopathology: a review of diagnostic, treatment, and referral practices. Pediatrics. 1986;78:1044–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jellinek MS. Sounding board. The present status of child psychiatry in pediatrics. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1227–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198205203062010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Burns BJ. Brief psychosocial screening in outpatient pediatric practice. J Pediatr. 1986;109:371–378. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jellinek MS, Murphy JM. Screening for psychosocial disorders in pediatric practice. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142:1153–1157. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150110031013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagano M, Murphy JM, Pedersen M, Mosbacher D, Crist-Whitzel J, Jordan P, Rodas C, Jellinek MS. Screening for psychosocial problems in 4-5-year-olds during routine EPSDT examinations: validity and reliability in a Mexican-American sample. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1996;35:139–146. doi: 10.1177/000992289603500305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simonian SJ, Tarnowski KJ. Utility of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist for behavioral screening of disadvantaged children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2001;31:269–278. doi: 10.1023/a:1010213221811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Little M, Pagano ME, Comer DM, Kelleher KJ. Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist to screen for psychosocial problems in pediatric primary care: a national feasibility study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:254–260. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reijneveld SA, Vogels AG, Hoekstra F, Crone MR. Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist for the detection of psychosocial problems in preventive child healthcare. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:197. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thun-Hohenstein L, Herzog S. The predictive value of the pediatric symptom checklist in 5-year-old Austrian children. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:323–329. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0494-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Dept. of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H, Oh KJ, Hong KE, Ha EH. Clinical validity study of Korean CBCL through item analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;2:138–149. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner W, Pajer KA, Kelleher KJ, Scholle SH, Wasserman RC. Child sex differences in primary care clinicians' mental health care of children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:454–459. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.5.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy JM, Ichinose C, Hicks RC, Kingdon D, Crist-Whitzel J, Jordan P, Feldman G, Jellinek MS. Utility of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist as a psychosocial screen to meet the federal Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) standards: a pilot study. J Pediatr. 1996;129:864–869. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoppelbein L, Greening L, Jordan SS, Elkin TD, Moll G, Pullen J. Factor analysis of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist with a chronically ill pediatric population. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:349–355. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200510000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anastasi A, Urbina S. Psychological testing. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costello EJ, Costello AJ, Edelbrock C, Burns BJ, Dulcan MK, Brent D, Janiszewski S. Psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care. Prevalence and risk factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1107–1116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360055008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandenburg NA, Friedman RM, Silver SE. The epidemiology of childhood psychiatric disorders: prevalence findings from recent studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:76–83. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishizaki Y, Fukai Y, Kobayashi Y, Ozawa K. Validation and cutoff score of the Japanese version of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist: screening of school-aged children with psychosocial and psychosomatic disorders. J Jpn Pediatr Soc. 2000;104:831–840. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jutte DP, Burgos A, Mendoza F, Ford CB, Huffman LC. Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist in a low-income, Mexican American population. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:1169–1176. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crijnen AA, Achenbach TM, Verhulst FC. Comparisons of problems reported by parents of children in 12 cultures: total problems, externalizing, and internalizing. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1269–1277. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muzzolon SR, Cat MN, dos Santos LH. Evaluation of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist as a screening tool for the identification of emotional and psychosocial problems. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2013;31:359–365. doi: 10.1590/S0103-05822013000300013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogler LH. The meaning of culturally sensitive research in mental health. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:296–303. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin Y, Chung US, Jeong SH, Lee WK. The reliability and validity of the korean version of the child sexual behavior inventory. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10:336–345. doi: 10.4306/pi.2013.10.4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee KM, Jeong SH, Lee WK, Chung US. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the child report of post-traumatic symptoms (CROPS) and the parent report of post-traumatic symptoms (PROPS) J Korean Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;22:169–181. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin JU, Jeong SH, Chung US. The Korean Version of the Adolescent Dissociative Experience Scale: Psychometric Properties and the Connection to Trauma among Korean Adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2009;6:163–172. doi: 10.4306/pi.2009.6.3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]