Abstract

Vasospasm (VSP) is one of the major causes for prolonged neurologic deficit in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Few case series have reported about continuous local intra-arterial nimodipine administration (CLINA) in refractory VSP. We report our experience with CLINA in a patient with refractory cerebral VSP.

Keywords: aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, intra-arterial nimodipine, transcranial color-coded sonography, vasospasm

Introduction

Vasospasm (VSP) is one of the major causes for prolonged neurologic deficit in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.1 Treatment of VSP is therefore one of the main priorities for these patients. Balloon angioplasty or stenting are options for VSP of the proximal vessels, whereas distally located VSP is preferably treated pharmacologically.2 A long list of pharmacologic agents has been tested for their effect on VSP. Intravenous (IV) or oral application of nimodipine combined with triple H therapy (hypertension, hypervolemia, hemodilution) is currently recommended as the first-line prevention for VSP.3 In patients not responding to this preventive therapy, short local intra-arterial nimodipine administration (SLINA) is recommended, although it is often only effective during the time of infusion.4 However, intra-arterial (IA) nimodipine administration may be prolonged for a few days. Few case series have reported about the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of this treatment, and standardized guidelines are lacking.5 6 7 8

We report our experience with continuous local intra-arterial nimodipine administration (CLINA) via a catheter in the internal carotid artery (ICA) in refractory cerebral VSP.

Case Report

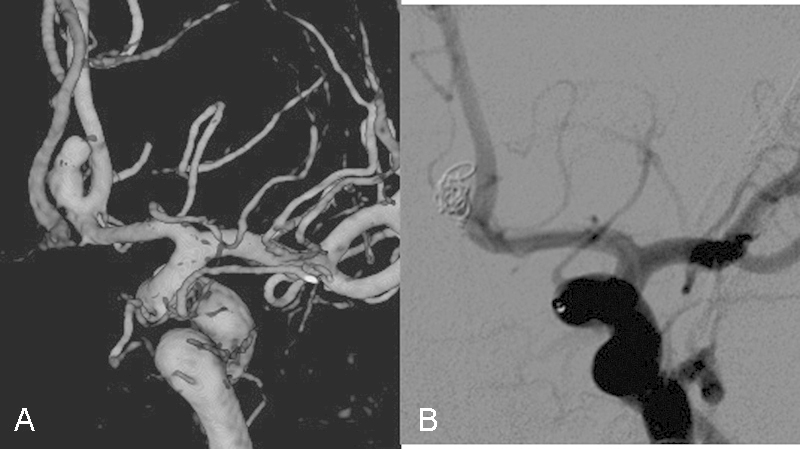

A 40-year-old woman was referred to our hospital due to headache and nausea that started acutely the day of admission. She had no history of hypertension or other diseases but was a former smoker. Native computed tomography (CT) scan showed a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) extending to the suprasellar cisterns and both Sylvian fissures (modified Fisher grade 4). The Hunt & Hess grade was 2, and the Glasgow Coma Scale and the World Federation of Neurosurgery grade were 15 and 1, respectively. CT angiography (CTA) revealed a saccular aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery (ACom) (Fig. 1). The patient had an anatomical variant with three small ACom segments. The aneurysm was located at the most distal ACom segment, at the origin of the left anterior cerebral artery A2 segment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Three-dimensional angiography of left carotid artery showing an anterior communicating artery aneurysm measuring 3 × 7 mm. (B) The aneurysm was completely occluded after coiling. No vasospasm was seen.

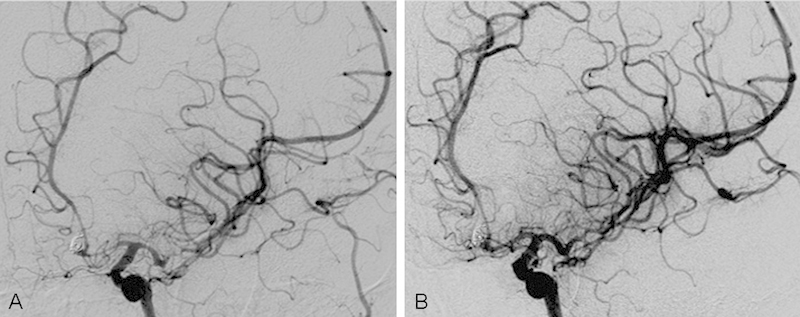

The aneurysm was successfully treated by coil embolization, and the patient was asymptomatic after the procedure. According to the department's standard post-SAH treatment protocol, the patient was given continuous IV nimodipine, fluids, and statins. At day 6, the patient developed hemiparesis predominantly affecting the right arm and severe expressive aphasia corresponding to a National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 6 (facial palsy 1; arm 2; leg 1, aphasia 2). CTA showed VSP in the intracranial ICA, the anterior cerebral artery proximal segment (A1), and the middle cerebral artery proximal segment (M1) bilaterally, but predominantly on the left side. VSP was present also in the basilar artery and the left posterior cerebral artery. At day 7, 30-minute IA administration of 4 mg nimodipine in the left intracranial ICA and 30 minute IA administration of 4 mg nimodipine in the left intracranial vertebral artery led to a clear improvement of angiographic VSP and neurologic impairment. Due to the recurrence of symptoms at day 8, 30-minute IA administration of 4 mg nimodipine in the left intracranial ICA and in the left intracranial vertebral artery were repeated with beneficial but transitory effect. At day 9, 1 hour IA administration of 8 mg nimodipine followed by 3-minute IA administration of 30 mg papaverine were performed. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed partial resolution of VSP in the left M1 and A1 but persistent VSP in the left M2 and A2 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Left carotid angiogram at the initiation of continuous local intra-arterial (IA) nimodipine infusion day 9 (three short local IA nimodipine administrations were done on days 7, 8, and 9 after coil embolization). (A) Severe vasospasm is seen in the A1, A2, and M2 branches. (B) Partial resolution after 4 mg nimodipine in 30 minutes but still severe vasospasm in A2.

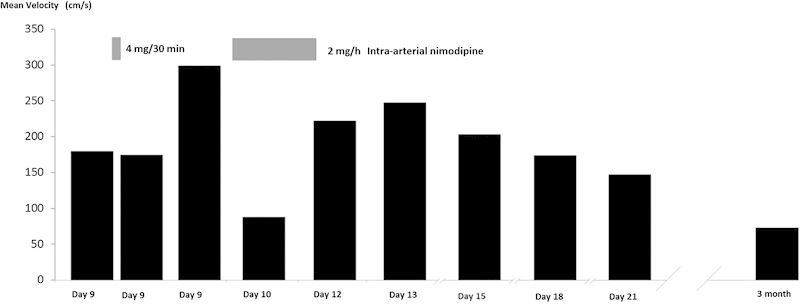

Transcranial color-coded sonography (TCCS) measurements of blood flow velocity in the left distal M1 showed no changes before and after IA treatment (Fig. 3). Two hours later, cerebral MRI showed multiple watershed infarcts in the left carotid artery territory and in the left parietal lobe (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Mean velocity in the left distal M1 segment measured with transcranial color-coded sonography.

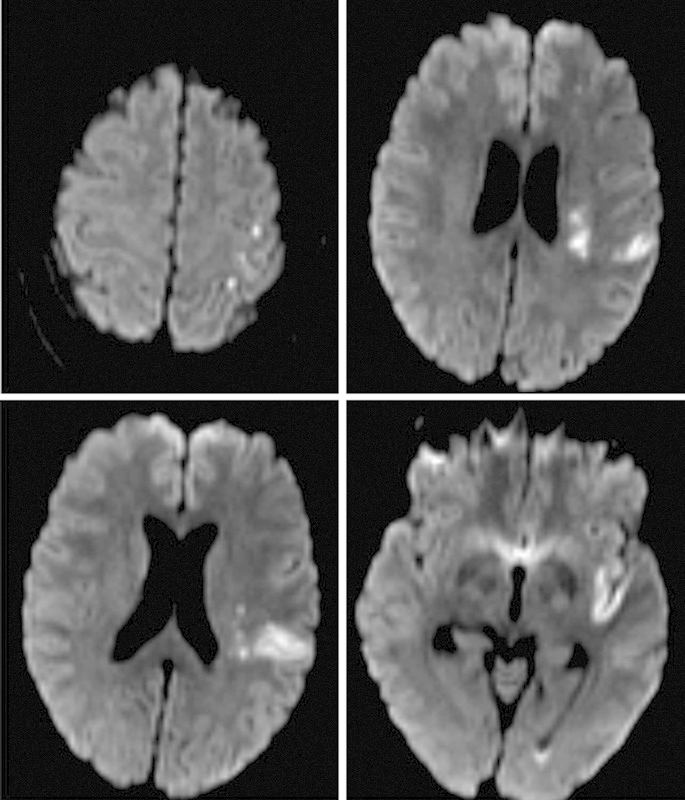

Fig. 4.

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging day 9 showed scattered cortical infarctions in the left hemisphere.

The patient was quickly referred to TCCS that showed marked worsening of hemodynamics (mean velocity of 300 cm/s in the left distal M1, Lindegaard index > 7). DSA was therefore repeated and confirmed severe VSP in the left M1 and A1. CLINA was established by introducing a microcatheter (Progreat 2.7F, Terumo Interventional System, Tokyo, Japan) into the left ICA through a guiding catheter. With the microcatheter in place, the guiding catheter was pulled back into the aortic arch. Nimodipine dose was set at 2 mg/h. An IV bolus dose of 5000 IE heparin was administered initially, followed by 1500 to 2500 units/h to keep the activated clotting time >200 s.

A few hours later, the patient showed improvement of symptoms with normalized motor function and only a slight residual aphasia (NIHSS = 1). At day 10, TCCS showed a dramatic improvement of the hemodynamic parameters (Fig. 3).

At day 12, CLINA was stopped, the catheter and the sheath were removed, and the full dosage (2 mg/h) was given IV for 7 days and then orally for another 7 days. In addition to nimodipine, advanced VSP treatment including pressor, fluids, statins, magnesium, and dantrolene was administered.

During the hospital stay a lumbar drain was inserted due to transient hydrocephalus, and antibiotics were given due to a urinary tract infection. No other complications were reported. The patient was discharged at day 22 and transferred to a local hospital. She had no measurable speech impairment but a slight disturbance of fine motor skills in the right hand, and she complained about gait instability and dysesthesia in the right hemibody (NIHSS = 0). At follow-up day 90, the patient reported reduced stamina, mild headache, and non–drug-demanding neuropathic pain in the right arm. Motor function was normalized, and she had no apparent speech impairment (NIHSS = 0). Modified Rankin Scale score was 2, and Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale was 5. TCCS showed normal blood flow velocities in all intracranial arteries, and MRI showed no new ischemic lesions.

Discussion

This is the first case of continuous local intra-arterial nimodipine administration (CLINA) for refractory VSP described in Scandinavia. The treatment had a dramatic effect on both angiographic VSP and neurologic impairment with no complications. In line with earlier reports,5 6 7 8 9 10 our case shows that CLINA is feasible, safe, and may be effective in patients with symptomatic medically refractory VSP following SAH.

However, there is no consensus when to start the treatment. Although other reports recommend starting CLINA if 30-minute IA nimodipine administration does not show improvement of VSP, the threshold for referring patients to DSA is not always specified. In some earlier reports, patients were referred to DSA either after a decline in the parameters of multimodal neuromonitoring or after progressive loss of consciousness postoperatively.5 7 8 In another report, the patients underwent DSA within the first 2 hours after onset of clinical symptoms and decrease in brain tissue oxygen.6 In our patient, CLINA was started 2 days after the first focal neurologic impairment. The two SLINAs performed at day 7 and day 8 showed good angiographic response and partial clinical improvement. The third SLINA showed partial resolution of angiographic VSP with no clinical and Doppler response, and MRI showed established cerebral infarction. In an earlier study, 21 of 25 patients treated with CLINA developed cerebral infarction secondary to VSP,7 and, similarly to our case, the mean onset of CLINA was 9.19 ± 3.31 days. In another case series of 6 patients, onset of CLINA was 7.5 ± 2.06 days, and none of the patients had cerebral infarction.6

Due to the possibly high safety profile and efficacy of the treatment, it may therefore be appropriate to refer patients promptly to DSA and CLINA in case of development of focal neurologic impairment6 to prevent ischemic complications. Transcranial ultrasound has a high specificity (99%) and positive predictive value (97%) for the detection of VSP in the middle cerebral artery11 and is of established value in the detection and monitoring of VSP after SAH (strong recommendation, class I–II evidence).12 13 In our case, there was a good correlation between ultrasonographic findings, clinical impairment, and DSA. Future studies should investigate if TCCS may play a major role in the early selection of patients who will benefit from this treatment.

CLINA has some limitations. There are no standardized guidelines for patient selection, the start and the duration of CLINA, as well as for the dosage of nimodipine and heparin. CLINA is an expensive and resource-demanding procedure requiring specialized intensive care with a multidisciplinary team of anesthesiologists, neuroradiologists, neurosurgeons, and the availability of multimodal neurologic monitoring. Wall dissection, catheter dislocation, sepsis, air emboli, and embolic infarction due to thrombotic adhesion at catheter or vessel wall are all potential complications of CLINA. Moreover, a too high nimodipine dose may lead to hypotension, whereas inappropriate heparin dosage may lead to either thromboembolic or hemorrhagic complications. None of the earlier studies has reported complications.5 6 7 8 However, there are no conclusive data about the safety of CLINA because all the current evidence is based on case series that may be affected by publication bias.

In conclusion, our case report adds new evidence on the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of CLINA. Further studies are needed to clarify if transcranial ultrasound or other modalities such as MR and/or CT perfusion are able to early select which patients are likely to profit from CLINA.

References

- 1.Kassell N F, Sasaki T, Colohan A R, Nazar G. Cerebral vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1985;16(4):562–572. doi: 10.1161/01.str.16.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisman J L, Eskridge J M, Newell D W. Neurointerventional treatment of vasospasm. Neurol Res. 2006;28(7):769–776. doi: 10.1179/016164106X152043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorhout Mees S M, Rinkel G J, Feigin V L. et al. Calcium antagonists for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18(3):CD000277. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000277.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biondi A, Ricciardi G K, Puybasset L. et al. Intra-arterial nimodipine for the treatment of symptomatic cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: preliminary results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(6):1067–1076. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer T E, Dichgans M, Straube A. et al. Continuous intra-arterial nimodipine for the treatment of cerebral vasospasm. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31(6):1200–1204. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musahl C, Henkes H, Vajda Z, Coburger J, Hopf N. Continuous local intra-arterial nimodipine administration in severe symptomatic vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(6):1541–1547; discussion 1547. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31820edd46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott S, Jedlicka S, Wolf S. et al. Continuous selective intra-arterial application of nimodipine in refractory cerebral vasospasm due to aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:970741. doi: 10.1155/2014/970741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf S, Martin H, Landscheidt J F, Rodiek S O, Schürer L, Lumenta C B. Continuous selective intraarterial infusion of nimodipine for therapy of refractory cerebral vasospasm. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12(3):346–351. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand S, Goel G, Gupta V. Continuous intra-arterial dilatation with nimodipine and milrinone for refractory cerebral vasospasm. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014;26(1):92–93. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31829bcde1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doukas A, Petridis A K, Barth H, Jansen O, Maslehaty H, Mehdorn H M. Resistant vasospasm in subarachnoid hemorrhage treated with continuous intraarterial nimodipine infusion. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 2011;112:93–96. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0661-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lysakowski C, Walder B, Costanza M C, Tramèr M R. Transcranial Doppler versus angiography in patients with vasospasm due to a ruptured cerebral aneurysm: a systematic review. Stroke. 2001;32(10):2292–2298. doi: 10.1161/hs1001.097108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diringer M N, Bleck T P, Claude Hemphill J III. et al. Critical care management of patients following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: recommendations from the Neurocritical Care Society's Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15(2):211–240. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloan M A, Alexandrov A V, Tegeler C H. et al. Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Assessment: transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2004;62(9):1468–1481. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.9.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]