Abstract

Extraneural metastatic disease resulting from a primary central nervous system neoplasm is a rare clinical finding in the pediatric population. We report a case of peritoneal glioblastoma carcinomatosis following placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt and chemoradiotherapy in a 6-year-old female patient who initially presented with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. This case demonstrates the importance of evaluation of extraspinal structures when imaging for extension of disease. Additionally, this report highlights the cross-sectional imaging characteristics of glioblastoma peritoneal carcinomatosis and presents additional information that will facilitate the timely diagnosis of extraneural metastases of primary high-grade glial neoplasms in the pediatric population.

Keywords: pontine glioma, peritoneal metastasis, magnetic resonance imaging, pediatrics

Introduction

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is an aggressive primary glial neoplasm that accounts for 15% of all childhood brain tumors and is the primary cause of brain tumor–related deaths in children.1 The median survival for patients with DIPG remains < 12 months following initial diagnosis.1 Historically, the treatment planning was based on a radiographic diagnosis, with tissue sampling reserved for radiographically atypical cases. Three decades of clinical trials using this diagnostic approach for eligibility has failed to achieve any improvement in survival.1 Modern surgical experience suggests that tissue sampling is feasible in DIPG patients, and the utility of tissue for diagnosis and biologic target–directed treatment is currently under investigation.2

In this patient population, surgical insertion of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunt into the peritoneum is commonly performed to relieve the symptoms of obstructive hydrocephalus that inevitably occur. The development of metastatic disease from primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors outside of the craniospinal axis directly resulting from this procedure is a relatively rare event, occurring in < 0.5% of a large autopsy series.3 However, with the current life-prolonging treatment strategies for pediatric CNS neoplasms, a concomitant increase in the incidence of extraneural metastatic disease is expected to occur.

Observations

A 6-year-old girl presented to our institution in January 2011 with a short history of ataxia and right-sided facial nerve palsy with superimposed symptoms of increased intracranial pressure. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain demonstrated an expansile, nonenhancing, T2 hyperintense mass centered within the pons with associated obstructive hydrocephalus (Fig. 1A–C). MR image-guided tissue sampling of the mass revealed a World Health Organization grade 3 anaplastic astrocytoma. A right frontal ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt was surgically inserted to alleviate the symptoms of obstructive hydrocephalus. Following initial tissue sampling, the patient began a phase II clinical trial (PBTC-030) in which she was treated with capecitabine and concomitant external-beam radiation therapy. A total dose of 55.8 Gy (1.8 Gy fractionated daily) was administered to the tumor volume. The patient demonstrated transient clinical improvement while on this therapeutic regimen, completed in June 2011.

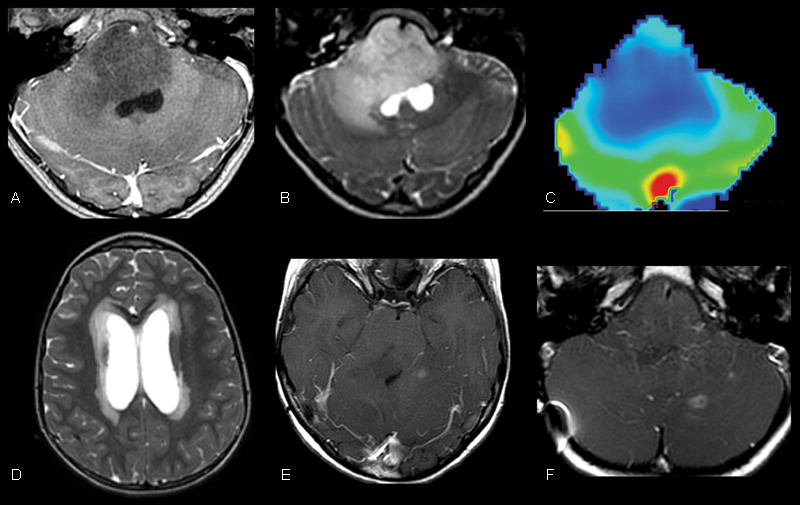

Fig. 1.

Initial magnetic resonance imaging of our patient demonstrated a grade 3 anaplastic astrocytoma centered within the pons. (A, B) T1 postcontrast and T2-weighted images demonstrate an expansile, nonenhancing, T2 hyperintense mass centered within the pons. (C) Dynamic T2* susceptibility weighted contrast-enhanced cerebral blood volume map demonstrates no evidence of increased cerebral blood volume within the pons consistent with the provided diagnosis. (D) Axial T2-weighted image through the level of the lateral ventricles demonstrates hydrocephalus with transependymal flow of cerebrospinal fluid resulting from the mass effect of the lesion in the midbrain. (E, F) Follow-up surveillance imaging after medial and radiation therapy demonstrates rim-enhancing foci within the supra- and infratentorial brain that suggested the progression of disease.

Surveillance MR imaging of the brain demonstrated progression of disease in December 2011 and February 2012 manifested by the development of multifocal supratentorial and infratentorial enhancing lesions (Fig. 1D, E) in the setting of progressive tandem gait deficit.

She was subsequently started on a new phase I clinical trial (PBTC-031) in which she was treated with vascular endothelial growth factor pathway inhibitor (PTC-299); however, despite tolerating the treatment regiment well, the patient subsequently demonstrated progression of disease. In March 2012, the patient began treatment with Temodar (temozolomide) but again demonstrated progression of disease, and in April 2012, she received a second course of radiation therapy to the sites of intraparenchymal metastases (24 Gy total dose; 2 Gy fractions to regions with tumor recurrence). Therapy to the primary brainstem lesion was also augmented. The patient demonstrated significant clinical improvement after reirradiation and was followed with surveillance MR imaging.

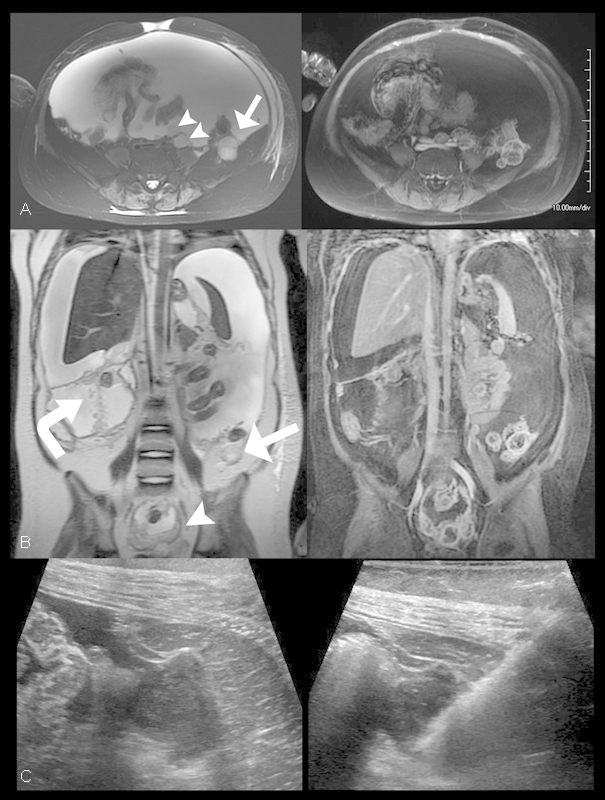

The patient was admitted to our institution in November 2012 when she developed worsening hydrocephalus, urinary incontinence, and abdominal bloating. VP shunt revision was performed. MR imaging of the total spine performed to assess for spinal metastases demonstrated a small left paracolic mass with associated ascites. Subsequent MR imaging of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated diffuse, T2 hyperintense, heterogeneously enhancing peritoneal masses with large volume ascites (Fig. 2A, B). Nodular masses were also noted to coat the surface of the VP shunt catheter along its intraperitoneal course, which resulted in the formation of a nodular bridge between the omentum and anterior abdominal wall at the site of shunt entry. An intra-abdominal primary source for peritoneal carcinomatosis was not identified. Bedside ultrasound-guided tissue sampling of the left paracolic mass demonstrated glioblastoma histopathologically (Fig. 2C and Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Glioblastoma peritoneal carcinomatosis. (A, B) Axial and coronal T2 (left) and T1-weighted fat-saturated postcontrast (right) images through the abdomen and pelvis demonstrates multiple foci of T2 hyperintense enhancing peritoneal tissue nodules (arrowheads) the largest of which was located posterior to the left colon about the Iliacus muscle (arrow) with associated large-volume ascites. Additionally, the VP shunt catheter course was noted to be studded with nodular enhancing foci (curved arrow). (C) Axial pre (left) and post (right) biopsy sonographic images through the left lower quadrant of the abdomen demonstrates the previously observed left paracolic mass anterior to the left Iliacus muscle characterized by predominantly hypoechoic features. The hyperechoic linear lesion corresponds to the core biopsy needle within the mass during ultrasound-guided tissue sampling.

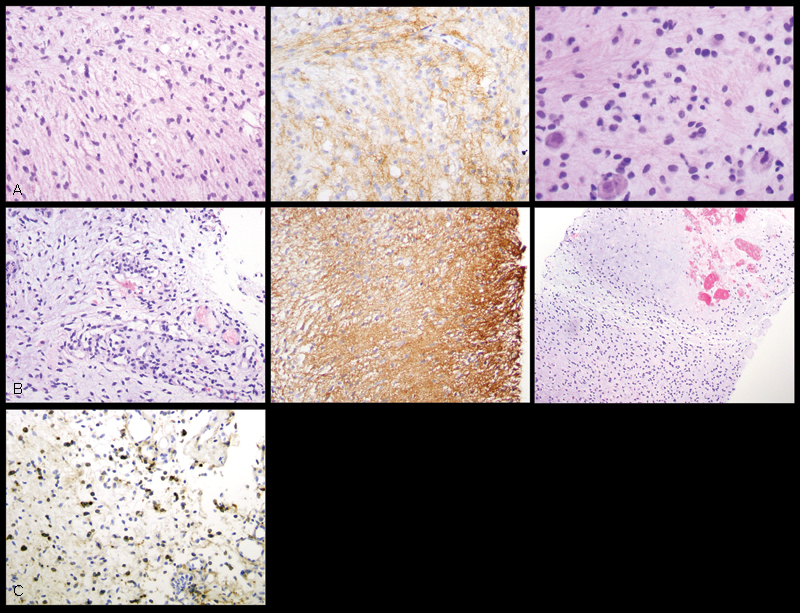

Fig. 3.

Histologic and immunohistochemical (200× total magnification) features of the patient's peritoneal tumor are most consistent with metastatic glioblastoma. (A) At the time of diagnosis, tissue sampling of the patient's brainstem lesion showed a diffusely infiltrating astrocytic neoplasm (top left) positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (top middle), with scattered mitotic figures (top right), consistent with anaplastic astrocytoma, World Health Organization (WHO) grade III. (B) Tissue specimen of the patient's peritoneal tumor showed spindled cells with hyperchromatic and mildly to moderately atypical nuclei in a myxoid background (middle left), closely resembling the patient's primary intracranial tumor. GFAP positivity confirmed the astrocytic lineage of the neoplastic cells (middle). Foci of microvascular proliferation and areas suspicious for necrosis (middle right) indicated progression of the patient's disease to glioblastoma, WHO grade IV. (C) Epidermal growth factor receptor immunohistochemical staining demonstrates positive tumor expression (brown stained cells).

Following the diagnosis of glioblastoma peritoneal carcinomatosis, a peritoneal drain was placed for palliative relief of the large-volume ascites. A 5-day course of temozolomide followed by erlotinib maintenance resulted in the patient's improved mental status; however, surveillance imaging in January 2013 again demonstrated progression of disease throughout the brain and abdomen. The patient died in March 2013, 26 months following the initial diagnosis.

Conclusions

Previous investigators have reported the propensity for primary pediatric glial neoplasms to metastasize to the peritoneum via VP shunt catheter. A review of the literature demonstrates glioma dissemination through VP shunts is a rare occurrence (Table 1). Large autopsy studies have estimated the incidence of extraneural spread of primary high-grade glioma to be 0.47%.4 Rickert identified 245 reported cases of extraneural metastases occurring in patients < 18 years of age.5 Of this cohort, 67 cases (27.3%) were directly related to VP shunt placement with 5 cases attributed to glioblastoma metastasis. Glioma dissemination was previously reported through ventriculoperitoneal, ventriculoatrial, and ventriculopleural CSF shunts.1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Table 1. Literature review.

| Study | Age and gender | Tumor | Treatment | Shunt | Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollack et al6 | 6-MO M | Benign astrocytoma | GTR, CX, RT | V-Per | Metastatic astrocytoma in peritoneal cavity |

| Trigg et al7 | 3½-YO M | Optic glioma | STR, RT, CX | V-Per | Malignant ascites |

| Rickert9 | 3 M, 1 F (mean age: 2.3 y) 1 M, 1 F (mean age: 11.0 y) |

Astrocytoma Glioblastoma |

Not discussed | V-Per | Abdominal metastases |

| Jiménez-Jiménez et al11 | 4-YO F | Brainstem astrocytoma | RT, CX | V-Per | Ascites and spinal cord seeding |

| Jacques et al15 | 13-YO F | Enhancing pontine glioma | Bx, RT | V-Per → V-A | Malignant ascites |

| Kumar et al15 | 9-YO M | Thalamic glioblastoma | STR, RT | V-Per | Malignant ascites |

| Newton et al16 | 13-YO M | Pontine glioblastoma | Bx, CX, RT | V-Per | Ascites with metastatic deposits in the omentum |

| Wakamatsu et al17 | 22-YO M | Medullary glioblastoma | RT | V-Pl → V-A | Tumor cell growth in right pleural cavity |

Abbreviations: Bx, biopsy; CX, chemotherapy; F, female; GTR, gross total resection; M, male; MO, month old; RT, radiation therapy; V-A, ventriculoatrial; V-Per, ventriculoperitoneal; V-Pl, ventriculopleural; YO, year old.

Despite its rare occurrence, metastasis of primary glial neoplasms via shunt catheter to the peritoneal cavity is expected to increase with improved medical, surgical, and radiation therapies.3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Previous investigators have hypothesized that the underlying etiology of primary CNS glial neoplasm spread via the cerebrospinal pathways is through shedding of neoplastic cells into the CSF.11 12 In our case, we hypothesize that the VP shunt catheter served as a conduit through which neoplastic cells were delivered from the ventricular system into the peritoneal cavity. Although we have no objective evidence of the VP shunt acting as a pathway for metastatic spread, other routes (hematogenous or lymphatic) are thought to be less likely given the patient's imaging findings.

A paucity of literature about the sonographic and MR imaging characteristics of glioblastoma peritoneal carcinomatosis currently exists. In the present case, the metastatic peritoneal implants were T2 and short tau inversion recovery hyperintense, T1 isointense, peripherally rim enhancing following the administration of intravenous gadolinium-based contrast, and without reduced diffusion. Sonographic imaging of the peritoneal lesions demonstrated nonspecific hypoechoic masses.

The unequivocal clinical diagnosis of extraneural primary glioma metastatic disease is based on the Weiss criteria, developed in 1955, which suggests four criteria should be observed: (1) the metastatic lesion must be histologically characteristic of a CNS tumor, (2) the clinical history must indicate that initial symptoms were due to the CNS tumor, (3) the morphologic features of the primary lesion and metastatic lesion must be identical, and (4) a complete autopsy must be performed to exclude the possibility of any other primary tumor.13 Although the impact of reirradiation on survival is not known, our patient survived > 1 year beyond the expected median survival for DIPG, and her more prolonged survival may have allowed for malignant transformation from anaplastic astrocytoma to glioblastoma with dissemination.

This case report and literature review suggests that there is a risk of peritoneal carcinomatosis of glioblastoma in the setting of VP shunt placement. Given the known risk of shunt spread of disease from the CNS, informed consent for shunt placement should include this possible long-term complication. Moreover, when abdominal symptoms arise in the setting of an indwelling VP shunt, this rare diagnosis should be considered during cross-sectional evaluation (ultrasound, computed tomography, MRI). In the absence of clinical symptoms, the rarity of this complication probably does not warrant routine imaging surveillance. The recognition of metastatic disease outside of the craniospinal axis in patients with primary CNS tumors is important to the overall disease course because the timely administration of medical therapy may improve clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks Bethany Barajas for her helpful comments regarding this manuscript.

Funding This work was funded by the University of California San Francisco, Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging. This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (5T32EB001631–07).

Note

Ramon Francisco Barajas Jr. and Andrew Phelps contributed equally.

References

- 1.Khatua S, Moore K R, Vats T S, Kestle J R. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma—current status and future strategies. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27(9):1391–1397. doi: 10.1007/s00381-011-1468-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cage T A, Samagh S P, Mueller S. et al. Feasibility, safety, and indications for surgical biopsy of intrinsic brainstem tumors in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(8):1313–1319. doi: 10.1007/s00381-013-2101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duffner P K, Cohen M E. Extraneural metastases in childhood brain tumors. Ann Neurol. 1981;10(3):261–265. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuster H, Jellinger K, Gund A, Regele H. Extracranial metastases of anaplastic cerebral gliomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1976;35(4):247–259. doi: 10.1007/BF01406121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rickert C H. Extraneural metastases of paediatric brain tumours. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;105(4):309–327. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0666-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollack I F, Hurtt M, Pang D, Albright A L. Dissemination of low grade intracranial astrocytomas in children. Cancer. 1994;73(11):2869–2878. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2869::aid-cncr2820731134>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trigg M E, Swanson J D, Letellier M A. Metastasis of an optic glioma through a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Cancer. 1983;52(4):599–601. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830815)52:4<599::aid-cncr2820520403>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schweitzer T, Vince G H, Herbold C, Roosen K, Tonn J C. Extraneural metastases of primary brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2001;53(2):107–114. doi: 10.1023/a:1012245115209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rickert C H. Abdominal metastases of pediatric brain tumors via ventriculo-peritoneal shunts. Childs Nerv Syst. 1998;14(1-2):10–14. doi: 10.1007/s003810050166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger M S, Baumeister B, Geyer J R, Milstein J, Kanev P M, LeRoux P D. The risks of metastases from shunting in children with primary central nervous system tumors. J Neurosurg. 1991;74(6):872–877. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.6.0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiménez-Jiménez F J, Garzo-Fernández C, De Inovencio-Arocena J, Pérez-Sotelo M, Castro-De Castro P, Salinero-Paniagua E. Extraneural metastases from brainstem astrocytoma through ventriculoperitoneal shunt. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54(3):281–282. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liwnicz B H, Rubinstein L J. The pathways of extraneural spread in metastasizing gliomas: a report of three cases and critical review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1979;10(4):453–467. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(79)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss L. A metastasizing ependymoma of the cauda equina. Cancer. 1955;8(1):161–171. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1955)8:1<161::aid-cncr2820080123>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontanilla H P, Pinnix C C, Ketonen L M. et al. Palliative reirradiation for progressive diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35(1):51–57. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318201a2b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacques T S, Miller K, Rampling D, Gatscher S, Harding B. Peritoneal dissemination of a malignant glioma. Cytopathology. 2008;19(4):264–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar R, Jain R, Tandon V. Thalamic glioblastoma with cerebrospinal fluid dissemination in the peritoneal cavity. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;31(5):242–245. doi: 10.1159/000028870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newton H B, Rosenblum M K, Walker R W. Extraneural metastases of infratentorial glioblastoma multiforme to the peritoneal cavity. Cancer. 1992;69(8):2149–2153. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920415)69:8<2149::aid-cncr2820690822>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakamatsu T, Matsuo T, Kawano S, Teramoto S, Matsumura H. Glioblastoma with extracranial metastasis through ventriculopleural shunt. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1971;34(5):697–701. doi: 10.3171/jns.1971.34.5.0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]