Abstract

Objective

To assess the prevalence and pathological nature of incidental focal thyroid uptake on 18F-FDG (2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose) PET (positron emission tomography) and examine the role of the maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) to differentiate benign from malignant thyroid pathology.

Material and Methods

18F-FDG PET reports were retrospectively reviewed. Incidental focal tracer uptake in the thyroid was noted in 147 patients (0.5%). Patients with known primary thyroid malignancy were excluded. The final diagnosis was made following ultrasonography of the neck, fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or histopathology of the surgically resected specimen where surgery was indicated. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the SUVmax of benign and malignant thyroid pathology. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to identify an SUVmax cutoff in differentiating benign from malignant pathology.

Results

A final diagnosis was achieved in 47/147 (32%) of the patients. The diagnoses included benign lesions in 36 patients and malignancy in 9 patients. In 2 patients, FNAC demonstrated indeterminate follicular lesions; however, surgical excision was not performed. There was a highly significant difference in the mean SUVmax of malignant focal thyroid uptake (15.7 ± 5.9) compared to that of benign lesions (7.1 ± 6.8) with a p value of 0.000123. An SUVmax of 9.1 achieved a sensitivity of 81.6%, specificity of 100% and area under the curve of 0.915 in the ROC analysis differentiating benign from malignant disease.

Conclusion

The malignancy potential of incidental focal thyroid uptake remains high and warrants prompt and appropriate follow-up by the clinician. The SUVmax may aid in further characterisation of the lesion and its management.

Key Words: Thyroid, Uptake, 18F-FDG, PET

Introduction

The prevalence of thyroid nodules in the general population is high and is reported to be between 8 and 65% [1]. Due to the significant advances in imaging technology and the increased use of neck imaging, detection of unsuspected thyroid nodules, known as incidentalomas, is on the rise.

18F-FDG (2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose) PET/CT (positron emission tomography/computed tomography) has been increasingly used for assessment of various malignancies and plays an integral role in cancer management. 18F-FDG is a glucose analogue and the mechanism of 18F-FDG uptake and detection of tumours is based on the higher glycolytic metabolism and the higher expression of membrane glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins in the malignant tissue [2]. Incidental diffuse and focal thyroid uptake is often seen on 18F-FDG PET/CT study. Diffuse uptake in the thyroid has been reported in approximately 0.6-3.3% of the 18F-FDG PET studies and is often due to a benign aetiology [3]. The prevalence of focal uptake within the thyroid (incidentaloma) on 18F-FDG PET has been noted to range from 0.2 to 10.1% in various studies. This is clinically more significant due to its high risk of malignancy in these lesions and the reported risk of malignancy is varied (8-64%) [4]. Malignancy identified within the thyroid incidentaloma on 18F-FDG PET has been noted to be of a higher grade/aggressive subtype [5], requiring prompt evaluation by the clinician. This may create a management dilemma for the referring clinicians [6].

The maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) assessed by 18F-FDG PET is a semi-quantitative measure of glucose metabolism, which is useful in the estimation of tumour grade or aggressiveness and as a marker in assessment of response to treatment. It is defined as the maximum uptake in the lesion scaled by the administered activity and patient weight or height [7]. Some studies claim a beneficial role of the SUVmax in differentiating benign from malignant thyroid pathology, but this has not been replicated in other studies and therefore remains controversial [8,9].

The aim of this study was to assess the pathological nature of the focal thyroid incidentalomas detected on 18F-FDG PET and the role of the SUVmax in differentiation of benign from malignant thyroid pathology in these patients.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study reviewing 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT scan reports of 29,300 studies performed in the nuclear medicine department at our institution between January 1999 and December 2013 for various oncological and non-oncological indications. Institutional review board approval was obtained for the study.

The search criteria ‘uptake in the thyroid’ was applied to these scan reports, which provided 147 results as having incidental focal tracer uptake in the thyroid. Patients with an established diagnosis of a malignant primary thyroid neoplasm were excluded from the analysis. Data including age, sex, primary malignancy site, indication for the PET study and the SUVmax of the focal thyroid uptake were recorded.

PET/CT imaging was performed 60 min after injection of 18F-FDG (5 MBq/kg of body weight). Standard patient preparation prior to the study included a fasting period of at least 4-6 h and a serum glucose level <7 mmol/l (120 mg/dl) before 18F-FDG administration.

The PET scan report in patients with a focal uptake in the thyroid gland recommended further evaluation of the uptake with ultrasonography (USG) with and without fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and where appropriate referral to the head and neck, endocrinology or endocrine surgery teams for further management. The final diagnosis for the focal thyroid incidentalomas was made by USG of the neck, FNA cytology (FNAC) or histopathology of the surgically resected specimen, where available. The prevalence of thyroid incidentalomas on 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT and the rate of malignancy in focal uptake were assessed. The SUVmax of focal uptake was noted in patients with a focal thyroid incidentaloma and available final diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using commercially available software package SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA). A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the SUVmax of benign and malignant thyroid incidentalomas. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to identify an SUVmax cutoff in differentiating benign from malignant thyroid incidentalomas.

Results

Incidental focal uptake of tracer in the thyroid was observed in 147 patients. The final diagnosis was achieved in 47/147 (32%) by FNAC in 31 patients, histopathology of the surgical resection specimen in 10 and following neck USG in 6 patients (table 1). In the rest of the patients, final cytological or histopathological diagnosis was not available due to several factors, such as further patient management in other hospitals, advanced primary malignancy with widespread metastatic disease, poor prognosis, low clinical index of suspicion or death. The final diagnosis showed benign lesions in 36 patients, papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) in 5 patients (10.6%), secondary metastases in 3 patients and recurrence of lymphoma in 1 patient (table 1). In 2 patients, FNAC demonstrated indeterminate follicular lesions, but surgical excision was not performed. Thus, 9 out of 47 cases (19.1%) of thyroid focal uptake showed malignant involvement. In 5 patients with PTC, completion thyroidectomy histopathology results were available for 3 patients, which showed pT3N1 disease in 2 patients and pT1aN0 disease in 1 patient.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics with focal uptake in the thyroid where a final diagnosis was available

| No. | Age, years | Sex | Primary | SUVmax | Final diagnosis | Modality for final diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | F | Breast | 7 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 2 | 68 | F | Breast | 3.4 | Benign nodule | USG |

| 3 | 52 | F | Colorectal | 1.7 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 4 | 75 | M | Colorectal | 3.8 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 5 | 72 | F | CUPS | 14.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 6 | 68 | F | CUPS | 2.4 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 7 | 46 | F | Lymphoma (HL) | 1.6 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 8 | 59 | F | Lung | 7.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 9 | 64 | F | Lung | 5.8 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 10 | 84 | M | Lung | 2.9 | Benign nodule | USG |

| 11 | 58 | F | Lung | 5.6 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 12 | 65 | M | Lung | 7.8 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 13 | 73 | F | Lung | 5.9 | Benign nodule | Histopathology |

| 14 | 68 | F | Lung | 5.4 | Benign nodule | Histopathology |

| 15 | 76 | F | Melanoma | 6.7 | Benign nodule | USG |

| 16 | 91 | F | Melanoma | 3.9 | Benign nodule | USG |

| 17 | 46 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 4.9 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 18 | 72 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 2.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 19 | 43 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 3.4 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 20 | 84 | M | Lymphoma (NHL) | 39.0 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 21 | 43 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 4.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 22 | 79 | M | Lymphoma (NHL) | 4.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 23 | 35 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 5.0 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 24 | 82 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 9.9 | Benign nodule | USG |

| 25 | 53 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 2.1 | Benign nodule | Histopathology |

| 26 | 51 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 10.3 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 27 | 71 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 2.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 28 | 66 | M | Lymphoma (NHL) | 5 | Benign nodule | Histopathology |

| 29 | 61 | M | Oesophagus | 9.1 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 30 | 48 | F | Oesophagus | 20.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 31 | 81 | F | SqCC (anterior abdominal wall) | 15 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 32 | 58 | M | SqCC HN | 15 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 33 | 77 | F | Small fibre neuropathy | 5.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 34 | 75 | F | Stomach | 4.5 | Benign nodule | USG |

| 35 | 47 | M | Thymus | 4.5 | Benign nodule | FNAC |

| 36 | 81 | M | Colorectal | 15 | Metastases | Histopathology |

| 37 | 65 | M | SqCC HN | 9.2 | Metastases | FNAC |

| 38 | 65 | F | Lung | 10.7 | Metastases | FNAC |

| 39 | 84 | M | Lymphoma (NHL), lung | 11.5 | NHL | FNAC |

| 40 | 66 | F | Lung | 15.2 | PTC | Histopathology |

| 41 | 58 | M | SPN characterisation | 17.4 | PTC | Histopathology |

| 42 | 46 | M | Lymphoma – Sézary syndome | 15.2 | PTC | Histopathology |

| 43 | 48 | F | Lymphoma (NHL) | 29.4 | PTC | Histopathology |

| 44 | 49 | F | SqCC HN | 17.8 | PTC | Histopathology |

| 45 | 65 | F | Lung | 3.8 | THY3 | FNAC |

| 46 | 49 | M | Thymoma | 8.3 | THY3 | FNAC |

| 47 | 37 | F | Melanoma | 2.1 | Thyroiditis | FNAC |

CUPS = Carcinoma of unknown primary site; NHL = non-Hodgkins lymphoma; HL = Hodgkins lymphoma; SqCC = squamous cell carcinoma; HN = head and neck; SPN = solitary pulmonary nodule; THY3 = follicular lesion/follicular neoplasm.

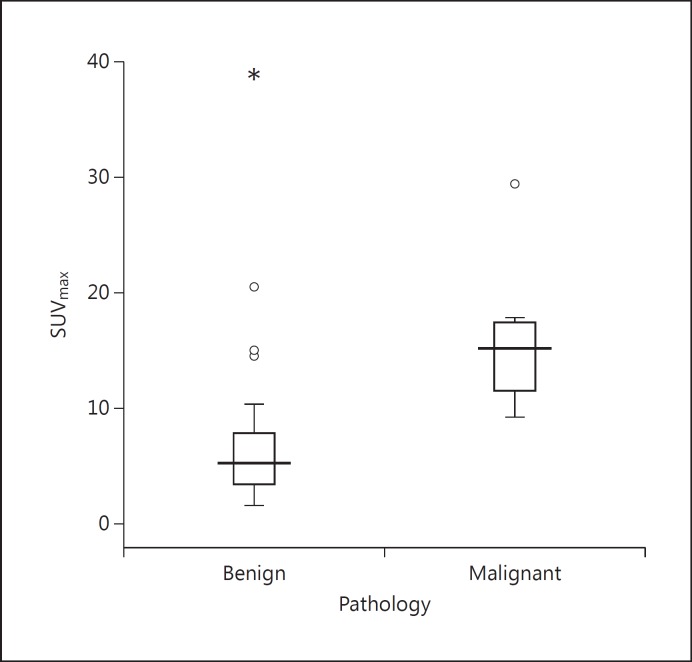

The mean SUVmax of malignant focal thyroid uptake was 15.7 ± 5.9 and that of benign lesions was 7.1 ± 6.8. There was a highly significant difference between the SUVmax in two groups (p = 0.000123; fig. 1). All patients with malignant thyroid pathology had a high SUVmax of the focal uptake. Although most of the benign lesions showed low-grade tracer uptake, a high SUVmax up to 39.0 was observed.

Fig. 1.

Box plots of the SUVmax of benign and malignant focal incidentalomas.

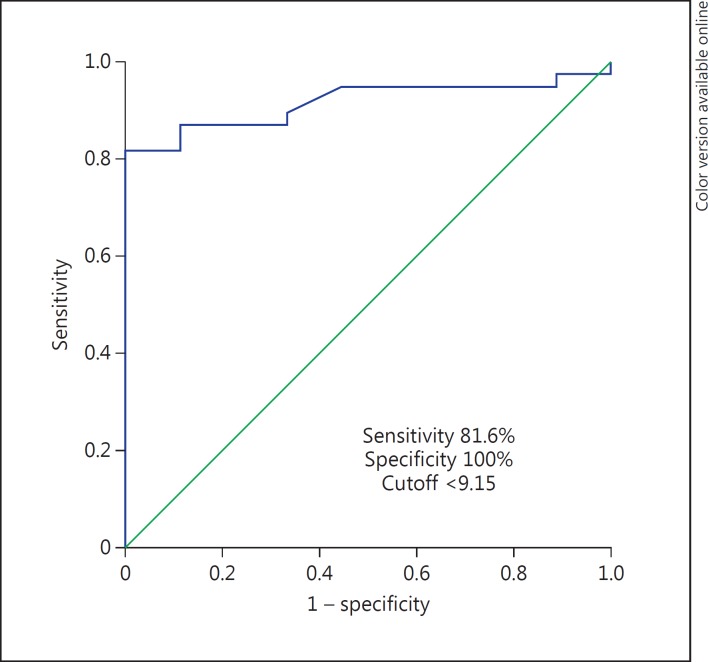

ROC analysis was performed to identify the cutoff SUVmax for differentiating benign from malignant thyroid incidentalomas (fig. 2). The cutoff SUVmax identified was 9.1 (sensitivity: 81.6%, specificity: 100%, area under the curve: 0.915). Further, serial 18F-FDG PET studies were performed in 9 out of 47 patients, which showed a stable SUVmax over 2-12 months in 5 patients with benign pathology. Two patients had new focal uptake in the thyroid when compared to the previous study, which was confirmed as lymphoma recurrence in one and a benign lesion in the other patient. Other two benign incidentalomas showed a variable trend in the SUVmax. Figures 3, 4, 5 demonstrate focal thyroid uptake and its significance in a few cases from the study.

Fig. 2.

ROC analysis to identify the cutoff SUVmax to differentiate benign from malignant incidentalomas.

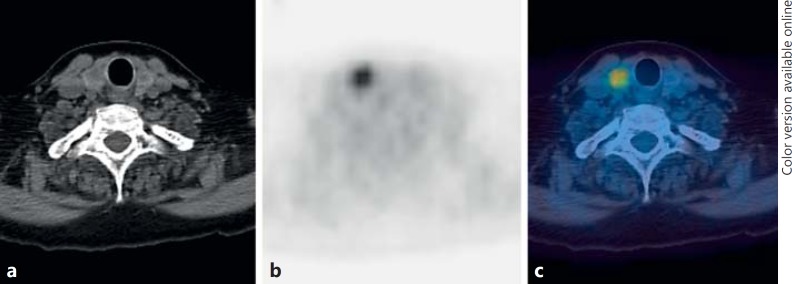

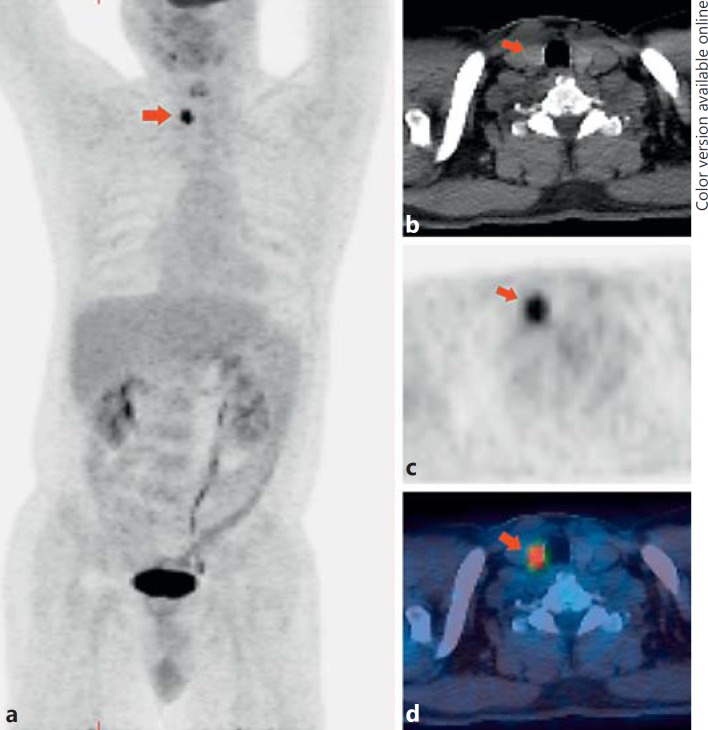

Fig. 3.

A 91-year-old-female with previous history of melanoma on 18F-FDG PET/CT study [axial CT (a), axial PET (b) and fused PET/CT (c)] showed incidental focal uptake in the right thyroid lobe with an SUVmax of 3.9. On USG evaluation the features of right thyroid lobe nodule were suggestive of benign pathology.

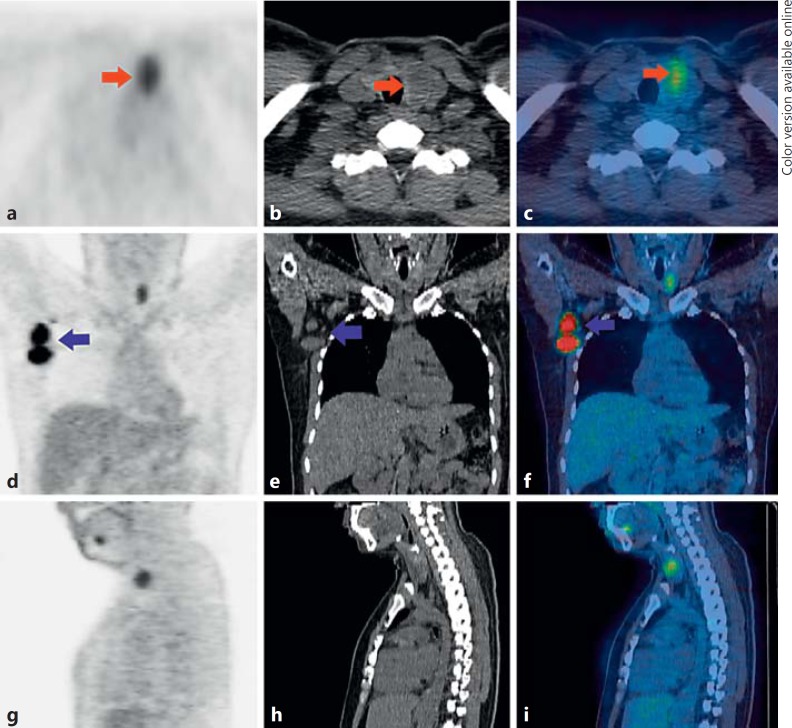

Fig. 4.

A 35-year-old-female with high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma on 18F-FDG PET/CT study [axial PET, CT and fused PET/CT (a-c); coronal PET, CT and fused PET/CT (d–f); sagittal PET, CT and fused PET/CT(g-i)] showed incidental focal uptake in a hypodense nodule in the left thyroid lobe (red arrows; colours refer to the online version only) with an SUVmax of 5.0. In addition, intense uptake was noted in the right axillary lymph nodes (purple arrows; colours refer to the online version only). On histopathology, the left thyroid nodule was confirmed as a benign follicular adenoma.

Fig. 5.

A 58-year-old-male underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT study for assessment of a solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN). 18F-FDG PET/CT showed no uptake in the SPN, but there was intense focal uptake of tracer in a right thyroid lobe nodule [arrow in maximum intensity projection (a), axial CT (b), axial PET (c) and axial fused PET/CT images (d)] with an SUVmax of 17.4. On histopathology it was confirmed as a PTC.

Discussion

18F-FDG is a glucose analogue and its mechanism of uptake is based on the higher glycolytic metabolism and the high expression of GLUT proteins in the malignant tissue [2]. The significance of incidental focal thyroid uptake on 18F-FDG PET study was first described in 2001 [10]. Many research studies are currently available on this topic, with different results on focal uptake of tracer on 18F-FDG PET [3,4,5,6,8,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]; however, a large UK series has yet to be reported. We report one of the largest studies on the evaluation of incidental focal 18F-FDG uptake in the thyroid. The largest study by Bertagna et al. [4] included 49,519 patients, and focal thyroid uptake was identified in 1.5% of the patients. The authors reported that 34.1% of incidentalomas were malignant. Two studies with a large patient population by King et al. [26] and Kwak et al. [30] showed very low prevalence of focal incidentalomas in 0.2 and 0.6% of the patients, respectively, similar to our study. However, the prevalence of thyroid incidentalomas on 18F-FDG PET varies from 0.2 to 10.1% in different studies [4]. This could well be related to variation in geographic area, number of patients studied and patient characteristics.

The incidence of malignant neoplasm in our cohort was19.1% where a final diagnosis was available. Systematic review of previous studies on this topic by Soelberg et al. [39] showed malignancy in 34.8% of patients with focal uptake in the thyroid. However, our study showed a slightly lower incidence of malignant involvement of the thyroid in this population, similar to the King et al. [26] publication.

Previous studies have indicated that PTC and the follicular variant of PTC are the most prevalent thyroid cancer types, accounting for 81.1%, whereas lymphoma and secondary metastatic disease have been seen in only 4.1% of the patients [39]. Our study data is in concordance with previous findings showing PTC as the most frequent histopathological type of primary thyroid cancer in these patients. Further, we did not find any other histopathological subtypes of the thyroid cancer. It has been mentioned previously that malignancy identified within the thyroid on 18F-FDG PET may be more aggressive, which could be due to the fact that 18F-FDG PET has less sensitivity in identifying differentiated cancers [5]. Interestingly, our results demonstrated that all incidentalomas with primary thyroid malignancies had differentiated PTC, with 1 patient having pT1a disease. FDG avid lesions are likely to be those that express GLUT1 intensely. There is some evidence that phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN)-negative PTC have considerable GLUT1 expression, and the relationship between the increasingly understood genetic alterations (BRAF, PTEN, etc.) and FDG avidity merits further study [40]. Furthermore, contradicting the previous findings, we found that almost half (44.4%) of the patients with malignant incidentaloma were due to secondary metastases or lymphoma.

The SUV assessed by 18F-FDG PET/CT is a semi-quantitative measure of glucose metabolism, which often reflects metabolic activity frequently correlated with biologic aggressiveness and clinical behaviour of malignant lesions, though not specific for malignancy. Literature evidenceon the SUVmax in benign and malignant lesions vary with several reports showing a statistically significant difference [9,13,19,21,22,23,34,41] whilst many others have shown no significant difference [8,14,15,27,30,32,33,35,36]. Previous studies have also reported cutoff SUV values ranging from 3.5 to 5 in differentiated benign to malignant thyroid lesions [24,34,41]. In our study, a highly statistical difference was present between the SUVmax of benign and malignant lesions. We found a cutoff value of 9.1 had 81.6% sensitivity and 100% specificity in differentiating benign from malignant lesions.

Considering the literature evidence and following the findings from our study, it may be suggested that in patients with an incidental focal thyroid uptake, an SUVmax <3.3 and low clinical risk, one may be able to reassure the patients [42]. However, if there is a high clinical risk (such as previous history of radiation exposure and family history of thyroid cancer) or if the SUVmax is higher, the thyroid uptake should be regarded as suspicious for underlying malignancy and investigated further as appropriate. However, in patients with widespread metastases with poor prognosis, further investigation of incidental thyroid uptake may not be appropriate. The decision regarding investigating the incidental thyroid uptake needs to be made on an individual patient basis.

There are some limitations to our study which need to be mentioned. This being a retrospective study, a definitive diagnosis could not be available in many patients due to reasons such as further patient management in other hospitals, advanced primary malignancy with widespread metastatic disease, poor prognosis, low clinical index of suspicion or death. As data was collected over nearly 14 years, the studies were performed on different PET or PET/CT scanners. To our knowledge, however, this is the largest UK series on thyroid incidentalomas over the past 14 years. The results of this study are important as a lot of these findings were determined in a cohort of patients with poor prognosis or who may be terminally ill. It is also essential that patients with incidental focal thyroid uptake are properly evaluated and a collaborative protocol is established between referring clinicians, nuclear medicine physicians, endocrinologists and thyroid surgeons for the appropriate management of these patients.

Conclusion

Incidence of focal thyroid uptake on 18F-FDG PET study remains rare in our study cohort. The malignancy potential of these lesions, however, remains high and warrants prompt follow-up by the clinician. The SUVmax may aid in further characterisation of the lesion and its management. Incidence of malignant primary and secondary pathology within these lesions remains equally possible.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dean DS, Gharib H. Epidemiology of thyroid nodules. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahl RL. Targeting glucose transporters for tumor imaging: ‘sweet’ idea, ‘sour’ result. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1038–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yiyan Liu. Clinical significance of thyroid uptake on F18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s12149-008-0198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertagna F, Treglia G, Piccardo A, Giovannini E, Bosio G, Biasiotto G, Bahij el K, Maroldi R, Giubbini R. F18-FDG PET/CT thyroid incidentalomas: a wide retrospective analysis in three Italian centres on the significance of focal uptake and SUV value. Endocrine. 2013;43:678–685. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9837-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Are C, Hsu JF, Ghossein RA, Schoder H, Shah JP, Shaha AR. Histological aggressiveness of fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomogram (FDG-PET)-detected incidental thyroid carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3210–3215. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9531-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prichard RS, Cotter M, Evoy D, Gibbons D, Collins C, McDermott E, Skehan S. Focal thyroid incidentalomas identified with whole-body FDG-PET warrant further investigation. Ir Med J. 2011;104:177–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visser EP, Boerman OC, Oyen WJ. SUV: from silly useless value to smart uptake value. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:173–175. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Are C, Hsu JF, Schoder H, Shah JP, Larson SM, Shaha AR. FDG-PET detected thyroid incidentalomas: need for further investigation? Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:239–247. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9181-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen MS, Arslan N, Dehdashti F, Doherty GM, Lairmore TC, Brunt LM, Moley JF. Risk of malignancy in thyroid incidentalomas identified by fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography. Surgery. 2001;130:941–946. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.118265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramos CD, Chisin R, Yeung HW, Larson SM, Macapinlac HA. Incidental focal thyroid uptake on FDG positron emission tomographic scans may represent a second primary tumor. Clin Nucl Med. 2001;26:193–197. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salvatori M, Melis L, Castaldi P, Maussier ML, Rufini V, Perotti G, Rubello D. Clinical significance of focal and diffuse thyroid diseases identified by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61:488–493. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YK, Ding HJ, Chen KT, Chen YL, Liao AC, Shen YY, Su CT, Kao CH. Prevalence and risk of cancer of focal thyroid incidentaloma identified by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for cancer screening in healthy subjects. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1421–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi JY, Lee KS, Kim HJ, Shim YM, Kwon OJ, Park K, Baek CH, Chung JH, Lee K, Kim BT. Focal thyroid lesions incidentally identified by integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT: clinical significance and improved characterization. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:609–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TY, Kim WB, Ryu JS, Gong G, Hong SJ, Shong YK. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in thyroid from positron emission tomogram (PET) for evaluation in cancer patients: high prevalence of malignancy in thyroid PET incidentaloma. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1074–1078. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000163098.01398.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogsrud TV, Karantanis D, Nathan MA, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Collins DA, Kasperbauer JL, Strome SE, Reading CC, Hay ID, Lowe VJ. The value of quantifying 18F-FDG uptake in thyroid nodules found incidentally on whole-body PET-CT. Nucl Med Commun. 2007;28:373–381. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3280964eae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu QD, Connor MS, Lilien DL, Johnson LW, Turnage RH, Li BD. Positron emission tomography (PET) positive thyroid incidentaloma: the risk of malignancy observed in a tertiary referral center. Am Surg. 2006;72:272–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimori H, Tabah R, Hickeson M, How J. Incidental thyroid ‘PETomas’: clinical significance and novel description of the self-resolving variant of focal FDG-PET thyroid uptake. Can J Surg. 2011;54:83–88. doi: 10.1503/cjs.023209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishimori T, Patel PV, Wahl RL. Detection of unexpected additional primary malignancies with PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:752–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang KW, Kim SK, Kang HS, Lee ES, Sim JS, Lee IG, Jeong SY, Kim SW. Prevalence and risk of cancer of focal thyroid incidentaloma identified by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for metastasis evaluation and cancer screening in healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4100–4104. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilsson IL, Arnberg F, Zedenius J, Sundin A. Thyroid incidentaloma detected by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography: practical management algorithm. World J Surg. 2011;35:2691–2697. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho TY, Liou MJ, Lin KJ, Yen TC. Prevalence and significance of thyroid uptake detected by 18F-FDG PET. Endocrine. 2011;40:297–302. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim BH, Na MA, Kim IJ, Kim SJ, Kim YK. Risk stratification and prediction of cancer of focal thyroid fluorodeoxyglucose uptake during cancer evaluation. Ann Nucl Med. 2010;24:721–728. doi: 10.1007/s12149-010-0414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagano L, Sama MT, Morani F, Prodam F, Rudoni M, Boldorini R, Valente G, Marzullo P, Baldelli R, Appetecchia M, Isidoro C, Aimaretti G. Thyroid incidentaloma identified by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with CT (FDG-PET/CT): clinical and pathological relevance. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75:528–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bae JS, Chae BJ, Park WC, Kim JS, Kim SH, Jung SS, Song BJ. Incidental thyroid lesions detected by FDG-PET/CT: prevalence and risk of thyroid cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhai G, Zhang M, Xu H, Zhu C, Li B. The role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography whole body imaging in the evaluation of focal thyroid incidentaloma. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33:151–155. doi: 10.1007/BF03346574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King DL, Stack BC, Jr, Spring PM, Walker R, Bodenner DL. Incidence of thyroid carcinoma in fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-positive thyroid incidentalomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:400–404. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nam SY, Roh JL, Kim JS, Lee JH, Choi SH, Kim SY. Focal uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose by thyroid in patients with nonthyroidal head and neck cancers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:135–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Even-Sapir E, Lerman H, Gutman M, Lievshitz G, Zuriel L, Polliack A, Inbar M, Metser U. The presentation of malignant tumours and pre-malignant lesions incidentally found on PET-CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:541–552. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-0056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohba K, Nishizawa S, Matsushita A, Inubushi M, Nagayama K, Iwaki H, Matsunaga H, Suzuki S, Sasaki S, Oki Y, Okada H, Nakamura H. High incidence of thyroid cancer in focal thyroid incidentaloma detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose [corrected] positron emission tomography in relatively young healthy subjects: results of 3-year follow-up. Endocr J. 2010;57:395–401. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwak JY, Kim EK, Yun M, Cho A, Kim MJ, Son EJ, Oh KK. Thyroid incidentalomas identified by 18F-FDG PET: sonographic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:598–603. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh H, Lin S, Yang B, Chu Y, Chang C, Liu R. The clinical relevance of thyroid incidentalomas detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Ann Nucl Med Sci. 2003;16:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen W, Parsons M, Torigian DA, Zhuang H, Alavi A. Evaluation of thyroid FDG uptake incidentally identified on FDG-PET/CT imaging. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30:240–244. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328324b431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eloy JA, Brett EM, Fatterpekar GM, Kostakoglu L, Som PM, Desai SC, Genden EM. The significance and management of incidental [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose-positron-emission tomography uptake in the thyroid gland in patients with cancer. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1431–1434. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang BJ, Hyun J, Baik JH, Jung SL, Park YH, Chung SK. Incidental thyroid uptake on F-18 FDG PET/CT: correlation with ultrasound and pathology. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23:729–737. doi: 10.1007/s12149-009-0299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonabi S, Schmidt F, Broglie MA, Haile SR, Stoeckli SJ. Thyroid incidentalomas in FDG-PET/CT: prevalence and clinical impact. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:2555–2560. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-1941-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pampaloni MH, Win AZ. Prevalence and characteristics of incidentalomas discovered by whole body FDG PETCT. Int J Mol Imaging. 2012;2012:476763. doi: 10.1155/2012/476763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee WM, Kim BJ, Kim MH, Choi SC, Ryu SY, Lim I, Kim K. Characteristics of thyroid incidentalomas detected by pre-treatment [F]FDG PET or PET/CT in patients with cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2012;23:43–47. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2012.23.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim H, Kim SJ, Kim IJ, Kim K. Thyroid incidentalomas on FDG PET/CT in patients with non-thyroid cancer – a large retrospective monocentric study. Onkologie. 2013;36:260–264. doi: 10.1159/000350305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soelberg KK, Bonnema SJ, Brix TH, Hegedüs L. Risk of malignancy in thyroid incidentalomas detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: a systematic review. Thyroid. 2012;22:918–925. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morani F, Pagano L, Prodam F, Aimaretti G, Isidoro C. Loss of expression of the oncosuppressor PTEN in thyroid incidentalomas associates with GLUT1 plasma membrane expression. Panminerva Med. 2012;54:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boeckmann J, Bartel T, Siegel E, Bodenner D, Stack BC., Jr Can the pathology of a thyroid nodule be determined by positron emission tomography uptake? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:906–912. doi: 10.1177/0194599811435770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qu N, Zhang L, Lu ZW, Wei WJ, Zhang Y, Ji QH. Risk of malignancy in focal thyroid lesions identified by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography: evidence from a large series of studies. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:6139–6147. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1813-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]