Abstract

Background

Since the identification of the first case of infection with the Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus (MERS-CoV) in Saudi Arabia in June 2012, the number of laboratory-confirmed cases has exceeded 941 cases globally, of which 347 died. The disease presents as severe respiratory infection often with shock, acute kidney injury, and coagulopathy. Recently, we observed three cases who presented with neurologic symptoms. These are so far the first reported cases of neurologic injury associated with MERS-CoV infection.

Methods

Data was retrospectively collected from three patients admitted with MERS-CoV infection to Intensive Care unit (ICU) at King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh. They were managed separately in three different wards prior to their admission to ICU.

Finding

The three patients presented with severe neurologic syndrome which included altered level of consciousness ranging from confusion to coma, ataxia, and focal motor deficit. Brain MRI revealed striking changes characterized by widespread, bilateral hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted imaging within the white matter and subcortical areas of the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, the basal ganglia, and corpus callosum. None of the lesions showed gadolinium enhancement.

Interpretation

CNS involvement should be considered in patients with MERS-CoV and progressive neurological disease, and further elucidation of the pathophysiology of this virus is needed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0720-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus, Encephalitis, Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, Stroke, Pneumonia, Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Introduction

Since the identification of the first case of infection with the Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus (MERS-CoV) in Saudi Arabia in June 2012 [1], the number of laboratory-confirmed cases has exceeded 941 cases globally, of which 347 died [2]. The disease presents as severe respiratory infection often with shock, acute kidney injury, and coagulopathy [3]. We recently have reported the clinical manifestations and outcome in 12 patients with MERS-CoV infection admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) [4]. Here we report three cases presenting with severe neurologic syndrome. To our knowledge, these are the first identified cases of neurologic injury associated with MERS-CoV infection.

Methods

Setting

Three patients from King Abdulaziz Medical City in Riyadh presented from the community in February and March 2014. They were admitted to different wards and were managed separately prior to admission to the ICU. There was no hospital transmission of MERS-CoV among healthcare workers during their hospitalization. Approval to collect data for these patients and report them was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Ministry of National Guard-Health Affairs. The consent was waived because of the observational nature of the study as per the institutional policy.

Patients

The clinical course as well as the laboratory and radiological findings of three patients with community-acquired MERS-CoV and progressive neurological findings were assessed by reviewing medical records and interviewing the managing team. Testing for MERS-CoV was performed by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as described in the online supplement.

Patient 1

A 74-year-old Saudi male patient with diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia presented with a 3 days of ataxia, vomiting, confusion, and fever of 39.5 °C (Fig. 1). Examination revealed dysmetria and decreased motor power on the left side. Chest radiograph showed infiltrate in the mid right lung zone. Computerized tomography (CT scan) of the brain showed multiple chronic lacunar strokes but no acute changes. He was admitted to the ward with a working diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia and possible stroke and was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, and required no intensive care at that time. Because of his neurologic symptoms, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on hospital day (HD) 5 was obtained and showed moderate chronic small vessel ischemic changes (Fig. 2).

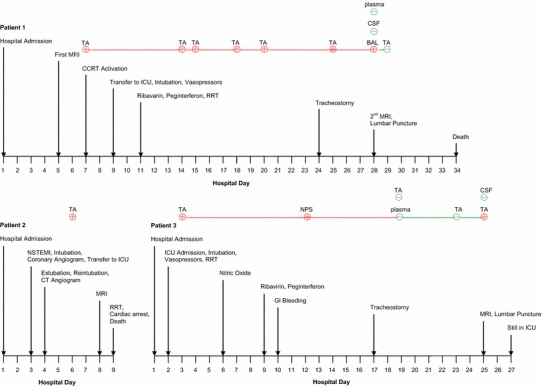

Fig. 1.

Timeline of pertinent events and MERS-CoV RT-PCR results in patients 1, 2, and 3. MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, CCRT critical care response team, ICU intensive care unit, RRT renal replacement therapy, TA tracheal aspirate, BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, NSTEMI non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, GI gastrointestinal

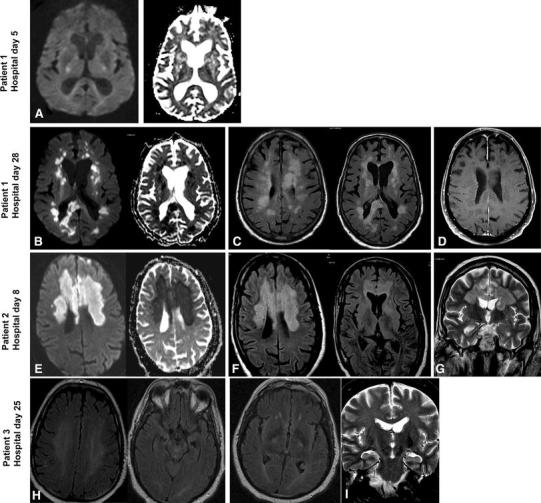

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the three patients. Patient 1—First MRI—day 5: a Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) mapping showed patchy non-specific signal changes with no restriction. Further images were not obtained because patient could not tolerate the test. Patient 1—Second MRI—day 28: b Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) mapping showed diffusion restriction of the multiple white matter lesions. c Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images showed multiple hyperintense lesions in the subcortical areas and deep white matter of frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes bilaterally as well as in the corpus callosum. d Axial contrast enhanced T1-weighted (T1Wl) showed multiple subcortical areas and deep white matter non-enhancing lesions. Patient 2—Day 8: e DWI and ADC mapping showed diffusion restriction of the bilateral frontal and corpus callosum lesions. f Axial FLAIR images showed bilateral confluent subcortical areas and deep white matter hyperintense lesions in the frontal lobes, basal ganglia, and corpus callosum. g Coronal T2 images showed bilateral hyperintense white matter lesions in the frontal lobes and in the corpus callosum. Patient 3—Day 25: h Axial FLAIR Images showing diffuse white matter (deep) signal abnormality at the insular region bilaterally. i Coronal T2-weighted images showing abnormality involving corticospinal tract bilaterally extending to the brain stem

On HD 7, he was referred to the critical care response team because of increasing dyspnea and hypoxia, persistent fever, and progression in air space disease on chest radiographs (Online Figure 1) and was started on oseltamivir, bronchodilators, and methylprednisolone. MERS-CoV RT-PCR was sent from tracheal aspirate according to guidelines for management of critically ill patients with lower repertory illness and returned positive. Further history revealed exposure to camels. On HD 9, he was transferred to the ICU, where he was awake but severely hypoxic with oxygen saturation of 68–75 % on 100 % oxygen via non-rebreather mask. During his ICU stay, patient was managed as a case of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which required intubation and mechanical ventilation by lung protective strategy, intravenous sedation, neuromuscular blockers, prone positioning, and inhaled nitric oxide. He required vasopressors and continuous renal replacement therapy. On HD 11, he was given peginterferon alpha-2b and ribavirin [5]. Subsequent MERS-CoV tests were positive until HD 28 (Fig. 1).

On HD 24, his respiratory status improved and tracheostomy was performed. However, he remained comatose with Glasgow Coma Scale of 3–4; and a repeat CT scan of the brain showed an interval development of numerous patchy hypodensities in the periventricular deep white matter and subcortical region, bilateral basal ganglia, thalami, pons, cerebellum, and cerebellar pedicles in addition to a large hypodensity in the splenium and posterior body of the corpus callosum. MRI identified multiple bilateral patchy areas of signal abnormality that appeared high on T2/FLAIR images seen in the periventricular, deep white matter, subcortical area, corpus callosum, bilateral brachium pontis, midbrain as well as in the left cerebellum and upper cervical cord. The lesions were non-enhancing and showed diffusion restriction (Fig. 2).

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a white cell count of 1 cell and protein of 0.56 g/L (reference 0.15–0.40 g/L) and negative MERS-CoV RT-PCR. The patient had lymphopenia throughout his illness (Online Figure 2). Lymphocyte subset analysis revealed critically low absolute CD4 and CD8 count with a normal ratio (Table 1). Other tests are available online. Due to deep coma, poor overall condition and worsening cardiovascular and respiratory status, he expired on HD 34.

Table 1.

Lymphocyte subset analysis in patients 1 and 3

| Patient 1 | Patient 3 | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White cell count | |||

| ×109/L | 4.3 | 4.10 | 4.0–11.0 |

| Lymphocytes | |||

| % | 3 | 12 | 20–45 |

| CD3+[T cell] | |||

| cells/μL | 16 | 399 | 1100–1700 |

| % | 58 | 81 | 67–76 |

| CD3+CD4+(T helper) | |||

| cells/μL | 12 | 166 | 700–1100 |

| % | 46 | 33 | 38–40 |

| CD3+CD8 (T suppressor) | |||

| cells/μL | 4 | 210 | 500–900 |

| % | 13 | 42 | 31–40 |

| CD19+(B cells) | |||

| cells/μL | 9 | 58 | 200–400 |

| % | 33 | 12 | 11–16 |

| CD16+CD56+(NK) | |||

| cells/μL | 1.0 | 26 | 200–400 |

| % | 5 | 5 | 10–19 |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 3.54 | 0.79 | 1–1.5 |

Patient 2

A 57-year-old diabetic, hypertensive, Saudi male with peripheral vascular disease presented with 3 days of flu-like illness, fever (39.0 °C), and a gangrenous toe. His working diagnosis was diabetic foot and was empirically started on broad-spectrum antibiotics. On HD 2 he developed acute myocardial ischemia with pulmonary edema (Online Figure 1) for which he was intubated. An emergency coronary angiography revealed chronic severe 3-vessel disease with no acute vessel closure (Fig. 1). Troponin level peaked to 13.5 ng/mL at 12 h and his electrocardiogram returned to normal within 48 h consistent with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). He was extubated on HD 4 but 2 h later he became unresponsive, hypotensive with left-sided facial paralysis, and required reintubation. Brain CT scan showed two subtle hypodensities seen at the right semiovale and left basal ganglia likely representing small lacunar infarctions. CT angiography showed near total occlusion at the origin of both internal carotid arteries with intracranial narrowing of the left middle cerebral artery at M1 segment and intact anterior communicating artery, and bilateral anterior cerebral arteries (ACA) with no radiographic features of vasculitis. (Online Figure 3). On HD 6, he had recurrence of fever with leukopenia (WBC 3.2 × 109) and a respiratory sample for MERS-CoV tested positive. On HD 8, repeat brain CT scan showed interval multiple patchy hypodensities bilaterally in the periventricular, deep white matter and bilateral basal ganglia, and a large area of hypodensity in the proximal half of the corpus callosum up to the mid part of his body. MRI showed signal abnormality bilaterally in the deep watershed and in the parasagittal region as well as scattered foci in the cortical and subcortical regions of the temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes with restriction on the diffusion weighted images (DWI) consistent with acute infarction (Fig. 2). On HD 9, his condition progressed to severe shock and acute kidney injury, had multiple cardiac arrests and expired. No CSF samples were taken on this patient.

Patient 3

A 45-year-old diabetic, hypertensive Saudi male with chronic kidney disease and ischemic heart disease presented with a 10-day history of productive cough, dyspnea, rigors, fever, and diarrhea with no significant travel or animal exposure. He was conscious and had no focal neurological findings. Chest radiograph showed an infiltrate in the lower and mid right zones. He was admitted with a working diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia and acute kidney injury. He was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, oseltamivir, and renal replacement therapy. On HD 2, he required intubation and ICU admission for severe ARDS, which was managed by a lung protective strategy, intravenous sedation, neuromuscular blockers, and nitric oxide. He required vasopressors and continuous renal replacement therapy. His tracheal aspirate tested positive for MERS-CoV and no other pathogens were detected. On HD 9, he was given peginterferon alpha-2b and ribavirin [5]. Subsequent MERS-CoV tests from respiratory samples were positive (Fig. 1). He recovered from septic shock and respiratory failure, and had tracheostomy placed on HD 24. Because of low Glasgow Coma Scale and fever, brain CT scan was performed and showed no acute abnormality. MRI showed confluent T2WI/FLAIR hyperintensity within the white matter of both cerebral hemispheres and along the corticospinal tract. There was no diffusion restriction or abnormal enhancement after administration of contrast. These findings were considered to be consistent with encephalitis. CSF analysis showed a white cell count of 2 cells, and protein of 0.85 g/L with negative MERS-CoV RT-PCR. Other tests are listed in the online supplement. Lymphocyte counts were low (Online Figure 2) and lymphocyte subsets were markedly reduced (Table 1). This patient was discharged home on HD 107.

Discussion

Three patients were admitted with 3 different working diagnoses with fever as one of the initial symptoms. Each eventually developed symptoms raising an index of suspicion for MERS-CoV infection, which was confirmed by RT-PCR. In addition, all had neurologic symptoms: at presentation for patient 1 and on HD 5 and 24 for patients 2 and 3, respectively. The neurologic manifestations included altered mental level ranging from confusion to coma, ataxia, and focal motor deficits. Given the significant comorbidities and the severe critical illness, such neurological findings may easily be attributed to other common etiologies. However, the striking findings of the MRI from our first patient raised the concern for critically examining the subsequent two patients. Brain MRI revealed new-onset widespread, bilateral hyperintense lesions on T2WI within the white matter and subcortical areas of the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, the basal ganglia and corpus callosum, pons, cerebellum, and upper cervical cord. None enhanced with gadolinium. CSF examination in two patients was unremarkable with the exception of increased protein level. Besides the neurological manifestations, the three patients had several things in common; all had other organ dysfunctions involving respiratory, renal, and cardiovascular systems, all had persistent viral shedding from the respiratory tract, and had lymphopenia with a profound depression of T and B lymphocyte subsets. So the neurologic syndrome in the context of severe MERS-CoV infection and the distinct imaging patterns suggest that MERS-CoV infection may be responsible for the extensive CNS injury observed in our patients.

Although the clinical, radiological, and laboratory findings were suggestive of MERS-CoV associated neurological illness, several differential diagnoses were considered, given the lack of confirmatory test of brain infection namely the presence of corona virus in the brain tissue and/or in the CSF. In addition, the use of sedation as part of the management of severe ARDS may have masked the onset or the progression of neurologic manifestations. Because of the presence of risk factors, acute ischemic stroke was first sought but ruled out by brain imaging, except for patient 2. Other potential explanations to the neurologic findings such as air and fat embolism, or post-anoxic damage were also considered, although less likely. The two patients requiring high ventilator settings did not exhibit any evidence of barotrauma. Fat embolism appears unlikely given the lack of risk factors. None of the patient had sustained cardiovascular arrest. Although one of the patients had severe hypoxemia, it was not associated with neurologic abnormalities and resolved after intubation. Moreover, the MRI findings did not follow the typical changes associated neither with hypoxia–ischemia. Indeed, brain MRI of patient 1 is rather supportive of a viral etiology, more specifically of an acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) [6], an immune mediated disease that often occurs following viral infection [7]. It is also consistent with encephalitis, albeit less probably due to the predominant white matter involvement and the striking restricted diffusion. In patient two, the MRI findings were suggestive of bilateral anterior cerebral artery stroke. It is known that patients with cardiovascular risk factors are at high risk of developing a cerebral stroke during sepsis or during their hospitalization in an ICU, independently to the etiology of the sepsis or the cause of admission to an ICU. However, in our case the CT angiogram performed after the onset of neurologic deficits showed patent ACAs. Stroke caused by viral vasculopathy has been described with other viruses including varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and human immunodeficiency virus [8]. Therefore, it is conceivable that the observed non-occlusive stroke and myocardial infraction are associated with MERS-CoV vasculopathy.

MERS-CoV is one of the human corona viruses that include also five other strains: SARS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL-63, and HCoV-HKU1. Although corona viruses are generally known for causing respiratory illness, both clinical and experimental studies have demonstrated their strong tropism to the CNS [9–15]. SARS-CoV infection induced in mice model results in neuronal death without encephalitis [16]. Brain necropsy study in eight confirmed cases of SARS revealed direct viral infection of neuronal cells located in the cortex and hypothalamus [17] with edema and scattered red degeneration suggesting neuronal ischemia type of injury. Laboratory studies have shown that HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-229E also have the ability to infect human neural cells including neurons and glial cells [12, 13, 18–20]. In addition, HCoV-OC43 has been detected in the CSF of a child with ADEM. Direct evidence that MERS-CoV is the cause of CNS damage observed in our patients is difficult to ascertain due to the lack of brain pathology samples. Our patients were severely ill, and no effective therapy exists to justify further invasive diagnostic approach. The negative CSF for MERS-CoV RT-PCR may be due to the timing of the test, the lack of meningeal involvement as shown on MRI or that the virus is intra-neuronal as reported with SARS-CoV [21].

To the best of our knowledge, no neurologic involvement with MERS-CoV has been so far reported. Hence, our cases raise important questions. What are the pathogenic mechanisms that underlie the occurrence of neurologic injury in our patients? In other words, is it related to specific host factors in these patients or related to a newly acquired virulence leading to neurotropism of the MERS-CoV? [9, 13] One interesting question raised from these cases is whether there is a link between the observed lymphopenia and the observed neurologic manifestations. The receptor for MERS-CoV was recently identified as dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4, also known as CD26) [22]. DPP4 is expressed on T-cells and in the lung, kidney, placenta, liver, skeletal muscle, heart, brain, endothelium, and pancreas [23]. The presence of these receptors may be linked to their susceptibility of these organs, including the brain, to infection [24] but this needs further study.

Conclusion

MERS-CoV infection causes multiple organ damage including pulmonary, cardiovascular, renal, coagulation, gastrointestinal tract, and muscles. Our observation suggests that CNS may be another target of MERS-CoV infection, and thus should be considered in any patients with progressive or worsening CNS findings.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Data access and responsibility

Dr. Yaseen Arabi (PI) had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity and the accuracy of the data.

Contributor Information

Y. M. Arabi, Phone: +966-11-8011111, Email: yaseenarabi@yahoo.com, Email: icu1@ngha.med.sa

A. Harthi, Email: HarthiA@ngha.med.sa

J. Hussein, Email: jawadH@ngha.med.sa

A. Bouchama, Email: BouchamaAb@ngha.med.sa

S. Johani, Email: JohaniS@ngha.med.sa

A. H. Hajeer, Email: Hajeera@ngha.med.sa

B. T. Saeed, Email: saeedba@ngha.med.sa

A. Wahbi, Email: WahbiA@ngha.med.sa

A. Saedy, Email: SaedyAb@ngha.med.sa

T. AlDabbagh, Email: DabbaghT@ngha.med.sa

R. Okaili, Email: OkailiR@ngha.med.sa

M. Sadat, Email: sadatmu@ngha.med.sa

H. Balkhy, Email: balkhyh@ngha.med.sa

References

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—update. http://www.who.int/csr/don/26-december-2014-mers/en/. Accessed 15 Jan 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.The Who Mers-Cov Research G. State of knowledge and data gaps of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in humans. PLoS Curr. 2013; 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Arabi YM, Arifi AA, Balkhy HH, Najm H, Aldawood AS, Ghabashi A, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann Intern Med. 2014;60:389–397. doi: 10.7326/M13-2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Momattin H, Mohammed K, Zumla A, Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA. Therapeutic options for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—possible lessons from a systematic review of SARS-CoV therapy. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e792–e798. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin SE, Callen DJ. The magnetic resonance imaging appearance of monophasic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: an update post application of the 2007 consensus criteria. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2013;23:245–266. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elhassanien AF, Aziz HA. Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis: clinical characteristics and outcome. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2013;8:26–30. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.111418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagel MA, Mahalingam R, Cohrs RJ, Gilden D. Virus vasculopathy and stroke: an under-recognized cause and treatment target. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2010;10:105–111. doi: 10.2174/187152610790963537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Brison E, Meessen-Pinard M, Talbot PJ. Neuroinvasive and neurotropic human respiratory coronaviruses: potential neurovirulent agents in humans. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;807:75–96. doi: 10.1007/978-81-322-1777-0_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau KK, Yu WC, Chu CM, Lau ST, Sheng B, Yuen KY. Possible central nervous system infection by SARS coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:342–344. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergmann CC, Lane TE, Stohlman SA. Coronavirus infection of the central nervous system: host-virus stand-off. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh EA, Collins A, Cohen ME, Duffner PK, Faden H. Detection of coronavirus in the central nervous system of a child with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e73–e76. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbour N, Day R, Newcombe J, Talbot PJ. Neuroinvasion by human respiratory coronaviruses. J Virol. 2000;74:8913–8921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.19.8913-8921.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita M, Yamate M, Li GM, Ikuta K. Susceptibility of human and rat neural cell lines to infection by SARS-coronavirus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Zhong S, Liu J, Li L, Li Y, Wu X, et al. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the brain: potential role of the chemokine mig in pathogenesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1089–1096. doi: 10.1086/444461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, Cassell M, Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol. 2008;82:7264–7275. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00737-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, Zheng J, Gao Z, Zhong Y, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202(3):415–424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonavia A, Arbour N, Yong VW, Talbot PJ. Infection of primary cultures of human neural cells by human coronaviruses 229E and OC43. J Virol. 1997;71:800–806. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.800-806.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arbour N, Cote G, Lachance C, Tardieu M, Cashman NR, Talbot PJ. Acute and persistent infection of human neural cell lines by human coronavirus OC43. J Virol. 1999;73:3338–3350. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3338-3350.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arbour N, Ekande S, Cote G, Lachance C, Chagnon F, Tardieu M, et al. Persistent infection of human oligodendrocytic and neuroglial cell lines by human coronavirus 229E. J Virol. 1999;73:3326–3337. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3326-3337.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu J, Korteweg C. Pathology and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(4):1136–1147. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raj VS, Mou H, Smits SL, Dekkers DH, Muller MA, Dijkman R, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495:251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbott CA, Baker E, Sutherland GR, McCaughan GW. Genomic organization, exact localization, and tissue expression of the human CD26 (dipeptidyl peptidase IV) gene. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:331–338. doi: 10.1007/BF01246674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payne DC, Iblan I, Alqasrawi S, Al Nsour M, Rha B, Tohme RA, et al. Stillbirth during infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(12):1870–1872. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.