Abstract

Background

Nilotinib inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of ABL1/BCR-ABL1, as well as KIT, platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs), and the discoidin domain receptor. Gain-of-function mutations in KIT or PDGFRα are key drivers in most gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs). This trial was designed to test the efficacy and safety of nilotinib vs imatinib as first-line therapy for patients with advanced GISTs.

Methods

This randomised, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial included 647 adult patients with previously untreated, histologically confirmed, metastatic and/or unresectable GISTs. Patients were stratified by prior adjuvant therapy and randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive oral imatinib 400 mg once daily or oral nilotinib 400 mg twice daily. Centrally reviewed progression-free survival (PFS) was the primary endpoint. Response rates, toxicity, and overall survival were also analysed for the overall population and for mutation-defined subsets. Efficacy endpoints used the intention to treat principle. Here, the final results are reported. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00785785.

Findings

Because the futility boundary was crossed at a preplanned interim analysis, trial accrual terminated in April 2011. At final analysis of the core study (data cutoff, October 2012), PFS was higher with imatinib overall (hazard ratio [HR] 1.47) and in the KIT exon 9 subgroup (HR 32.46) but roughly similar between arms in the KIT exon 11 subgroup (HR 1.12). Sensitivity analyses suggested that informative censoring may have contributed, because of the high proportion of premature nilotinib progressions declared by local investigators and the design changes implemented following the interim analysis, potentially biasing PFS data in favour of the nilotinib arm. The most common adverse events were nausea, diarrhoea, and peripheral oedema in the imatinib arm and rash, nausea, and abdominal pain in the nilotinib arm. The most common serious adverse event in both arms was abdominal pain (imatinib, n=11 [3.5%]); nilotinib, n= 14 [4.4%]).

Interpretation

Our results suggest that nilotinib is not an optimal treatment approach for first-line GIST; however, future studies may identify patient subsets form whom first-line nilotinib could be of clinical benefit.

Funding

Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are a family of genotypically distinct malignancies, primarily driven by gain-of-function mutations in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha (PDGFRα).1 Imatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of ABL1/BCR-ABL1, KIT, PDGFRα and -β, the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R), and the discoidin domain receptors (DDR-1 and -2).2 Worldwide, imatinib is the standard first-line therapy for patients with metastatic and/or unresectable GISTs; median progression-free survival (PFS) is 18 to 29 months and a median overall survival (OS) is 55 to 76 months (compared with OS of 9-19 months in the pre-imatinib era).3–9 Although sunitinib and regorafenib are available following failure of imatinib,3–9 disease progression remains a major issue and a cause of death.10

Most GISTs (75%) harbour KIT mutations (exon 11, 65%; exon 9, 8%).1 GISTs with PDGFRα mutations and those without KIT or PDGFRα mutations (misnamed “wild-type” GISTs, generally exhibiting SDH(x), NF1, or BRAF gene mutations) occur less often (10% and 15%, respectively, in series of metastatic GIST).1 KIT exon 11 mutations are associated with the most favourable initial responses to imatinib; wild-type and KIT exon 9 mutations are associated with a higher rate of rapid imatinib failure due to resistance. 1,11,12 Acquired resistance to imatinib is most commonly caused by secondary KIT mutations in other exons, selected during TKI therapy.1,11,13,14

Nilotinib is a selective TKI targeting ABL1/BCR-ABL1, KIT, PDGFRα and –β, and DDR-1 and -2; it has potency similar to that of imatinib against KIT and PDGFRs.2,12,15 In vitro, nilotinib also exhibits activity against certain imatinib-resistant KIT mutations.12 Nilotinib has been evaluated in patients with advanced GISTs following failure of previous therapies, but first-line nilotinib therapy has not been studied in a controlled clinical trial.16–18 To test whether nilotinib might confer superior outcomes when used earlier in the course of disease, this trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of nilotinib vs imatinib as first-line therapy for advanced GISTs. We report the final analysis of the core study as well as a subgroup analysis of efficacy outcomes based on KIT mutation subsets.

Methods

Patients

Patients were aged ≥18 years, had a histologically confirmed unresectable or metastatic GIST, and had received no prior systemic therapy for GIST or had experienced a recurrence of GIST ≥6 months after stopping adjuvant treatment with imatinib. In addition, patients had at least one measurable site of disease on computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging, as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors based on investigator assessment, a World Health Organization performance score of 0 to 2 (capable of self-care, but not any work), and normal organ, electrolyte, and marrow function. Active non-GIST malignancy within 10 years (except basal cell skin cancer and cervical carcinoma in situ) was not permitted. Patients could not have impaired cardiac function (eg, QTcF >450 msec, left ventricular ejection fraction <45%, complete left bundle branch block, clinically significant bradycardia [<50 beats per minute], history of myocardial function or unstable angina within 12 months). Bleeding disorders unrelated to cancer and known symptomatic brain metastases were not allowed. Predicted survival was not an eligibility criterion; however, prior studies demonstrated a median OS of 55 months in a similar patient population.6 An independent data monitoring committee (IDMC) evaluated the preplanned interim analyses. The study done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines on Good Clinical Practice and was approved by ethics committees at each centre, and all patients provided written informed consent prior to any study-specific procedures defined in the protocol.

Procedures

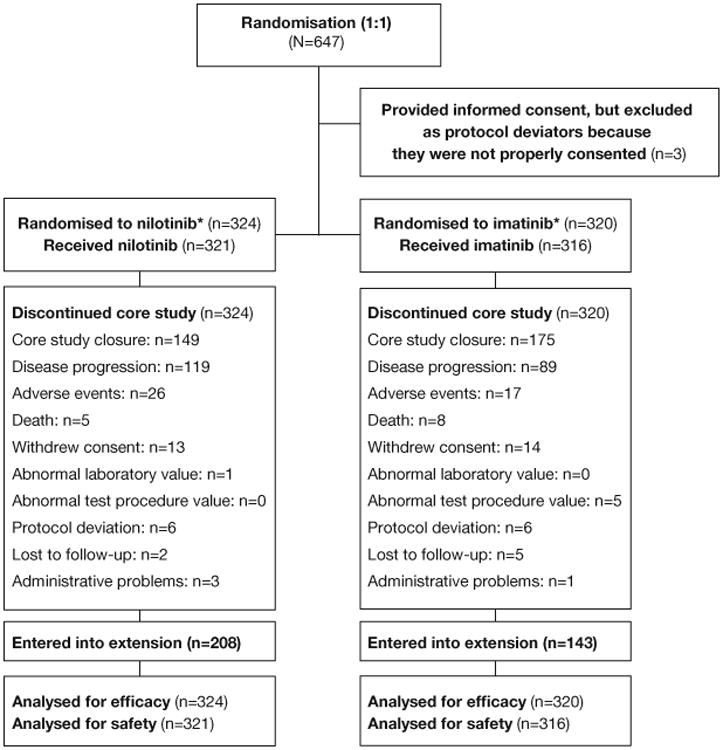

In this randomised, open-label, multicentre, two-arm, phase 3 study (figure 1; NCT00785785), eligible patients received oral nilotinib hydrochloride monohydrate (AMN107; Novartis Pharmaceuticals; East Hanover, NJ, USA) 400 mg twice daily or oral imatinib mesylate (STI571; Novartis Pharmaceuticals; East Hanover, NJ, USA) 400 mg once daily. In the imatinib arm, 400 mg twice daily was recommended for patients with a KIT exon 9 mutation. The original study design consisted of two periods: (1) a core study period lasting from the day of randomisation until disease progression (defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] v1.0),19 death, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal of consent, or discontinuation from the study for any other reason and (2) an optional extension period allowing patients with disease progression (per RECIST) in the core study to cross over to the other arm of the study and receive the alternative treatment.

Figure 1. CONSORT diagram.

A randomised, open label, multi-centre phase III study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of nilotinib vs imatinib in adult patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours (ENESTg1)—ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00785785.

Note: 11 patients were assigned to imatinib therapy (as forced randomization) because they signed an informed consent form prior to termination of patient accrual on April 8, 2011.

*Dose: nilotinib 400 mg twice daily; imatinib 400 mg once daily. Patients whose tumour has confirmed KIT exon 9 mutation before the study entry could start imatinib at 400 mg twice daily.

During a planned interim PFS analysis (data cutoff of November 2010), the futility boundary (1.111) was crossed and trends favoured imatinib. The PFS hazard ratio (HR) for nilotinib vs imatinib was 2.032, suggesting that nilotinib was unlikely to be found superior to imatinib. Thus, per IDMC recommendation, accrual was stopped in April 2011 and the protocol was further amended to allow nilotinib patients to switch to imatinib, even without disease progression. Patients in the nilotinib arm could continue nilotinib treatment in cases of investigator-determined benefit, unless individual health authorities required all nilotinib patients to be switched to imatinib. Patients who progressed while in the imatinib arm were no longer allowed to switch to nilotinib after the protocol amendment. All patients who experienced disease progression in the extension study entered the survival follow-up (if patient consented) until closure of the extension. After the extension study closes, patients still receiving benefit on nilotinib might be eligible to enrol in a separate study to maintain nilotinib treatment (figure A1).

Disease was evaluated by standard imaging (chest, abdomen, and pelvis computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) at baseline and every 3 months until disease progression. CT/MRI scans in the core study were evaluated both locally and centrally. Clinical decisions were made based on local review. Adjudications were performed by an independent radiologist in cases of discordance between local and central reads regarding dates of disease progression. Adjudicated central review data were used for analyses in this paper unless otherwise stated.

Tumour genotype (ie, mutations in KIT and PDGFRα) was examined both centrally and locally using archival tumour tissue samples obtained at diagnosis. Centrally assessed genotype data were used for mutation analyses. PFS, OS, and tumour response of nilotinib vs imatinib were compared according to mutation status: KIT exon 9, KIT exon 11, or PDGFRα; mutations other than these three types; or no detectable mutations in KIT or PDGFRα.

Laboratory values (ie, haematology and blood chemistry) were monitored monthly. Safety assessments consisted of evaluating adverse events (AEs) according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0, and regular monitoring of laboratory tests, vital signs, and cardiac (echocardiograms and electrocardiogram) assessments.

Dose modifications were allowed in the case of haematologic or nonhaematologic toxicity. In general, study drug was withheld until AEs resolved to grade 1 or better. Then, patients who recovered within 14 days resumed normal doses and patients who recovered within 15-28 days received a reduced dose (300 mg once daily in the nilotinib arm; 300 mg once daily for patients in the imatinib arm receiving 400 mg once daily; 600 mg once daily for patients in the imatinib arm receiving 400 mg twice daily). Patients who did not recover to grade 1 or better within 28 days discontinued the study, recurred with the same toxicity upon reinitiating treatment, or experienced grade 3/4 pancreatitis discontinued the study. For additional details, please see table A1.

Randomisation and masking

In this open-label trial, patients were randomised 1:1 to receive either nilotinib or imatinib. A patient randomization list, stratified by prior adjuvant imatinib therapy, was generated using a validated interactive voice response system to automatically assign patient numbers to the treatment groups; these treatment groups were linked to medication numbers. A separate medication list was generated under the responsibility of the study sponsor using a validated automated system to randomly assign medication numbers to medication packs containing each of the study drugs. The randomization scheme for patients was reviewed and approved by a member of the Biostatistics Quality Assurance Group. Because this was an open-label trial, blinding was not applicable, but measures were taken to minimize potential bias. Access to randomization information was limited to employees and designated agents of the study sponsor. The clinical team and statisticians were masked when possible to minimise bias, particular for all dosing information. Independent central reviewers were also blinded. Treatment allocation data were masked until accrual ended in April 2011.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was PFS—defined as disease progression (per adjudicated review) or death. Secondary endpoints included OS, overall response rate (ORR), disease control rate, safety, and tolerability. The relationship between tumour response and GIST genotype was evaluated as an exploratory objective.

Statistical analyses

The original planned target enrolment was 736 patients, calculated based on testing the assumption of superiority of nilotinib vs imatinib (HR 0.71; median PFS 28 vs 20 months, respectively). With this sample size, the study had 90% power to detect superiority with one-sided type I error of 2.5%. There were 2 planned interim analyses (1 for futility, when 75 PFS events occurred and 1 for superiority when 225 PFS events occurred), with final analysis after 375 PFS events. Because accrual ended early following the first interim analysis for futility, only 644 patients were included in the final analysis of the core study. With a data cutoff of October 17, 2012 (the last patient's last core study visit), the final analysis includes data from the period following the interim analysis, when the study design was changed to allow patients to switch from nilotinib to imatinib even without disease progression.

The full-analysis set, used for all efficacy assessments, included all randomized patients per the assigned treatment at randomization. The safety set, used for safety assessments, included all patients who received at least one dose of study medication, based on the treatment actually received. All assessments followed the intent-to-treat principle. For most endpoints, only data from the core study were analysed; however, the OS analysis included data from the extension study. Patients were considered non-assessable (or unknown response) per RECIST criteria for evaluating target and non-target lesions. 19 PFS and OS data are presented using Kaplan-Meier curves. The HRs with 95% CIs were estimated from a Cox regression model stratified by randomisation strata. Following the interim analysis, no further tests for superiority could be performed; therefore, P values are not presented. The same methods were used in the exploratory analysis of patients with centrally evaluable data on GIST mutational subtypes. No formal check for the proportional hazards assumption was performed because both the interim and follow-up analyses clearly indicated the nonsuperiority of nilotinib, and checking the assumptions would not affect this conclusion. SAS version 9.3 software was used to perform statistical analyses.

Informative censoring is censoring that is not independent of the patient's disease state.20 In this study, there were two potential causes for informative censoring. First, informative censoring can occur in open-label trials that use central review to evaluate PFS; patients with PFS events by local evaluation (leading to withdrawal or crossover) may not be considered progressors when later assessed by central review.21,22 That is, these patients would be censored in centrally reviewed PFS analyses, potentially overestimating PFS in one study arm. Thus, sensitivity analyses based on different tumour response review sources (local, central, or adjudicated central) were performed overall and for the mutation subgroups. Second, the study amendment after the interim analysis (allowing patients to switch to imatinib even without experiencing progression) could result in overestimation of the PFS rates for nilotinib. Thus, sensitivity analyses of PFS ignoring response data after the interim analysis were performed. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00785785.

Role of the funding source

This study and manuscript were supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. The study sponsor designed the study, managed the clinical trial database, provided statistical analysis, and funded medical editorial assistance.

Results

Interim analysis results

The interim futility analysis was based on 397 evaluable patients. The results showed that more progression events occurred in the nilotinib arm than in the imatinib arm (48/196 and 28/201, respectively); the HR was 2.032 (95% CI 1.273–3.243). More deaths occurred in the nilotinib arm than in the imatinib arm (17/196 and 7/201, respectively); the HR was 2.66 (95% CI 1.1103–6.416), in favour of the imatinib arm. Based on these results, trial accrual was terminated early and the protocol was amended to close the study.

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

Because accrual stopped early, 647 patients were enrolled in the study between March 16, 2009, and April 21, 2011. Three patients who provided consent using an incorrect consent form were excluded from all analyses; seven patients did not receive any study drug and were excluded from safety analyses (figure 1). As of October 17, 2012 (median 28.0 months since randomisation; interquartile range, 23.1-33.1 months), all patients had discontinued core treatment. By then, 351 patients (imatinib, n=143; nilotinib, n=208) entered the extension study and 293 patients (imatinib, n=177; nilotinib, n=116) discontinued core treatment and did not enter the extension study. The most frequently reported reasons for core study discontinuation in both arms were core study closure, disease progression, and AEs (figure 1).

Baseline characteristics were similar between the two treatment arms (table 1). The most common primary sites of GIST were the stomach and small intestine. Most patients had metastases in the liver and/or abdomen. In the imatinib and nilotinib arms, 201/320 (62.8%) and 216/324 (66.7%) of patients, respectively, received a gross resection of their primary tumour. The primary tumour was at least 5 cm in diameter in 163/320 (50.9%) and 183/324 (56.5%) in the imatinib and nilotinib arms, respectively. Overall, 401 of 644 patients (62.3%) had centrally evaluable KIT and PDGFRα mutational data. The frequencies of KIT and PDGFRα mutations were consistent with previous results1; KIT exon 11 was the most common mutation (imatinib, 141/320 [69.1%]; nilotinib, 125/324 [63.5%]).

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics.

| Mutational analysis set | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Full analysis set | KIT exon 9 | KIT exon 11 |

KIT/PDGFRα wild-type |

Other | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Characteristic | Nilotinib (n=324) |

Imatinib (n=320) |

Nilotinib (n=24) |

Imatinib (n=26) |

Nilotinib (n=125) |

Imatinib (n=141) |

Nilotinib (n=13) |

Imatinib (n=16) |

Nilotinib (n=9) |

Imatinib (n=4) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Median (range) age, years | 59.0 (18–84) | 59.0 (18–88) | 57.5 (33–80) | 62.5 (42–82) | 60.0 (27–84) | 59.0 (27–88) | 47.0 (18–71) | 59.5 (25–76) | 57.0 (47–67) | 72.5 (66–75) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Male, n (%) | 179 (55.2) | 187 (58.4) | 14 (58.3) | 12 (46.2) | 61 (48.8) | 82 (58.2) | 7 (53.8) | 7 (43.8) | 7 (77.8) | 2 (50.0) |

|

| ||||||||||

| WHO performance status, n (%) | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| 0 | 204 (63.0) | 194 (60.6) | 16 (66.7) | 21 (80.8) | 87 (69.6) | 90 (63.8) | 10 (76.9) | 10 (62.5) | 8 (88.9) | 4 (100.0) |

|

|

||||||||||

| 1 | 106 (32.7) | 112 (35.0) | 8 (33.3) | 5 (19.2) | 34 (27.2) | 44 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (37.5) | 1 (11.1) | 0 |

|

|

||||||||||

| 2 | 11 (3.4) | 9 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 4 (3.2) | 6 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Missing | 3 (0.9) | 5 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Primary GIST site, n (%) | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Stomach | 103 (31.8) | 123 (38.4) | 0 | 3 (11.5) | 43 (34.4) | 51 (36.2) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (37.5) | 5 (55.6) | 3 (75.0) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Small intestine | 117 (36.1) | 98 (30.6) | 17 (70.8) | 13 (50.0) | 45 (36.0) | 52 (36.9) | 7 (53.8) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Large intestine | 17 (5.2) | 21 (6.6) | 0 | 3 (11.5) | 8 (6.4) | 8 (5.7) | 0 | 2 (12.5) | 2 (22.2) | 0 |

|

|

||||||||||

| Other | 81 (25.0) | 69 (21.6) | 6 (25.0) | 6 (23.1) | 27 (21.6) | 27 (19.1) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (18.8) | 0 | 1 (25.0) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Unknown | 6 (1.9) | 9 (2.8) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Median (range) time since diagnosis of primary site to study randomisation, months | 7.3 (0–256) | 4.7 (0–287) | 8.6 (1–54) | 3.2 (0–91) | 5.8 (0–141) | 9.5 (0–120) | 8.8 (1–89) | 6.1 (1–120) | 24.0 (2–84) | 8.2 (1–90) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Site of metastasis, n (%) | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Lung | 22 (6.8) | 35 (10.9) | 2 (8.3) | 5 (19.2) | 11 (8.8) | 5 (3.5) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (25.0) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Liver | 196 (60.5) | 193 (60.3) | 15 (62.5) | 10 (38.5) | 71 (56.8) | 84 (59.6) | 9 (69.2) | 9 (56.3) | 5 (55.6) | 3 (75.0) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Abdomen | 97 (29.9) | 95 (29.7) | 9 (37.5) | 15 (57.7) | 38 (30.4) | 41 (29.1) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (18.8) | 5 (55.6) | 1 (25.0) |

|

|

||||||||||

| Other | 77 (23.8) | 89 (27.8) | 6 (25.0) | 6 (23.1) | 29 (23.2) | 32 (22.7) | 5 (38.5) | 5 (31.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Patients with evaluable mutation data, n (%)* | 197 (60.8) | 204 (63.8) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Tumour mutation type, n (%)† | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| KIT exon 9 | 24 (12.2) | 26 (12.7) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| KIT exon 11 | 125 (63.5) | 141 (69.1) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| KIT exon 13 | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| KIT exon 17 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| PDGFRα exon 12 | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| PDGFRα exon 18 | 6 (3.0) | 4 (2.0) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| PDGFRα p.D842V | 4 (2.0) | 3 (1.5) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| KIT/PDGFRα wild-type | 13 (6.6) | 16 (7.8) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Incomplete data | 26 (13.2) | 17 (8.3) | ||||||||

GIST=gastrointestinal stromal tumour. PDGFR=platelet-derived growth factor receptor. WHO=World Health Organization.

Mutation data were analysed centrally. Chinese patients did not have centrally evaluable mutation data.

The denominator of % is the number of patients who had centrally evaluable mutation data.

PFS and OS

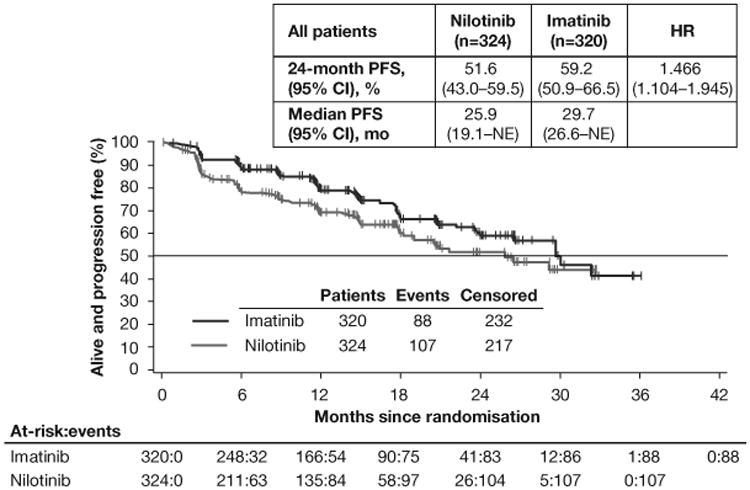

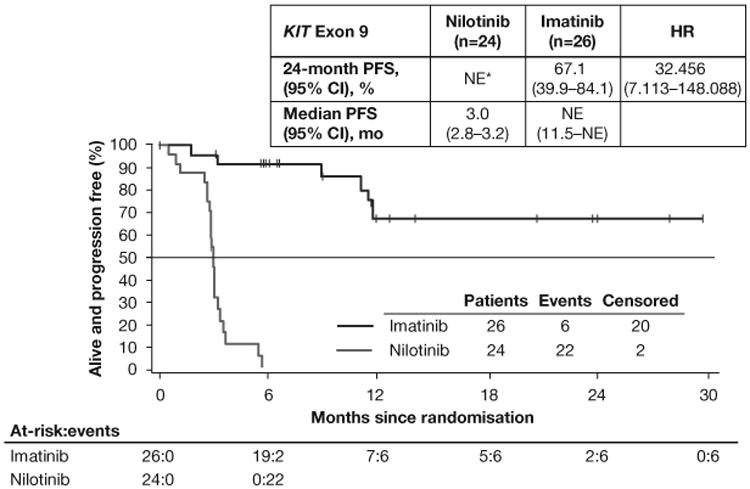

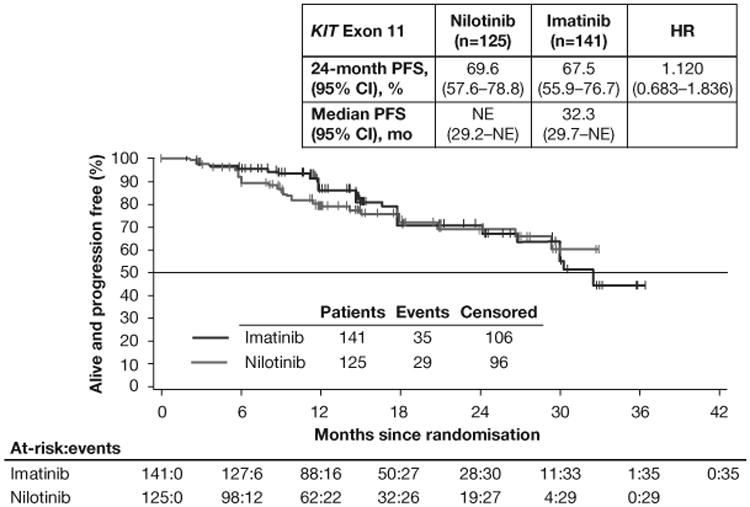

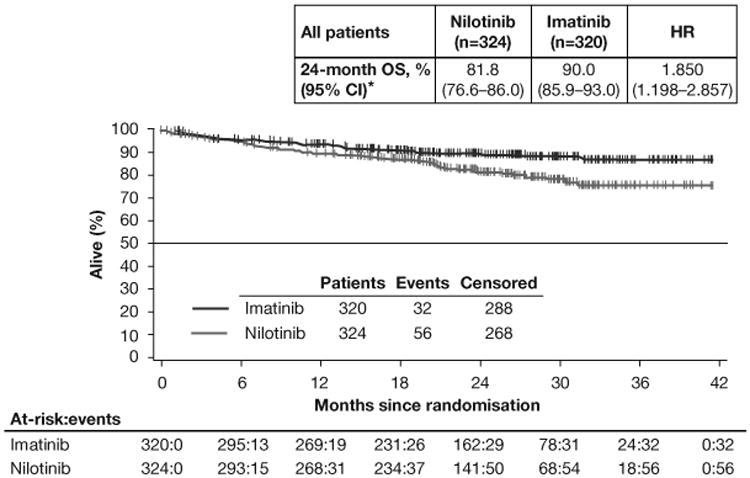

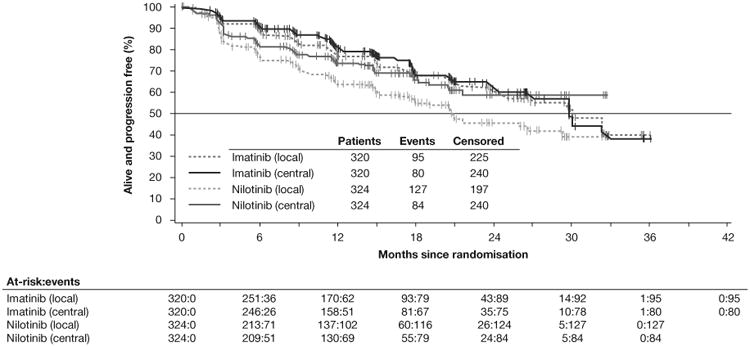

Final analysis of the full population showed substantially fewer PFS events in the imatinib (88 events; n=320) than in the nilotinib (107 events; n=324) arm. PFS at 24 months was higher in the imatinib (59.2% [95% CI 50.9%–66.5%]) than in the nilotinib (51.6% [95% CI 43.0%–59.5%]) arm; HR 1.466 (95% CI 1.104–1.945; figure 2A). Fewer OS events occurred in the imatinib (32 deaths; n=320) than in the nilotinib (56 deaths; n=324) arm. The 24-month OS rates were 90.0% (95% CI 85.9%–93.0%) in the imatinib arm and 81.8% (95% CI 76.6%–86.0%) in the nilotinib arm (HR 1.850 [95% CI 1.198–2.857]; figure 3A).

Figure 2. PFS.

PFS by adjudicated central review in the full-analysis set (A) and in the subsets of patients with KIT exon 9 mutations (B) or KIT exon 11 mutations (C). Following the interim analysis and decision to stop recruitment for futility, no subsequent formal inferences could be made; therefore, P values are not presented. *All exon 9 mutants on nilotinib had a PFS event or censoring within 6 months. HR=hazard ratio. PFS=progression-free survival. NE=not estimable.

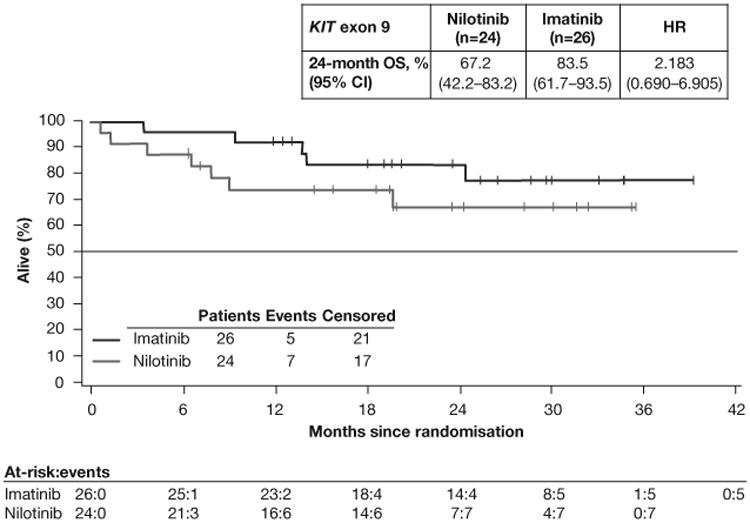

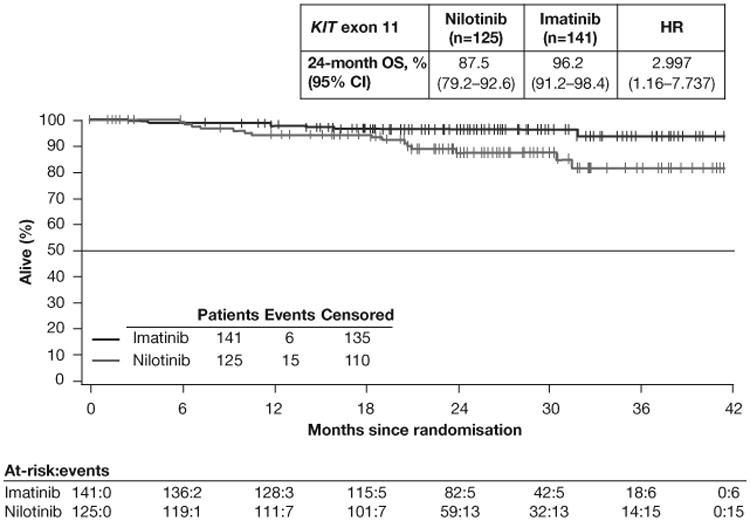

Figure 3. OS.

OS in the full-analysis set (A) and in the subsets of patients with KIT exon 9 mutations (B) or KIT exon 11 mutations (C). HR=hazard ratio. OS=overall survival. Median OS was not reached in either arm in the overall population or in the mutation subgroups.

Consistent with prior studies, PFS differed according to GIST mutation subtypes (table A2). In the KIT exon 9 subgroup, 24-month PFS rates were higher in the imatinib arm than in the nilotinib arm (imatinib [n=26], 67.1%; nilotinib [n=24], nonestimable [all patients had a PFS event or censoring within 6 months]; HR 32.456 [95% CI 7.113–148.088]; figure 2B). In the KIT exon 11 subgroup, 24-month PFS rates were roughly similar in the imatinib and nilotinib arms (imatinib [n=141], 67.5%; nilotinib [n=125], 69.6%; HR 1.120 [95% CI 0.683–1.836]; figure 2C).

OS at 24 months was better with imatinib than with nilotinib in patients with KIT exon 9 mutations (imatinib [n=26], 83.5%; nilotinib [n=24], 67.2%; HR 2.183 [95% CI 0.690–6.905]; figure 3B) and KIT exon 11 mutations (imatinib [n=141], 96.2%; nilotinib [n=125], 87.5%; HR 2.997 [95% CI 1.161–7.737]; figure 3C). These rates were also higher with imatinib than with nilotinib for patients with wild-type KIT and PDGFRα (imatinib [n=16], 73.9%; nilotinib [n=13], 50.8%; HR 1.864 [95% CI 0.561–6.194]; table A2). For patients with other mutations, OS rates were comparable in both arms (imatinib [n=4], 75.0%; nilotinib [n=9], 77.8%; HR 1.463 [95% CI 0.131–16.381]).

Sensitivity analyses of PFS to assess impact of informative censoring

The size of the treatment effect estimate for PFS on the full population differed somewhat depending on the data source. In the final analysis of the overall population, HRs (95% CI) for nilotinib vs imatinib using local, central, and adjudicated reviews were 1.621 (1.241-2.116), 1.248 (0.918-1.697), and 1.466 (1.104-1.945), respectively (table 2). Local reviewers declared PFS events earlier than central reviewers in the nilotinib arm; this effect was not observed in the imatinib arm (figure 4). Better results were observed consistently in the imatinib arm across all three review methods. Similarly, in the KIT exon 9 subgroup, the PFS results for the imatinib group were much better using any of the three review methods; HRs (95% CI) were 40.921 (5.190-322.661), 31.026 (6.805-141.453), and 32.456 (7.113-148.088), respectively. In contrast, there were large differences in the PFS treatment effect estimate in the KIT exon 11 group using the three review methods; HRs (95% CI) were 1.479 (0.924-2.368), 0.649 (0.388-1.087), and 1.120 (0.683-1.836), respectively.

Table 2. Summary of progression-free survival (PFS) rates overall and in KIT exon 11–positive patients according to data source (adjudicated, local, or central review).

| Type of review | Sensitivity analysis: April 2011* | Final analysis: October 2012† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS events, n (%) | HR (95% CI) | PFS events, n (%) | HR (95% CI) | |||

| Overall | Nilotinib (n=324) | Imatinib (n=307) | Nilotinib vs imatinib | Nilotinib (n=324) | Imatinib (n=320) | Nilotinib vs imatinib |

| Adjudicated (primary) | 70 (21.6) | 45 (14.7) | 1.770 (1.212–2.584) | 107 (33.0) | 88 (27.5) | 1.466 (1.104–1.945) |

| Local | 80 (24.7) | 47 (15.3) | 1.953 (1.358–2.810) | 127 (39.2) | 95 (29.7) | 1.621 (1.241–2.116) |

| Central | 61 (18.8) | 45 (14.7) | 1.560 (1.057–2.302) | 84 (25.9) | 80 (25.0) | 1.248 (0.918–1.697) |

| KIT exon 11 | Nilotinib (n=125) | Imatinib (n=137) | Nilotinib vs imatinib | Nilotinib (n=125) | Imatinib (n=141) | Nilotinib vs imatinib |

| Adjudicated (primary) | 16 (12.8) | 15 (10.9) | 1.570 (0.765–3.224) | 29 (23.2) | 35 (24.8) | 1.120 (0.683–1.836) |

| Local | 18 (14.4) | 15 (10.9) | 1.715 (0.851–3.455) | 37 (29.6) | 33 (23.4) | 1.479 (0.924–2.368) |

| Central | 13 (10.4) | 23 (16.8) | 0.812 (0.408–1.616) | 22 (17.6) | 43 (30.5) | 0.649 (0.388–1.087) |

HR=hazard ratio.

To help evaluate the impact of design changes following the interim analysis, PFS in the final clean database was analysed by applying a new data cutoff at the time the interim analysis results were disclosed (April 2011).

These results are from the final analysis of the core study.

Figure 4. Progression-free survival of the full-analysis set by local and central review.

When ignoring data generated after the interim analysis (ie, censoring at April 2011), although the differences between review sources remained, an even higher PFS difference was observed in favour of imatinib for the overall population (table 2). Notably, the treatment effect in the KIT exon 11 subgroup was higher according to local, central, and adjudicated reviews when censored at April 2011; HRs were 1.715 (0.851-3.455), 0.812 (0.408-1.616), and 1.570 (0.765-3.224), respectively.

Tumour response

Overall, the ORR was 51.9% (95% CI 46.4%–57.3%) in the imatinib arm (n=320) and 42.3% (95% CI 36.9%–47.7%) in the nilotinib arm (n=324); results were similar using local, central, or adjudicated review (table A4). ORRs were also higher in the imatinib arm than in the nilotinib arm for nearly all mutation subgroups (table A5). In the KIT exon 9 subgroup, the ORR was 34.6% (95% CI 16.3%–52.9%) in the imatinib arm (n=26); no patients achieved objective response in the nilotinib arm (n=24). In the KIT exon 11 subgroup, tumour response was also better in the imatinib (n=141; 68.8% [95% CI 61.1%–76.4%]) than in the nilotinib (n=125; 57.6% [95% CI 48.9%–66.3%]) arm. Conclusions regarding patients with other mutations are limited due to small sample sizes.

Safety and tolerability data

The median (range) duration of study drug exposure was 14.9 (0.4–37.0) months in the imatinib arm and 11.8 (0.1–32.7) months in the nilotinib arm. Median dose intensity was 400.0 (range, 91–783) mg in the imatinib arm and 790.0 (range, 337–800) mg in the nilotinib arm. Of the 26 patients in the imatinib arm who had KIT exon 9 mutations, 15 patients received the 400 mg once daily dose and 11 patients received the 400 mg twice daily dose. Study discontinuation because of AEs occurred in 17/320 patients (5.3%) in the imatinib arm and in 26/324 patients (8.0%) in the nilotinib arm, most commonly due to hyperbilirubinaemia (imatinib vs nilotinib, 0 [0%] vs 4 [1.2%]), vomiting (0 [0%] vs 3 [0.9%]), anaemia (2 [0.6%] vs 1 [0.3%]), and neutropenia (3 [0.9%] vs 0 [0%]). Dose reduction was reported in 9 patients (2.8%) in the imatinib arm and in 94 patients (29.3%) in the nilotinib arm. The main reasons for reduction were AEs (imatinib, n=5; nilotinib, n=47) and dosing errors (imatinib, n=1; nilotinib, n=48). Most dosing errors were occasional missed doses that were not associated with AEs or scheduling conflicts; the frequency of dosing error days was < 1% of total treatment days. The increased frequency of dosing errors in the nilotinib arm was most likely due to the increased complexity of dosing (twice daily nilotinib instead of once daily imatinib). Treatment interruption, mainly due to AEs, was reported in 139/320 patients (44.0%) in the imatinib arm and in 157/324 patients (48.9%) in the nilotinib arm.

Overall, in the core study, 11/320 patients (3.5%) in the imatinib arm and 13/324 patients (4.0%) in the nilotinib arm died on treatment or up to 28 days after the last dose of study drug. In the imatinib arm, seven deaths were due to disease progression and one each to jejunal perforation, alcoholic cirrhosis, pneumonia, and intracranial haemorrhage. In the nilotinib arm, nine deaths were due to disease progression and one each to cardiac arrest, sepsis, septic shock, and transfusion reaction. No treatment-related deaths were reported.

AEs were reported in 293/320 patients (92.7%) in the imatinib arm and in 307/324 patients (95.6%) in the nilotinib arm. The most frequently reported AEs for imatinib were nausea, diarrhoea, peripheral oedema, fatigue, vomiting, and abdominal pain (table 3). The most frequently reported AEs for nilotinib were rash, nausea, abdominal pain, fatigue, and hyperbilirubinaemia. Grade 3/4 AEs were reported in 139 patients (44.0%) in the imatinib arm and in 128 patients (39.9%) in the nilotinib arm. The most common grade 3/4 AEs for imatinib were hypophosphataemia, anaemia, abdominal pain, elevated lipase level, neutropenia, and diarrhoea. The most common grade 3/4 AEs for nilotinib were anaemia, elevated lipase level, elevated alanine aminotransferase level, abdominal pain, and hyperbilirubinaemia. The most common serious AEs in both arms was abdominal pain (imatinib, n=11 [3.5%]); nilotinib, n= 14 [4.4%]). Grade 3/4 cardiac AEs were observed in seven patients (2.2%) in the imatinib arm (two cardiorespiratory arrests, two cases of supraventricular tachycardia, and one case each of acute myocardial infarction [MI], arrhythmia, and atrial fibrillation) and in five patients (1.6%) in the nilotinib arm (one each pericardial effusion, cardiac arrest, and diastolic dysfunction and two MIs—one acute).

Table 3. Adverse events reported up to 28 days after study drug discontinuation (safety population).

| Grade 1/2 events occurring in ≥10% in either treatment arm and all grade 3-5 events* | Nilotinib (n=321) | Imatinib (n=316) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1/2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 1/2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Rash | 86 (26.8) | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 44 (13.9) | 3 (0.9) | 0 |

| Nausea | 66 (20.6) | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 102 (32.3) | 3 (0.9) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 59 (18.4) | 4 (1.2) | 0 | 63 (19.9) | 3 (0.9) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 57 (17.8) | 10 (3.1) | 1 (0.3) | 49 (15.5) | 12 (3.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 52 (16.2) | 8 (2.5) | 1 (0.3) | 10 (3.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 49 (15.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 24 (7.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 45 (14.0) | 6 (1.9) | 0 | 59 (18.7) | 6 (1.9) | 0 |

| Constipation | 42 (13.1) | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 21 (6.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Pruritus | 40 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 25 (7.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 38 (11.8) | 5 (1.6) | 0 | 46 (14.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Myalgia | 38 (11.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 15 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 37 (11.5) | 4 (1.2) | 0 | 96 (30.4) | 8 (2.5) | 1 (0.3) |

| Upper abdominal pain | 35 (10.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 13 (4.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 33 (10.3) | 0 | 0 | 13 (4.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Peripheral oedema | 30 (9.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 66 (20.9) | 3 (0.9) | 0 |

| ALT increased | 30 (9.3) | 11 (3.4) | 1 (0.3) | 12 (3.8) | 5 (1.6) | 0 |

| Weight decreased | 26 (8.1) | 0 | 0 | 17 (5.4) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Cough | 25 (7.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 20 (6.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Back pain | 24 (7.5) | 5 (1.6) | 0 | 16 (5.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Increased blood bilirubin | 24 (7.5) | 5 (1.6) | 0 | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 22 (6.9) | 4 (1.2) | 0 | 27 (8.5) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 22 (6.9) | 0 | 0 | 24 (7.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 22 (6.9) | 0 | 0 | 17 (5.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Anaemia | 18 (5.6) | 11 (3.4) | 7 (2.2) | 41 (13.0) | 10 (3.2) | 7 (2.2) |

| Arthralgia | 18 (5.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 12 (3.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 17 (5.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 14 (4.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| AST increased | 17 (5.3) | 4 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) | 11 (3.5) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 14 (4.4) | 6 (1.9) | 0 | 34 (10.8) | 19 (6.0) | 0 |

| Abdominal distension | 14 (4.4) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 10 (3.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Dyspepsia | 12 (3.7) | 0 | 0 | 10 (3.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Dyspnoea | 11 (3.4) | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 16 (5.1) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Anxiety | 11 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | 10 (3.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 10 (3.1) | 13 (4.0) | 2 (0.6) | 10 (3.2) | 11 (3.5) | 1 (0.3) |

| Urinary tract infection | 9 (2.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 12 (3.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Pollakiuria | 9 (2.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 7 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 13 (4.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase increased | 7 (2.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 7 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Face oedema | 6 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 41 (13.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Amylase increased | 6 (1.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 9 (2.8) | 4 (1.3) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 6 (1.9) | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 7 (2.2) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Haemorrhoids | 6 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (1.9) | 4 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalaemia | 5 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 13 (4.1) | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Vertigo | 5 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | 6 (1.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Blood glucose increased | 5 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Conjugated bilirubin increased | 5 (1.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Leukopenia | 4 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 31 (9.8) | 3 (0.9) | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 4 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Generalized rash | 4 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| White blood cell count decreased | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 16 (5.1) | 3 (0.9) | 0 |

| Haemoglobin decreased | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 12 (3.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Ascites | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Pericardial effusion | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Abnormal hepatic function | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Bronchitis | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Transaminases increased | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Hyperkalaemia | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Periorbital oedema | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 57 (18.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 30 (9.5) | 10 (3.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| Weight increased | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 8 (2.5) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Blood phosphorus decreased | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) | 0 | 8 (2.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperuricaemia | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Pain | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Paraesthesia | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Cellulitis | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Hyperlipasaemia | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Convulsion | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tumour haemorrhage | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Cataract | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 16 (5.1) | 4 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 5 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Dehydration | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphopaenia | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Respiratory tract infection | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal haemorrhage | 1 (0.3) | 5 (1.6) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Osteoporosis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Angina pectoris | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Infection | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Maculopapular rash | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Anal fissure | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Cholangitis | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hematemesis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Hypermagnesaemia | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Sepsis | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Periodontitis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Erythematous rash | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Acute renal failure | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Syncope | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Urticaria | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Generalized oedema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Blood uric acid increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Hypoglycaemia | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Lipase | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Cholestatic jaundice | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Sciatica | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Subileus | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Confused state | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Haematuria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Intra-abdominal haemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Post-procedural infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Scrotal oedema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Lung infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Lung infiltration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Fracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Cardio-respiratory arrest | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumour | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bile duct obstruction | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Abdominal infection | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Altered state of consciousness | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colon cancer | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colonic stenosis | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diastolic dysfunction | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lip and/or oral cavity cancer | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Loss of consciousness | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mesenteric vein thrombosis | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oropharyngeal candidiasis | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Overdose | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Peritonitis | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Polyarthritis | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ileus | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Hypocoagulable state | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Third nerve paralysis | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jaundice | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Septic shock | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Abdominal hernia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Abdominal mass | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Anal fistula | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Arrhythmia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Bladder cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Cataract operation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Duodenal obstruction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Venous embolism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Erythema multiforme | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Exfoliative rash | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Fibromyalgia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Gastric ulcer haemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal oedema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Granulocytopaenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Haemorrhagic anaemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Malignant lung neoplasm | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Metastases to liver | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Metastases to peritoneum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Multiple fractures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Myocardial ischemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Obesity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Osteomyelitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Peptic ulcer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Radiculopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Respiratory tract haemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Small intestine carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Tumour necrosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Urinary tract neoplasm | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Vena cava thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Venous thrombosis limb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Hypochromic anaemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Hypovolemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Ischemic stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Tumour excision | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Multi-organ failure | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Bacterial sepsis | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cerebral infarction | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cognitive disorder | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal obstruction | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mechanical ileus | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abnormal pancreatic enzymes | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory failure | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transfusion reaction | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Jejunal perforation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Metastatic pancreatic carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Portal hypertension | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Troponin increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Intestinal perforation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

No grade 5 adverse events were reported.

Discussion

The final analysis of the core study showed higher rates of PFS, ORR, and OS with imatinib than with nilotinib, both overall and in the KIT exon 9 subgroup. Patients with KIT exon 9 mutations in the imatinib group had the option of receiving imatinib 400 mg twice daily (ie, double the standard dose). An equivalent dose increase in the nilotinib arm was not possible because the maximum tolerated dose of nilotinib is 600 mg twice daily. All patients in the nilotinib arm received 400 mg twice daily; thus, doubling that standard dose to 800 mg twice daily would have induced unacceptable toxicity with a linear pharmacokinetic profile.23 Furthermore, although imatinib and nilotinib have similar potencies in cells harbouring mutations in KIT exon 9, exon 11, and exon 13,12,15 the compounds have different pharmacodynamic properties that might result in differences in intratumour drug levels.24–26 Additionally, estimated 24-month survival rates in the imatinib arm (PFS, 59.2%; OS, 90.0%) were better than in earlier clinical trials of imatinib in patients with advanced GISTs,4–6 suggesting that patients in this more recent trial were possibly treated earlier in the disease course and/or had less aggressive disease. For instance, in a pooled analysis of the S0033 and EORTC 62005 trials (MetaGIST), median time since diagnosis was 13.9 months (range, 0-359 mo).27 Here, median time since diagnosis was 4.7 months (range, 0-287) in the imatinib arm and 7.3 months (range, 0-256) in the nilotinib arm. Both in this study and a study of third-line nilotinib in patients with GIST,18 there was a discordance between central and adjudicated review. Previous studies have reported the difficulty in using unmodified RECIST for patients with GIST, particularly when metastatic lesions are involved.28–30 In future studies, using modified RECIST or alternate criteria may result in more consistent results among reviewers.

In the KIT exon 11 subgroup, although ORR and OS were better with imatinib, PFS was roughly similar in both study arms. The PFS results for the KIT exon 11 subgroup may be biased in favour of nilotinib due to informative censoring. In this group, local review detected more PFS events in the nilotinib arm (29.6% vs 23.4%), whereas central review detected fewer events in the nilotinib arm (17.6% vs 30.5%). Furthermore, in the overall population, local review resulted in earlier declaration of PFS events than central review in the nilotinib arm, but not in the imatinib arm. The discrepancy between central and local review for PFS indicates the potential biases in using local review to make clinical decisions rather than central review, particularly in an open-label trial. The bias seen with locally reviewed PFS was not observed for ORR.

Biochemical and x-ray crystallographic studies (Sandra Cowan-Jacob and Paul Manley, personal communication) indicate that nilotinib and imatinib bind to the same inactive conformation of the KIT protein (DFG-out), but nilotinib has greater affinity which might be the result of a tighter interaction with residues from the activation loop. This probably explains the similar efficacy of the two drugs in patients with KIT exon 11 mutations. The juxtamembrane region of KIT is involved in the autoregulation of KIT tyrosine kinase activity by modulating the conformation of the activation loop; based upon the results of this clinical study, one can speculate that KIT exon 9 mutations affect the conformation of the activation loop such that nilotinib binding is impacted to a greater extent than is imatinib binding, or alternatively that nilotinib simply is less effective at inhibiting the non-mutated intracellular structures which are shared between KIT exon 9 (extracellular) mutants and wild-type KIT protein.

In conclusion, nilotinib was not superior to imatinib in first-line therapy of patients with advanced GISTs. Both nilotinib and imatinib were well tolerated and the safety profiles of both drugs were consistent with prior clinical studies, mainly associated with nonhaematologic, gastrointestinal toxicities.4–6,16,18 This series represents one of the largest trial experiences of a TKI in advanced GIST patients besides imatinib. However, based on the data from this study and from prior studies in later lines of therapy, it cannot be recommended that nilotinib be broadly used in the treatment of GIST. Not yet defined patient stratification strategies are required to better identify patients with GIST who might derive benefit from nilotinib, although it has been suggested that nilotinib could be useful for patients intolerant of first-line imatinib with GIST not harbouring the KIT exon 9 mutation.31

Limitations of the study

Informative censoring occurs when results can be explained by censoring rather than a treatment effect. Informative censoring may have contributed to the lack of correlation observed between PFS and OS for patients with KIT exon 11 mutations. There were two sources of informative censoring: (1) the central review process in an open-label study, exacerbated by the presence of crossover,21,22 and (2) design changes following interim analysis.

The effect of using centrally reviewed PFS in an open-label study has been previously reported.21,22 In this study, for patients with KIT exon 11 mutations who were receiving nilotinib, there was a large difference in PFS by local vs central review, with the central review reporting relatively better PFS (table 2). In this group, patients who progressed by local assessment (conducted in real time) were permitted to cross over to imatinib treatment. Later, if central review did not classify patients as progressors, these patients would be censored in central review, artificially improving the apparent PFS for nilotinib compared with local review. Fewer PD events were declared based on the central review than on the local and adjudicated reviews in the nilotinib group, whereas more PD events were declared based on the central review than on the local and adjudicated reviews in the imatinib group. This suggests that the investigators tended to declare PD early in the nilotinib group, whereas the investigators in the imatinib group tended to declare PD much later (figure 4).

The design changes following the interim analysis could also have led to informative censoring because patients were allowed to continue with nilotinib if still receiving a benefit or to otherwise switch to imatinib before progression. If investigators learned that results favoured imatinib at the interim analysis (based on data up to April 4, 2011), they may have switched patients to imatinib, regardless of nilotinib's effect in those patients. As a result, the final analysis of PFS in the nilotinib arm (as of October 17, 2012) would be overestimated based on all review sources because these patients would be censored regardless of review source. This second source of informative censoring, due to changes in trial design, is supported by the sensitivity analyses of PFS ignoring data following the interim analysis, which generally favour imatinib (table 2). This observation suggests that the investigators were more likely to take the interim analysis results and the IDMC's recommendations into account when declaring PD events for patients on nilotinib.

The incorporation of crossover therapy into a study's design can also increase the likelihood of informative censoring, thereby contributing to the lack of correlation observed between PFS and OS for patients with KIT 11 mutations. The option of crossover therapy may inadvertently motivate an investigator to declare a PD event in order to switch to a perceivably more effective treatment. If informative censoring occurs equally between all treatment arms, the study results can still remain unbiased with regard to treatment effect. However, when there is more informative censoring in one treatment arm than in another, the treatment effect will be biased in favour of the arm with more censoring. This type of bias has been discussed previously in the literature, and it poses a real problem in the analysis of open-label trials.21,22 A sensitivity analysis for information censoring can account for any potential bias by removing the impact of subjective treatment decisions following the point at which the study became unmasked.

Thus, sensitivity analyses suggested the presence of informative censoring by both sources, leading to bias in favour of nilotinib. As such, the adjudicated PFS data should be interpreted with caution. In particular, PFS in patients harbouring KIT exon 11 should be viewed in the context of OS and ORR results, which favoured imatinib. Given the differences between locally and centrally reviewed PFS data, the central review process should be further evaluated in GIST.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Systematic Review

A thorough search of PubMed was used to evaluate existing data related to the treatment of advanced GIST. Continuous imatinib treatment has long been the standard of care for patients with advanced KIT+ GIST. Prior to the use of imatinib, median OS for patients with advanced GIST was approximately 20 months.9,32 Phase 2 and 3 clinical trials with imatinib showed prolonged survival in this patient population (median, 49-57 months).5,27 Despite the improved rates of survival with first-line imatinib, most patients still progress while on treatment (median, 19-24 months).5,27 While sunitinib and regorafenib are approved for treating second- and third-line GIST, imatinib is the only targeted treatment approved for patients with newly diagnosed advanced disease. Based on the available clinical trial data, there is an unmet need for developing new frontline treatment options with favourable benefit:risk profiles for patients with advanced GIST.

Interpretation

In ENESTg1, median PFS was 29.7 months in the imatinib arm (n=320) and 25.9 months in the nilotinib arm (n=324). Median OS was not reached in either arm of the study, but 24-month estimates were 90.0% and 81.8% in the imatinib and nilotinib arms, respectively. In general, PFS and OS in both arms were longer than what was reported in previous trials of imatinib and likely reflect the fact that patients are getting diagnosed earlier and have less extensive disease when starting treatment. Based on the results of this trial, first-line treatment with nilotinib cannot be recommended, but future studies may be able to identify specific subsets of patients who could benefit from this treatment.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. We thank Justin Potuzak, PhD (Chameleon Communications), and Pamela Tuttle, PhD (Articulate Science), for their medical editorial assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributions: All authors had access to the data, participated in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication and in article development, and had final approval of the content of this report.

Declaration of interests: Dr. Shen, Dr. Qin, Dr. Nosov, Dr. Wan, Dr. Srimuninnimit, Dr. Pápai have nothing to disclose. Dr. Blay reports grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from Bayer, grants and personal fees from Roche, grants and personal fees from GSK, outside the submitted work. Dr. Kang reports grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. Dr. Rutkowski reports grants, personal fees and other from Novartis, grants from Pfizer, personal fees and other from Bayer, outside the submitted work. Dr. Trent reports being an advisor for Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Le Cesne reports personal fees from Pharmamar, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Novartis, outside the submitted work. Dr. Reichardt reports personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. Dr. Demetri reports grants to his primary employer, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) and personal consulting fees from Novartis, during the conduct of the study; grants to DFCI and personal fees from Bayer, grants to DFCI and personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from EMD Serono, personal fees from Sanofi, grants to DFCI and personal fees from Janssen Oncology, grants to DFCI and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Ariad, personal fees from Astra-Zeneca, personal fees and other from Blueprint Medicines, personal fees and other from Kolltan Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. Demetri is a co-inventor on patent “Use of Imatinib in GIST” with royalties paid from Novartis via the Oregon Health and Sciences University and DFCI. Dr. Novick, Ms. Taningco, Dr. Mo, and Mr. Green are employees of Novartis, Inc.

References

- 1.Corless CL. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: what do we know now? Mod Pathol. 2014;27(suppl 1):S1–16. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manley PW, Stiefl N, Cowan-Jacob SW, et al. Structural resemblances and comparisons of the relative pharmacological properties of imatinib and nilotinib. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:6977–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold JS, van der Zwan SM, Gonen M, et al. Outcome of metastatic GIST in the era before tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:134–42. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1127–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanke CD, Demetri GD, von Mehren M, et al. Long-term results from a randomized phase II trial of standard- versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:620–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, et al. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:626–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patrikidou A, Chabaud S, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Influence of imatinib interruption and rechallenge on the residual disease in patients with advanced GIST: results of the BFR14 prospective French Sarcoma Group randomised, phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1087–93. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perol D, Ray-Coquard I, Nguyen BB, et al. Explored prognostic factors for survival in patients with advanced GIST treated with standard dose imatinib (IM): results from the BFR14 phase III trial of the French Sarcoma Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl) abstr 10092. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231:51–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, Kim YS. Correlation of imatinib resistance with the mutational status of KIT and PDGFRA genes in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo T, Agaram NP, Wong GC, et al. Sorafenib inhibits the imatinib-resistant KITT670I gatekeeper mutation in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13:4874–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Blanke CD, et al. Molecular correlates of imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4764–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manley PW, Drueckes P, Fendrich G, et al. Extended kinase profile and properties of the protein kinase inhibitor nilotinib. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawaki A, Nishida T, Doi T, et al. Phase 2 study of nilotinib as third-line therapy for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer. 2011;117:4633–41. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montemurro M, Schoffski P, Reichardt P, et al. Nilotinib in the treatment of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours resistant to both imatinib and sunitinib. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2293–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichardt P, Blay JY, Gelderblom H, et al. Phase III study of nilotinib versus best supportive care with or without a TKI in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors resistant to or intolerant of imatinib and sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1680–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih W. Problems in dealing with missing data and informative censoring in clinical trials. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2002;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1468-6708-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming TR, Rothmann MD, Lu HL. Issues in using progression-free survival when evaluating oncology products. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2874–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dodd LE, Korn EL, Freidlin B, et al. Blinded independent central review of progression-free survival in phase III clinical trials: important design element or unnecessary expense? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3791–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2542–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prenen H, Guetens G, de Boeck G, et al. Cellular uptake of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors imatinib and AMN107 in gastrointestinal stromal tumor cell lines. Pharmacology. 2006;77:11–6. doi: 10.1159/000091943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsueh YS, Lin CL, Chiang NJ, et al. Selecting tyrosine kinase inhibitors for gastrointestinal stromal tumor with secondary KIT activation-loop domain mutations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu S, Mathijssen RH, de Bruijn P, Baker SD, Sparreboom A. Inhibition of OATP1B1 by tyrosine kinase inhibitors: in vitro-in vivo correlations. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:894–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Meta-Analysis Group (MetaGIST) Comparison of two doses of imatinib for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a meta-analysis of 1,640 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1247–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mabille M, Vanel D, Albiter M, et al. Follow-up of hepatic and peritoneal metastases of gastrointestinal tumors (GIST) under Imatinib therapy requires different criteria of radiological evaluation (size is not everything!!!) Eur J Radiol. 2009;69:204–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamin RS, Choi H, Macapinlac HA, et al. We should desist using RECIST, at least in GIST. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1760–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi H, Charnsangavej C, Faria SC, et al. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1753–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanda T, Ishikawa T, Takahashi T, Nishida T. Nilotinib for treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: out of the equation? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:1859–67. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.816676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graadt van Roggen JF, van Velthuysen ML, Hogendoorn PC. The histopathological differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumours. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:96–102. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.