Abstract

Conventional resting left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) assessments have limitations for detecting doxorubicin (DOX)-related cardiac dysfunction. Novel resting echocardiographic parameters, including 3-dimen-sional echocardiography (3DE) and global longitudinal strain (GLS), have potential for early identification of chemotherapy-related myocardial injury. Exercise “stress” is an established method to uncover impairments in cardiac function but has received limited attention in the adult oncology setting. We evaluated the utility of an integrated approach using 3DE, GLS, and exercise stress echocardiography for detecting subclinical cardiac dysfunction in early breast cancer patients treated with DOX-containing chemotherapy. Fifty-seven asymptomatic women with early breast cancer (mean 26 ± 22 months post-chemotherapy) and 20 sex-matched controls were studied. Resting left ventricular (LV) function was assessed by LVEF using 2-dimensional echocardiography (2DE) and 3DE and by GLS using 2-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography (2D-STE). After resting assessments, subjects completed cardiopulmonary exercise testing with stress 2DE. Resting LVEF was lower in patients than controls by 3DE (55 ± 4 vs. 59 ± 5 %; p = 0.005) but not 2DE (56 ± 4 vs. 58 ± 3 %; p = 0.169). 10 of 51 (20 %) patients had GLS greater than or equal to −17 %, which was below the calculated lower limit of normal (control mean 2SD); this patient subgroup had a mean 20 % impairment in GLS (−16.1 ± 0.9 vs. −20.1 ± 1.5 %; p < 0.001), despite similar LVEF by 2DE and 3DE compared to controls (p > 0.05). Cardiopulmonary function (VO2peak) was 20 % lower in patients than controls (p < 0.001). Exercise stress 2DE assessments of stroke volume (61 ± 11 vs. 69 ± 15 ml; p = 0.018) and cardiac index (2.3 ± 0.9 vs. 3.1 ± 0.8 1 min−1 m−2 mean increase; p = 0.003) were lower in patients than controls. Post-exercise increase in cardiac index predicted VO2peak (r = 0.429, p = 0.001). Resting 3DE, GLS, and exercise stress 2DE detect subclinical cardiac dysfunction not apparent with resting 2DE in post-DOX breast cancer patients.

Keywords: Adjuvant therapy, Breast cancer, Cardiotoxicity, Echocardiography, Stress testing

Introduction

Doxorubicin (DOX)-containing chemotherapy for early breast cancer causes dose-dependent myocardial injury, leading to progressive cardiac dysfunction and symptomatic heart failure (HF) [1]. The incidence of overt HF with anthracycline-containing regimens is 2–5 %, with corresponding rates of asymptomatic left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) impairments between 15 and 18 % [2, 3]. 10-year data in node-positive breast cancer found cardiac dysfunction (LVEF ≥20 % relative decline) in 15–17 % of patients, which is higher than previously reported [3]. As such, pre-DOX administration assessment of resting LVEF is recommended by both oncology and cardiology societies as standard of care for all early breast cancer patients [4–6].

In current practice, 2-dimensional echocardiography (2DE) is most frequently used to evaluate resting LVEF. This technique, however, has limited reproducibility and accuracy for assessment of left ventricular (LV) volumes and LVEF [7]. Moreover, resting LVEF measurements by 2DE and other conventional modalities [i.e., multi-gated acquisition (MUGA) scanning] principally assess load-dependent changes in LV cavity size that may not reflect actual myocardial systolic function [8] nor predict LVEF decline [9, 10] or overt HF [2, 11, 12]. Consequently, once LVEF declines are detected, significant myocardial injury has occurred [13, 14], and is likely irreversible [11, 12, 15]. However, no consensus exists on the optimal imaging technique or combination of techniques to detect cardiac dysfunction in the oncology setting [16].

Accordingly, the utility of several novel imaging techniques such as cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), 3-dimensional volumetric echocardiography (3DE), and 2D speckle-tracking echocardiography (2D-STE) to detect early myocardial injury and subclinical cardiac dysfunction has been investigated [7, 16]. In general, these techniques appear to provide superior diagnostic and prognostic information than 2DE LVEF. In adjuvant breast cancer, initial work during or immediately following DOX therapy indicates that 3DE provides superior accuracy and reliability in comparison to 2DE [17, 18], whereas 2D-STE detects impairments in myocardial systolic function despite preserved LVEF by 2DE [9, 10, 19–23].

Although current clinical guidelines recommend use of resting cardiac imaging modalities, additional tools are available that may provide complementary assessments of cardiac function in breast cancer patients. Application of “system stress” (via pharmacologic or exercise) is an established method to detect subclinical impairments in myocardial function and determination of contractile reserve is an independent predictor of prognosis beyond LVEF in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), although these methods have received limited attention in breast cancer therapy-related cardiotoxicity [24]. Moreover, increasing evidence suggests that DOX-related injury may extend beyond the heart to impact other components of the cardiovascular (CV) system [25–27]. For example, we previously found that despite normal resting LVEF, early breast cancer patients have significant and marked impairments in cardiopulmonary function (VO2peak) [28]. VO2peak provides a measure of global CV function and reserve capacity and is inversely correlated with CV and all-cause mortality in a broad range of adult populations, including cancer [29–32].

To the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the utility of an integrated approach of conventional and novel echocardiographic parameters in combination with “stress” methods to assess the scope of subclinical cardiac dysfunction or predict impaired VO2peak in a breast cancer setting. To address this question, here we compared the combined utility of novel resting echocardiographic parameters (i.e., 3DE and GLS) and exercise “stress” to conventional methods (i.e., resting 2DE) in breast cancer patients previously treated with DOX-containing chemotherapy and preserved LVEF. We hypothesized that (1) under resting conditions, novel echocardiography parameters would detect subclinical cardiac dysfunction, (2) under exercise “stress” conditions, further cardiac impairments would be revealed, and (3) the combination of these approaches would provide information beyond use of any single technique. It was also hypothesized that resting and exercise parameters would be significant predictors of VO2peak.

Methods

Study population and procedures

Fifty-seven (n = 57) asymptomatic women with histologically confirmed estrogen-receptor positive (ER+) and HER2-negative breast adenocarcinoma (stage IA-IIIC) previously treated with standard dose DOX-containing chemotherapy without HER2-directed therapies (e.g., trastuzumab) were enrolled between January, 2011 and January, 2012 at Duke University Medical Center (DUMC). All patients had preserved LVEF [i.e., ≥50 %, according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (v4.03) [33]] by resting 2DE at study enrollment. Additional major eligibility criteria were (1) no recent documented cardiac disease and (2) no contraindications to a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) [34, 35]. Twenty sex-matched controls without history of malignancy, cardiac disease, or contraindications to CPET were also recruited from employees at DUMC for comparison purposes. The Institutional Review Board at DUMC approved the study and all participants provided written consent prior to the commencement of any study-related procedures. Following written consent, all participants completed the study assessments in the following order: (1) resting echocardiogram (2DE, 3DE, and 2D-STE), (2) symptom-limited CPET, to assess VO2peak, and (3) post-VO2peak stress echocardiogram (2DE).

Resting LV function by 2DE and 3DE

All 2DE and 3DE studies were performed with commercially available equipment (Vivid 7 or E9, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) by experienced sonographers. Following 2DE completion, a full volume dataset was acquired using a matrix array transducer with gated 4 beat acquisitions for assessments of LV volumes by 3DE. A 3DE acquisition of the entire LVwas generally performed in <10 s. All analyses were performed offline using EchoPac PC (version BT11, GE Medical, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Conventional 2DE measurements of LV dimensions, Doppler, and diastolic function parameters were performed and averaged over three cardiac cycles according to the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines [36–38]. LV volumes and LVEF by 2DE were calculated by the modified biplane Simpson's method from the apical 4-and 2-chamber views. LV volumes and LVEF by 3DE were determined by manipulating the full volume dataset to derive conventional apical 4-, 3-, and 2-chamber views using TomTec offline analysis software (4D LV-Function, Unterschleisheim, Germany). After selection of reference points, a 3D endocardial contour was automatically generated and manual adjustment was performed as necessary. The resultant end-diastolic (EDV) and end-systolic volumes (ESV) were used to calculate stroke volume (SV) and LVEF [39].

Resting longitudinal strain assessments

2D-STE longitudinal strain analyses were performed on high frame rate gray-scale images (60–90 frames/s) in the conventional apical 4-, 3-, and 2-chamber views [40]. For speckle tracking, the endocardial border was manually traced in end systole and the software automatically traced a region of interest including the entire myocardium. The integrity of speckle tracking was automatically detected and visually ascertained. In case of poor tracking, the region of interest tracing was manually readjusted. Segments with persistent inadequate tracking and studies with two or more segments inadequately tracked were excluded from analysis. Longitudinal strain was calculated as the change in length divided by the original length of the speckle pattern over the cardiac cycle and expressed as a percentage; myocardial longitudinal lengthening was represented as positive strain and shortening as negative strain [40]. Results of peak systolic longitudinal strain were automatically displayed as a 17-segment polar map model with segmental strain values and a mean global longitudinal strain (GLS) value for the entire LV.

CPET and post-VO2peak stress 2DE

VO2peak was evaluated using an incremental physician-supervised CPET with 12-lead ECG monitoring (Mac 5000, GE Healthcare) on a motorized treadmill (GE series 2000 Treadmill, GE Healthcare) with expired gas analysis (ParvoMedics TrueOne® 2400, Sandy, UT), according to established guidelines [34, 35]. Ninety percent of CPETs were of maximal effort given at least two of the following criteria were achieved: (1) obtained maximal predicted heart rate, (2) reached a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) ≥1.10, and/or (3) achieved volitional exhaustion. Within 30 s of VO2peak, subjects were placed in the supine position and 2DE grayscale images were obtained in the apical 4-, 3-, and 2-chamber views. Wall motion scoring index (WMSI) was calculated at rest and post-stress, using the 17 segment model, by adding the individual segment scores (1 = normal; 2 = hypokinesia; 3 = akinesia; 4 = dyskinesia) and dividing by number of segments scored [36]. Stress 2DE LV volumes and LVEF were calculated offline using the modified Simpson's biplane method. Cardiac output was calculated as the product of LV SV and heart rate, and was indexed to body surface area (BSA).

Reproducibility

All echocardiography measurements were performed offline by a single interpreter (MGK) in a blinded fashion. Intraobserver reproducibility was assessed by repeating measurements in 15 randomly selected subjects on a separate occasion. The intraobserver intraclass coefficients for resting 2D LVEF were 0.84 (95 % CI 0.61–0.94), 3D LVEF 0.89 (95 % CI 0.72–0.96), GLS 0.97 (95 % CI 0.92–0.99), and for resting and post-stress 2D SV 0.90 (95 % CI 0.74–0.96) and 0.95 (95 % CI 0.87–0.98), respectively.

Statistical analyses

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to assess overall differences in continuous variables between groups after adjustment for potential confounding covariates (e.g., age, hyperlipidemia, obesity, diabetes, smoking history, and exercise behavior). ANCOVA was also used to assess overall differences in change in SV, LVEF, and cardiac output/BSA (post-stress—rest) after adjustment for baseline value and covariates. Additional adjustment was performed for resting as well as peak blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) and heart rate to account for differences in hemodynamic loading conditions during cardiac function assessments. Fisher's exact tests were used to test differences in categorical variables. Pearson Correlations were used to examine the relationships among echocardiographic parameters (2D LVEF, 3D LVEF, GLS, and post-stress increase in cardiac index), DOX dose, and VO2peak. A two-sided significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. All statistical calculations were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

Patients' mean age and weight were 52 ± 10 years (range 28-72 years) and 75 ± 14 kg, respectively. The time from diagnosis and chemotherapy completion was 30 ± 22 and 26 ± 22 months, respectively. The median cumulative dose of DOX administered to patients was 240 mg m−2. Control subjects' mean age and weight were 57 ± 7 years (range 36-69 years) and 70 ±11 kg, respectively. Resting heart rate was 16 % higher in patients than controls (71 ±11 vs. 61 ± 9 bpm; p = 0.001). There were no significant differences between groups on any medical or demographic variables except age (p = 0.034; Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical, demographic, and cancer therapy characteristics.

| Variable | Patients | Controls | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 57 (74) | 20 (26) | |

| Age (years) | 51 ± 10 | 57 ± 7 | 0.034 |

| Weight (kg) | 74 ± 13 | 70 ± 11 | 0.146 |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | 27.4 ± 5.1 | 25.7 ± 4.1 | 0.171 |

| Heart rate beats (min−1) | 71 ± 11 | 61 ± 9 | 0.001* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 118 ± 12 | 113 ± 12 | 0.138* |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76 ± 8 | 72 ± 7 | 0.319* |

| Time since primary diagnosis, median (Q1, Q3) (months) | 29 (11, 48) | – | |

| Time since Anthracyclines, median (Q1, Q3) (months) | 20 (6, 45) | – | |

| Received Anthracyclines | |||

| Dose, DOX (mg m−2) | 257 ± 40 | – | |

| Dose, DOX, median (Q1, Q3) (mg m−2) | 240 (240, 300) | ||

| Dose, epirubicin (mg m−2) | 600† | – | |

| Additional therapy, no. (%) | |||

| Cytotoxic therapy‡ | 47 (82) | – | |

| Radiation | 45 (79) | – | |

| Endocrine therapy | 44 (77) | – | |

| Cardiac risk factors, no. (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 16 (28) | 1 (5) | 0.056 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 6 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.330 |

| Obesity | 12 (21) | 2 (10) | 0.334 |

| Diabetes | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Current and/or history of smoking | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.564 |

| Total exercise (min week−1) | 356 ± 556 | 422 ± 310 | 0.672 |

Values are mean ± SD, median (Q1, Q3), or n (%)

p adjusted for age, hyperlipidemia, obesity, diabetes, smoking, and total exercise

Only one patient received epirubicin, so no SD was calculated

Cytotoxic therapy includes taxol, xeloda, and abraxane

Resting 2DE, 3DE, and GLS LV function assessments

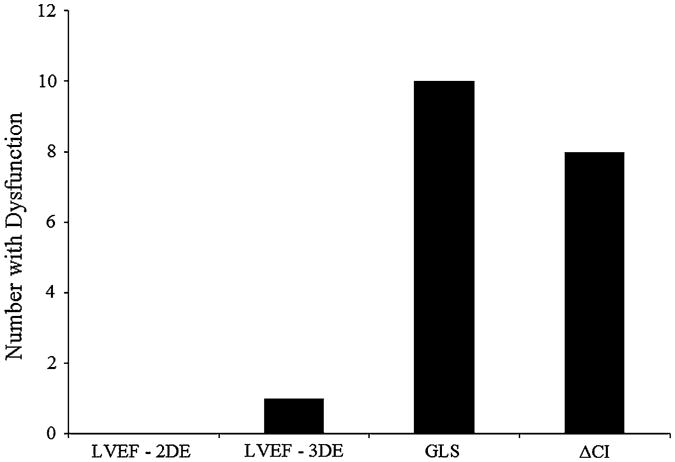

Of the 77 total subjects, adequate images for 2D LVEF, 3D LVEF, and GLS were available in 100, 92, and 91 %, respectively. Resting echocardiographic data are presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences in conventional measurements of LV dimensions and volumes as well as no significant differences in diastolic function parameters between patients and controls (all p > 0.05). Mean LVEF for both groups by either 2DE or 3DE was ≥55 %. Compared to controls, LVEF was significantly lower in patients by 3DE (55 ±4 vs. 59 ± 5 %; p = 0.005), but not 2DE (Fig. 1a). Mean GLS in patients was −18.9 ± 2, 6 % higher (more impaired LV shortening) than corresponding values for controls (p = 0.152). 10 of 51 (20 %) patients had GLS greater than or equal to −17 %; this patient subgroup had a mean 20 % impairment in GLS (−16.1 ± 0.9 vs. −20.1 ± 1.5 %; p < 0.001) despite similar resting 3D LVEF compared to controls (55 ± 4 vs. 59 ± 5 %; p = 0.564) (Fig. 1b). Cumulative DOX dose did not correlate with any resting assessments.

Table 2. Resting echocardiography data.

| Variable | Patients | Controls | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 57 | 20 | |

| LV dimensions/volumes | |||

| End-diastolic dimension (mm) | 42.8 ± 3.9 | 42.8 ± 4.1 | 0.254 |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 0.996 |

| 2D End diastolic volume (ml) | 110 ± 21 | 108 ± 24 | 0.617 |

| 2D SV (ml) | 61 ± 11 | 63 ± 14 | 0.239 |

| 3D End diastolic volume (ml) | 114 ± 23 | 111 ± 24 | 0.865 |

| 3D SV (ml) | 62 ± 11 | 65 ± 14 | 0.254 |

| Systolic function | |||

| 2D Ejection fraction (%) | 56 ± 4 | 58 ± 3 | 0.169 |

| 2D Cardiac output/BSA (1 min−1 m−2) | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 0.684† |

| 3D Ejection fraction (%) | 55 ± 4 | 59 ± 5 | 0.005 |

| GLS (%) | −18.9 ± 2.0 | −20.1 ± 1.5 | 0.152 |

| S wave velocity (cm s−1) | 8.3 ± 1.3 | 7.9 ± 1.0 | 0.654 |

| Wall motion score index | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.000 |

| Diastolic function | |||

| E/A ratio | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.927 |

| Deceleration time (ms) | 200 ± 28 | 197 ± 22 | 0.106 |

| E/e′ ratio | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 7.1 ± 2.5 | 0.506 |

| Myocardial performance index | 0.42 ± 0.13 | 0.42 ± 0.08 | 0.794 |

Values are mean ± SD

2D 2-dimensional, 3D 3-dimensional, BSA body surface area, S peak systolic myocardial tissue velocity, E transmitral peak early diastolic filling velocity, A transmitral peak late diastolic filling velocity, e′ peak early diastolic myocardial tissue velocity

p adjusted for age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate (HR), hyperlipidemia, obesity, diabetes, current and/or history of smoking, and total exercise

p for cardiac output adjusted for above variables except for HR

Fig. 1.

Novel resting and stress echocardiographic parameters in patients and controls. Scatter plots showing a 3D LVEF, b GLS, and c post-VO2peak stress—resting differences in cardiac index (Δ Cardiac Index). Solid horizontal lines represent the mean, while dotted line represents the lower limit of normal (defined as 50 % for LVEF; control mean—2SD for non-LVEF assessments)

VO2peak and post-VO2peak stress 2DE

Mean VO2peak in patients was 20 % lower compared to controls (24.5 ± 5.8 vs. 30.5 ± 6.8 ml kg−1 min−1; p < 0.001) (Table 3). Post-VO2peak stress 2DE was performed at 82 ± 8 % of peak HR; adequate stress images for interpretation were available in 76 % of subjects. SV and cardiac index were lower in patients compared to controls (61 ±11 vs. 69 ± 15 ml and 4.7 ± 1.0 vs. 5.3 ± 1.1 1 min−1 m−1, respectively, p < 0.05). Mean increase in post-stress cardiac index was 2.3 ± 0.9 1 min−1 m−1 in patients, 24 % lower than the 3.1 ± 0.8 1 min−1 m−1 mean increase in controls (p = 0.003) (Fig. 1c). Cumulative DOX dose did not correlate with any stress assessments.

Table 3. Cardiopulmonary function and post-VO2peak stress echocardiography data.

| Variable | Patients | Controls | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiopulmonary function | |||

| n | 57 | 20 | |

| HR, beats (min−1) | 168 ± 18 | 165 ± 13 | 0.658 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 153 ± 19 | 151 ± 25 | 0.791 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77 ± 9 | 75 ± 10 | 0.417 |

| VO2peak (ml kg−1 min−1) | 24.5 ± 5.8 | 30.5 ± 6.8 | <0.001 |

| VO2peak (1 min−1) | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| METpeak | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 8.7 ± 2.0 | <0.001 |

| RER | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.928 |

| Post-VO2peak stress echocardiography | |||

| n (%) | 42 (74) | 16 (80) | |

| HR, beats (min−1) | 140 ± 14 | 134 ± 13 | 0.570 |

| HR, max predicted (%) | 82 ± 8 | 83 ± 9 | 0.596 |

| End diastolic volume (ml) | 107 ± 20 | 113 ± 26 | 0.065 |

| SV (ml) | 61 ± 11 | 69 ± 15 | 0.018 |

| Δ SV (ml) | −1 ± 10 | 5 ± 10 | 0.161‡ |

| Cardiac output/BSA (1 min−1 m−2) | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 0.013† |

| Δ Cardiac output/BSA (1 min−1 m−2) | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 0.003†‡ |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 57 ± 5 | 61 ± 4 | 0.211 |

| Δ Ejection fraction (%) | 1 ± 6 | 3 ±4 | 0.283‡ |

| Wall motion score index | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.183 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%)

VO2peak peak oxygen consumption, CPET cardiopulmonary exercise test, MET metabolic equivalent, RER respiratory exchange ratio, BSA body surface area, Δ stress—resting difference

p adjusted for age, peak exercise systolic blood pressure (SBP), peak exercise diastolic blood pressure (DBP), peak exercise heart rate (HR), hyperlipidemia, obesity, diabetes, current and/or history of smoking, and total exercise

p for cardiac output adjusted for above variables except for peak exercise HR

p for change scores also adjusted for pre-score

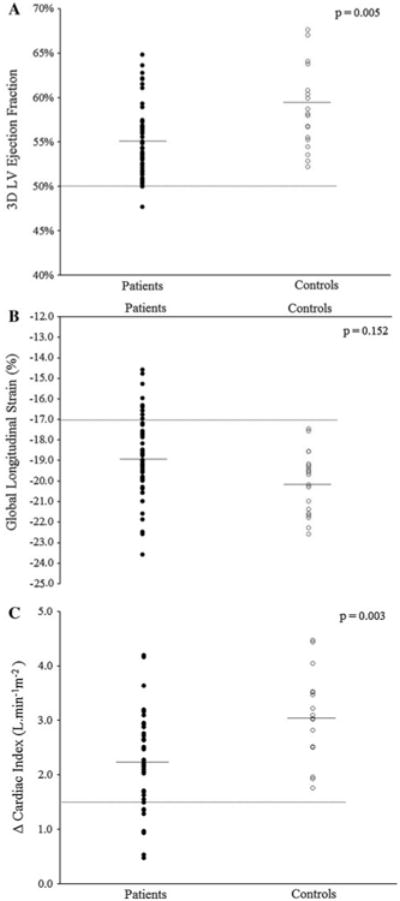

Integration of resting and stress echocardiography

The number of patients meeting “dysfunction” criteria [i.e., values below the lower limit of normal (LLN) (defined as control mean—2SD on non-LVEF assessments)] for each select echocardiographic parameter was (1) 2D LVEF (<50 %), n = 0, (2) 3D LVEF (<50 %), n = 1, (3) GLS (greater than or equal to −17 %), n = 10, and (4) post-stress increase in cardiac index (≤1.5 1 min−1 m−1), n = 8. A total of 18 patients (32 %) had at least one value below the LLN across the selected measures. Only one patient had values below the LLN on two measures (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Integrated resting and stress echocardiography. The number of patients meeting dysfunction criteria [i.e., LVEF <50 %; values below the lower limit of normal (defined as control mean—2SD) on non-LVEF assessments] for each select echocardiographic parameter. Only one patient met dysfunction criteria on multiple (two) parameters. Control subjects did not meet dysfunction criteria for any parameter. 2DE 2-dimensional echo, 3DE 3-dimensional echo, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, GLS global longitudinal strain, Δ CI post-VO2peak stress—resting difference in cardiac index

Echocardiography predictors of VO2peak

Significant univariate predictors of VO2peak (ml kg−1 min−1) were 2D LVEF (r = 0.252), 3D LVEF (r = 0.395), and post-stress increase in cardiac index (r = 0.429) (all p < 0.05). In multivariate analysis, post-stress increase in cardiac index was the only remaining significant predictor (p < 0.001; data not presented).

Discussion

As hypothesized, we found that despite preserved LVEF, resting GLS detected reduced myocardial systolic performance, with 20 % of patients demonstrating evidence of impaired GLS (i.e., greater than or equal to −17 %). Our results are consistent with those reported by other small studies in early breast cancer showing GLS impairments in the absence of LVEF decline during and within 1 year of DOX-containing adjuvant therapy [9, 10, 19–22]. Of relevance, Ho et al. [23] reported that 26 % of asymptomatic breast cancer patients (50 ± 22 months post-chemotherapy) had GLS values below the lower limit of the control group despite preserved LVEF. Our findings and that of Ho et al. indicate that myocardial systolic impairments may persist and/or develop well beyond the acute period of adjuvant therapy. However, while longitudinal strain is a potential subclinical marker of DOX-related cardiac dysfunction in early breast cancer, mean GLS values among patients in the majority of studies [9, 10, 19–21, 23] are within the normal range, [41] as observed in the present study. Nevertheless, among 546 unselected, consecutive individuals referred for echocardiography with mean GLS and LVEF values in the normal range, GLS was superior to LVEF for the prediction of long-term mortality [8]. As such, large-scale prospective studies assessing the clinical value of GLS in early breast cancer are warranted.

3DE assessment of resting LVEF is not routinely used in the oncology setting despite being superior to conventional 2DE in patients with and without cardiac disease [42]. We found that LVEF by 3DE was significantly lower (an absolute 4 % difference) in patients compared to controls, despite no differences by 2DE. In patients with early breast cancer, 3DE is superior to 2DE, and had similar accuracy to MUGA (with CMR as the gold standard) for LVEF assessment [17]. Similarly, in a prospective comparison of 2DE and 3DE in 56 breast cancer patients, Thavendiranathan et al. [18] found that the temporal variability of LVEF by 3DE was 5–6 % compared with 10–13 % by 2DE; more reliable detection is clinically important since an LVEF decline of ≥5 % that accompanies signs of HF confirms therapy-related cardiac dysfunction by existing criteria [16]. Accordingly, our findings, together with prior work in early breast cancer suggest that 3DE, where available, should be incorporated into standard echocardiographic exams among patients undergoing LVEF evaluation in the breast cancer adjuvant setting.

Exercise “stress” has been used in cardiology research and practice for more than three decades to detect sub-clinical impairments in cardiac function and obstructive CAD, but has received minimal attention in the adult oncology setting [24]. We found that stress 2DE revealed that LV SV and change in cardiac index (from rest) were reduced 12 and 24 %, compared to controls, respectively, suggesting that patients have impaired LV contractile reserve (LVCR). To the best of our knowledge, only two other studies have assessed LV functional response to “stress” (exercise or pharmacologic) in breast cancer patients. McKillop et al. [14] examined radionuclide-determined LVEF at rest and during graded exercise testing in 37 patients receiving DOX; exercise LVEF improved the sensitivity of detection of cardiotoxicity from 58 to 100 %. Civelli et al. [43] measured LVCR (defined as the difference between peak and resting LVEF) with low-dose dobutamine during and after high-dose chemotherapy in women with advanced breast cancer; an asymptomatic decline in LVCR of ≥5 units from baseline predicted LVEF decline to <50 %.

The importance of impaired augmentation of cardiac index is highlighted by its ability to not only identify subclinical cardiac dysfunction but also to predict global CV function (VO2peak). VO2peak provides a measure of CV reserve capacity - an entity not captured by current methods used in oncology clinical practice. The integrative nature of CV function suggests that adjuvant therapy-related cardiac damage likely occurs in conjunction with (mal)adaptation in other organ components [24–27]. Thus, tools with the ability to evaluate integrated cross-talk between CV organ components, like VO2peak, may arguably provide the best measure of therapy-related global CV effects in the setting of early breast cancer [24]. For example, we found that despite preserved LVEF ≥50 %, 130 breast cancer patients with a mean of 3 years following the completion of adjuvant therapy had VO2peak that was 22 % below that of age-matched women without a history of breast cancer [28]. Studies investigating the prognostic value of VO2peak to predict acute and late-occurring cardiac dysfunction and other CV events in early breast cancer patients are warranted.

A final exploratory purpose was to examine the utility of a multi-faceted approach incorporating the different echocardiographic parameters to assess the scope of cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction. Importantly, concordance was not significant as only 1 patient had simultaneous abnormal values on two parameters. In contrast, the integration of parameters, however, identified a total of 18 (32 %) patients with abnormal values (GLS detected 10 patients while the combination of GLS and post-stress change in cardiac index identified 17 patients with abnormal values). We contend that the discordance between methods provides support for the hypothesis that adjuvant therapy causes diverse adverse effects on the CV system [16, 25, 28], indicating that no single echocardiographic parameter likely provides full characterization of therapy-related cardiac dysfunction. This notion is supported by the findings of Tham et al. [27] who found no significant relationship between resting echocardiographic functional parameters, including GLS, and reduced VO2peak in 30 patients at least 2 years post-anthracycline therapy for pediatric malignancies. Thus, the application of novel resting echocardiographic parameters in combination with exercise-related assessments identified distinct patients with marked dysfunction; as such, the tools investigated here provided complementary as opposed to redundant information.

This study has several important limitations. Our findings are based on a relatively small sample size and are cross-sectional as opposed to prospective data. Interob-server reproducibility of echocardiographic measurements was not assessed; therefore, we cannot address clinical feasibility for the measures used in this study. There is no long-term data that subclinical cardiac dysfunction leads to clinical HF, and, therefore, the clinical implications of our findings are unknown. We were unable to obtain adequate resting and post-exercise measurements of novel echocardiography parameters in some study subjects. This was due to image quality in some patients, mainly due to breast surgery, postsurgical changes, and the presence of breast implants. Nevertheless, the feasibility for assessing novel parameters in this study was high, including >90 % for resting 3DE and GLS. We did not assess blood-based biomarkers (e.g., troponins) which have emerged as useful markers of early myocardial injury after adjuvant therapy in breast cancer [16] and shown incremental predictive power in combination with 2D-STE [9, 10]. We cannot rule out the contribution of CAD to LV dysfunction without invasive anatomical data; however, stress 2DE did not reveal new wall motion abnormalities.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that current approaches to evaluate cardiac function in breast cancer clinical trials and oncology practice may underestimate the extent and magnitude of subclinical cardiac dysfunction. If replicated, evaluation of resting cardiac function with LVEF by 3DE and GLS by 2D-STE as well as LVCR by stress 2DE may provide important complementary tools to assess both the acute and long-term cardiac impact of breast cancer adjuvant therapy.

Abbreviations

- ANCOVA

Analysis of covariance

- BSA

Body surface area

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CMR

Cardiac magnetic resonance

- CPET

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

- DOX

Doxorubicin

- EDV

End-diastolic volume

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- ESV

End-systolic volume

- GLS

Global longitudinal strain

- HER

Human epidermal growth factor receptor

- HF

Heart failure

- LLN

Lower limit of normal

- LV

Left ventricle/ventricular

- LVCR

Left ventricular contractile reserve

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MUGA

Multi-gated acquisition scan

- SV

Stroke volume

- 2DE

2-Dimensional echocardiography

- 2D-STE

2-Dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography

- 3DE

3-Dimensional echocardiography

- VO2peak

Peak oxygen consumption

- WMSI

Wall motion scoring index

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards Experiments performed in this study comply with the current laws of the United States.

Contributor Information

Michel G. Khouri, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3085, Durham, NC 27710, USA

Whitney E. Hornsby, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3085, Durham, NC 27710, USA

Niels Risum, The Heart Center, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Eric J. Velazquez, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3085, Durham, NC 27710, USA

Samantha Thomas, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3085, Durham, NC 27710, USA.

Amy Lane, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3085, Durham, NC 27710, USA.

Jessica M. Scott, NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, USA

Graeme J. Koelwyn, School of Health and Exercise Sciences, University of British Columbia, Kelowna, BC, Canada

James E. Herndon, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3085, Durham, NC 27710, USA

John R. Mackey, Cross Cancer Institute, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Pamela S. Douglas, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3085, Durham, NC 27710, USA

Lee W. Jones, Email: lee.w.jones@dm.duke.edu, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Box 3085, Durham, NC 27710, USA.

References

- 1.Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, Davis HL, Jr, Von Hoff AL, Rozencweig M, Muggia FM. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91(5):710–717. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-5-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2869–2879. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackey JR, Martin M, Pienkowski T, Rolski J, Guastalla JP, Sami A, Glaspy J, Juhos E, Wardley A, Fornander T, Hainsworth J, Coleman R, Modiano MR, Vinholes J, Pinter T, Rodriguez-Lescure A, Colwell B, Whitlock P, Provencher L, Laing K, Walde D, Price C, Hugh JC, Childs BH, Bassi K, Lindsay MA, Wilson V, Rupin M, Houe V, Vogel C. Adjuvant docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide in node-positive breast cancer: 10-year follow-up of the phase 3 randomised BCIRG 001 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(1):72–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70525-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eschenhagen T, Force T, Ewer MS, de Keulenaer GW, Suter TM, Anker SD, Avkiran M, de Azambuja E, Balligand JL, Brutsaert DL, Condorelli G, Hansen A, Heymans S, Hill JA, Hirsch E, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Janssens S, de Jong S, Neubauer G, Pieske B, Ponikowski P, Pirmohamed M, Rauchhaus M, Sawyer D, Sugden PH, Wojta J, Zannad F, Shah AM. Cardiovascular side effects of cancer therapies: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, Jacobs L, Schwartz C, Virgo KS, Hagerty KL, Somerfield MR, Vaughn DJ. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical evidence review on the ongoing care of adult cancer survivors: cardiac and pulmonary late effects. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3991–4008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Masoudi FA, Butler J, McBride PE, Casey DE, Jr, McMurray JJ, Drazner MH, Mitchell JE, Fonarow GC, Peterson PN, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American college of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christian JB, Finkle JK, Ky B, Douglas PS, Gutstein DE, Hoc-kings PD, Lainee P, Lenihan DJ, Mason JW, Sager PT, Todaro TG, Hicks KA, Kane RC, Ko HS, Lindenfeld J, Michelson EL, Milligan J, Munley JY, Raichlen JS, Shahlaee A, Strnadova C, Ye B, Turner JR. Cardiac imaging approaches to evaluate drug-induced myocardial dysfunction. Am Heart J. 2012;164(6):846–855. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanton T, Leano R, Marwick TH. Prediction of all-cause mortality from global longitudinal speckle strain: comparison with ejection fraction and wall motion scoring. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(5):356–364. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.862334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawaya H, Sebag IA, Plana JC, Januzzi JL, Ky B, Cohen V, Gosavi S, Carver JR, Wiegers SE, Martin RP, Picard MH, Gerszten RE, Halpern EF, Passeri J, Kuter I, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Early detection and prediction of cardiotoxicity in chemotherapy-treated patients. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(9):1375–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawaya H, Sebag IA, Plana JC, Januzzi JL, Ky B, Tan TC, Cohen V, Banchs J, Carver JR, Wiegers SE, Martin RP, Picard MH, Gerszten RE, Halpern EF, Passeri J, Kuter I, Scherrer-Crosbie M. Assessment of echocardiography and biomarkers for the extended prediction of cardiotoxicity in patients treated with anthracyclines, taxanes, and trastuzumab. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(5):596–603. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.973321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen BV, Skovsgaard T, Nielsen SL. Functional monitoring of anthracycline cardiotoxicity: a prospective, blinded, long-term observational study of outcome in 120 patients. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(5):699–709. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewer MS, Lenihan DJ. Left ventricular ejection fraction and cardiotoxicity: is our ear really to the ground? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1201–1203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ewer MS, Ali MK, Mackay B, Wallace S, Valdivieso M, Legha SS, Benjamin RS, Haynie TP. A comparison of cardiac biopsy grades and ejection fraction estimations in patients receiving Adriamycin. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2(2):112–117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKillop JH, Bristow MR, Goris ML, Billingham ME, Bockemuehl K. Sensitivity and specificity of radionuclide ejection fractions in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Am Heart J. 1983;106(5 Pt 1):1048–1056. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doyle JJ, Neugut AI, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Hershman DL. Chemotherapy and cardiotoxicity in older breast cancer patients: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8597–8605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khouri MG, Douglas PS, Mackey JR, Martin M, Scott JM, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Jones LW. Cancer therapy-induced cardiac toxicity in early breast cancer: addressing the unresolved issues. Circulation. 2012;126(23):2749–2763. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.100560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker J, Bhullar N, Fallah-Rad N, Lytwyn M, Golian M, Fang T, Summers AR, Singal PK, Barac I, Kirkpatrick ID, Jassal DS. Role of three-dimensional echocardiography in breast cancer: comparison with two-dimensional echocardiography, multiple-gated acquisition scans, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(21):3429–3436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thavendiranathan P, Grant AD, Negishi T, Plana JC, Popovic ZB, Marwick TH. Reproducibility of echocardiographic techniques for sequential assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and volumes: application to patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurcut R, Wildiers H, Ganame J, D'Hooge J, De Backer J, Denys H, Paridaens R, Rademakers F, Voigt JU. Strain rate imaging detects early cardiac effects of pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin as adjuvant therapy in elderly patients with breast cancer. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21(12):1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hare JL, Brown JK, Leano R, Jenkins C, Woodward N, Marwick TH. Use of myocardial deformation imaging to detect preclinical myocardial dysfunction before conventional measures in patients undergoing breast cancer treatment with trastuzumab. Am Heart J. 2009;158(2):294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negishi K, Negishi T, Haluska BA, Hare JL, Plana JC, Marwick TH. Use of speckle strain to assess left ventricular responses to cardiotoxic chemotherapy and cardioprotection. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fallah-Rad N, Walker JR, Wassef A, Lytwyn M, Bohonis S, Fang T, Tian G, Kirkpatrick ID, Singal PK, Krahn M, Grenier D, Jassal DS. The utility of cardiac biomarkers, tissue velocity and strain imaging, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in predicting early left ventricular dysfunction in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor II-positive breast cancer treated with adjuvant trastuzumab therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(22):2263–2270. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho E, Brown A, Barrett P, Morgan RB, King G, Kennedy MJ, Murphy RT. Subclinical anthracycline- and trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity in the long-term follow-up of asymptomatic breast cancer survivors: a speckle tracking echocardiographic study. Heart. 2010;96(9):701–707. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.173997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koelwyn GJ, Khouri M, Mackey JR, Douglas PS, Jones LW. Running on empty: cardiovascular reserve capacity and late effects of therapy in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(36):4458–4461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones LW, Haykowsky MJ, Swartz JJ, Douglas PS, Mackey JR. Early breast cancer therapy and cardiovascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(15):1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drafts BC, Twomley KM, D'Agostino R, Jr, Lawrence J, Avis N, Ellis LR, Thohan V, Jordan J, Melin SA, Torti FM, Little WC, Hamilton CA, Hundley WG. Low to moderate dose anthracycline-based chemotherapy is associated with early non-invasive imaging evidence of subclinical cardiovascular disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(8):877–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tham EB, Haykowsky MJ, Chow K, Spavor M, Kaneko S, Khoo NS, Pagano JJ, Mackie AS, Thompson RB. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis by T1-mapping in children with subclinical anthracycline cardiotoxicity: relationship to exercise capacity, cumulative dose and remodeling. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:48. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Muss HB, Pituskin EN, Scott JM, Hornsby WE, Coan AD, Herndon JE, 2nd, Douglas PS, Haykowsky M. Cardiopulmonary function and age-related decline across the breast cancer survivorship continuum. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2530–2537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta S, Rohatgi A, Ayers CR, Willis BL, Haskell WL, Khera A, Drazner MH, de Lemos JA, Berry JD. Cardiorespiratory fitness and classification of risk of cardiovascular disease mortality. Circulation. 2011;123(13):1377–1383. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.003236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gulati M, Pandey DK, Arnsdorf MF, Lauderdale DS, Thisted RA, Wicklund RH, Al-Hani AJ, Black HR. Exercise capacity and the risk of death in women: the St James Women Take Heart Project. Circulation. 2003;108(13):1554–1559. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091080.57509.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones LW, Watson D, Herndon JE, 2nd, Eves ND, Haithcock BE, Loewen G, Kohman L. Peak oxygen consumption and long-term all-cause mortality in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(20):4825–4832. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones LW, Hornsby WE, Goetzinger A, Forbes LM, Sherrard EL, Quist M, Lane AT, West M, Eves ND, Gradison M, Coan A, Herndon JE, Abernethy AP. Prognostic significance of functional capacity and exercise behavior in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;76(2):248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. [Accessed October 1, 2013];Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.03 (CTCAE) http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE.

- 34.American Thoracic Society, American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(2):211–277. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones LW, Eves ND, Haykowsky M, Freedland SJ, Mackey JR. Exercise intolerance in cancer and the role of exercise therapy to reverse dysfunction. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(6):598–605. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinones MA, Otto CM, Stoddard M, Waggoner A, Zoghbi WA Doppler Quantification Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. Recommendations for quantification of Doppler echocardiography: a report from the Doppler Quantification Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15(2):167–184. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.120202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth OA, Waggoner AD, Flachskampf FA, Pellikka PA, Evangelista A. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(2):107–133. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lang RM, Badano LP, Tsang W, Adams DH, Agricola E, Buck T, Faletra FF, Franke A, Hung J, de Isla LP, Kamp O, Kasprzak JD, Lancellotti P, Marwick TH, McCulloch ML, Monaghan MJ, Nihoyannopoulos P, Pandian NG, Pellikka PA, Pepi M, Roberson DA, Shernan SK, Shirali GS, Sugeng L, Ten Cate FJ, Vannan MA, Zamorano JL, Zoghbi WA American Society of Echocardiography, European Association of Echocardiography. EAE/ASE recommendations for image acquisition and display using three-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25(1):3–46. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorcsan J, 3rd, Tanaka H. Echocardiographic assessment of myocardial strain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(14):1401–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marwick TH, Leano RL, Brown J, Sun JP, Hoffmann R, Lysyansky P, Becker M, Thomas JD. Myocardial strain measurement with 2-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography: definition of normal range. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(1):80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jenkins C, Bricknell K, Hanekom L, Marwick TH. Reproducibility and accuracy of echocardiographic measurements of left ventricular parameters using real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(4):878–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Civelli M, Cardinale D, Martinoni A, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Colombo A, Gandini S, Martinelli G, Fiorentini C, Cipolla CM. Early reduction in left ventricular contractile reserve detected by dobutamine stress echo predicts high-dose chemotherapy-induced cardiac toxicity. Int J Cardiol. 2006;111(1):120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]