Abstract

This study evaluates the ability of a safer sex televised public service announcement (PSA) campaign to increase safer sexual behavior among at-risk young adults. Independent, monthly random samples of 100 individuals were surveyed in each city for 21 months as part of an interrupted-time-series design with a control community. The 3-month high-audience-saturation campaign took place in Lexington, KY, with Knoxville, TN, as a comparison city. Messages were especially designed and selected for the target audience (those above the median on a composite sensation-seeking/impulsive-decision-making scale). Data indicate high campaign exposure among the target audience, with 85%–96% reporting viewing one or more PSAs. Analyses indicate significant 5-month increases in condom use, condom-use self-efficacy, and behavioral intentions among the target group in the campaign city with no changes in the comparison city. The results suggest that a carefully targeted, intensive mass media campaign using televised PSAs can change safer sexual behaviors.

Keywords: mass media campaign, public service announcement, safer sex

HIV prevention intervention research over the past 15 years has begun to show impressive results. A number of studies have shown delay of onset of sexual initiation (e.g., Coyle, Kirby, Marin, Gómez, & Gregorish, 2004), whereas other programs have led to significant increases in condom use in populations including heterosexually active individuals (see Johnson, Carey, Marsh, Levin, & Scott-Sheldon, 2003; Neumann et al., 2002, for reviews). However, most of these interventions have been implemented in small-group (e.g., Belza et al., 2001), school (e.g., Blake et al., 2003; Gallant & Maticka-Tyndale, 2004), or individual-level clinical settings (e.g., Morrison-Beedy & Lewis, 2001). Mass media campaigns, such as televised public service announcement (PSA) campaigns, have recently been shown to be highly effective in changing a variety of behaviors (Hornik, 2002; Noar, 2006), including marijuana use in at-risk adolescents (Palmgreen, Donohew, Lorch, Hoyle, & Stephenson, 2001). For a number of reasons, however, the full potential of these types of media campaigns in the HIV prevention area has not yet been realized (Dejong, Wolf, & Austin, 2001; Myhre & Flora, 2000). In fact, campaigns focused on safer sexual behavior to date have tended to yield modest campaign effects (Snyder & Hamilton, 2002). Thus, we raise the following question: Can a televised PSA campaign based on formative research and sophisticated targeting principles change safer sexual beliefs and behaviors in at-risk young adults? The current study is a rigorous evaluation of a two-city, televised safer sex mass media campaign targeted toward increasing safer sex in young adults who are high sensation seekers and impulsive decision makers.

MASS MEDIA CAMPAIGNS

As noted by Randolph and Viswanath (2004), “Mass media campaigns to promote healthy behaviors and discourage unhealthy behaviors have become a major tool of public health practitioners in their efforts to improve the health of the public” (p. 419). Although the early history of mass media campaigns, particularly those involving health, was largely one of failures (Flay & Sobel, 1983; Rogers & Storey, 1987), the promise of reaching large audiences through the media led to a sharpening of design methodologies, and more realistic campaign expectations. These more sophisticated efforts, combined with more powerful evaluation methodologies, have led to a growing body of research evidence that media health campaigns can be effective when properly designed (Backer, 1990; Hornik, 2002; Noar, 2006; Perloff, 1993; Rogers & Storey, 1987).

Research, generally, has shown that mass media campaigns coupled with other kinds of interventions are more successful than either media or nonmedia efforts alone (Flora, Maibach, & Maccoby, 1989; Rogers & Storey, 1987). There is growing evidence, however, that when used properly media alone can have significant positive impacts on health-related attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (Beck et al., 1990; Derzon & Lipsey, 2002; Flay, 1987; Flora, Maccoby, & Farquhar, 1989; Zastowny, Adams, Black, Lawton, & Wilder, 1993). Large, national media campaigns, conducted in many countries, suggest that mass media campaigns can (1) increase positive attitudes and beliefs about HIV/AIDS (De Vroome, Sandfort, De Vries, Paalman, & Tielman, 1991; Ratzan, Payne, & Massett, 1994; Ross & Rigby, 1990), (2) increase HIV testing in clinics (McOwan, Gilleece, Chislett, & Mandalia, 2002), (3) increase positive beliefs about safer sexual behavior (Agha, 2003), (4) motivate individuals to discuss AIDS information with their friends and family (Chatterjee, 1999) and (5) change safer sex behaviors (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999; Snyder & Hamilton, 2002).

Although effects of media campaigns have been documented, prior safer sex media campaigns have had several weaknesses. First, prior campaigns have been fewer in number and generally less carefully evaluated than those directed at substance use and abuse (e.g., Derzon & Lipsey, 2002; Snyder & Hamilton, 2002). Second, much of the research to date on such campaigns has involved radio (not television), and evaluations have not been rigorously controlled studies (see Myhre & Flora, 2000). Third, most of these studies have exhibited only small effects on behavior (Snyder & Hamilton, 2002). Finally, prior studies that have involved the use of televised PSAs for pregnancy prevention, HIV, and other sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention have suffered from mistakes in campaign execution and lack of targeting (Flay & Sobel, 1983; Lancaster & Lancaster, 2002; Myhre & Flora, 2000).

Current Study

The current study is a rigorous evaluation of a two-city, televised PSA campaign aimed at increasing condom-use beliefs and behaviors in young adults. The study aimed to correct a number of limitations in previous campaign studies by (1) assessing the impact of a televised PSA campaign targeted at increasing condom use in young adults; (2) using audience-segmentation and message-targeting techniques, specifically sensation-seeking targeting (Palmgreen & Donohew, 2003; Palmgreen et al., 2001), to design messages to be persuasive with sensation seekers and impulsive decision makers and to subsequently analyze the data separately for low and high groups; (3) placing the PSAs in programming popular with the target audience; and (4) using an interrupted-time-series (ITS) design with a control community to rigorously evaluate the campaign. These and other principles used in designing the campaign were largely derived from social marketing (e.g., Goldberg, Fishbein, & Middlestadt, 1997).

METHOD

Study Design

The current study involved a 21-month controlled time-series design (Cook & Campbell, 1979). Safer sex PSAs were aired from January 2003 through April 2003 in Lexington, KY, whereas no campaign took place in the comparison city—Knoxville, TN. These two moderate-sized southeastern cities were chosen because of similar demographics. The data examined in the current article were collected between May 2002 and January 2004, a period that includes 8 months prior to the onset of the Lexington campaign (May to December), 3 months during the campaign (January to March), and another 10 months after the campaign (April to January).

Formative Research and PSA Development

The PSAs developed for the campaign were the product of thorough formative research consisting of three waves of focus groups drawn from the target audience. More than 40 sets of focus groups (8–14 individuals per group) were aimed at gaining a better understanding of sexual risk taking as well as pretesting messages with the target audience. Original scripts developed by the research team and ultimately developed into televised PSAs were shown to the target audience to gain feedback. Permission from the Kaiser Family Foundation was secured to use five of its safer sex PSAs (highly rated by focus group participants; see Noar, Palmgreen, Zimmerman, Lustria, & Lu, 2005).

Theoretical Frameworks

Two theoretical frameworks were used to inform the campaign. First, sensation-seeking targeting was utilized in designing campaign messages to be effective in persuading high-sensation-seeking (Noar, Zimmerman, Palmgreen, Lustria, & Horosewski, 2006; Palmgreen et al., 1991, 2001) and impulsive-decision-making (Donohew et al., 2000) young adults to adopt safer sex practices, as well as in dividing the target audience into segments for analysis. Second, a framework of theoretical concepts common to behavioral theories in the health arena was used to guide the content of the messages and subsequent evaluation of the campaign (see Noar, Anderman, Zimmerman, & Cupp, 2004).

The Televised Campaign

The televised safer sex campaign was shown (using a combination of paid and donated time) from January 2003 through early April 2003, in Lexington, KY. The campaign consisted of 10 PSAs that were aired in four flights. A professional media buyer placed the paid PSAs in programming popular with the target audience, as determined by precampaign survey data. Most donated PSAs were placed in the same programs. Standard industry formulas estimated that 75% of the target audience in Lexington would be exposed to the campaign.

Sampling Method and Participants

Beginning 8 months prior to the first campaign, interviews were conducted with independent cross-sectional samples of 100 randomly selected young adults in each community during each month (repeat participants were not allowed). The ages of the population cohort followed in each community, through monthly sampling, were initially between 18 and 23 years, and aged 20 months as we followed the cohort to the end of the study. This was accomplished by continuously adjusting the minimum and maximum ages for eligibility upward by 1 month at the start of each month of interviewing (e.g., from 18 years, 0 months to 23 years, 11 months in Month 1, to a span of 18 years, 1 month to 24 years, 0 months in Month 2).

The self-administered interviews were conducted via laptop computer and were designed to assess a number of variables (see Measures section). Individuals who were called and indicated interest in the survey were screened. To be included in the study, participants had to be (1) in the appropriate age span for the particular study month, (2) heterosexually active (have had sex with an opposite sex partner) in the past 3 months, and (3) a U.S. citizen.

Two sampling methods were combined to recruit participants for the study: random-digit-dial (RDD) methodology and the calling of random samples of registered students at the University of Kentucky (Lexington) and the University of Tennessee (Knoxville). A total of 199,940 different phone numbers were called, most using the much less efficient RDD procedure. Ninety-four percent of the calls did not yield participants (e.g., yielded wrong numbers, individuals who hung up on the interviewer, etc.). Of those who were spoken to (8,315), 60% agreed to complete the brief screener interview. Of those screened and determined to be eligible (4,989), 82% completed interviews for the project, which made a total of 4,032 individuals in the two cities (a small number of individuals were also dropped from analysis after their data were collected because they were not sexually active).

Demographic and sexual descriptors of the samples can be seen in Table 1. In addition, numbers of sexual partners for Lexington men ranged from 1 to 20 (past year) and 1 to 94 (lifetime), with medians of 2 and 7, respectively, and for Lexington women from 1 to 17 (past year) and 1 to 56 (lifetime), with medians of 1 and 5, respectively. For Knoxville men, numbers of partners ranged from 1 to 20 (past year) and 1 to 60 (lifetime), with medians of 2 and 5, respectively, and for Knoxville women from 1 to 21 (past year) and 1 to 50 (lifetime), with medians of 1 and 4, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographics and Sexual Descriptors of the Samples

| Lexington

|

Knoxville

|

Total (N = 4,032)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | M | n | % | M | n | % | M |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 858 | 42.6 | 893 | 44.3 | 1,751 | 43.4 | |||

| Female | 1,158 | 57.4 | 1,123 | 55.7 | 2,281 | 56.6 | |||

| Age (range 18–26 years) | 2,015 | 21.9 | 2,016 | 21.7 | 4,031 | 21.8 | |||

| Race | |||||||||

| White or Caucasian | 1,627 | 80.7 | 1,752 | 86.9 | 3,379 | 83.8 | |||

| Black or African American | 320 | 15.9 | 201 | 10.0 | 521 | 12.9 | |||

| Other/multiracial | 68 | 3.4 | 62 | 3.1 | 130 | 3.2 | |||

| Education completed in years | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | ||||||

| Some high school | 102 | 5.1 | 37 | 1.8 | 139 | 3.4 | |||

| High school degree/GED | 516 | 25.6 | 590 | 29.3 | 1,106 | 27.4 | |||

| Some college | 1,020 | 50.6 | 1,066 | 52.9 | 2,086 | 51.8 | |||

| College degree | 285 | 14.1 | 228 | 11.3 | 513 | 12.7 | |||

| Some graduate school/ graduate degree | 92 | 4.6 | 94 | 4.7 | 186 | 4.6 | |||

| Currently enrolled in college | |||||||||

| Yes | 1,449 | 71.9 | 1,565 | 78.3 | 3,014 | 75.1 | |||

| No | 567 | 28.1 | 433 | 21.7 | 1,000 | 24.9 | |||

| Currently in a relationship | |||||||||

| Yes | 1,452 | 72.0 | 1,477 | 73.3 | 2,929 | 72.7 | |||

| No | 564 | 28.0 | 537 | 26.7 | 1,101 | 27.3 | |||

| Age at first sexual intercourse (years) | 2,016 | 16.4 | 1,984 | 16.7 | 4,000 | 16.6 | |||

| Condom use in past 3 months (range 1 = never to 5 = every time) | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | ||||||

| Never | 628 | 31.2 | 620 | 30.8 | 1,248 | 31.0 | |||

| Sometimes | 841 | 41.8 | 860 | 42.7 | 1,701 | 42.2 | |||

| Every time | 545 | 27.1 | 534 | 26.5 | 1,079 | 26.8 | |||

| Had an STD in past 12 months | |||||||||

| Yes or unsure | 189 | 9.8 | 131 | 6.8 | 320 | 8.3 | |||

| No | 1,742 | 90.2 | 1,789 | 93.2 | 3,531 | 91.7 | |||

| Frequency of intercourse in past 30 days | 10.9 | 11.2 | 11.0 | ||||||

| Male respondents | 731 | 11.6 | 752 | 11.6 | 1,483 | 11.6 | |||

| Female respondents | 1,025 | 10.4 | 965 | 10.9 | 1,990 | 10.6 | |||

NOTE: GED = general equivalency diploma; STD = sexually transmitted disease.

Measures

All multiple-item scales used 5-point Likert-response formats. In addition, items were recoded as necessary, so higher scale scores indicate higher endorsement of variables.

Demographics

Individuals were asked general demographic questions including gender, race/ethnicity, and age.

Sexual Descriptors

Individuals were asked questions including whether they were in an intimate relationship, and how many sexual partners they had had (in the past year and in their lifetime).

Sensation Seeking/Impulsive Decision Making (SSIDM)

A composite risk variable called sensation seeking/impulsive decision making (SSIDM) was created as the product of two scales: sensation seeking and decision making (see Donohew et al., 2000). Sensation seeking was assessed using Hoyle, Stephenson, Palmgreen, Lorch, and Donohew’s (2002) 8-item sexual sensation-seeking scale. Participants were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with items such as “I like to do frightening things.” The scale was reliable, with a coefficient alpha of .74. Next, impulsive decision making was measured with the 12-item decision-making style scale (Donohew et al., 2000). Items included: “I do the first thing that comes into my mind.” Respondents indicated how often these things took place, and this scale was also reliable, with a coefficient alpha of .84. The product of the two mean scores was called SSIDM. Individuals above the median, within Race × Gender categories (to reduce any possible biases in item wording), are referred to hereafter as high sensation seekers/impulsive decision makers (HSSIDMs), and those below the median are referred to as low sensation seekers/rational decision makers (LSSRDMs).

Condom Self-Efficacy

Condom self-efficacy was assessed using the 5-item Confidence in Safer Sex scale (Redding & Rossi, 1999). Respondents indicated how confident they were (from not confident at all to extremely confident) that they could use condoms in situations such as “When you are affected by alcohol or drugs.” Coefficient alpha for the scale was .84.

Condom-Use Intentions

Regarding condom-use intention, respondents were asked how often they planned to use condoms in the next 3 months. Respondents answered this question on a 5-point scale that ranged from never to every time.

Condom Use

Condom use was measured in the current study using one item with a past 3-month time frame (Noar, Cole, & Carlyle, 2006). The item asked the participant how often he or she (or his or her sexual partner) used condoms when having sex. Respondents answered the question on a 5-point scale that ranged from never to every time.

Cued PSA Exposure Measure

Respondents in both cities were shown the five original PSAs developed for the campaign on a laptop computer. After a particular PSA was shown, respondents indicated how often they had seen each PSA by means of five frequency categories (first category = have not seen; last category = more than 10 times). Responses were conservatively recoded to reflect the category median or a low estimate (e.g., more than 10 times was recoded to 11).

Procedure

Individuals who were eligible and indicated interest on the telephone were invited to participate in the survey. They were given various options where they could take the survey, including at their home or at the survey research center. The interviews were private and anonymous. Informed consent was obtained prior to the interview. Next, participants were asked a small number of questions (e.g., demographics) by the interviewer. Then, the majority of the 40–45 min interview was self-administered via a laptop computer. The laptop allowed for greater privacy as well as randomization of the order of items in multiple-item scales. Finally, individuals were paid $30 for their participation (this amount increased by $5 every 6 months as the study progressed). The institutional review boards at both participating universities approved these recruiting and interviewing procedures.

RESULTS

Lexington and Knoxville samples matched closely on most demographic variables, sensation seeking, and on all variables related to condom use (see Table 1), which parallel census and college population figures. However, there were significantly (p <.001) more African Americans in the Lexington sample (corresponding to overall differences in the populations of the two communities), and a significantly higher (p <.001) proportion of respondents in Knoxville were currently enrolled in school. The Lexington sample also had a significantly (p <.001) lower age at first intercourse, higher mean number of sex partners in the past year, and higher mean number of lifetime sex partners, although these differences were very small in magnitude.

Campaign Exposure (Recall)

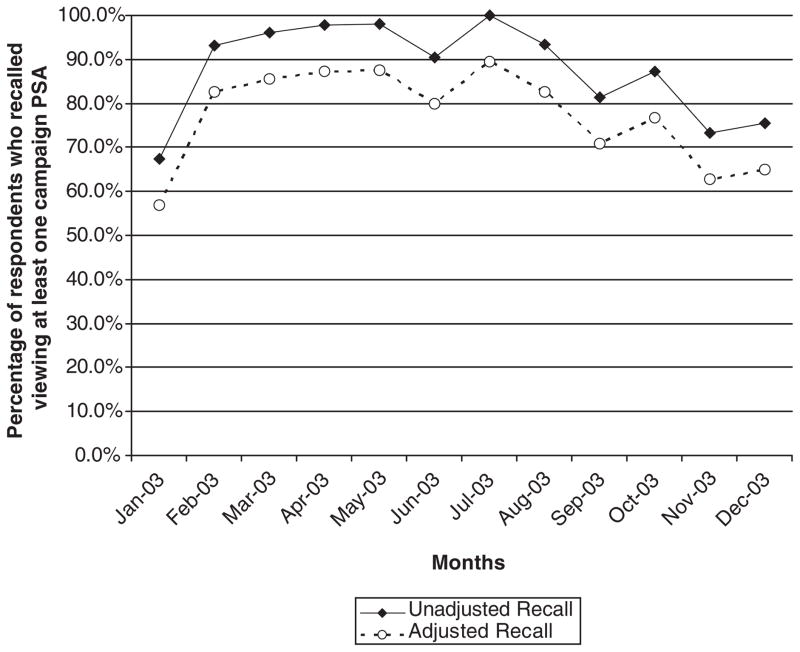

Recall of the campaign PSAs was examined as a self-report measure of exposure. Figure 1 plots campaign recall reported by Lexington respondents from January 2003 (the start of the Lexington campaign) through the end of the study. This figure shows percentages of the target audience (HSSIDMs) who recalled seeing any one of the original campaign PSAs. An analysis of the Knoxville recall data (where no campaign took place) found an average monthly “false positive” recall rate of 10.6%; 10.6% of individuals reported viewing the PSAs when, in actuality, they likely had not. Thus, here we report recall rates unadjusted for this factor as well as adjusted recall (adjusted downward by 10.6% per month) for the Lexington campaign. As expected, recall was lower in the first month (January) of the campaign (67% unadjusted, 56% adjusted recall), and greatly increased to between 93% and 100% (adjusted to 82% and 89%) recall through August. Averaging across the peak months of the campaign (February, March, April), we estimated that 96% (adjusted to 85%) of the target audience recalled seeing at least one of the PSAs.

Figure 1.

Percentage of respondents in Lexington who recalled seeing at least one campaign public service announcement (PSA).

Similar results were found for individuals who recalled seeing two, three, and four or more original campaign PSAs. Here we report mean percentages for each category, in which we averaged recall from the 3 peak months that the campaign aired (February, March, April). Results indicate that 88% recalled seeing two of the PSAs, 75% recalled three PSAs, and 58% recalled four or more of the PSAs. Furthermore, an additional analysis calculated for the same period of time revealed that the target audience, on average, recalled seeing various PSAs 22 times.

Time-Series Regression Analyses

Medians (taking into account race and gender) on the composite SSIDM variable (see Measures section) were used to separate the Lexington and Knoxville monthly samples into groups of high (HSSIDM) and low (LSSRDM) at-risk young adults. Table 2 presents comparisons of these two groups, and demonstrates greater risk for HSSIDMs across a number of sexual risk variables when compared to LSSRDMs. Monthly means for all dependent variables were analyzed with a regression-based ITS procedure appropriate for time-series data sets with fewer than 50 data points (Lewis-Beck, 1986). The procedure employs dummy variables to model slopes, as well as intercept and slope changes as a result of the campaign or wear-out effects. The procedure also tested for autocorrelation. A series of different analyses using various models were run to clarify a complex pattern of results owing to an apparent wear-out effect observed in the campaign city of Lexington.

Table 2.

Comparison of High Sensation Seekers/Impulsive Decision Makers and Low Sensation Seekers/Rational Decision Makers on Risky Sexual Behaviors

| HSSIDM

|

LSSRDM

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | M | n | % | M | t or χ2 Value | df | p Value |

| Age at time of first sexual intercourse (years) | 725 | 16.3 | 721 | 16.6 | −3.37 | 1,444 | .001 | ||

| Sex partners in past year | 719 | 2.9 | 720 | 2.3 | 4.85 | 1,437 | .001 | ||

| Sex partners in lifetime | 716 | 9.0 | 715 | 7.5 | 3.16 | 1,429 | .002 | ||

| Frequency of intercourse in past 30 days | 620 | 10.7 | 618 | 9.8 | 2.24 | 1,236 | .026 | ||

| Had sex with a partner in the last 3 months who had an STD | 24.3 | 1 | .001 | ||||||

| No | 482 | 66.1 | 568 | 77.7 | |||||

| Yes or unsure | 247 | 33.9 | 163 | 22.3 | |||||

| Had sex with a partner in the last 3 months who injected drugs with a needle | 21.80 | 1 | .001 | ||||||

| No | 634 | 87.0 | 688 | 94.1 | |||||

| Yes or unsure | 95 | 13.0 | 43 | 5.9 | |||||

| Had sex with a partner in the last 3 months who was having sex with other people | 40.15 | 1 | .001 | ||||||

| No | 375 | 51.4 | 495 | 67.7 | |||||

| Yes or unsure | 354 | 48.6 | 236 | 32.3 | |||||

| Had sex with a partner in the last 3 months who had sex with both men and women in their past | 14.69 | 1 | .001 | ||||||

| No | 569 | 78.1 | 627 | 85.8 | |||||

| Yes or unsure | 160 | 21.9 | 104 | 14.2 | |||||

NOTE: HSSIDM = high sensation seekers/impulsive decision makers; LSSRDM = low sensation seekers/rational decision makers; STD = sexually transmitted disease.

In addition to presenting these results, the precampaign regression lines in the figures were extrapolated to estimate the trajectory of the Lexington trend in the absence of a campaign in Lexington. Thus, the figures present the actual patterns observed in the presence of a campaign in Lexington as well as an estimate of the expected Lexington secular trend without a campaign (for condom use, condom self-efficacy, and condom-use intentions).

Results for LSSRDMs

As expected, various analyses (including full models run with all possible terms, and reduced models with only initial slope and slope-change terms) involving respondents low on the composite risk variable (SSIDM) showed no significant developmental trends or campaign effects in either city for any of the dependent variables explored, including condom use, condom self-efficacy, and condom-use intentions.

Results for HSSIDMs

For those high on the composite risk variable (HSSIDMs), initial analyses of regression data for all dependent variables were run using five dummy variables: one for the slope prior to the Lexington campaign, slope- and intercept-change variables for the Lexington campaign “interruption,” and slope- and intercept-change variables for the postcampaign slope change for each dependent variable, apparently caused by campaign effects eventually wearing off (as expected). Intercept changes had very high p levels, whereas slope changes (also nonsignificant) had p levels much closer to conventional significance levels. Therefore, following Lewis-Beck (1986), the two nonsignificant intercept-change terms in each of the models run were dropped. This also increased degrees of freedom for estimation—an important improvement, as there were only 21 data points in the time series.

Time Series for Condom Self-Efficacy Among HSSIDMs in Lexington

The time-series regression plot using the reduced model for condom self-efficacy among at-risk young adults in Lexington showed an immediate significant upward trend (p <.05). This was followed by a significant downward trend (p <.05) 3 months after the Lexington campaign ended (see Figure 2). Comparison of the postcampaign trend line with the projected efficacy levels (light-gray line) indicates that, despite a “wear-out” effect, participants had higher self-efficacy, as measured by the 5-point scale (regression estimate = 3.27), at the end of data collection than the level projected in the absence of a campaign (regression estimate = 2.92).

Figure 2.

Lexington and Knoxville condom self-efficacy regression plots for high-sensation-seeking/impulsive-decision-making young adults.

Although the slope changes associated with both the start of the campaign and the wear-out effect were found to be significant (p <.05), the overall reduced model for condom self-efficacy among at-risk young adults was not significant, F(3,17) = 2.53, p = .091, adjusted R2 = .187, with acceptable autocorrelation, ρ= −0.105. This non-significant F value can be explained by the slight downward trend over the first 9 months of the time series, which was not significantly different from zero.

Time Series for Condom-Use Intentions Among HSSIDMs

For condom-use intentions among at-risk young adults in Lexington, the time-series regression model with slope-change terms was significant, F(3,17) = 3.591, p = .036, adjusted R2 = .280, low autocorrelation ρ= −.110. The plot in Figure 3 indicates that the Lexington campaign significantly increased condom-use intentions in those above the median on the composite risk variable, followed by a “wear-out” effect 2 months after the end of the campaign, after which condom-use intentions resumed its precampaign downward trend (see Figure 3). Comparison of the postcampaign trend line with the projected intention levels (light-gray line) indicates that, despite the wear-out effect, participants had higher intentions, as measured by the 5-point scale (regression estimate = 3.10), at the end of data collection than the level projected in the absence of a campaign (regression estimate = 2.81).

Figure 3.

Lexington and Knoxville condom-use-intentions regression plots for high-sensation-seeking/impulsive-decision-making young adults.

Time Series for Condom Use Among HSSIDMs

Time-series regression analyses indicated that the Lexington campaign significantly increased condom use in those above the median on the composite risk variable, followed by the expected “wear-out” effect. Specifically, Lexington analyses indicated the campaign produced a significant immediate upward slope change (p <.05) for condom use in these at-risk young adults that lasted for 3 months after the campaign ended, after which the Lexington sample resumed its precampaign downward trend in condom use (see Figure 4). Comparison of the postcampaign trend line with the projected condom-use levels (light-gray line) indicates that, despite the wear-out effect, participants had higher condom use, as measured by the 5-point scale (regression estimate = 2.60), at the end of data collection than the level projected in the absence of a campaign (regression estimate = 2.32).

Figure 4.

Lexington and Knoxville 3-month condom-use regression plots for high-sensation-seeking/impulsive-decision-making young adults.

Although the slope changes associated with both the start of the campaign and the wear-out effect were found to be significant (p <.05), the overall reduced model for condom use among HSSIDMs was not significant, F(3,17) = 1.99, p = .154, adjusted R2 = .129, with acceptable autocorrelation, ρ= −.222. This nonsignificant F value can be explained by the slight downward trend over the first 9 months of the time series that was not significantly different from zero.

Knoxville Time Series

To test whether the respondents in the comparison no-campaign city exhibited any patterns similar to those in Lexington on the dependent variables, a series of Knoxville time-series analyses, employing the same “interruption” points as Lexington (including full models run with all possible terms, and reduced models with only initial slope and slope-change terms), were calculated. As expected, these analyses showed no significant effects.

Campaign Effect Size and Impact

An effect size for the Lexington condom-use campaign was calculated using Cohen’s d for experimental designs (Carlson & Schmidt, 1999). Pretest condom-use means and standard deviations were calculated by averaging together the precampaign months of October, November, December, and January, and posttest means, by averaging together the postcampaign months of June, July, and August. The means exhibited the pattern of results evident in the figures, with Lexington condom use increasing from pretest (M = 2.8, SD = 1.57) to posttest (M = 3.03, SD = 1.61), whereas Knoxville condom use decreased from pretest (M = 3.14, SD = 1.52) to posttest (M = 2.97, SD = 1.59). Cohen’s d was calculated from these data to be .26, or slightly greater than a “small” effect, as defined by Cohen (1988).

An additional analysis was also calculated to examine campaign impact. Using number of occasions of unprotected intercourse in the past 30 days, estimates derived from regression lines (similar to those in the figures) computed both with and without the impact of the Lexington campaign were compared. On average, HSSIDMs engaged in a total of 10.49 fewer occasions of unprotected intercourse during the 12 months after the campaign began than would have been expected if the precampaign pattern of use (i.e., secular trend) had simply continued. Using 2000 census estimates of the number of 18- to 26-year-olds in Lexington, and dividing by 2 (to yield HSSIDMs), resulted in an estimate of 20,469 individuals. Multiplying by those estimated to be sexually active in a 30-day period (84.4%) yielded 17,276 individuals. Multiplying this figure by the mean number of unprotected intercourse occasions averted as a result of the campaign (10.49) yields an estimate of 181,224 fewer unprotected intercourse occasions among HSSIDMs between January 2003 and December 2003.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the ability of a televised safer sex PSA campaign to change the safer sex beliefs and behaviors of HSSIDM young adults. The results indicated that at the point the PSA campaign began in Lexington, condom use was decreasing in the target audience of HSSIDM young adults in Lexington and fairly constant over time in Knoxville. Lexington young adults’condom use increased just as the campaign was beginning—a significant (p <.05) reversal in trend, apparently in response to the campaign, before the short-term campaign effects began to wear off. Both condom self-efficacy and intentions to use condoms over the subsequent 3 months had nearly identical results to condom use. In addition, no such positive changes took place in the comparison city of Knoxville. Thus, these data suggest that the PSA campaign was effective in increasing the condom-use beliefs and behaviors in HSSIDM young adults in Lexington, and they replicate and extend a similar antimarijuana campaign effort (Palmgreen et al., 2001).

In addition, the results are not only statistically significant (p < .05) but appear to be meaningful from a public health standpoint as well. As discussed, the Lexington campaign appears to have achieved an effect size for condom use of d = .26, slightly above a “small” effect as defined by Cohen (1988). However, when we compare this finding to other safer sex media campaigns, it becomes clear how effective this campaign was in comparison. Snyder and Hamilton (2002) report effect sizes for a number of safer sex campaigns, which range from r = .01 to r = .05. When calculated using the Snyder and Hamilton (2002) method, the current safer sex campaign had an effect size of r = .13. In addition, using Rosenthal’s (1991) binomial effect size display, an r = .13 translates into a 13% increase in “success rate,” which in this case is condom use. This analysis suggests that HSSIDMs increased their condom use, on average, by 13% as a result of the PSA campaign. Further, the additional impact analysis suggested that the campaign may have resulted in a cumulative total of 181,224 fewer unprotected intercourse occasions among HSSIDM individuals than would have taken place without such a campaign.

Although the campaign appears to have been effective, the effects were short-term in nature. This suggests that a continuing campaign presence is necessary to reinforce and sustain a behavior such as condom use, utilizing a constant supply of novel messages to maintain attention. In addition, unlike smoking cessation, in which behavior change is no longer necessary once an individual has quit for good, condom use is a behavior that must consistently be practiced to reduce risk of STDs. In fact, research on stages of change for condom use has found that, similar to smoking behavior, individuals may try numerous times to adopt a new behavior such as condom use before ultimately maintaining the behavior (Evers, Harlow, Redding, & Laforge, 1998). Reinforcement messages that might come in the form of booster campaigns will likely be necessary, especially in light of the fact that young adults increasingly enter into intimate relationships and adopt hormonal birth control methods over condom use (e.g., Noar, Zimmerman, & Atwood, 2004).

Alternatively, it may be unrealistic to expect that media campaigns alone will have the kind of impact needed to sustain behavioral changes over the long term. Thus, combining media campaigns with other behavioral interventions such as school-based programs may be a manner in which to increase the efficacy and ultimate impact and sustainability of intervention efforts. Although some previous studies have done this effectively (e.g., Worden & Flynn, 2002), additional research on synergistic links between health media campaigns and other behavioral interventions is needed.

Overall, the current study adds to the growing literature suggesting that mass media campaigns crafted from sophisticated design principles can be effective in changing health behaviors, at least over the short term (for a review, see Noar, 2006). In fact, with an estimated 85%–96% of the target audience reporting seeing at least one campaign PSA, and an average of 22 exposures per person, the targeting and placement of PSAs appear to have been effective. Previous health campaigns have often had low exposure and recall, with numerous campaigns in the 13% to 17% range and an average of less than 40% exposure (Snyder & Hamilton, 2002). Obviously, PSAs cannot change behavior unless the target audience is reached with those messages. Careful use of targeting principles may achieve the kind of exposure that resulted in the current study (e.g., see Palmgreen & Donohew, 2003).

This study had a number of limitations. Although this research design is robust, particularly for a media campaign study (see Noar, 2006), it is still quasi-experimental and does not eliminate all threats to internal validity. For instance, before the campaign began, condom use was decreasing in Lexington and was essentially flat in Knoxville. This may have indicated that each community was experiencing differential secular trends, making comparisons between the communities more difficult and less conclusive than if the trends had been the same. In addition, although attempts to track “history” events that might have occurred in the communities were made, it is possible that an influencing event (that the researchers were not aware of) took place in one community and not the other. Furthermore, the study was limited to one geographical area of the United States in which a large proportion of individuals are Caucasian. For these reasons, studies replicating and extending these results would increase confidence in the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the measures of condom-use intentions and behavior were single-item measures, which may not be as reliable as multiple-item scales. However, a recent review of the literature suggests that the use of single-item measures for assessing condom use is by far the most widely employed method (Noar, Cole, et al., 2006).

Future studies should continue to build off recent successes with regard to campaign effects on behavior (Hornik, 2002; Noar, 2006), investigating questions such as: (1) Will such a campaign be effective with other populations, such as men who have sex with men? (2) What is the best “dose” of campaign messages and what is the best way to encourage maintenance of behaviors? and (3) How can we achieve even greater impacts on safer sexual behaviors through the use of media campaigns combined with other behavioral interventions? Only further research can aid in increasing the effectiveness of campaign efforts and in having further positive impacts on public health.

Implications for Practitioners

The current study suggests that mass media campaigns alone can be effective in changing sexual risk behavior and related variables if well-documented principles of campaign design are followed. These principles include audience segmentation and targeting, as well as formative research with the target audience. High sensation seekers and impulsive decision makers are particularly useful groups to target because of their proclivity for engaging in risky behaviors. In fact, the characteristics of high-sensation-value messages provide practitioners with useful guidelines for developing effective and persuasive health-related messages and placing them in appropriate channels (see Palmgreen & Donohew, 2003). Also, the extensive formative research utilized here to develop and test campaign messages likely contributed to campaign success. Target audience members can offer invaluable suggestions on ways to increase the persuasive impact of health-related messages.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R01-MH63705 from the National Institute of Mental Health (PI: Rick S. Zimmerman).

References

- Agha S. The impact of a mass media campaign on personal risk perception, perceived self-efficacy and on other behavioural predictors. AIDS Care. 2003;15:749–762. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001618603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer TE. Comparative synthesis of mass media health behavior campaigns. Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion, Utilization. 1990;11:315–329. [Google Scholar]

- Beck EJ, Donegan C, Kenny C, Cohen CS, Moss V, Terry P, et al. An update on HIV-testing at a London sexually transmitted disease clinic: Long-term impact of the AIDS media campaigns. Genitourinary Medicine. 1990;66(3):142–147. doi: 10.1136/sti.66.3.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belza MJ, Llacer A, Mora R, Morales M, Castilla J, dela Fuente L. Sociodemographic characteristics and HIV risk behavior patterns of male sex workers in Madrid, Spain. AIDS Care. 2001;13:677–682. doi: 10.1080/09540120120063296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake SM, Ledsky R, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Lohrmann D, Windsor R. Condom availability programs in Massachusetts high schools: Relationships with condom use and sexual behavior. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:955–962. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson KD, Schmidt FL. Impact of experimental design on effect size: Findings from the research literature on training. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1999;8:851–862. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community-level HIV intervention in five cities: Final outcome data from the CDC AIDS community demonstration projects. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:299–301. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee N. AIDS-related information exposure in the mass media and discussion within social networks among married women in Bombay, India. AIDS Care. 1999;11:443–446. doi: 10.1080/09540129947820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cook T, Campbell D. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle KK, Kirby DB, Marin BV, Gómez CA, Gregorish SE. Draw the line/respect the line: A randomized trial of a middle school intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:843–851. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejong W, Wolf RC, Austin SB. U.S. federally funded television public service announcements (PSAs) to prevent HIV/AIDS: A content analysis. Journal of Health Communication. 2001;6:249–263. doi: 10.1080/108107301752384433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derzon JH, Lipsey MW. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mass-communication for changing substance-use knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. In: Crano WD, Burgoon M, editors. Mass media and drug prevention: Classic and contemporary theories and research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- De Vroome EMM, Sandfort TGM, De Vries KJM, Paalman MEM, Tielman RAP. Evaluation of a safe sex campaign regarding AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases among young people in the Netherlands. Health Education Research. 1991;6:317–325. doi: 10.1093/her/6.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohew L, Zimmerman RS, Cupp PK, Novak S, Colon S, Abell R. Sensation seeking, impulsive decision-making, and risky sex: Implications for risk-taking and design of interventions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;28:1079–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Evers KE, Harlow LL, Redding CA, Laforge RG. Longitudinal changes in stages of change for condom use in women. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1998;13(1):19–25. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-13.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR. Mass media and smoking cessation: A critical review. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:153–160. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Sobel JL. The role of mass media in preventing adolescent substance abuse. In: Glynn TJ, Leukefeld CG, Lundford JP, editors. Preventing adolescent drug abuse: Intervention strategies. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1983. pp. 5–35. NIDA Research Monograph, No. 47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora JA, Maccoby N, Farquhar JW. Communication campaigns to prevent cardiovascular disease: The Stanford community studies. In: Rice RE, Atkins CK, editors. Public communication campaigns. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1989. pp. 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Flora JA, Maibach EW, Maccoby N. The role of media across four levels of health promotion intervention. Annual Review of Public Health. 1989;10:181–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.10.050189.001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant M, Maticka-Tyndale E. School-based HIV prevention programmes for African youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:1337–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg ME, Fishbein M, Middlestadt SE, editors. Social marketing: Theoretical and practical perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik RC, editor. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen PP, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LAJ. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985–2000: A research synthesis. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:381–388. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster AR, Lancaster KM. Reaching insomniacs with television PSAs: Poor placement of important messages. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 2002;3:150–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Beck MS. Interrupted time series. In: Berry WD, Lewis-Beck MS, editors. New tools for social scientists: Advances and application in research methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1986. pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- McOwan A, Gilleece Y, Chislett L, Mandalia S. Can targeted HIV testing campaigns alter health-seeking behaviour. AIDS Care. 2002;14:385–390. doi: 10.1080/09540120220123766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy D, Lewis BP. HIV prevention in single, urban women: Condom-use readiness. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2001;30:148–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhre SL, Flora JA. HIV/AIDS communication campaigns: Progress and prospects. Journal of Health Communication. 2000;5(Suppl):29–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann MS, Johnson WD, Semaan S, Flores SA, Peersman G, Hedges LV, et al. Review and meta-analysis of HIV prevention intervention research for heterosexual adult populations in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;30:S106–S107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM. A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: Where do we go from here? Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(1):21–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730500461059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Anderman EM, Zimmerman RS, Cupp PK. Fostering achievement motivation in health education: Are we applying relevant theory to school-based HIV prevention programs? Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 2004;16(4):59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Cole C, Carlyle K. Condom use measurement in 56 studies of sexual risk behavior: Review and recommendations. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35(3):327–345. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Palmgreen P, Zimmerman RS, Lustria M, Lu HY. What makes an effective public service announcement? 2005. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Zimmerman RS, Atwood KA. Safer sex and sexually transmitted infections from a relationship perspective. In: Harvey JH, Wenzel A, Sprecher S, editors. Handbook of sexuality in close relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 519–544. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Zimmerman RS, Palmgreen P, Lustria MLA, Horosewski ML. Integrating personality and psychosocial theoretical approaches to understanding safer sexual behavior: Implications for message design. Health Communication. 2006;19(2):165–174. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1902_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgreen P, Donohew L. Effective mass media strategies for drug abuse prevention campaigns. In: Slobada Z, Bukoski WJ, editors. Handbook of drug abuse prevention: Theory, science, and practice. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2003. pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Palmgreen P, Donohew L, Lorch EP, Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT. Television campaigns and adolescent marijuana use: Tests of sensation seeking targeting. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:292–296. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgreen P, Donohew L, Lorch E, Rogus M, Helm D, Grant N. Sensation seeking, message sensation value, and drug use as mediators of PSA effectiveness. Health Communication. 1991;3:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Perloff RM. The dynamics of persuasion. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph W, Viswanath K. Lessons learned from public health mass media campaigns: Marketing health in a crowded media world. Annual Review of Public Health. 2004;25:419–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzan SC, Payne JG, Massett HA. Effective health message design: The “America responds to AIDS” campaign. American Behavioral Scientist. 1994;38:294–309. [Google Scholar]

- Redding CA, Rossi JS. Testing a model of situational self-efficacy for safer sex among college students: Stage of change and gender-based differences. Psychology and Health. 1999;14:467–486. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM, Storey JD. Communication campaigns. In: Berger CR, Chaffee SH, editors. Handbook of communication science. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. pp. 817–846. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rigby K. The effect of a national campaign on attitudes towards AIDS. AIDS Care. 1990;2:339–346. doi: 10.1080/09540129008257749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LB, Hamilton MA. A meta-analysis of U.S. health campaign effects on behavior: Emphasize enforcement, exposure, and new information, and beware the secular trend. In: Hornik RC, editor. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Worden JK, Flynn BS. Using mass media to prevent cigarette smoking. In: Hornik RC, editor. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zastowny TR, Adams EH, Black GS, Lawton KB, Wilder AL. Socio-demographic and attitudinal correlates of alcohol and other drug use among children and adolescents: Analysis of a large-scale attitude tracking study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1993;25:223–237. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1993.10472273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]