Abstract

Recently, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as key factors involved in a series of biological processes, ranging from embryogenesis to programmed cell death. Its link to aberrant expression profiles has rendered it a potentially attractive tool for the diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment of various diseases. Accumulating evidence has indicated that miRNAs act as tumor suppressors in hepatocyte malignant transformation by regulating development, differentiation, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. Here, we summarize recent progress in the development of novel biomarker-based miRNA therapeutic strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, MicroRNA, Molecular target, Therapy

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common and rapidly fatal malignancies worldwide. The etiology of HCC is a multi-factorial, multistep, and complex process1 involving chronic and persistent hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and alcohol and aflatoxin B1 intake.2–4 HCC is a highly chemoresistant cancer with no effective systemic or well-established adjuvant therapies, and its prognosis remains poor because of its higher recurrence.5,6 Hepatic resection or transplantation is the only potential curative treatment for HCC patients.7,8

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules that function as endogenous transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression by silencing numerous target genes. Hundreds of miRNAs have been identified in the human genome and tumor tissues. Comprehensive studies of the altered expression of cancer-related miRNAs have allowed for a better understanding of HCC tumor growth, metastatic potential, and recurrence.9–11 Recently, RNA interference (RNAi) has emerged as an innovative gene silencing technology strategy for the treatment of HCC and other tumors.12–14

Extensive studies of miRNA function have uncovered its role in many biological activities, ranging from embryonic development to cell death.15,16 Compelling evidence has revealed that miRNA is an important player in the modulation of diverse cellular processes by targeting coding genes or long non-coding RNAs.17,18 The discovery that more than a 1000 miRNAs are encoded in the human genome further extends our understanding of the complexity of gene regulation. A number of miRNAs are highly conserved across a wide range of distinct species, some with suppressing roles in HCC.19,20 As such, the innovative use of hepatoma-related miRNAs as either biomarkers of disease progression or tumor suppressors therapeutically13,14 is a promising tool for those with HCC. In this review, we summarize the progress of the development of novel biomarker-based miRNA gene therapeutic strategies for HCC.

Targeting hepatoma-related oncogene

The discovery of aberrant miRNA expression profiles in liver cancer largely extended our understanding of HCC, and recent studies have shown that miRNA may be a specific and accurate tool for the clinical diagnosis, prognosis,21–23 and treatment of HCC.24 In order to develop potential therapeutic tools for cancer therapy, researchers utilize viral vector systems to elevate tumor suppressive miRNAs to eliminate carcinogenesis and anti-miRNA oligonucleotides to promote tumorigenesis.25

Of the reported approaches for in vivo miRNA delivery, the adeno- associated viral vector was the most promising for HCC because of the lower risk of vector-related toxicities and higher gene transfer efficacy.26 The level of miR-26a expression is significantly downregulated in the murine model of MYC-induced hepatoma (tet-o-MYC; LAP-tTA mice), which targets cyclin D2 or E2, two influential players in G1/S cell phase. Ectopic expression of miR-26a inhibited cell proliferation and induced tumor cell apoptosis, suggesting that miRNAs with tumor suppressive function may be useful for the treatment of HCC.27,28

In addition to viral vectors, artificially synthesized miRNA or anti-miRNA oligonucleotides may be an efficacious therapeutic strategy for cancer therapy.29 MiR-221 is overexpressed in HCC, and the relative expression of miR-221 in clinical TNM stages III and IV was significantly higher than in stages I and II. The effectiveness of anti-miR-221 oligonucleotides varied depending on the different chemical modification forms. Of the nine forms evaluated, a cholesterol-modified isoform of anti-miR-221 significantly impaired cancer cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo. Transgenic mice that overexpress miR-221 in the liver spontaneously developed liver tumors, and in vivo delivery of antisense 2′-O-methyloligoribo- nucleotide that targeted miR-221 resulted in prolonged survival and significant reduction of the number of tumor nodules. Therefore, use of oligonucleotides may be an effective critical targeted therapy for HCC.30,31

Targeting hepatoma-specific protein

Osteopontin (OPN)

Similarly, restoration of some miRNAs that serve as tumor suppressors could significantly block tumorigenesis and metastasis in vivo. 32 It is well characterized that OPN is overexpressed in liver cancer patients with enhanced metastasis and poor prognosis, and repression of OPN using a neutralizing antibody significantly weakened cell migration and invasiveness in vitro. The artificial miRNAs, designated for targeting OPN, significantly inhibited OPN expression in the HCCLM3 cell line and resulted in decreased in vivo tumor growth and lung metastasis through the repression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathways.33,34

Glypican-3 (GPC -3)

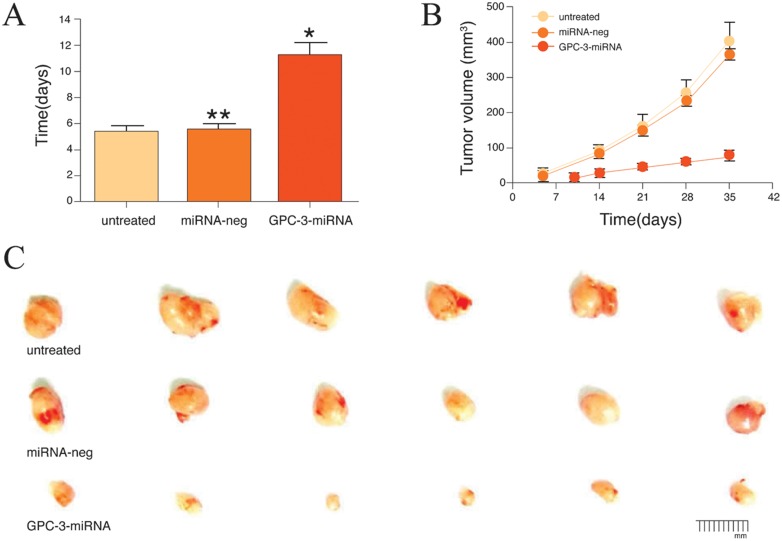

GPC-3 is a membrane anchored heparin sulfate proteoglycan expressed in fetal liver and placenta but not in normal adult liver tissue. It is specifically overexpressed in hepatoma.35–37 Silencing the expression of GPC-3 with transfected miRNA was shown to decrease HepG2-linked cell proliferation and inhibit HepG2 mRNA and protein levels. Proliferation was inhibited by 71.1% in the miRNA group and 79.5% in the miRNA plus sorafenib (100 μM/L) group. Transfected cells were arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, and apoptosis rate was increased from 42.2% in the neg-miRNA group to 65.6 % in the miRNA group. As shown in Fig. 1, miRNA specific for GPC-3 might inhibit HCC cell proliferation by cell apoptosis in vitro. 38 GPC-3 miRNA mediated downregulation of GPC-3 expression was shown to inhibit xenograft tumor growth in naked mice through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in vivo. Taken together, these findings identify GPC-3 gene as a potential molecular target for HCC gene therapy.

Fig. 1. Silencing GPC-3 inhibited the growth of nude mice xenograft tumors.

(A) Formation times of xenograft tumors in nude mice after injection with stable HepG2 cells with miRNA plasmids; (B) Comparative analysis of nude mice xenograft tumor volumes in different groups, data are expressed as mean ±SD (n=6); (C) Dissected hepatoma xenograft tumors in the different groups (unpublished findings, Yao et al.).

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)

To date, circulating AFP is the most commonly used biomarker to screen for HCC.39 There are two subtypes for prognostic prediction: EpCAM+AFP+ HCC (hepatoma stem cell (HSC)-HCC) with enhanced metastatic properties and poor outcome and EpCAM−AFP−HCC (mature hepatocyte-like HCC; MH-HCC) with good prognosis. Detection of EpCAM and AFP expression status are performed in conjunction with transcriptome analysis in HCC specimens.40 When comparing miRNA expression profiles between the two groups, the specific miRNAs preferentially expressed in HSC-HCC and the highly conserved miR-181 families are highly expressed in EpCAM+ AFP+ cells isolated from AFP+ HCC specimens.41–43

It was determined experimentally that the miR-181 family members target Caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2, GATA binding protein 6, and Nemo-like kinase, proteins essential for cell differentiation and the Wnt signaling pathway. The sophisticated molecular alternation in hepatocarcinogenesis provides a long-lasting challenge for researchers, and EpCAM+AFP+HCC patients might be potential therapeutic candidates for anti-angiogenesis therapy.44 Although encouraging progress has been achieved regarding the elucidation of the molecular mechanism of miRNA and HSCs, future studies are needed to further determine how miRNAs are involved in HSC development and tumor progression.

Downregulating expression of key molecules in HCC-related pathways

Several signaling pathways have been unraveled in the study of hepatocarcinogenesis, including PIK3C2α/Akt/HIF-1α, NF-κB, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II/IGF-IR, met, myc, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, hedgehog, p53, Wnt/β-catenin, and epidermal growth factor (EGF). Many of these pathways overlap with pathways associated with hepatic progenitor cells.45,46 MiRNA and other non-coding RNAs have been reported in HSCs. Based on computational and experimental evidence, it has been estimated that miRNAs encoded by the genome could modulate approximately 60% of mammalian genes, highlighting the importance of miRNAs in the orchestration of gene expression.22 Furthermore, a single miRNA may affect the expression levels of multiple target genes. Therefore, it will not be surprising that a single miRNA would act in both normal into cancer cells16 to functionally regulate carcinogenesis.47

Wnt/β-Catenin pathway

Abnormal expressions of some key molecules in the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway were associated with the occurrence and development of HCC. The Wnt proteins are secreted glycoproteins that bind to the N-terminal extracellular cysteine-rich domain of the Frizzled (Fzd) receptor family. Activation of Fzd receptors by Wnt activates canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways.48 The Fzd7, a member of the Fzd family, is commonly upregulated in a variety of cancers, including HCC and triple negative breast cancer and plays an important role in stem cell biology and hepatoma progression. Inhibition of Fzd7 with siRNA knockdown, anti-Fzd7 antibodies, or the extracellular peptide of Fzd7 (soluble Fzd7 peptide) promoted anti-cancer activity in vitro and in vivo mainly by inhibiting the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.49 In addition, pharmacological inhibition of Fzd7 by small interfering peptides or a small molecule inhibitor suppressed β-catenin-dependent tumor cell growth. Therefore, targeted inhibition of Fzd7 represents a rational and promising new approach for cancer therapy.

IGF-II/IGF-IR pathway

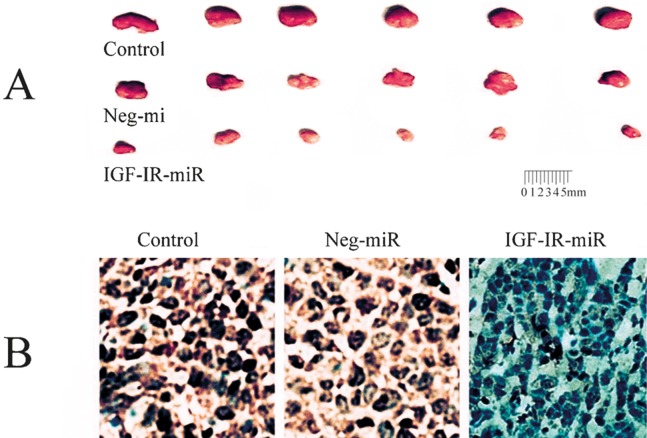

IGF-II is a mitogenic polypeptide closely linked to the complex regulation of transcription, and its expression results in generation of multiple mRNAs initiated by different promoters.50,51 Because both IGF-II and IGF-I receptors are highly overexpressed in hepatocarcinogenesis, IGF-II is suspected to serve as an autocrine growth factor.52,53 Downregulation of IGF-II expression by specific miRNAs resulted in viability alteration, proliferation inhibition, and apoptosis in HepG2 cells. The level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the supernatant of HepG2 cells in the miRNA-IGF-II transfected group was significantly less and the susceptibility to anoikis and anchorage-independent colony formation decreased than those in the untransfected or the miRNA-neg transfected group.54 In hepatoma cells transfected with IGF-IR-miRNA, cell cycle progression was inhibited through G0/G1 arrest in Bel-7404 and PLC/PRF/5 cells, cell proliferation was inhibited with apoptosis, and the expression of cyclinD1 was significantly inhibited in vitro. In addition, the growth of xenograft tumors was significantly inhibited in vivo (Fig. 2). Taken together, these findings suggest that IGF-II or IGF-IR is a potential molecular target for HCC gene therapy.

Fig. 2. Alterations of histopathology and immunohistochemistry in xenograft tumors.

(A) The size and gross features of xenograft tumors in nude mice from the different treatment groups: control group, PLC/PRF/5 cells transfected without any miR; the neg-miR group, PLC/PRF/5 cells transfected with neg-miR; the miR group, PLC/PRF/5 cells transfected with miR; (B) IGF-IR IGF-IR immunohistochemical analysis of the xenograft tumor tissues (SP, 400 ×) (unpublished data, Yao et al.).

NF-κB pathway

Chronic infection with HBV or HCV is involved in the development and progression of HCC. Hepatitis virus with tumorigenic protein (HBx or core protein of HCV) can activate a variety of signaling pathways, including NF-κB, that modulate the expression of many genes linked with HCC. The effects of siRNA-mediated inhibition of NF-κB on cell growth were investigated in hepatoma cells. Prior to transfection, the expression of NF-κB/p65 mRNA was significantly higher in HepG2 cells than that in LO2 cells, whereas the expression levels of NF-κB/p65 mRNA and protein in HepG2 cells were significantly reduced in p65 siRNA transfected cells. Interestingly, the apoptosis index was increased up to 85% in HepG2 cells and overexpression of NF-κB in hepatoma cells can be inhibited by p65 siRNA via an apoptotic mechanism, suggesting that NF-κB may be a viable molecular-target for HCC gene therapy.53

Therapeutic miRNAs and effects on HCC drug-resistance

Aberrantly expressed miRNAs have been identified in HCC drug-resistance mechanisms. HCC tissues are organized in a hierarchy consisting of heterogeneous cell populations, and the capability to maintain tumorigenesis exclusively relies on a small population of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).55 The aforementioned new findings largely extend our understanding of the regulation of HSCs and shed light on the development of novel therapeutic strategies to fight against chemotherapy-resistant HCC. MiRNA-based therapies that specifically target HSCs may provide novel firepower in the war against HCC. Tumor-initiating stem-like cells (TISCs) not only are resistant to chemotherapy and but are also associated with metastatic HCC. Tlr4 expression is higher in HCC relative to CD133−/CD49f+ cells. ITlr4 may be a universal proto-oncogene responsible for the genesis of TLR4-NANOG dependent TISCs, making it a novel potential therapeutic target for HCC.56

A moderate expression of miR-21 in HCC tissues was associated with a favorable response to the IFN-α/5-fluoro-2, 4(1h, 3h) pyrimidinedione (5-FU) combination therapy and a better survival prognosis. Hepatoma cells with elevated expression of miR-21 exhibited lower drug sensitivity to the cellular cytotoxicity induced by IFN-α in conjunction with 5-FU, and a high level of miR-21 in HCC biopsies indicated an unfavorable response to the IFN-α/5-FU combination chemotherapy. In HCC where HepG2 cells sensitized to apoptosis induced by serum starvation or chemotherapeutic drugs through targeting myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 gene, a well-characterized anti-apoptotic member of Bcl-2 family, miR-101 was frequently downregulated. These novel findings suggest that HCC patients may benefit from specific miRNA adjuvant administration based on diverse miRNA expression profiles in different individuals suffering from HCC.56,57

Conclusions

Increasing evidence has highlighted the importance of miRNAs in the control of HCC suppressors, growth, invasiveness, and curability (Table 1). The management of advanced HCC is entering a new era of molecular targeting therapy, which is of particular significance for HCC because of the lack of effective systemic therapies for HCC. The transcription and activation of specific vector mediated RNAi has been successfully used to suppress hepatoma cells via viability alteration, proliferation inhibition, and promotion of apoptosis. However, technical difficulties, including stability and the bioavailability and safety of miRNAs-based therapeutics, have restricted the development of miRNA clinically. Despite the inspiring progress in miRNA-mediated gene activation techniques and insight into the mechanisms of tumorigenesis, many questions remain and a new perspective regarding the development of new curative approaches is required. In general, the use of miRNAs is a promising area for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for HCC.58,59

Table 1. Summary of several related-microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma and their biological roles.

| miRs | Targets | Biological roles | References |

| miR-AFP | AFP, beclin-1 | Proliferation, apoptosis | Peng FL, et al. (2013) |

| miR-HIF-1α | HIF-1α | Angiogenesis, proliferation | Wang L, et al. (2013) |

| miR-GPC-3 | GPC-3, Wnt/β- catenin | Angiogenesis, metastasis, proliferation | Chen J, et al. (2013) |

| miR-1 | ET1 | Proliferation | Li D, et al. (2012) |

| miRs-7 | Caspase-3, HMGA2, C-myc, Bcl-xl | Proliferation, apoptosis | Ji J, et al. (2010) |

| miR-IGF-II | IGF-II/IGF-IR pathway | Proliferation, angiogenesis, apoptosis | Yao NH, et al. (2012) |

| miR-101 | Mcl-1, SOX-9, EZH2, EED, DNMT3A | Proliferation, apoptosis | Tsai WC, et al. (2009) |

| miRs-122 | Bcl-w, ADAM-1, Wnt-1 | Angiogenesis, apoptosis, metastasis | Xu J , et al. (2012) |

| miR-125a, -125b | MMP11, SIRT7, VEGF-A, LIN28B2, Bcl | Angiogenesis, metastasis, proliferation | Kim JK, et al. (2013) |

| miR-139 | c-Fos, Rho-kinase-2 | Metastasis | Wong CC, et al. (2011) |

| miR-145 | IRS1-2, OCT4, IGF pathway | Stem-like cells tumorigenicity | Jia Y, et al. (2012) |

| miR-195 | CDK6, E2F3, cyclinD1 | Proliferation, apoptosis, tumorigenicity | Yang X, et al. (2012) |

| miR-199a-3p, -199-5p | c-Met, mTOR, PAK4, DDR1, caveolin-2 | Proliferation, autophagy, metastasis | Huh J, et al. (2011) |

| miRs-214 | HDGF, β-catenin | Proliferation, angiogenesis, metastasis | Xia H, et al. (2012) |

| miR-10a | EphA4, CADM1 | EMT metastasis | Li QJ, et al. (2012) |

| miR-21 | Pten, RhoB, PDCD4 | Drug Resistance, metastasis | Meng F, et al. (2007) |

| miR-221 | Bmf, DDIT4, Arnt, CDKN1B/p27 or1C/p57 | Angiogenesis, apoptosis, proliferation | Yuan Q, et al. (2013) |

| miRs-224 | Yin Yang1/Raf-1 kinase, NF-kB, apoptosis inhibitor-5 | Proliferation, apoptosis, metastasis | Wang Y, et al. (2008) |

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (81200634), the Projects of Jiangsu Medical Science (2013-WSW-011, HK201102, BL2012053) & the Qinglan Project of higher education (12KJB310013), and the International S & T Cooperation Program (2013DFA32150) of China. We thank T. FitzGibbon, M.D., for helpful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 5-FU

5-fluoro-2, 4(1h, 3h) pyrimidinedione

- AFP

alpha-fetoprotein

- Fzd

frizzled

- GPC-3

glypican-3

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HSCs

hepatoma stem cells

- IGF

insulin- like growth factor

- IGF-IR

insulin-like growth factor-I receptor

- IFN

interferon

- miRNA

microRNA

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- OPN

osteopontin

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TISCs

tumor-initiating stem-like cells

- miRs

microRNAs

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Li J, Shi W, Gao Y, Yang B, Jing X, Shan S, et al. Analysis of microRNA expression profiles in human hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Lab. 2013;59:1009–1015. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2012.120901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–1273. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang YH, Wen TF, Chen X. Resection margin in hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1393–1397. doi: 10.5754/hge10600. 10.5754/hge10600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taziel M, Essadi I, M'rabti H, Touyar A, Errihani PH. Systemic treatment and targeted therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:167–175. doi: 10.4297/najms.2011.3167. 10.4297/najms.2011.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao H, Phan H, Yang LX, Touyar A, Errihani PH. Improved chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1379–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melloul E, Lesurtel M, Carr BI, Clavien PA. Developments in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:510–521. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.05.008. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen YC, Hsu C, Cheng CC, Hu FC, Cheng AL. A critical evaluation of the preventive effect of antiviral therapy on the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C or B: a novel approach by using meta-regression. Oncology. 2012;82:275–289. doi: 10.1159/000337293. 10.1159/000337293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finn RS, Zhu AX. Targeting angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: focus on VEGF and bevacizumab. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:503–509. doi: 10.1586/era.09.6. 10.1586/era.09.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broderick JA, Zamore PD. MicroRNA therapeutics. Gene therapy. 2011;18:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.50. 10.1038/gt.2011.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu C, Lee SA, Chen X. RNA interference as therapeutics for hepatocellular carcinoma. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2011;6:106–115. doi: 10.2174/157489211793980097. 10.2174/157489211793980097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gailhouste L, Ochiya T. Cancer-related microRNAs and their role as tumor suppressors and oncogenes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2013;28:437–451. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger F, Reiser MF. Micro-RNAs as potential new molecular biomarkers in oncology: have they reached relevance for the clinical imaging sciences? Theranostics. 2013;3:943–952. doi: 10.7150/thno.7445. 10.7150/thno.7445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaiteerakij R, Addissie BD, Roberts LR. Update on biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Nov 23; doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.10.038. 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bader AG, Brown D, Stoudemire J, Lammers P. Developing therapeutic microRNAs for cancer. Gene Therapy. 2011;18:1121–1126. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.79. 10.1038/gt.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi W, Liang W, Jiang H, Miuyee Waye M. The function of miRNA in hepatic cancer stem cell. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:358902. doi: 10.1155/2013/358902. 10.1155/2013/358902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elhefnawi M, Soliman B, Abu-Shahba N, Amer M. An integrative meta-analysis of microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2013;11:354–367. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2013.05.007. 10.1016/j.gpb.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekar TV, Mohanram RK, Foygel K, Paulmurugan R. Therapeutic evaluation of microRNAs by molecular imaging. Theranostics. 2013;3:964–985. doi: 10.7150/thno.4928. 10.7150/thno.4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YJ, Thang MW, Chan YT, Huang YF, Ma N, Yu AL, et al. Global assessment of antrodia cinnamomea-induced microRNA alterations in hepatocarcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082751. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivasan S, Selvan ST, Archunan G, Gulyas B, Padmanabhan P. MicroRNAs-the next generation therapeutic targets in human diseases. Theranostics. 2013;3:930–942. doi: 10.7150/thno.7026. 10.7150/thno.7026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong ZZ, Yao M, Wang L, Gu X, Shi Y, Qiu LW, et al. Epigenetic alterations of hepatic IGF-II gene promoter and IGF-II abnormal expression in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2013;6:177–187. 10.13005/bpj/401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou W, Bonkovsky HL. Non-coding RNAs in hepatitis C-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: Dysregulation and implications for early detection, diagnosis and therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7836–7845. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.7836. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.7836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z, Ma T, Huang C, Zhang L, Xu T, Hu T, et al. MicroRNA-148a: a potential therapeutic target for cancer. Gene. 2014;533:456–457. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.067. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan H, Wang S, Yu H, Zhu J, Chen C. Molecular pathways and functional analysis of miRNA expression associated with paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Pharmacology. 2013;92:167–174. doi: 10.1159/000354585. 10.1159/000354585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ronald JA, Katzenberg R, Nielsen CH, Jae HJ, Hofmann LV, Gambhir SS. MicroRNA-regulated non-viral vectors with improved tumor specificity in an orthotopic rat model of hepato- cellular carcinoma. Gene Ther. 2013;20:1006–1013. doi: 10.1038/gt.2013.24. 10.1038/gt.2013.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, Liang L, Zhang XF, Jia HL, Qin Y, Zhu XC, et al. MicroRNA-26a suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of human hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting interleukin-6-Stat3 pathway. Hepatology. 2013;58:158–170. doi: 10.1002/hep.26305. 10.1002/hep.26305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Zheng J, Zhang Y, Yang L, Wang J, Ni J, et al. Tumor-specific expression of microRNA-26a suppresses human hepatocellular carcinoma growth via cyclin-dependent and -independent pathways. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1521–1528. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.64. 10.1038/mt.2011.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang X, Jia Z. Construction of HCC-targeting artificial miRNAs using natural miRNA precursors. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:209–215. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1111. 10.3892/etm.2013.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rong M, Chen G, Dang Y. Increased miR-221 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues and its role in enhancing cell growth and inhibiting apoptosis in vitro. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-21. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park JK, Kogure T, Nuovo GJ, Jiang J, He L, Kim JH, et al. miR-221 silencing blocks hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes survival. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7608–7616. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1144. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu B, Wen X, Huang C, Jiang J, He L, Kim JH, et al. Unraveling the complexity of hepatitis B virus: from molecular understanding to therapeutic strategy in 50 years. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:1987–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.017. 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen RX, Xia YH, Xue TC, Ye SL. Suppression of microRNA-96 expression inhibits the invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:800–804. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.695. 10.3892/mmr.2011.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharya SD, Garrison J, Guo H, Mi Z, Markovic J, Kim VM, et al. Micro-RNA-181a regulates osteopontin-dependent metastatic function in hepatocellular cancer cell lines. Surgery. 2010;148:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.05.007. 10.1016/j.surg.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao M, Yao DF, Bian YZ, Wu W, Yan XD, Yu DD, et al. Values of circulating GPC-3 mRNA and alpha- fetoprotein in detecting patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(13)60028-4. 10.1016/S1499-3872(13)60028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao M, Yao DF, Bian YZ, Zhang CG, Qiu LW, Wu W, et al. Oncofetal antigen glypican-3 as a promising early diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60048-9. 10.1016/S1499-3872(11)60048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu D, Dong Z, Yao M, Wu W, Yan M, Yan X, et al. Targeted glypican-3 gene transcription inhibited the proliferation of human hepatoma cells by specific short hairpin RNA. Tumor Biol. 2013;34:661–668. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0593-y. 10.1007/s13277-012-0593-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu DD, Yao M, Chen J, Wang L, Yan MJ, Gu X, et al. Short hairpin RNA mediated glypican-3 silencing inhibits hepatoma cell invasiveness and disrupts molecular pathways of angiogenesis. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2013;21:452–458. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2013.06.016. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao DF, Dong ZZ, Yao M. Specific molecular markers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terris B, Cavard C, Perret C. EpCAM, a new marker for cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2010;52:280–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.026. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ji J, Yamashita T, Budhu A, Forgues M, Jia HL, Li C, et al. Identification of microRNA-181 by genome- wide screening as a critical player in EpCAM-positive hepatic cancer stem cells. Hepatology. 2009;50:472–480. doi: 10.1002/hep.22989. 10.1002/hep.22989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shan YF, Huang YL, Xie YK, Tan YH, Chen BC, Zhou MT, et al. Angiogenesis and clinicopathologic characteristics in different hepatocellular carcinoma subtypes defined by EpCAM and α-fetoprotein expression status. Med Oncol. 2011;28:1012–1016. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9600-6. 10.1007/s12032-010-9600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J, Ruan B, You N, Huang Q, Liu W, Dang Z, et al. Downregulation of miR-200a induces EMT phenotypes and CSC-like signatures through targeting the β-catenin pathway in hepatic oval cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079409. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chai ZT, Kong J, Zhu XD, Zhang YY, Lu L, Zhou JM, et al. MicroRNA-26a inhibits angiogenesis by down- regulating VEGFA through the PIK3C2α/Akt/HIF-1α pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077957. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong ZZ, Yao M, Wang L, Wu W, Gu X, Yao DF. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha: molecular -targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2013;13:1295–1304. doi: 10.2174/1389557511313090004. 10.2174/1389557511313090004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun X, He Y, Huang C, Ma TT, Li J. Distinctive microRNA signature associated of neoplasms with the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cell Signal. 2013;25:2805–2811. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.09.006. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong Z, Yao M, Zhang H, Wang L, Huang H, Yan M, et al. Inhibition of Annexin A2 gene transcription is a promising molecular target for hepatoma cell proliferation and metastasis. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:28–34. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1663. 10.3892/ol.2013.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin X, Li YW, Jin JJ, Zhou Y, Ren ZG, Qiu SJ, et al. The clinical and prognostic implications of pluripotent stem cell gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1155–1162. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1151. 10.3892/ol.2013.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang Y, Feng Y, Wu T, Srinivas S, Yang W, Fan J, et al. Aflatoxin B1 negatively regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway through activating miR-33a. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073004. 10.1371/journal.pone.0073004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King TD, Zhang W, Suto MJ, Li Y. Frizzled7 as an emerging target for cancer therapy. Cell Signal. 2012;24:846–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.12.009. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan XD, Yao M, Wang L, Zhang HJ, Yan MJ, Gu X, et al. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor as a pertinent biomarker for hepatocytes malignant transformation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6084–6092. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i36.6084. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i36.6084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dong ZZ, Yao M, Wang L, Yan X, Gu X, Shi Y, et al. Abnormal expression of insulin-like growth factor-I receptor in hepatoma tissue and its inhibition to promote apoptosis of tumor cells. Tumor Biol. 2013;34:3397–3405. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0912-y. 10.1007/s13277-013-0912-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao NH, Yao DF, Wang L, Dong Z, Wu W, Qiu L, et al. Specific miRNA inhibited IGF-II activation on effect of human HepG2 cell proliferation and angiogenesis factor expression. Tumor Biol. 2012;33:1767–1776. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0436-x. 10.1007/s13277-012-0436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu W, Yao DF, Wang YL, Qiu L, Sai W, Yang J, et al. Suppression of human hepatoma (HepG2) cell growth by nuclear factor-kappaB/p65 specific siRNA. Tumor Biol. 2010;31:605–611. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0076-y. 10.1007/s13277-010-0076-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu G, Jing Y, Kou X, Ye F, Gao L, Fan Q, et al. Hepatic stellate cells secreted hepatocyte growth factor contributes to the chemoresistance of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073312. 10.1371/journal.pone.0073312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen CL, Tsukamoto H, Liu JC, Kashiwabara C, Feldman D, Sher L, et al. Reciprocal regulation by TLR4 and TGF-β in tumor-initiating stem-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2832–2849. doi: 10.1172/JCI65859. 10.1172/JCI65859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Tomimaru Y, Eguchi H, Nagano H, Wada H, Tomokuni A, Kobayashi S, et al. MicroRNA-21 induces resistance to the anti-tumour effect of interferon-α/5-fluorouracil in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1617–1626. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605958. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu Z, Zhang C, Cui J, Song Q, Wang L, Kang J, et al. Bioinformatic analysis of the membrane cofactor protein CD46 and microRNA expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:557–564. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2877. 10.3892/or.2013.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen J, Wang S, Zhang YJ, Kappil MA, Chen Wu H, Kibriya MG, et al. Genome-wide aberrant DNA methylation of microRNA host genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Epigenetics. 2012;7:1230–1237. doi: 10.4161/epi.22140. 10.4161/epi.22140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saito Y, Hibino S, Saito H. Alterations of epigenetics and microRNA in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:31–44. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12147. 10.1111/hepr.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]