Abstract

Introduction

Pressure ulcers are a common and severe complication of spinal cord injury, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries where people often need to manage pressure ulcers alone and at home. Telephone-based support may help people in these situations to manage their pressure ulcers. The aim of this study is to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telephone-based support to help people with spinal cord injury manage pressure ulcers at home in India and Bangladesh.

Methods and analysis

A multicentre (3 sites), prospective, assessor-blinded, parallel, randomised controlled trial will be undertaken. 120 participants with pressure ulcers on the sacrum, ischial tuberosity or greater trochanter of the femur secondary to spinal cord injury will be randomly assigned to a Control or Intervention group. Participants in the Control group will receive usual community care. That is, they will manage their pressure ulcers on their own at home but will be free to access whatever healthcare support they can. Participants in the Intervention group will also manage their pressure ulcers at home and will also be free to access whatever healthcare support they can, but in addition they will receive weekly telephone-based support and advice for 12 weeks (15–25 min/week). The primary outcome is the size of the pressure ulcer at 12 weeks. 13 secondary outcomes will be measured reflecting other aspects of pressure ulcer resolution, depression, quality of life, participation and satisfaction with healthcare provision. An economic evaluation will be run in parallel and will include a cost-effectiveness and a cost-utility analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee at each site. The results of this study will be disseminated through publications and presented at national and international conferences.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12613001225707.

Keywords: Telemedicine < BIOTECHNOLOGY & BIOINFORMATICS, WOUND MANAGEMENT, HEALTH ECONOMICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This randomised controlled trial will examine a potentially simple and inexpensive approach to the management of pressure ulcers secondary to spinal cord injury (SCI) in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC).

This will be one of the first and largest non-pharmacological studies of this type involving people with SCI from LMIC.

This is a multicentre study increasing the study's external validity.

Assessors will be blinded, but it is not possible to blind participants or the clinicians.

Introduction

Pressure ulcers are a common and severe complication of spinal cord injury (SCI).1 2 They have many deleterious consequences, including permanent scarring, osteomyelitis, amputation and sepsis, often requiring hospital admissions.3 4 In addition, they affect a person's family and social life, and are costly and difficult to manage. Pressure ulcers can also lead to death. It is estimated that pressure ulcers are responsible for approximately 8% of deaths in people with SCI in high-income countries.5 This figure is probably much higher in low-income and middle-income countries (LMIC). One small study from Nepal6 found that 25% of patients from a local SCI hospital had pressure ulcers within a year of discharge. A larger study from Bangladesh7 reported that 70% of people with paraplegia and 90% of people with tetraplegia were dead within 5 years of injury, most from pressure ulcers. While there are methodological limitations with these studies, there is general consensus that pressure ulcers are a major and life-threatening problem.8 Pressure ulcers can not only adversely affect quality of life, depression, anxiety and other psychological disorders but can also limit a person's ability to participate in meaningful community activities.

Pressure ulcers are most common around the sacrum, ischial tuberosity and greater trochanter of the femur.9 They progress through different stages of severity if left untreated. They are scored from stage 1 to stage 4.9 10 Stage 4 pressure ulcers are severe and invariably require hospitalisation and surgery. Stage 1–stage 3 pressure ulcers vary from superficial red areas to full skin thickness injuries. In high-income countries, pressure ulcers are either managed with hospitalisation or regular home nursing, and pressure relieving devices such as alternating pressure air mattresses. However, these levels of service and resources are often not available in LMIC because hospitals and community healthcare services are under-resourced and most people cannot afford to self-fund these services or access costly equipment.11 Instead, usual care in these countries typically involves people managing their pressure ulcers alone and at home. Often, they become life-threatening. However, with early advice, most people can be taught self-help strategies to manage less severe pressure ulcers at home.12 This includes education about appropriate pressure relief, bed overlays, diet and wound dressings. It also includes education about bladder and bowel management to minimise incontinence that often contributes to further deterioration of pressure ulcers.13

Telephone-based support may provide a low cost way of helping people with SCI manage pressure ulcers at home in LMIC.14 This is a feasible way to provide support because mobile phones15 are popular in most LMIC. A small number of studies have looked at the possible use of telephone-based support for the treatment of pressure ulcers.16 17 However, these studies have only had small numbers of participants and were conducted in high-income countries. There is presently no strong evidence indicating that telephone-based support is effective for the treatment of pressure ulcers, especially in LMIC such as India and Bangladesh.

Aim

The aim of this study is to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telephone-based support for people with pressure ulcers secondary to SCI in LMIC. A randomised controlled trial will be conducted in India and Bangladesh. It will be the first prospective study to investigate this question.

Methods and analysis

Design

A multicentre, prospective, assessor-blinded, parallel, pragmatic randomised controlled trial will be undertaken, in which people with pressure ulcers secondary to SCI will be randomised to usual community care or to usual community care plus telephone-based support over 12 weeks.

Participants

Participants will be included if they:

Are over 18 years of age;

Have sustained complete or incomplete SCI more than 3 months prior to recruitment;

Have at least one pressure ulcer on the sacrum, ischial tuberosity or greater trochanter of the femur which is unlikely to require hospitalisation within the next 12 weeks;

Are living in the community;

Are able to speak either sufficient Hindi (for the 2 Indian sites) or Bengali (for the Bangladesh site) to allow them to participate in the study without the assistance of a translator;

Have access to a phone and will be able to comply with regular phone interviews as specified by the protocol;

Have the potential to benefit from the telephone-based support.

Participants will be excluded if they:

Have cognitive or verbal impairments;

Have any clinically significant medical condition that would compromise participation in the study;

Are unable to be assessed at 12 weeks.

Potential participants will be recruited from outpatient clinics or the hospitals’ databases.

Recruitment strategy and time frame

A study researcher will contact potential participants in person during outpatient clinics or via telephone (using the hospitals’ databases to identify people). Those recruited through outpatient clinics will be provided with a participant information sheet and screened for inclusion. Those recruited via telephone will be invited to participate. At a subsequent appointment, they will be provided with a participant information sheet and screened for inclusion.

Participant recruitment started on 25 November 2013. The study will be conducted at three sites. The three sites are (1) Indian Spinal Injuries Centre (tertiary centre) at New Delhi, India, (2) Punjabi University-Patiala (university clinic) at Punjab, India and (3) Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralysed (tertiary centre) at Savar, Bangladesh. Initially, the study was planned for only one site in India. However, the other two sites entered the study 8 months later to speed up recruitment. Pilot data from two of the sites were collected to ensure recruitment was feasible.

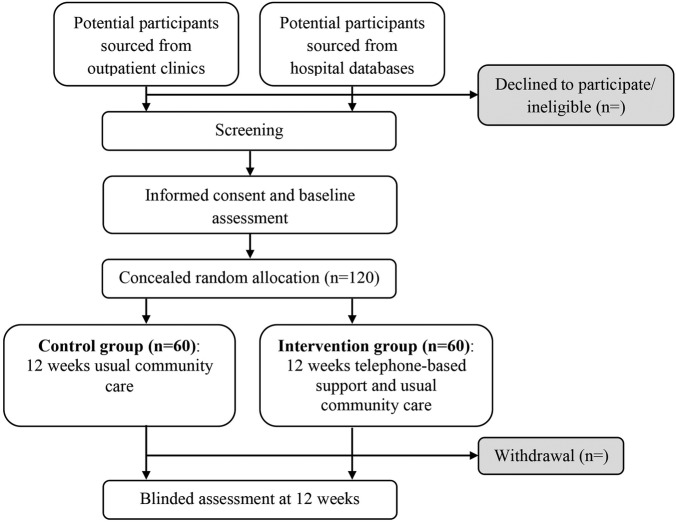

Assignment of intervention

A computer-generated random allocation schedule will be formulated prior to the starting of the study by an independent person located in Australia who is not involved in recruitment. The rand() function in Excel will be used to generate the schedule.18 A blocked allocation (1:1) schedule will be used. Allocation will not be stratified by site. Participants’ allocations will be placed in opaque, sequentially numbered and sealed envelopes which will be kept in Australia. After the participant passes the screening process and completes the baseline assessment, an envelope will be opened and allocation will be revealed by an independent person (figure 1). The participant will be considered to have entered the study at this point. The assessor will be blinded to treatment allocation throughout the course of the study. The statistician conducting the data analysis will also be blinded to group allocation. It is not possible to blind participants or the clinicians delivering the intervention.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Intervention

Participants in the Control group will receive usual community care. That is, they will be given a pamphlet containing information about pressure ulcer management. They will otherwise be left to manage their pressure ulcers at home and without assistance. They will, however, be free to seek any type of help or medical assistance that they deem appropriate and can access.

Participants in the Intervention group will also receive usual community care. That is they will also be given a pamphlet and are free to seek any type of help or medical assistance that they deem appropriate and can access. In addition, they will receive weekly telephone-based support over 12 weeks from an experienced nurse or physiotherapist trained in the management of pressure ulcers in people with SCI. The telephone-based support will be equivalent to 15–25 min/week. The clinicians providing the telephone-based support will be formally trained in pressure ulcer management in Australia and India, or Bangladesh as appropriate. Each time clinicians ring participants, they will reinforce self-help strategies important for managing pressure ulcers, minimising psychological distress and enhancing engagement with life. Specifically, participants and their families will receive education and advice about appropriate seating, bed overlays, cushions, diet, nutrition, wound care and self-care activities. The clinicians will also advise participants about when to seek further medical or nursing attention, how to relieve pressure and when to take bed rest as well as advice on any other related issues which may be contributing to the pressure ulcer (eg, bladder or bowel incontinence, spasticity, depression). Participants will be given goals for each week that will be reviewed, monitored and updated. For example, a goal might include staying on strict bed rest for the next week.

The participants in both groups will be given diaries to record any costs related to the treatment of their pressure ulcers. In addition, they will be contacted once every fortnight to take a verbal transcript from their diaries. The phone calls will also be used to assess costs from those unable to keep diaries because of illiteracy or limited hand function. The following costs will be captured: costs associated with mattresses, pressure-relieving cushions, lost income, medications, dressings, high-protein food, lotions, hospitalisation, travel, incontinence aids and nursing care.

Outcome measures

All assessments will be conducted at the beginning and end of the 12-week study period by an independent, trained nurse who is blinded to the intervention. The assessments will be done at one of the three sites or at the participants’ homes. Participants will be asked not to discuss their group allocation with assessors. The success of blinding will be verified at the end of each participant's assessment by asking assessors to reveal whether they have been unblinded. Any inadvertent unblinding of assessors will be reported.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the size of the pressure ulcer at 12 weeks. This will be assessed using commercially available grid paper designed for this purpose. Length and width will be measured and expressed as cm2. If a participant has more than one pressure ulcer, the pressure ulcer with the most potential to benefit from telephone-based support will be assessed. This will be determined by the assessor at baseline and the same pressure ulcer will be assessed at 12 weeks.

Secondary outcomes

There will be thirteen secondary outcomes. The details of each are as follows:

Severity of the pressure ulcer at 12 weeks will be assessed using the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH) Score V.3.0. The PUSH is the most widely-used tool for assessment of pressure ulcers.19 The PUSH rates pressure ulcers according to the area of the pressure ulcer, amount and type of exudates, and extent of tissue damage. The total scores range from 0 to 17 points with higher scores indicating a severe pressure ulcer.

Undermining distance of the pressure ulcer at 12 weeks will be assessed using a sterile and commercially available scaled probe. The measurements will be taken in four directions, that is, 12:00, 15:00, 18:00 and 21:00.20 All measurements will be recorded in centimetres and then added to derive one tallied score.

Depth of the pressure ulcer at 12 weeks will be measured using a sterile and commercially available scaled probe. Depth will be measured at the centre of the pressure ulcer and recorded in centimetres.21

Pressure ulcer risk factors at 12 weeks will be assessed using the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk.22 23 This outcome has been included to determine whether the telephone-based support influences any of the factors commonly associated with high risk of pressure ulcers in people with SCI. It assesses risk over six domains such as sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction and shear. The total scores range from 6 to 23 points, with lower scores indicating a higher risk for pressure ulcers.

Health-related quality of life at 12 weeks will be assessed using the EuroQol (EQ-5D 5L) Health Survey.24 25 The EQ-5D 5L has two components. The first component captures participants’ health state over five dimensions, namely mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, and can be used to derive utilities and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for cost-utility analysis. The second component (called the Health Thermometer) captures participants’ overall rating of health. Participants are asked to rate their health on a vertical visual analogue scale numbered from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state). The two components will be analysed separately.

Depression at 12 weeks will be assessed using the seven depression items of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.26 The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a widely used self-report questionnaire. The depression items of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale are designed to measure current depression. Scores will be interpreted as indicative of normal or mild, moderate or severe depression. The total scores range from 0 to 21 points, with higher scores indicating severe depression.

Participation at 12 weeks will be assessed using the participation items of the WHO Disability Assessment Scale (WHODAS) 2.0 questionnaire.27 The participant will be asked how much of a problem they have experienced with each item over the past 30 days. Each item is scored on a five-point scale ranging from none (1 point) to extreme/cannot do (5 points). The total scores range from 8 to 40 points, with higher scores reflecting poor participation.

Self-report time for pressure ulcer resolution will be assessed on a weekly basis through one question, namely—‘Is your pressure ulcer healed?’ These data will be collected fortnightly over the telephone and reported as ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Participants’ impression of pressure ulcer status at 12 weeks will be assessed with one question, namely—‘How would you rate the quality of your wound and skin over the affected area?’. Participants will be asked to respond to this question using a 10-point Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)28 anchored at one end with ‘extremely poor’ and at the other end with ‘extremely good’.

Clinicians’ impression of pressure ulcer status at 12 weeks will be assessed with one question namely—‘How would you rate the quality of the wound and skin over the affected area?’. The blinded assessor will be asked to respond to this question using a 10-point NRS anchored at one end with ‘extremely poor’ and at the other end with ‘extremely good’.

Participant confidence to manage the pressure ulcer at 12 weeks will be assessed with one question, namely—‘how confident are you in managing your pressure ulcer at home each day?’. Participants will be asked to respond to this question using a 10-point NRS anchored at one end with ‘not very confident’ and at the other end with ‘very confident’.

Participant satisfaction for healthcare provision at 12 weeks will be assessed with one question, namely—‘how satisfied are you with the services you have received for your pressure ulcer over the last 12 weeks?’ Participants will be asked to respond to this question using a 10-point NRS anchored at one end with ‘very unsatisfied’ and at the other end with ‘very satisfied’.

All questionnaires will be administered to participants in English, Hindi or Bengali.

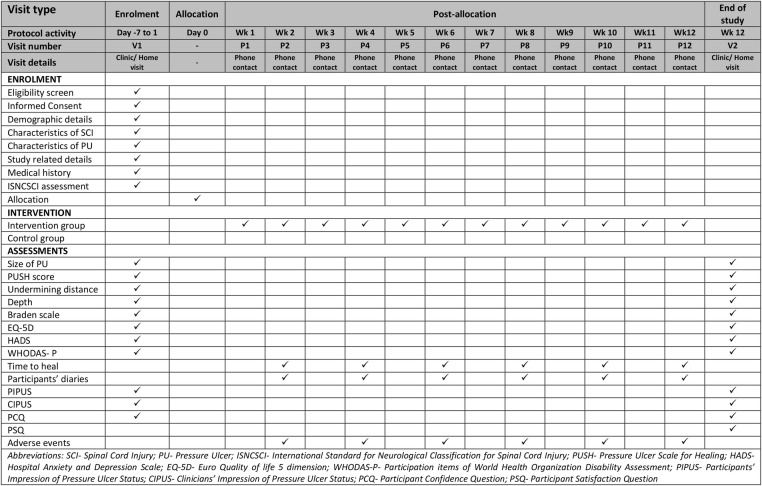

The details of the time schedule of enrolment, intervention, assessments, participants’ visit and phone contacts are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Time schedule of enrolment, intervention, assessments, participants’ visit and phone contacts during the study.

The economic evaluation will be conducted from a societal perspective and will include costs incurred by individuals and healthcare providers. This perspective will be taken because the cost consequences of this intervention may extend beyond the domain of healthcare. The intervention and participants’ healthcare cost will be captured as outlined in table 1. The cost of delivering the intervention will include costs associated with employing clinicians, administration, telephone calls and travel cost where applicable. The costs to the participants for healthcare and other items related to the management of their pressure ulcers will be captured through participant diaries. These will include out-of-pocket expenses associated with specifically purchasing equipment and resources to manage the pressure ulcer such as beds, mattresses, wheelchairs, pressure-relieving cushions, medications, medical supplies, dressings, special high-protein food, lotions and incontinence aids. It will also include costs associated with hospitalisation, travel, nursing care and lost income. Costs associated with insurers’ or governments’ contributions to participants’ healthcare will also be captured through the diaries.

Table 1.

Costs that will be captured for the Control and Intervention groups

| Number | Cost | Control (usual community care) | Intervention (telephone-based support) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Telephone-based support | × | ✓ |

| 2 | Participants’ healthcare facility | ✓ | ✓ |

| 3 | Medical equipment | ✓ | ✓ |

| 4 | Medical supplies | ✓ | ✓ |

| 5 | Participants and their family members’ time | ✓ | ✓ |

| 6 | Carers’ time | ✓ | ✓ |

The economic analyses will include the following:

A within-study cost-effectiveness analysis of telephone-based support for pressure ulcer management compared with usual community care. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) will be determined for the incremental cost per additional cm2 of ulcer healing in the Intervention (telephone-based support) group compared with the Control group.

A cost-utility analysis to present incremental cost per QALYs gained. The ‘cross walk’ from EQ-5D 5L to EQ-5D 3L and Sri Lankan valuation29 of the EQ-5D 3L will be used to get utility weights on a 0–1 scale where 1 represents perfect health and 0 represents death. QALYs will be determined by multiplying utility by duration.

Resources will be valued using standard economic evaluation guidelines.30 Discounting will not be incorporated into the model because the intervention is less than 1 year.

Sample size

A sample size of 120 will be used. This assumes an SD of 30 cm2, loss to follow-up of 15%, correlation with a baseline of 0.6, an α of 0.05 and a minimally worthwhile treatment effect of 10 cm2. The minimally worthwhile treatment effect is based on the assumption that the mean initial size of participants’ pressure ulcers will be 100 cm2. If this is the case, the minimally worthwhile treatment effect will be equivalent to 10% of the mean initial size. If, however, the mean initial size of participants’ pressure ulcers is not 100 cm2, the absolute minimally worthwhile treatment effect will be adjusted post hoc to correspond with 10% of mean initial values.

Quality assurance

To ensure that the interventions are of a high standard and are delivered in accordance with the study protocol, two clinicians who will be providing the intervention will be trained in Australia and India or Bangladesh. They will follow the Canadian Best Practice 9 and National Pressure Ulcers Advisory Panel10 guidelines for the prevention and management of pressure ulcers in people with SCI appropriately modified for LMIC. The two clinicians will contact each other once every month to coordinate and monitor the advice they are providing. In addition, a specialist nurse skilled in pressure management from Australia will provide ongoing support and advice by telephone or in person to the two clinicians.

Data integrity and management

The data will remain confidential throughout the course of the study. Initially, data will be collected on paper-based case report forms (CRFs). The paper-based CRFs will be compiled in participant-specific folders. The designated place will be secured from the public or other staff members of the involved organisations. The local sites will send the CRFs to the University of Sydney in Australia via email. Any information capable of identifying participants will be removed. Data will be managed and transcribed into electronic format in Australia using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at the University of Sydney. REDCap is a secure web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.31

All data will be double entered with automated checks for errors. Data queries will be emailed to the site coordinator and stored on the database. After completion or discontinuation of the study, all records will be kept for a minimum of 15 years at local sites. Access to data during and after the study will only be granted to the designated research team member.

Withdrawal

The study will have the following categories of participant withdrawals:

Withdrawn from study intervention but remain in the study until the 12-week assessment (end of study).

Withdrawn from the entire study with revocation of consent. No further follow-up or data collection will occur.

Lost to follow-up. The participant is lost to follow-up after baseline assessment. This may occur due to death or failure of the study staff to locate the participant. No further follow-up or data collection will occur.

The details of participant withdrawal will be recorded.

Data analysis

All data will be analysed using Stata software V.13 at the University of Sydney, Australia. A separate analysis will be done for all outcomes. Dichotomous data will be analysed using logistic regression and continuous data will be analysed using linear regression. Baseline scores will be included in the models to increase statistical precision.32 The primary analysis will compare the size of pressure ulcers in the Control (usual community care) and Intervention (telephone-based support) groups at 12 weeks. All other analyses will be secondary, including the time for resolution of pressure ulcer, which will be analysed using survival analysis. If more than 5% of data are missing for a particular analysis, multiple imputation will be used to account for missing data, provided the assumption of missing at random appears plausible. The multiple imputation procedure will use all available baseline and follow-up observations.33

For cost-effectiveness, descriptive statistics will be used to summarise the costs and QALYs. The robustness of our costing data will be tested through sensitivity analyses. As in all economic evaluations, the costs captured in this study will most likely be skewed, so non-parametric bootstrap methods will be used for hypothesis tests and interval estimation. A threshold ICER of three times gross domestic product per capita will be used to assess value for money.

The ICER will be estimated as shown in equation (1) as the incremental cost per cm2 reduction in the pressure ulcer area and in the cost-utility analysis as incremental cost per QALY gained in the intervention compared to control.

|

1 |

Non-parametric bootstrapping will be applied to estimate uncertainty around the ICER and the results will be plotted on an incremental cost-effectiveness plane. We will use 2015 US$ as the nominated currency, and will derive ICERs and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves separately for India and Bangladesh.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approvals have been obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee at each site. Participants will be provided with a participant's information sheet and written informed consent will be obtained prior to recruitment and baseline assessment. These documents will be provided in participants’ local language. Each participant will be informed about the study aims, procedures and risks and/or expected benefits. The participants will be informed that their participation is voluntary and that they may leave the study at any time without this having any influence on future treatments provided by their site, clinicians and research team. Participants will be encouraged to discuss the study with family members before making a decision about their participation. They will not be coerced to complete the study.

The result of this study will be submitted for publication to peer-reviewed journals and be presented at national and international conferences.

Monitoring

The study will be overseen and monitored by the research staff who will examine study procedures, ensure data quality and monitor compliance with the study protocol. Adverse events regardless of the seriousness or relationship to the study will be recorded in both groups. All protocol violations will also be recorded. An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board will not be used for this trial because the intervention is unlikely to cause harm and the trial is not sufficiently large enough to warrant stopping it early on the grounds of futility.

Trial status

The first participant was randomised on 28 November 2013, and it is anticipated that the last participant will be recruited at the end of July 2016. The most recent version of the protocol is V.1.3 dated 29 August 2014.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of each of the sites.

Footnotes

Contributors: MA contributed to the conception of the study, the detailed design of the study, all manuscript writing, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. LAH contributed to the conception of the study, the overall design of the study, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. AJH contributed to the conception and detailed design of cost-effectiveness analysis, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. HSC, JVG, IDC and LL contributed to the overall design of the study, critical revision and final approval of the manuscript. NA, SH and PKB contributed to the critical revision and final approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional Ethics Committees of the Indian Spinal injuries Centre, Punjabi University and Centre for Rehabilitation of the Paralysed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kovindha A, Kammuang-Lue P, Prakongsai P et al. . Prevalence of pressure ulcers in Thai wheelchair users with chronic spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 2015. [epub ahead of print 5 May 2015]. doi:10.1038/sc.2015.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment following spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health care professionals. Washington DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allman RM. Epidemiology of pressure sores in different populations. Decubitus 1989;2:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez GP, Garber SL. Prospective study of pressure ulcer risk in spinal cord injury patients. Paraplegia 1994;32:150–8. 10.1038/sc.1994.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne DW, Salzberg CA. Major risk factors for pressure ulcers in the spinal cord disabled: a literature review. Spinal Cord 1996;34:255–63. 10.1038/sc.1996.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scovil CY, Ranabhat MK, Craighead IB et al. . Follow-up study of spinal cord injured patients after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation in Nepal in 2007. Spinal Cord 2012;50:232–7. 10.1038/sc.2011.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoque MF, Grangeon C, Reed K. Spinal cord lesions in Bangladesh: an epidemiological study 1994–1995. Spinal Cord 1999;37:858–61. 10.1038/sj.sc.3100938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garber SL, Rintala DH, Holmes SA et al. . A structured educational model to improve pressure ulcer prevention knowledge in veterans with spinal cord dysfunction. J Rehabil Res Dev 2002;39:575–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houghton PE, Campbell KE, CPG Panel. Canadian Best Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers in People with Spinal Cord Injury: a resource handbook for Clinicians. Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Pressure Ulcers Advisory Panel (NPUAP). Prevention and treatment of pressure wlcers: clinical practice guidelines. Washington DC: NPUAP, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dam A, Datta N, Mohanty UR et al. . Managing pressures ulcers in a resource constrained situation: a holistic approach. Indian J Palliat Care 2011;17:255–9. 10.4103/0973-1075.92354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark F, Pyatak EA, Carlson M et al. . Implementing trials of complex interventions in community settings: the USC-Rancho Los Amigos pressure ulcer prevention study (PUPS). Clin Trials 2014;11:218–29. 10.1177/1740774514521904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schubart JR, Hilgart M, Lyder C. Pressure ulcer prevention and management in spinal cord-injured adults: analysis of educational needs. Adv Skin Wound Care 2008;21:322–9. 10.1097/01.ASW.0000323521.93058.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell TG. Physical rehabilitation using telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:217–20. 10.1258/135763307781458886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swapna N, ed. Telecommunication sector in India—an analysis. MPGI National Multi Conference. International Journal of Computer Applications, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halstead LS, Dang T, Elrod M et al. . Teleassessment compared with live assessment of pressure ulcers in a wound clinic: a pilot study. Adv Skin Wound Care 2003;16:91–6. 10.1097/00129334-200303000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vesmarovich S, Walker T, Hauber RP et al. . Use of telerehabilitation to manage pressure ulcers in persons with spinal cord injuries. Adv Wound Care 1999;12:264–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Shin W. How to do random allocation (randomization). Clin Orthop Surg 2014;6:103–9. 10.4055/cios.2014.6.1.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hon J, Lagden K, McLaren AM et al. . A prospective, multicenter study to validate use of the PUSH in patients with diabetic, venous, and pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 2010;56:26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sussman C, Swanson G. Utility of the sussman wound healing tool in predicting wound healing outcomes in physical therapy. Adv Wound Care 1997;10:74–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Lis MS, Van Asbeck FWA, Post MWM. Monitoring healing of pressure ulcers: a review of assessment instruments for use in the spinal cord unit. Spinal Cord 2010;48:92–9. 10.1038/sc.2009.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braden BJ. The braden scale for predicting pressure sore risk: reflections after 25 years. Adv Skin Wound Care 2012;25:61 10.1097/01.ASW.0000411403.11392.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braden BJ, Bergstrom N. Clinical utility of the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk. Decubitus 1989;2:44–6, 50-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks R, De Charro F. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitehurst DGT, Noonan VK, Dvorak MFS et al. . A review of preference-based health-related quality of life questionnaires in spinal cord injury research. Spinal Cord 2012;50:646–54. 10.1038/sc.2012.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woolrich RA, Kennedy P, Tasiemski T. A preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in 963 people living with a spinal cord injury. Psychol Health Med 2006;11:80–90. 10.1080/13548500500294211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Üstün TB, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S et al. . Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Geneva: WHO Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira-Valente MA, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain 2011;152:2399–404. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:195–8. 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S et al. . Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)—explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health 2013;16:231–50. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vickers AJ, Altman DG. Statistics notes: analysing controlled trials with baseline and follow up measurements. BMJ 2001;323:1123–4. 10.1136/bmj.323.7321.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenward MG, Carpenter J. Multiple imputation: current perspectives. Stat Methods Med Res 2007;16:199–218. 10.1177/0962280206075304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]