Abstract

Fluorinated organic molecules are of interest in fields ranging from medicinal chemistry to polymer science. Herein, we describe a mild, convenient, and versatile method for the synthesis of compounds that bear a perfluoroalkyl group attached to a tertiary carbon, via an alkyl–alkyl cross-coupling. Thus, a nickel catalyst derived from commercially available components (NiCl2·glyme and a pybox ligand) achieves the coupling of a wide range of fluorinated alkyl halides with alkylzinc reagents at room temperature. A broad array of functional groups (e.g., alkyne, aryl iodide, carbamate, furan, ketone, nitrile, phosphonate, primary alkyl bromide, and primary alkyl tosylate) are compatible with the reaction conditions, and highly selective couplings can be achieved on the basis of differing levels of fluorination. A mechanistic investigation has established that the presence of TEMPO inhibits cross-coupling under these conditions and that a TEMPO–electrophile adduct can be isolated.

Keywords: cross-coupling, fluorine, homogeneous catalysis, nickel, zinc

Because fluorinated organic compounds exhibit different properties, including different biological activity, when compared with their nonfluorinated counterparts, interest in the synthesis of fluorinated molecules has increased rapidly in recent years.[1] Whereas impressive progress has been described in the development of general strategies for the preparation of fluorinated aromatic compounds (e.g., Ar–F and Ar–CF3),[2,3] current approaches to the synthesis of molecules that include a Csp3–RF bond (RF = a perfluoroalkyl group) are generally narrow in scope.[3b,4]

For target compounds wherein a perfluoroalkyl group is attached to an sp3-hybridized tertiary carbon,[5,6] alkyl–alkyl cross-coupling with a perfluorinated nucleophile (M–RF) represents a potentially attractive and versatile approach [pathway A in Eq. (1)].[7] Although there are scattered reports of stoichiometric cross-couplings of fluorinated nucleophiles with alkyl electrophiles, catalyzed processes have been limited to activated electrophiles (e.g., allylic, benzylic, and propargylic).[8]

|

(1) |

To the best of our knowledge, an alternative strategy in which a secondary alkyl electrophile that includes a perfluoroalkyl substituent is cross-coupled with an alkylmetal reagent [pathway B in Eq. (1)] has not been described,[9] perhaps due to the deleterious effect of the perfluoroalkyl group at one or more stages in the catalytic cycle.[10,11] In this report, we provide a method that accomplishes this transformation with secondary alkyl halides that bear a variety of perfluoroalkyl substituents [Eq. (2)].

|

(2) |

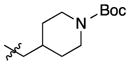

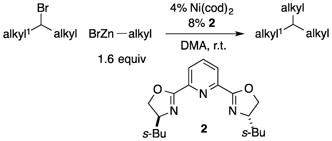

Due to their ready accessibility and their high functional-group compatibility, alkylzinc reagents are attractive partners for cross-coupling processes.[12] Several years ago, we reported a nickel/pybox-based method for coupling unactivated secondary alkyl bromides with alkylzinc reagents in good yield [Eq. (3)].[13]

|

(3) |

When we applied these conditions to the cross-coupling of an alkyl bromide bearing a perfluoroalkyl substituent, we obtained a low yield of the desired product [8%; Eq. (4)]. Debromodefluorination (–BrF)[14] and hydrodebromination of the electrophile were significant side reactions.

|

(4) |

Nevertheless, by modifying the reaction conditions, we can achieve the desired alkyl–alkyl cross-coupling of a fluorinated secondary electrophile in good yield (79%; Table 1, entry 1). The presence of bromide ion is particularly helpful, with NaBr being the most useful source among those that we have examined (entries 1–6).[15] The addition of NaI or NaCl also has a substantial beneficial effect (entries 7 and 8), whereas NaF does not (entry 9). A variety of other ligands, both tridentate and bidentate, furnish significantly lower yields compared with pybox ligand 1 (entries 10–14).[16] The optimized method is not affected by the presence of a small amount of water (entry 15) and is only modestly sensitive to air (entry 16). Changes in temperature (0–40 °C), as well as the use of less nucleophile (1.0 equiv), lead to only a small loss in coupling efficiency (entries 17–19). Cutting the catalyst loading in half results in a moderate decrease in yield (entry 20). In the absence of NiCl2·glyme, essentially no product is formed (entry 21), whereas, in the absence of the pybox ligand 1, cross-coupling is less efficient (entry 22). NiCl2·glyme and ligand 1 are both commercially available and can be handled in the air.

Table 1.

Alkyl–alkyl cross-coupling of a fluorinated secondary electrophile: effect of reaction parameters.[a]

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | variation from the “standard” conditions | yield (%)[b] |

| 1 | none | 79 |

| 2 | no NaBr | 28 |

| 3 | LiBr, instead of NaBr | 75 |

| 4 | KBr, instead of NaBr | 66 |

| 5 | CsBr, instead of NaBr | 61 |

| 6 | (n-Bu)4NBr, instead of NaBr | 74 |

| 7 | Nal, instead of NaBr | 59 |

| 8 | NaCl, instead of NaBr | 66 |

| 9 | NaF, instead of NaBr | 27 |

| 10 | 3, instead of 1 | 5 |

| 11 | 4, instead of 1 | <1 |

| 12 | 5, instead of 1 | 7 |

| 13 | 6, instead of 1 | 17 |

| 14 | 7, instead of 1 | <1 |

| 15 | +0.1 equiv H2O | 79 |

| 16 | under air in closed vial | 60 |

| 17 | 40° C, instead of r.t. | 72 |

| 18 | 0° C, instead of r.t. | 75 |

| 19 | 1.0 equiv of organozinc reagent | 71 |

| 20 | 5.0% NiCl2·glyme, 5.5% 1 | 64 |

| 21 | no NiCl2·glyme | <1 |

| 22 | no 1 | 49 |

All data are the average of two experiments.

The yields were determined through analysis by 19F NMR spectroscopy with the aid of an internal standard.

The scope of this new alkyl–alkyl cross-coupling process is fairly broad (Table 2).[17] Thus, functional groups such as an ether, an acetal, an alkyne, an ester, a phosphonate, a nitrile, and a primary alkyl chloride are compatible with the reaction conditions. Electrophiles that bear higher order perfluoroalkyl substituents are also suitable coupling partners (Table 3).

Table 2.

Alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings of fluorinated secondary electrophiles: scope.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | alkyl | alkyl | yield (%)[b] |

| 1 | CH2CH2Ph |

|

74 |

| 2 | CH2CH2Ph |

|

55 |

| 3 | CH2CH2Ph |

|

61 |

| 4 | CH2CH2Ph |

|

59 |

| 5 | CH2CH2Ph |

|

66 |

| 6 | CH2CH2Ph |

|

70 |

| 7 | CH2CH2Ph |

|

77 |

| 8 |

|

|

64 |

All data are the average of two experiments.

Yield of purified product.

Table 3.

Alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings of fluorinated secondary electrophiles: scope with respect to the perfluoroalkyl group.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | alkyl | alkyl | yield (%)[b] |

| 1 | n-C3F7 |

|

65 |

| 2 | n-C3F7 |

|

54 |

| 3 | n-C3F7 |

|

51 |

| 4 | n-C3F7 |

|

69 |

| 5 | n-C4F9 |

|

67 |

| 6 | n-C4F9 |

|

54 |

| 7 | n-C4F9 |

|

69 |

| 8 | n-C9F19 |

|

66 |

All data are the average of two experiments.

Yield of purified product.

This method is not limited to cross-couplings of alkyl bromides. Thus, under the same conditions, the Negishi reaction of a fluorinated alkyl iodide proceeds in fairly good yield [Eq. (5)].[18]

|

(5) |

Among perfluoroalkyl groups, trifluoromethyl (CF3) is the most commonly encountered, and considerable effort has therefore been dedicated to the development of approaches to the synthesis of various scaffolds that bear this substituent.[3b,4] Although some progress has been described in the generation of targets that include a trifluoromethyl group attached to a tertiary carbon, there is still a need for a general method that proceeds in good yield.[3b,4,19] As illustrated in Tables 4 and 5,[20] our cross-coupling conditions provide versatile access to such compounds and are compatible with a wide array of functional groups (e.g., ether, acetal, ester, alkyne, nitrile, phosphonate, primary alkyl bromide, primary alkyl tosylate, furan, aryl iodide, carbamate, and ketone). On a gram scale in the presence of 5% NiCl2·glyme/5.5% ligand 1, the alkyl–alkyl Negishi coupling depicted in entry 8 of Table 4 proceeds in 80% yield (1.22 g of product).

Table 4.

Alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings to generate trifluoromethyl-substituted products: scope with respect to the nucleophile.[a]

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | alkyl | yield (%)[b] |

| 1 |

|

79 |

| 2 |

|

78 |

| 3 |

|

83 |

| 4 |

|

74 |

| 5 |

|

72 |

| 6 |

|

83 |

| 7 |

|

67 |

| 8 |

|

83 |

| 9 |

|

89 |

All data are the average of two experiments.

Yield of purified product.

Table 5.

Alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings to generate trifluoromethyl-substituted products: scope with respect to the electrophile.[a]

All data are the average of two experiments.

Yield of purified product.

Nucleophile: BrZnCH2CH2CH2CN.

We have observed that, under our standard cross-coupling conditions, replacement of the CF3 substituent of the electrophile with a CF2H group leads to a significantly slower reaction. The enhanced reactivity of the CF3-substituted electrophile enables unusual, highly selective Negishi reactions in the presence of less fluorinated electrophiles (Table 6).[21]

Table 6.

Selective alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings based on fluorine substitution.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unreacted (%) | X | yield (%) | ||

| 0 | 97 | CF2H | 88 | 3 |

| 0 | >99 | CFH2 | 87 | <1 |

| 0 | 99 | CH3 | 87 | 1 |

For an array of nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings of alkyl halides that we have developed, we have suggested that the electrophile may react to furnish an alkyl radical during the oxidative-addition step of the catalytic cycle.[22] For the present method, we have determined that the addition of 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO)[23] substantially inhibits carbon–carbon bond formation [Eq. (6)]. A side product of this Negishi reaction is a TEMPO–electrophile adduct [Eq. (7)], potentially generated from the coupling of TEMPO with an alkyl radical.[24]

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

In conclusion, we have developed a mild and simple nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling method for synthesizing a broad array of compounds that include a tertiary carbon that bears a perfluoroalkyl substituent, thereby providing a general approach to the synthesis of this family of target molecules. A wide variety of functional groups are compatible with the reaction conditions, and the catalyst components are commercially available. The rate of cross-coupling is remarkably sensitive to the level of fluorination of the electrophile, which enables the unusual, highly selective reaction of a substrate that bears a CF3 group in the presence of the corresponding CF2H-substituted compound. In a mechanistic study, we have established that the presence of TEMPO, a radical trap, inhibits carbon–carbon bond formation, and we have isolated a TEMPO-electrophile adduct. Additional studies of nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings of alkyl electrophiles are underway.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Support has been provided by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of General Medical Sciences: R01–GM62871) and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis). We thank Dr. Nathan D. Schley for helpful discussions.

Contributor Information

Yufan Liang, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91125 (USA).

Prof. Gregory C. Fu, Email: gcfu@caltech.edu, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91125 (USA)

References

- 1.For examples of recent monographs that include leading references, see: Roesky HW, editor. Efficient Preparations of Fluorine Compounds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2013. Gouverneur V, Müller K, editors. Fluorine in Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry: From Biophysical Aspects to Clinical Applications. Imperial College Press; London: 2012. Nelson DJ, Brammer CN, editors. Fluorine-Related Nanoscience with Energy Applications. American Chemical Society; Washington, D.C: 2011.

- 2.For Ar–F, see: Watson DA, Su M, Teverovskiy G, Zhang Y, García-Fortanet J, Kinzel T, Buchwald SL. Science. 2009;325:1661–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.1178239.Campbell MG, Ritter T. Chem Rev. 2015;115:612–633. doi: 10.1021/cr500366b.

- 3.For Ar–CF3, see: Cho EJ, Senecal TD, Kinzel T, Zhang Y, Watson DA, Buchwald SL. Science. 2010;328:1679–1681. doi: 10.1126/science.1190524.Alonso C, Martínez de Marigorta E, Rubiales G, Palacios F. Chem Rev. 2015;115:1847–1935. doi: 10.1021/cr500368h.Zhu W, Wang J, Wang S, Gu Z, Aceña JL, Izawa K, Liu H, Soloshonok VA. J Fluorine Chem. 2014;167:37–54.Chen P, Liu G. Synthesis. 2013;45:2919–2939.

- 4.For a review, see: Xu J, Liu X, Fu Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:585–594.

- 5.Proline derivative: Del Valle JR, Goodman M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1600–1602. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020503)41:9<1600::aid-anie1600>3.0.co;2-v.Angew Chem. 2002;114:1670–1672.Qiu X-l, Qing F-l. J Org Chem. 2002;67:7162–7164. doi: 10.1021/jo0257400.For a review on fluorinated amino acids, see: Salwiczek M, Nyakatura EK, Gerling UIM, Ye S, Koksch B. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2135–2171. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15241f.Nucleoside analogue: Jeannot F, Gosselin G, Standring D, Bryant M, Sommadossi JP, Loi AG, La Colla P, Mathé C. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:3153–3161. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00216-x.For a review on the synthesis and applications of fluorinated nucleosides, see: Wójtowicz-Rajchel H. J Fluorine Chem. 2012;143:11–48.Estradiol derivative: Blazejewski J-C, Wilmshurst MP, Popkin MD, Wakselman C, Laurent G, Nonclercq D, Cleeren A, Ma Y, Seo H-S, Leclercq G. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00457-1.

- 6.For a review on applications in medicinal chemistry of compounds that contain a perfluoroalkyl group, see: Prchalová E, Štĕpánek O, Smrček S, Kotora M. Future Med Chem. 2014;6:1201–1229. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.53.

- 7.For examples of discussions of the reluctance of a fluorinated alkyl group to participate in reductive elimination, see: Jover J, Miloserdov FM, Benet-Buchholz J, Grushin VV, Maseras F. Organometallics. 2014;33:6531–6543.Dubinina GG, Brennessel WW, Miller JL, Vicic DA. Organometallics. 2008;27:3933–3938.

- 8.a) Kitazume T, Ishikawa N. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:5186–5191. [Google Scholar]; b) Chen QY, Wu SW. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1989:705–706. [Google Scholar]; c) Miyake Y, Ota S-i, Nishibayashi Y. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:13255–13258. doi: 10.1002/chem.201202853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Miyake Y, Ota S-i, Shibata M, Nakajima K, Nishibayashi Y. Chem Commun. 2013;49:7809–7811. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44434a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Miyake Y, Ota S-i, Shibata M, Nakajima K, Nishibayashi Y. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:5594–5596. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00957f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Indeed, we are not aware of any previous reports of metal-catalyzed alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings of electrophiles (primary, secondary, or tertiary) that include a perfluoroalkyl substituent. Successful reactions to date have been limited to couplings of aryl, alkenyl, and alkynyl nucleophiles with primary alkyl electrophiles that bear a CF3 group (specifically, trifluoroethyl iodide and trifluoroethyl tosylate); none of the studies employs a nickel catalyst or an organozinc reagent. See: Zhao Y, Hu J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:1033–1036. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106742.Angew Chem. 2012;124:1057–1060.Liang A, Li X, Liu D, Li J, Zou D, Wu Y, Wu Y. Chem Commun. 2012;48:8273–8275. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31651j.Feng YS, Xie CQ, Qiao WL, Xu HJ. Org Lett. 2013;15:936–939. doi: 10.1021/ol400099h.Leng F, Wang Y, Li H, Li J, Zou D, Wu Y, Wu Y. Chem Commun. 2013;49:10697–10699. doi: 10.1039/c3cc46601a.See also: Lin X, Zheng F, Qing FL. Organometallics. 2012;31:1578–1582.

- 10.1,1,1-Trifluoro-2-iodoethane has been estimated to be ~17,000 times less reactive than ethyl iodide in an SN2 reaction: Hine J, Ghirardelli RG. J Org Chem. 1958;23:1550–1552.See also: Martinez H, Rebeyrol A, Nelms TB, Dolbier WR., Jr J Fluorine Chem. 2012;135:167–175.

- 11.For a review on the structure, reactivity, and chemistry of fluoroalkyl radicals, see: Dolbier WR., Jr Chem Rev. 1996;96:1557–1584. doi: 10.1021/cr941142c.

- 12.Xu S, Kamada H, Kim EH, Oda A, Negishi E-i. In: Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions and More. de Meijere A, Bräse S, Oestreich M, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2014. pp. 133–278. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou J, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14726–14727. doi: 10.1021/ja0389366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.For a recent example of β-fluoride elimination in the presence of one equivalent of a nickel complex, see: Ichitsuka T, Fujita T, Arita T, Ichikawa J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:7564–7568. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402695.Angew Chem. 2014;126:7694–7698.For a review that includes examples of β-fluoride elimination, see: Amii H, Uneyama K. Chem Rev. 2009;109:2119–2183. doi: 10.1021/cr800388c.

- 15.The beneficial effect of NaBr may be due to an increase in the ionic strength of the reaction medium, activation of the organozinc reagent, etc. For related examples and leading references, see: Son S, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2756–2757. doi: 10.1021/ja800103z.McCann LC, Hunter HN, Clyburne JAC, Organ MG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:7024–7027. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203547.Angew Chem. 2012;124:7130–7133.Fagnou K, Lautens M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:26–47. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<26::aid-anie26>3.0.co;2-9.Angew Chem. 2002;114:26–49.

- 16.Terpyridine: Smith SW, Fu GC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:9334–9336. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802784.Angew Chem. 2008;120:9474–9476.Bathophenanthroline: Zhou J, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1340–1341. doi: 10.1021/ja039889k.Bis(oxazoline): Lou S, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1264–1266. doi: 10.1021/ja909689t.1,2-Diamine: Saito B, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9602–9603. doi: 10.1021/ja074008l.

- 17.Notes: a) Under our standard conditions, the cross-coupling product is stable (e.g., no C–F bond cleavage is observed), and a secondary alkylzinc reagent (cyclopentyl–ZnBr) was not a suitable coupling partner; b) The cross-coupling illustrated in Entry 3 of Table 2 proceeds in 28% ee.

- 18.Under our standard conditions, the corresponding secondary alkyl chloride and secondary alkyl tosylate are not suitable substrates.

- 19.For a recent report of oxidative coupling between secondary alkylboronic acids and TMS–CF3 (10% Cu(OTf)2·0.5(PhH), 40% 3,4,7,8-tetramethyl-1,10-phenanthroline, 3 equiv AgF, 1 equiv Ag(OTs), and 3 equiv KF in DMF at 50 °C; 35–54% yield), see: Xu J, Xiao B, Xie CQ, Luo DF, Liu L, Fu Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:12551–12554. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206681.Angew Chem. 2012;124:12719–12722.

- 20.Under our standard conditions: a) For the reaction illustrated in entry 1 of Table 4, the corresponding alkyl iodide couples in 57% yield, whereas the chloride and the tosylate are ineffective cross-coupling partners; b) Debromodefluorination is the predominant side product; c) An allylic, benzylic, propargylic, and hindered (alkyl = Cy) electrophile, as well as a secondary alkylzinc (cyclopentyl–ZnBr) and a perfluoroalkylzinc reagent, were not suitable coupling partners; c) The cross-coupling illustrated in Entry 5 of Table 4 proceeds in 20% ee.

- 21.Nevertheless, the cross-coupling of the difluoromethyl-substituted electrophile that is illustrated in Table 6 can be achieved in good yield (70%) under related conditions (10% NiCl2·glyme, 11% 1, 1 equiv KBr, DMA/DMF, r.t.). For a review on difluoromethylation, see: Hu J, Zhang W, Wang F. Chem Commun. 2009:7465–7478. doi: 10.1039/b916463d.

- 22.For a recent discussion and leading references, see: Schley ND, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16588–16593. doi: 10.1021/ja508718m.

- 23.Henry-Riyad H, Montanari F, Quici S, Studer A, Tidwell TT, Vogler T. In: Handbook of Reagents for Organic Synthsis. Fuchs PL, editor. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2013. pp. 620–626. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Notes: a) After the TEMPO (15%) has been consumed, cross-coupling resumes; b) In the absence of NiCl2·glyme or of the organozinc reagent, the adduct of TEMPO with the electrophile was not observed; c) Addition of the TEMPO-electrophile adduct to a cross-coupling reaction does not inhibit carbon–carbon bond formation; d) The TEMPO-electrophile adduct is stable to the cross-coupling conditions.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.