Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the responsiveness to change of a modified version of the Work module of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH-W) in a prospective, longitudinal cohort study of active workers.

Methods

We compared change on a 1-year recall modified DASH-W to change on work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity, according to predetermined hypotheses following the Consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments (COSMIN). We evaluated concordance in the direction of change, and magnitude of change using Spearman rank correlations, effect sizes (ES), standardized response means (SRM), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC).

Results

In a sample of 551 workers, change in 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores showed moderate correlations with changes in work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity (r=0.47, 0.44, and 0.36, respectively). ES and SRM were moderate for 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores in workers whose work ability (ES=−0.58, SRM=−0.52) and work productivity improved (ES=−0.59, SRM=−0.56), and larger for workers whose work ability (ES=1.24, SRM=0.68) and work productivity worsened (ES=1.02, SRM=0.61). ES and SRM were small for 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores of workers whose symptom severity improved (−0.32 and −0.29, respectively). Responsiveness of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W was moderate for those whose symptom severity worsened (ES=0.77, SRM=0.50). AUC met responsiveness criteria for work ability and work productivity.

Conclusions

The 1-year recall modified DASH-W is responsive to changes in work ability and work productivity in active workers with upper extremity symptoms.

Keywords: Outcome measures, Occupational injuries, Psychometrics, Musculoskeletal diseases, Work

Introduction

Measurement of health-related quality of life outcomes has become increasingly important to both clinicians and researchers over the last two decades in determining the impact of chronic health conditions on performance of work and daily activities [1, 2]. In studies of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), health-related work outcomes have traditionally included measures such as lost time and disability costs which fail to address how well a person is functioning in his or her job [3–5]. Many questionnaire-based measures have been developed recently to assess a variety of health-related work outcomes such as work role functioning, work disability, and productivity at work [4, 6–8]. In order to measure the effectiveness of interventions, functional measures must be validated and should also be sensitive to clinical changes over time [2]. Responsiveness is the ability of a measure to detect real or meaningful change over time [1, 2, 9].

The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) is a functional outcome measure designed to assess the impact of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders (UE MSD) on physical functioning and symptoms [10–12]. The DASH and its shortened version, the QuickDASH, have shown good reliability and validity in numerous studies for various UE diagnoses and in clinical and working populations [10, 11, 13]. The DASH also has an optional 4-item Work module (DASH-W) to assess the impact of UE disorders on work performance. Despite the numerous studies on the measurement properties of the full DASH and QuickDASH outcome measures, few studies have described the psychometric properties of the DASH-W [14–16]. In particular, responsiveness studies and studies in actively working populations are lacking.

According to Beaton et al., responsiveness is not a static measurement property of a questionnaire, but is specific to the population and setting in which the measure is used [17]. As such, the instrument should be validated for use under those specific circumstances; and responsiveness should be described in relation to a particular type of change that was measured [11]. In addition, studies evaluating the responsiveness of a measure should use a systematic methodology, such as that proposed in the Consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments (COSMIN guidelines), to ensure appropriate conclusions regarding measurement properties of questionnaires [18, 19]. Only one previous study has examined the responsiveness of the DASH-W in active workers with upper extremity (UE) MSDs and MSD symptoms [15]. Fan et al. found the DASH-W to be less responsive than the QuickDASH [15], although the study was limited by a small sample size and responsiveness was assessed relative to changes in UE MSD clinical case status rather than in relation to changes in comparative measures of functional work performance.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the responsiveness to change of a DASH-W using a modified 1-year recall period in a prospective, longitudinal study of active workers. Responsiveness was described according to predetermined hypotheses in comparisons of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W to self-reported work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity.

Materials and Methods

Study participants were originally enrolled in the longitudinal Predictors of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (PrediCTS) study between July 2004 and October 2006, as newly hired workers from participating companies in construction, health care, manufacturing, and biotechnology (n=1107). Data collection consisted of surveys, physical examination of the upper extremities and nerve conduction studies of bilateral median and ulnar nerves at the wrist, and included up to eight years of follow-up time in the original study. The PrediCTS study was originally designed to assess carpal tunnel syndrome and other UE MSDs as the main outcomes. In year five of follow-up, the 1-year recall modified DASH-W was added to all PrediCTS study surveys to assess work outcomes related to UE MSDs, and 29 additional newly hired workers from one of the original participating companies were enrolled in to the study. The present analyses included a convenience sample of 551 participants: 528 of the original 1107 participants and 23 of the 29 participants enrolled in year 5, who completed two PrediCTS study surveys between September 2009 and August 2013 with a minimum two-year follow-up time between surveys, and had complete DASH-W scores on both surveys. The Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board provided the ethical approval of this study. All participants provided written informed consent and were compensated for their participation.

Measures

Questionnaire

Study questionnaires included demographics, workplace physical and psychosocial exposures, UE symptom status, comorbidities, and functional and work limitations due to UE symptoms. 1-year recall modified DASH Work Module (DASH-W)

All participants completed a 4-item scale based on the DASH-W, which measures the impact of UE musculoskeletal conditions on physical work ability and symptoms. Items include using one’s usual work technique, doing one’s usual work due to UE pain, working as well as one would like, and spending one’s usual amount of time working. Participants rated their difficulty with each item on a 5-point scale from “1” “no difficulty” to “5” “unable”. The average score of the 4 items was calculated and transformed to a 0 to 100 scale by subtracting 1 from the average and multiplying by 25, according to the published scoring instructions for the DASH-W. A score was not calculated for the DASH-W if any items were missing (approximately 8% of subjects). Higher scores indicate greater work disability [12, 20]. The standard recall period for the DASH-W is 1 week. We used a 1-year recall period for the DASH-W for consistency with other survey items, including symptom questions based on the Nordic questionnaire [21]. Due to the modified recall period, we refer to the scale used in this study as the 1-year recall modified DASH-W. The instructions for the 1-year recall modified DASH-W stated: “If you had symptoms in the past year, refer to the time when your symptoms were the worst. If you did not have symptoms in the past year, refer to a typical day during the past year.” The original version of the DASH-W is available on the DASH website, (http://www.dash.iwh.on.ca).

Work ability and work productivity

Participants reported presence of recurring symptoms in the past year in three UE regions (hand/wrist/fingers, elbow/forearm, and neck/shoulder/upper arm). Participants with positive symptom reports completed additional survey items from the University of Michigan Upper Extremity Questionnaire (UEQ) [22, 23], regarding limitations in work ability and work productivity for each UE region in which symptoms were present. Participants who did not have symptoms were assigned the lowest possible score for work ability and work productivity items, indicating no work limitations due to UE symptoms. Work ability and work productivity items read as follows:

Work ability: “Think about the past YEAR… Please rate how much these symptoms AT THEIR WORST, have limited your ability to work. Rate your ability to work on a scale from zero ‘no change in ability to work’ to five ‘I was unable to do my regular work’.”

Work productivity: “Please rate your agreement with this statement: In the last year, these symptoms have interfered with my production rates and/or usual standard of quality (mark the one best answer),” on a scale from one “Strongly disagree” to five “Strongly agree”.

Symptom Severity

Participants who reported UE symptoms were asked to rate the severity of their symptoms by indicating the “worst discomfort you have felt in this area in the last year”, from “0” “no discomfort” to “10” “worst imaginable discomfort” [22, 23]. Participants who did not report UE symptoms were assigned a value of “0” for symptom severity.

Statistical analysis

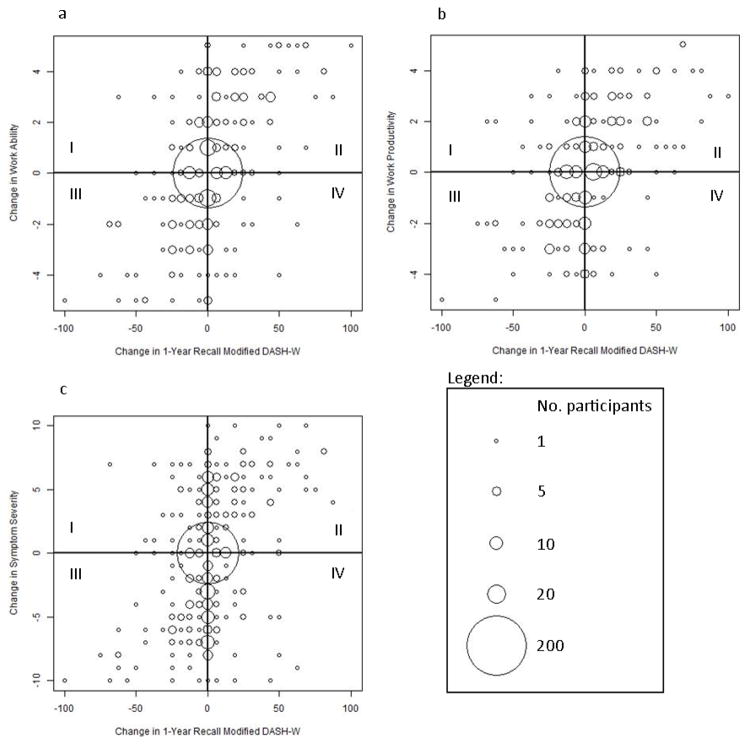

We calculated descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, distribution) for the demographic characteristics of the study population and for each measure. We also described the characteristics of the workers from the overall PrediCTS study who were excluded from the analysis sample. Work productivity was reverse coded so that the directionality of all measures was the same (higher scores were worse). All measures were completed by all participants at baseline and follow-up visits. In order to visually display concordance in the direction of change between the 1-year recall modified DASH-W and each comparison measure, we plotted change scores on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W versus change in work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity.

The responsiveness of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W was assessed in comparison to three measures of change: work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity. Responsiveness of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W was evaluated in two different ways. First, we calculated the Spearman rank correlations between change scores on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W and each comparison measure. Next, change scores were categorized as improved, worsened, or no change for each measure (work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity).

Change in either direction (improved or worsened) was possible, as participants could have either continued working in a physically demanding job and developed symptoms over time, or participants could have changed jobs to less demanding work or sought treatment for symptoms and thus improved. Higher scores on each measure indicated worse performance; therefore, “improved” was a negative change and “worsened” was a positive change. We used a change score for work ability and work productivity of 2 or more points in either direction to indicate a meaningful change, similar to the method used by Beaton et al. in a recent study of the responsiveness of several at-work productivity measures.[7] A change of less than or equal to 1 in either direction was considered no change [7, 24, 25]. For symptom severity, we considered a change of 2 or more points in either direction to indicate a meaningful change, based on the findings of several previous studies that identified a 2-point change on a 0–10 symptom severity scale as clinically meaningful [26–30]. A change in symptom severity of less than or equal to 1 point in either direction was considered no change. If participants reported symptoms in more than one UE region, the largest magnitude of change for each measure (work ability, work productivity, symptom severity) was used for comparison to change on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W in the responsiveness analyses. We calculated the mean change, standard deviation (SD) of change, effect size (ES) (difference in mean scores between baseline and follow-up divided by the SD at baseline) and standardized response mean (SRM) (mean change divided by the SD of change) for the improved, no change, and worsened groups to estimate the magnitude of change over time.

As recommended by the COSMIN panel [18, 19], we formulated the following hypotheses a priori, concerning the expected relationships between the 1-year recall modified DASH-W and work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity:

Hypothesis 1

Direction of change (improved or worsened) in the 1-year recall modified DASH-W would agree with the direction of change for each comparison measure. Increased 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores (indicating higher disability) would correspond with:

increased work ability scores (indicating higher disability),

increased work productivity scores (indicating higher disability), and

increased symptom severity ratings (indicating worse symptoms).

We hypothesized changes in the expected direction using positive correlations for continuous change scores. For categorized measures (improved, worsened), those who improved would have decreased 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores, therefore the ES and SRM would be negative; whereas those who worsened would have increased 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores and thus positive ES and SRM.

Hypothesis 2

The magnitude of the changes on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W would correspond with similar magnitude of changes on each of 3 separate measures:

work ability,

work productivity, and

symptom severity.

We used 3 statistical methods to test this hypothesis, spearman correlations, ES, and SRM. We expected at least moderate correlations between change scores on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W and each comparison measure, considering r= 0.36 to 0.67 as moderate, and 0.68 to 1.0 as strong correlations [31]. We hypothesized that there would be at least moderate or higher ES and SRM for both the dichotomized improved and worsened groups comparing change on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W to each comparison measure (work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity). We considered ES and SRM of 0.50–0.80 to be a moderate effect, and > 0.80 a large effect [32]. ES and SRM for the no change group should be close to zero.

We further investigated how changes on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W compared to the dichotomized improved (yes/no) and worsened (yes/no) groups on each measure, work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity, using receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC). We calculated the area under the ROC curve (AUC) to determine the discriminative ability of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W to distinguish between participants who experienced a meaningful improvement or worsening from those who did not, considering an AUC of at least 0.70 to show responsiveness to change [33]. Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.3 (Statistical Analysis System Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

From the 1136 workers in the PrediCTS cohort, 551 participants comprised the final analysis sample. As shown in Table 1, study participants were young with a mean age of 31.2 years and the majority were male (62%). The most common job categories among the study population at enrollment were construction (34%), office/clerical (29%), and service (26%). The distribution of gender, race, and job category differed between the study population and workers who were not included in the analysis; the study population included a higher proportion of workers who were female, white, and newly employed in office/clerical jobs at enrollment. Among workers included in the analysis sample, there was a relatively low prevalence of self-reported comorbidities from enrollment through the present study period (diabetes 5%, osteoarthritis 5%, rheumatoid arthritis 3%) and of UE MSD diagnoses by a medical professional (CTS 3%, shoulder tendonitis 6%, elbow tendonitis 10%, ulnar neuropathy 1%). During the present study period, few active workers (28%) from this relatively healthy population reported seeking treatment from a medical professional due to UE MSD symptoms. Mean change scores on each comparison measure (work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity) are presented in Table 2. The mean follow-up time between the questionnaires in the included sample was 2.7 years (range 2.0–3.8). A larger proportion of subjects showed changes in symptom severity (improved or worsened) compared with work ability and work productivity; the proportion of subjects who improved and worsened on each respective measure were similar. As shown in Figure 1, 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores appeared to change in the same direction as work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity, as seen in the higher concentration of participants represented by the circles in quadrants II and III.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population at enrollment (n=1136)

| Characteristic | Study population (n=551) | Workers excluded from the analysis a (n=585) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 31.2 (10.6) | 29.7 (10.0) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 29.7 (7.0) | 28.4 (6.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 343 (62) | 402 (69) |

| Female | 208 (38) | 183 (31) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 360 (65) | 343 (59) |

| Hispanic | 5 (1) | 3 (<1) |

| Black/African American | 166 (30) | 214 (37) |

| Asian/Asian American | 10 (2) | 13 (2) |

| Other | 8 (1) | 11 (2) |

| Missing | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Job category, n (%) | ||

| Construction | 188 (34) | 262 (45) |

| Technical | 59 (11) | 66 (11) |

| Office/Clerical | 159 (29) | 76 (13) |

| Service | 145 (26) | 181 (31) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation.

Reasons for exclusion: loss to follow-up, missing either a study baseline or follow-up questionnaire, incomplete DASH-W at either baseline or follow-up, did not meet the minimum two year follow-up time between study baseline and follow-up.

Table 2.

Mean change scores on the comparison measures and frequencies by the category of change

| Scale | Mean |change|a, b |

Improved c n (%) |

No change c n (%) |

Worsened c n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work ability (range 0–5) | 1.1 | 72 (13) | 388 (70) | 91 (17) |

| Work productivity (range 1–5) | 0.86 | 72 (13) | 402 (73) | 77 (14) |

| Symptom severity (range 0–10) | 2.7 | 149 (27) | 274 (50) | 128 (23) |

Change in either direction (improved or worsened) was possible. Mean change scores are reported as the mean of the absolute value of change.

If subjects reported symptoms in more than one region of the upper extremity, the maximum change on each measure (work ability, work productivity, symptom severity) is reported.

Higher scores on each measure indicated worse performance. We used a change score for each item of 2 or more points in either direction to indicate a meaningful change; a change of less than or equal to 1 in either direction was considered no change.

Fig. 1.

Concordance in the direction of change between 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores and 3 comparison measures: a Work ability; b Work productivity; c Symptom severity

Hypothesis 1

Scores on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W changed in the expected direction for work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity, as shown by the positive correlations in Table 3. Additional responsiveness indices including mean change, SD of change, ES, and SRM are presented in Table 4, according to the categories of improved, no change, and worsened. The mean 1-year recall modified DASH-W change scores, ES, and SRM also showed concordance in the direction of change. For each comparison measure (work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity), the “improved” group showed an improved (lower) DASH-W score, indicated by negative mean change scores on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W, and negative ES and SRM. In contrast, “worsened” groups showed worsened (higher) mean change scores on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W, and positive ES and SRM (Table 4).

Table 3.

Spearman correlations between the 1-year recall modified DASH-W change scores and the self-reported work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity change scores (n=551)

| Scale | r | p |

|---|---|---|

| Work ability change a | 0.47 | <0.0001 |

| Work productivity change a | 0.44 | <0.0001 |

| Symptom severity change a | 0.36 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: DASH-W, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, Work module.

If subjects reported symptoms in more than one region of the upper extremity, the maximum change on each measure (work ability, work productivity, symptom severity) was used for comparison to change in 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores.

Table 4.

Responsiveness indices for the 1-year recall modified DASH-W against change in self-reported work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity (n=551)

| Change | n | Baseline mean of 1-year recall modified DASH-W a scores | Mean change of 1-year recall modified DASH-W a scores | SD of change of 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores | Effect Size b | SRM c | AUC d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved e, f | |||||||

| Work ability | 72 | 27.3 | −14.3 | 27.7 | −0.58 | −0.52 | 0.73 |

| Work productivity | 72 | 27.5 | −14.4 | 25.8 | −0.59 | −0.56 | 0.73 |

| Symptom severity | 149 | 16.0 | −6.5 | 22.3 | −0.32 | −0.29 | 0.65 |

| No change e, f | |||||||

| Work ability | 388 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 9.9 | −0.01 | −0.01 | n/a |

| Work productivity | 402 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 11.2 | 0.08 | 0.06 | n/a |

| Symptom severity | 274 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 9.2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | n/a |

| Worsened e, f | |||||||

| Work ability | 91 | 11.5 | 19.2 | 28.3 | 1.24 | 0.68 | 0.75 |

| Work productivity | 77 | 13.6 | 18.8 | 31.0 | 1.02 | 0.61 | 0.74 |

| Symptom severity | 128 | 9.6 | 13.0 | 26.3 | 0.77 | 0.50 | 0.69 |

Abbreviations: DASH-W, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, Work module; SD- standard deviation; SRM- standardized response mean; AUC- area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Higher scores on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W indicate greater disability. Possible range of scores (0–100).

Mean change divided by the SD of the baseline score. Effect size of 0.20–0.50 was considered a small effect, 0.50–0.80 a moderate effect, and > 0.80 a large effect [32].

Mean change divided by the SD of change. SRM of 0.20–0.50 was considered a small effect, 0.50–0.80 a moderate effect, and > 0.80 a large effect[32].

An AUC of at least 0.70 demonstrates responsiveness to change [33].

Higher scores on each measure indicated worse performance; therefore, “improved” was a negative change and “worsened” was a positive change. We used a change score for each item of 2 or more points in either direction to indicate a meaningful change; a change of less than or equal to 1 in either direction was considered no change.

If subjects reported symptoms in more than one region of the upper extremity, the maximum change on each measure (work ability, work productivity, symptom severity) was used for comparison to change in 1-year recall modified DASH-W score.

Hypothesis 2

Larger changes in work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity corresponded with larger changes on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W. Correlations between the 1-year recall modified DASH-W and work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity were moderate (r=0.47, 0.44, and 0.36, respectively) (Table 3). Table 4 describes results for the magnitude of the ES and SRM. Responsiveness of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W was better in relation to work ability and work productivity compared with symptom severity. For participants who reported improved work ability and work productivity, the 1-year recall modified DASH-W showed moderate ES (−0.58, and −0.59, respectively) and SRM (−0.52 and −0.56, respectively). For participants who reported worsened work ability and work productivity, ES were large (1.24 and 1.02, respectively), and SRM were moderate (0.68 and 0.61, respectively). The ES and SRM were small for participants whose symptom severity improved (−0.32 and −0.29, respectively), and moderate for those whose symptom severity worsened (ES=0.77, SRM=0.50).

The AUC for the 1-year recall modified DASH-W showed responsiveness to change for the improved work ability and work productivity groups (0.73 and 0.73, respectively) and for the worsened groups on work ability and work productivity (0.75 and 0.74, respectively). The AUC did not meet the threshold of 0.70 for responsiveness of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W compared with symptom severity for either the improved (0.65) or worsened group (0.69).

Discussion

We evaluated the responsiveness of a 1-year recall modified DASH-W outcome measure in a healthy, actively working population, by comparing changes on the 1-year recall DASH-W to changes in work ability, work productivity, and symptom severity due to UE symptoms. The 1-year recall modified DASH-W detected changes in workers who either improved or worsened on work ability and work productivity, but was less responsive to changes in symptom severity ratings. Responsiveness was larger for the subgroups who reported worsening than for those who reported improvement.

Our first hypothesis that there would be concordance in the direction of change on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W and each comparison measure was confirmed. Our findings showed that increased 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores corresponded with decreased self-reported work ability, decreased self-reported work productivity, and increased symptom severity across all analyses (correlations, mean change scores, ES, and SRM).

Our second hypothesis was also confirmed regarding the expected magnitude of change, according to the strength of correlations we observed between change scores on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W and each comparison measure. The ES and SRM also met our predetermined hypothesis with regards to expected magnitude for the groups who improved and worsened on work ability and work productivity and participants whose symptom severity worsened. The 1-year recall modified DASH-W was not responsive to change among participants whose symptom severity improved. The lower baseline mean 1-year recall modified DASH-W score among the improved group for symptom severity (16.0 points) should be noted, however, in relation to the higher baseline mean 1-year recall modified DASH-W scores for the improved groups on work ability (27.3) and work productivity (27.5). Although workers’ overall symptom severity ratings improved, their functional work performance did not improve as much. The implication of this finding is that functional measures may be more sensitive to change among working populations than clinical indicators of change (symptom severity). This finding also highlights the importance of selecting an appropriate external scale used for comparison in responsiveness analyses, as responsiveness may appear much different in comparison to different change indices [11].

We found only one previous study that assessed the responsiveness of the DASH-W, which was also conducted in a working population. Fan et al. assessed the responsiveness of the standard 1-week recall version of the DASH-W to changes in clinical outcome defined as incident and recovered MSD and symptomatic cases over a 1-year follow-up [15]. As in our study, Fan et al. found that the DASH-W changed in the expected direction for the respective improved (recovered) and worsened (incident) groups. Despite both study populations being comprised of active workers, Fan et al. selected more impaired workers, all of whom had symptoms or met an MSD case definition of symptoms and signs, which would have been more similar to a clinical population than our working group, yet both studies showed the expected direction of change for the DASH-W [15]. The magnitude of change between the two studies differed, which may have been due to the selection of more severely symptomatic workers in the Fan et al. study.

There were also some differences in the study designs that should be noted. The Fan et al. study used the standard 1-week recall version of the DASH-W, whereas our study used a modified 1-year recall period [15]. The total follow-up time in the Fan et al. study was 1 year, whereas our analyses used a minimum of 2 years follow-up time [15]. We compared change on the 1-year recall modified DASH-W to reported change in two measures of work performance (work ability and work productivity) and one measure of health status (symptom severity) whereas Fan et al. assessed change in health status (symptomatic and MSD case status). Despite the differences in study design, both studies add important information to the current literature regarding the responsiveness of the DASH-W. Fan et al. provided important information regarding how the DASH-W performs relative to a change in clinical case status, whereas the present study describes responsiveness relative to measures of work performance and symptoms that are commonly used in workplace-based studies [15].

A few limitations of the present study should be noted. We did not ask participants to identify when symptoms were experienced during the recall period, “in the last year”, thus some participants may have been recalling outcomes experienced as much as 1 year prior, while others could have reported on more recent events. A recent study in orthopedic patients showed that patients were able to accurately recall their functional limitations as measured by the QuickDASH for two years following a baseline clinical evaluation [34]. Long recall periods for self-reported outcome measures may be criticized for the potential to miss intermittent outcomes; however, our recall period likely captured the majority of the chronic MSD cases which progress slowly. Furthermore, by asking all participants to report on the time when symptoms were “at the worst”, our recall period avoids the potential for missing short-term symptom fluctuations. Our recall period standardizes the recall for all participants to the worst time in the disease process rather than a single, short-term time period (1 week) which would likely miss fluctuations in symptom or disability outcomes. Finally, despite our large sample size, there were not enough cases to analyze responsiveness of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W by specific MSD diagnoses; however, we provided descriptive information for the frequency of MSD outcomes in the population in Table 1.

An important strength of our study is the large sample size with a comprehensive set of clinical and functional measures available for comparison on the responsiveness of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W over time. The magnitude of the changes measured by ES, SRM, and AUC showed that the 1-year recall modified DASH-W may be sensitive to change in a working population and in epidemiological studies. Despite several previous studies that have examined the responsiveness of the full versions of the DASH and QuickDASH in a variety of clinical populations [10, 11, 13], only one previous publication assessed responsiveness of the 4-item DASH Work module in a working population, rather than in a clinic population [15]. Our study is the first to correlate change scores on a modified version of the DASH-W with change on other work performance measures over time. Tang et al. found moderate correlations between the standard 1-week recall DASH-W and self-reported single-items on work productivity and work ability in cross-sectional comparisons of a clinic population of patients attending a specialty clinic for elbow and shoulder disorders, but they did not assess sensitivity to change over time [14]. Thus our study adds a significant contribution to fill the current gaps in the literature regarding the sensitivity of the DASH-W to change.

The findings of this study provide support for the responsiveness of the 1-year recall modified DASH-W for monitoring change in work performance in active workers due to UE MSD symptoms. Responsiveness is a dynamic measurement property that is affected by numerous factors including setting/population as well as methodological issues such as recall period and external comparison scales. In working populations, work performance measures may be more sensitive to clinical change than changes in symptoms or case status.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC/NIOSH) (grant # R01OH008017-01) and by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (CTSA) (grant # UL1 TR000448) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This research was also supported (in part) by a pilot project research training grant from the Heartland Center for Occupational Health and Safety at the University of Iowa. The Heartland Center is supported by Training Grant # T42OH008491 from the CDC/NIOSH. The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIOSH, NCATS, or NIH. All funding sources had no direct role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit this work for publication. None of the study sponsors were involved in the development of this manuscript. The authors wish to thank members of the research team for their contributions to the preparation of this manuscript including Anna Kinghorn, Nina Smock, and Angelique Zeringue. The authors also wish to thank Dorcas Beaton and Carol Kennedy for their thoughtful insights regarding the study design.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Ann Marie Dale, Bethany T. Gardner, Skye Buckner-Petty, Jaime Strickland, Vicki Kaskutas, and Bradley Evanoff declare that they have no relevant conflict of interest.

Informed Consent: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Contributor Information

Ann Marie Dale, Division of General Medical Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8005, 660 S. Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63110 USA.

Bethany T. Gardner, Division of General Medical Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8005, 660 S. Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63110 USA

Skye Buckner-Petty, Division of General Medical Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8005, 660 S. Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63110 USA.

Vicki Kaskutas, Division of General Medical Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8005, 660 S. Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63110 USA.Program in Occupational Therapy, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8505, 4444 Forest Park Avenue, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63108 USA.

Jaime Strickland, Division of General Medical Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8005, 660 S. Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63110 USA.

Bradley Evanoff, Division of General Medical Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8005, 660 S. Euclid Avenue, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63110 USA.

References

- 1.Deyo RA, Diehr P, Patrick DL. Reproducibility and responsiveness of health status measures. Statistics and strategies for evaluation. Control Clin Trials. 1991;12(4 Suppl):142S–58S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(05)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyatt G, Walter S, Norman G. Measuring change over time: Assessing the usefulness of evaluative instruments. J Chron Dis. 1987;40(2):171–8. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz JN, Punnett L, Simmons BP, Fossel AH, Mooney N, Keller RB. Workers’ compensation recipients with carpal tunnel syndrome: the validity of self-reported health measures. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(1):52–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amick BC, Lerner D, Rogers WH, Rooney T, Katz JN. A review of health-related work outcome measures and their uses, and recommended measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3152–60. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramada JM, Delclos GL, Amick BC, III, Abma FI, Pidemunt G, Castano JR, et al. Responsiveness of the Work Role Functioning Questionnaire (Spanish version) in a general working population. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(2):189–94. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lofland JH, Pizzi L, Frick KD. A review of health-related workplace productivity loss instruments. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(3):165–84. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaton DE, Tang K, Gignac MAM, Lacaille D, Badley EM, Anis AH, et al. Reliability, Validity, and Responsiveness of five at-work productivity measures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2010;62(1):28–37. doi: 10.1002/acr.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad M, Wahlqvist P, Shikiar R, Shih YCT. A review of self-report instruments measuring health-related work productivity. A patient-reported outcomes perspective. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22(4):225–44. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Centor RM. Assessing The Responsiveness of Functional Scales to Clinical Change: An Analogy to Diagnostic Test Performance. J Chron Dis. 1986;39(11):897–906. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaton DE, Davis AM, Husdak P, McConnell S. The DASH (Disabilities of the arm, shoulderm and hand) outcome measure: What do we know about it now? British Journal of Hand Therapy. 2001;6:109–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, Wright JG, Tarasuk V, Bombardier C. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2001;14(2):128–46. doi: 10.1016/S0894-1130(01)80043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) Am J Ind Med. 1996;29(6):602–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy CA, Beaton DE, Smith P, Van Eerd D, Tang K, Inrig T, et al. Measurement properties of the QuickDASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) outcome measure and cross-cultrual adaptations of the QuickDASH: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(9):2509–47. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang K, Pitts S, Solway S, Beaton D. Comparison of the psychometric properties of four at-work disability measures in workers with shoulder or elbow disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(2):142–54. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan ZJ, Smith CK, Silverstein BA. Responsiveness of the QuickDASH and SF-12 in Workers with Neck or Upper Extremity Musculoskeletal Disorders One-Year Follow-Up. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(2):234–43. doi: 10.1007/s10926-010-9265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.House R, Wills M, Liss G, Switzer-McIntyre S, Lander L, Jiang D. DASH work module in workers with hand-arm vibration syndrome. Occup Med (Lond) 2012;62(6):448–50. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqs135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Katz JN, Wright JG. A taxonomy for responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1204–17. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick D, et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick D, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. International consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes: results of the COSMIN study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute for Work and Health. The QuickDASH Outcome Measure: Information for Users. Toronto, ON, Canada: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, Vinterberg H, Bieringsorensen F, Andersson G, et al. Standardized Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Applied Ergonomics. 1987;18(3):233–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franzblau A, Salerno DF, Armstrong TJ, Werner RA. Test-retest reliability of an upper-extremity discomfort questionnaire in an industrial population. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23(4):299–307. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salerno DF, Franzblau A, Armstrong TJ, Werner RA, Becker MP. Test-retest reliability of the Upper Extremity Questionnaire among keyboard operators. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40(6):655–66. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:407–15. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, Griffith LE. Determining a minimal important change in disease specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:81–7. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine. 2005;30(11):1331–4. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000164099.92112.29. 00007632-200506010-00018 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrar JT, Portenoy RK, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Strom BL. Defining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measures. Pain. 2000;88:287–94. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–58. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. S0304-3959(01)00349-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostelo RWJG, Deyo RA, Stratford P, Waddell G, Croft P, Von Korff M, et al. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain. Spine. 2008;33(1):90–4. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri A, Ciapetti A, Grassi W. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:283–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor R. Interpretation of the correlation coefficient: a basic review. Journal of Diagnostic Sonography. 1990;6(1):35–9. doi: 10.1177/875647939000600106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, van der Windt DAWM, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stepan JG, London DA, Boyer MI, Calfee RP. Accuracy of patient recall of hand and elbow disability on the QuickDASH questionnaire over a two-year period. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95-A(22):e176.1–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]