Abstract

The posterior sagittal route is utilized as an alternative to the abdominal and perineal routes for the operation of a complete rectal prolapse (syn. procidentia). A mesh is interposed between the rectum and sacrum. The mesh also acts as a sling suspended from the sacrum. The levator muscle is repaired from behind. Anal encirclement is made to correct a patulous anus.

Keywords: Procidentia, Posterior sagittal route, Mesh rectopexy, Anal encirclement band

Introduction

Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty described by Pena and Devries [1] for the reconstruction of a high anorectal malformation is based upon the principle of midline exposure of the anorectal region below the sacrum. A funnel-like muscular structure extends as a continuum from a pelvic insertion, namely the pelvic bone, pubic rim, and the lowest portion of the sacrum all the way down to the skin. It is formed by the levator ani at its upper part and the external sphincter at the lower part [1, 2]. After exposure, a polypropylene mesh is placed behind the rectum; half of the mesh remains in front of the sacrum, and the lower half is below the sacrum. The mesh is fixed to the margins of the sacrum and coccyx (Fig. 1). The repair is supplemented with a polypropylene anal encirclement band [3].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the funnel-shaped muscle complex and the site of placement of the mesh. a Lateral view, b posterior view (LA = levator ani, ESM = external sphincter muscle)

Procedure

Four patients with complete rectal prolapse were operated on with the new procedure between 2010 and 2012 (Table 1). Before operation, the prolapse was reduced, and a Foley urethral catheter was placed in situ. The patients were placed on prone jackknife position. The hips were kept abducted and legs supported on stands with knees remaining flexed. A midline skin incision was made from behind the sacrum to 2.5 cm behind the anal verge. Subcutaneous tissue and the striated muscle complex were divided with a diathermy knife, remaining strictly in the midline to reach the wall of the rectum. Below the coccyx, Waldeyer’s fascia was incised, and the presacral space was blindly dissected with a finger as high as possible. The lateral walls of the rectum were dissected clear of the surrounding muscle and fat. A polypropylene mesh was partially split in the form of an inverted Y. The unsplit half of the mesh was placed in front of the sacrum and was fixed in position with polypropylene stitches to the margins of the sacrum and coccyx. Split halves of the mesh were wrapped around the posterior and lateral walls of the rectum and fixed with a series of interrupted 3-0 polypropylene sutures. A second transverse incision was made 3 cm in length between the anus and scrotum/vagina. Through this wound tunnels were created around both the sides of the anus to reach the previously made sagittal incision. A 1.5-cm-wide strip of polypropylene mesh was placed around the proximal anal canal. The strip was tightened allowing an anal diameter only large enough to admit one finger. Few stitches were applied on the encircling band to fix that with the lower ends of the inverted Y-shaped mesh as well as to the sphincter muscle mass to prevent its displacement and folding. Reapproximation of the divided levator sling and the muscle complex was made in the midline with 3-0 polyglycolic acid suture. The skin closure was made with 4-0 polyglycolic acid suture (Fig. 2). A corrugated drain was used in one of the cases. Mean operation time was 1 h 45 min. All the patients were discharged between the 7th and 10th days. In 1–3-year follow-up, all the patients remained well without any recurrence, erosion of the mesh into the rectum, or any sexual dysfunction.

Table 1.

The patients operated on for rectal prolapse with PSMR and anal encirclement through the posterior sagittal route

| Patient sr. no. | Sex | Age | Nature of prolapse | Previous operation for prolapse | Anesthesia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 23 years | Complete | Nil | General |

| 2 | Male | 26 years | Complete, recurrent | Thiersch’s operation 6 months back | General |

| 3 | Male | 55 years | Complete, recurrent | Abdominal suture rectopexy 1 year back | Spinal |

| 4 | Female | 43 years | Complete | Nil | Spinal |

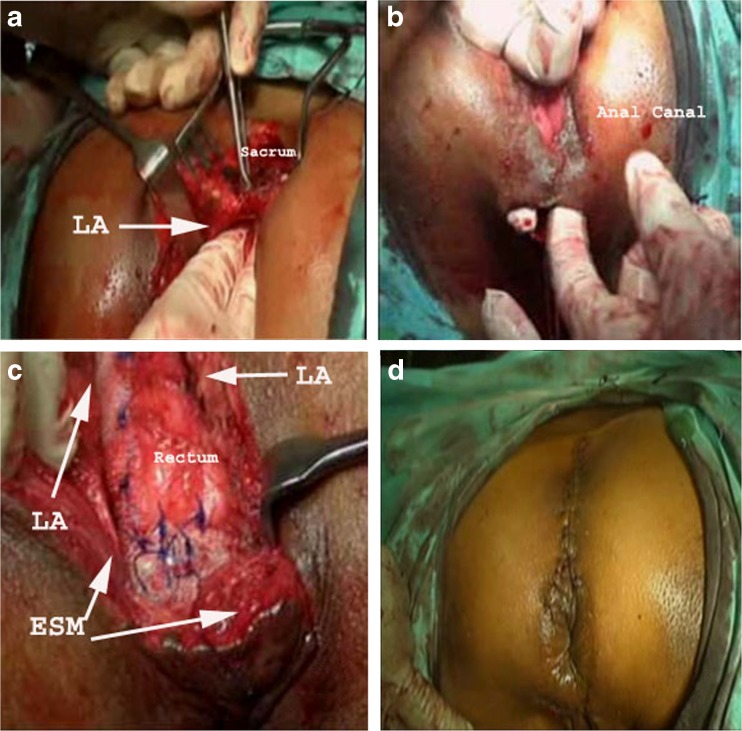

Fig. 2.

Operative snaps. a Levator ani (LA) fibers are split and retracted, and a space is created between sacrum and rectum. b Two tunnels are prepared on the sides of the anal canal for placement of the polypropylene band. c After the rectopexy and placement of the anal band, the levator ani (LA) and external sphincter complex (ESM) will be sutured behind at the midline. d Sagittal and perineal incision lines sutured—final appearance

Discussion

Numerous types of repair for procidentia have been described. The different approaches (abdominal or perineal), procedures (open or laparoscopic), and techniques (repair of the levator sling, dissection at the hollow of the sacrum, suture rectopexy, rectal slings, resection of redundant gut, Altemeier’s perineal proctosigmoidectomy, Delorme’s mucosal excision and plication, etc.) are all in vogue for long since. Broden and Snellman were able to show convincingly that procidentia is basically full-thickness rectal intussusception starting about 3 in. above the dentate line [4]. During posterior sagittal mesh rectopexy along with band encirclement around the proximal anus, the site of initiation for the rectal prolapse is given special attention. Pearl et al. [5] performed posterior sagittal anorectoplasty successfully in a 1-year-old girl for recurrent rectal prolapse without any mesh. Some merits of posterior sagittal mesh rectopexy (PSMR) with anal encirclement are the following: (1) it can be applied as a primary procedure or for recurrence in young, middle-aged, or elderly patients; (2) presacral dissection is made possible, avoiding the abdomen; (3) there is minimum dissection inside the pelvis and around the proximal rectum, protecting the pelvic splanchnic nerves; (4) the mesh promotes fibrosis and serves as a rectal sling; (5) the posterior part of the levator sling is easily accessed and repaired below the sacrum; and (6) the anal encircling band can be suitably and securely placed around the proximal anus.

Conclusion

For repair of complete rectal prolapse, the principles of presacral dissection, placement of a nonabsorbable mesh between rectum and sacrum, rectal sling, repair of levator sling, and anal encirclement with mesh are not new. All these principles are combined and contemplated easily, safely, and satisfactorily through the posterior sagittal route.

References

- 1.Pena A, Devries PA. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty: important technical considerations and new applications. J Pediatr Surg. 1982;17:796–811. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(82)80448-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chatterjee Subir K. Surgery of pediatric anorectal malformation. New Delhi: Viva Books Pvt Ltd; 2005. pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saino AP, Halme LE, Husa AI. Anal encirclement with polypropylene mesh for rectal prolapse and incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:905–908. doi: 10.1007/BF02049706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL (eds) (2008) Sabiston textbook of surgery, 18th edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, Vol 2, Section X–XIII, p 1418

- 5.Pearl RH, Ein SH, Churchill B. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty for pediatric recurrent rectal prolapse. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24(10):1100–2. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(89)80228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]