Abstract

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma is a rare tumour, accounting for only about 1 % of all pancreatic tumours. The long-term survival for patients with acinar cell carcinoma is significantly better than the long-term survival of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. As no large series of patients with acinar cell carcinomas exist, our understanding of this disease comes mainly from small case series and case reports. Aggressive surgical resection with negative margins is associated with long-term survival in these more favourable pancreatic cancers. There are no clear treatment guidelines for patients in whom complete surgical resection with curative intent is not possible. Acinar cell carcinomas are chemoresponsive to agents that have activity against pancreatic adenocarcinomas and colorectal carcinomas because of the shared genetic alterations between these cancers. The role of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemoradiotherapy remains unproven. The aim of this article is to present current knowledge on acinar cell carcinoma and comprehensive review of available literature.

Keywords: Acinar cell carcinoma, Pancreas, Surgery, Unproven role of chemotherapy

Introduction

Acinar cell neoplasms are epithelial neoplasms defined by their morphological resemblance to acinar cells and the production of pancreatic exocrine enzymes. Despite the fact that acinar tissue constitutes most of the pancreas, pancreatic neoplasms exhibiting predominantly acinar differentiation are rare. Acinar differentiation in neoplastic cells is defined as the production of zymogen granules that contain pancreatic exocrine enzymes [1]. Almost all acinar neoplasms of the pancreas are solid and malignant. Rare benign cystic, malignant cystic and mixed carcinomas also exist [2]. The only benign acinar neoplasm reported is acinar cell cystadenoma. Acinar cell neoplasms can be classified as follows:

Malignant solid neoplasm–acinar cell carcinoma (ACC)

Benign cystic neoplasm–acinar cell cystadenoma

Malignant cystic neoplasm–acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma

- Mixed carcinoma

- Mixed acinar–neuroendocrine carcinoma

- Mixed acinar–neuroendocrine–ductal carcinoma

- Mixed acinar ductal carcinoma

Acinar cell carcinoma, also known as acinic cell carcinoma, is a malignant epithelial neoplasm composed of cells with morphological resemblance to acinar cells and with evidence of exocrine enzyme production by the neoplastic cells. Significant endocrine or ductal components (not more than 25 % of the neoplastic cells) are lacking. Rare cases with macroscopic non-degenerative cyst formation have been reported as acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma. Acinar cell carcinoma exhibit no specific site predilection and may arise in any portion of the pancreas but are somewhat slightly more common in the head. The aetiology of the acinar cell carcinoma is unknown and there are no documented precursor lesions.

Epidemiology

Acinar cell carcinomas represent approximately 1–2 % of adult exocrine pancreatic neoplasms and most occur in late adulthood, with a peak incidence in the 60s. Fifteen percent of the paediatric exocrine pancreatic neoplasms are acinar cell carcinomas. Paediatric cases account for only 6 % of acinar cell carcinomas, usually seen in patients of 8–15 years of age, and the entity is uncommon between the ages of 20 and 40 years [3, 4]. Males are affected more frequently than females with a male to female ratio of 3.6:1. There are no known racial associations.

Clinical Features

Most acinar cell carcinomas present with non-specific symptoms which are related to the mass effect of the neoplasm but sometimes, they may be an incidental finding on microscopic examination. Common non-specific symptoms include weight loss (52 %), abdominal pain (32 %), nausea and vomiting (20 %), melena (12 %), and weakness, anorexia or diarrhoea (8 %) [5]. In contrast to ductal adenocarcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma rarely results in bile duct obstruction and jaundice, which occurs only in 12 % of patients [3]. Bile duct obstruction is rare in acinar cell carcinoma because they generally push rather than infiltrate into adjacent structures.

A characteristic paraneoplastic syndrome has been described with these tumours due to elevated levels of circulating lipase. Approximately 10–15 % of patients develop lipase hypersecretion syndrome, in which massive quantities of lipase are released by the neoplasm into the bloodstream with levels reaching over 10,000 U/dl, with clinical symptoms including multiple nodular foci of subcutaneous fat necrosis and polyarthralgia due to sclerotic lesions in cancellous bone because of fat necrosis in the bone [5, 6]. Peripheral blood eosinophilia and parathyropathies also occur. In some patients, the lipase hypersecretion syndrome is the first presenting sign of the tumour, while in others, it develops following tumour recurrence. In most of the cases, these patients have hepatic metastasis at the time the syndrome develops, although occasionally, there is an extremely large organ-limited primary carcinoma. Successful surgical removal of the neoplasm may result in the normalisation of the serum lipase levels and resolution of the symptoms.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Analysis

Other than an elevation of serum lipase levels associated with the lipase hypersecretion syndrome, there are no specific laboratory abnormalities in patients with acinar cell carcinoma. A modest elevation in serum lipase levels may be detected even in those patients without the lipase hypersecretion syndrome. Serum tumour markers are not consistently elevated in patients with acinar cell carcinoma. A few cases show increased serum alpha-fetoprotein level [7]. Serum glycoprotein markers such as CA 19–9 are usually not elevated.

Radiologic Features

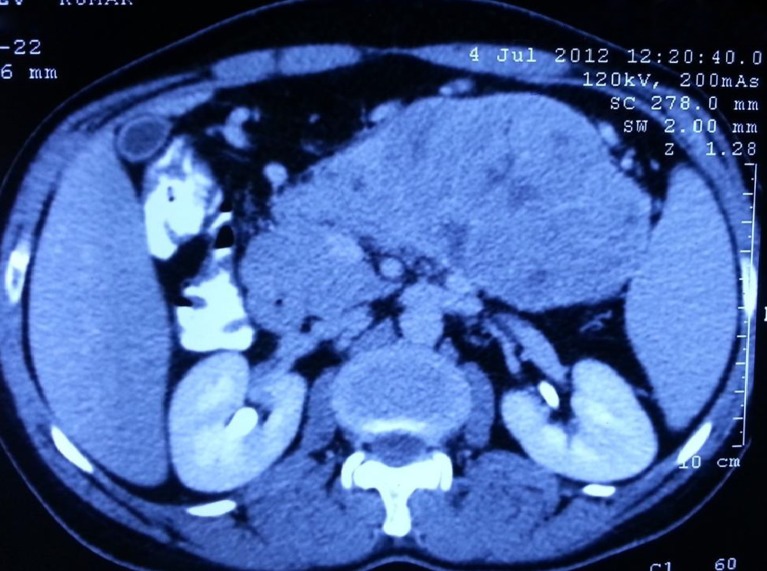

Most acinar cell carcinomas are large with a mean size of 10 cm and are easily appreciated on radiologic examination [8]. The mass formed by acinar cell carcinomas is often better defined than those formed by ductal adenocarcinomas, which sometimes help in distinguishing the two entities, but the radiologic findings are non-specific (Fig. 1). Computerised tomography and magnetic resonance imaging reveal well-defined, large, round to oval masses that enhance homogenously less than the surrounding pancreas or show cystic areas.

Fig. 1.

CECT showing a large heterogeneously enhancing well-defined intrapancreatic lesion 12 × 7.5 cm in the body and tail region with few small non-enhancing areas

Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy

Acinar cell carcinomas are generally sampled cytologically via fine-needle aspiration biopsy since they do not typically invade the bile duct or duodenum and are therefore not usually accessible by brush cytology. FNA reveals abundant material with cells depicting varying degrees of acinar differentiation and lack ductal and endocrine cells. The aspirates contain mostly cohesive fragments forming acini, cellular cords or solid nests of neoplastic epithelium [9]. The neoplastic cells do not show the compact, orderly lobular “bunch of grapes” arrangement of normal epithelium. The cells usually have an eccentrically placed nuclei and granular, often basophilic cytoplasm. The neoplastic cells often lose their fragile cytoplasm, resulting in numerous naked nuclei resembling lymphocytes in the smear background.

Macroscopy

At the time acinar cell carcinomas are detected, most are large averaging 10 cm in diameter; acinar cell carcinomas less than 2 cm are rare. They are generally circumscribed and may be multinodular; nodules are soft and vary from yellow to brown. Central necrosis is often present and cystic degeneration may also be present. Occasionally, the neoplasm is found attached to the pancreatic surface. Because of their circumscribed nature, acinar cell carcinomas usually displace adjacent structures (Fig. 2) but extension into adjacent structures, such as duodenum, spleen or major vessels may occur. In rare cases, grossly identifiable finger-like projections extend beyond the periphery of the main tumour into the pancreatic duct [10].

Fig. 2.

Intra-operative picture showing approximately 12 × 10-cm sized mass present in body of pancreas reaching up to the tail of pancreas, and abutting splenic vessels, and transverse mesocolon but free from stomach, transverse colon, duodenum and spleen

Microscopy

Acinar cell carcinomas classically are composed of nests of pyramidal cells clustered around small lumina. The cells have basally oriented nuclei, single prominent nucleoli and granular cytoplasm. Some acinar cell carcinomas, however, are less well differentiated and grow as solid sheets of more poorly differentiated cells. In these latter instances, the presence of single prominent nucleoli in the neoplastic cells can be a clue to the diagnosis (Fig. 3a). The neoplastic cells are arranged in several different architectural patterns, the pure solid and acinar patterns account for the majority of them, each constituting the bulk of the neoplasm in 30–40 % of cases, and an equal mixture of the two patterns is seen in the remaining third. Less common architectural patterns include a glandular pattern, trabecular pattern and gyriform pattern [3]. Microscopically, there is nearly always evidence of invasive growth.

Fig. 3.

a Microscopic picture showing cells with mild pleomorphism, round in shape, with indistinct cell membranes, moderate amount of granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, round to oval hyperchromatic nuclei, 4–5 mitoses/hpf, b PAS staining with diastase shows granular cytoplasmic positivity

The striking eosinophilic granularity of the cytoplasm reflects the presence of cytoplasmic zymogen granules. In some well-granulated carcinomas, this feature is readily identifiable in routinely stained sections. In most cases, however, the cytoplasmic granularity is not well developed, so special stains are generally needed to document the presence of pancreatic exocrine enzymes. Zymogen granules in 95 % of the cancers are positive with the periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain, and resistant to diastase digestion (dPAS) (Fig. 3b). Many acinar cell carcinomas, however, do not contain sufficient quantities of zymogen granules for this stain to provide convincing results. The butyrate esterase stain detects the presence of enzymatically active lipase. This stain demonstrates lipase in the neoplastic cells and is highly specific for acinar differentiation; however it is not widely utilised and is only positive in 70–75 % of cases.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical labelling for pancreatic enzyme production is helpful in confirming the diagnosis of acinar cell carcinoma. Antibodies are available against trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase and elastase. The first three of these are most widely employed, and labelling for trypsin (95 % of cases) and chymotrypsin has the highest degree of sensitivity, lipase (70–80 % of cases) is less commonly identified. Pancreatic amylase is rarely detected in acinar cell carcinomas despite its presence in non-neoplastic acinar cells [3, 9, 11].

Acinar cell carcinomas also commonly have focal endocrine differentiation. Scattered cells in 35–54 % of cases immunolabel for chromogranin or synaptophysin. Rarely, peptide hormones such as glucagon or somatostatin are expressed in acinar cell carcinomas.

Acinar call carcinomas produce CK8 and CK18 and are therefore positive for CAM5.2 and AE1/AE3 [12]. Immunolabeling for CK7, CK19 and CK20 is generally negative.

Molecular Findings

Acinar cell carcinomas do not harbour the mutations commonly found in ductal adenocarcinomas (e.g., KRAS, SMAD4). Also, abnormalities in p16 expression are not detected and rarely show TP53 immunoreactivity; so, acinar cell carcinomas have a distinct molecular phenotype [13, 14]. These tumours have a mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene/β-catenin pathway with a genetic progression similar to colon cancer. The molecular changes found in acinar cell carcinomas are the loss of heterozygosity at p1, %q25 at the APC locus, 9p21 at the p16 locus, and 17p3 at the p53 locus.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis should include well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine neoplasms, solid pseudopapillary neoplasms, mixed acinar neoplasms and pancreatoblastomas. The entity most commonly confused is well-differentiated endocrine neoplasms. Although acinar cell carcinomas can show focal endocrine differentiation, they can be distinguished from well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine neoplasms by acinar formation, basally oriented nuclei, cytoplasmic granulations and single prominent nucleoli. A high mitotic rate also favours an acinar cell carcinoma, whereas a hyalinised stroma and a “salt and pepper” chromatin pattern favour a well-differentiated endocrine neoplasm. The presence of squamoid nests in pancreatoblastomas distinguishes them from acinar cell carcinomas. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms almost always arise in young women. Pseudopapillary formation, poor cohesion of the neoplastic cells, the absence of true lamina, expression of vimentin, CD10 and alpha-1 antitrypsin also favour pseudopapillary neoplasm. Distinguishing mixed acinar neoplasms from pure acinar cell carcinomas is rarely possible on the basis of routine histology alone and a comparative immunohistochemical labelling for acinar and endocrine markers is needed to determine the proportion of each cell type.

Predictive Factors, Spread, Metastases and Prognosis

Acinar cell carcinomas are highly aggressive neoplasms, with a median survival for patients with localised disease and metastatic disease of 38 and 14 months, respectively, and an overall 5-year survival rate of less than 10 %; but, this neoplasm is not quite as rapidly lethal as conventional ductal adenocarcinoma [3, 5, 11]. Approximately 50 % of patients have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, and more than half of the remaining patients develop metastatic disease following surgical resection of the primary tumour but it is not uncommon for patients with distant metastases to survive for 2–3 years. Most often, metastatic disease is found in regional lymph nodes and liver, although occasional patients develop distant metastases to lung, cervical lymph nodes and ovary. It is rare for the patients to present with distant metastases as the first manifestation of the disease. It has been suggested that acinar cell carcinomas occurring under the age of 20 may be less aggressive than their adult counterpart [3].

The most important prognostic factor is tumour stage, with patients lacking lymph node or distant metastases surviving longer. Patients with the lipase hypersecretion syndrome were shown to have a particularly short survival, because most of these patients had widespread metastatic disease. No specific grading system for acinar cell carcinomas has been proposed. No association between the extent of acinus formation and prognosis has been observed. Other factors that have been correlated with poor outcome include male gender, age over 60, and tumour size greater than 10 cm [15].

Staging

The staging of acinar cell carcinomas should follow the staging of carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas.

Treatment

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for patients with early stage acinar cell carcinoma. Since most of the acinar cell carcinomas are quite large at presentation, they may appear to be unresectable [16]. However, these neoplasms grow in an expansile fashion, rendering even some large carcinomas resectable; so, resection is recommended when feasible. Surgical management is not curative in the majority of patients but surgical resection seems to be the only available curative treatment of acinar cell carcinomas, the chances of total resection should be surveyed intensively in every case. There is a 72 % rate of recurrent disease among patients who undergo a surgical resection, a number of whom experienced distant metastasis as opposed to local recurrences. On multivariate analysis, age less than 65 years, well-differentiated tumours, and negative resection margins are independent prognostic factors for acinar cell carcinoma [15].

There are no clear treatment guidelines for patients in whom complete resection with curative intent is not possible. In general, half of the patients have advanced disease with either metastases or locally unresectable tumour at the time of diagnosis. In cases of unresectable tumour with presence of distant metastases, chemotherapy with or without radiation to the pancreas has been utilised. However, the knowledge of the efficiency of any neoadjuvant or adjuvant with radiation or chemotherapy for acinar cell carcinomas is limited as less data are available regarding the efficacy of systemic therapy in the management of these carcinomas, with the published experience to date limited to small case series or case reports. One of the largest single-institution study was published from the Memorial Sloan Kettering cancer centre in 2002 [5]; at that time, the reported experience with systemic chemotherapy for ACC was not promising and concluded that the high recurrence rate of acinar cell carcinoma indicated that micrometastasis are likely present at the time of surgery, making adjuvant therapy necessary. Acinar cell carcinomas are moderately chemoresponsive to agents that have activity in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal carcinoma. In the absence of prospective data to guide therapy, treatment strategies for ACC patients frequently incorporate chemotherapy agents known to have activity in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or colorectal cancer. For locally advanced or metastatic disease, chemotherapeutic agents used in the treatment of colorectal cancers may be effective in acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas due to the genetic alteration in the APC gene/β-catenin pathway noted in acinar cells of the pancreas. 5-FU is the most commonly agents. Others that have been used are gemcitabine, cisplatin, doxorubicin, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, docetaxel, capecitabine, 5-FU/leucovorin, erlotinib, sunitinib and sirolimus. If the acinar cell carcinoma is unresectable, patient should be treated by 5-FU chemotherapy either with a neoadjuvant or palliative intention [17, 18]. Treated acinar cell carcinomas may show histologic changes including fibrosis and accumulation of histiocytes.

A recent study on 40 patients, published in 2011, observed the activity of combination chemotherapy in patients with metastatic ACCs and offers support for the use of gemcitabine or 5-FU-based combination chemotherapy incorporating irinotecan, a platinum analog, or docetaxel in patients with advanced disease [19]. This study reports a median survival time of 56.9 months for patients presenting with localised disease amenable to surgical resection. In this study, the median survival time of 19 months for patients with advanced disease reflects the less aggressive behaviour and greater chemosensitivity of acinar cell carcinomas than pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. The three drug combination offers the potential for significant activity in patients with ACC. The benefit of adjuvant therapy remains unproven. The conclusion of various studies is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conclusion of various studies

| Author | No. of cases (year) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Holen et al. [5] | 39 (2002) | The survival curves suggest a more aggressive cancer than pancreatic endocrine neoplasms but one that is less aggressive than ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. |

| Kitagami et al. [20] | 115 (2007) | A possibility of surgical resection should be pursued to achieve better prognosis. If ACC is unresectable or recurrent, chemotherapy is likely to prove useful. Multidisciplinary therapy centering on the role of surgery will need to be established. |

| Seth et al. [21] | 14 (2008) | Acinar cell carcinomas are rare, aggressive neoplasms that are difficult to diagnose and treat. Operative resection represents the best first-line treatment. These lesions have a better prognosis than the more common pancreatic adenocarcinomas. |

| Schmidt et al. [15] | 865 (2008) | ACC carries a better prognosis than DCC. Aggressive surgical resection with negative margins is associated with long-term survival in these more favourable pancreatic cancers. |

| Wisnoski et al. [22] | 672 (2008) | ACC is a more indolent disease than PA. The long-term survival for patients with ACC is significantly better when compared to the long-term survival of patients with PA. |

| Matos et al. [23] | 17 (2009) | Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas is rare and appears to have a presentation and outcome distinct from the more common pancreatic DCA |

| Lee et al. [24] | 29 (2010) | In Korea, the clinical features of ACC include young age, large size, tail location and non-specific tumour markers. Surgery should be actively performed in the treatment of ACC regardless of size |

| Hartwig et al. [25] | 17 (2011) | ACC of the pancreas is a relatively rare tumour entity for which resection may result in long-term survival even in limited metastatic disease |

| Butturini et al. [26] | 9 (2011) | ACC represents a rare solid tumour of the pancreas. Prognosis is dismal, although, compared to the more common ductal adenocarcinoma, survival appears to be longer. Patients with metastatic disease might benefit from aggressive multimodality treatments. |

| Lowery et al. [19] | 10 (2011) | ACC is moderately chemoresponsive to agents that have activity in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal carcinoma. A potential association between germ line mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes and ACC warrants further evaluation. |

ACC acinar cell carcinoma, PA pancreatic adenocarcinoma, DCC ductal cell carcinoma, DCA ductal cell adeno carcinoma

Conclusion

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma is a rare neoplasm and has been considered a cancer with poor prognosis due low resectability, high recurrence rate and frequent metastases but acinar cell carcinoma is a more indolent disease than pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Surgery should be performed in the treatment of these cancers regardless of size. The role of neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemoradiotherapy remains unproven.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Klimstra DS. Cell lineage in pancreatic neoplasms. In: Sarkar FH, Dugan MC, editors. Pancreatic cancer: advances in molecular pathology, diagnosis and clinical management. Natick: BIOtechniques Books; 1998. pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webb JN. Acinar cell neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas. J Clin Pathol. 1977;30:103–112. doi: 10.1136/jcp.30.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klimstra DS, Heffess CS, Oertel JE, Rosai J. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:815–837. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lack EE, Cassady JR, Levey R, Vawter GF. Tumors of the exocrine pancreas in children and adolescents. A clinical and pathologic study of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:319–327. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holen KD, Klimstra DS, Hummer A, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes from an institutional series of acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas and related tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4673–4678. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuerer H, Shim H, Pertsemlidis D, Unger P. Functioning pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 1997;20:101–107. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199702000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itoh T, Kishi K, Tojo M, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas with elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein levels: a case report and review of 28 cases reported in Japan. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1992;27:785–791. doi: 10.1007/BF02806533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuopio T, Ekfors TO, Nikkanen V, Nevalainen TJ. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Report of three cases. APMIS. 1995;103:69–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishihara A, Sanda T, Takanari H, et al. Elastase-1-secreting acinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas. A cytologic, electron microscopic and histochemical study. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabre A, Sauvanet A, Flejou JF, et al. Intraductalacinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:312–315. doi: 10.1007/s004280000342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoorens A, Lemoine NR, McLellan E, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. An analysis of cell lineage markers, p53 expression, and Ki-ras mutation. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:685–698. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ordonez NG. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:144–159. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longnecker DS. Molecular pathology of invasive carcinoma. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;880:74–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore PS, Beghelli S, Zamboni G, Scarpa A. Genetic abnormalities in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schimdt CM, Matos JM, Bentrem DJ, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas in the United States: prognostic factors and comparison to ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:278–286. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adam DT, Ralph HH, Syed ZA. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: clinical and cytomorphological characteristics. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:93–99. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Distler M, Ruckert F, Dittert DD, et al. Curative resection of primarily unresectable acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas after chemotherapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antoine M, Khitrik-palchuk M, Saif MW. Long term survival in a patient with acinar cell carcinoma of pancreas. A case report and review of literature. JOP. 2007;8:783–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowery MA, Klimstra DS, Shia J, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: new genetic and treatment insights into a rare malignancy. Oncologist. 2011;16:1714–1720. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitagami H, Kondo S, Hirano S, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: clinical analysis of 115 patients from pancreatic cancer registry of Japan pancreas society. Pancreas. 2007;35:42–46. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e31804bfbd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seth AK, Argani P, Campbell KA, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: an institutional series of resected patients and review of the current literature. Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1061–1067. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisnoski NC, Townsend CM, Jr, Nealon WH, et al. 672 patients with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a population-based comparison to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2008;144(2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matos JM, Schmidt CM, Turrini O, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: a multi-institutional study. Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(8):1495–1502. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0938-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JH, Lee KG, Park HK, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas in Korea—clinicopathologic analysis of 27 patients from Korean literature and 2 cases from our hospital. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55(4):245–251. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2010.55.4.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartwig W, Denneberg M, Bergmann F, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: is resection justified even in limited metastatic disease? Am J Surg. 2011;202(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butturini G, Pisano M, Scarpa A, et al. Aggressive approach to acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a single-institution experience and a literature review. Arch Surg. 2011;396(3):363–369. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]