Abstract

As the U.S. population ages, efficacious interventions are needed to manage pain and maintain physical function among older adults with osteoarthritis (OA). Skeletal muscle weakness is a primary contributory factor to pain and functional decline among persons with OA, thus interventions are needed that improve muscle strength. High-load resistance exercise is the best-known method of improving muscle strength; however high-compressive loads commonly induce significant joint pain among persons with OA. Thus interventions with low-compressive loads are needed which improve muscle strength while limiting joint stress. This study is investigating the potential of an innovative training paradigm, known as Kaatsu, for this purpose. Kaatsu involves performing low-load exercise while externally-applied compression partially restricts blood flow to the active skeletal muscle. The objective of this randomized, single-masked pilot trial is to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of chronic Kaatsu training for improving skeletal muscle strength and physical function among older adults. Participants aged ≥ 60 years with physical limitations and symptomatic knee OA will be randomly assigned to engage in a 3-month intervention of either (1) center-based, moderate-load resistance training, or (2) Kaatsu training matched for overall workload. Study dependent outcomes include the change in 1) knee extensor strength, 2) objective measures of physical function, and 3) subjective measures of physical function and pain. This study will provide novel information regarding the therapeutic potential of Kaatsu training while also informing about the long-term clinical viability of the paradigm by evaluating participant safety, discomfort, and willingness to continually engage in the intervention.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Aging, pain, exercise, disability, muscle strength, function

1. INTRODUCTION

The maintenance of one’s physical capabilities during older age is an essential part of healthy aging. The loss of functional abilities in advanced age is associated with not only the onset of disability and the loss of independence but also with increased rates of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.1–3 A decreased functional reserve also compromises one’s ability to respond to physiological stressors such as surgery.4 Notably, osteoarthritis (OA) is a primary risk factor for functional decline and the most common cause of disability among older adults.5–7 Estimates suggest that 30 to 50% of adults over the age of 65 years suffer from OA,8,9 and the proportion of affected individuals is expected to increase dramatically in coming years due to the aging of the population and increasing prevalence of OA.10,11 In particular, OA of the weight-bearing joints is the primary source of activity limitations – with OA of the knee being the most prevalent and most limiting.12–15 Accordingly, older adults with knee OA present greater difficulty in performing common physical tasks than non-afflicted peers.16,17 As a result, the development of interventions capable of reducing pain and maintaining physical function among these seniors with knee OA is an important public health priority.

Because skeletal muscle weakness is a primary contributory factor to the progression of functional decline among persons with OA,7,12 optimal interventions are those capable of improving muscle strength. High-load resistance exercise is the best-known method of improving strength; however joint pain resulting from high-compressive loads is a common barrier to this type of training.18,19 Accordingly, current recommendations include the performance of low- or moderate-load resistance exercise20,21 – despite the fact that these training paradigms are sub-optimal for enhancing muscle strength. Because of this limitation, alternative strategies are needed to enhance the efficacy of exercise training in improving physical function among older adults with OA. To date, inconsistencies in utilized methodology have limited the development of alternative exercise paradigms for reducing pain and improving function among older adults with OA.22,23

Due to the clinical contraindications to high joint loading in knee OA, it is critical to develop exercise paradigms capable of improving skeletal muscle strength while utilizing low loads. As we reviewed previously,24 Kaatsu training is an innovative approach for exactly this purpose. Kaatsu (a Japanese term meaning “added pressure”) training involves performing low-load resistance exercise while externally-applied compression mildly restricts blood flow to the active skeletal muscle. Mounting evidence collected over the last decade demonstrates that Kaatsu training serves as a potent stimulus for increasing skeletal muscle mass and strength.25–27 Because Kaatsu eases joint stress by avoiding high-compressive loads, we postulate that it has significant potential as a training modality for persons with knee OA. This study was designed to begin to test our central hypothesis that, among older adults with knee OA, KAATSU increases skeletal muscles strength while enhancing physical function and pain compared to moderate-intensity resistance training. The objective of this randomized pilot trial is to refine and finalize elements critical to conducting a future, fully-powered randomized, controlled trial to definitively test our central hypothesis.

2. STUDY DESIGN/METHODS

2.1 Overview

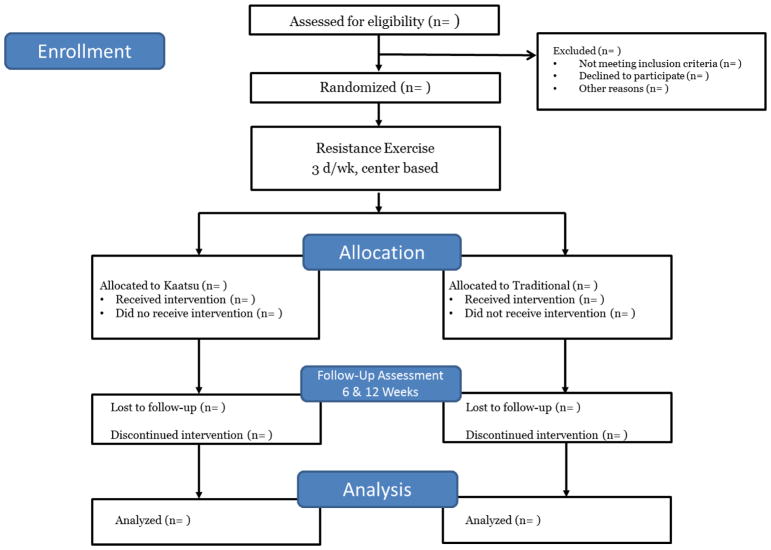

The study is a two-arm randomized, single-masked pilot trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Kaatsu, a novel exercise-based intervention, for improvement of muscle strength and physical function among in older adults with symptomatic knee OA. Following study entry, participants are randomly assigned to either Kaatsu or traditional isotonic resistance training for 12 weeks (Figure 1). Each condition consists of three center-based resistance training sessions per week (approximately 1 hour per session). Participant safety is overseen by a comprehensive study team – including the principal investigator, study physician, study staff, and an appointed Data and Safety Monitoring Board. The study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov prior to participant recruitment (NCT02132715) and all participants provide written informed consent based on documents approved by a university Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Overview of study design according to CONSORT format.

2.2. Participants

The study team is recruiting up to 72 (n = 36/group) functionally-limited older men and women with knee osteoarthritis. Eligible participants are persons ≥ 60 years of age with objective signs of functional limitations, do not participate in regular resistance training, and have OA of the knee defined by (1) radiolographic evidence of osteophytes, (2) pain classification > grade 0 on Graded Chronic Pain Scale,28 and bilateral standing anterior-posterior radiograph demonstrating Kellgren and Lawrence grade > 1 of the target knee. Persons with contraindications to tourniquet use, including those with peripheral vascular disease, SBP > 160 or < 100 mm Hg, DBP > 100 mm Hg, absolute contraindications to exercise training,29 or with other medical conditions that would preclude safe participation are excluded.

2.3 Screening, randomization, and masking

Interested individuals initially complete a telephone pre-screening prior to an in-person screening visit. Following the provision of informed consent, initial screening procedures include a review of medical history, physical activity habits, medication use, the Mini-mental State Exam30 to ensure participants have normal cognitive function (MMSE ≥ 24). Following these procedures, the 400 m walk test31 and Short Physical Performance Battery32 (walking speed < 1.2 m/sec or SPPB ≤10) are performed (as evidence of functional limitations) as well as a medical exam including assessment of OA-related symptoms.

If all study entry criteria are met, participants return to the clinic for baseline assessments prior to randomization. The study has a single-masked design, an accepted procedure for exercise-based studies as indicated by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Group,33,34 where the study staff conducting assessments are masked to the intervention assignment. To ensure masking of the assessment staff to intervention assignment, the randomization procedures are performed by staff not involved in the assessments. To enhance masking of the assessor, participants are asked not to disclose their assigned group and not to talk about their interventions during the testing sessions. Maintenance of staff blinding is facilitated by the fact that study interventions and assessments occur in separate physical locations. Placards are also placed in clinic rooms to remind participants not to tell assessors their group assignment. Intervention groups are also conducted at different times to prevent contamination bias between groups.

2.4 Assessments

2.4.1 Skeletal muscle strength

Maintenance of skeletal muscle strength, particularly of the knee extensor muscles, is a critical factor in the preservation of function among older adults with OA. Unilateral isokinetic strength of the knee extensors of the affected limb is be assessed by dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems, New York, NY) as published previously.35,36 The affected limb is operationalized as the limb with the OA which qualified for the study. Should both knees be affected by qualified OA, the limb which the participant reports as more painful is used. A note of the limb’s dominance (i.e. dominant or non-dominant) is made for potential consideration in the interpretation of study analyses.

2.4.2 Walking speed

Walking speed is a key predictor of health and survival in older adults.2,4,37 Participants walk at their usual pace over 10 laps of a 40 m course. Participants are allowed to use walking aids (e.g. cane, walker) but not the assistance of another person. The reliability of the 400 m walk test is excellent – with an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) above 0.9.38

2.4.3 Lower-extremity function

The SPPB is based on a timed short distance walk, repeated chair stands and balance test. This test is reliable39 and valid for predicting institutionalization, hospital admission, mortality and disability.40–43 Each task is scored by the research coordinator from 0 to 4, with 4 indicating best level of performance and 0 the inability to complete the test. A summary score (0–12) is then calculated.

2.4.4 Self-assessed physical function

Self-assessed functional status is documented using the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument.44,45 The instrument includes 16 tasks representing a broad range of disability indicators that assesses both frequency of doing a task and perceived limitation. The instrument uses a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of function. The scale has strong concurrent and predictive validity with physical performance.46

2.4.5 Self-assessed health status (WOMAC)

The WOMAC is a multidimensional, self-administered functional-health status instrument for patients with lower limb OA.47 Each of the knee pain questions of the WOMAC pain subscale are self-assessed by a 10 cm visual analogue scale with terminal descriptors (anchors of 0 cm = no pain; 10 cm = worst possible pain). The WOMAC has demonstrated validity as well as sensitivity to treatment effects in patients with knee pain.48,49

2.5 Interventions

Each study arm employs a 3 days/week, center-based resistance exercise intervention. Following a brief warm-up, participants perform lower-body strength training followed by flexibility exercises and balance training to promote cool-down. Training is performed using standard isotonic resistance training equipment (Life Fitness, Schiller Park, IL). Participants in the traditional intervention perform lower-extremity exercises (leg press, leg extension, leg curl, and toe stands) at a load of 60% of one repetition maximum (1RM), according to exercise guidelines for seniors with OA.1, 50–52 In the Kaatsu condition, resistance exercises are performed at 20% of 1RM with external compression applied to the proximal thigh of each leg. Because the exercise load (i.e. 60% vs. 20%) differs between groups, exercises are performed to volitional failure to equate the total metabolic work performed by each group. Compression for the Kaatsu condition is applied according to published tourniquet guidelines53 and maintained by pneumatic cuffs (TD 312 calculating cuff inflator, Hokanson, Bellevue, WA) as published previously.54,55 Cuffs remain inflated during performance of each exercise (i.e. in-between sets) but are be deflated for rest periods between exercises. Cuff pressure is set according to the equation [pressure = 0.5 (systolic blood pressure) + 2(thigh circumference) + 5] developed according to prior Kaatsu- and tourniquet-related literature.56–58 Based on entry criteria for blood pressure and a wide range of thigh girths (i.e. 35–65 cm), we expect thigh cuff pressures within a range (125–215 mm Hg) previously shown to be safe and efficacious.24,59,60

2.6 Safety

Numerous safety procedures were put in place to ensure participant safety. For instance, potential adverse events for study related activities and interventions are explained to each participant by trained study personnel during the informed consent process. Participants are encouraged to notify study staff immediately if they have any adverse experiences that could be related to the study interventions. Adverse experiences are monitored by study coordinators in a blinded fashion at each study visit and as reported. Interventionists also monitor adverse events as they are reported as well as any potential events that occur during performance of the exercise intervention. Clinical blood tests (i.e. CBC, metabolic panel, coagulation markers) are performed at each clinic assessment visit (Table 1) and are utilized to monitor potential hematologic and metabolic abnormalities in response to the interventions. Near-infrared spectroscopy is also performed at each assessment visit (during isokinetic skeletal muscle testing) to evaluate lower-extremity tissue hemoglobin saturations.

Table 1.

Data collection summary by study visit

| Study Phase | Pre- randomization | Randomization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit description (FU=follow-up, CO= close-out) | Screen | Baseline | FU | CO |

| Visit number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Week number | −2 | 0 | 6 | 12 |

| Prepare for visit, schedule, track | x | x | x | x |

| Informed consent, review inclusion/exclusion criteria | x | |||

| Personal interview, medical history | x | |||

| Physical exam | x | |||

| SPPB | x | x | ||

| 400 m walk | x | x | x | |

| Randomization | x | |||

| Late-Life Disability Questionnaire | x | x | ||

| WOMAC questionnaire | x | x | ||

| Blood collection | x | x | x | |

| Body composition assessment (DEXA) | x | x | ||

| Muscle strength testing | x | x | x | |

| Assess adverse experiences | x | x | ||

2.7 Statistical analyses

The primary statistical analyses will follow an “intent-to-treat” model in which participants are grouped according to randomization assignment. Mixed effects models will be used to determine the relative effect of the intervention on study outcomes. Differences in mean outcome measures between intervention groups will be estimated with visit number and intervention group in the model adjusted for baseline outcome measure, age, and gender. Hypothesis tests for intervention effects at assessment visits will be performed using contrasts of the 6- and 12-week intervention means. Overall comparisons between groups for the outcome measure across follow-up visits will be obtained using a contrast to compare average effects. For missing data analysis, initial baseline characteristics of participants who do and do not have follow-up measures will be compared. Maximum likelihood will be used to obtain tests for fixed effects and account for the possibility that missing outcomes are dependent on either observed covariates or previously observed outcomes. Sensitivity of results to missing outcomes that may be dependent on unobserved outcomes will be investigated through multiple imputation or propensity scores. Caution will be taken in the interpretation of hypothesis tests as power is limited and the relatively small sample size may create an imbalance in pre-randomization covariates.61 This sample size will, however, provide for nominal estimation (using a 95% confidence interval) of the mean changes in dependent variables within each arm of the study which will facilitate planning of a larger, fully-powered trial.

DISCUSSION

Our long-term goal is to develop interventions that optimize the beneficial effects of exercise training on physical function among older adults with OA. Osteoarthritis is the most common cause of chronic disability among older adults,7 with knee OA being the most prevalent and most limiting.14,15 Skeletal muscle weakness resulting from knee OA has a profound negative impact on the physical function and health-related quality of life of older adults.12,13 Accordingly, older adults with knee OA present greater difficulty in performing functional activities than non-afflicted peers.16,17 The primary factor contributing to this decline in function is skeletal muscle weakness – a problem propagated by physical inactivity. Accordingly, regular physical exercise has been recommended as an integral part of managing pain and functional decline of older adults with OA.21 However, due to several challenges and limitations associated with traditional methods of improving muscle strength in this population, scientists have recently been evaluating the efficacy of alternative training paradigms for maintaining strength and physical function.62–64

Accordingly, we propose to evaluate the efficacy and long-term viability of Kaatsu exercise as such an alternative paradigm. The concept of exercising while restricting blood flow has been around for nearly 40-years, and was popularized in Japan in the mid-1980’s. Literally translated, Kaatsu means “muscle strength testing with the addition of pressure.” This paradigm utilizes a relatively simple approach that generally involves inflating a narrow compressive cuff (11–15 cm wide) around an appendicular limb. The compressive pressure varies between studies, but typically the cuff is inflated to a pressure greater than brachial systolic pressure. Notably, the compressive pressure experienced at the artery is attenuated as there is a disassociation between tourniquet pressure and underlying soft-tissue pressure.57 As such, cuff pressure occludes venous return and causes arterial blood flow to become turbulent and blood velocity is reduced distal to the cuff. Because Kaatsu eases joint stress by avoiding high-compressive loads, we believe that it has significant potential as a training modality for persons with lower-extremity OA. At least one recent study supports this hypothesis as Kaatsu improved skeletal muscle strength among middle aged women at risk for OA compared to traditional low-load training.65

Indeed, mounting evidence collected over the last decade demonstrates that Kaatsu training serves as a potent stimulus for increasing skeletal muscle mass and strength25–27 and muscular endurance.66,67 The observation that exercise performed with low mechanical loads seemingly opposes traditional dogma regarding processes of muscle adaptation and has been proposed as a potentially efficacious method of improving muscle strength among persons for which high-load resistance training is medically contraindicated or infeasible.24,68,69 Thus, we hypothesize that Kaatsu training will provide an efficacious alternative to high-load resistance training for improving skeletal muscle strength and overall physical function in older adults with knee OA. Such a finding, if confirmed in a fully-powered randomized trial, could have critical implications for the prescription of resistance exercise as a therapy for knee OA.

The study described here will provide important feasibility and early efficacy data regarding the benefits of Kaatsu in our target population. The study will also enable us to refine the study protocol and procedures prior to conducting a fully-powered trial. As such it should be noted that the study protocol may be modified during the trial to optimize study procedures (recruitment, safety, etc) based upon information obtained during the course of the trial. Due to this and other limitations (e.g. relatively small sample size; single site design), it will be important not to over-interpret the results of this pilot study. Nonetheless, this study will inform the design of an efficient and definitive full-scale trial to determine if Kaatsu is a feasible and efficacious rehabilitation intervention among our target population. If our hypothesis is correct, the findings could provide evidence augmenting standard practice of providing prescriptions for rehabilitation of OA among older adults.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all study participants and staff devoting their time and effort to the study. The study is funded by a grant from the National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (1R21AR065039) with support from the University of Florida Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (2P30AG028740).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shaw LJ, Olson MB, Kip K, et al. The value of estimated functional capacity in estimating outcome: Results from the NHBLI-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(3 Suppl):S36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305(1):50–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Naydeck BL, et al. Association of long-distance corridor walk performance with mortality, cardiovascular disease, mobility limitation, and disability. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2018–2026. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afilalo J, Eisenberg MJ, Morin JF, et al. Gait speed as an incremental predictor of mortality and major morbidity in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(20):1668–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochberg MC, Kasper J, Williamson J, Skinner A, Fried LP. The contribution of osteoarthritis to disability: Preliminary data from the women’s health and aging study. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1995;43:16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ling SM, Fried LP, Garrett ES, Fan MY, Rantanen T, Bathon JM. Knee osteoarthritis compromises early mobility function: The women’s health and aging study II. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(1):114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loeser RF. Age-related changes in the musculoskeletal system and the development of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):371–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the united states. part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1207–1213. doi: 10.1002/art.24021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):355–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hootman JM, Helmick CG. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):226–229. doi: 10.1002/art.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis MA, Ettinger WH, Neuhaus JM, Mallon KP. Knee osteoarthritis and physical functioning: Evidence from the NHANES I epidemiologic followup study. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(4):591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rejeski WJ, Shumaker S. Knee osteoarthritis and health-related quality of life. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(12):1441–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semanik PA, Chang RW, Dunlop DD. Aerobic activity in prevention and symptom control of osteoarthritis. PM R. 2012;4(5 Suppl):S37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Statistics regarding the prevalence of OA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jinks C, Jordan K, Croft P. Osteoarthritis as a public health problem: The impact of developing knee pain on physical function in adults living in the community: (KNEST 3) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(5):877–881. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gur H, Cakin N. Muscle mass, isokinetic torque, and functional capacity in women with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(10):1534–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leveille SG, Fried LP, McMullen W, Guralnik JM. Advancing the taxonomy of disability in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(1):86–93. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.1.m86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lees FD, Clarkr PG, Nigg CR, Newman P. Barriers to exercise behavior among older adults: A focus-group study. J Aging Phys Act. 2005;13(1):23–33. doi: 10.1123/japa.13.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ettinger WH, Jr, Burns R, Messier SP, et al. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. the fitness arthritis and seniors trial (FAST) JAMA. 1997;277(1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Geriatrics Society Panel on Exercise and Osteoarthritis. Exercise prescription for older adults with osteoarthritis pain: Consensus practice recommendations. A supplement to the AGS clinical practice guidelines on the management of chronic pain in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(6):808–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Focht BC. Effectiveness of exercise interventions in reducing pain symptoms among older adults with knee osteoarthritis: A review. J Aging Phys Act. 2006;14(2):212–235. doi: 10.1123/japa.14.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster NE, Dziedzic KS, van der Windt DA, Fritz JM, Hay EM. Research priorities for non-pharmacological therapies for common musculoskeletal problems: Nationally and internationally agreed recommendations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manini TM, Clark BC. Blood flow restricted exercise and skeletal muscle health. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2009;37(2):78–85. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e31819c2e5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karabulut M, Abe T, Sato Y, Bemben MG. The effects of low-intensity resistance training with vascular restriction on leg muscle strength in older men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(1):147–155. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takarada Y, Takazawa H, Sato Y, Takebayashi S, Tanaka Y, Ishii N. Effects of resistance exercise combined with moderate vascular occlusion on muscular function in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(6):2097–2106. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patterson SD, Ferguson RA. Increase in calf post-occlusive blood flow and strength following short-term resistance exercise training with blood flow restriction in young women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):1025–1033. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. 0304-3959(92)90154-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ACSM, editor. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 7. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. 0022-3956(75)90026-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang M, Cohen-Mansfield J, Ferrucci L, et al. Incidence of loss of ability to walk 400 meters in a functionally limited older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2094–2098. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P CONSORT Group. Methods and processes of the CONSORT group: Example of an extension for trials assessing nonpharmacologic treatments. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):W60–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buford TW, Cooke MB, Manini TM, Leeuwenburgh C, Willoughby DS. Effects of age and sedentary lifestyle on skeletal muscle NF-{kappa}B signaling in men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buford TW, Cooke MB, Redd LL, Hudson GM, Shelmadine BD, Willoughby DS. Protease supplementation improves muscle function after eccentric exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a518f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dumurgier J, Elbaz A, Ducimetiere P, Tavernier B, Alperovitch A, Tzourio C. Slow walking speed and cardiovascular death in well functioning older adults: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rolland YM, Cesari M, Miller ME, Penninx BW, Atkinson HH, Pahor M. Reliability of the 400-m usual-pace walk test as an assessment of mobility limitation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(6):972–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostir GV, Volpato S, Fried LP, Chaves P, Guralnik JM Women’s Health and Aging Study. Reliability and sensitivity to change assessed for a summary measure of lower body function: Results from the women’s health and aging study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):916–921. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Penninx BW, Ferrucci L, Leveille SG, Rantanen T, Pahor M, Guralnik JM. Lower extremity performance in nondisabled older persons as a predictor of subsequent hospitalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(11):M691–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.m691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perkowski LC, Stroup-Benham CA, Markides KS, et al. Lower-extremity functioning in older mexican americans and its association with medical problems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(4):411–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: Consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(4):M221–31. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jette AM, Haley SM, Coster WJ, et al. Late life function and disability instrument: I. development and evaluation of the disability component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(4):M209–16. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.4.m209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haley SM, Jette AM, Coster WJ, et al. Late life function and disability instrument: II. development and evaluation of the function component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(4):M217–22. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.4.m217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sayers SP, Jette AM, Haley SM, Heeren TC, Guralnik JM, Fielding RA. Validation of the late-life function and disability instrument. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1554–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garratt AM, Brealey S, Gillespie WJ DAMASK Trial Team. Patient-assessed health instruments for the knee: A structured review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(11):1414–1423. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Topp R, Woolley S, Hornyak J, 3rd, Khuder S, Kahaleh B. The effect of dynamic versus isometric resistance training on pain and functioning among adults with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(9):1187–1195. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American College of Sports Medicine. Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, et al. American college of sports medicine position stand. exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(7):1510–1530. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the american college of sports medicine and the american heart association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1435–1445. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616aa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the american college of sports medicine and the american heart association. Circulation. 2007;116(9):1094–1105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klenerman L. The tourniquet manual: Principles and practice. London: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manini TM, Vincent KR, Leeuwenburgh CL, et al. Myogenic and proteolytic mRNA expression following blood flow restricted exercise. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2011;201(2):255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02172.x;10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larkin KA, Macneil RG, Dirain M, Sandesara B, Manini TM, Buford TW. Blood flow restriction enhances post-resistance exercise angiogenic gene expression. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182625928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Roekel HE, Thurston AJ. Tourniquet pressure: The effect of limb circumference and systolic blood pressure. J Hand Surg Br. 1985;10(2):142–144. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(85)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaw JA, Murray DG. The relationship between tourniquet pressure and underlying soft-tissue pressure in the thigh. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(8):1148–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Loenneke JP, Fahs CA, Rossow LM, et al. Effects of cuff width on arterial occlusion: Implications for blood flow restricted exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(8):2903–2912. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2266-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loenneke JP, Wilson JM, Wilson GJ, Pujol TJ, Bemben MG. Potential safety issues with blood flow restriction training. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(4):510–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01290.x;10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karabulut M, McCarron J, Abe T, Sato Y, Bemben M. The effects of different initial restrictive pressures used to reduce blood flow and thigh composition on tissue oxygenation of the quadriceps. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(9):951–958. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.572992;10.1080/02640414.2011.572992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: Recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10(2):307–312. doi: 10.1111/j.2002.384.doc.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoeksma HL, Dekker J, Ronday HK, et al. Comparison of manual therapy and exercise therapy in osteoarthritis of the hip: A randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(5):722–729. doi: 10.1002/art.20685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Talbot LA, Gaines JM, Ling SM, Metter EJ. A home-based protocol of electrical muscle stimulation for quadriceps muscle strength in older adults with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(7):1571–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pisters MF, Veenhof C, de Bakker DH, Schellevis FG, Dekker J. Behavioural graded activity results in better exercise adherence and more physical activity than usual care in people with osteoarthritis: A cluster-randomised trial. J Physiother. 2010;56(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/s1836-9553(10)70053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Segal NA, Williams GN, Davis MC, Wallace RB, Mikesky AE. Efficacy of blood flow-restricted, low-load resistance training in women with risk factors for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. PM R. 2015;7(4):376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kacin A, Strazar K. Frequent low-load ischemic resistance exercise to failure enhances muscle oxygen delivery and endurance capacity. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(6):e231–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01260.x;10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sumide T, Sakuraba K, Sawaki K, Ohmura H, Tamura Y. Effect of resistance exercise training combined with relatively low vascular occlusion. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Loenneke JP, Pujol TJ. KAATSU: Rationale for application in astronauts. Hippokratia. 2010;14(3):224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pillard F, Laoudj-Chenivesse D, Carnac G, et al. Physical activity and sarcopenia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(3):449–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2011.03.009;10.1016/j.cger.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]