1. Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders, affecting approximately 5.29% of the population worldwide (Polanczyk, Willcutt, Salum, Kieling, & Rohde, 2014). ADHD is characterized by elevated and persistent levels of inattention, locomotor activity, and impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The construct of impulsivity encompasses a wide range of phenomena (Evenden, 1999; Winstanley et al., 2006; Mitchell and Potenza, 2014; Sharma et al., 2013). The variety of impulsivity that characterizes ADHD is often described as a deficit in “behavioral inhibition” (Barkley, 1997; Wodka et al., 2007; Evenden, 1999) and “response inhibition capacity” (RIC; Chambers, Garavan, & Bellgrove, 2009). RIC, which is the focus of this paper, is the relatively stable ability to withhold an instrumentally reinforced response (e.g., withholding playing behavior in the classroom, or refusing an available but forbidden treat).

Research on the neurobiological substrate of RIC is greatly aided by animal models of ADHD, and by validated procedures to assess RIC in these models. Various genetic and lesion models of ADHD have been proposed (Russell, 2011), with most attention focused on the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR; Russell, Sagvolden, & Johansen, 2005; Sagvolden et al., 1992; Miller, Pomerleau, Huettl, Russell, Gerhardt & Glaser, 2012; Russell, 2002, 2003; Russell, Allie & Wiggins, 2000). Also, various methods for assessing RIC have been proposed, including the 5-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT; e.g., Robinson, Eagle, Economidou, Theobald, Mar, Murphy, Robbins & Dalley 2009), the differential reinforcement of low rates schedule (DRL; e.g., Stewart, Sargent, Reihman, Gump, Lonky, Darvill, Hicks & Pagano, 2006), and the fixed consecutive number schedule (FCN; e.g., Lovic et al., 2011; Evenden, 1998).

Although there is no published systematic review of RIC tasks, a succinct review shows various limitations and information gaps regarding their validity as methods to assess RIC. In particular, many of these tasks do not provide RIC indices that respond appropriately to key pharmacological treatments and that are robust against confounding factors, such as motivation. Moreover, there is no published information on the reliability of these indices. The purpose of this paper is to examine a RIC task that appears to address the limitations of extant methods, the fixed minimum interval schedule (FMI; Mechner & Guevrekian, 1962).

Pharmacological treatments that enhance RIC in humans do not reliably elevate RIC indices in 5-CSRTT (Bizarro et al., 2004; Navarra et al., 2008) and systematically lower them in DRL (Andrzejewski et al., 2014; Emmett-Oglesby, Taylor, & Dafter, 1980; Ferguson et al., 2007; Meaux & Chelonis, 2003; Orduña, Valencia-Torres, & Bouzas, 2009; Seiden, Andresen, & MacPhail, 1979). These findings suggest a reduced sensitivity of the 5-CSRTT and the DRL tasks to RIC-enhancing drug treatments. In contrast, RIC indices drawn from the FCN and the FMI tasks are elevated by appropriate pharmacological treatments (Evenden & Ko, 2005; Rivalan et al., 2007; Hill et al., 2012).

Moreover, changes in motivation appear to influence RIC indices in 5-CSRTT (Bizarro & Stolerman, 2003) and in DRL (Conrad, Sidman & Herrnstein, 1958; Holz & Azrin, 1963; Tanno, Kurashima & Watanabe, 2011; Beer & Trumble, 1965; Doughty & Richards, 2002; Kirshenbaum, Brown, Hughes, & Doughty, 2008). These findings suggest a reduced specificity of the 5-CSRTT and the DRL tasks to changes in RIC. In contrast, RIC indices drawn from the FCN and the FMI tasks appear to be robust against changes in motivation (Mechner & Guevrekian, 2007; Mazur et al., 2014).

Motivation is a particularly key confounding factor that is easily overlooked. This is because, at face value, motivation appears to be tightly related to RIC. For instance, if playing becomes more valuable to a child because her best friend is present, it should also become more difficult for the child to withhold playing. Nonetheless, as a trait capacity, RIC is independent of changes in motivation. That is, a child with lower RIC will be less likely to withhold playing, but that does not mean that the presence of her best friend reduces RIC. It is because of the trait-like nature of RIC that valid indices are expected to be reliable—they should be highly correlated across similar tests at different time points. No test has been conducted yet on the reliability of any animal RIC task.

The FCN and the FMI tasks appear to be best candidate RIC tasks from those currently available. The present study focuses on validating only the FMI task because of some potentially important differences with respect to FCN. First, the FMI is a time-based task: it requires animals to withhold a response for a fixed amount of time. Rats readily learn the temporal relation between stimuli (Bizot, 1997; Gibbon, 1977; Meck & Church, 1983; Staddon & Higa, 1999), which makes the FMI a more practical task. Also, animal timing is a well-studied phenomenon (Ludvig, Conover, & Shizgal, 2007; MacEwen, College, & Killeen, 1991; Staddon & Higa, 1999), so FMI performance can be analyzed in light of extant theories of animal timing (Sanabria & Killeen, 2008). Finally, in procedural terms, the FMI involves only a small modification of the DRL task: in FMI the response that initiates the withholding interval is different from the one that terminates it, whereas in DRL they are the same. This similarity is important because DRL performance has been extensively studied in humans and animals (Gordon, 1979; Dickerson, Mayes, Calhoun, & Crowell, 2001; Stein & Flanagan, 1974; Sanabria & Killeen, 2008), and in humans it is associated with ADHD-related impulsivity (Dickerson et al., 2001; Gordon, 1979). Figure 1 provides a succinct description of the FMI task.

Figure 1.

Schematic description of the FMI schedule of reinforcement and parameters of the Temporal Regulation model of withholding performance. In the FMI schedule, trial onset is signaled by the insertion of a lever. The first lever press initiates an inter-response time (IRT) that terminates with a head entry into the food hopper. IRTs longer than a programmed interval t are reinforced intermittently according to a conjunctive variable-interval (VI) 90-s schedule (for details, see Methods section). The Temporal Regulation model characterizes IRTs as sampled from a mixture of a gamma distribution (with mean μ and standard deviation σ) and an exponential distribution (with mean = standard deviation K). The model further characterizes μ as a linear function of t; the slope of that function, θ, serves as index of response inhibition capacity (RIC; for details see Temporal Regulation model section).

The FMI task was examined in two experiments. Experiment 1 tested whether the FMI-derived index of RIC is sensitive to the withholding requirement, is robust against a pre-feeding manipulation, is reliable, and does not correlate significantly with factors not associated with RIC. Experiment 2 further evaluated the reliability of the FMI task, and extended the test of its robustness against changes in motivation to two other manipulations: changing the rate of reinforcement and changing the magnitude of reinforcement.

2. Experiment 1

1.1. Animals

Ten experimentally-naïve male Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River, Hollister, California). Rats arrived on post-natal day (PND) 60 and were immediately pair-housed in a colony room with a 12:12-h day:night cycle, with lights on at 1900 h. Upon arrival food was available ad libitum in the homecage, but was gradually reduced to 1 hr daily access provided in the afternoon, a minimum of 20.5 h before the scheduled experiment on the following day. Water was always available ad libitum in the homecage. Each homecage contained two nylon bones (Bio-Serv model # K3580) that were replaced weekly. All experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

1.2. Apparatus

Experiments were conducted in 10 MED Associates (St. Albans, VT) modular test chambers (3 were 305 mm long, 241 mm wide, and 210 mm high; 7 were 305 mm long, 241 mm wide, and 292 mm high), each enclosed in a sound- and light-attenuating box equipped with a ventilation fan. The front and back walls and the ceiling of the test chambers were made of Plexiglas; the front wall was hinged and served as a door to the chamber. One of the two aluminum side panels served as a test panel. The floor consisted of 5-mm steel rods spaced 16 mm apart and positioned 36 mm above a catch pan. A square opening (51 mm each side) located 15 mm above the floor and centered on the test panel provided access to a food hopper (MED Associates, ENV-200-R2M). One 45-mg sucrose pellet (Test Diet, Richmond, IN) was delivered to the hopper with each activation of the dispenser. A multiple tone generator (MED Associates, ENV-223) was used to produce 3 kHz tones at approximately 75 dB through a speaker (MED Associates, ENV-224AM) centered on the top of the wall opposite to the test panel. Two retractable levers (ENV-112CM) were located on either side of the food hopper, but only one—the one closest to the door—was operational. Three-color light stimuli (ENV-222M) were mounted 35 mm above each lever; they could be illuminated yellow, green, and red. A force of approximately 0.2 N applied to the end of the lever was necessary for a lever press to be recorded. The ventilation fan mounted on the rear wall of the sound-attenuating chamber provided masked noise of approximately 60 dB. Experimental events were arranged via a Med-PC® interface connected to a PC controlled by Med-PC IV® software.

2.3 Procedure

Sessions were conducted daily, 7 days per week. Training started with one session of chamber habituation followed by one to two sessions of hopper training during which sucrose pellets were presented on a variable-time 15-s schedule. Once all rats were reliably eating all sucrose pellets, lever pressing for sucrose pellets was hand-shaped. After all rats were reliably lever pressing for sucrose pellets FMI sessions began.

Figure 1 provides a succinct description of the FMI task. In this task, subjects initiated each inter-response time (IRT) with a lever press (initial response), and were then required to withhold a head entry response into the hopper (terminal response) for a criterial time (t) for reinforcement to occur. An IRT was considered correct if it was equal or greater to the criterial time t, and incorrect if it was shorter than criterial time t. Correct IRTs were followed by an auditory cue, the retraction of the lever, and reinforcement arranged according to a conjunctive variable-interval (VI) schedule (see below). All trials were separated by a 10-s ITI.

2.4. Conjunctive VI schedule

During FMI testing, reinforcement was arranged on a VI schedule to reduce changes in reinforcement rates due to schedule and performance (Kirshenbaum et al., 2011; Sagvolden & Berger, 1996). At the beginning of a given session and after each reinforcer, an interval was selected without replacement from a 12-item Fleschler-Hoffman list (Fleshler & Hoffman, 1962). A stopwatch ran throughout the session; when it reached the randomly selected interval, reinforcement was programmed for the next correct IRT. If the interval elapsed within an IRT, that IRT was not reinforced; instead, reinforcement was set up for the next correct IRT.

The conjunctive VI schedule was introduced upon reliable performance in the first FMI condition (FMI 0.5-s). The VI schedule increased progressively over the course of multiple sessions from VI 9-s to 15, 30, 60 and 90-s. Progression was dependent upon reliable performance at each VI schedule, which was defined as less than 10% variation in the mean IRT across 3 consecutive sessions.

2.5. Manipulation of FMI schedule requirement

Rats were initially tested on an FMI 0.5-s schedule (with a conjunctive VI 90-s schedule) for a minimum of 10 sessions until stability was reached. Performance was deemed stable if the average group mean IRT did not vary more than 10% across 3 consecutive sessions and did not show any upward or downward trends. Once stability was achieved, subjects experienced one of the two experimental conditions (see Experimental conditions section) for one session, then returned to baseline conditions for a minimum of three sessions (or until stability was again met), and then experienced the second experimental condition. Having completed both experimental conditions under the FMI 0.5-s schedule, the target interval was changed to 6 s, 21 s, 6 s and finally 3 s again. Estimates of RIC were obtained from regressing the FMI performance of individual rats on FMI schedule requirement (see 2.7. Temporal Regulation model for details), thus requiring a within-subject manipulation of FMI schedule. The stability criterion and arrangement of experimental sessions used with the FMI 0.5-s schedule were repeated with each of the other FMI schedules. When the target interval for the current FMI schedule was greater than the previous one (as with the first 6-s schedule and the 21-s schedule), rats were trained up to the new target interval by increasing the criterial time t by 1.25% after each correct IRT, until the criterial time reached the target interval (either 6 or 21 s; this procedure required increasing the criterion from 0 s to 0.01 s). When the target interval for the current FMI schedule was shorter than the previous one (second 6-s schedule and 3-s schedule), the shorter FMI was imposed immediately. Sessions lasted for 1 h or until 150 reinforcers were obtained, whichever occurred first, except during the FMI 21-s testing when the session length was increased to 2 h to allow for more trials to be completed within each session.

2.6. Experimental Conditions

Two experimental conditions were implemented, Pre-feeding and Mediated, but only data from the Pre-feeding condition is reported here; data from the Mediated condition are not reported because no meaningful effect of this condition was observed on FMI performance. In the Pre-feeding condition, rats were provided an additional 1 hr ad libitum access to food in their homecage immediately prior to testing. In the Mediated condition (not reported), one Nylon bone from the homecage of each rat was placed in the operant chamber during testing. At the end of the session the nylon bone was returned to the homecage it came from. In each FMI schedule the order of experimental conditions were presented was randomly determined, except for the second FMI 6-s instantiation where experimental conditions were presented in the order opposite of how they were presented in the first instantiation.

2.7. Data Analysis

Latencies were defined as the intervals between trial onset and initial response (Figure 1); Post-R latencies were those of trials that followed a reinforced trial; Post-N were those of trials that followed non-reinforced trials, and the first trial in each session. IRTs were defined as the intervals separating initial and terminal responses. On each FMI schedule, data analysis was conducted on the latencies and IRTs the last 3–4 sessions prior to each experimental condition (Baseline sessions), and from Pre-feeding sessions. Rate of reinforcement (number of reinforcers per minute) was verified in these sessions. Two types of analysis were conducted: The first analysis was based on the comparison of descriptive statistics (median latencies, mean and standard deviation of IRTs); the second analysis was focused on the distribution of IRTs, based on estimates from the Temporal Regulation model of response-withholding performance (Sanabria & Killeen, 2008).

2.7. Temporal Regulation model

According to the Temporal Regulation model, only a proportion of IRTs are sensitive to the timing of reinforcement, and are thus labeled timed IRTs; the remainder are non-timed IRTs. Non-timed IRTs are terminated at random times with constant probability, and are therefore exponentially distributed. Timed IRTs, on the other hand, are terminated when the subjective time exceeds a response threshold, yielding a gamma distribution of timed IRTs (see Sanabria & Killeen, 2008, for details on the generation of timed IRTs). Therefore, IRTs are distributed according to this function:

| (1) |

In Equation 1, p(IRT = τ) is the probability of an IRT of duration τ; P is the probability that an IRT will be timed; Γ(N, c) is the gamma distribution of timed IRTs, with shape parameter N and scale parameter c; K is the mean non-timed IRT. These parameters are used to estimate the mean (μ = Nc) and standard deviation (σ = N0.5c) of timed IRTs (Figure 1).

In FMI and other response withholding tasks, impulsivity (i.e., low RIC) is expressed as low response thresholds, which yield short mean timed IRTs. The dispersion of timed IRTs, on the other hand, are indicative of the precision of subjective timing (Sanabria & Killeen, 2008). Moreover, it is well established that mean subjective time (μ) is a linear function of objective time (t; Gibbon & Church, 1981) and that variance in subjective time (σ2) is a linear function of the squared mean (μ2; Getty, 1975; Killeen & Weiss, 1987):

| (2) |

| (3) |

Equation 2 indicates that mean timed IRT is a linear function of criterial withholding interval t. The intercept, δ, is the mean duration of processes that are not sensitive to t (e.g., completing the lever-to-hopper motion). θ is proportional to the hypothetical response threshold that is correlated with impulsivity, and thus it serves as index of RIC (henceforth, for simplicity, we refer to θ as the response threshold).

Equation 3 indicates that as t approaches zero, the standard deviation of timed IRTs approaches β, which is the variability of processes not sensitive to t. As t increases, the standard deviation of timed IRTs becomes directly proportional to the mean timed IRT, consistent with the notion of scalar invariance of temporal judgments (Gibbon, 1977). Because of this proportionality, w serves as an index of timing imprecision.

Parameters θ, δ, w, and β were estimated for each individual rat from their FMI 3-s, 6-s, and 21-s data. Estimates of θ and w were not informed by FMI 0.5-s data because predictions of μ0.5 (that it is equal to δ) and of σ0.5 have weak empirical support. In FMI 0.5-s, performance is expected to depend primarily on the motoric demands of the task, which may result in distributions of IRTs that are not predictable from performance at longer withholding criteria. Therefore, in FMI 0.5-s, parameters P0.5, K0.5, μ0.5, and σ0.5 were estimated for each individual rat, but these estimates did not contribute to the estimation of θ or w. Instead, μ0.5 and σ0.5 were compared against predictions from Equations 2 and 3 fitted to FMI 3-s, 6-s, and 21-s data.

Note also that estimates of parameters P3, P6, P21, K3, K6, and K21 are not constrained by Equations 2 and 3. This is because there is no principled constraint to be applied to these estimates, and their psychological interpretation is ambiguous. Instead, changes in mean estimates of P and K across FMI schedules and conditions is reported, aiming at providing preliminary evidence in support of an interpretation of these parameters.

Collinearity among parameters θ, δ, w, β, P3, P6, and P21 was evaluated by determining the significance of correlations between estimates of these parameters in individual rats. All parameter estimations were conducted using the method of maximum likelihood (Myung, 2003).

2.8. Inferential statistics

Descriptive statistics were compared to determine whether pre-feeding and withholding interval had a significant effect on median latencies and mean and standard deviation of IRTs, implementing a 2 (Baseline vs. Pre-feeding) x 4 (FMI 0.5-s vs. 3-s vs. 6-s vs. 21-s) within-subject ANOVA on log-transformed dependent measures. Log transformation was implemented to address expected issues of non-normality and of proportionality of error to dependent measure, derived from Equations 1–3. When sphericity could not be assumed according to Mauchly’s test, a Huynh-Feldt correction was implemented. Significant interaction effects were followed up with 2-tail t-tests. Significant effects involving the schedule factor were followed up with comparisons between consecutive levels of this factor (i.e., FMI 0.5-s vs. 3-s, 3-s vs. 6-s, and 6-s vs. 21-s).

Reliability of the descriptive statistics was determined by comparing Baseline and Pre-feeding latencies and IRTs across instantiations of the FMI 6-s schedule. These comparisons involved testing the significance of the correlation of log-transformed dependent measures and of the difference between log-transformed dependent measures across instantiations of the same training conditions. Significant correlations coupled with non-significant differences were indicative of reliability.

The effects of pre-feeding was also evaluated on estimates of RIC (θ) and temporal imprecision (w). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) were drawn around the difference in parameter estimates between Baseline and Pre-feeding conditions. CIs that did not envelop zero were deemed significant. Reliability of the mean and standard deviation of timed IRTs (μt and σt) were determined by the correlation of and difference between these estimates across Baseline sessions preceding different experimental conditions in the same FMI schedule, and across Baseline and Pre-feeding sessions in each instantiation of the FMI 6-s schedule.

The criterion of significance for all the analyses was α = 0.05, except for the correlation between estimates of Temporal Regulation parameters. Because the correlation matrix of these parameters included 42 correlations, an α = 0.05 criterion would result in many false positives. Instead, for our test of collinearity, the criterion of significance was established at α = 0.01.

2. Results

One rat developed seizures during testing and therefore its data were excluded from all analyses.

3.1. Rate of reinforcement

In Baseline sessions, mean rate of reinforcement was virtually constant in FMI 0.5-s, 3-s, and 6-s (0.34–0.37 reinforcers/min), and declined in FMI 21-s (0.16 reinforcers/min). In Pre-feeding sessions, however, mean rate of reinforcement progressively declined as FMI requirement increased, from 0.38 reinforcers/min in FMI 0.5-s to 0.11 reinforcers/min in FMI 21-s. A significant schedule x condition interaction effect on rate of reinforcement was found (F (3,24) = 4.68, p = 0.010). Paired samples t-tests showed that Pre-feeding significantly reduced reinforcements rates at the FMI 6-s (t (8) = 3.26, p = 0.012) and FMI 21-s (t (8) = 2.37, p = 0.045) schedules. These results suggest that the conjunctive VI 90-s schedule dampened the effect of FMI on rate of reinforcement, but pre-feeding effects on performance in longer schedules were too strong to be moderated by the conjunctive VI schedule.

3.2. Analysis of descriptive statistics 1: Differences in central tendency and dispersion measures

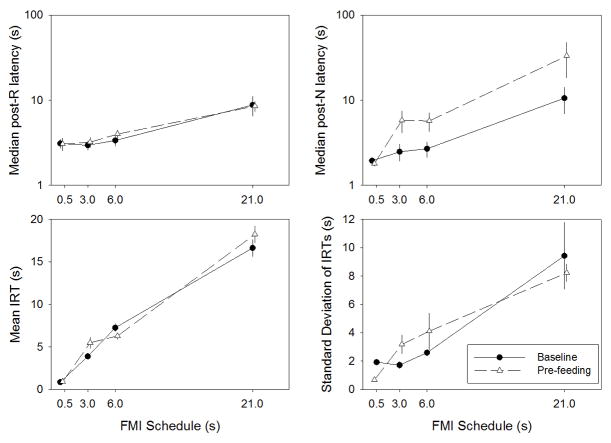

The top panels of Figure 2 show the mean (+/− SEM) of the median post-R (left panels) and post-N (right panels) latency. A significant schedule effect was observed on post-R latencies, F(1.92, 15.34) = 15.01, p < .001. Post hoc t-tests showed that post-R latencies increased significantly between FMI 3-s and FMI 6-s, t(8) = 4.16, p = .003, and between FMI 6-s than in FMI 21-s, t(8) = 3.80, p = .005. A significant schedule x level of deprivation effect was observed in post-N latencies, F(3, 24) = 14.12, p < .001. Post hoc t-tests showed that post-N latencies increased significantly between FMI 0.5-s and 3-s in the Pre-feeding condition, t(8) = 2.81, p = .023, and between FMI 6-s and 21-s in the Baseline condition, t(8) = 4.91, p = .001, and in the Pre-feeding condition, t(8) = 5.52, p = .001. At FMI 3-s, 6-s, and 21-s, post-N latencies increased significantly with pre-feeding, all t(8) > 3.66, all p < .007.

Figure 2.

Mean (+/− SEM) median post-R (A) and post-N (B) latencies, mean IRTs (C), and standard deviation of IRTs (D) in Baseline, Pre-feeding, and Mediated conditions across FMI schedules. FMI 6-s data was pooled across instantiations.

The bottom panels of Figure 2 show the mean (+/− SEM) of the mean (left panels) and standard deviation (right panels) of IRTs. A significant schedule x level of deprivation effect was observed on mean IRTs, F(3, 24) = 6.37, p = .002. Post hoc t-tests showed that, regardless of level of deprivation, longer FMI schedules always yielded significantly longer mean IRTs, all t(8) > 4.15, all p < .003. Pre-feeding significantly shortened FMI 0.5-s IRTs, t(8) = 6.07, p < .001, and lengthened FMI 3-s IRTs, t(8) = 2.62, p = .030. A significant schedule effect was observed on the SD of IRTs, F(1.63, 13.07) = 19.41, p < .001. Post hoc t-tests showed that IRT dispersion increased between FMI 0.5-s and 3-s, t(8) = 2.63, p = .030, and between FMI 6-s and FMI 21-s, t(8) = 3.43, p = .009.

3.3. Analysis of descriptive statistics 2: Reliability

The correlation between median latencies across instantiations of FMI 6-s was significantly positive in all conditions (mean r = .896) except for post-R latencies in the Pre-feeding condition (r = .073). Pairwise t-tests did not reveal significant differences in median latencies across instantiations of the FMI 6-s schedule (all p > .122). The correlations between mean IRTs (mean r = −.192) and standard deviations of IRTs (mean r = −.237) across instantiations of FMI 6-s were not significant in any condition. Pairwise t-tests did not reveal significant differences in mean or standard deviations of IRTs across instantiations of the FMI 6-s schedule (all p > .118). Taken together, these results suggest that, FMI latencies, but not their mean or standard deviation, were mostly resilient to an extended intervening change in FMI schedule. Nonetheless, mean descriptive statistics across animals did not vary significantly across instantiations of FMI 6-s.

3.4. Temporal Regulation model 1: Estimates of RIC and timing imprecision

Figure 3 shows the mean cumulative distribution of IRTs on each Baseline FMI schedule, along with the mean fit of the Temporal Regulation model (Equations 1–3) to these data. Overall, the model provided an adequate fit to IRT distributions. Figure 4 provides further evidence of goodness-of-fit of the model by comparing the observed mean and standard deviation of IRTs against predictions of the Temporal Regulation model.

Figure 3.

Mean cumulative probability distributions of IRTs in each FMI schedule under Baseline conditions. FMI 6 s data are pooled from both instantiations. The solid curves correspond to the fits of the Temporal Regulation model (Equations 1–3).

Figure 4.

Mean (+/− SEM) observed and predicted means (A) and standard deviations (B) of IRTs. Predicted values are estimated from the Temporal Regulation model (Equations 1–3).

Figure 5 shows mean (+/− SEM) estimates of Temporal Regulation parameters in each condition. Estimates of θ, the slope of mean timed IRTs regressed over criterial withholding time t, and β, the intercept of the SD of timed IRTs regressed over t, did not vary significantly across conditions. In contrast, estimates of δ, the intercept of timed IRTs regressed over t, and w, the slope of the SD of timed IRTs regressed over t, increased significantly with pre-feeding.

Figure 5.

Mean (+/− SEM) estimates of Temporal Regulation model parameters θ (A), δ (B), w (C), and β (D) in Baseline, Pre-feeding, and Mediated conditions. * Significant difference, p < .05.

Figure 6 shows estimates of Pt, the proportion of timed IRTs, as a function of t. Estimates of Pt were generally above .800, and appear to be an inverted-U function of the withholding interval. Relative to baseline, P0.5 increased significantly with pre-feeding, from .738 to .801. The high estimates of Pt mean that non-timed IRTs, with mean and standard deviation = K, only contributed 5–30% of the overall distribution of IRTs. When weighed by 1 − P, estimates of K show an approximate proportionality with t, growing from about K0.5 = 1.9 s to about K21 = 11.3 s.

Figure 6.

Mean (+/− SEM) estimates of Temporal Regulation model parameter P in Baseline, Pre-feeding, and Mediated conditions in each FMI schedule. FMI 6-s estimates were derived from pooled instantiations.

3.5. Temporal Regulation model 2: Analysis of collinearity

Table 1 is the correlation matrix of Temporal Regulation parameter estimates, arranged separately for each condition. Although several correlations were larger than expected by chance, only two correlations were significant and consistent in sign in both conditions. These were a negative correlation between θ and δ and a positive correlation between δ and β. The first correlation suggests that, as sensitivity to withholding requirement t increases, the length of processes not sensitive to t decreases. The second correlation suggests that, like the timed portion of IRTs, the standard deviation of processes not sensitive to t is proportional to their mean.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix of Temporal Regulation parameter estimates.

| Condition and Parameter | δ | w | β | P3 | P6 | P21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | θ | −0.798* | 0.052 | −0.372 | −0.149 | 0.598* | −0.363 |

| δ | 0.199 | 0.723* | 0.294 | −0.319 | 0.241 | ||

| w | −0.228 | 0.063 | 0.305 | −0.322 | |||

| β | 0.199 | −0.211 | 0.258 | ||||

| P3 | −0.022 | −0.041 | |||||

| P6 | −0.083 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Pre-feeding | θ | −0.841* | −0.169 | −0.374 | −0.266 | −0.526* | −0.222 |

| δ | 0.292 | 0.586* | 0.055 | 0.608 | 0.430 | ||

| w | −0.290 | −0.220 | −0.033 | 0.056 | |||

| β | 0.019 | 0.215 | 0.564* | ||||

| P3 | −0.167 | 0.321 | |||||

| P6 | −0.323 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Mediated | θ | −0.835* | 0.087 | −0.567* | −0.300 | 0.663* | −0.036 |

Note. Significant correlation, p < .01.

To probe into the possibility that these correlations are artifacts of regressing μ and σ over t, 20 runs of a 500-trial Monte Carlo simulation were conducted using the mean estimates of the distribution parameters of timed IRTs in each of three schedules, FMI 3-s, 6-s, and 21-s. Each trial sampled from a gamma distribution of timed IRTs corresponding to each schedule (Equation 1). Parameters θ, δ, and β were then estimated for each run. Consistent with empirical data, θ and δ were negatively correlated across runs (r = −.662). Contrary to empirical data, however, δ and β were also negatively correlated (r = −.556). These contrasting results suggest that the negative correlation between slope and intercept of mean timed IRTs is an artifact of the linear relation between θ and δ in Equation 1 coupled with the stochasticity of IRTs, which yields a regression-to-the-mean effect among uncorrelated variables (Barnett, van der Pols & Dobson, 2005). This explanation seems unlikely for the positive correlation between the intercept of mean and standard deviation of timed IRTs. Instead, this correlation suggests an empirical regularity akin to scalar invariance (Gibbon, 1977) for the portion of IRTs that is not sensitive to withholding requirement.

3.6. Temporal Regulation model 3: Reliability

Estimates of μ6 and σ6 were compared across instantiations of FMI 6-s, in each condition. No significant correlation was observed for either μ6 (mean r = −.200) or σ6 (mean r = −.084) on any condition.

3.7. Temporal Regulation model 4: Validation of FMI 0.5-s predictions

According to Equations 2 and 3, μ0.5 = δ and σ0.5 ≈ [(wδ)2 + β2]0.5. We contrasted these predictions, drawn from estimates of w, δ, and β in FMI 3-s, 6-s, and 21-s, with estimates of μ0.5 and σ0.5 drawn from FMI 0.5-s. Predictions of μ0.5 and σ0.5 from longer FMIs were generally higher than estimates from FMI 0.5-s, and no significant correlation was obtained between predictions and estimates.

3. Experiment 1 Discussion

Consistent with prior findings (Mazur, Wood-Isenberg, Watterson, & Sanabria, 2014; Mechner & Guevrekian, 1962), Experiment 1 shows that FMI latencies, particularly post-N, are substantially more sensitive than IRTs to a change in reinforcer efficacy. Latencies and IRTs, however, are sensitive to changes in withholding requirement. At longer FMI schedules, IRTs were longer and proportionally more variable. This pattern of change, along with a distribution of IRTs that tracked the withholding requirement (Figure 3), suggests that IRTs in FMI have a substantial timing component that is unaffected by changes in motivation.

The Temporal Regulation model of response withholding performance successfully identified the component of the distribution of IRTs, θ, that is sensitive to the timing requirements of FMI. This analysis suggests that even timed (i.e., gamma-distributed) IRTs have a time-insensitive component, δ, that probably reflects the motoric demands of completing the FMI schedule.

Both δ and the time-sensitive portion of IRT variability, w, increased with a reduction in reinforcer efficacy (Figure 7). These effects call into question interpretations of δ and w exclusively in terms of motoric and timing acuity. Nonetheless, a negative relation between timing acuity is well established in the timing literature (Bizo & White, 1995; MacEwen & Killeen, 1991; Morgan, Killeen & Fetterman, 1993; Raslear, Shurtleff & Simmons, 1992). In any case, θ was not significantly affected by acute pre-feeding manipulations, which supports θ as an index of RIC.

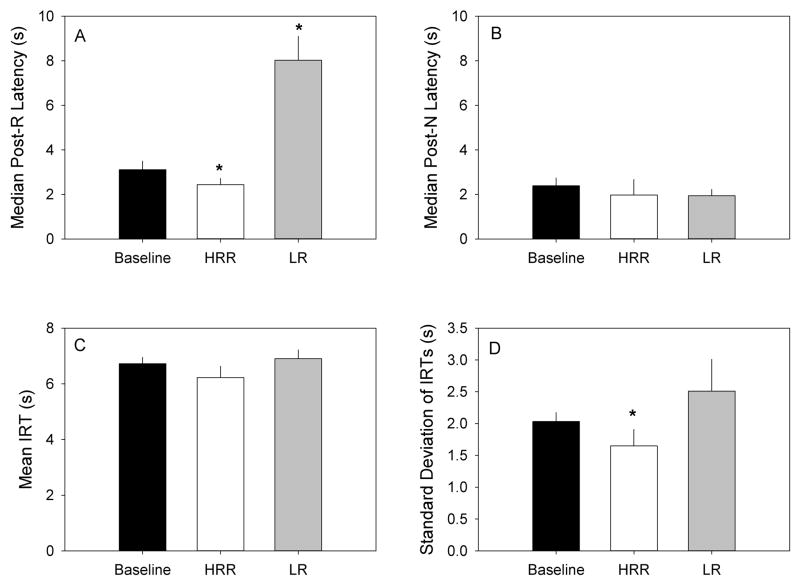

Figure 7.

Mean (+/− SEM) median post-R (A) and post-N (B) latencies, mean IRTs (C), and standard deviations of IRTs (D) in Baseline, HRR, and LR conditions. Baseline data is pooled from the two instantiations.

Systematic collinearity between some Temporal Regulation parameters was found. The negative correlation between θ and δ appears to be particularly problematic, as it involves the purported index of RIC. Nonetheless, this correlation seems to reflect an expected regression to the mean of timed IRTs across FMI schedules (Barnett, van der Pols & Dobson, 2005). A systematic collinearity was also observed between the time-insensitive portions of the mean and dispersion of timed IRTs—δ and β. The positive correlation between these parameters does not appear to be a regression artifact. Instead, it appears to capture an empirical association between processes indexed by these parameters that is absent in the model. The nature of this association is yet unclear. One possibility is that δ and β index a timing process that tracks some other unknown temporal regularity that does not covary with the withholding interval (e.g., the time it takes to move from the lever to the hopper). In that case, it is reasonable to expect proportionality between β and δ.

At the individual-subject level, median FMI 6-s latencies were recovered after at least 10 sessions on FMI 21-s, but IRT distribution parameters were not. This result suggests a learning component to IRTs that is absent in latencies, and that is affected by changes in FMI training. We sought to isolate this component using the Temporal Regulation model, but found no parameter of the distribution of timed IRTs that was not affected by the intervening FMI 21-s training.

Although the impact of pre-feeding and longer FMI schedules on rate of reinforcement was substantially mitigated by the conjunctive VI schedule, rate of reinforcement was not fully controlled. This means that changes in mean timed IRTs across FMI schedules may have been due not only to schedule demands, but also to changes in rate of reinforcement.

In the next experiment, rate and magnitude of reinforcement were explicitly manipulated to further test the hypothesis that latencies, and not timed IRTs, absorb the effect of these manipulations. Unlike Experiment 1, manipulations were kept in place for several consecutive sessions and only stable performance was analyzed. This approach was expected to minimize the likelihood of capturing transient changes in performance induced by acute manipulations.

4. Experiment 2

4.1. Subjects and Apparatus

The 9 subjects from Experiment 1 were included in this experiment, immediately after Experiment 1 was completed on PND 244. Housing and feeding conditions were identical to those described in Experiment 1. The same test chambers and reinforcers were used in this experiment.

4.2. Procedure

4.2.1. Baseline condition 1

Rats were trained on the FMI 6-s schedule, under conditions and stability criteria identical to those described as Baseline in Experiment 1, including the conjunctive VI 90-s schedule. After reaching stability, half of the rats were assigned to the Higher Rate of Reinforcement (HRR) condition and the other half to the Larger Reinforcer (LR) condition. Assignment was determined by performance during the last three Baseline sessions such that mean IRT and median latencies did not vary more than 0.5 s between groups.

5.2.2. Higher Rate of Reinforcement (HRR) condition

Reinforcement contingencies were similar to those in Baseline, except that the conjunctive VI schedule was reduced from 90 to 0 s. In this schedule, every correct response was reinforced. The HRR condition lasted for 11–13 sessions, and was followed by a reinstatement of Baseline conditions (see Baseline condition 2).

5.2.3. Larger Reinforcer (LR) condition

Reinforcement was arranged on a VI 90-s schedule just as during Baseline, but the reinforcer was increased from 1 to 4 sucrose pellets. The maximum number of trials per session was reduced from 150 to 37, so that the total number of reinforcers available per session was approximately equivalent to Baseline. The LR condition lasted for 11–13 sessions, and was followed by a reinstatement of Baseline conditions (see Baseline condition 2).

5.2.4. Baseline condition 2

Once stable performance was obtained under the HRR or LR conditions, whichever was experienced first, Baseline conditions (i.e., FMI 6-s with conjunctive VI 90-s reinforced with 1 pellet) were reinstated. Rats completed a minimum of 10 sessions and continued testing until stability criteria were met. Following stable performance, either HRR or LR conditions were implemented, whichever had not been experienced.

4.3. Data Analysis

Reinforcers per session, latencies and IRTs were collected from the last 5 sessions in each condition and used for analysis. The analysis of descriptive statistics involved the comparison of median latencies and mean and standard deviation of IRTs obtained under Baseline conditions (Baseline 1 and 2 data were pooled within subjects) against those obtained under HRR and LR conditions using t-tests and a significance criterion of α = .05. Reliability was established for median latencies and the mean and standard deviation of IRTs across Baseline conditions 1 and 2, following the procedure described in Experiment 1.

Mean, standard deviation, and proportion of timed IRTs (μ6, σ6, and P6) were estimated following the procedures described in Experiment 1. Baseline estimates were compared against HRR and LR estimates by computing 95% CI around the mean difference in estimates across conditions, and following analytical procedures described in Experiment 1. Reliability of these estimates was established by comparing them across Baseline conditions 1 and 2, following the procedure described in Experiment 1.

5.4. Results

5.4.1. Rate of reinforcement

Rate of reinforcement did not vary significantly between Baseline (mean = 0.37 reinforcers/min) and LR conditions (0.35 reinforcers/min). Rate of reinforcement increased substantially between Baseline and HRR conditions (1.41 reinforcers/min), t(8) = 5.72, p < .001.

5.4.2. Analysis of descriptive statistics 1: Differences in central tendency and dispersion measures

The top panels of Figure 7 show the mean (+/− SEM) of median post-R (left panel) and post-N (right panel) latencies. Post-R latencies declined significantly between Baseline and HRR conditions, t(8) = 2.98, p = .018, and increased significantly between Baseline and LR conditions, t(8) = 5.56, p = .001. Post-N latencies were not significantly affected by either experimental condition.

The bottom panels of Figure 7 show means (+/− SEM) of the mean (left panel) and standard deviation (right panel) of IRTs. No significant effect of condition was observed on mean IRTs. The standard deviation of IRTs was significantly reduced between Baseline and HRR conditions, t(8) = 2.73, p = .026.

5.4.3. Analysis of descriptive statistics 2: Reliability

Both types of latencies were significantly and positively correlated across Baseline conditions (post-R r = .942; post-N r = .856). The differences between latencies across Baseline conditions were not significant, all p > .560.

Mean IRTs, but not their standard deviations, were significantly and positively correlated across Baseline conditions (mean IRT r = .844; standard deviation of IRTs r = .526). Mean IRTs were systematically shorter in Baseline condition 1 (mean = 6.44 s) than 2 (mean = 7.00 s), t(8) = 3.32, p = .011. No significant difference between standard deviations across Baseline conditions was detected, p = .568.

5.4.4. Temporal Regulation model 1: Estimates of distribution parameters of timed IRTs

Figure 8 shows the mean cumulative distribution of IRTs on each condition, along with the mean fit of the Temporal Regulation model (Equation 1) to these data. The tight fit of the curves to the data suggests that the model provides an adequate description of performance.

Figure 8.

Mean cumulative probability distributions of IRTs in Baseline, HRR, and LR conditions. Baseline data are pooled from both instantiations. The solid curves correspond to the fits of the Temporal Regulation model (Equation 1).

Figure 9 shows mean (+/− SEM) estimates of the mean (μ6; left panel) and standard deviation (σ6; right panel) of timed IRTs. Mean timed IRTs did not change significantly between conditions. The standard deviation of timed IRTs declined significantly between Baseline and HRR conditions, but did not change significantly between Baseline and LR conditions. Estimates of P6 did not vary significantly between conditions; their mean estimates ranged from .942 to .959 across conditions. These high estimates of P6 suggest that K6 contributed to less than 6% of the distribution of IRTs, and were thus not further analyzed.

Figure 9.

Mean timed IRTs (A) and standard deviations of timed IRTs (B) across Baseline, HRR and LR conditions. * Significant difference, p < .05.

5.4.5. Temporal Regulation model 2: Analysis of collinearity

Table 2 is the correlation matrix of Temporal Regulation parameter estimates, separated by condition. The correlation between means and standard deviations of timed IRTs was positive and significant in all conditions; no other correlation was significant. To probe a potential relation of proportionality between means and standard deviations of timed IRTs, the ratio of each standard deviation to its corresponding mean—the coefficient of variation—was calculated (this is equivalent to w in Equation 3, if β = 0). If standard deviations are proportional to means, then the correlation between coefficients of variation and means would not be significant. Instead, however, these correlations were still positive and significant in Baseline and HRR conditions (r = .551 and .737, respectively), and positive but not significant in the LR condition (r = .381). This suggests that the relation between standard deviation and mean of timed IRTs is not of direct proportionality, but instead standard deviations rise faster as the mean increases.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of Temporal Regulation parameter estimates.

| Condition and Parameter | σ6 | P6 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | μ6 | .798* | −.007 |

| σ6 | .009 | ||

|

| |||

| HRR | μ6 | .904* | .186 |

| σ6 | .063 | ||

|

| |||

| LR | μ6 | .621* | −.106 |

| σ6 | .293 | ||

Note. Significant correlation, p < .01.

5.4.6. Temporal Regulation model 3: Reliability

Estimates of the mean (μ6) and standard deviation (σ6) of timed IRTs were compared across Baseline conditions 1 and 2. A significant correlation was observed between mean timed IRTs across Baseline conditions (r = .680); the difference between timed IRTs across Baseline conditions was not significant, t(8) = 2.19, p = .060. No significant correlation was observed between standard deviations of IRTs (r = .453).

5. Experiment 2 Discussion

Experiment 2 expands the validation test of the FMI schedule to two new experimental manipulations, rate of reinforcement and reinforcer magnitude. Experiment 2 shows that FMI latencies are substantially more sensitive to these manipulations than mean IRTs (Figure 7). More specifically, post-R latencies decreased with higher rates of reinforcement and increased with larger reinforcers. Whereas mean IRTs were not significantly affected by either manipulation, the standard deviation of IRTs declined with a higher rate of reinforcement. This pattern of effects on IRTs did not change substantially when timed IRTs were isolated (Figure 9). These findings replicate the main finding of Experiment 1 regarding IRTs: mean timed IRTs are robust against motivational manipulations, but the dispersion of IRTs is negatively related to motivation.

Although post-R latencies were sensitive to changes in rate of reinforcement and reinforcer magnitude, once these manipulations were discontinued latencies rebounded to pre-manipulation levels. Mean IRTs were correlated across Baseline conditions, but they showed a significant tendency to increase over instantiations. When timed IRTs were isolated, the correlation across baselines was just slightly reduced and the tendency to increase was no longer significant. This suggests that, like latencies, individual timed IRTs are robust to sustained changes in rate of reinforcement and reinforcer magnitude. In contrast, the standard deviation of IRTs, whether timed IRTs were isolated or not, did not reliably recover following these changes.

A systematic correlation was observed only between mean and standard deviation of timed IRTs. This is consistent with performance in other timing tasks (Wearden, 1985), and with Equation 3. That coefficients of variation were also positively correlated with mean timed IRTs suggests that the relation between the distribution parameters of timed IRTs is more complex than Equation 3 suggests. Timing research has reported similar deviations from proportionality (Bizo, Chu, Sanabria, & Killeen, 2006); these reports may provide further guidance for analyzing FMI performance.

6. General Discussion

The purpose of this study was to validate the FMI schedule of reinforcement as a behavioral paradigm to assess the ability of rodents to withhold an instrumentally-reinforced response (response inhibition capacity, or RIC). Such ability appears to be a central feature of the ADHD phenotype (Barkley, 1997). In particular, this study was aimed at determining whether the index of RIC derived from the FMI, θ, was robust against changes in level of deprivation, rate of reinforcement, and magnitude of reinforcement, and whether it recovered when identical experimental conditions were reinstated.

The present data confirmed that FMI schedules produce a mixture of gamma-distributed timed IRTs (74–95%) and exponentially-distributed non-timed IRTs. The parameter θ is the sensitivity of mean timed IRTs to changes in the target withholding time (Sanabria & Killeen, 2008). θ has often been estimated from single FMI schedules by dividing the mean timed IRT by the target time, in which case θ and mean timed IRT are directly proportional (Hill et al., 2012; Mazur et al., 2014; Mika et al., 2012; Watterson et al., in press). Nonetheless, Sanabria and Killeen (2008) also suggested estimating θ as the slope of a linear regression of mean timed IRTs over multiple target times (Equation 2). Estimated this way, θ was robust against changes in level of deprivation (Figure 5). Even when the mean timed IRT was estimated from a single FMI schedule, it was still robust against changes in rate of reinforcement and reinforcer magnitude (Figure 9). Moreover, even when timed and non-timed IRTs are not isolated, mean IRTs are robust against these manipulations (Figures 2 and 7; see also Mechner & Guevrekian, 1962). The effects of reinforcer manipulations were captured by other parameters of FMI performance, including latencies, the intercept of the regression of mean IRTs over target times (δ), and the dispersion of timed IRTs. The differential sensitivity of latencies, but not mean IRTs or θ to changes in reinforcer efficacy indicates that, unlike other methods of assessing RIC in rodents (Beer & Trumble, 1965; Bizarro & Stolerman, 2003; Conrad et al., 1958; Doughty & Richards, 2002; Holz & Azrin, 1963; Kirshenbaum et al., 2008; Tanno et al., 2011), the FMI schedule effectively dissociates incentive-motivational effects from inhibitory effects.

In Experiment 1, the conjunctive VI schedule dampened the effect of FMI requirement on rate of reinforcement. Nonetheless, this effect was still visible, particularly in pre-fed rats, whose rate of reinforcement dropped 3.5-fold between FMI 0.5-s and FMI 21-s. This justified a concern that changes in estimates of θ across FMI schedules were not only due to changes in withholding requirement, but also due to changes in rate of reinforcement. However, Experiment 2 demonstrated the resiliency of estimates of θ against a fourfold change in rate of reinforcement. Therefore, estimates of θ from Experiment 1 were more likely to be sensitive to FMI requirement than to rate of reinforcement. This finding also suggests that control of rate of reinforcement through complex procedures such as a conjunctive VI schedule may not be required to obtain reliable estimates of θ from FMI performance.

Although θ is sensitive to the FMI requirement, it should not be interpreted as an index of timing acuity. Sanabria, Thrailkill & Killeen’s (2009) model of timing informs the interpretation of θ. In this model, the target response occurs when subjective time exceeds a threshold. Changes in the speed of the internal clock are expected to disturb mean response times, but only transiently, because feedback is expected to recover baseline mean response times (Meck, 1996). Therefore, stable changes in mean response time without a change in the timed interval are not attributed to changes in subjective time; instead, they are attributed to changes in the response threshold, which are reflected in estimates of θ. In signal-detection terms, θ does not index the discriminability of the FMI requirement relative to other intervals; instead it indices the decision criterion for emitting a response given the perceived amount of time since the withholding interval was initiated.

Estimates of timed IRT dispersion, including w (Equation 3), are more adequate indices of timing acuity—they provide a more reliable index the discriminability of the FMI requirement relative to other intervals (cf., Rammsayer & Altenmüller, 2006). Unlike θ, estimates of timed IRT dispersion were sensitive to acute pre-feeding (Experiment 1) and to more long-term changes in rate of reinforcement (Experiment 2). In general, lower levels of motivation yielded more disperse timed IRTs. It is important to note that, because of the limited control that the conjunctive VI schedule exerted on rate of reinforcement, pre-feeding and rate-of-reinforcement effects were confounded in Experiment 1. It is therefore possible that effects observed on IRT dispersion may stem from a negative correlation between dispersion and rate of reinforcement. This negative relation between rate of reinforcement and timing acuity is well established in the timing literature (Bizo & White, 1995; MacEwen & Killeen, 1991; Morgan et al., 1993; Raslear et al., 1992). However, this relation does not appear to affect estimates of θ, which is consistent with the notion that timing acuity and RIC are dissociable.

Taken together, the present study supports θ, estimated from FMI performance, as a reliable index of RIC in rats. The use of θ, however, is not without limitations. Although individual estimates of mean timed IRTs across rats were resilient to prolonged changes in reinforcer efficacy (Experiment 2), they were not reliably recovered following a longer FMI schedule (Experiment 1). The latter effect suggests that θ is vulnerable to learning effects; further research may determine the extent of this vulnerability.

Despite its limitations, the FMI schedule of reinforcement appears to be a preferable method for assessing RIC. Alternative methods, such as 5-CSRTT and the DRL, are not sensitive to key pharmacological manipulations (Andrzejewski et al., 2014; Bizarro et al., 2004; Emmett-Oglesby et al., 1980; Ferguson et al., 2007; Meaux & Chelonis, 2003; Navarra et al., 2008; Orduña et al., 2009; Seiden et al., 1979) but are sensitive to confounding motivational manipulations (Bizarro & Stolerman, 2003; Conrad et al., 1958; Holz & Azrin, 1963; Tanno et al., 2011; Beer & Trumble, 1965; Doughty & Richards, 2002; Kirshenbaum et al., 2008). The present study and Hill et al. (2012) suggest that the FMI is not vulnerable to these problems. Moreover, the FMI appears to be at least as empirically and analytically parsimonious as alternative RIC-assessment methods. 5-CSRTT and pharmacologically-sensitive variations of the FCN schedule involve complex training protocols (Bari, Dalley & Robbins, 2008; Evenden & Ko, 2005). Analyses of DRL performance that isolate burst responding are also complex (Richards, Sabol & Seiden, 1993; Sanabria & Killeen, 2008). The complexities inherent to mathematical models of behavior, such as the Temporal Regulation model, may be discouraging, but they pay their way in precision, construct validity, and integration with a larger body of research—signal detection theory and timing, in the case of the Temporal Regulation model. Advancing these mathematical models with the guidance of theory will support further progress in RIC-assessing methods, akin to that observed in other varieties of self-control (e.g., Killeen, 2009; Logan, Cowan & Davis, 1984).

Highlights.

This study validates a novel method for testing response inhibition capacity in rats.

Fixed minimum interval (FMI) performance was compared across a range of conditions.

Inhibitory and motivational aspects of FMI performance were dissociated.

Results support empirical and analytic methods to assess RIC in animal models.

Acknowledgments

The present study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH094562) and by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Arizona State University. We thank Chris Fencl, Ryan J. Brackney, Carter W. Daniels, Raul Garcia, Jake Gilmour, Briana Martinez, Luis Lopez, Andrew Nye, Paulina Solis, and Cavan Winikates for support in data collection and analysis. Raul Garcia, Briana Martinez, and Luis Lopez were supported by the Western Alliance to Expand Student Opportunities (WAESO).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Watterson, Email: Elizabeth.Watterson@asu.edu.

Gabriel J. Mazur, Email: Gabriel.Mazur@asu.edu.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. 2013. p. 991. DSM-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejewski ME, Spencer RC, Harris RL, Feit EC, McKee BL, Berridge CW. The effects of clinically relevant doses of amphetamine and methylphenidate on signal detection and DRL in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Dowson JH, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Methylphenidate improves response inhibition in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:1465–1468. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00609-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. The application of the 5-choice serial reaction time task for the assessment of visual attentional processes and impulse control in rats. Nature Protocols. 2008;3(5):759–767. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(1):65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: What it is and how to deal with it. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34(1):215–220. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer B, Trumble G. Timing behavior as a function of amount of reinforcement. Psychonomic Science. 1965;2(1–12):71–72. doi: 10.3758/BF03343335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bizarro L, Stolerman IP. Attentional effects of nicotine and amphetamine in rats at different levels of motivation. Psychopharmacology. 2003;170(3):271–7. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizo LA, Chu JYM, Sanabria F, Killeen PR. The failure of Weber’s law in time perception and production. Behavioural Processes. 2006;71(2–3):201–10. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizo LA, White KG. Biasing the pacemaker in the behavioral theory of timing. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1995;64(2):225–235. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizot JC. Effects of psychoactive drugs on temporal discrimination in rats. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1997;8:293–308. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199708000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonstra AM, Kooij JJS, Oosterlaan J, Sergeant JA, Buitelaar JK. Does methylphenidate improve inhibition and other cognitive abilities in adults with childhood-onset ADHD? Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2005;27:278–298. doi: 10.1080/13803390490515757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, del Campo N, Dowson J, Müller U, Clark L, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Atomoxetine Improved Response Inhibition in Adults with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CD, Garavan H, Bellgrove MA. Insights into the neural basis of response inhibition from cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33(5):631–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad DG, Sidman M, Herrnstein RJ. The effects of deprivation upon temporally spaced responding. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1958;1(1):59–65. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1958.1-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Mar AC, Economidou D, Robbins TW. Neurobehavioral mechanisms of impulsivity: fronto-striatal systems and functional neurochemistry. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2008;90(2):250–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit H, Enggasser JL, Richards JB. Acute administration of d-amphetamine decreases impulsivity in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:813–825. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demurie E, Roeyers H, Baeyens D, Sonuga-Barke E. Temporal discounting of monetary rewards in children and adolescents with ADHD and autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Science. 2012;15:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson Mayes S, Calhoun SL, Crowell EW. Clinical validity and interpretation of the Gordon Diagnostic System in ADHD assessments. Child Neuropsychology: A Journal on Normal and Abnormal Development in Childhood and Adolescence. 2001;7(1):32–41. doi: 10.1076/chin.7.1.32.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty AH, Richards JB. Effects of reinforcer magnitude on responding under differential-reinforcement-of-low-rate schedules of rats and pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78(1):17–30. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle DM, Robbins TW. Inhibitory control in rats performing a stop-signal reaction-time task: effects of lesions of the medial striatum and d-amphetamine. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;117(6):1302–17. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmett-Oglesby MW, Taylor KE, Dafter RE. Differential effects of methylphenidate on signalled and non-signalled reinforcement. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1980;13:467–470. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Erkanli A, Conners CK, Klaric J, Costello JE, Angold A. Relations between Continuous Performance Test performance measures and ADHD behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31(5):543–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1025405216339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Johnson DE, Varia IM, Conners CK. Neuropsychological assessment of response inhibition in adults with ADHD. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2001;23(3):362–71. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.3.362.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. The pharmacology of impulsive behaviour in rats II: the effects of amphetamine, haloperidol, imipramine, chlordiazepoxide and other drugs on fixed consecutive number schedules (FCN 8 and FCN 32) Psychopharmacology. 1998;138:283–294. doi: 10.1007/s002130050673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146(4):348–61. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SA, Paule MG, Cada A, Fogle CM, Gray EP, Berry KJ. Baseline behavior, but not sensitivity to stimulant drugs, differs among spontaneously hypertensive, Wistar-Kyoto, and Sprague-Dawley rat strains. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2007;29(5):547–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleshler M, Hoffman HS. A progression for generating variable-interval schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1962;5:529–30. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getty DJ. Discrimination of short temporal intervals: A comparison of two models. Perception & Psychophysics. 1975;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.3758/BF03199358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J. Scalar expectancy theory and Weber’s law in animal timing. Psychological Review. 1977;84(3):279–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Church RM. Time left: Linear versus logarithmic subjective time. Journal of Experimental Psychology of Animal Behavior Processes. 1981;7(2):87–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. The assessment of impulsivity and mediating behaviors in hyperactive and nonhyperactive boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1979;7:317–326. doi: 10.1007/BF00916541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondin S. Timing and time perception: a review of recent behavioral and neuroscience findings and theoretical directions. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics. 2010;72:561–582. doi: 10.3758/APP.72.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondin S, Ouellet B, Roussel M-È. About optimal timing and stability of Weber fraction for duration discrimination. Acoustical Science and Technology. 2001;22(5):370–372. doi: 10.1250/ast.22.370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JC, Covarrubias P, Terry J, Sanabria F. The effect of methylphenidate and rearing environment on behavioral inhibition in adult male rats. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219(2):353–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2552-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz WC, Azrin NH. A comparison of several procedures for eliminating behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1963;6:399–406. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR. An additive-utility model of delay discounting. Psychology Review. 2009;116(3):602–619. doi: 10.1037/a0016414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR, Fetterman JG. A behavioral theory of timing. Psychological Review. 1988;95(2):274–95. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.95.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen PR, Weiss NA. Optimal timing and the Weber function. Psychological Review. 1987;94(4):455–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenbaum AP, Brown SJ, Hughes DM, Doughty AH. Differential-reinforcement-of-low-rate-schedule performance and nicotine administration: a systematic investigation of dose, dose-regimen, and schedule requirement. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2008;19(7):683–97. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328315ecbb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer TJ, Rilling M. Differential reinforcement of low rates: A selective critique. Psychological Bulletin. 1970;74(4):225–254. [Google Scholar]

- Laties VG, Weiss B, Clark RL, Reynolds MD. Overt “mediating” behavior during temporally spaced responding. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1965;8:107–116. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1965.8-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laties VG, Weiss B, Weiss AB. Further observations on overt “mediating” behavior and the discrimination of time. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1969;12(1):43–57. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Cowan WB, Davis KA. On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction time responses: A model and a method. Journal of Experimental Psychology of Human Perception and Performance. 1984;10(2):276–291. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovic V, Keen D, Fletcher PJ, Fleming AS. Early-life maternal separation and social isolation produce an increase in impulsive action but not impulsive choice. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2011;125(4):481–491. doi: 10.1037/a0024367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvig Ea, Conover K, Shizgal P. The Effects of Reinforcer Magnitude on Timing in Rats. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;87(2):201–218. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.38-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEwen D, Killeen PR. The effects of rate and amount of reinforcement on the speed of the pacemaker in pigeons’ timing behavior. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1991;19(2):164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur GJ, Wood-Isenberg G, Watterson E, Sanabria F. Detrimental effects of acute nicotine on the response-withholding performance of spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar Kyoto rats. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231(12):2471–82. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3412-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaux JB, Chelonis JJ. Time perception differences in children with and without ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Health Care: Official Publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners. 2003;17(2):64–71. doi: 10.1067/mph.2003.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechner F, Guevrekian L. Effects of deprivation upon counting and timing in rats. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1962;5(4):463–466. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH. Neuropharmacology of timing and time perception. Brain and Cognition. 1996;58(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Church RM. A mode control model of counting and timing processes. Journal of Experimental Psychology Animal Behavior Processes. 1983;9(3):320–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mika A, Mazur GJ, Hoffman AN, Talboom JS, Bimonte-Nelson HA, Sanabria F, Conrad CD. Chronic stress impairs prefrontal cortex-dependent response inhibition and spatial working memory. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;126(5):605–19. doi: 10.1037/a0029642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EM, Pomerleau F, Huettl P, Russell VA, Gerhardt GA, Glaser PEA. The spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar Kyoto rat models of ADHD exhibit sub-regional differences in dopamine release and uptake in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63(8):1327–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MR, Potenza MN. Recent Insights into the Neurobiology of Impulsivity. Current Addiction Reports. 2014;1(4):309–319. doi: 10.1007/s40429-014-0037-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L, Killeen PR, Fetterman JG. Changing rates of reinforcement perturbs the flow of time. Behavioral Processes. 1993;30(3):259–271. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(93)90138-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung IJ. Tutorial on maximum likelihood estimation. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 2003;47:90–100. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2496(02)00028-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. Response inhibition and disruptive behaviors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1008:170–182. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterlaan J, Logan GD, Sergeant JA. Response inhibition in AD/HD, CD, comorbid AD/HD + CD, anxious, and control children: a meta-analysis of studies with the stop task. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1998;39:411–425. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orduña V, Valencia-Torres L, Bouzas A. DRL performance of spontaneously hypertensive rats: Dissociation of timing and inhibition of responses. Behavioral Brain Research. 2009;201:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;43:434–442. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammsayer T, Altenmüller E. Temporal information processing in musicians and nonmusicians. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2006;24(1):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Raslear TG, Shurtleff D, Simmons L. Intertrial-interval effects on sensitivity (A′) and response bias (B”) in a temporal discrimination in rats. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1992;58(3):527–535. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1992.58-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins JN, Winocur G, Gray JA. The hippocampus, collateral behavior, and timing. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1983;97(6):857–72. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.97.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JB, Sabol KE, Seiden LS. DRL interresponse-time distributions: quantification by peak deviation analysis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1993;60 (2):361–385. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1993.60-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivalan M, Gregoire S, Dellu-Hagedorn F. Reduction of impulsivity with amphetamine in an appetitive fixed consecutive number schedule with cue for optimal performance in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:171–182. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. The 5-choice serial reaction time task: behavioural pharmacology and functional neurochemistry. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163(3–4):362–80. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosvold HE, Mirsky AF, Sarason I, Bransome ED, Beck LH. A continuous performance test of brain damage. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1956;20:343–350. doi: 10.1037/h0043220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell VA. Hypodopaminergic and hypernoradrenergic activity in prefrontal cortex slices of an animal model for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder – the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Behavioral Brain Research. 2002;130:191–196. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell VA. Dopamine hypofunction possibly results from a defect in glutamate-stimulated release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens shell of a rat model for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell VA. Overview of animal models of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Current Protocols in Neuroscience. 2011;54 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0935s54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell V, Allie S, Wiggins T. Increased noradrenergic activity in the prefrontal cortex slices of an animal model for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder – the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Behavioral Brain Research. 2000;117:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell VA, Sagvolden T, Johansen EB. Animal models of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behavioral and Brain Functions: BBF. 2005;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagvolden T, Berger DF. An Animal Model of Attention Deficit Disorder: The Female Shows More Behavioral Problems and Is More Impulsive than the Male. European Psychologist. 1996;1(2):113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sagvolden T, Metzger Ma, Schiørbeck HK, Rugland aL, Spinnangr I, Sagvolden G. The spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) as an animal model of childhood hyperactivity (ADHD): changed reactivity to reinforcers and to psychomotor stimulants. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1992;58(2):103–12. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(92)90315-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria F, Killeen PR. Evidence for impulsivity in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat drawn from complementary response-withholding tasks. Behavioral and Brain Functions: BBF. 2008;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria F, Thrailkill EA, Killeen PR. Timing with opportunity cost: Concurrent schedules of reinforcement improve peak timing. Learning and Behavior. 2009;37(3):217–229. doi: 10.3758/LB.37.3.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Tontsch C, Thoeny AL, Kaczkurkin A. Temporal reward discounting in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the contribution of symptom domains, reward magnitude, and session length. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):641–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B, Williams DR. Discrete-trials spaced responding in the pigeon: the dependence of efficient performance on the availability of a stimulus for collateral pecking. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1971;16(2):155–60. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1971.16-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiden LS, Andresen J, MacPhail RC. Methylphenidate and d-amphetamine: effects and interactions with alphamethyltyrosine and tetrabenazine on DRL performance in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1979;10:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(79)90236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma L, Markon KE, Clark LA. Toward a theory of distinct types of “impulsive” behaviors: A meta-analysis of self-report and behavioral measures. Psychology Bulletin. 2013;140(2):374–408. doi: 10.1037/a0034418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staddon JE, Higa JJ. Time and memory: towards a pacemaker-free theory of interval timing. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1999;71(2):215–51. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1999.71-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein N, Flanagan S. Human DRL performance, collateral behavior, and verbalization of the reinforcement contingency. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1974;3(1):27–28. doi: 10.3758/BF03333381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein N, Landis R. Mediating role of human collateral behavior during a spaced-responding schedule of reinforcement. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1973;97(1):28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tanno T, Kurashima R, Watanabe S. Motivational control of impulsive behavior interacts with choice opportunities. Learning and Motivation. 2011;42(2):145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2011.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Topping JS, Pickering JW, Jackson JA. Efficiency of DRL responding as a function of response effort. Psychonomic Science. 1971;24(3):149–150. doi: 10.3758/BF03331795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hest A, van Haaren F, van de Poll NE. Behavioral differences between male and female Wistar rats on DRL schedules: effect of stimuli promoting collateral activities. Physiology & Behavior. 1987;39(2):255–61. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson E, Zavala AR, Privitera GJ, Sanabria F. Response inhibition capacity and short-term memory are robust to the effects of high fat diet (HFD) during pre and periadolescence in press. [Google Scholar]

- Wearden J. The power law and Weber’s law in fixed-interval postreinforcement pausing: A scalar timing model. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section B. 1985;37(3):191–211. doi: 10.1080/14640748508402096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA, Eagle DM, Robbins TW. Behavioral models of impulsivity in relation to ADHD: translation between clinical and preclinical studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(4):379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodka EL, Mahone EM, Blankner JG, Larson JCG, Fotedar S, Denckla MB, Mostofsky SH. Evidence that response inhibition is a primary deficit in ADHD. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2007;29(4):345–56. doi: 10.1080/13803390600678046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]