Abstract

The voltage-gated calcium channel (Cav) β1a subunit (Cavβ1a) plays an important role in excitation-contraction coupling (ECC), a process in the myoplasm that leads to muscle-force generation. Recently, we discovered that the Cavβ1a subunit travels to the nucleus of skeletal muscle cells where it helps to regulate gene transcription. To determine how it travels to the nucleus, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screening of the mouse fast skeletal muscle cDNA library and identified an interaction with troponin T3 (TnT3), which we subsequently confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation and co-localization assays in mouse skeletal muscle in vivo and in cultured C2C12 muscle cells. Interacting domains were mapped to the leucine zipper domain in TnT3 COOH-terminus (160-244 aa) and Cavβ1a NH2-terminus (1-99 aa), respectively. The double fluorescence assay in C2C12 cells co-expressing TnT3/DsRed and Cavβ1a/YFP shows that TnT3 facilitates Cavβ1a nuclear recruitment, suggesting that the two proteins play a heretofore unknown role during early muscle differentiation in addition to their classical role in ECC regulation.

Keywords: Troponin T3, Cavβ1a, nuclear localization, skeletal muscle

INTRODUCTION

Excitation-contraction coupling (ECC) is the process that transduces muscle-fiber depolarization into a mechanical response. Two essential factors are dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) and ryanodine receptor-isoform-1 (RyR1; here, RyR). In response to membrane depolarization, DHPR conformation changes and interacts physically with the RyR, causing it to open and release Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, allowing muscle contraction [1, 2].

Cav1.1 is the primary DHPR subunit in skeletal muscle [3], and four distinct auxiliary subunits bind it to make up DHPR [4]. The most widely studied of these subunits is the cytosolic Cavβ1a subunit [5]. A muscle-specific member of the Cavβ family of proteins, it plays a classical role in chaperoning Cav1.1 to the plasma membrane and regulating L-type Ca2+ current [6–9]. The correct organization of Cav1.1 into tetrads within the t-tubule membrane is another specific function of the Cavβ1a isoform [10]. Note that ECC is totally absent in Cavβ1a null mutant mice, which causes muscle paralysis and embryonic lethality [6].

Troponin T (TnT) regulates ECC by forming a complex with TnI and TnC and interacting with tropomyosin (Tm) and the actin double-stranded filaments [11, 12]. Growing evidence from Drosophila melanogaster to mammals shows that, in addition to cytoplasmic localization, Tn and Tm are found in the nucleus [13–16]. Our group recently reported that fast skeletal muscle TnT3 is localized in the mouse skeletal muscle nucleus and, since a leucine zipper DNA-binding domain is present, may function as a transcription regulator [17, 18].

Our group also revealed that Cavβ1a exhibits a noncanonical nuclear localization sequence [19]. In addition, Cavβ1a enters the nucleus of muscle progenitor cells and regulate global gene expression. Specifically, it binds to a region of Myog promoter and inhibits myogenin gene expression. Identifying novel Cavβ1a interacting protein partners will clarify the initial steps by which it transfers to the muscle cell nucleus and regulates myogenesis. We screened a mouse muscle cDNA library using full-length Cavβ1a as the bait and, using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) analysis, discovered that it interacts with TnT3. Co-immunoprecipiation and co-localization assays in mouse muscle and C2C12 cells confirmed their interaction. We mapped the interacting domains of both proteins to the Cavβ1a NH2-terminus and TnT3 COOH-terminus to provide the first evidence that TnT3 and Cavβ1a interact through direct domain binding in both the cytoplasm and nucleus. Specifically, we find that TnT3 enhances Cavβ1a nuclear enrichment during early differentiation in C2C12 muscle cells. Our findings shed light on the mechanisms responsible for Cavβ1a shuttling to the nucleus and the timeframe for regulating the proliferation of muscle progenitor cells in myogenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents and antibodies

All reagents used for the Y2H assay were purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). Rabbit anti-TnT3 polyclonal antibody (ARP51287_T100) was purchased from Aviva Systems Biology (San Diego, CA), rabbit anti-Cavβ1a and mouse anti-Cav1.1 antibodies from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). Alexa 488- or 568-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). NA931V goat anti-mouse (Amersham Health, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) was used as a secondary antibody for immunoblots. leptomycin-B (LMB) was purchased from LC laboratories (Woburn, MA).

Plasmid construction

The cDNA encoding the mouse full-length Cavβ1a (1-524 aa) or its fragments, 1-57 aa, 58-99 aa, and 101-524 aa, was amplified by PCR from the full-length Cavβ1a encoding plasmid DNA Cavβ1a/YFP, kindly donated by Dr. Franz Hofmann (University of Saarland, Pharmacology and Toxicology), using primer sets containing EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites (Table 1). It was inserted downstream of the Gal4 DNA-binding domain in the (bait) vector pGBKT7 (Clontech).

Table 1. Forward and reverse PCR primers used for amplification of the different TnT3 and Cavβ1a domains for subcloning.

For each primer, the endonuclease restriction site used for cloning the insert into pGBKT7, pGADT7 and YFP is underlined.

| pGBKT7-Cavβ1a domain primers (EcoRI-BamHI) | |

| Cavβ1a Forward-1 | 5′-GCTAGAATTCATGGTCCAGAAGAGCGGCATGTCC-3′ |

| Cavβ1a Forward-58 | 5′-GCTAGAATTCATGGGCTCAGCAGAGTCCTACACG-3′ |

| Cavβ1a Forward-101 | 5′-GCTAGAATTCATGGTGGCTTTTGCTGTTCGGACAAAT-3′ |

| Cavβ1a Reverse-57 | 5′-GCTAGAATTCCTGGCGGACGAAGCTGTTGGA-3′ |

| Cavβ1a Reverse-99 | 5′-GCTAGAATTCTTTGGTCTTGGCTTTCTCGAG-3′ |

| Cavβ1a Reverse-524 | 5′-GCTAGAATTCCATGGCGTGCTCCTGAGGCTG-3′ |

| pGADT7-TnT3 domain primers (NdeI-XhoI) | |

| TnT3 Forward-1 | 5′-GCTACATATGATGTCTGACGAGGAAACTGAACAA-3′ |

| TnT3 Forward-160 | 5′-GCTACATATGAAAAAGAAGATTCTT-3′ |

| TnT3 Reverse-159 | 5′-GCTACATATG TTATTCCCGGGCTGTCTGTTT-3′ |

| TnT3 Reverse-244 | 5′-GCTACATATG TTACTTCCAGCGCCCACCGACTTT-3′ |

| Cavβ1a 100T/YFP primers (EcoRI-SalI) | |

| Cavβ1a100T/YFP-Forward | 5′-GCTAGAATTCCATGGTGGCTTTTGCTGTTCGGACAAAT-3′ |

| Cavβ1a100T/YFP-Reverse | 5′-GCTAGTCGACATGGCATGTTCCTGC-3′ |

The cDNA encoding the full-length mouse TnT3 (1-244 aa) or fragments (1-159 aa, 160-244 aa) was also amplified by PCR from the pGADT7-TnT3 (encoding 10-244 aa), extracted from yeast clone No.4 (Fig. 1D) from the cDNA library screening using primer sets containing NdeI and XhoI restriction sites (Table 1), and inserted downstream of the Gal4 DNA-activation domain in the (prey) vector pGADT7 (Clontech).

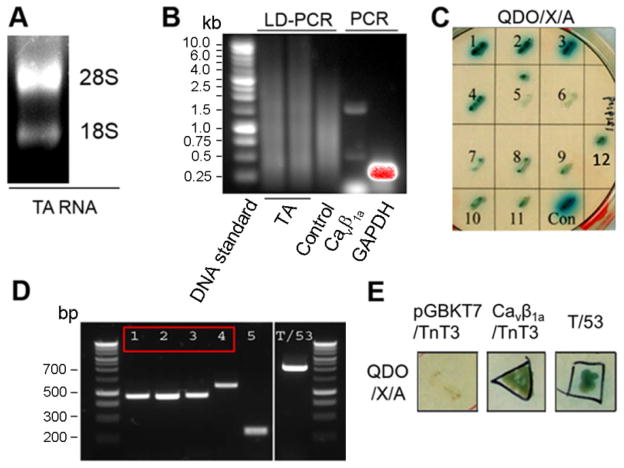

Figure 1. Interaction between Cavβ1a and TnT3 in the Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay.

(A) Total RNA from mouse TA muscle was separated on agarose gel. (B) Long-distance PCR (LD-PCR) of a cDNA pool to build the mouse TA muscle library. Control Human Placenta Poly A+ RNA was run in parallel. The quality of the cDNA pool was further tested by regular PCR using Cavβ1a or GAPDH primers. (C) Twelve positive yeast colonies grown on DDO/X (SD/–Leu/–Trp/X-α-Gal) agar plates turned blue, like the positive control (con, T/53). (D) Direct PCR gave a single band from most of the 12 yeast colonies (5 of which are shown together with the T/53 control colony). Colonies 1–4 (red box) correspond to a TnT3 region. (E) Yeast cells co-transformed with TnT3 fragment and Cavβ1a yield colonies similar to the control T/53 co-transformants on QDO/X/A agar plates (SD/–Ade/–His/–Leu/–Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA). In contrast, TnT3 co-transformed with empty bait vector (pGBKT7) showed poor survival.

To construct the DsRed fusion protein expression cDNAs, the TnT3 full-length cDNA was amplified by PCR using the TnT3 cDNA fragment subcloned in the pGADT7 vector as a template (obtained from a Y2H cDNA library screening, clone No.4). It was ligated into the pDsRed2-N1 vector (Clontech) between the HindIII and SacII restriction enzyme digestion sites. The other three TnT3 fragments encoding cDNAs were further cloned by PCR using the same strategy (for primer information, see [17]. The plasmid Cavβ1a/YFP electroporated into the mouse muscle was used as the template for PCR (primer sequences see Table 1) to generate the Cavβ1a 100aa truncated NH2-terminal expressing cDNA (Cavβ1a-100T/YFP), which was subcloned into the YFP vector between the EcoRI and SalI sites. The construction of recombinant adenoviral vector RAdCavβ1a/YFP has been described [19]. The Wake Forest School of Medicine (WFSM) DNA sequencing laboratory confirmed the sequences of all constructs.

Generation of the mouse TA muscle cDNA library in the pGADT7 vector

The cDNA library was constructed according to protocols in the Make Your Own “Mate & Plate™” Library System User Manual (PT4085-1, Clontech). Briefly, high-quality total RNA from mouse TA muscle was extracted using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized, and ds-cDNAs were amplified using long-distance PCR (LD-PCR) and further purified with CHROMA SPIN™ TE-400 columns. Library-scale transformation following the Yeastmaker Yeast Transformation System 2 User Manual then co-transformed 20 μl of ds-cDNA (5 μg) and 6 μl of pGADT7-Rec (3 μg) into competent Y187 yeast cells, which were resuspended in 15 ml of 0.9% (w/v) NaCl and spread on 150 mm SD/–Leu agar plates (150 μl per plate on ~100 plates). After incubation at 30°C for 3–4 days, all transformants were collected in 500 ml of freezing medium (YPDA medium and 25% glycerol) and prepared in 1 ml aliquots for short-term use and 50 ml aliquots for long-term storage at -80°C.

Screening of the mouse TA muscle cDNA library and the yeast two-hybrid assay

A 1-ml aliquot of this cDNA library was used for screening following the Matchmaker Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System User Manual (PT4084-1, Clontech). Y2H assay was performed as described above [20, 21]. Briefly, the pGBKT7 plasmids containing the full-length Cavβ1a cDNA were introduced into the Y2H gold yeast strain using a modified lithium-acetate protocol, and the transformants were selected on SD/-Trp plates. Mating between the selected Y2H gold and Y187 yeast cells was performed, and co-transformants were selected on agar plates SD/–Leu/–Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA (DDO/X/A). Colonies grew at 30°C for about 5 days. Those that turned blue were then grown on agar plates SD/–Ade/–His/–Leu/–Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA (QDO/X/A), and blue colonies were finally selected as the positive clones for further cDNA insert analysis using Matchmaker™ Insert Check PCR Mix (PT4102-2, Clontech). PCR products were analyzed with agrose gel electrophoresis and sequenced using pGADT7 sequencing primers: pGADT7F, 5′-CTATTCGATGATGAAGATACCCCACCAAACCCA-3′; pGADT7R, 5′-GTGAACTTGCGGGGTTTTTCAGTATCTACGATT-3′(Clontech). Each sequence was finally blasted on Genebank.

To further test TnT3-Cavβ1a interaction domains, different pairs of prey and bait plasmids were co-transformed into Y2H gold and plated on DDO/X to detect positive interactions.

Cell culture, transfection, and transduction

The mouse skeletal muscle cell line C2C12 was cultured as described [22]. Briefly, undifferentiated myoblasts were plated on tissue culture dishes or glass coverslips coated with 0.5% gelatin in growth medium consisting of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, 1 g/l glucose) containing 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA) and 2 mM Glutamax (Invitrogen). When cells reached 70% confluence, the medium was replaced by differentiation medium consisting of DMEM containing 2% horse serum and 2 mM Glutamax. For cell transfection, we used Lipofactamine 2000 (Invitrogen). RAd Cavβ1a/YFP was used for transduction of C2C12 cells and expression of Cavβ1a/YFP [19].

Animals and tissue lysates

Tibialis anterior (TA) muscles were dissected from C57B16 or our colony of FVB (Friend Virus B) mice, which we have used before as a model of aging skeletal muscle [23, 24]. Mice were housed at WFSM, and their handling and other procedures were approved by its Animal Care and Use Committee. They were killed by cervical dislocation.

To prepare whole TA muscle lysate, we used a lysis buffer modified from that reported by Beguin et al. [25]. Briefly, 50 mg of TA muscle were frozen, pulverized in liquid nitrogen, and homogenized in 2 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 0.2% Tween-20 supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail). Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation, and the soluble supernatants were saved as whole cell lysis.

Cytosolic and membrane fractioning were performed as described [26–28]. Briefly, TA muscles were homogenized using a handheld Tissue Tearor™ in ice-cold buffer A (20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 mM sodium phosphate monobasic, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 303 mM sucrose with a complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN]). The homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C in a Beckman Type Ti.70i rotor. The supernatant was saved as the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was rinsed with ice cold PBS and resuspended with a glass homogenizer in fresh digitonin buffer (1% digitonin [w/v], 185 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4 with a complete protease inhibitor cocktail) as the membrane fraction. Protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad DC assay (Hercules, CA).

Co-immunoprecipitation of TnT3 and Cavβ1a in C2C12 cells or mouse skeletal muscle in vivo

Both mouse muscle and C2C12 whole cell lysates were used for immunoprecipiation following a described protocol [22]. Briefly, C2C12 cells were infected with an adenovirus expressing RAdCavβ1a/YFP for 2 d, cultured in differentiation medium for 2–3 d, and the whole cell lysates extracted after sitting on ice for 1 h in 1 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1mM DTT, and 0.2% Tween20) supplemented with a complete mini-protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). They were then harvested with a rubber policeman. Tubes containing the cell extracts were spun for 15 min at 16,000 g in a microcentrifuge at 4°C. Combined with 20 μl of a 50% slurry of protein A/G agarose beads (Invitrogen), the supernatants were kept rotating at 4°C for 2 h to clear any protein that bound nonspecifically to the beads. Another batch of 40 μl beads was incubated at 4°C for 8 h with 10 μl mouse anti- Cavβ1a or control mouse IgG (Santa Cruz). Cavβ1a antibody or IgG-coated beads were combined with the cleared supernatant and left to rotate for 8 h at 4°C. Beads were washed five times, and bound material was eluted in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were boiled and separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed with anti-TnT3 and anti-Cavβ1a antibodies.

Electrophoresis and immunoblotting

SDS-PAGE was conducted using a 4.5% stacking gel with a 10% resolving gel in a Mini-PROTEAN gel system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hemel-Hemptstead, Herts., UK) as described [27]. Gels were transferred to PVDF membranes (Amersham Health, Little Chalfont, Bucks., UK) at 4°C overnight. Blots were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk with 0.1% Tween in TBS for primary antibody incubation. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used at a 1:25000 dilution at room temperature for 1 h. Band intensity was measured using a Kodak Gel Doc imaging system (Carestream Health Inc., Rochester, NY), and peroxidase activity with the Amersham ECL plus western blot detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Muscle electroporation and single intact fiber preparation

Two mice strains, C57B16 and FVB, were used for intramuscular plasmid injection and electroporation according to [29]. Briefly, flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles were injected with 5 μl of 2 mg/ml hyaluronidase and, 1 h later, with 20 μg DsRed conjugated TnT3 cDNAs or control DsRed cDNA with 20 μg Cavβ1a/YFP or GFP cDNA. Ten minutes later, a pair of sterile, gold-plated acupuncture needles was placed under the skin on adjacent sides of the muscle. Twenty, 100 V/cm, 20-ms square-wave pulses of 1-Hz frequency were generated using a Grass stimulator (Grass S48; W. Warwick, RI) and delivered to the muscle.

The technique for single intact fiber dissection followed described procedures [17, 30–32]. After isolation, the fibers in suspension were pelleted for 20 min and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, stained with Hoechst 33342, and mounted for microscopic analysis.

Microscopy and image analysis

At room temperature, cells cultured on coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, and their membranes permeabilized for 5 min with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS buffer after fixation. After three washes with PBS, they were incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer (PBS with 10% normal goat serum [Sigma]), and labeled with primary and secondary antibodies for 2 and 1 h, respectively. They were then counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) and mounted in DAKO fluorescent mounting medium (Carpinteria, CA). Widefield immunofluorescence images were taken on an inverted motorized fluorescent microscope (Olympus, IX81, Tokyo, Japan) and an Orca-R2 Hamamatsu CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Japan). Camera driver and image acquisition were controlled with a MetaMorph Imaging System (Olympus). Digital image files were transferred to Photoshop 7.0 to assemble montages.

RESULTS

Cavβ1a interacts with TnT3 via Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

To identify proteins interacting with Cavβ1a, we first constructed a C57BL6 mouse cDNA library using the total RNA extracted from the TA muscle (Fig. 1A). All cDNAs were amplified by long-distance PCR (LD-PCR) and the yield was comparable to that of the control poly A+ human placenta RNA derived cDNAs by agrose gel analysis, which showed similar DNA smear pattern spanning wide range of length (Fig. 1B). The the constructed cDNA library was further tested by regular PCR of randomly selected specific genes; e.g., Cavβ1a and GAPDH (Fig. 1B). Using full-length Cavβ1a as bait, more than 6 × 107 colonies were screened by Y2H assay, which identified 12 positive colonies by monitoring the activation of reporter genes (Fig. 1C). The prey cDNA insert in each positive colony was amplified by PCR and the products were separated on agrose gel. Representative PCR bands from 5 different colonies were shown (Fig. 1D). PCR products were further sequenced and blasted. From the 12 positive colonies, sequences of 4 cDNAs were matched to different coding region of TnT3 and the longest cDNA from the 4 was matched to the region that encodes amino acids (aa) 10 to 244 of protein TnT3, isoform 8 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_001157142.1). The interaction between this TnT3 fragment and Cavβ1a was confirmed by a more stringent selection condition, comparable to that of the positive control (Fig. 1E).

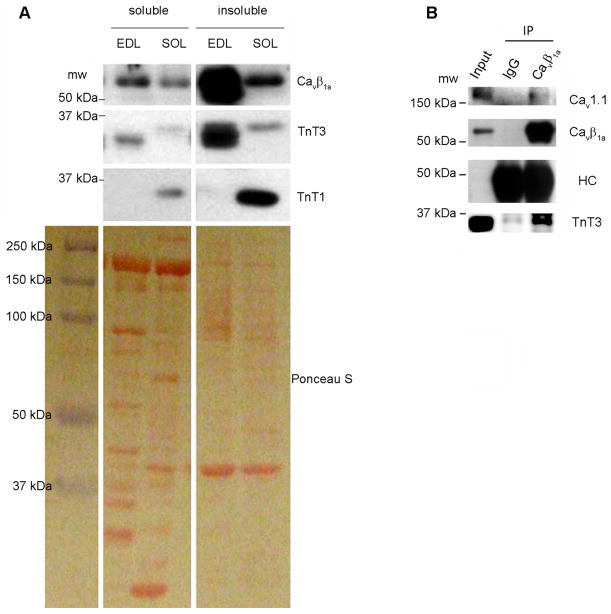

Cavβ1a interacts with TnT3 in muscle in vivo

We next sought to test if the interaction between Cavβ1a and TnT3 occurs in vivo, in mouse skeletal muscle. We first verified by immunoblot that both Cavβ1a and TnT3 are abundant in fast skeletal muscle. Soluble and insoluble fractionation of the mouse fast extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and slow soleus (SOL) muscles were immunoblotted with antibodies that recognize TnT3, TnT1 (a slow skeletal muscle-specific isoform), and Cavβ1a (Fig. 2A). As expected, TnT3 was highly expressed in EDL, particularly the insoluble pool containing mainly myofibrillar proteins, while TnT1 was more abundant in SOL. A weak band detected with TnT3 antibody showed up in both EDL and SOL, indicating different TnT3 isoforms may exist in those muscles, as has been reported previously[33]. Cavβ1a was also highly expressed in the insoluble pool, much more in EDL than SOL. We found that, in contrast to IgG, the Cavβ1a antibody induced endogenous TnT3 and Cavβ1a co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2B). Cav1.1 was also detected in the immunoprecipitates (Fig. 2B), indicating that TnT3, Cavβ1a, and Cav1.1 form a complex in vivo. Unfortunately, reverse co-immunoprecipitation was not feasible because commercially and noncommercially available TnT3 antibodies failed to pull down TnT3.

Figure 2. TnT3 interacts with Cavβ1a in skeletal muscles in vivo.

(A) Cytosol and membrane fractions of mouse EDL and SOL muscles were immunoblotted with TnT3, TnT1, and Cavβ1a antibodies. Ponceau S staining of a PVDF membrane shows an even protein loading. (B) Endogenous TnT3 co-immunoprecipitated by the Cavβ1a antibody but not control IgG. Cav1.1 was also detected in the immunoprecipitates. The antibody against heavy chain (HC) shows a similar loading of Cavβ1a antibody and IgG. Whole EDL muscle lysates were used as the input.

Cavβ1a interacts with TnT3 in cultured C2C12 and in mouse muscle in vivo

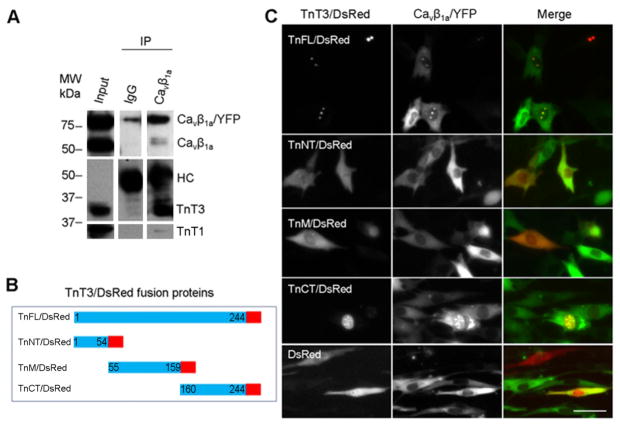

To examine the effect of cell-differentiation on the interaction between Cavβ1a and TnT3, we expressed RAd Cavβ1a/YFP in C2C12 cells and tested its interaction with endogenous TnT3. Since TnT3 does not express in undifferentiated C2C12 myoblasts while both TnT3 and Cavβ1a are highly expressed in differentiated C2C12 [19], we tested their interaction in cells cultured in differentiation medium. Given that the Cavβ1a antibody worked efficiently for co-immunoprecipitation analysis, we further used it to pull down Cavβ1a/YFP. Both endogenous Cavβ1a and overexpressed Cavβ1a/YFP were pulled down using the Cavβ1a antibody, while TnT3 was co-immunoprecipitated (Fig. 3A). The data also indicate that the YFP tag of the Cavβ1a COOH-terminal does not interfere with its TnT3 interaction.

Figure 3. Interaction between Cavβ1a and TnT3 in C2C12 cells.

(A) C2C12 cells transduced with RAdCavβ1a/YFP were cultured until myotubes formed. Whole cell lysis preparations were immunoprecipitated with Cavβ1a antibody or IgG and immunoblotted. The antibody against heavy chain (HC) indicates a similar Cavβ1a antibody and IgG loading. (B) Diagram of the DsRed-conjugated TnT3 constructs. (C) Co-expression of Cavβ1a/YFP and various TnT3/DsRed constructs in C2C12 cells cultured in growth medium. Both TnFL/DsRed and TnCT/DsRed localized in the nucleus and co-localized with Cavβ1a/YFP. In contrast, Cavβ1a/YFP expression, alone or co-expressed with TnNT/DsRed, TnM/DsRed, or control DsRed, was localized throughout the cell. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Since Cav1.1 forms a complex with Cavβ1a and TnT3, we next asked whether the interaction between Cavβ1a and TnT3 depends on Cav1.1. We used undifferentiated C2C12 myoblasts, which do not express Cav1.1 [19, 34]and performed a co-localization assay by expressing full-length DsRed tagged-TnT3 (TnFL/DsRed) or fragments and Cavβ1a/YFP (Fig. 3B, C). Consistent with our previous reports, only TnFL/DsRed and TnCT/DsRed localized in the C2C12 nucleus [17, 18]. Strikingly, Cavβ1a/YFP was also enriched in the nucleus and co-localized with TnFL/DsRed or TnCT/DsRed. In contrast, TnNT/DsRed or TnM/DsRed showed cell distribution similar to that of control DsRed, which does not show any clear co-localization with Cavβ1a/YFP in the nucleus. These data indicate that TnT3 interacts with Cavβ1a in the absence of Cav1.1. Additionally, nonmyofilament-associated TnT3 may facilitate Cavβ1a nuclear enrichment since Cavβ1a/YFP expression alone does not show strong nuclear localization in C2C12 [19].

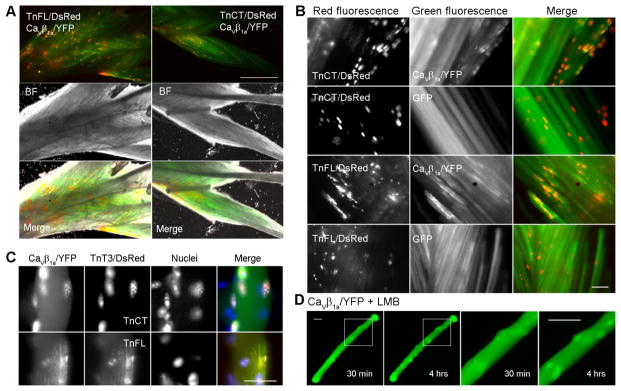

Nonmyofilament-associated TnT3 overexpression is toxic in C2C12 cells [17, 18], so we could not analyze the interaction between TnT3/DsRed and Cavβ1a/YFP or endogenous Cavβ1a at specific stages of differentiation. Therefore, we co-expressed TnCT/DsRed or TnFL/DsRed and Cavβ1a/YFP in the mouse FDB muscle by in vivo electroporation (Fig. 4A). Both TnCT/DsRed and TnFL/DsRed showed a punctate distribution pattern within the nucleus, while only TnFL/DsRed showed additional striated distribution within the myoplasm (Fig. 4B) as we previously reported [17]. This pattern was verified by examining their co-localization at the single-fiber level (Fig. 4C). TnCT/DsRed expression is restricted to the myonucleus and, accordingly, we saw enriched Cavβ1a/YFP only in the nucleus of these cells [17, 18]. In contrast, TnFL/DsRed is distributed in the nucleus and along the myoplasm in the typical striated pattern (Fig. 4C bottom panel), and Cavβ1a/YFP is enriched in both locations. In contrast, Cavβ1a/YFP alone in the FDB did not any apparent nuclear presence, yet after treatment with LMB (20 nM, 3 hrs) on single isolated FDB fibers, the nuclear enrichment of Cavβ1a/YFP is greatly enhanced (Fig. 4D). These data indicate that TnT3 interacts with Cavβ1a in both cytoplasm/plasma membrane and myonucleus, and the COOH-terminus of TnT3 may contain the domain that interacts with Cavβ1a. In addition, TnT3 may facilitate Cavβ1a nuclear localization in muscle in vivo through their interaction.

Figure 4. Co-localization of Cavβ1a/YFP and TnFL/DsRed or TnCT/DsRed in mouse skeletal muscle in vivo.

(A) Mouse FDB electroporated with Cavβ1a/YFP and TnFL/DsRed or TnCT/DsRed. Whole FDB muscles were dissected and imaged 2 weeks after electroporation. (B) Enlarged view of image A. Cavβ1a/YFP but not GFP shows a punctate distribution, which co-localized with TnCT/DsRed or TnFL/DsRed. (C) Single FDB fiber reveals that TnCT/DsRed is only found in the nucleus and co-localizes with Cavβ1a/YFP; TnFL/DsRed is localized in both cytoplasm (striation pattern) and nucleus; and Cavβ1a/YFP co-localized in both locations. (D) LMB (20 nM, 3 hrs) treated single fiber with Cavβ1a/YFP overexpression show time-dependent nuclear enrichment of Cavβ1a/YFP. The last two columns show enlarged view of the boxed areas in the first two columns, respectively. Scale bar = 800 μm (A) and 25 μm (B, C, D).

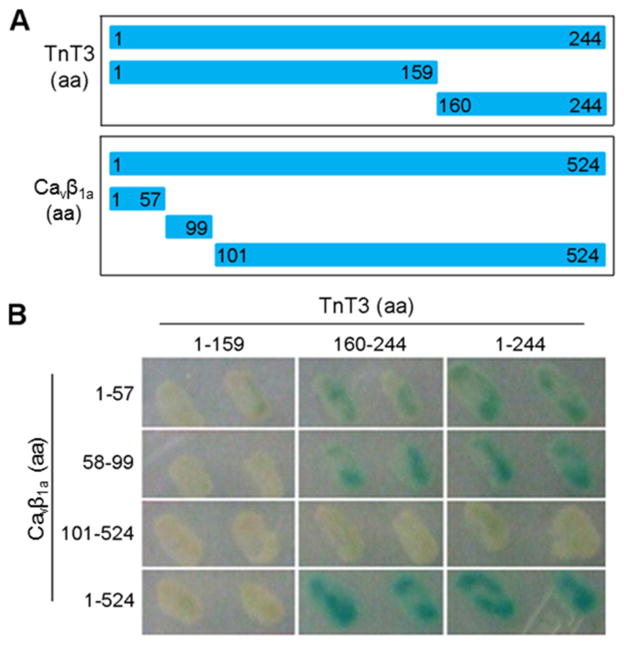

Mapping the TnT3/Cavβ1a interaction domain

We used the Y2H assay to determine the Cavβ1a/TnT3 interaction domain. We found that only in yeast cells transformed with TnT3 COOH-terminal cDNA constructs (160-244 aa) and Cavβ1a NH2-terminal cDNA constructs (1-57 aa or 58-99 aa) was reporter gene β-galactosidase (blue yeast colony) obviously activated, as in yeast cells co-transformed with full-length Cavβ1a and TnT3 (Fig. 5A, B). Therefore, the conserved SH3 and GKdomains [35] are not needed for Cavβ1a/TnT3 interaction.

Figure 5. Mapping of the TnT3 and Cavβ1a interaction domain by Y2H assay.

(A) Diagram showing various TnT3 and Cavβ1a constructs used for the two-hybrid assay. (B) X-Gal assay revealed the extent of protein interaction.

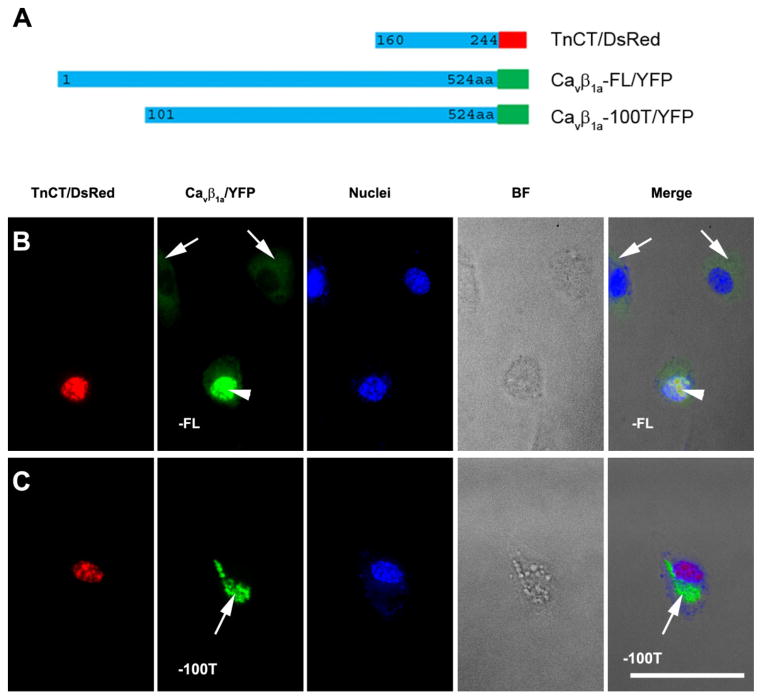

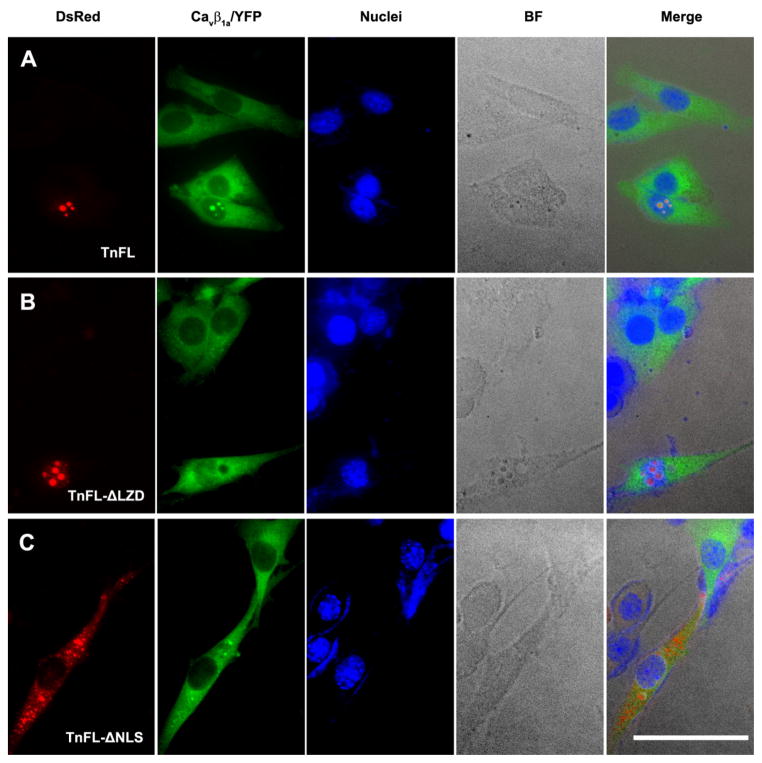

The interaction between the TnT3 COOH-terminus and the Cavβ1a NH2-terminus was further verified by co-expressing them in C2C12 cells. TnCT/DsRed localized exclusively in the nucleus [17, 18] and recruited full-length Cavβ1a/YFP in this compartment (Fig. 3C and Fig. 6B). In contrast, the Cavβ1a/YFP 100 aa truncated NH2-terminal (Cavβ1a100T/YFP) was not recruited to the nucleus and did not co-localize with TnCT/DsRed (Fig. 6C). This finding indicates that the Cavβ1a NH2-terminus 100 aa is needed for interaction with the TnT3 COOH-terminus and may contain a nuclear localization signal since ~40% of the Cavβ1a -100T/YFP showed a punctate distribution pattern in the cytoplasm only (Fig. 6C), while the Cavβ1a/YFP usually showed mainly a cytoplasmic distribution (Fig. 6B, arrows). To further map the Cavβ1a interacting domain the TnT3 COOH terminus, we took advantage of our previously constructed TnFL/DsRed cDNAs that expressing TnFL proteins with either nuclear localization domain truncated (TnFL-ΔNLS/DsRed) or leucine zipper domain truncated (TnFL-ΔLZD/DsRed) [18]. When coexpressed with Cavβ1a/YFP in C2C12 myoblasts, TnFL/DsRed greatly enriched Cavβ1a/YFP in the nucleus (Fig. 7A); TnFL-ΔLZD/DsRed, which still localized in the nucleus, showed diminished nuclear enrichment of Cavβ1a/YFP (Fig. 7B); TnFL-ΔNLS/DsRed with reduced nuclear localization also failed to enrich Cavβ1a/YFP in the nucleus (Fig. 7C). These data indicated the LZD domain is needed for TnT3 interaction with Cavβ1a. We conclude that the Cavβ1a NH2-terminus (100 aa) plays a major role in both its nuclear localization and interaction with TnT3 LZD domain.

Figure 6. The Cavβ1a NH2-terminal 100aa is needed for its interaction with TnT3 in C2C12.

(A) Diagram of DsRed-tagged TnCT and YFP-tagged, full-length Cavβ1a (Cavβ1a-FL/YFP) or the Cavβ1a/YFP 100 aa truncated NH2-terminal (Cavβ1a-100T/YFP). (B) When transiently overexpressed in C2C12 myoblasts, Cavβ1aFL/YFP alone mainly localized in the cytoplasm (arrows). In contrast, when co-expressed with TnCT/DsRed, Cavβ1a-FL/YFP was enriched in the nucleus and co-localized with TnCT/DsRed (arrow heads). (C) Cavβ1a-100T/YFP mainly localized in points in the cytoplasm (~40%) even when co-expressed with TnCT/DsRed (arrows). BF, bright field. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 7. The LZD domain, but not NLS domain in TnT3 is needed for its interaction with Cavβ1a in C2C12.

(A) TnFL/DsRed (Full length TnT3) coexpression with full-length Cavβ1a (Cavβ1a-FL/YFP) enriched nuclear Cavβ1a-FL/YFP. (B) TnFL-ΔLZD/DsRed (Full length TnT3 with LZD domain partially removed) coexpression with full-length Cavβ1a (Cavβ1a-FL/YFP) showed diminished enrichment of Cavβ1a-FL/YFP in the nucleus. (C) TnFL-ΔNLS/DsRed (Full length TnT3 with NLS domain removed) coexpression with full-length Cavβ1a (Cavβ1a-FL/YFP) showed diminished nuclear enrichment of both proteins. BF, bright field. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Endogenous TnT3 enriches Cavβ1a in the C2C12 cell nucleus early in differentiation

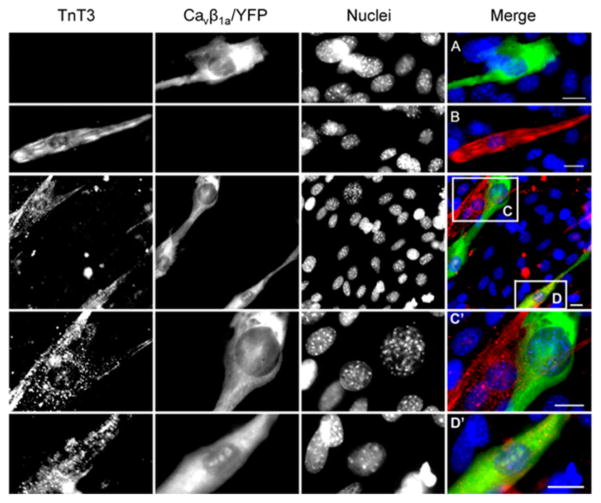

We recently found Cavβ1a enters the nucleus of myoblasts, before differentiation, where it functions as a transcription regulator [19]. Therefore, we wanted to determine at what stage of myogenic differentiation TnT3 interacts with Cavβ1a. Immunofluorescence staining of endogenous TnT3 showed that Cavβ1a/YFP is mainly localized in the cytoplasm of undifferentiated, TnT3-negative C2C12 myoblasts (Fig. 8A, C, C′). In contrast, we detected TnT3 in the cytoplasm and nucleus of elongated, mononuleated C2C12 cells (Fig. 8B), a typical C2C12 cell phenotype in the early stages of differentiation [22]. Cavβ1a/YFP was enriched accordingly and co-localized with endogenous TnT3 in the nucleus (Fig. 8D, D′). Our findings imply that TnT3 regulates Cavβ1a subcellular distribution during an early stage of muscle cell differentiation, before fusion takes place.

Figure 8. Endogenous TnT3 enriches nuclear Cavβ1a during the early differentiation of C2C12 cells.

Cavβ1a/YFP overexpression in undifferentiated C2C12 myoblasts was observed primarily in the cytoplasm and weakly in the nucleus (A, C, and C′). Endogenous TnT3 was detected by immunfluorescence in mononucleated, elongated cells in both cytoplasm and nucleus (B, D, and D′). In the elongated C2C12 cells at an early stage of differentiation and co-expressed with Cavβ1a/YFP, both TnT3 and Cavβ1a/YFP were observed in the nucleus; the latter was greatly enriched (D, D′) compared to the case when it only was expressed in undifferentiated myoblasts (A, C, and C′).

DISCUSSION

Both TnT3 and Cavβ1a play major roles in skeletal muscle ECC [10, 35–37]. Here, we provide the first evidence that TnT3 interacts with Cavβ1a; specifically through the COOH-terminus (160-244 aa) of TnT3 and NH2-terminus (1-99 aa) of Cavβ1a. This interaction seems to occur in both the myoplasm and nucleus and to regulate Cavβ1a nuclear enrichment during the early differentiation of muscle cells, suggesting a possible involvement in transcription regulation [16–19, 38].

Cavβ1a has long been known for its essential role in regulating skeletal muscle ECC, which takes place in the myoplasm. Full-length Cavβ1a/YFP is distributed throughout the cells, with a small amount in the nucleus, but its nuclear accumulation was enhanced by blocking the CRM1 nuclear export channel with leptomycin-B [19]. The 100 aa truncation of its NH2-terminus induced a redistribution of Cavβ1a/YFP, with ~40% showing a punctate distribution pattern in the cytoplasm, indicating that the NH2-terminus plays a critical role in mediating Cavβ1a/YFP nuclear localization. This finding could be of great significance since the domain that binds to the TnT3 COOH-terminus is also localized in this region. We speculate that the NH2-terminus mediates Cavβ1a nuclear localization and interaction with TnT3 LZD domain and is unique to the Cavβ1a subunit isoform, which has a highly variable NH2-terminal region [38]. All Cavβ subunit isoforms contain variable NH2- and COOH-terminal domains as well as conserved SH3, H, and GK domains [35]. In contrast, the conserved SH3, HOOK, and GK domains that localize beyond the NH2-terminus do not seem to play a key role in mediating Cavβ1a nuclear localization and interaction with TnT3. Since all four Cavβ subunit isoforms have been reported to enter the nucleus [5] and some data suggest a possible role for the SH3 domain in this function [39, 40], the Cavβ1a nuclear localization mediated by the NH2-terminus seems unique to fast skeletal muscle. To support this notion, we showed that both Cavβ1a and TnT3 are more abundantly co-expressed in fast than slow muscle.

The TnT3 nuclear localization signal, recently mapped by our group [18], facilitates Cavβ1a nuclear enrichment. As the SH3 domain is needed for Cavβ1a nuclear localization in undifferentiated myoblasts [19], the newly identified Cavβ1a-TnT3 interaction supports a novel role for TnT3 in the early differentiation of muscle progenitor cells. TnT3 binding to Cavβ1a may affect its subcellular distribution and interaction with other Cavβ1a partners, including Cav1.1. Conversely, Cavβ1a may regulate TnT3’s nuclear function. We reported that increased Cavβ1a expression decreases Cav1.1 expression with aging [27], which may be explained by Cavβ1a’s interference with TnT3 binding to Cacna1s, the gene encoding Cav1.1 (unpublished data).

The newly described interaction between Cavβ1a and TnT3 explains how Cavβ1a enters the nucleus to act as a gene-transcription regulator. Our data also suggest that TnT3 plays a role in nuclear signaling, the specific pathways of which remain to be elucidated.

Highlights.

Previously, we demonstrated that Cavβ1a is a gene transcription regulator

Here, we show that TnT3 interacts with Cavβ1a

We mapped TnT3 and Cavβ1a interaction domain

TnT3 facilitates Cavβ1a nuclear enrichment

The two proteins play a heretofore unknown role during early muscle differentiation

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants, R01AG13934 and R01AG15820 to O.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Melzer W, Herrmann-Frank A, Luttgau HC. The role of Ca2+ ions in excitation-contraction coupling of skeletal muscle fibres. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241:59–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(94)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delbono O, Messi ML, Wang ZM, Treves S, Mosca B, Bergamelli L, Nishi M, Takeshima H, Shi H, Xue B, Zorzato F. Endogenously determined restriction of food intake overcomes excitation-contraction uncoupling in JP45KO mice with aging. Experimental gerontology. 2012;47:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catterall WA, Perez-Reyes E, Snutch TP, Striessnig J. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:411–425. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flucher BE, Obermair GJ, Tuluc P, Schredelseker J, Kern G, Grabner M. The role of auxiliary dihydropyridine receptor subunits in muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2005;26:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10974-005-9000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buraei Z, Yang J. The ss subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregg RG, Messing A, Strube C, Beurg M, Moss R, Behan M, Sukhareva M, Haynes S, Powell JA, Coronado R, Powers PA. Absence of the beta subunit (cchb1) of the skeletal muscle dihydropyridine receptor alters expression of the alpha 1 subunit and eliminates excitation-contraction coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13961–13966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strube C, Beurg M, Powers PA, Gregg RG, Coronado R. Reduced Ca2+ current, charge movement, and absence of Ca2+ transients in skeletal muscle deficient in dihydropyridine receptor beta 1 subunit. Biophys J. 1996;71:2531–2543. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79446-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beurg M, Sukhareva M, Strube C, Powers PA, Gregg RG, Coronado R. Recovery of Ca2+ current, charge movements, and Ca2+ transients in myotubes deficient in dihydropyridine receptor beta 1 subunit transfected with beta 1 cDNA. Biophys J. 1997;73:807–818. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78113-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuhuber B, Gerster U, Doring F, Glossmann H, Tanabe T, Flucher BE. Association of calcium channel alpha1S and beta1a subunits is required for the targeting of beta1a but not of alpha1S into skeletal muscle triads. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5015–5020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schredelseker J, Di Biase V, Obermair GJ, Felder ET, Flucher BE, Franzini-Armstrong C, Grabner M. The beta 1a subunit is essential for the assembly of dihydropyridine-receptor arrays in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17219–17224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508710102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebashi S. Regulatory mechanism of muscle contraction with special reference to the Ca-troponin-tropomyosin system. Essays Biochem. 1974;10:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.el-Saleh SC, Warber KD, Potter JD. The role of tropomyosin-troponin in the regulation of skeletal muscle contraction. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1986;7:387–404. doi: 10.1007/BF01753582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisen J. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science. 2009;324:98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asumda FZ, Chase PB. Nuclear cardiac troponin and tropomyosin are expressed early in cardiac differentiation of rat mesenchymal stem cells. Differentiation. 2012;83:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahota VK, Grau BF, Mansilla A, Ferrus A. Troponin I and Tropomyosin regulate chromosomal stability and cell polarity. Journal of Cell Science. 2009;122:2623–2631. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chase PB, Szczypinski MP, Soto EP. Nuclear tropomyosin and troponin in striated muscle: new roles in a new locale? J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10974-013-9356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang T, Birbrair A, Wang ZM, Taylor J, Messi ML, Delbono O. Troponin T nuclear localization and its role in aging skeletal muscle. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:353–370. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9368-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang T, Birbrair A, Delbono O. Nonmyofilament-associated troponin T3 nuclear and nucleolar localization sequence and leucine zipper domain mediate muscle cell apoptosis. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2013;70:134–147. doi: 10.1002/cm.21095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor J, Pereyra A, Zhang T, Messi ML, Wang ZM, Herenu C, Kuan PF, Delbono O. The Cavbeta1a subunit regulates gene expression and suppresses myogenin in muscle progenitor cells. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:829–846. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201403021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang T, Xu Q, Chen FR, Han QD, Zhang YY. Yeast two-hybrid screening for proteins that interact with alpha1-adrenergic receptors. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2004;25:1471–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Q, Xu N, Zhang T, Zhang H, Li Z, Yin F, Lu Z, Han Q, Zhang Y. Mammalian tolloid alters subcellular localization, internalization, and signaling of alpha(1a)-adrenergic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:532–541. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.016451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang T, Zaal KJ, Sheridan J, Mehta A, Gundersen GG, Ralston E. Microtubule plus-end binding protein EB1 is necessary for muscle cell differentiation, elongation and fusion. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1401–1409. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renganathan M, Messi ML, Delbono O. Overexpression of IGF-1 exclusively in skeletal muscle prevents age-related decline in the number of dihydropyridine receptors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28845–28851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payne AM, Zheng Z, Gonzalez E, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Delbono O. External Ca(2+)-dependent excitation--contraction coupling in a population of ageing mouse skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2004;560:137–155. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.067322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beguin P, Mahalakshmi RN, Nagashima K, Cher DH, Ikeda H, Yamada Y, Seino Y, Hunziker W. Nuclear sequestration of beta-subunits by Rad and Rem is controlled by 14–3–3 and calmodulin and reveals a novel mechanism for Ca2+ channel regulation. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung AT, Imagawa T, Campbell KP. Structural characterization of the 1,4-dihydropyridine receptor of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel from rabbit skeletal muscle. Evidence for two distinct high molecular weight subunits. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7943–7946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor JR, Zheng Z, Wang ZM, Payne AM, Messi ML, Delbono O. Increased CaVbeta1A expression with aging contributes to skeletal muscle weakness. Aging Cell. 2009;8:584–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Washabaugh CH, Ontell MP, Shand SH, Bradbury N, Kant JA, Ontell M. Neuronal control of myogenic regulatory factor accumulation in fetal muscle. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:732–745. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiFranco M, Neco P, Capote J, Meera P, Vergara JL. Quantitative evaluation of mammalian skeletal muscle as a heterologous protein expression system. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;47:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez E, Messi ML, Delbono O. The specific force of single intact extensor digitorum longus and soleus mouse muscle fibers declines with aging. J Membr Biol. 2000;178:175–183. doi: 10.1007/s002320010025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lannergren J, Westerblad H. The temperature dependence of isometric contractions of single, intact fibres dissected from a mouse foot muscle. J Physiol. 1987;390:285–293. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birbrair A, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Delbono O. Nestin-GFP transgene reveals neural precursor cells in adult skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brotto MA, Biesiadecki BJ, Brotto LS, Nosek TM, Jin JP. Coupled expression of troponin T and troponin I isoforms in single skeletal muscle fibers correlates with contractility. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C567–576. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00422.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varadi G, Orlowski J, Schwartz A. Developmental regulation of expression of the alpha 1 and alpha 2 subunits mRNAs of the voltage-dependent calcium channel in a differentiating myogenic cell line. FEBS letters. 1989;250:515–518. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGee AW, Nunziato DA, Maltez JM, Prehoda KE, Pitt GS, Bredt DS. Calcium channel function regulated by the SH3-GK module in beta subunits. Neuron. 2004;42:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomes AV, Guzman G, Zhao J, Potter JD. Cardiac troponin T isoforms affect the Ca2+ sensitivity and inhibition of force development. Insights into the role of troponin T isoforms in the heart. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35341–35349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204118200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacFarland SM, Jin JP, Brozovich FV. Troponin T isoforms modulate calcium dependence of the kinetics of the cross-bridge cycle: studies using a transgenic mouse line. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;405:241–246. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karunasekara Y, Dulhunty AF, Casarotto MG. The voltage-gated calcium-channel beta subunit: more than just an accessory. Eur Biophys J. 2009;39:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi SX, Miriyala J, Tay LH, Yue DT, Colecraft HM. A CaVbeta SH3/guanylate kinase domain interaction regulates multiple properties of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:365–377. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hibino H, Pironkova R, Onwumere O, Rousset M, Charnet P, Hudspeth AJ, Lesage F. Direct interaction with a nuclear protein and regulation of gene silencing by a variant of the Ca2+-channel beta 4 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:307–312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136791100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]