Abstract

Human ‘laminopathy’ diseases result from mutations in genes encoding nuclear lamins or nuclear envelope (NE) transmembrane proteins (NETs). These diseases present a seeming paradox: the mutated proteins are widely expressed yet pathology is limited to specific tissues. New findings suggest tissue-specific pathologies arise because these widely expressed proteins act in various complexes that include tissue-specific components. Diverse mechanisms to achieve NE tissue-specificity include tissue-specific regulation of the expression, mRNA splicing, signaling, NE-localization and interactions of potentially hundreds of tissue-specific NETs. New findings suggest these NETs underlie tissue-specific NE roles in cytoskeletal mechanics, cell-cycle regulation, signaling, gene expression and genome organization. This view of the NE as ‘specialized’ in each cell type is important to understand the tissue-specific pathology of NE-linked diseases.

Introduction

As the complexity of multicellular organisms increased during evolution, so did the number of proteins that localize and function at the nuclear envelope (NE) [1,2]. In animals these proteins include lamins, which form nuclear intermediate filaments, and growing numbers of NE transmembrane proteins (NETs). Many NETs, such as LEM-domain proteins (see Barton et al., this issue), localize specifically at the inner nuclear membrane (INM) and influence chromatin [3,4]. Other INM NETs, such as SUN-domain proteins, bind within the NE lumen to NETs known as Nesprins in the outer nuclear membrane (ONM), together forming complexes that Link the Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) [5,6]. LINC complexes have major roles in mechanical force transduction to the nucleus [7–9]. Nuclear pore complexes (NPCs), in addition to their canonical roles in nucleocytoplasmic exchange, also have tissue-specific roles [10–13]. For example, specific nucleoporins anchor dynein-dependent movement of the nucleus in developing neurons (see Razafsky and Hodzic, this issue).

Interest in tissue-specific NE proteins arose from the discovery of tissue-specific human diseases known as ‘laminopathies’, which posed a paradox: A-type lamins (encoded by LMNA) are expressed in most differentiated tissues, yet mutations in LMNA can selectively affect striated muscle or cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, restrictive dermopathy, Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy or peripheral neuropathy [14,15]. These distinct pathologies might be explained by selective disruption of tissue-specific partners for A-type lamins. Indeed several lipodystrophy-causing mutations lead to amino acid substitutions mapping to the surface of the Ig-like fold in the tail domain of A-type lamins [16–18]. Other tissue-specific partners might be affected by overexpression of lamin B1 [19] or by mutations in genes coding for widely expressed NETs linked to muscular dystrophy (emerin, nesprin, SUN, LUMA) [20–23], osteopoikilosis (MAN1) [24] or Pelger-Huet anomaly/HEM/Greenberg skeletal dysplasia (LBR) [25,26]. Supporting this concept, loss of the widely expressed LEM-domain protein MAN1 in Drosophila causes tissue-specific defects [27]. Indeed, certain widely expressed NETs have tissue-specific splice variants. For example the LEM-domain protein LAP2/TMPO has at least six experimentally confirmed splice variants [28,29] with developmentally regulated expression in Xenopus [30]. Similarly many Nesprin splice variants are expressed preferentially in specific tissues or during development [31,32]; myogenesis favors shorter splice variants [33], and ovaries express a tissue-specific nesprin-2 epsilon isoform [34]. Significantly expanding the concept of tissue-specificity, a host of potentially disease-relevant new NE membrane proteins is emerging from the field of NE proteomics as discussed below.

Tissue-specific NETs

A- and B-type lamins (LMNA, LMNB1, LMNB2) are differentially expressed in specific cell types with a wide range of functional consequences [35,36]. However this diversity pales in comparison to the number of distinct NET proteins identified so far, starting 15 years ago with a liver-specific NET named UNCL [37]. Since then, several hundred NETs have been identified in multiple proteomic studies [2,38–41], with at least 93 confirmed experimentally (Table 1). Three of these proteomic studies used identical methods to isolate NEs from peripheral blood leukocytes, muscle and liver; this strategy enabled comparisons that revealed only ~15% of NET proteins were shared [2,39,41]. Thus, the expression of most NETs is limited to specific tissues. Other tissue-specific NE proteins that do not have transmembrane spans have also been identified individually as binding partners for lamins in specific tissues such as heart [42].

Table 1. Summary of validated NETs.

Summary of NETs with validated localization at the NE, including tissue-preferential expression and known functions. Tissue specificity is based on comparison of peptide recovery and spectral counts from liver, muscle and leukocyte NEs in [2]. Any NET for which one or more peptide spectra were identified per mass spectroscopy run in a tissue, was considered normally expressed in that tissue, even if it was enriched in another tissue. NETs with 0–1 peptide spectrum per run in specific tissue(s) might be contaminants; in this case AND if another tissue(s) had >10 times more spectra per run, this NET was considered enriched in the other tissue(s). NE targeting of most NETs was confirmed by exogenous expression of tagged constructs; other NETs were localized by antibodies and electron microscopy. NETs annotated ONM or INM were localized by super resolution microscopy. ‘T’ indicates localization at the NE based on resistance to pre-fixation extraction with triton X-100, a classical assay for protein interaction with the nuclear lamina; cytoskeletal-associated ONM proteins may also resist detergent extraction. Not all NETs were tested by triton-resistance. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; PM, plasma membrane; Mito, mitochondria; CID, cardiac intercalated discs. Certain NETs are also listed as ER-localized, in most cases, if the number of spectral counts in NE fractions was <4 times that in microsome fractions. Asterisks indicate NETs that were confirmed (NET46; NET19), but their original hypothetical ORF designation was removed from the NCBI database. References pertain to NE targeting: for functional references see [1].

| Tissue-Specificity | Targeting | Functions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tissue name | INM ONM | other subcellular localizations | Chromatin | Cytoskeleton | Cell Cycle | Signaling | Disease | References |

| liver, blood, and muscle | ||||||||

| P0M121 | PoM | 141 | ||||||

| gp210 | PoM | 142 | ||||||

| NET3, NDC1 | PoM | 40 | ||||||

| LBR | INM | 143 | ||||||

| LAP1 | INM | 144 | ||||||

| LAP2 | INM | 145 | ||||||

| emerin | INM | CID, PM, ER | 50 | |||||

| MAN1 | INM | 146 | ||||||

| SUN1 | INM | 38 | ||||||

| SUN2 | INM | 147 | ||||||

| nesprinl | ONM | 148 | ||||||

| nesprin2 | ONM | 149 | ||||||

| LUMA | 38 | |||||||

| NET13 | 45 | |||||||

| C20orf3 | T | ER | 39 | |||||

| TMEM66 | ur | |||||||

| Tmeml94 | INM | 41 | ||||||

| RHBDD1 | 41 | |||||||

| AADACL1 | INM | ER | 39 | |||||

| METTL7A | INM | ER | 39 | |||||

| DSCD75 | ER | ur | ||||||

| NET8 | T | ER | 40 | |||||

| NET32 | T | 150 | ||||||

| NET24 | ONM | ER | 45 | |||||

| STT3A | INM | ER | 39 | |||||

| NET5, Sampl | INM | 94 | ||||||

| FLJ20254 | INM | ER | 41 | |||||

| NET25 | T | 151 | ||||||

| NET26 | 40 | |||||||

| NET53, nesprin3 | T | 152 | ||||||

| NET56, Dullard | T | ER | 40 | |||||

| NET31 | ONM | 40 | ||||||

| MBOAT5 | INM | 41 | ||||||

| liver enriched | ||||||||

| UNC-50 | 37 | |||||||

| NET4 | ONM | ER | 40 | |||||

| NET33 | INM | ER | 45 | |||||

| NET39 | INM | 45 | ||||||

| EGFR | ER | 45 | ||||||

| NET34 | INM | ER | 45 | |||||

| NET11 | ER | 45 | ||||||

| NET47 | INM | ER | 45 | |||||

| NET55 | INM | 45 | ||||||

| NET62 | 45 | |||||||

| NET46* | INM | 45 | ||||||

| muscle enriched | ||||||||

| TRIC-A | INM | ER | 41 | |||||

| WFS1 | ER | 41 | ||||||

| POPDC2 | ER | 41 | ||||||

| VMA21 | ER | 41 | ||||||

| KLHL31 | 41 | |||||||

| ATP1B4 | 153 | |||||||

| ATP1B1 | ER | 154 | ||||||

| RYR1 | ER | 155 | ||||||

| blood enriched | ||||||||

| HVCN1 | T | ur | ||||||

| LOC55848 | ur | |||||||

| SLC38A10 | ER | ur | ||||||

| LRRC8A | ER | ur | ||||||

| FAM3C | T | ER | ur | |||||

| ABCB1 | 156 | |||||||

| NHE-1 | ER | 157 | ||||||

| InsP 3R | ER | 158 | ||||||

| NET23, STING | T | ER, PM, Mito | 45 | |||||

| LOC84233 | ER | 39 | ||||||

| LOC79415 | INM | 39 | ||||||

| LOC29058 | T | ER | ur | |||||

| SECll-like 3 | INM | 39 | ||||||

| MARCHV | T | ER | 39 | |||||

| NET20 | INM | 45 | ||||||

| NET50 | INM | 45 | ||||||

| AYTL1 | ur | |||||||

| NET45 | ER | 45 | ||||||

| glandular tissues enriched | ||||||||

| nesprin4 | 87 | |||||||

| testis enriched | ||||||||

| SUN3 | 159 | |||||||

| Spag4L, SUN4 | 160 | |||||||

| early development enriched | ||||||||

| NET19* | 161 | |||||||

| fat enriched | ||||||||

| NET29A | INM | 45 | ||||||

| NET29B | T | 84 | ||||||

| migrating P cells, hyp7 precursors and intestinal primordium | ||||||||

| Unc-83 | 44 | |||||||

| liver and blood enriched | ||||||||

| NET59, nicalin | INM | ER | 45 | |||||

| SQSTM1 | T | ur | ||||||

| IAG2 | INM | ER | 39 | |||||

| TAPBPL | T | ER | 39 | |||||

| TMUB1 | ER | ur | ||||||

| Tmeml99 | T | 39 | ||||||

| NET51 | INM | ER | 40 | |||||

| NET9 | T | ER | 150 | |||||

| NET38 | INM | ER | ur | |||||

| liver and muscle enriched | ||||||||

| NET37 | INM | ER | 150 | |||||

| TMTC3 | T | ER | ur | |||||

| NET30 | INM | ER | 45 | |||||

| blood and muscle enriched | ||||||||

| LOC54968 | Mito | 41 | ||||||

| CKAP4 | 41 | |||||||

| TMEM41A | INM | 39 | ||||||

| TMEM109 | T | 39 | ||||||

| nurim | INM | 162 | ||||||

| Non-transmembrane tissue-specific NE proteins | ||||||||

| NPC core components (nucleoporins) | ||||||||

| BS-63 | 60 | |||||||

| Nupl33 | 58 | |||||||

| Nupl55 | 59 | |||||||

| Nup358, RANBP2 | 57 | |||||||

| Nup50 | nucleoplasmic | 163 | ||||||

| Lamins | ||||||||

| Lamin C2 | 164 | |||||||

| Lamin B3 | 165 | |||||||

| heart enriched | ||||||||

| MLIP | 42 | |||||||

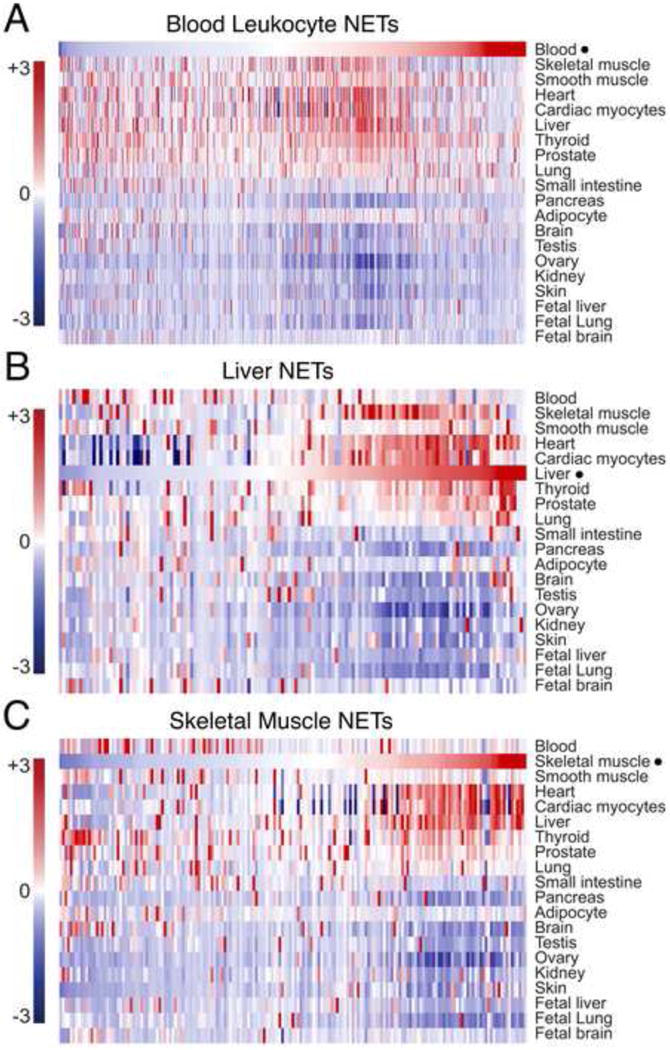

The impact of these newly identified NETs on current thinking about functional diversity at the NE is illustrated in Figure 1. Each plot shows the gene expression distribution across a range of tissues for the NETs isolated from either blood leukocytes [39] (Figure 1A), liver [2] (Figure 1B) or skeletal muscle [41] (Figure 1C). For each tissue only NETs enriched at the NE compared to the ER (an expected contaminant) are shown. Human transcriptome data from BioGPS [43] was transformed to z-scores (a measurement of distance from the mean in standard deviation units) across tissues, and then plotted as a heatmap. Many NETs identified in each tissue were expressed preferentially in that tissue (Figure 1). Some NETs were also expressed in other tissues: for example a splattering of NETs identified in blood leukocytes were also expressed variously in muscle, heart, liver, thyroid, and/or prostate (Figure 1A). For liver the NETs overlapping with other tissues clearly fell into distinct sets for different tissues. For example, a cluster of overlap (red) is observed with skeletal muscle that is clearly distinct from a cluster with thyroid and prostate (Figure 1B). Not surprisingly, many NETs identified in skeletal muscle are also expressed in heart and cardiac myocytes (Figure 1C). Collectively, very few of these NETs are expressed in the pancreas, kidney, brain, ovary or skin, identifying these organs as potentially rich sources of new undiscovered NETs. Among the identified NETs that were also expressed in liver, lung or brain, many were not expressed in fetal versions of those tissues. These findings collectively highlight a major new concept — the high level of tissue-specific or tissue-restricted expression among NE membrane proteins — and reveal an open frontier in biomedical research to define the NET proteomes of important tissues including the brain, pancreas, ovary, kidney and skin.

Figure 1. Tissue specificity of the NE proteome.

Gene expression distribution across a range of tissues, ‘heat-mapped’ for genes encoding NE transmembrane proteins (NETs) identified in proteomic studies of either (A) white blood cells (‘blood leukocytes’) [39], (B) liver [2] or (C) skeletal muscle [41]. Only proteins that were enriched in the NE preparations over an equivalently prepared microsome fraction (5-fold based on peptide spectral counts) are included. This criterion increases the certainty of NET designations, sometimes problematic because the ER is continuous with the ONM and ER proteins are hence legitimate components of NE preparations. Each proteomic dataset was correlated with human transcriptome data from BioGPS [43], transformed to z-scores (a measurement of distance from the mean in standard deviation units) across tissues, and then plotted as a heat-map. Colors indicate probes whose signal was above (red) or below (blue) the average, respectively, for particular tissues. The datasets in A–C were plotted separately but scaled to the same height for presentation.

Tissue-specific import or localization at the NE

Tissue-specificity can also be achieved by selective targeting to the NE. This could be as simple as expressing a tissue-specific partner involved in retention at the INM. For example, C. elegans Unc83 only localizes at the NE when Unc84 is present, though here Unc84 is widely expressed [44]. Several NETs fail to localize at the NE when expressed exogenously in fibroblasts, but target the NE in more differentiated or appropriately specialized cells [45]. WFS1 targets almost exclusively to the NE in muscle [41] but localizes primarily in the ER in other tissues [46]. Indeed, some NETs have variable localizations: LUMA also co-localizes with adherens junctions and myocardial intercalated discs [38,47], and emerin also localizes in the ONM and ER and intercalated discs of cardiomyocytes [48–53]. Differential control of NET protein localization could be achieved by mechanisms ranging from tissue-specific partners to tissue-specific posttranslational modifications. The latter mechanism (differential regulation), interestingly, might be influenced by the tissue-specific control of nucleocytoplasmic transport.

The structure and composition of NPCs, long thought to be uniform [11–13], can vary: about one-third of NPCs have variable subunit stoichiometry [54], and specific nucleoporins show tissue-specific differences in expression. For example the integral membrane nucleoporin gp210, though typically present at NPCs, is absent in certain tissues but is expressed preferentially in muscle [55]. Experimental reduction of gp210 expression during early development specifically affects muscle and neuronal differentiation [56]. Levels of Nup358/RanBP2 increase during myogenesis and alter the architecture of these cytoplasmic NPC filaments as visualized by atomic force microscopy (AFM) [57]. It is tempting to speculate that these changes influence nuclear import or reinforce NPC connections to the cytoskeleton in muscle. Defects in Nup133 cause specific deficits in neural development [58], while mutation of Nup155 in humans or its loss in mice causes atrial fibrillation and sudden death, suggesting a cardiac-specific function of this NPC component [59]. There are also tissue-specific variants of Nup358/RanBP2, POM121 and Nup98/96 [60–62]. Interestingly certain novel tissue-specific NE components identified by proteomics have features characteristic of nucleoporins [63–65]; it will be interesting to determine if they are tissue-specific contributors to NPC function.

The two faces of the NE — tissue-specific impacts on chromatin and the cytoskeleton

Lamins and widely expressed NETs such as LAP2β, LBR and emerin interact with transcriptionally silent chromatin [3,4,66]. For example, LBR binds heterochromatin protein 1 [67]. This interaction helps stabilize peripheral heterochromatin, since LBR knockout in combination with lamin A knockout disrupts and in some cell types completely inverts the spatial distribution of heterochromatin in tissues from nocturnal mammals [68]. NET23/STING, which contributes to the state of chromatin compaction, is also widely expressed, but its levels vary considerably between different cell types. Accordingly, the level of expression of NET23/STING roughly correlates with the extent of chromatin compaction in the various cell types examined [69]. SUN2 binds the chromatin remodeler BRD4 [70]. LAP2β binds histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) [71] and, in co-complex with lamin B1, influences the positioning of several lymphocyte-specific genes [72]. Another such complex may involve LAP1, sumoylation of which influences HDAC4-dependent transcriptional repression of the Cox-2 locus [73]. Emerin, like LAP2, is a ubiquitous NET that can associate with ubiquitous repressors such as HDAC3 or germ cell-less (GCL) [71,74–76]. However, despite GCL being ubiquitous, its reduction in Drosophila and in humans has a tissue-specific effect on the germ line [77,78]. Emerin also interacts with Lmo7, which is relatively tissue-specific [79]. Thus, even widely expressed NETs have the potential to co-function with tissue-specific proteins or respond to tissue-specific control.

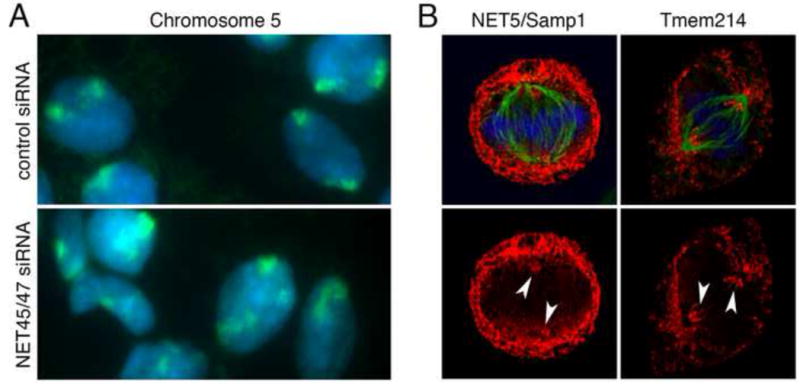

There are now spectacular examples of tissue-specific 3D spatial organization of specific chromosomes and individual genes in the nucleus (reviewed in [3,4,80]). For example, in myoblasts the MyoD locus is maintained near the NE in a zone inaccessible to the TAF3 subunit of the TFIID activating complex; during myotube differentiation the MyoD locus moves to the nuclear interior where it can be activated [81]. Intriguingly this level of regulation can operate in both directions: light stimulation of plant (Arabidopsis) cells repositions the CAB locus from the nuclear interior to the periphery where it becomes active [82]. While some widely expressed NETs contribute to gene repositioning [72], the tissue-specific positioning of genes and chromosomes relative to the NE can also require individual tissue-specific NETs [39,83]. For example, the tendency of chromosome 5 to localize near the NE in liver cells depends on NET45 and NET47 (Figure 2A). NET47 shows extremely preferential expression in liver; NET45 is also expressed preferentially in liver, at levels 50-fold (mRNA) and 20-fold (protein) higher than leukocytes; this enrichment is not reflected in Table 1 due to higher NET45 peptide levels in ER/microsomes [83]. Another NET that affected chromosome positioning, NET29/TMEM120A, is specifically important during adipocyte differentiation [84]. Dynamic ‘tethering’ of silent chromatin, and the roles of individual NETs, are major frontiers in understanding gene regulation and we postulate that tissue-specific NETs will influence the spatial positioning of many developmentally important genes [3,4].

Figure 2. Tissue-specific functions of NETs.

(A) NET45 and NET47, which are highly expressed in liver, function to maintain chromosome 5 near the NE specifically in liver cells. HepG2 liver cells transfected with a control siRNA or siRNA-downregulated for both NET45 and NET47 were visualized by staining DNA with DAPI (blue) and by hybridization with probes that ‘painted’ chromosome 5 (green) as in [83]. Chromosome 5 loses its normal peripheral localization when both liver NETs are absent. (B) Although most NETs are excluded from the base of the microtubule spindles in mitosis when the NE has broken down, NET5/Samp1 and Tmem214 are not [41,94]. Arrowheads indicate NET accumulation around the spindle poles. NET5/Samp1 is also important for the tight centrosome association with the NE; other tissue-specific NETs might also influence cytoskeletal organization or cell polarity.

Tissue-specific diversity is also a feature of LINC complexes [85] and their multifunctional association with different cytoskeletal components [86]. The four Nesprin genes and two Sun-domain genes give rise to multiple isoforms controlled, in part, by tissue-specific alternative mRNA splicing [31], or in the case of Nesprin4 by restricting transcription to limited cell types [87]. LINC complex functions are further modulated by tissue-specific partners. For example NET5/Samp1, which has several isoforms and was expressed in only 3 of 11 tissues tested [83], and the widely expressed diaphanous formin, FHOD1, both contribute to actin-dependent nuclear migration [88,89] mediated by transmembrane actin-associated nuclear (TAN) lines, which include the ‘giant’ isoform of nesprin-2 (nesprin-2G) and SUN2 [90–92]. NET5/Samp1 also interacts with lamin A and SUN1 [93]. NET5/Samp1 contributes to centrosome positioning during interphase, and accumulates at the spindle base during mitosis [94] (Figure 2B). Centrosome positioning is critical to orient the nucleus and cytoskeleton in highly polarized cell types such as neurons, polarized epithelia or during antigen presentation in immune cells. Certain novel tissue-specific NETs also accumulate at the spindle base (Figure 2B), or co-localize with microtubules at the nuclear surface [41]. The unexpectedly large number of novel partners for SUN-domain proteins discovered in plants suggests an even wider range of functions [95].

Distinct partners for LINC complexes may also explain their ability to interact with high-tension versus low-tension actin filaments at the NE [8] and influence mechanotransduction signalling in specific cell types [7–9]. The transcription factor megakaryoblastic leukaemia 1, which responds to mechanical stress [96], is functionally impaired in cells from Lmna−/− mice suggesting it functions downstream of LINC- and lamin A-dependent force transduction [97]. Other NETs involved in signalling cascades include emerin (e.g., β-catenin signalling) [98], MAN1 (e.g., rSmad-mediated and TGF-β signalling) [24,99–101] and NET25/LEM2 (e.g., ERK signalling) [102]. Interestingly, NET25/LEM2 is widely expressed but is strongly induced in muscle; consistent with this pattern, heterozygous knockout mice have a muscle-specific defect whereas homozygous knockouts have gross developmental defects across tissues [103]. MAP kinase signalling is affected by loss of emerin [104] or lamin A/C [105]— another layer of tissue-specific control involving NE proteins. Finally, signalling is influenced by tissue-specific NETs. For example NET39 is liver-enriched (based on 5-fold enrichment over the ER/microsome fraction in Table 1), but is also expressed in muscle where it affects mTOR signaling [106]. Similarly the blood and liver-enriched NET45/DAK is present and affects dsRNA innate antiviral signaling in tissue culture cells [107].

The NE as a tissue-specific interface

NE proteins– ubiquitous and tissue-specific— collectively define the functionality of the nucleus in each cell type and may be particularly critical in certain tissues or at specific times. For example, myogenic differentiation requires LINC complexes [7], and lamin A variants linked to striated muscle disease have defects in LINC complex-dependent nuclear positioning [108]. LINC complexes are also particularly important for nuclear migration during retinal development [109,110], centrosome function during neurogenesis [111] and glutamate receptor density at neuromuscular junctions [112], and may co-function with lamin B2 during neuronal migration [113].

The ratios of specific A- and B-type lamins are major determinants of cell type-specific mechanics that dictate whether differentiated blood cells can exit the bone marrow [114]. Not surprisingly, the nucleoskeleton is dramatically reorganized during adipogenesis [115]. Specific lamins also support the function of specific transcription regulators, including the muscle transcription factor myoD [116,117] and the cell cycle and differentiation regulator pRb [118–120]. Several tissue-specific NETs also affect cell cycle regulation [121], a potentially novel contribution to tissue-specific pathology.

In one case, the mechanism of tissue-specificity is clear: nesprin4 is expressed in very few tissues including the cochlea, and nesprin4 gene mutations cause high frequency hearing loss [87,122]. However, most NE-linked diseases are caused by mutations in genes encoding widely expressed proteins. These proteins might disrupt binding to a tissue-specific partner(s), leading to pathology. The concept that NE proteins form functional complexes that may include tissue-specific partners is underscored by human genetics, since EDMD-like phenotypes can be caused by mutations in the genes encoding either lamin A/C, emerin, nesprin1, nesprin2, SUN1, SUN2 or FLH1, all of which interact directly or indirectly [20,22,23,123,124]. The FLH1 and nesprin disease variants are both linked to expression of a specific splice variant [23,124]. LINC complexes also appear to function tissue-specifically. For example, nesprin interactions with desmin, an important muscle-specific intermediate filament protein, may underlie its clinical manifestation as muscular dystrophy [125]. Alternatively, the nesprin ANC-1 interacts with the signaling protein RPM-1 in C. elegans brains and then influences β-catenin signaling during neural development [126]. In contrast, the mammalian nesprin-2 directly interacts with α-catenin and is a positive regulator of Wnt signaling in keratinocytes, COS-7 and HaCaT cells [127]. LINC complex interactions with dystroglycan are important for maintaining the positioning and connectivity of lumbar neurons to avoid breaking their connections to the muscle during muscle contraction [128]. The NETs LAP1 and emerin also interact; depleting either one causes muscular dystrophy while depleting both generates a more severe phenotype [129].

Novel NETs implicated in tissue-specific disease

Several tissue-specific NETs are linked to disease. Mutations in the genes encoding VMA21 and Tmem70, both identified in isolated muscle NEs, respectively cause human myopathy [130] and neonatal encephalocardiomyopathy [131]. WFS1 is preferentially expressed in muscle and retina [43] and mutations in its gene cause Wolfram syndrome, characterized by optic atrophy, deafness and/or diabetes [132–134]. Mutations in LRRC8A, encoding a leukocyte-specific NET, specifically inhibit B-cell development [135]. Other tissue-specific NETs show promise as disease candidates. For example the NET Tmem38A is expressed in both smooth and skeletal muscle [2,41] and its depletion in mice affects smooth muscle causing hypertension [136] and skeletal muscle where the explanted muscle exhibits stronger initial contractile force but rapidly fatigues [137]. Depletion of another muscle-specific NET, Popdc2, leads to mice with stress-induced bradycardia [138], suggesting roles in cardiac muscle pathology.

Future outlook

Tissue-specific NETs are exciting new pieces of the laminopathy puzzle. We estimate that over half of all NETs are still unidentified in mammals, and, as many are not conserved in evolution [1], most NETs are unidentified in lower organisms. The 598 identified mammalian NETs [2] are enriched in their tissues of origin and certain other tissues (Figure 1), whereas distinctive unexplored tissues such as skin and brain likely harbor many novel tissue-specific NETs. Furthermore, very little is known about most of the tissue-specific NETs identified thus far. Only ~10% of NETs identified by proteomics have been tested for NE targeting [2]. Unfortunately, domain or family resemblances have little predictive value, since several validated NETs appear to be splice variants of proteins that function in the cytoplasm, mitochondria or plasma membrane. For example the Na,K-ATPase beta m subunit, which normally functions in a larger complex as a Na+/K+ translocating ATPase at the surface of most cells, can also localize independently of the rest of the complex at the NE of neonatal skeletal muscle and C2C12 cells where it functions in transcriptional regulation [139]. Tissue-specific NETs may have arisen during evolution by amplification and adaptation of cytoplasmic proteins for secondary nuclear functions, as proposed [139]; alternatively, some ancestral proteins may have functioned at the NE as proposed for intermediate filaments [140]. What is clear is that tissue-specificity of the NE arises in many ways and makes this organelle critical for integrating genome function in specific cell types.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jose I. de las Heras for generating the HEAT maps in Figure 1, Nikolaj Zuleger for images used in Figure 2 and Michael I. Robson for assistance with figure preparation. ECS is supported by Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship 095209 and Centre Grant 092076; HJW is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01AR048997, R01HD070713, R56NS059352), Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA 294537) and Los Angeles Thoracic and Cardiovascular Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

+ of special interest

++ of outstanding interest

- 1++.de Las Heras JI, Meinke P, Batrakou DG, Srsen V, Zuleger N, Kerr AR, Schirmer EC. Tissue specificity in the nuclear envelope supports its functional complexity. Nucleus. 2013;4:460–477. doi: 10.4161/nucl.26872. An extensive analysis of potential evolutionary conservation of all NETs identified by proteomics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2++.Korfali N, Wilkie GS, Swanson SK, Srsen V, de Las Heras J, Batrakou DG, Malik P, Zuleger N, Kerr AR, Florens L, et al. The nuclear envelope proteome differs notably between tissues. Nucleus. 2012;3:552–564. doi: 10.4161/nucl.22257. This comparison of NET proteomes isolated from different tissues using identical methods revealed that the vast majority of NET proteins are tissue-specific. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong X, Luperchio TR, Reddy KL. NET gains and losses: the role of changing nuclear envelope proteomes in genome regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;28:105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuleger N, Robson MI, Schirmer EC. The nuclear envelope as a chromatin organizer. Nucleus. 2011;2:339–349. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.5.17846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crisp M, Liu Q, Roux K, Rattner JB, Shanahan C, Burke B, Stahl PD, Hodzic D. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:41–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6+.Osorio DS, Gomes ER. Connecting the nucleus to the cytoskeleton for nuclear positioning and cell migration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;773:505–520. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_23. An excellent review of TAN lines, their role in nuclear migration and the contribution of tissue-specific aspects of the complex. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brosig M, Ferralli J, Gelman L, Chiquet M, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Interfering with the connection between the nucleus and the cytoskeleton affects nuclear rotation, mechanotransduction and myogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1717–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8++.Chambliss AB, Khatau SB, Erdenberger N, Robinson DK, Hodzic D, Longmore GD, Wirtz D. The LINC-anchored actin cap connects the extracellular milieu to the nucleus for ultrafast mechanotransduction. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1087. doi: 10.1038/srep01087. This study identified two distinct types of actin fibers, high-tension versus low-tension, connected to the NE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9++.Guilluy C, Osborne LD, Van Landeghem L, Sharek L, Superfine R, Garcia-Mata R, Burridge K. Isolated nuclei adapt to force and reveal a mechanotransduction pathway in the nucleus. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ncb2927. Nuclear stiffness adapts to forces exerted on the nucleus with corresponding changes in phosphorylation of the NET protein, emerin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raices M, D’Angelo MA. Nuclear pore complex composition: a new regulator of tissue-specific and developmental functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:687–699. doi: 10.1038/nrm3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronshaw J, Krutchinsky A, Zhang W, Chait B, Matunis M. Proteomic analysis of the mammalian nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:915–927. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeGrasse JA, DuBois KN, Devos D, Siegel TN, Sali A, Field MC, Rout MP, Chait BT. Evidence for a shared nuclear pore complex architecture that is conserved from the last common eukaryotic ancestor. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:2119–2130. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900038-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y, Chait BT. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:635–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonne G, Quijano-Roy S. Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, laminopathies, and other nuclear envelopathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;113:1367–1376. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59565-2.00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15+.Worman HJ, Dauer WT. The nuclear envelope: an intriguing focal point for neurogenetic disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11:764–772. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0296-8. An excellent and comprehensive review of NE diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhe-Paganon S, Werner ED, Chi Y-I, Shoelson SE. Structure of the globular tail of nuclear lamin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17381–17384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krimm I, Ostlund C, Gilquin B, Couprie J, Hossenlopp P, Mornon J, Bonne G, Courvalin J, Worman H, Zinn-Justin S. The Ig-like structure of the C-terminal domain of lamin A/C, mutated in muscular dystrophies, cardiomyopathy, and partial lipodystrophy. Structure (Camb) 2002;10:811–823. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00777-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scharner J, Lu HC, Fraternali F, Ellis JA, Zammit PS. Mapping disease-related missense mutations in the immunoglobulin-like fold domain of lamin A/C reveals novel genotype-phenotype associations for laminopathies. Proteins. 2014;82:904–915. doi: 10.1002/prot.24465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padiath QS, Saigoh K, Schiffmann R, Asahara H, Yamada T, Koeppen A, Hogan K, Ptacek LJ, Fu YH. Lamin B1 duplications cause autosomal dominant leukodystrophy. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1114–1123. doi: 10.1038/ng1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bione S, Maestrini E, Rivella S, Mancini M, Regis S, Romeo G, Toniolo D. Identification of a novel X-linked gene responsible for Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1994;8:323–327. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang WC, Mitsuhashi H, Keduka E, Nonaka I, Noguchi S, Nishino I, Hayashi YK. TMEM43 mutations in Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy-related myopathy. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:1005–1013. doi: 10.1002/ana.22338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22+.Meinke P, Mattioli E, Haque F, Antoku S, Columbaro M, Straatman KR, Worman HJ, Gundersen GG, Lattanzi G, Wehnert M, et al. Muscular dystrophy-associated SUN1 and SUN2 variants disrupt nuclear-cytoskeletal connections and myonuclear organization. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004605. This study demonstrated that mutations in the genes encoding SUN proteins can cause variants of EDMD and, in conjunction with disease alleles in other genes, can act as modifiers that greatly increase disease severity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Q, Bethmann C, Worth NF, Davies JD, Wasner C, Feuer A, Ragnauth CD, Yi Q, Mellad JA, Warren DT, et al. Nesprin-1 and -2 are involved in the pathogenesis of Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy and are critical for nuclear envelope integrity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2816–2833. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hellemans J, Preobrazhenska O, Willaert A, Debeer P, Verdonk PC, Costa T, Janssens K, Menten B, Van Roy N, Vermeulen SJ, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in LEMD3 result in osteopoikilosis, Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome and melorheostosis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/ng1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann K, Dreger C, Olins A, Olins D, Shultz L, Lucke B, Karl H, Kaps R, Muller D, Vaya A, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the lamin B receptor produce an altered nuclear morphology in granulocytes (Pelger-Huet anomaly. Nat Genet. 2002;31:410–414. doi: 10.1038/ng925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waterham H, Koster J, Mooyer P, Noort GG, Kelley R, Wilcox W, Wanders R, Hennekam R, Oosterwijk J. Autosomal Recessive HEM/Greenberg Skeletal Dysplasia Is Caused by 3beta-Hydroxysterol Delta14-Reductase Deficiency Due to Mutations in the Lamin B Receptor Gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1013–1017. doi: 10.1086/373938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27+.Pinto BS, Wilmington SR, Hornick EE, Wallrath LL, Geyer PK. Tissue-specific defects are caused by loss of the Drosophila MAN1 LEM domain protein. Genetics. 2008;180:133–145. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.091371. Genetic demonstration that deletion of a widely expressed NET can yield tissue-specific defects. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger R, Theodor L, Shoham J, Gokkel E, Brok-Simoni F, Avraham KB, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Rechavi G, Simon AJ. The characterization and localization of the mouse thymopoietin/lamina- associated polypeptide 2 gene and its alternatively spliced products. Genome Res. 1996;6:361–370. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.5.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris CA, Andryuk PJ, Cline S, Chan HK, Natarajan A, Siekierka JJ, Goldstein G. Three distinct human thymopoietins are derived from alternatively spliced mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6283–6287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoft VK, Beauvais AJ, Lang C, Gajewski A, Prufert K, Winkler C, Akimenko MA, Paulin-Levasseur M, Krohne G. The lamina-associated polypeptide 2 (LAP2) isoforms beta, gamma and omega of zebrafish: developmental expression and behavior during the cell cycle. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2505–2517. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31+.Duong NT, Morris GE, Lam le T, Zhang Q, Sewry CA, Shanahan CM, Holt I. Nesprins: tissue-specific expression of epsilon and other short isoforms. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094380. Some splice variants of widely expressed nesprins are in fact tissue-specific. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32+.Rajgor D, Mellad JA, Autore F, Zhang Q, Shanahan CM. Multiple novel nesprin-1 and nesprin-2 variants act as versatile tissue-specific intracellular scaffolds. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040098. The most comprehensive bioinformatic characterization of tissue-specific isoforms of nesprins; cloning and testing of several isoforms revealed targeting to multiple cytoskeletal structures. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Randles KN, Lam le T, Sewry CA, Puckelwartz M, Furling D, Wehnert M, McNally EM, Morris GE. Nesprins, but not sun proteins, switch isoforms at the nuclear envelope during muscle development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:998–1009. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lam le T, Bohm SV, Roberts RG, Morris GE. Nesprin-2 epsilon: a novel nesprin isoform expressed in human ovary and Ntera-2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke B, Stewart CL. The nuclear lamins: flexibility in function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuela N, Bar DZ, Gruenbaum Y. Lamins in development, tissue maintenance and stress. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:1070–1078. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37++.Fitzgerald J, Kennedy D, Viseshakul N, Cohen BN, Mattick J, Bateman JF, Forsayeth JR. UNCL, the mammalian homologue of UNC-50, is an inner nuclear membrane RNA-binding protein. Brain Res. 2000;877:110–123. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02692-5. First report of a NET that is actually tissue-specific in expression. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38+.Dreger M, Bengtsson L, Schoneberg T, Otto H, Hucho F. Nuclear envelope proteomics: novel integral membrane proteins of the inner nuclear membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11943–11948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211201898. The first proteomic study of isolated NEs from cultured cells. Extracted bands from 2D gels revealed some novel proteins, but far fewer than later studies that used natural tissues as sources and directly analyzed fractions by LC/LC/MS/MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39++.Korfali N, Wilkie GS, Swanson SK, Srsen V, Batrakou DG, Fairley EA, Malik P, Zuleger N, Goncharevich A, de Las Heras J, et al. The leukocyte nuclear envelope proteome varies with cell activation and contains novel transmembrane proteins that affect genome architecture. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2571–2585. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.002915. This proteomic analysis of isolated blood NETs revealed many blood-specific NETs not found in the earlier study of liver, and introduced a mass spectrometry strategy that improved the identification of membrane proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40+.Schirmer EC, Florens L, Guan T, Yates JRr, Gerace L. Nuclear membrane proteins with potential disease links found by subtractive proteomics. Science. 2003;301:1380–1382. doi: 10.1126/science.1088176. The first NE proteomics study to use both LC/LC/MS/MS and natural tissue (liver). This study found many more proteins than Dreger et al (2001), but fewer than Korfali et al (2012) [ref 2], who identified many additional minor proteins by using multiple replicate runs and by performing sequential digests to identify peptides from more hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41++.Wilkie GS, Korfali N, Swanson SK, Malik P, Srsen V, Batrakou DG, de las Heras J, Zuleger N, Kerr AR, Florens L, et al. Several novel nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins identified in skeletal muscle have cytoskeletal associations. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110 003129. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003129. Proteomics of isolated muscle NEs using the improved approaches reveals many muscle-specific proteins not found in other studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42+.Ahmady E, Deeke SA, Rabaa S, Kouri L, Kenney L, Stewart AF, Burgon PG. Identification of a novel muscle A-type lamin-interacting protein (MLIP) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19702–19713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.165548. Unique identification of a lamin-interacting NET from heart. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu C, Orozco C, Boyer J, Leglise M, Goodale J, Batalov S, Hodge CL, Haase J, Janes J, Huss JW, 3rd, et al. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R130. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44+.Starr DA, Hermann GJ, Malone CJ, Fixsen W, Priess JR, Horvitz HR, Han M. unc-83 encodes a novel component of the nuclear envelope and is essential for proper nuclear migration. Development. 2001;128:5039–5050. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5039. Clear demonstration that some NETs depend on other NE components for their targeting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45+.Malik P, Korfali N, Srsen V, Lazou V, Batrakou DG, Zuleger N, Kavanagh DM, Wilkie GS, Goldberg MW, Schirmer EC. Cell-specific and lamin-dependent targeting of novel transmembrane proteins in the nuclear envelope. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:1353–1369. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0257-2. Testing of a large set of NETs showed that many are NE-localized only in certain cell types. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeda K, Inoue H, Tanizawa Y, Matsuzaki Y, Oba J, Watanabe Y, Shinoda K, Oka Y. WFS1 (Wolfram syndrome 1) gene product: predominant subcellular localization to endoplasmic reticulum in cultured cells and neuronal expression in rat brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:477–484. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franke WW, Dorflinger Y, Kuhn C, Zimbelmann R, Winter-Simanowski S, Frey N, Heid H. Protein LUMA is a cytoplasmic plaque constituent of various epithelial adherens junctions and composite junctions of myocardial intercalated disks: a unifying finding for cell biology and cardiology. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;357:159–172. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1865-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cartegni L, di Barletta MR, Barresi R, Squarzoni S, Sabatelli P, Maraldi N, Mora M, Di Blasi C, Cornelio F, Merlini L, et al. Heart-specific localization of emerin: new insights into Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2257–2264. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.13.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lattanzi G, Ognibene A, Sabatelli P, Capanni C, Toniolo D, Columbaro M, Santi S, Riccio M, Merlini L, Maraldi NM, et al. Emerin expression at the early stages of myogenic differentiation. Differentiation. 2000;66:208–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2000.660407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manilal S, Nguyen TM, Sewry CA, Morris GE. The Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy protein, emerin, is a nuclear membrane protein. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:801–808. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salpingidou G, Smertenko A, Hausmanowa-Petrucewicz I, Hussey PJ, Hutchison CJ. A novel role for the nuclear membrane protein emerin in association of the centrosome to the outer nuclear membrane. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:897–904. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Squarzoni S, Sabatelli P, Capanni C, Petrini S, Ognibene A, Toniolo D, Cobianchi F, Zauli G, Bassini A, Baracca A, et al. Emerin presence in platelets. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100:291–298. doi: 10.1007/s004019900169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wheeler MA, Warley A, Roberts RG, Ehler E, Ellis JA. Identification of an emerin-beta-catenin complex in the heart important for intercalated disc architecture and beta-catenin localisation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:781–796. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0219-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54++.Ori A, Banterle N, Iskar M, Andres-Pons A, Escher C, Khanh Bui H, Sparks L, Solis-Mezarino V, Rinner O, Bork P, et al. Cell type-specific nuclear pores: a case in point for context-dependent stoichiometry of molecular machines. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:648. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.4. Showed that individual NPC components can vary considerably in relative stoichiometry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55++.Olsson M, Scheele S, Ekblom P. Limited expression of nuclear pore membrane glycoprotein 210 in cell lines and tissues suggests cell-type specific nuclear pores in metazoans. Exp Cell Res. 2004;292:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.09.014. Demonstration of tissue-restricted expression of a core NPC component. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56++.D’Angelo MA, Gomez-Cavazos JS, Mei A, Lackner DH, Hetzer MW. A change in nuclear pore complex composition regulates cell differentiation. Dev Cell. 2012;22:446–458. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.021. Tissue-specific NPC proteins can play important roles during development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57+.Asally M, Yasuda Y, Oka M, Otsuka S, Yoshimura SH, Takeyasu K, Yoneda Y. Nup358, a nucleoporin, functions as a key determinant of the nuclear pore complex structure remodeling during skeletal myogenesis. FEBS J. 2011;278:610–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07982.x. A widely expressed NPC protein can have tissue-specific roles. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58++.Lupu F, Alves A, Anderson K, Doye V, Lacy E. Nuclear pore composition regulates neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation in the mouse embryo. Dev Cell. 2008;14:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.011. Loss of a ubiquitous NPC protein causes tissue-specific developmental defects. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59++.Zhang X, Chen S, Yoo S, Chakrabarti S, Zhang T, Ke T, Oberti C, Yong SL, Fang F, Li L, et al. Mutation in nuclear pore component NUP155 leads to atrial fibrillation and early sudden cardiac death. Cell. 2008;135:1017–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.022. Loss of a ubiquitous NPC protein causes tissue-specific developmental defects. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60+.Cai Y, Gao Y, Sheng Q, Miao S, Cui X, Wang L, Zong S, Koide SS. Characterization and potential function of a novel testis-specific nucleoporin BS-63. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;61:126–134. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1139. Early report of a tissue-specific NPC component. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coy JF, Wiemann S, Bechmann I, Bachner D, Nitsch R, Kretz O, Christiansen H, Poustka A. Pore membrane and/or filament interacting like protein 1 (POMFIL1) is predominantly expressed in the nervous system and encodes different protein isoforms. Gene. 2002;290:73–94. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Enninga J, Levy DE, Blobel G, Fontoura BM. Role of nucleoporin induction in releasing an mRNA nuclear export block. Science. 2002;295:1523–1525. doi: 10.1126/science.1067861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Batrakou DG, Kerr AR, Schirmer EC. Comparative proteomic analyses of the nuclear envelope and pore complex suggests a wide range of heretofore unexpected functions. J Proteomics. 2008;72:56–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64+.Kerr AR, Schirmer EC. FG repeats facilitate integral protein trafficking to the inner nuclear membrane. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:557–559. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.5.16052. High throughput bioinformatic analysis identifies shared characteristics among hundreds of NETs from different tissues. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zuleger N, Kelly DA, Richardson AC, Kerr AR, Goldberg MW, Goryachev AB, Schirmer EC. System analysis shows distinct mechanisms and common principles of nuclear envelope protein dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:109–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Talamas JA, Capelson M. Nuclear envelope and genome interactions in cell fate. Front Genet. 2015;6:95. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67++.Ye Q, Worman HJ. Interaction between an integral protein of the nuclear envelope inner membrane and human chromodomain proteins homologous to Drosophila HP1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14653–14656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14653. First specific heterochromatin protein found to directly interact with a NET. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68++.Solovei I, Wang AS, Thanisch K, Schmidt CS, Krebs S, Zwerger M, Cohen TV, Devys D, Foisner R, Peichl L, et al. LBR and Lamin A/C Sequentially Tether Peripheral Heterochromatin and Inversely Regulate Differentiation. Cell. 2013;152:584–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.009. One NET (LBR) and lamin A together are largely responsible for global patterns of heterochromatin distribution; this is especially important in the retina of nocturnal animals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69+.Malik P, Zuleger N, de las Heras JI, Saiz-Ros N, Makarov AA, Lazou V, Meinke P, Waterfall M, Kelly DA, Schirmer EC. NET23/STING promotes chromatin compaction from the nuclear envelope. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111851. Although widely expressed, NET23 can have tissue-specific effects based on its expression level as the degree of chromatin compaction correlates with the level of expression in different cell types. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70+.Alsarraj J, Faraji F, Geiger TR, Mattaini KR, Williams M, Wu J, Ha NH, Merlino T, Walker RC, Bosley AD, et al. BRD4 short isoform interacts with RRP1B, SIPA1 and components of the LINC complex at the inner face of the nuclear membrane. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080746. A chromatin remodeller can interact with NE-spanning LINC complexes and could potentially be involved in mediating chromatin changes in response to mechanical force. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Somech R, Shaklai S, Geller O, Amariglio N, Simon AJ, Rechavi G, Gal-Yam EN. The nuclear-envelope protein and transcriptional repressor LAP2beta interacts with HDAC3 at the nuclear periphery, and induces histone H4 deacetylation. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4017–4025. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zullo JM, Demarco IA, Pique-Regi R, Gaffney DJ, Epstein CB, Spooner CJ, Luperchio TR, Bernstein BE, Pritchard JK, Reddy KL, et al. DNA sequence-dependent compartmentalization and silencing of chromatin at the nuclear lamina. Cell. 2012;149:1474–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang WL, Lee YC, Yang WM, Chang WC, Wang JM. Sumoylation of LAP1 is involved in the HDAC4-mediated repression of COX-2 transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6066–6079. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Demmerle J, Koch AJ, Holaska JM. Emerin and histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) cooperatively regulate expression and nuclear positions of MyoD, Myf5, and Pax7 genes during myogenesis. Chromosome Res. 2013;21:765–779. doi: 10.1007/s10577-013-9381-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Holaska JM, Lee K, Kowalski AK, Wilson KL. Transcriptional repressor germ cellless (GCL) and barrier to autointegration factor (BAF) compete for binding to emerin in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6969–6975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nili E, Cojocaru GS, Kalma Y, Ginsberg D, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Berger R, Shaklai S, Amariglio N, et al. Nuclear membrane protein LAP2beta mediates transcriptional repression alone and together with its binding partner GCL (germ-cell-less) J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3297–3307. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.18.3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jongens TA, Hay B, Jan LY, Jan YN. The germ cell-less gene product: a posteriorly localized component necessary for germ cell development in Drosophila. Cell. 1992;70:569–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90427-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kleiman SE, Yogev L, Gal-Yam EN, Hauser R, Gamzu R, Botchan A, Paz G, Yavetz H, Maymon BB, Schreiber L, et al. Reduced human germ cell-less (HGCL) expression in azoospermic men with severe germinal cell impairment. J Androl. 2003;24:670–675. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79+.Holaska JM, Rais-Bahrami S, Wilson KL. Lmo7 is an emerin-binding protein that regulates the transcription of emerin and many other muscle-relevant genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3459–3472. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl423. Tissue-specific functionality of a transcription factor is mediated by interaction with a widely expressed NET. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bridger JM, Arican-Gotkas HD, Foster HA, Godwin LS, Harvey A, Kill IR, Knight M, Mehta IS, Ahmed MH. The non-random repositioning of whole chromosomes and individual gene loci in interphase nuclei and its relevance in disease, infection, aging, and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;773:263–279. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81++.Yao J, Fetter RD, Hu P, Betzig E, Tjian R. Subnuclear segregation of genes and core promoter factors in myogenesis. Genes Dev. 2011;25:569–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.2021411. Demonstration that repositioning of a developmentally regulated gene correlates with transcriptional activation and changes in epigenetic regulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Feng CM, Qiu Y, Van Buskirk EK, Yang EJ, Chen M. Light-regulated gene repositioning in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3027. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83++.Zuleger N, Boyle S, Kelly DA, de Las Heras JI, Lazou V, Korfali N, Batrakou DG, Randles KN, Morris GE, Harrison DJ, et al. Specific nuclear envelope transmembrane proteins can promote the location of chromosomes to and from the nuclear periphery. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-2-r14. First evidence of direct functional involvement of tissue-specific NETs in establishing particular tissue-specific patterns of spatial genome organization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84++.Batrakou DG, de Las Heras JI, Czapiewski R, Mouras R, Schirmer EC. TMEM120A and B: Nuclear Envelope Transmembrane Proteins Important for Adipocyte Differentiation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127712. Loss of a tissue-specific NET severely disrupts tissue differentiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sosa BA, Rothballer A, Kutay U, Schwartz TU. LINC complexes form by binding of three KASH peptides to domain interfaces of trimeric SUN proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1035–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86+.Chang W, Worman HJ, Gundersen GG. Anchoring and accessorizing the LINC complex. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:11–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201409047. Detailed review of partners that influence functionality of the universal LINC complex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roux KJ, Crisp ML, Liu Q, Kim D, Kozlov S, Stewart CL, Burke B. Nesprin 4 is an outer nuclear membrane protein that can induce kinesin-mediated cell polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2194–2199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808602106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88++.Borrego-Pinto J, Jegou T, Osorio DS, Aurade F, Gorjanacz M, Koch B, Mattaj IW, Gomes ER. Samp1 is a component of TAN lines and is required for nuclear movement. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1099–1105. doi: 10.1242/jcs.087049. Clear demonstration that a relatively tissue-specific NET contributes functionally to the universal LINC complex. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89+.Kutscheidt S, Zhu R, Antoku S, Luxton GW, Stagljar I, Fackler OT, Gundersen GG. FHOD1 interaction with nesprin-2G mediates TAN line formation and nuclear movement. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:708–715. doi: 10.1038/ncb2981. Further specification of LINC complex functions by additional partner proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gomes ER, Jani S, Gundersen GG. Nuclear movement regulated by Cdc42, MRCK, myosin, and actin flow establishes MTOC polarization in migrating cells. Cell. 2005;121:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91++.Luxton GW, Gomes ER, Folker ES, Vintinner E, Gundersen GG. Linear arrays of nuclear envelope proteins harness retrograde actin flow for nuclear movement. Science. 2010;329:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1189072. Definition of TAN lines and their role in nuclear positioning. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Luxton GW, Gomes ER, Folker ES, Worman HJ, Gundersen GG. TAN lines: a novel nuclear envelope structure involved in nuclear positioning. Nucleus. 2011;2:173–181. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.3.16243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93+.Gudise S, Figueroa RA, Lindberg R, Larsson V, Hallberg E. Samp1 is functionally associated with the LINC complex and A-type lamina networks. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2077–2085. doi: 10.1242/jcs.078923. First demonstration that a NET with tissue-restricted variants interacts with the LINC complex. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94++.Buch C, Lindberg R, Figueroa R, Gudise S, Onischenko E, Hallberg E. An integral protein of the inner nuclear membrane localizes to the mitotic spindle in mammalian cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2100–2107. doi: 10.1242/jcs.047373. Evidence that NET5/Samp1, expression of which is tissue-restricted, interacts with the mitotic spindle. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95++.Zhou X, Graumann K, Wirthmueller L, Jones JD, Meier I. Identification of unique SUN-interacting nuclear envelope proteins with diverse functions in plants. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:677–692. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401138. Large-scale identification of binding partners for SUN-domain proteins in plants, indicating wide functionality. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Iyer KV, Pulford S, Mogilner A, Shivashankar GV. Mechanical activation of cells induces chromatin remodeling preceding MKL nuclear transport. Biophys J. 2012;103:1416–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97++.Ho CY, Jaalouk DE, Vartiainen MK, Lammerding J. Lamin A/C and emerin regulate MKL1-SRF activity by modulating actin dynamics. Nature. 2013;497:507–511. doi: 10.1038/nature12105. A mechanosensitive signaling cascade linked to nucleoskeletal connections. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Markiewicz E, Tilgner K, Barker N, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Dorobek M, Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I, Ramaekers FC, Broers JL, Blankesteijn WM, et al. The inner nuclear membrane protein emerin regulates beta-catenin activity by restricting its accumulation in the nucleus. EMBO J. 2006;25:3275–3285. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lin F, Morrison JM, Wu W, Worman HJ. MAN1, an integral protein of the inner nuclear membrane, binds Smad2 and Smad3 and antagonizes transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:437–445. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Osada S, Ohmori SY, Taira M. XMAN1, an inner nuclear membrane protein, antagonizes BMP signaling by interacting with Smad1 in Xenopus embryos. Development. 2003;130:1783–1794. doi: 10.1242/dev.00401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pan D, Estevez-Salmeron LD, Stroschein SL, Zhu X, He J, Zhou S, Luo K. The integral inner nuclear membrane protein MAN1 physically interacts with the R-Smad proteins to repress signaling by the transforming growth factor-{beta} superfamily of cytokines. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15992–16001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huber MD, Guan T, Gerace L. Overlapping functions of nuclear envelope proteins NET25 (Lem2) and emerin in regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in myoblast differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5718–5728. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00270-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103++.Tapia O, Fong LG, Huber MD, Young SG, Gerace L. Nuclear envelope protein Lem2 is required for mouse development and regulates MAP and AKT kinases. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116196. Mouse knockout of widely expressed NET shows global effects in the homozygote, but tissue-specific effects in the heterozygote correlating with the tissue where it is highest expressed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104++.Muchir A, Pavlidis P, Bonne G, Hayashi YK, Worman HJ. Activation of MAPK in hearts of EMD null mice: similarities between mouse models of X-linked and autosomal dominant Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1884–1895. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm137. Identification of heart-specific signaling cascade linked to emerin that may explain cardiomyopathy linked to EDMD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Muchir A, Wu W, Worman HJ. Reduced expression of A-type lamins and emerin activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase in cultured cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liu GH, Guan T, Datta K, Coppinger J, Yates J, 3rd, Gerace L. Regulation of myoblast differentiation by the nuclear envelope protein NET39. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5800–5812. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00684-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Diao F, Li S, Tian Y, Zhang M, Xu LG, Zhang Y, Wang RP, Chen D, Zhai Z, Zhong B, et al. Negative regulation of MDA5- but not RIG-I-mediated innate antiviral signaling by the dihydroxyacetone kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11706–11711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700544104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108++.Folker ES, Ostlund C, Luxton GW, Worman HJ, Gundersen GG. Lamin A variants that cause striated muscle disease are defective in anchoring transmembrane actin-associated nuclear lines for nuclear movement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:131–136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000824108. Disease-associated lamin mutations alter NE interactions with cytoplasmic filaments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109++.Razafsky D, Blecher N, Markov A, Stewart-Hutchinson PJ, Hodzic D. LINC complexes mediate the positioning of cone photoreceptor nuclei in mouse retina. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047180. Tissue-specific functionality for the LINC complex based on individual cell type requirements. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110++.Yu J, Lei K, Zhou M, Craft CM, Xu G, Xu T, Zhuang Y, Xu R, Han M. KASH protein Syne-2/Nesprin-2 and SUN proteins SUN1/2 mediate nuclear migration during mammalian retinal development. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1061–1073. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq549. Tissue-specific functionality for the LINC complex based on individual cell type requirements. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111++.Zhang X, Lei K, Yuan X, Wu X, Zhuang Y, Xu T, Xu R, Han M. SUN1/2 and Syne/Nesprin-1/2 complexes connect centrosome to the nucleus during neurogenesis and neuronal migration in mice. Neuron. 2009;64:173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.018. Tissue-specific functionality for the LINC complex based on individual cell type requirements. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Morel V, Lepicard S, Rey AN, Parmentier ML, Schaeffer L. Drosophila Nesprin-1 controls glutamate receptor density at neuromuscular junctions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:3363–3379. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1566-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Coffinier C, Fong LG, Young SG. LINCing lamin B2 to neuronal migration: growing evidence for cell-specific roles of B-type lamins. Nucleus. 2010;1:407–411. doi: 10.4161/nucl.1.5.12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114++.Harada T, Swift J, Irianto J, Shin JW, Spinler KR, Athirasala A, Diegmiller R, Dingal PC, Ivanovska IL, Discher DE. Nuclear lamin stiffness is a barrier to 3D migration, but softness can limit survival. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:669–682. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308029. Tissue-specific functionality for the nucleoskeleton complex based on individual cell type requirements and importance for survival. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115++.Verstraeten VL, Renes J, Ramaekers FC, Kamps M, Kuijpers HJ, Verheyen F, Wabitsch M, Steijlen PM, van Steensel MA, Broers JL. Reorganization of the nuclear lamina and cytoskeleton in adipogenesis. Histochem Cell Biol. 2011;135:251–261. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0792-4. Detailed characterization of functional changes at the NE during development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Melcon G, Kozlov S, Cutler DA, Sullivan T, Hernandez L, Zhao P, Mitchell S, Nader G, Bakay M, Rottman JN, et al. Loss of emerin at the nuclear envelope disrupts the Rb1/E2F and MyoD pathways during muscle regeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:637–651. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bakay M, Wang Z, Melcon G, Schiltz L, Xuan J, Zhao P, Sartorelli V, Seo J, Pegoraro E, Angelini C, et al. Nuclear envelope dystrophies show a transcriptional fingerprint suggesting disruption of Rb-MyoD pathways in muscle regeneration. Brain. 2006;129:996–1013. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Markiewicz E, Dechat T, Foisner R, Quinlan R, Hutchison C. Lamin A/C binding protein LAP2alpha is required for nuclear anchorage of retinoblastoma protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4401–4413. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ozaki T, Saijo M, Murakami K, Enomoto H, Taya Y, Sakiyama S. Complex formation between lamin A and the retinoblastoma gene product: identification of the domain on lamin A required for its interaction. Oncogene. 1994;9:2649–2653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120++.Naetar N, Korbei B, Kozlov S, Kerenyi MA, Dorner D, Kral R, Gotic I, Fuchs P, Cohen TV, Bittner R, et al. Loss of nucleoplasmic LAP2alpha-lamin A complexes causes erythroid and epidermal progenitor hyperproliferation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1341–1348. doi: 10.1038/ncb1793. Disruption of a near-universal complex has tissue-specific consequences with significant ramifications for stem cell renewal in NE disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121++.Korfali N, Srsen V, Waterfall M, Batrakou DG, Pekovic V, Hutchison CJ, Schirmer EC. A Flow Cytometry-Based Screen of Nuclear Envelope Transmembrane Proteins Identifies NET4/Tmem53 as Involved in Stress-Dependent Cell Cycle Withdrawal. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018762. This screen identified 8 tissue-specific NETs that alter cell cycle regulation, expanding their known range of functions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122++.Horn HF, Brownstein Z, Lenz DR, Shivatzki S, Dror AA, Dagan-Rosenfeld O, Friedman LM, Roux KJ, Kozlov S, Jeang KT, et al. The LINC complex is essential for hearing. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:740–750. doi: 10.1172/JCI66911. Tissue-specific LINC complex component directly linked to human disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bonne G, Di Barletta MR, Varnous S, Becane HM, Hammouda EH, Merlini L, Muntoni F, Greenberg CR, Gary F, Urtizberea JA, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding lamin A/C cause autosomal dominant Emery- Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1999;21:285–288. doi: 10.1038/6799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Tiffin HR, Jenkins ZA, Gray MJ, Cameron-Christie SR, Eaton J, Aftimos S, Markie D, Robertson SP. Dysregulation of FHL1 spliceforms due to an indel mutation produces an Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy plus phenotype. Neurogenetics. 2013;14:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s10048-013-0359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125+.Chapman MA, Zhang J, Banerjee I, Guo LT, Zhang Z, Shelton GD, Ouyang K, Lieber RL, Chen J. Disruption of both nesprin 1 and desmin results in nuclear anchorage defects and fibrosis in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:5879–5892. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu310. Tissue-specific cytoplasmic intermediate filament interaction with LINC complex component yields tissue-specific defects. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126++.Tulgren ED, Turgeon SM, Opperman KJ, Grill B. The Nesprin family member ANC-1 regulates synapse formation and axon termination by functioning in a pathway with RPM-1 and beta-Catenin. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004481. Tissue-specific functionality for the LINC complex based on specific partner proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Neumann S, Schneider M, Daugherty RL, Gottardi CJ, Eming SA, Beijer A, Noegel AA, Karakesisoglou I. Nesprin-2 interacts with {alpha}-catenin and regulates Wnt signaling at the nuclear envelope. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34932–34938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Johnson RP, Kramer JM. Neural maintenance roles for the matrix receptor dystroglycan and the nuclear anchorage complex in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2012;190:1365–1377. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129++.Shin JY, Mendez-Lopez I, Wang Y, Hays AP, Tanji K, Lefkowitch JH, Schulze PC, Worman HJ, Dauer WT. Lamina-Associated Polypeptide-1 Interacts with the Muscular Dystrophy Protein Emerin and Is Essential for Skeletal Muscle Maintenance. Dev Cell. 2013;26:591–603. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.012. Different NETs acting together to achieve greater tissue functionality. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ramachandran N, Munteanu I, Wang P, Ruggieri A, Rilstone JJ, Israelian N, Naranian T, Paroutis P, Guo R, Ren ZP, et al. VMA21 deficiency prevents vacuolar ATPase assembly and causes autophagic vacuolar myopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:439–457. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cizkova A, Stranecky V, Mayr JA, Tesarova M, Havlickova V, Paul J, Ivanek R, Kuss AW, Hansikova H, Kaplanova V, et al. TMEM70 mutations cause isolated ATP synthase deficiency and neonatal mitochondrial encephalocardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1288–1290. doi: 10.1038/ng.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bespalova IN, Van Camp G, Bom SJ, Brown DJ, Cryns K, DeWan AT, Erson AE, Flothmann K, Kunst HP, Kurnool P, et al. Mutations in the Wolfram syndrome 1 gene (WFS1) are a common cause of low frequency sensorineural hearing loss. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2501–2508. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.22.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Domenech E, Gomez-Zaera M, Nunes V. WFS1 mutations in Spanish patients with diabetes mellitus and deafness. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:421–426. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Strom TM, Hortnagel K, Hofmann S, Gekeler F, Scharfe C, Rabl W, Gerbitz KD, Meitinger T. Diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy and deafness (DIDMOAD) caused by mutations in a novel gene (wolframin) coding for a predicted transmembrane protein. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:2021–2028. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.13.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sawada A, Takihara Y, Kim JY, Matsuda-Hashii Y, Tokimasa S, Fujisaki H, Kubota K, Endo H, Onodera T, Ohta H, et al. A congenital mutation of the novel gene LRRC8 causes agammaglobulinemia in humans. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1707–1713. doi: 10.1172/JCI18937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yamazaki D, Tabara Y, Kita S, Hanada H, Komazaki S, Naitou D, Mishima A, Nishi M, Yamamura H, Yamamoto S, et al. TRIC-A channels in vascular smooth muscle contribute to blood pressure maintenance. Cell Metab. 2011;14:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zhao X, Yamazaki D, Park KH, Komazaki S, Tjondrokoesoemo A, Nishi M, Lin P, Hirata Y, Brotto M, Takeshima H, et al. Ca2+ overload and sarcoplasmic reticulum instability in tric-a null skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37370–37376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.170084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Froese A, Breher SS, Waldeyer C, Schindler RF, Nikolaev VO, Rinne S, Wischmeyer E, Schlueter J, Becher J, Simrick S, et al. Popeye domain containing proteins are essential for stress-mediated modulation of cardiac pacemaking in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1119–1130. doi: 10.1172/JCI59410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139++.Pestov NB, Ahmad N, Korneenko TV, Zhao H, Radkov R, Schaer D, Roy S, Bibert S, Geering K, Modyanov NN. Evolution of Na,K-ATPase beta m-subunit into a coregulator of transcription in placental mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11215–11220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704809104. Clear demonstration that a protein with defined function in other membranes can evolve a completely distinct NE function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Weber K, Plessmann U, Ulrich W. Cytoplasmic intermediate filament proteins of invertebrates are closer to nuclear lamins than are vertebrate intermediate filament proteins; sequence characterization of two muscle proteins of a nematode. EMBO J. 1989;8:3221–3227. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Soderqvist H, Imreh G, Kihlmark M, Linnman C, Ringertz N, Hallberg E. Intracellular distribution of an integral nuclear pore membrane protein fused to green fluorescent protein–localization of a targeting domain. Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:808–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gerace L, Ottaviano Y, Kondor-Koch C. Identification of a major polypeptide of the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:826–837. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Worman HJ, Yuan J, Blobel G, Georgatos SD. A lamin B receptor in the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8531–8534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Senior A, Gerace L. Integral membrane proteins specific to the inner nuclear membrane and associated with the nuclear lamina. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2029–2036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Foisner R, Gerace L. Integral membrane proteins of the nuclear envelope interact with lamins and chromosomes, and binding is modulated by mitotic phosphorylation. Cell. 1993;73:1267–1279. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90355-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]