Graphical abstract

Keywords: HCG, GnRH agonist, GnRH antagonist, OHSS

Abstract

Final oocyte maturation in GnRH antagonist co-treated IVF/ICSI cycles can be triggered with HCG or a GnRH agonist. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the final oocyte maturation trigger in GnRH antagonist co-treated cycles. Outcome measures were ongoing pregnancy rate (OPR) and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) incidence. Searches: were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, and databases of abstracts. There was a statistically significant difference against the GnRH agonist for OPR in fresh autologous cycles (n = 1024) with an odd ratio (OR) of 0.69 (95% CI: 0.52–0.93). In oocyte-donor cycles (n = 342) there was no evidence of a difference (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.59–1.40). There was a statistically significant difference in favour of GnRH agonist regarding the incidence of OHSS in fresh autologous cycles (OR: 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01–0.33) and donor cycles respectively (OR: 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01–0.27). In conclusion GnRH agonist trigger for final oocyte maturation trigger in GnRH antagonist cycles is safer but less efficient than HCG.

Introduction

In the last decade, GnRH antagonist has been introduced to the market to be used for pituitary desensitization in IVF/ICSI treatment cycles. GnRH antagonist shown to be an effective alternative to the standard long GnRH agonist protocols [1]. There is an ongoing debate over the optimal agent that can trigger final oocyte maturation in GnRH antagonist, leading to higher IVF success rate without increasing the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS).

Due to the specific mode of action of GnRH antagonist, quick and reversible response, GnRH agonist as a mid-cycle bolus dose varying from 0.1 up to 0.5 and HCG administration could be used to induce final oocyte maturation triggering. GnRH agonist induces endogenous LH and FSH surges which might simulate the natural mid-cycle LH surge. The serum LH and FSH levels rise after 4 and 12 h, respectively, and are elevated for 24–36 h. The amplitude of the surges is similar to those seen in the normal menstrual cycle but, in contrast to the natural cycle, the LH surge consists of two phases. These are a short ascending limb (>4 h) and a long descending limb (>20 h). Thus, final oocyte maturation trigger with GnRH agonist results in corpus luteum deficiency and a defective luteal phase (Segal and Casper, 1992) and is associated with very low ongoing pregnancy rate [2]. For this reason, several schemes of luteal support have been used to increase the chance of pregnancy [3–5], although there is no agreement yet regarding which is the optimal one.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), in addition to its well-known endocrine effect on the corpus luteum, it is the traditional final oocyte maturation trigger in GnRH agonist co-treated cycles for more than 3 decades [1]. Some studies have suggested a negative impact of HCG on endometrial [6–8] and embryo quality [9,10]. In addition, the sustained luteotrophic effect of HCG is associated with increased chances of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) [11]. OHSS in its moderate and severe forms can cause significant morbidity and can be fatal in its critical stage. The incidence of severe OHSS is low and in the range of 0.5–2% of all IVF cycles [12].

Currently, there is no agreement on the optimal agent for inducing final oocyte maturation triggering in GnRH antagonist co-treated cycles yet. The purpose of our review was to evaluate and determine the efficacy and safety of both triggers in GnRH antagonist co-treated IVF/ICSI cycles.

Methodology

Search strategy for identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Direct, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Web of Science. National Research Register (NRR) a register of ongoing trials and the Medical Research Council’s Clinical Trials Register a search strategy were carried out based on the following terms: GnRH antagonist, final oocyte maturation triggering, HCG, GnRH agonist, AND ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome chorionic “or “OHSS “AND” IVF/ICSI/ART AND “randomized controlled trial(s)” OR “randomized controlled trial(s)”. Furthermore, we examined the reference lists of all known primary studies, review articles, citation lists of relevant publications, abstracts of major scientific meetings (e.g. ESHRE and ASRM) and included studies to identify additional relevant citations. Finally, the review authors sought ongoing and unpublished trials by contacting experts in the field. In addition, references from all identified articles were checked, and a hand search of the abstracts from the annual meetings of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology was performed. If necessary, additional information was sought from the authors. The search was not restricted by language. The searches were conducted independently by M.Y, M.H and M. van W.

Study selection and data extraction

Studies were selected if the target population was infertile couples undergoing GnRH antagonist co-treated – IVF/ICSI treatment cycles. The therapeutic interventions were GnRH agonist or HCG for final oocyte maturation triggering. Studies had to be of randomized design. The primary outcome measure of interest was ongoing pregnancy rate per randomized woman.

Studies were selected in a two-stage process. First, the titles and abstracts from the electronic searches were scrutinized by two reviewers independently (M.Y and H.A) and full manuscripts of all citations that were likely to meet the predefined selection criteria were obtained. Secondly, final inclusion or exclusion decisions were made on examination of the full manuscripts. The selected studies were assessed for methodological quality by using the components of study design that are related to internal validity (Juni et al., 2001). Information on the adequacy of randomization, concealment and blinding was extracted. When needed the reviewers wrote the authors and tried to get hold of extra information and the raw data. From each study, outcome data were extracted in 2 × 2 tables.

Definition of outcome measures

The outcomes we planned to assess in our analysis were ongoing pregnancy rate and OHSS incidence and number of retrieved follicles were calculated based on the number of patients randomized in all studies even if some patients were excluded or dropped out after randomization.

Statistical analysis

Dichotomous outcomes were expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI using a fixed effects model. Continuous outcomes were expressed as a mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

Results

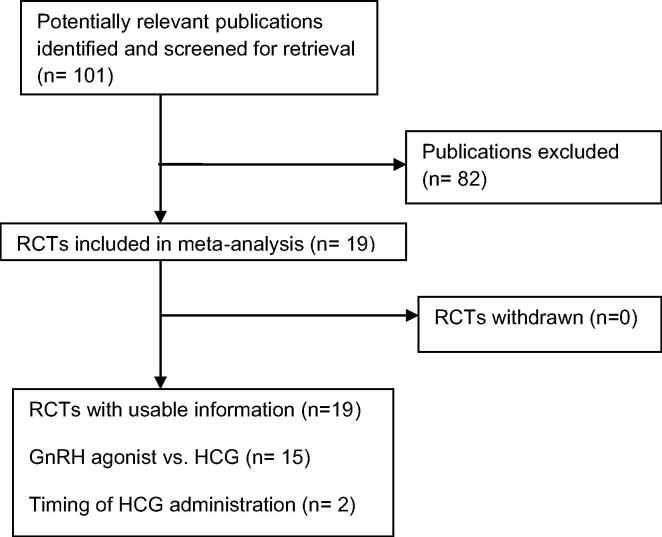

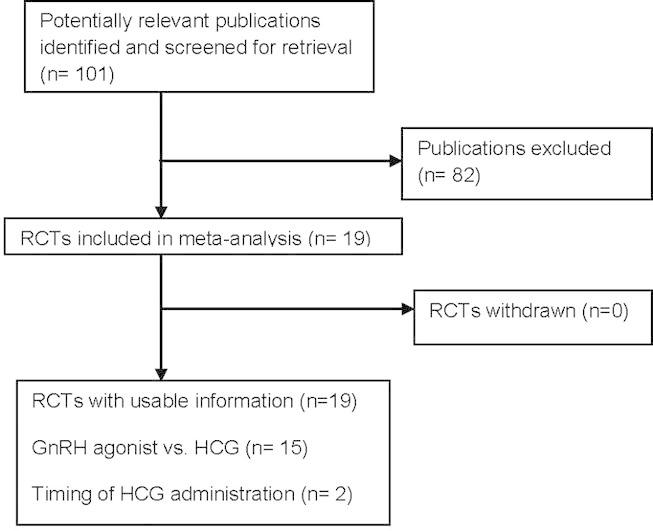

The search strategy yielded 101 publications related to the topic. 82 publications were excluded as they did not fulfil the selection criteria (Fig. 1). Our review and meta-analysis included all randomized controlled studies that evaluated final oocyte maturation triggering in GnRH antagonist co-treated cycles. 15 randomized controlled studies (n = 2259) evaluated GnRH agonist trigger in GnRH antagonist co-treated cycles (Table 1). 15 studies compared HCG with GnRH agonists, 11 RCTs in fresh autologous cycles and 4 RCTs in donor recipient cycles [4,5,13–21,3,22–24]. One study evaluated the lower effective dose of HCG and 3 studies evaluated the effect of delaying or advancement of HCG administration and one study compared u HCG with rec HCG. Nine studies were randomized controlled single-centre studies [3,4,13,14,17,19,22–24]. Four studies were two-centre studies [15,18,20, and 21]. One study was a three-centre study [5] and one study was a six-centre study [16]. Ten studies performed a sample size calculation of the number of patients needed to achieve the primary outcome [4,5,15,18,20,14,17,21,22,24]. There was no sample size calculation in three studies [13,16,3]; in two studies it was unknown [19,23]. Two studies failed to achieve the intended sample size [18,20]. Only three studies performed blinding for the assessors [22–24]. Two studies reported blinding unclearly [15,3]. Other studies reported no blinding. However, blinding of assessors would seem irrelevant given the objectivity of the outcomes. Therefore, all studies were at high risk of bias in regard to blinding. All included studies are published in peer reviewed journals as a full text. Although, there was heterogeneity between the most of the included studies as regards the inclusion and exclusion criteria, primary outcomes and luteal phase support and most of them were properly randomized using computer generated list (see Fig. 2).

-

•

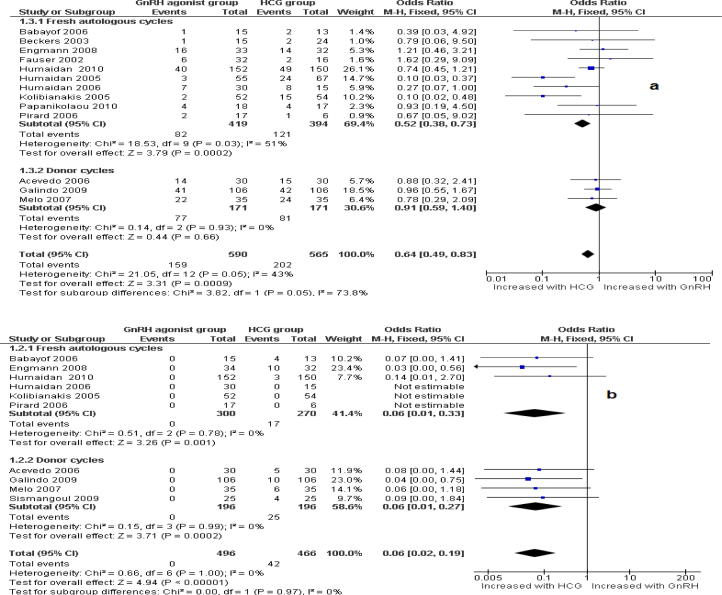

Ongoing pregnancy rate: There was a statistically significant difference against the GnRH agonist with an OPR in fresh autologous cycles (n = 1024) of, OR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.52–0.93. In oocyte-donor cycles (n = 342) there was no evidence of a difference (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.59–1.40).

-

•

Ovarian hyperstimulation incidence (OHSS): There was a statistically significant difference in favour of GnRH agonist regarding the incidence of OHSS in fresh autologous (OR: 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01–0.33 and donor cycles respectively (OR: 0.06; 95% CI: 0.01–0.27).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for meta-analysis. Identification and selection of publications.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomized trials included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

| I-Studies comparing HCG with GnRH agonist in fresh ET-GnRH antagonist co-treated cycles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Study design |

| Randomized controlled studies with traditional luteal phase support | ||||

| 1. Fauser (2002) | 57 women for IVF/ICSI. Age (18–39 years), regular menstrual cycle (24–35 d) and BMI: 18–29 kg/m2 | Ovarian stimulation: adjustable dose of 150–225 IU r FSH + 0.25 mg ganirelix. Intervention: 0.2 mg triptorelin versus 0.5 mg leuprorelin versus 10,000 IU hCG. Luteal phase support: progesterone 50 mg | FSH, LH, E2, hCG, and P in the luteal phase, FSH consumption; duration of FSH treatment, number of oocytes, MII, FR, IR, OPR | RCT, open label, three-arm, 6 international centre study |

| 2. Beckers (2003) | 40 patients for IVF/ICSI. Age ⩽ 38 years, regular menstrual cycle, both ovaries present, absence of uterine abnormalities, BMI: 18–29 kg/m2, no history of poor ovarian response or moderate or severe OHSS | Ovarian stimulation: fixed dose of 150 IU r-hFSH + 1 mg daily sc antide. Intervention: 0.2 mg sc triptorelin versus 250 μg/ml sc r-hCG versus 1 mg sc r-LH. Luteal phase support: none | LH (day of oocyte retrieval), day of progesterone maximal level, day of decrease of P. duration follicular phase, number of oocytes retrieved, OPR | RCT, three arms, two-centre study |

| 3. Kolibianakis (2005) | 106 women for IVF/ICSI. Age ⩽ 39 years, normal day-3 serum FSH levels, ⩽3 previous assisted reproduction treatment (ART) attempts, BMI (18–29 kg/m2), regular menstrual cycles, no PCOS or previous poor response to ovarian stimulation, both ovaries present | Ovarian stimulation: fixed dose of 200 IU r FSH + 0.25 mg orgalutran. Intervention: 0.2 mg triptorelin versus 10 000 IU of HCG. luteal phase support: 600 mg/day natural micronized progesterone plus daily 2 × 2 mg oral estradiol | FR, OPR.IR, days of stimulation, total units of r FSH, number of COCs follicles of ⩾11 mm on the day of triggering, number of follicles of ⩾17 mm, MII% oocytes, number of 2PN oocytes, number of embryos transferred, E2 (pg/ml), progesterone (ng/l) | RCT, two armed, 1:1 randomizations ratio, open label; parallel design; two-centre study |

| 4. Babayof (2006) | 28 women with PCOS for IVF | Ovarian stimulation: adjustable dose of 225 IU sc r FSH + 0.25 mg sc cetrotide. Intervention: 0.2 mg decapeptyl versus 250 μg r HCG. Luteal phase support: 50 mg/day of progesterone Im ± 4 mg/day E2 PO | Serum levels of inhibin A, VEGF, TNFa, E2, progesterone and incidence of OHSS, ovarian size and pelvic fluid accumulation, LBR,OPR, MII% oocytes | RCT, single-centre study |

| Randomized controlled studies with modified luteal phase support | ||||

| (a) GnRH agonist plus low dose of HCG | ||||

| 5. Humaidan (2005) | 122 normo-gonadotrophic women for IVF or ICSI. Age ≈ 25–40 years FSH and LH, 12 IU/l, menstrual cycles between 25 and 34 days, BMI 18–30 kg/m2, both ovaries present, absence of uterine abnormalities | Ovarian stimulation: adjusted dose of 150 or 200 IU r FSH on cd 2 + 0.25 mg ganirelix. Intervention: 0.5 mg buserelin sc versus 10 000 IU hCG sc. Luteal phase support: 90 mg/day P, vaginally + estradiol 4 mg/day | Positive hCG per ET.CPR. Early pregnancy loss, rate of embryo transfer. Numbers of embryos transferred, IR, oocytes retrieved, MII% oocytes | RCT, open label, two-centre study |

| 6. Humaidan (2006) | 45 normo-gonadotrophic women for IVF/IGSI, age 25–40 years, base-line FSH and LH <12 IU/1, menstrual cycles between 25 and 34 days, BMI 18–30 kg/m2, both ovaries present, absence of uterine abnormalities. Each patient contributed with only one cycle | Ovarian stimulation: adjusted dose of 150–200 IU r-hFSH on cd 2+ 0.25 mg ganirelix. Intervention: 0.5 mg buserelin sc plus HGG 1500 IU i.m. 12 h versus 0.5 mg buserelin sc 1500 IU i.m. 35 h after the buserelin injection versus 10,000 IU of HGG sc. Luteal phase support: 90 mg/day P + 4 mg/day estradiol | Serum P, inhibin A concentration, dose of FSH, duration of FSH stimulation, number of oocytes, number of embryos, rate of transfer, number of embryos transferred, CPR, early pregnancy loss | RCT, open label, single-centre study |

| 7. Humaidan (2010) | 302 normo-gonadotrophic IVF/ICSI patients, age 25–40 yrs, BMI 18–30 kg/m2, basal FSH <12 IU/L, menstrual cycle 25–34 days, both ovaries present, absence of uterine abnormalities. Each patient contributed with only one cycle | Ovarian stimulation: adjustable dose of 150–200 IU r FSH + 0.25 mg ganirelix. Intervention: 0.5 mg buserelin sc plus 1500 IU hCG i.m 35 h after triggering of ovulation versus 10 000 IU of hCG. Luteal phase support: 90 mg/day P + E2 4 mg/day | Primary outcomes: reduction of the high early pregnancy loss rate. Secondary outcomes: MII oocytes retrieved, OHSS incidence, ongoing pregnancy rate | RCT, three-centre study |

| 8. Schacter (2008) | 221 infertile patients needing IVF-ET who had failed at least one previous IVF-ET cycle on GnRH agonist long protocol. Exclusion criteria: patients whose previous cycle was characterized by lack of oocytes aspirated. BMI 18–30 kg/m2 | Ovarian stimulation: adjustable dose HMG + 0.25 mg cetrorelix. Intervention: 0.2 mg triptorelin sc plus 1500 IU hCG i.m versus 10,000 IU of hCG. Luteal phase support: vaginal P only (400 mg/d Utrogestan) | OPR, IR | RCT, single centre study |

| Randomized controlled studies with modified luteal phase support | ||||

| (b) GnRH agonist plus intense luteal phase support | ||||

| 9. Pirard (2006) | 30 infertile patients for IVF/ICSI | Ovarian stimulation: OCP + 150–300 IU hMG/FSH on cd 3 + 0.25 mg orgalutran. Intervention and luteal phase support: (group A) 10,000 IU hCG + 200 mg micronized progesterone three times daily, (group B) 200 μg intranasal (IN) buserelin followed by 100 μg IN buserelin/2 days; (group C), 200 μg IN buserelin followed by 100 μg IN buserelin/day, (group D) 200 μg IN buserelin followed by 100 μg IN buserelin twice a day (group E) 200 μg IN buserelin followed by 100 μg IN buserelin three times a day | Luteal phase duration in non-pregnant patients (days), number of patients with a luteal phase >10 days, positive pregnancy test, clinical pregnancy rate, OHSS incidence, retrieved oocytes, retrieved oocytes/follicles >10 mm cleaved embryos, cleaved embryos/retrieved oocytes, transferred embryos | RCT, open, parallel group, pilot, single-centre trial |

| 10. Papinokolaou (2011) | 35 infertile women, inclusion criteria were: [1] age <36 years, [2] elective single embryo transfer on day 5, and [3] basal FSH < 12 mIU/mL. Exclusion criteria were: [1] polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS); [2] use of testicular sperm; and [3] endometriosis stages III and IV | Ovarian stimulation: fixed dose 187.5 IU of rec FSH starting on day 2 of the cycle with co-administration of GnRH-antagonist, 0.25 mg cetrorelix Intervention: 250 mg of recombinant hCG versus 0.2 mg of triptorelin Luteal phase support: 600 mg micronized P vaginally plus six doses every other day of 300 IU recombinant LH (Luveris, Merck-Serono) starting on the day of oocyte retrieval up to day 10 after oocyte retrieval | Implantation rates, clinical pregnancy, OHSS incidence | RCT, single blind study |

| 11. Engmann (2008) | 66 infertile women, age 20–39 years, FSH ⩽ 10.0 IU/L undergoing their first cycle of IVF with either PCOS or PCOM or undergoing a subsequent cycle with a history of high response in a previous IVF cycle | Ovarian stimulation: OCP + long GnRH agonist + r FSH (control group) or 0.25 mg ganirelix. Intervention: 1.0 mg leuprolide versus 3300–10,000 IU of hCG. Luteal phase support: 50 mg IM P + 0.1 mg E2 patches | OHSS, IR, number of oocytes retrieved, MII %, FR, midluteal phase mean ovarian volume (MOV), CPR, OPR | RCT, single centre |

| II-Studies comparing HCG with GnRH agonist in donor-ET-GnRH antagonist co-treated cycles | ||||

| 12. Acevado (2006) | 60 oocyte donors. Age 18–35 years, with normal menstrual cycle: no PCOS, endometriosis, hydrosalpinges, or severe male factor. 98 recipient age range 34–47 years received oocyte but only 60 patients who are analysed | Ovarian stimulation: fixed dose of 150 IU r FSH on cd 3/4 f + 0.25 mg/day sc orgalutran + 75 IU/day of LH. Intervention: 0.2 mg, sc triptorelin versus 250 μg/mL sc r Hcg. Luteal phase support (recipients): E2 plus 600 mg /day natural progesterone | Donors Primary outcomes: OHSS. Secondary outcomes: FSH and LH units(IU), GnRH antagonist ampoules, E2 levels, follicles number on day five of COH and HCG day. Recipients. Pregnancy rates, implantation rates | RCT, single-centre, donor-recipient study |

| 13. Melo (2007) | 70 oocyte donors, age 18–34 years, regular menstrual cycles, no family history of hereditary or chromosomal diseases, normal karyotype, BMI 18–29 kg/m2, and negative screening for sexually transmitted diseases. PCOS was excluded. 96 recipients women with menopause. Exclusion criteria: cases with uterine pathology, implantation failure and recurrent miscarriage | Oocyte donors. Ovarian stimulation: OCP + adjustable dose of 225 IU r FSH + 0.25 mg cetrotide. Intervention: 0.2 mg triptorelin sc versus 250 μg of rhCG sc. Luteal phase support (recipients): 800 mg/day of micronized intravaginal progesterone | Donors: oocytes retrieved, proportion of MII oocytes, fertilization rate, cleavage rate, top quality embryos, N. embryos transferred, OHSS rate. Recipients: implantation rate, clinical pregnancy rate, multiple pregnancy rate, miscarriage rate | RCT, assessor-blinded, parallel groups, single-centre study |

| 15. Galindo (2009) | 257 oocyte donors, age 18–35 years old, BMI < 30 kg/m2 regular (26–35 days) menstrual cycles. Patients with a previous history of low response to ovarian stimulation, PCO or using OCP. were excluded | Ovarian stimulation: 225 IU of r FSH on cd 2 + 0.25 mg/day cetrotide. Intervention: 0.2 mg triptorelin sc versus 250 μg r hCG. Luteal phase support: 800 mg of micronized vaginal progesterone daily | Donors: stimulation duration, FSH dose, final E2 level and follicular count, FR, OHSS incidence. recipients: CPR, LBR, IR | RCT, open label, single-centre study |

| 16. Sismanglou (2009) | Eighty-eight stimulation cycles in 44 egg donors | Ovarian stimulation: r FSH or HMG + GnRH antagonist. Intervention: 0.15 mg leuprolide sc versus 3000–10,000 IU hCG. Luteal phase support: 600 mg of micronized vaginal progesterone daily | MII, oocyte retrieved, implantation and pregnancy rate and OHSS | RCT, cross-over, single centre study |

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of odds rations and 95% CI of pooled trial comparing GnRH agonist versus HCG administration according to the ongoing pregnancy rate (a) and incidence of OHSS per randomized women (b).

Discussion

Our review has shown that HCG administration seems to be more effective trigger for final oocyte maturation in GnRH antagonist co-treated IVF/ICSI treatment cycles than GnRH agonist. This is evidenced by the higher ongoing pregnancy rate we found in the HCG group (15 RCTs, OR: 0.75, 9R% CI: 0.59–0.96). Conversely, GnRH agonists seem to be safer than traditional HCG due to the associated low risk of OHSS (10 RCTs, OR: 0.06, 9R% CI: 0.02–0.19). However, the majority of studies evaluated GnRH agonist was conducted in normo-responder’s patients with normal risk to develop OHSS.

Some investigators suggest that by administrating GnRH agonists rather than HCG, for final oocyte maturation triggering, the risk of OHSS is reduced without compromising pregnancy rates [19–21,3]. Surprisingly, out of 15 studies who evaluated GnRH agonist as a trigger, only 2 small RCTs evaluated agonists in women with PCOS at high risk to develop OHSS, meanwhile other studies included normo-responders women at a normal risk for OHSS. First study shown a nonsignificant reduction in the incidence of OHSS as the number of participants was too small and the primary outcome was inhibin A levels on the day of embryo transfer [14]. Second study, included only 66 infertile PCOS women, the incidence of OHSS was significantly reduced with comparable implantation rates, however, the study was not powered to evaluate pregnancy rate [16]. Marked luteolysis and luteal phase defect have been suggested to be the explanation of the associated lower pregnancy rate. Although, many luteal phase support modifications have been tried, in order to be as efficient trigger as HCG, such as co-administration of low dose of HCG (1500 IU) [25] or multiple doses of GnRH agonist in the luteal phase [24] or multiple injections of rec LH [23] and intense luteal phase support with high doses of progesterone plus estradiol patches [16] to overcome the insufficiency of luteal phase in GnRH agonist group, the pregnancy rate was not improved [2]. Recently, it has been suggested that GnRH agonist trigger with cryopreservation followed by later embryos transfer is more safe and effective [26]. This strategy is supported by the recently published study showing that the clinical pregnancy rate was significantly greater in the cryopreservation group than the fresh transfer group which is attributed to be due to superior endometrial receptivity in the cryopreservation group than the fresh group. These results strongly suggest impaired endometrial receptivity in fresh ET cycles after ovarian stimulation, when compared with FET cycles with artificial endometrial preparation. Impaired endometrial receptivity apparently accounted for most implantation failures in the fresh group [26].

The strengths of this review include comprehensive systematic searching for eligible studies, rigid inclusion criteria for RCTs, and data extraction and analysis by two independent investigators. Furthermore, the possibility of publication bias was minimized by including both published and unpublished studies. However, as with any review, we cannot guarantee that we found all eligible studies.

Conclusions

The evidence suggests that GnRH agonists as a final oocyte maturation trigger in fresh autologous cycles should not be used routinely due to its association with a significantly lower live birth rate, lower ongoing pregnancy rate and higher rate of early miscarriage. The only indication for GnRH agonist use as oocyte maturation trigger is in women who donate oocytes to recipients or in women who wish to freeze their eggs for later use in the context of fertility preservation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Biographies

Mohamed Youssef (1973) obtained his MD’s degree from Cairo University specializing in Obstetrics and Gynecology (2010). He was trained as a clinical and research fellow at the Center for Reproductive medicine at Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. He is studying for his PhD in University of Amsterdam (2010–2014). His research interest includes ‘Managing women with poor ovarian response or high response during IVF/ICSI treatment’. He is currently a lecturer in Obstetrics and Gynecology at Cairo University Hospital, Cairo, Egypt.

Hatem I. Abdelmoty obtained his MD’s degree from Cairo University specializing in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Currently, he is an Assistant Professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology at Cairo University Hospital, Cairo, Egypt.

Mohamed A.S. Ahmed obtained his MD’s degree from Cairo University specializing in Obstetrics and Gynecology. He is working as a Lecturer of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Beni-Suef University.

Maged Elmohamedy obtained his MD’s degree from Cairo University. He is a specialist in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Check J., Nazari A., Barnea E., Weiss W., Vetter B. The efficacy of short-term gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists versus human chorionic gonadotrophin to enable oocyte release in gonadotrophin stimulated cycles. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:568–571. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youssef M.A., Van der Veen F., Al-Inany H.G., Griesinger G., Mochtar M.H., Aboulfoutouh I., Khattab S.M., van Wely M. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist versus HCG for oocyte triggering in antagonist assisted reproductive technology cycles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;19(1):CD008046. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008046.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pirard C., Donnez J., Loumaye E. GnRH agonist as luteal phase support in assisted reproduction technique cycles: results of a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(7):1894–1900. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engmann L., DiLuigi A., Schmidt D., Nulsen J., Maier D., Benadiva C. The use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist to induce oocyte maturation after co-treatment with GnRH antagonist in high-risk patients unde going in vitro fertilization prevents the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a prospective randomized controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humaidan P., Bredkjær H.E., Westergaard L., Andersen C.Y. 1500 IU hCG secures a normal clinical pregnancy outcome in IVF/ICSI GnRH antagonist cycles in which ovulation was triggered with a GnRH agonist. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):847–854. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon C., Cano F., Valbuena D., Remohi J., Pellicer A. Clinical evidence for a detrimental effect on uterine receptivity of high serum estradiol concentrations in high and normal responders. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2432–2437. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forman R., Fries N., Tastart J., Belaisch J., Hazout A., Frydman R. Evidence of an adverse effect of elevated serum estradiol concentrations on embryo implantation. Fertil Steril. 1998;49:118–122. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59661-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon C., Garcia Velasco J.J., Valbuena D., Peinado J.A., Moreno C., Rehmohi J. Increasing uterine receptivity by decreasing estradiol levels during the preimplantation period in high responders with the use of a follicle-stimulating hormone step-down regimen. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:234–239. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valbuena D., Martin J., de Palbo J.L., Remohi J., Pellicer A., Simon C. Increasing levels of estradiol are deleterious to embryonic implantation because they directly affect the embryo. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:962–968. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavaniotou A., Albano C., Smitz J., Devroey P. Impact of ovarian stimulation on corpus luteum function and embryonic implantation. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;55:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(01)00134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerrillo M, Pacheco A, Rodríguez S, Mayoral M, Ruiz M, García Velasco JA. Differential regulation of VEGF, Cadherin, and Angiopietin 2 by trigger oocyte maturation with GnRHa vs hCG in donors: try to explain the lower OHSS incidence. In: Abstracts of the 25th annual meeting of the ESHRE, Amsterdam, June 28–1 July; 2009, vol. 24, 1, p. i60.

- 12.Delvigne A., Rozenberg S. Epidemiology and prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS): a review. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8(6):559–577. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.6.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acevedo B., Jose Gomez-Palomares L., Ricciarelli E., Hernández E.R. Triggering ovulation with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists does not compromise embryo implantation rates. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(6):1682–1687. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babayof R., Margalioth J.E., Huleihel M., Amash A., Zylber-Haran E., Gal M. Serum inhibin A VEGF and TNFa levels after triggering oocyte maturation with GnRH agonist compared with HCG in women with polycystic ovaries undergoing IVF treatment: a prospective randomized trial. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(5):1260–1265. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckers N.G., Macklon N.S., Eijkemans M.J., Ludwig M., Felberbaum R.E., Diedrich K. Non supplemented luteal phase characteristics after the administration of recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin, recombinant luteinizing hormone, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist to induce final oocyte maturation in in vitro fertilization patients after ovarian stimulation with recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone and GnRH antagonist cotreatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(9):4186–4192. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fauser B.C., De Jong D., Olivennes F., Warmsby H., Tay C.J., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Van Hooren H.G. Endocrine profiles after triggering of final oocyte maturation with GnRH agonist after cotreatment with the GnRH antagonist ganirelix during ovarian hyperstimulation for in vitro fertilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):709–715. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galindo A., Bodri D., Guillén J.J., Colodrón M., Vernaeve V., Coll O. Triggering with HCG or GnRH agonist in GnRH antagonist treated oocyte donation cycles: a randomised clinical trial. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:60–66. doi: 10.1080/09513590802404013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humaidan P., Bredkjær H.E., Bungum L., Bungum M., Grøndahl M.L., Westergaard L., Andersen C.Y. GnRH agonist (buserelin) or hCG for ovulation induction in GnRH antagonist IVF/ICSI cycles: a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(5):1213–1220. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humaidan P., Bungum M., Andersen C.Y. Rescue of corpus luteum function with periovulatoryHCG supplementation in IVF/ICSIGnRH antagonist cycles in which ovulation was triggered with a GnRH agonist: a pilot study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;13(2):173–178. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolibianakis E.M., Schultze-Mosgau A., Schroer A., Van Steirteghem A., Devroey P., Diedrich K., Griesinger G. A lower ongoing pregnancy rate can be expected when GnRH agonist is used for triggering final oocyte maturation instead of HCG in patients undergoing IVF with GnRH antagonists. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(10):2887–2892. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papanikolaou E.G., Verpoest W., Fatemi H., Tarlatzis B., Devroey P., Tournaye H. A novel method of luteal supplementation with recombinant luteinizing hormone when a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist is used instead of human chorionic gonadotropin for ovulation triggering: a randomized prospective proof of concept study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(3):1174–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schachter M., Friedler S., Ron-El R., Zimmerman A.L., Strassburger D., Bern O. Can pregnancy rate be improved in gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist cycles by administering GnRH agonist before oocyte retrieval? A prospective, randomized study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(4):1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sismanoglu A1, Tekin H.I., Erden H.F., Ciray N.H., Ulug U., Bahceci M. Ovulation triggering with GnRH agonist vs. hCG in the same egg donor population undergoing donor oocyte cycles with GnRH antagonist: a prospective randomized cross-over trial. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26(5):251–256. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9326-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melo M1, Busso C.E., Bellver J., Alama P., Garrido N., Meseguer M., Pellicer A., Remohí J. GnRH agonist versus recombinant HCG in an oocyte donation programme: a randomized, prospective, controlled, assessor-blind study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19(4):486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griesinger G., Berndt H., Schultz L., Depenbusch M., Schultze-Mosgau A. Cumulative live birth rates after GnRH-agonist triggering of final oocyte maturation in patients at risk of OHSS: a prospective, clinical cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;149(2):190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griesinger G., von Otte S., Schroer A., Ludwig A.K., Diedrich K., Al-Hasani S., Schultze-Mosgau A. Elective cryopreservation of all pronuclear oocytes after GnRH agonist triggering of final oocyte maturation in patients at risk of developing OHSS: a prospective, observational proof-of-concept study. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1348–1352. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]