Abstract

Technologies have become a major force in people’s lives. They change how people interact with the environment, even as the environment changes. We propose that technology use in the setting of changing environments is motivated by essential needs and tensions experienced by the individual. We apply three developmental and behavioral theories (Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model) to explain technology-related behaviors among older adults. We consider how technology use has addressed and can address major ecological changes, in three areas: health promotion, natural disasters, and disparities. We propose that considering these theories can help researchers and developers ensure that technologies will help promote a healthier world for older adults.

Keywords: aging, ecological model, disparities, health promotion, natural disasters, health information technology

Introduction

Observing people today one notices that much of the time is spent using technologies, especially mobile phones, tablets, and portable computers. These mobile information technologies have, over the last several decades, assumed an increasingly larger role in the lives of most of the world’s inhabitants. There are now nearly as many cell phone subscriptions as people in the world, and more people around the world have access to cell phones than working toilets (United Nations, 2013). Unlike prior technologies like the telephone or typewriter which were limited in functionality and required the user to come to them, mobile technologies have become part of the individual’s environment and can perform numerous functions. The user’s local world is modified in the act of contacting other people (via voice or text), finding information (via the Internet), or participating in simulated worlds (via games or media). A mobile technology thus produces its own microenvironment.

The environment constantly is changing. People aging in today’s world have experienced, and can expect to experience, shifts in climate, economic and social relationships, transportation, and built environments. In this article, we endeavor to advance the theoretical understanding of the role technology has in our changing world, with a focus on aging. Our key premise is that technology use in the setting of changing environments is motivated by essential needs and tensions experienced by the individual.

We will explicate three theories of human behavior and development— Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model—and then discuss how they account for the use of technology in three domains related to worldwide ecological change: health, environmental disasters, and disparities in access to technology. We will argue that recognizing the central role of human needs and tensions can broaden the understanding of technology in the modern world, help developers produce more useful technologies, and assist individuals best adapt to and deliberately improve their ecosystems.

The Utility of Theory

A major challenge we face is to understand and address the needs of elders across the globe across different cultures and laws and within varying and changing environments. Seemingly endless empirical questions might arise about how specific groups of people use technologies to address specific needs. One way to address this challenge is to apply theoretical frameworks as a tool to understand general behaviors and motivations. A theory is “a set of interrelated concepts, definitions, and propositions that present a systematic view of events or situations by specifying relations among variables, in order to explain and predict events or situations” (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008, p. 26). Theories have been developed and used to guide human motivation and development research, as well as technology use. The scopes of theories may differ—some focus on individual motivation or development, while others examine the individual within a larger societal context. Even with differing scopes, theories may be complementary. In the following section, we present three theories of behavior and development that have different foci and explain how these theories, both individually and in concert, account for older adults’ use of technology. Finally, we provide three case studies to discuss how these theories can be complementary.

Theories of Human Motivation and Development

Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

Erik Erikson, a developmental psychologist, proposed a theory of individual psychosocial development (Erikson, 1950). He posited that individuals go through eight stages of psychosocial development, defined by competing personality tendencies (i.e., conflicting tension between a positive and negative tendency) and basic virtues (Table 1). The stages occur at different times in people’s lives and are influenced by sociocultural forces. According to Erikson’s theory, elders are in a stage of ego integrity versus despair. Ego integrity involves evaluating and accepting one’s life without regrets, whereas despair arises when elders struggle to feel that their lives were cohesive and meaningful. The virtue of wisdom allows elders to address these competing tendencies. Erikson believed that while elders face physical decline, they must remain socially active, cognitively stimulated, and challenged to ensure psychosocial wellness. Erikson’s last stage of development has different hallmarks or virtues as compared with the other stages. For example, he theorized that young adults are in a stage of intimacy (making deep personal commitments) versus isolation (becoming self-absorbed) when they develop their ethics and sense of self and love.

Table 1.

Health-Related Theories and Major Constructs.

| Theory | Major constructs of the theory |

|---|---|

| Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development | Individuals go through eight stages defined by competing personality tendencies—a tension between a positive and negative tendency. The eight developmental stages (virtue; age range for stage):

|

| Maslow’s hierarchy of needs | Individuals have five levels of needs in which higher level needs are not addressed until lower level needs are met. The five level of needs are:

|

| Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model | Defining property: proximal processes determine behaviors, life decisions, and wellness. Contexts of development:

|

Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development have relevance for technologies aimed at supporting elders who seek integrity. As we will see, the stages can guide research and product development. For example, technologies might support social engagement and connections, which could facilitate elders’ ego integrity and abilities to adapt to changing environments. While researchers have used Erikson’s theory to understand technology use and needs in early life, they have not used it to understand the needs and uses of technology in elders. Gorrindo, Fishel, and Beresin (2012) provide examples of how individuals early in life (from infancy to young adulthood) may use and interact with technology differently depending on their psychosocial developmental stage. For example, Erikson posited that children 3 to 6 years old are in the stage of initiative versus guilt, and that during this time, they grow and develop through play (Erikson, 1950). Therefore, technology use by children 3 to 6 years would likely revolve around play. In contrast, adolescents are in the stage of identity versus role confusion in which they examine who they are and how they relate to others. Therefore, technology use by adolescents would likely revolve around connecting to others.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Despite the complexity of human behavior, some straightforward generalizations apply, which can elucidate why individuals would engage in or avoid certain behaviors. The American psychologist Abraham Maslow framed behavior as working to satisfy various levels of need (Maslow, 1970). People try to accomplish a wide number of goals, which may at times seem idiosyncratic, but they can almost all be understood in a continuum. Maslow identified five levels of needs: physiologic needs, safety needs, love and belonging needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization. Table 1 describes the components of these levels.

In Maslow’s model, higher level needs are not addressed until lower level needs are met. For instance, an individual who is deprived of food or water would concentrate on meeting those basic needs, rather than on developing friendships or creating a masterpiece. Needs are mainly determined by environmental contexts, especially at Maslow’s lower levels of needs. Abundance or shortage of resources, the presence of threats, and the opportunity to sustain social connections influence how or whether individuals are able to satisfy and advance through the hierarchy of need. An unsafe environment, by its nature, would restrict the capacity of its inhabitants to pursue social connectedness, esteem, or self-actualization.

The hierarchy of needs can in a rudimentary way untangle people’s behaviors in a changing world. Basic resources are a key driver, and people are expected to exert much of their effort to their acquisition. Once secured, individuals turn efforts to ensuring a safe environment. Safety can take various forms, but can be described as “defending what one has,” including property, traditions, and morals. The rapid pace of social and technological change in many parts of the world would be expected to force people to focus more on these needs than in times when less change was expected. Because of new technologies, connectedness and belonging needs can be met in far more ways now than in the past, while at the same time the uncertainty of some forms of technology (such as social media) might make it hard to satisfy the need for love and belonging. Regardless of more security regarding physiologic or safety needs, changing social environments can destabilize social needs.

Maslow’s hierarchy as an explanatory model has not been rigorously tested (Reid-Cunningham, 2008). Its strength lies in focusing on the motivational aspects of behavior and establishing a straightforward paradigm to explain why individuals undertake certain actions. Maslow’s framework has been used to explain the adoption of health-related technologies by older adults (Thielke et al., 2012) but has not been applied generally to technology use in different social contexts. We will propose thatMaslow’s hierarchy is a good fit with respect to individual behavior’s using technology and can be used to develop more effective approaches to promote health promotion and disaster preparation.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model for Human Development

Ecological models explain how human development and behavior are influenced by a set of interactions between system structures, such as family, cultural, socioeconomic, political, and psychological domains, which ultimately shape our behavior, life decisions, and wellness over a lifetime. Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological or bioecological model of human development, formulated in 1979, connected disparate fields of research to explain how human beings and the interplay of their environments contribute to human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Lang, 2005). Bronfenbrenner’s model asserts that human development is an evolving complex reciprocal interaction frequently occurring over time between individuals, objects, and symbols in their environments. These environmental interactions are referred to as proximal processes, which are found or take place when one learns new skills or performs difficult tasks. Proximal processes aim to explain how individual characteristics and the immediate and distal environments in which the processes are unfolding result in desired or undesired developmental outcomes. For example, access and use of technology for health purposes depend on the environmental context, such as WiFi capabilities, and education or socioeconomic factors, but can be further influenced by age and level of computer self-efficacy (Hall, Bernhardt, Dodd, & Vollrath, 2014).

The basis of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model resides in levels of environmental influences that puts the individual at the innermost nested level and expands outward toward larger social systems of influence. The first level of influence involves microsystems. Microsystems include interpersonal interactions among family members, friends, teachers, and colleagues. The second level of influence, mesosystems, comprises the relationships and processes that take place between two or more microsystems such as interactions between home and work (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). The next level of influence, exosystems, is the larger social system that comprises two or more settings, including direct and indirect components (e.g., politics, economics, and culture). The final level, macrosystems, consists of overarching cultural and subcultural characteristics that influence all other levels, such as belief systems, knowledge, resources, and lifestyle factors. Another dimension of influence recognized by Bronfenbrenner is chronosystems. Chronosystems extend individual and environment factors to account for the passage of time in which an individual resides and changes or consistencies that occur over the life course, for example employment and family structure changes. Table 1 provides a summary of the model’s constructs.

Bronfenbrenner’s model is well-suited to research information technology use and dissemination in an aging society. Understanding individual and environmental level factors, influences, limitations, and structures can guide developers in designing applications that meet specific user needs. For example, as landline phones continue to be replaced with mobile devices, and health and wellness applications continue to be built only for electronic devices (chronosystems), there is a need to design applications to account for age-related cognitive and physical declines (individual level), changes in relationships, communication needs, and social influences as one ages (microsystems and mesosystems), and access to affordable technology and technology support (exosystems and macrosystems).

Case Studies

We have suggested some ways that behavioral and developmental theories can explain certain observations about technology adoption. We will examine three case studies in detail: health, natural disasters, and disparities in access to technology and consider the relevance of the theories for technology use by older adults, discussing both how they account for technology use, and how they might be applied to develop more useful technologies. We will then synthesize the findings and make recommendations about the future of technologies for aging adults in a changing world.

Case Study 1: Healthy Behaviors

Major advances have occurred over the last century in health care. Ironically, during the same time, measures of health have declined, particularly those stemming from unhealthy behaviors. For example, the prevalence of obesity has increased in every category including age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status in the United States since the mid-20th century as well as in each country where information is available (McAllister et al., 2009). Although the causes are not clear, a variety of environmental factors have been considered central to the “obesity epidemic,” including changes in the built environment (such as less physical work or walking), decreased variability in ambient temperatures (with climate-controlled living), changes in food supply and marketing, and chemical or infectious exposures. Unhealthy eating and inactivity are other unhealthy behaviors that have shown little change over time.

These health trends have drawn the attention of clinicians, government agencies, and industry, and numerous interventions have been developed to promote healthy behaviors such as weight loss, exercise, and smoking cessation. Most of these involve traditional approaches to increasing knowledge and motivation, but many are based on interactive technologies. For instance, dozens of applications track exercise and weight, provide reminders about health activities, and create a social network of individuals who share an interest in adopting healthy behaviors. Monitoring devices that quantify and give feedback about physical activity and sleep are broadly available as consumer electronics and applications.

Despite the broad availability of health promoting technologies, their uptake has been very low, even in carefully conducted research (van Gemert-Pijnen et al., 2011). In a controlled trial of a “toolbox” of health technologies (activity monitoring devices, mobile applications, and Internet services), researchers found that less than a third of the participants continued using the technology resource after a year (Mattila et al., 2013). There is little evidence that health-promoting technologies have produced any significant changes in population health. While technologies for health promotion appear to be broadly available and have enormous potential to modify the relationship between individuals and their environments, they have not had much success. The lack of adoption is not evident.

We will examine this discrepancy between the promise and the use of technologies in promoting health-related behaviors, by considering broadly what health means across different environments, and how technologies do and can influence health-related behaviors. We address four questions in light of Maslow’s and Erikson’s theories: (a) What is health? (b) How is health related to environmental contexts? (c) What needs do health-promotion technologies address? (d) How might technologies better address relevant needs in specific environmental contexts?

(a) What is health?

While health may seem an intuitively obvious construct, its definition has been a challenge through human history. It is not merely the absence of disease, the presence of certain physiological parameters, functional capacity, or a purely physical or mental state, but it is a combination and balance of various domains. Health has different meanings for different people or for the same person at different times. Instead of trying to apply a single definition for health, we will investigate what types of human needs and tensions are addressed by health-promoting behaviors. For example, when someone decides to eat a healthy meal instead of an unhealthy one, or to quit smoking, or to exercise, toward what end do those actions aim?

In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, health does not have any single fixed position but may relate to all the levels (Thielke et al., 2012). Table 1 provides the levels in Maslow’s theory. Health might be considered a requirement for meeting physiological needs, as through the ability to sleep or eat. Maintaining health would thus be considered essential for any activity, or health might be considered a safety need, involving the security of the body. From this perspective, security is not possible without health. While health might not seem directly related to love and belonging needs, participation in social and intimate activities depends largely on physical and mental capacity, making health an apparent core element for love and belonging. Many activities are considered healthy, such as exercise or eating well, but are not essential for meeting physiological needs, safety, or belonging but are pursued because the individual considers them important for her or his esteem. For instance, training for and competing in an athletic event are health-related activities that foster confidence, achievement, and respect. While health and self-actualization may not intuitively overlap, some might propose that mental health is a requirement for being self-actualized, or that some health-related activities such as yoga, tai chi, or meditation are steps that can meet that need.

Maslow’s hierarchy suggests that individuals pursue needs sequentially and that higher level needs are addressed only after lower level needs are met. Different facets of health would therefore apply in different conditions and environments. Someone concerned about finding food and shelter, or about security, would not be expected to focus on healthy eating or exercise as ways of developing esteem. The hierarchy suggests that many aspects of health will not apply to many individuals, if there is a mismatch between the salient need and the health-related activity. Therefore, many health promotion technologies, even if effective at promoting one aspect of health, may fail to help individuals achieve their needs.

Similarly, behaviors that are considered unhealthy, such as smoking and unhealthy eating, do not interfere with most of the levels of need. In fact, the presence of abundant (albeit unhealthy) food might be considered a way to satisfy physiologic and security needs, and if consumed in a social setting, might also satisfy belonging needs. Gourmands might find esteem needs met by unhealthy eating. Smokers describe the security involved in the process of smoking and often engage in this with others, giving them a feeling of belonging. The facets of health that these unhealthy behaviors compromise might be considered higher level and longer term, and thus irrelevant to the behaviors.

Assistive technologies and medications illustrate the challenge with defining where health sits in the hierarchy of needs. Assistive devices (especially those for mobility, such as canes and wheelchairs) are not used in the service of health itself, but rather to satisfy other ends, such as completing tasks independently or participating in society. People use assistive technologies as the means to accomplish other aims than health. Medications may seem, at first glance to meet physiologic needs like food or water, but most are not essential to survival. They may provide a sense of security from applying a treatment or prevention but do not themselves make the individual safer. Medications do not typically address love or belonging needs. Instead, most medications used to treat or prevent disease attempt to satisfy a higher level need related to esteem: being able to lead a healthy or functional lifestyle and preventing future problems. In this context, it is not surprising that adherence to medications is overall poor, with about half of people taking their medications as prescribed (Sabaté, 2003). Insofar as medications are tools for promoting health, health promotion does not seem to be a highly relevant need for many people.

Erikson’s formulation of the tensions in adulthood and late life introduces the same problem with health. Although a basic degree of physical and mental capacity is needed to be productive rather than stagnant (the adult conflict), and to achieve a sense of integrity rather than despair (the late life conflict), nevertheless more advanced degrees of health are peripheral to these aims. For example, one might be very productive and unhealthy. The image of the prolific chain-smoking, heavy-drinking author has become less popular recently, but myth or truth challenges the assumption that healthy behaviors are required to be productive. One can progress successfully through life stages without engaging in specific healthy behaviors and without modifying unhealthy behaviors.

(b) How is health related to environmental contexts?

Whatever the meaning for the individual, “health” does not exist separate from the environment in which one lives. Various lines of research have concluded that environmental effects are major determinants of health behaviors and health status (Garin et al., 2014). Inequality in the built environment has been found to account for disparities in obesity rates and levels of physical activity (Gordon-Larsen, Nelson, Page, & Popkin, 2006). Maslow’s theory provides ready examples of this observation: Individuals in unsafe or deprived environments would be expected to focus on lower level needs rather than health promotion. Safe physical and social environments, on the other hand, would permit one to focus on higher level esteem needs, including adopting a healthy lifestyle such as exercise. Similarly, the differences in physical and social environments across the lifespan would, in Erikson’s model, either promote or thwart accomplishment of life goals, and impede healthy behaviors such as civic engagement, and encourage stagnation and inactivity. Different environments could thus encourage widely divergent behaviors related to health.

Scrutiny of the built environment in most industrialized countries indicates that it is in many ways “set up” to encourage unhealthy behaviors. The ubiquity of fast, cheap, high-calorie foods in many environments may promote unhealthy eating and obesity. The ability or requirement to drive encourages lack of physical activity. The absence of public spaces or sidewalks keeps people indoors. Smoking may be different; many states have banned smoking in or close to public spaces. Environmental landscapes are not homogeneous, and there are many built and natural environments that allow or promote healthy activities. In the context of Maslow’s and Erikson’s theories, environmental factors predetermine many of the needs and tensions faced by individuals and may either create more pressing priorities than health or even obstruct healthy behaviors.

(c) What personal needs and environmental factors do health-promotion technologies address?

A survey of health-promotion technologies suggests that most are geared at monitoring and reminding people to act in healthier ways, using a variety of tactics (Becker et al., 2014). Applications around improving exercise or encouraging weight loss track the individual’s level of activity, display results, and provide feedback. Some applications have developed social networks to allow users to compare their results with those of other users or to compete with them. Other applications have provided reminders about taking medications, communicating with providers, or modifying behaviors through cognitive and behavioral approaches. Although such programs are advertized as providing benefit for the individual, they may not be useful for addressing the individual’s current needs. How would weight loss help satisfy physiologic, security, belonging, esteem, or self-actualization needs? How would it help to promote generativity or developing a sense of integrity in one’s life?

Under closer examination, almost all health-promotion technologies target esteem needs: They promote activities that provide a sense of accomplishment (such as reaching a healthier weight or participating in an athletic event). In the process, they might even undermine other needs (such as being part of a social group that engages in unhealthy eating). Similarly, they encourage a form of productivity that is focused on the self, not on larger contributions to society. As such, they are not directly in service of generativity and could even (by taking time away from work or social participation) hinder being productive. They are typically active instead of reflective, and do not help the user reflect on the past or the meaning of life, so they would not be expected to help in the process of developing integrity. The theories examined would suggest that technologies would be adopted by individuals whose lower level needs have been met and who already have a sense of being productive or having led an integrated life.

Likewise, health promotion technologies are typically not tailored to specific environments or focused on improving natural, social, or built environments. Health promotion technologies are almost exclusively “one size fits all,” and assume that users will want and be able to engage in healthy behavior regardless of the world around them. Gross mismatches may arise between the technology’s behavioral recommendations and the actual environment. For example, recommending walking to someone who lived in a neighborhood without sidewalks.

As suggested earlier, uptake of health promotion technologies has been remarkably low. A variety of causes may explain this, including that health technologies are still novel, but a more fundamental problem may be that these technologies fail to address the key needs and tensions of users and fail to account for the environmental factors that contribute to healthy behaviors. In particular, technologies have mainly targeted esteem-related needs, while many potential users are focused on other types of needs. Health promotion technologies have not been geared to helping people navigate basic life development. They have not considered or tried to change unhealthy environments.

(d) How might technologies better promote health in specific environmental contexts?

Suggestions about better technology design follow naturally from Maslow’s and Erikson’s theories. The most salient is that health technology developers should consider the needs, tensions, and environmental factors related to health for each individual. A set of questions might be used to clarify this:

What are the user’s main needs? (Scales exist to establish which level of Maslow’s hierarchy an individual is in Leidy [1994]).

How do health and health promotion relate to the user’s needs?

At what life stage is the user? What are the key tensions at that stage?

What factors in the natural, built, and cultural environment influence the user’s health and the opportunities for health promotion activities? (Are sidewalks present are public spaces safe? What types of neighborhood stores and eating establishments are present?)

The next step is to identify how technologies might more efficiently help the user to resolve the current needs and tensions in a specific environment. Given the differences among individuals in the domains described above, these approaches will need to be tailored, and a single application or interface would be unlikely to meet all types of needs at once. Our discussion of Maslow’s and Erikson’s theories highlighted ways that these needs and tensions can be identified.

Creativity will be needed in the process of helping people satisfy their needs and developmental tensions in various environments. It is possible that the action steps are more relevant at the community level than the individual level. If it became clear that the built environment in certain neighborhoods was not conducive to health, the logical step would be to build more sidewalks and public spaces. It is possible that technologies could be harnessed to identify problem areas and to target public projects. It may also be possible to use technologies to capitalize on existing resources by informing people about public venues or allowing people more effectively to plan community activities. These are not traditional and direct health promotion tactics but might address more relevant needs such as belonging and safety and promote health as an ancillary benefit.

Case Study 2: Natural Disasters

Every year numerous communities are hit by natural disasters—floods, earthquakes, landslides, and other phenomena. These natural disasters can lead to immediate changes in the environment. Elders and other vulnerable populations are particularly vulnerable to such changes. In general, elders are likely to have multiple chronic medical conditions and live with a disability (National Institutes of Health & World Health Organization, 2011), which may limit their abilities to react to disasters before or while they strike (Aldrich & Benson, 2008). Therefore, when a disaster strikes a community, elders may be disproportionately impacted compared with younger adults, and their health may be negatively impacted.

Hurricane Katrina was a Category 5 storm made landfall in Louisiana on August 29, 2005 causing more than 1,800 deaths across five states (Knabb, Rhome, & Brown, 2005). Most deaths occurred in New Orleans and St. Bernard parishes. While those 65 and older represented about 12% of the population in these parishes, researchers estimated that a majority (60%) of those killed by the storm in those areas were older than 65 years (Jonkman,Maaskant, Boyd, & Levitan, 2009). Reasons for these deaths have been attributed to elders’ lack of ability to leave their residences or nursing homes. Elders who survived the storm lacked access to medication because, for example, they did not bring their medications with them as they evacuated or had difficulties getting refills (e.g., pharmacies were not open or did not have their medications available) (Krousel-Wood et al., 2008), which is a common problem among elders facing disasters (Ochi, Hodgson, Landeg, Mayner, & Murray, 2014). Elders also lacked access to assistive technologies that facilitate independent functioning (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). The lack of medications and assistive technologies were major and immediate consequences of the storm. Among elders 65 and older living at the time of the storm around New Orleans, at least (a) 91,000 persons were managing one or more chronic condition, (b) 27,000 individuals were living with a disability, and (c) 24,000 persons relied on special medical devices (Ford et al., 2006; McGuire, Ford, & Okoro, 2007). The inability to acquire medications and assistive technologies impacted their ability to properly manage chronic conditions and limited mobility.

While we cannot always predict when natural disasters will occur, we can predict the likelihood that certain types of disasters may occur in a given community. For example, it is possible that more hurricanes will make landfall on the Gulf Coast, as indicated by historical weather data (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2012). We also know that certain vulnerable populations, including elders, are disproportionately impacted by natural disasters. With such information, communities and elders might be able to prepare for disasters to lessen their impact; however, this requires a clear understanding of human behaviors during such events. We propose that the theories we have considered both explain responses to disasters and help guide better preparation.

The ecological model in disasters

Disaster preparedness, warnings of approaching disasters, and addressing the aftermath of disasters involve a wide range of stakeholders: elders and their families and friends, communities, health services agencies, and government agencies. These involved parties match the different systems in the ecological model: individual, microsystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. People and entities within each system and in different systems are connected. These connections can represent flows of information from local government agencies (exosystem) about how elders (individuals) can evacuate prior to a disaster. The connections can also represent flows of resources between health and government agencies (exosystem and macrosystem) and between these agencies and elders (individuals). During Hurricane Katrina, individuals sought to sustain and rebuild connections at these various levels with different degrees of success. Contemporary technologies were unable to keep individuals, including elders, connected or to provide necessary information about who was lacking services.

Technology might facilitate better information and resource flows across levels. For instance, geographic information systems, global positioning systems, mobile devices, remote environmental and human sensors, and Internet-based tools have been used in disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina (Pate, 2008), to locate and track individuals impacted by the disaster. An example of a collaborative communications system that was developed after the hurricane was the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Portal (Pezzoli et al., 2007). Government agencies, such as the United States Federal Emergency Management Agency (part of the exosystem), and relief organizations, such as the Red Cross (part of the exosystem), use these tracking data systems to gauge the magnitude of the disaster’s impact and determine where to send resources to communities (part of the ecosystem) and elders (individuals). Because elders are more likely to be negatively impacted by natural disasters, these information technologies can be used to identify and assist elders before, during, and after such events.

Hierarchy of needs in disasters

Similarly, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs accounts for the impact that natural disasters would have on people’s behaviors and use of technologies. As described earlier, the environment influences the ability to satisfy needs and thus to move up to higher levels in the needs hierarchy. When the environment changes, needs will change. Natural disasters typically threaten supplies which may be taken for granted, such as water, food, and sanitation, and may create social instability or uncertainty. Disasters thus quickly lower the level of need of everyone affected.

Older adults may be especially at risk in disasters because they may have been dependent on others before the disaster and after it they may be less able to adapt to changing environmental circumstances. For instance, someone with a mobility impairment, or who used a wheelchair, may find it impossible to navigate flooded streets. If the medical infrastructure was threatened, those who needed regular medical care may be unable to meet their physiologic needs.

Maslow’s theory posits that individuals would use technologies to meet relevant needs in difficult circumstances. Most technologies now are geared at higher level needs such as social connectedness, work productivity, entertainment, or finding information and not simply staying alive or safe. Some agencies have developed tools that could help in disasters. For example, the American Red Cross has a smartphone-based “shelter-finding” app (American Red Cross, 2014). Technologies could also assist agencies in getting elders the basics they need. The Panamanian Red Cross has successfully used smartphones to help distribute water to individuals living in areas with contaminated water (Guevara, 2014). During Hurricane Katrina, the American Red Cross used geographical information systems before the storm to plan where to set up shelters and distribute water, food, and other supplies needed to meet basic physiologic needs (Esri, 2005).

Although these tools exist and provide some benefits, they clearly are not sufficient to deal with a wide-scale disaster when thousands of people are unable to meet basic needs. The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina was complicated, and most of the efforts were not facilitated by technologies. Most people affected by the hurricane did not have devices that could be used to locate them or to identify their status or needs. It is possible that technologies could organize the provision of assistance during the critical and potentially long time between when a disaster strikes and when people receive help.

Using theory and technology for improved disaster preparation

More research is needed to understand how technologies could support elders in times of disasters. Researchers interested in addressing elders’ needs from an ecological perspective could investigate how tracking technologies could be integrated into medical communication and information sharing technologies, as elders are more likely to have multiple chronic conditions compared with younger adults. Individuals with chronic illnesses faced many barriers after Hurricane Katrina, including having health and medication information available and getting prescription medications (Arrieta, Foreman, Crook, & Icenogle, 2009). Elders who utilize assistive devices may also benefit from medical communication and information technologies. They may lose devices, or devices may stop functioning during and after a disaster. The Louisiana Assistive Technology Access Network (2013) acknowledges this need and provides individuals, including elders, with disaster preparedness information on their website and assistive technology assistance before, during, and after disasters that can be accessed by calling the network.

Researchers interested in applying Maslow’s model to their research could address the disaster preparedness challenge that individuals are unlikely to attend to needs that they consider already met. Because most Americans are able to access food, water, and shelter and to live in a safe world, most of the time there seems to be little incentive to plan for these needs suddenly when they may cease to be met. Therefore, disasters catch people off guard, even when there is some advance warning. It is possible that technologies could be developed and implemented that would serve as a “backup” in cases of emergencies or natural disasters and would help people to locate safe places, basic supplies, and other people. Smartphones could be designed to have a “disaster mode” in which nonessential features are turned off to conserve battery life, and other features (such as geographical positioning, weather, and public service announcements) are made more prominent. Given the history and practice of emergency of preparedness, it seems unlikely that people would make an ongoing deliberate effort to be ready for dramatically changing circumstances, and technologies may be better able to accomplish that goal.

Case Study 3: Ecological Disparities Related to Access to Technologies

Communities and individuals in developed and developing countries experience disparities and inequalities, related to socioeconomic status, ethnicity, gender, disability, geography, natural resources, access to resources, and politics. According to the World Health Organization (2014), life expectancy can vary as much as 36 years among countries. However, in recent years, overall life expectancy has increased for older adults (≥65 years old), and older adults represent the fastest growing segment of the global population, estimated to account for 16% of the total population by 2050 (Haub, 2013). As people age they are at an increased risk of developing a chronic condition and experiencing age-related declines in hearing, vision, cognition, and mobility. Changes in income, social relationships, political involvement, residence, climate, and personal needs (support from caregivers) further exacerbate ecological disparities due to aging. Advances in technology could potentially foster healthy aging and combat ecological disparities that could be exacerbated in an aging society.

One of the key disparities in the built environment is access to technology. Access to affordable technology has increased in the 21st century. For example, mobile penetration has reached 96%, with approximately seven billion mobile phone subscriptions worldwide and over eight trillion text messages sent (Liu, 2013; Sanou, 2014). A 2013 report from the International Telecommunication Union found that mobile broadband subscriptions (via smartphones, tablets, and laptops) are growing at a rate of 30% per year. However concerns over a “digital divide” (i.e., gap between those who have access to information and communication technologies and those who do not) persists, as many developing countries remain unconnected (Bernhardt, 2000; International Telecommunication Union, 2013). Connection to broadband and the Internet is crucial for social and economic development and to bridge ecological disparity gaps through greater exchanges of educational, environmental, and health information and management services. Further concerns related to the digital divide are lower levels of technology use by older adult cohorts who may be limited by disabilities and lack of experience and access to technology.

How information and communication technologies meet the basic needs of an aging population and have the potential to bridge ecological disparity gaps can be understood through the theories presented. Older adult cohorts may experience physical, mental, and social changes that make them particularly vulnerable to social isolation, civic disengagement, and negative consequences from economic and climate changes. Many older adults prefer to age in place and remain living independently in their homes. Their basic needs and motivation to use technology might thus be described by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs for physiological well-being, safety and to remain connected to loved ones. Erikson’s theory suggests that their needs focus on developing ego integrity versus despair, which may be found through civic engagement and meaningful involvement.

Understanding aging-related motivations for information and communication technology engagement can guide researchers and designers to develop more tailored features and customized devices. For example, smart home and wearable sensor technologies that monitor physical activity, home temperature, weather, home water and power use, medications, and falls might meet the needs for elders’ physiological well-being and safety. The ability to connect with healthcare providers and services remotely through use of telemonitoring or telecare and remain engaged in community and family activities (e.g., Skype), if mobility is limited, are all possible with technology. Nevertheless, such technologies would not likely be applied uniformly for users of different socioeconomic backgrounds, and they could end up exacerbating disparities in technology use.

While Maslow’s and Erikson’s theories address individual levels of need and motivation to use information technologies, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model expands this to address the larger interplay of social influences and systems that either bridge or dam ecological disparity gaps. A top down approach is imperative when addressing the chronosystems, exosystems, and macrosystems levels of technology access and connectivity. Realizing the full economic and social potential of information and communication technologies starts with affordable access to technology and broadband connectivity, which is largely dependent on political and economic forces.

However, mobile phone and device applications are fast becoming ubiquitous around the world, regardless of socioeconomic status (addressing microsystems and mesosystems levels, in addition to the other levels). Mobile phones are being used as banks to exchange money, for texting vital health information (prevention, treatment, public health announcements, such as the “Florence” system in the United Kingdom) and basic communication needs for social and work purposes. Moreover, free mobile texting applications are now available such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, which can meet a communication need at no cost to the consumer. Smartphone developers are now building phones with sensors, such as accelerometers, and other features that can monitor physical activity and changes in mood. There are also many other available mobile applications and devices for the self-management of chronic diseases that meet the health information needs of consumers.

Advances in technology show great promise as solutions to address ecological disparities; however, future research should focus on technology access to and barriers among older adult cohorts. Research should also target motivation for engagement for the users of technology and consider multiple levels of social, political, and economic influences (e.g., technology support from friends or family members, cheaper technologies, political mandates). Designing information technologies for the most vulnerable populations could improve the quality of life for our aging society.

Discussion

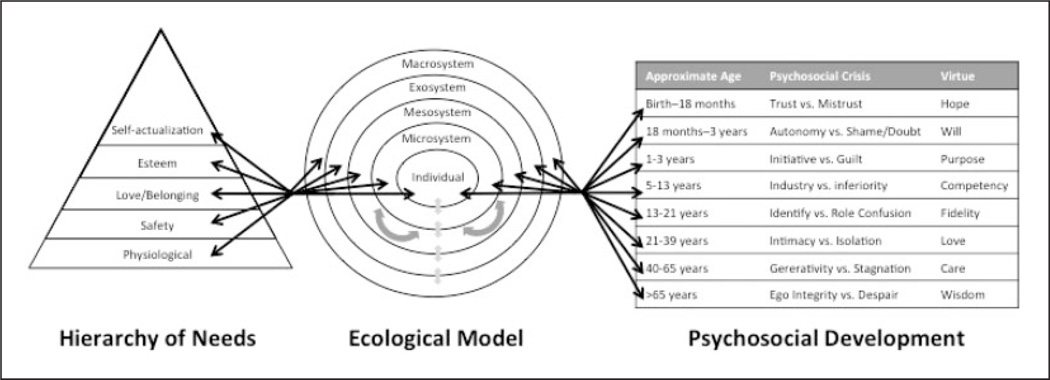

Our examination of three key behavioral and developmental theories—Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological Model—has highlighted ways that older adults do and can use technologies in different circumstances. We suggested that older adults’ use of technology is motivated not by characteristics of the technology or by their idiosyncratic desires but rather by the (a) situation of the elder in a specific environment and (b) needs and tensions that develop out of the elder– environment relationship. Also, we discussed how changes in the natural and built environment have altered these needs and tensions, and how in the future these environments will continue to change. Because of these changes that impact elders and the communities in which they live, it may be useful to consider whether it would be beneficial to use multiple complementary theories that consider different scopes. Figure 1 provides a visualization of how the different constructs in Erikson’s, Maslow’s, and Bronfenbrenner’s theories and model can complement each other. Different parts of the various constructs would address different aspects of technology use and encourage consideration of other models of behavior and motivation.

Figure 1.

How constructs in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model, and Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development can complement each other.

Around the world, mobile technologies have become a core part of human environments. We have pointed out ways that technology has tried to support elders in adapting to and thriving within different and changing environments. For instance, health promotion devices and disaster preparedness applications can encourage older adults to change their behaviors. Most elders’ use of technologies has been to satisfy belonging needs (in Maslow’s hierarchy), help have productive relationships (in Erikson’s stages), or improve functioning in the microsystem and mesosystem (in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model). The most successful technologies, such as cellular phones, texting, social media, and other electronic forms of communication, have helped elders develop connections. It seems possible that despite future environmental changes technologies will still be geared toward social interactions. Therefore, researchers should consider developing or modifying technologies that complement social interactive technologies. We have argued that theoretical models both explain behavior and also offer guidance about future development of these technologies. Some of the key needs and tensions that technologies have not yet addressed might merit additional attention and coincidentally help to build a safer, more stable, nurturing, and just world. Some potential areas include:

Design a “disaster mode” function on electronic devices such as smartphones.

Identify the user’s level of need and gear health promotion applications to that level (rather than assuming that the individual will seek out health as an end in itself).

Develop opportunities for individuals to provide care to others by means of remote technologies.

Attend to the limited connectivity of older adults.

Improve access to electronic information and social initiatives and eliminate the digital divide.

Gather inhabitants’ information about the built environment to plan public projects (such as density and location of sidewalks or parks).

Connect people and communities to tools to systematically monitor environmental changes.

These are but a few suggestions. More generally, we hope that developers and policymakers will reflect on and apply theories of human behavior and be aware of the importance of built and natural environments as they plan and design products and projects.

Conclusion

Theories can be invaluable tools to understand how and if technology can support elders as they adapt to and cope with environmental changes. Maslow’s and Erikson’s theories and Bronfenbrenner’s model can be used to guide research and the development of tools to help elders and communities to plan for and react to changing environments. These tools can be designed to promote health, prepare for and react to natural disasters, and overcome disparities in technological access, all of which may support elders in changing environments.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr. Backonja and Dr. Hall’s work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine (NLM) Biomedical and Health Informatics Training Program at the University of Washington (Grant Nr. T15LM007442). Dr Thielke was supported by NIMH K23 MH093591.

Biographies

Dr. Uba Backonja is a National Library of Medicine Postdoctoral Fellow in biomedical and health informatics at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Her research interests include women’s health promotion, community health nursing, consumer health informatics, health equity, and data visualization.

Dr. Amanda K. Hall is a National Library of Medicine Postdoctoral Fellow in biomedical and health informatics at the University of Washington School of Medicine. She conducts research on the design and evaluation of health information technologies and their effective use to disseminate health information to improve medical decision-making and promote health behavior change among older adults.

Dr. Stephen Thielke is a geriatric psychiatrist and health services researcher at the Seattle VA Medical Center and the University of Washington Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. He conducts research about mental health, technology, medical care, and life changes among older adults.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aldrich N, Benson WF. Disaster preparedness and the chronic disease needs of vulnerable older adults. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2008;5(1):A27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Red Cross. Shelter finder app. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.redcross.org/ mobile-apps/shelter-finder-app. [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta MI, Foreman RD, Crook ED, Icenogle ML. Providing continuity of care for chronic diseases in the aftermath of Katrina: From field experience to policy recommendations. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2009;3(3):174–182. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181b66ae4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Miron-Shatz T, Schumacher N, Krocza J, Diamantidis C, Albrecht UV. mHealth 2.0: Experiences, possibilities, and perspectives. Journal of Medical Internet Research Mhealth Uhealth. 2014;2(2):e24. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt JM. Health education and the digital divide: Building bridges and filling chasms. Health Education Research. 2000;15:527–531. doi: 10.1093/her/15.5.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. International encyclopedia of education. 2nd. ed. Vol. 3. Oxford, England: Elsevier; 1994. Ecological models of human development. (Reprinted from Readings on the development of children, pp. 37–43, by M. Gauvain & M. Cole, Eds.,1993, New York, NY: Freeman). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s disaster planning goal: Protect vulnerable older adults. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/disaster_planning_goal.pdf.

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Esri American Red Cross uses GIS for Hurricane Katrina and Rita Efforts. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.esri.com/news/arcnews/fall05articles/american-redcross. html. [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES, Mokdad AH, Link MW, Garvin WS, McGuire LC, Jiles RB, Balluz LS. Chronic disease in health emergencies: In the eye of the hurricane. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3(2):A46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin N, Olaya B, Miret M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Power M, Bucciarelli P, Haro JM. Built environment and elderly population health: A comprehensive literature review. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2014;10:103–115. doi: 10.2174/1745017901410010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, Popkin BM. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):417–424. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorrindo T, Fishel A, Beresin EV. Understanding technology use throughout development: What Erik Erikson would say about toddler tweets and Facebook friends. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Life Cycle and Family. 2012;10(3):282–292. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara EJ. Panamanian Red Cross uses new technology to streamline distribution of humanitarian aid. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.ifrc.org/en/news-and-media/news-stories/americas/panama/panama-red-cross-uses-new-technology-to-streamlinedistribution-of-humanitarian-aid-66450/ [Google Scholar]

- Hall AK, Bernhardt JM, Dodd V, Vollrath MW. The digital health divide: Evaluating online health information access and use among older adults. Health Education & Behavior. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1090198114547815. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haub C. World population aging: Clocks illustrate growth in population under age 5 and over age 65. 2013 Retrieved from Population Reference Bureau website: http://www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2011/agingpopulationclocks.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union. Broadband goes wireless—But poorer countries being left behind. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.itu.int/net/pressoffice/press_releases/2013/36.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman SN, Maaskant B, Boyd E, Levitan ML. Loss of life caused by the flooding of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: Analysis of the relationship between flood characteristics and mortality. Risk Analysis. 2009;29(5):676–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knabb RD, Rhome JR, Brown DP. Tropical cyclone report, Hurricane Katrina. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL122005_Katrina.pdf.

- Krousel-Wood MA, Islam T, Muntner P, Stanley E, Phillips A, Webber LS, Re RN. Medication adherence in older clinic patients with hypertension after Hurricane Katrina: Implications for clinical practice and disaster management. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2008;336(2):99–104. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318180f14f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang SS. Urie Bronfenbrenner, father of head start program and pre-eminent ‘human ecologist,’ dies at age 88. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/2005/09/head-start-founder-urie-bronfenbrenner-dies-88. [Google Scholar]

- Leidy NK. Operationalizing Maslow’s theory: Development and testing of the basic need satisfaction inventory. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1994;15(3):277–295. doi: 10.3109/01612849409009390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. How many text messages are sent each year? 2013 Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/video/how-many-text-messages-are-sent-each-year-RDvLwi1WRgii6HMmiVk_Fw.html. [Google Scholar]

- Louisiana Assistive Technology Access Network. Louisiana: Be prepared for hurricane season. 2013 Retrieved from https://latan.org/index.php/component/content/article/23-emergency-preparedness/27-emergency-preparedness-program.html. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister EJ, Dhurandhar NV, Keith SW, Aronne LJ, Barger J, Baskin M, Allison DB. Ten putative contributors to the obesity epidemic. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2009;49(10):868–913. doi: 10.1080/10408390903372599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire LC, Ford ES, Okoro CA. Natural disasters and older US adults with disabilities: Implications for evacuation. Disasters. 2007;31(1):49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow A. Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper and Rowe; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mattila E, Orsama AL, Ahtinen A, Hopsu L, Leino T, Korhonen I. Personal health technologies in employee health promotion: Usage activity, usefulness, and health-related outcomes in a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research Mhealth Uhealth. 2013;1(2):e16. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health & World Health Organization. Global health and aging. 2011 (National Institutes of Health publication number11-7737). Retrieved from http://www.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/global_health_and_aging.pdf.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Hurricanes. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/severeweather/hurricanes.html.

- Ochi S, Hodgson S, Landeg O, Mayner L, Murray V. Disaster-driven evacuation and medication loss: A systematic literature review. PLOS Currents Disasters. 2014 doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.fa417630b566a0c7dfdbf945910edd96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate BL. Identifying and tracking disaster victims: State-of-the-art technology review. Family and Community Health. 2008;31(1):23–34. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000304065.40571.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzoli K, Tukey R, Sarabia H, Zaslavsky I, Miranda ML, Suk WA, Ellisman M. The NIEHS environmental health sciences data resource portal: Placing advanced technologies in service to vulnerable communities. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007;115(4):564–571. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid-Cunningham AR. Maslow’s theory of motivation and hierarchy of human needs: A critical analysis. Berkeley: School of Social Welfare, University of California; 2008. (Unpublished thesis). [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sanou B. The world in 2014. ICT facts and figures. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.itu.int/en/ITUD/Statistics/Documents/facts/ICTFactsFigures2014-e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Thielke S, Harniss M, Thompson H, Patel S, Demiris G, Johnson K. Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs and the adoption of health-related technologies for older adults. Ageing International. 2012;37(4):470–488. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Deputy UN chief calls for urgent action to tackle global sanitation crisis. 2013 Mar 21; Retrieved from http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=44452#.VHv4_mTF94. [Google Scholar]

- van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Nijland N, van Limburg M, Ossebaard HC, Kelders SM, Eysenbach G, Seydel ER. A holistic framework to improve the uptake and impact of eHealth technologies. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13(4):e111. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World conference on social determinants of health: Fact file on health inequities. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/sdhconference/background/news/facts/en/ [Google Scholar]