Abstract

The water fern Azolla harbors nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena azollae as symbiont in its dorsal leaves and is known as potent N2 fixer. Present investigation was carried out to study the influence of fresh Azolla when used as basal incorporation in soil and as dual cropped with rice variety Mahsoori separately and together with and without chemical nitrogen fertilizer in pots kept under net house conditions. Results showed that use of Azolla as basal or dual or basal plus dual influenced the rice crop positively where use of fern as basal plus dual was superior and served the nitrogen requirement of rice. There was marked increase in plant height, number of effective tillers, dry mass and nitrogen content of rice plants with the use of Azolla and N-fertilizers alone and other combinations. The use of Azolla also increased organic matter and potassium contents of the soil.

Keywords: Rice, Water fern Azolla, Crop response, Soil enrichment

Introduction

The use of biofertilizers and green manures is not only a need for sustainable agriculture but also an environment friendly and economically feasible scientific method. The integrated use of organic and inorganic fertilizers is desirable to sustain crop yields and maintenance of soil health (Meelu and Singh 1991; Prasanna et al. 2008). Azolla is a free-floating water fern and has agronomic importance due to its ability to fix nitrogen (Singh 1977). It forms a nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with the cyanobacterium Anabaena azollae, which is present in the leaf cavity of the fern (Watanabe 1982, spore 1992). Azolla is grown as a green manure before transplantation of rice or as an intercrop with the rice. Both the practices are reported to increase the growth and yield of rice (Singh 1989; Singh and Singh 1995).

In Asia, Azolla is the most commonly used green manure for rice crop, due to its high growth rate, nitrogen-fixing capacity and ability to scavenge nutrients from soil and water. The fern doubles its biomass in 2–5 days under ideal environmental conditions (Watanabe et al. 1989). Azolla can supply more than half of the required nitrogen to the rice crop and besides providing nitrogen it is beneficial in wetland rice fields for bringing number of changes which include preventing rise in pH, reducing water temperature, curbing NH3 volatilization, suppressing weeds and mosquito proliferation (Pabby et al. 2004).

Therefore, the present study was undertaken to examine the feasibility of using Azolla as nutritional alternative for rice crop. Consequently, the main objective of this work was to study the influence of Azolla as green manure or dual crop on rice crop growth and development.

Materials and methods

Pot incubation experiment was conducted between June and October 2012 under net house condition at the Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University (B.H.U.), Varanasi, India. Soil samples used in this experiment were collected from Khaira, a village near Varanasi, India. All the samples were brought to the laboratory, where sieving was done with 2-mm sieve. Part of the sieved soil was air dried and some chemical properties were determined (Table 1). Five kg of soil was weighed with a balance and kept into each, 48 pots having holes at the base. There were three pots per treatment and the control experiment was inclusive. Six seedlings of Mahsoori rice variety were transplanted in each pot. Azolla was used as green manure (basal) and dual (associated), at the rate of 0.012 kg pot−1 (2 ton ha−1) and in basal treatments it was incorporated in soil before transplanting. Equal shares of A. pinnata and A. filiculoides were mixed for achieving a more stable plant growth. A list of treatments along with the abbreviations used in the text and figure is given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Initial soil properties at the start of the experiment

| Soil parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Organic matter (OM), % | 3.12 |

| Phosphorus (P), ppm | 54.0 |

| Calcium (Ca), kg ha−1 | 17.2 |

| Potassium (K), kg ha−1 | 0.19 |

| Magnesium (Mg), kg/ha−1 | 2.4 |

| pH | 6.6 |

Table 2.

Details of treatments and abbreviations used in the text

| S. no | Treatments | Abbreviations | Treatment no |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Without nitrogen (Control) | 0N | T1 |

| 2 | 30 kg ha−1 nitrogen | 30N | T2 |

| 3 | 60 kg ha−1 nitrogen | 60N | T3 |

| 4 | 90 kg ha−1 nitrogen | 90N | T4 |

| 5 | 0N + Basal Azolla (BA) | 0N + BA | T5 |

| 6 | 30N + Basal Azolla (BA) | 30N + BA | T6 |

| 7 | 60N + Basal Azolla (BA) | 60N + BA | T7 |

| 8 | 90N + Basal Azolla (BA) | 90N + BA | T8 |

| 9 | 0N + BA + Dual Azolla (DA) | 0N + BA + DA | T9 |

| 10 | 30N + BA + Dual Azolla (DA) | 30N + BA + DA | T10 |

| 11 | 60N + BA + Dual Azolla (DA) | 60N + BA + DA | T11 |

| 12 | 90N + BA + Dual Azolla (DA) | 90N + BA + DA | T12 |

| 13 | 0N + Dual Azolla (DA) | 0N + DA | T13 |

| 14 | 30N + Dual Azolla (DA) | 0N + DA | T14 |

| 15 | 60N + Dual Azolla (DA) | 0N + DA | T15 |

| 16 | 90N + Dual Azolla (DA) | 0N + DA | T16 |

Nitrogen applied to each treatment:

- 0N

Control

- 30N

0.18 g N pot−1 (30 kg ha−1)

- 60N

0.36 g N pot−1 (60 kg ha−1)

- 90N

0.54 g N pot−1 (90 kg ha−1)

The following measurements were performed:

Plant height (at 100 % heading).

Number of fertile tillers per plant (at 100 % heading).

Dry mass.

Nitrogen, phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) content.

Soil chemical analysis (organic matter, pH, P, K, Ca and Mg).

Sampling was performed 45 days after incorporating Azolla.

The pH of the soil was determined using pH meter with glass-column combination electrode in distilled water and 0.01 M CaCl2 solution at a ratio of 1:2 soil solution. The organic matter was determined using Walkley and Black method (Jackson 1967). Total nitrogen was determined by Kjeldahl method (Jackson 1973). Exchangeable K, Ca and Mg were extracted using ammonium acetate, K was determined on flame photometer and Ca and Mg by EDTA titration.

Statistical analysis was performed by Tukey HSD test using the SPSS 16.0 (Statistical package for Social Sciences) software package.

Results

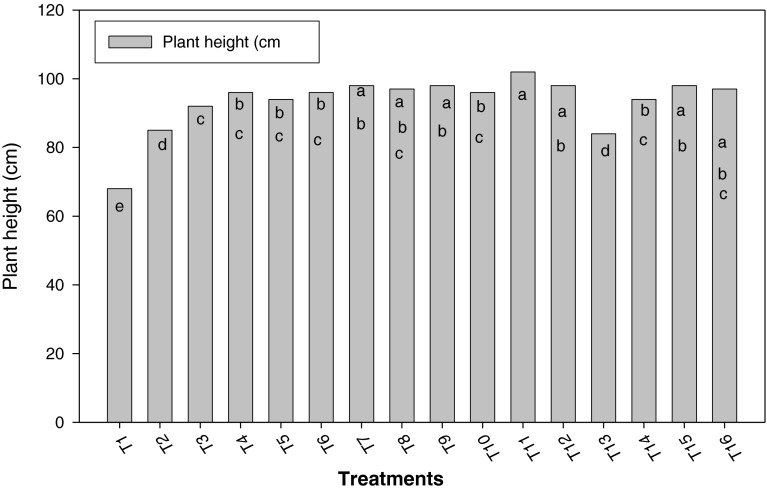

Figure 1 shows the behavior of the rice plant height, influenced by Azolla incorporation and/or association as well as different nitrogen (N) rates. An increase for this character is seen in treatments where incorporated and/or associated Azolla was used. However, nitrogen dose and Azolla influence did not show significant differences, expect for the treatments in which 30 kg ha−1 N doses with T6 incorporated Azolla and 60 kg ha−1 N doses with T11 incorporated and associated Azolla were applied. Treatments from T7 to T12 and T14 to T16, in which incorporated and/or associated Azolla was used, presented the greatest plant height values, without showing significant differences among them. Treatment T9 stood out, in which nitrogen was not applied and both ways of Azolla were performed. It was also observed that treatments where Azolla was used without nitrogen also showed better behavior with significant differences in relation to control, which presented a poor plant growth, just 67.25 cm high.

Fig. 1.

Influence of treatments on rice plant height

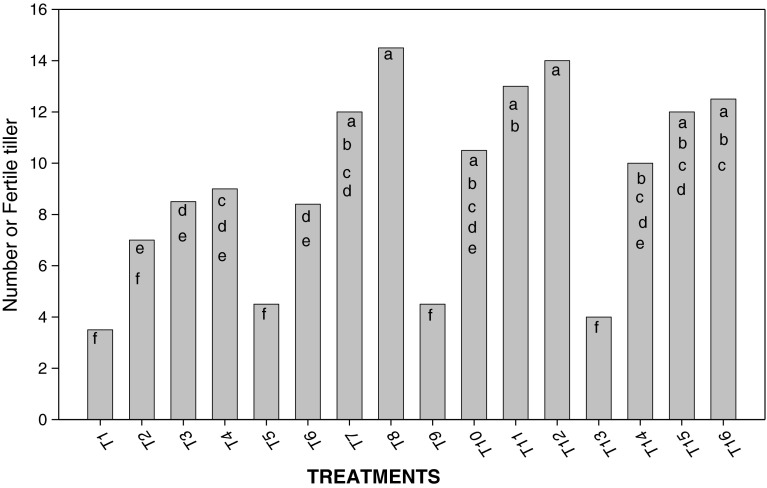

Figure 2 shows the number of effective tillers per plant. Nitrogen doses applied together with Azolla in this experiment influenced this variable as well. Treatments where Azolla was incorporated and/or associated (T8, T12, T11, T16, and T7) stood out, for presenting the highest number of tillers per plant. (All the data are significant p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Influence of treatments on the number of fertile tillers a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i shows the significant differences on the basis of Tukey HSD

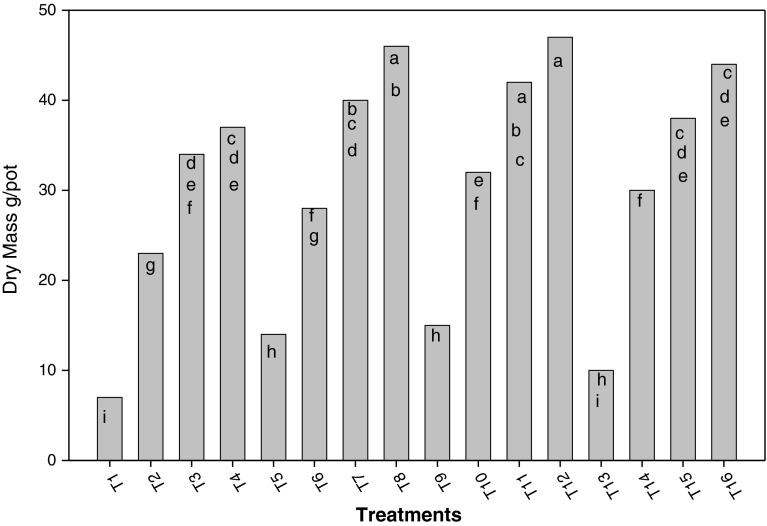

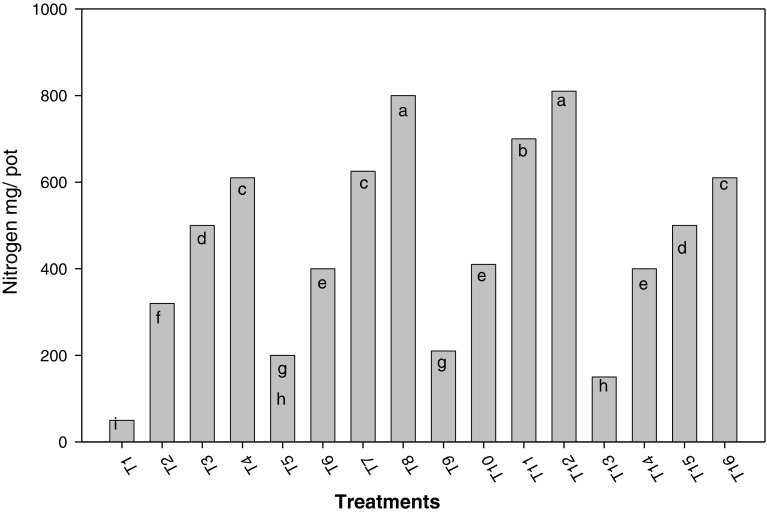

Figures 3 and 4 show nitrogen extracted by rice plants and plant dry mass at different variants, up to 100 % flowering. Like the number of tillers per plant and height, nitrogenous fertilization along with Azolla influenced nitrogen extracted by plants and dry mass production. Treatments T8 and T12 presented the highest nitrogen concentrations in plants. In both of them, incorporated Azolla and incorporated and associated Azolla at 90 kg ha−1 N were used.

Fig. 3.

Influence of treatments on rice dry mass a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i shows the significant differences on the basis of Tukey HSD

Fig. 4.

Influence of treatments on nitrogen content a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i shows the significant differences on the basis of Tukey HSD

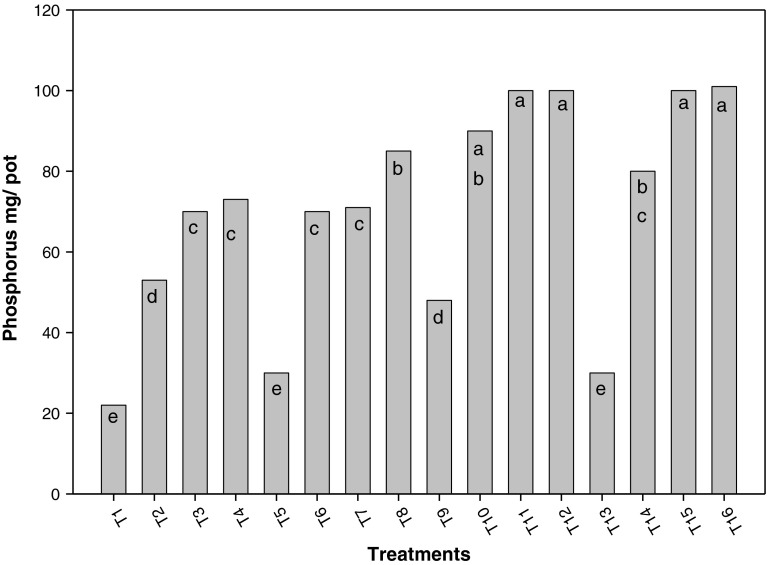

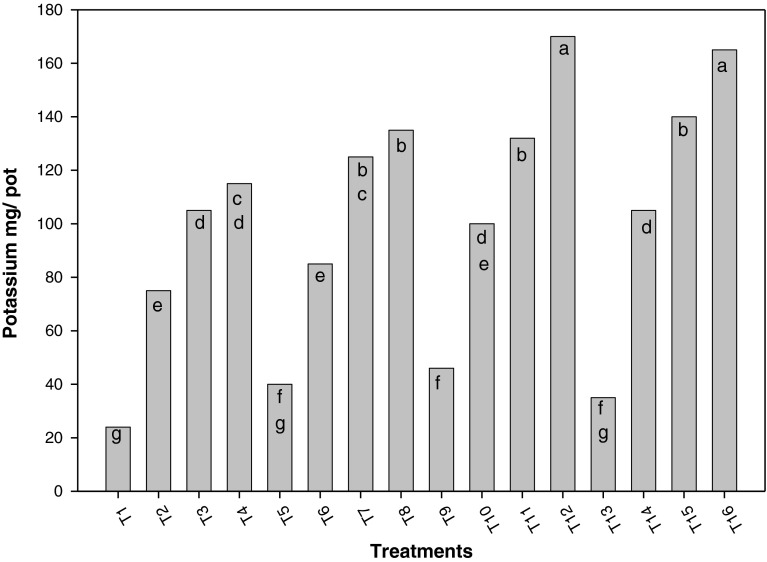

Figures 5 and 6 show the influence of associated and/or incorporated Azolla on phosphorus and potassium contents in rice plants, with different nitrogen doses, where both nutrients presented similar behavior to that of nitrogen, positively influenced by N fertilization and Azolla. In general, combining both ways of using Azolla surpassed the remaining treatments, followed by variants where Azolla was associated to rice crop, and where fern was incorporated.

Fig. 5.

Influence of associated and incorporated Azolla on phosphorus contents in rice plants with different nitrogen doses a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i shows the significant differences on the basis of Tukey HSD

Fig. 6.

Influence of different treatments on potassium content in rice plants a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i shows the significant differences on the basis of Tukey HSD

When analyzing soil chemical features after incorporating Azolla (Table 3), it could be noticed that treatments did not influence pH, P, Ca and Mg. However, they did influence organic matter and potassium content. In this sense, the highest values were achieved by combining incorporated and associated Azolla, followed by treatments where Azolla was incorporated, leaving the third place of treatments in which the fern was associated to rice crop.

Table 3.

Soil characteristic features after harvesting

| Treatments | pH | OM | P | K | Ca | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 6.70c | 3.91ghi | 65.67abcd | 0.23e | 19.83 | 3.07 |

| T2 | 5.72bc | 3.89hi | 64.33abcd | 0.25cde | 19.67 | 3.67 |

| T3 | 6.72bc | 3.77i | 60.33cd | 0.24e | 20.33 | 3.67 |

| T4 | 6.72bc | 3.67i | 66.67ab | 0.25cde | 19.33 | 3.75 |

| T5 | 6.80ab | 4.47cde | 61.33bcd | 0.34ab | 19.50 | 3.00 |

| T6 | 6.71bc | 4.50cd | 60.00cd | 0.31ab | 19.58 | 3.00 |

| T7 | 6.78abc | 4.85ab | 61.00bcd | 0.29bcd | 19.67 | 3.04 |

| T8 | 6.76abc | 4.73bc | 66.67ab | 0.37a | 19.50 | 3.00 |

| T9 | 6.75abc | 4.70bc | 62.33bcd | 0.35ab | 20.08 | 3.00 |

| T10 | 6.80ab | 4.88ab | 68.67a | 0.31ab | 19.50 | 3.10 |

| T11 | 6.84a | 5.12a | 66.33abc | 0.3b | 19.50 | 3.10 |

| T12 | 6.77abc | 4.13fgh | 62.33bcd | 0.33ab | 19.58 | 3.12 |

| T13 | 6.82a | 4.16fgh | 64.33abcd | 0.24de | 19.33 | 3.04 |

| T14 | 6.80ab | 4.22def | 61.67bcd | 0.20e | 19.58 | 3.58 |

| T15 | 6.82a | 4.28def | 63.67abcd | 0.30bc | 19.25 | 3.54 |

| T16 | 6.77abc | 4.19efg | 69.66a | 0.31b | 19.67 | 3.33 |

a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i shows the significant differences on the basis of Tukey HSD

Discussion

An increase in plant height and number of tillers per plant was seen in the treatments where incorporated and/or associated Azolla was used. The highest value was achieved in treatment T11, where 60 kg ha−1 N was applied to rice plant (Figs. 1, 2). Treatment T9 stood out, in which nitrogen was not applied and both ways of using Azolla were performed. This treatment seems to supply the nitrogen demands of rice plants. In, general terms, such behavior of rice height was caused by the influence of nitrogen content in the medium, which could be supplied through different ways and means, as reported earlier (Singh 1989; Baker 1999; Bhuvaneshwari 2012; Bhuvaneshwari and Kumar 2013).

Like the number of tillers per plant and height, nitrogenous fertilization along with Azolla influenced nitrogen extracted by plants and dry mass production (Figs. 3, 4). Treatments combining both ways of using Azolla tended to produce more biomass than the remaining treatments with the same nitrogen dose. Therefore, combining incorporation and association of this fern not only serve to provide plants with significant amount of nitrogen, but also enables a better use of nitrogen added by mineral fertilization and thereby, a higher dry mass production. Similar results were recorded when A. pinnata was used by Manna and Singh (1990); Baker (2000); Bhuvaneshwari and Singh (2012).

For both above variables, it is highlighted the fact that nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium doses are inadequate for achieving good crop development, however, the influence of incorporated and/or associated Azolla allows a better use of nitrogen and better conditions for assimilating other nutrients, thus improving crop nutrition as reported by Samarajeewa (1999).

Treatment T8 and T12 presented the highest nitrogen concentration in the plants. In both of them, incorporated Azolla and 90 kg ha−1 N were applied. The incorporation of this fern seems to maintain a higher soil nitrogen availability than its association, as observed by other workers (Singh 1989; Fageria et al. 1999; Baker 2000).

Regarding dry mass production and nitrogen content, in treatments where incorporated and associated Azolla were combined, value tended to be higher, compared to other treatments presenting the same nitrogen doses. This is caused by the influence of incorporated and associated Azolla on plant available nitrogen content in the soil, as a result of nitrogen release during fern decomposition, reduction in loss of nitrogen might have occured when applied as N fertilizer and that excreted into water by associated Azolla (de Macale et al. 2002).

Figures 5 and 6 show the influence of associated and incorporated Azolla on phosphorus and potassium contents in rice plants, combining both ways of using Azolla surpassed the remaining treatments, followed by the variants where Azolla was associated to rice crop, and where it was incorporated. This could be due to the influence of supplying these elements where fern is decomposed, as well as the effect on pH provoked by the associated Azolla, which increases the solubility of such elements. It was also reported that Azolla increased fertilizer efficiency, when applied in both ways (Pabby et al. 2004).

The soil chemical features are given in Table 3. Treatments did not influence pH, P, Ca and Mg. However, they did influence organic matter and potassium contents. Organic matter and potassium contents in the soil presented significant differences among treatments; the use of Azolla influenced both of them. The highest values were achieved by combining incorporated and associated Azolla, followed by treatments where Azolla was incorporated, third place was recorded given to the treatment in which fern was associated to rice crop. This is related to the contribution of Azolla after decomposition. Similar results were observed by other researchers (Singh 1979; Baker 1999).

The utilization of Azolla as a green manure benefits rice crop, obtaining the highest response when combining incorporation and association of this fern. It also favors nutrient absorption by rice and increases its yield, as well as organic matter content of the soil.

Acknowledgments

The first author is thankful to the department of science and Technology (DST), WOS-A, New Delhi, India for providing the funds. Thanks are also due to Head of Department of Botany and Prof. H. B. Singh, I.A.S. BHU, Varanasi for rendering laboratory and Net house facility.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this research has no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker ASS (1999) Nitrogen response of a Japonica and Indica variety under irrigated system. Report on experiments in rice research techniques course, vol 3. Tsukuba International center TBIC, Japan, pp 1–20

- Baker R (2000) Experimental result in nitrogen response of rice. Disponible. http://www.3hawaii.edu/-jimi/publications.htm

- Bhuvaneshwari K. Beneficial effects of blue-green algae and Azolla in rice culture. Environ Conserv J. 2012;13(1 & 2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuvaneshwari K, Kumar Ajay. Agronomic potential of the association Azolla-Anabaena. Sci Res Report. 2013;3(1):78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuvaneshwari K, Singh PK. Organic rice production using organic manures and bio inoculants in alkaline soil. J Recent Adv Agric. 2012;1(4):128–134. [Google Scholar]

- de Macale MAR, VIek PLG, San Valentine GD (2002) The role of Azolla cover in improving the nitrogen use efficiency of lowland rice. In: Proceedings of the conference sustaining food security and managing natural resource in Southeast Asia, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- Fageria NK, Baliger VC (1999) Nitrogen management for low land rice production on dinceptisol. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural research Service, Tektran

- Jackson ML. Soil chemical analysis. New Delhi: Prentice Hall of India Pvt Ltd; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson ML. Soil chemical analysis. New Delhi: Prentice Hall of India Pvt Ltd; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Manna AB, Singh PK. Growth and nitrogen fixation of Azolla pinnata and Azolla caroliniana as affected by urea in transplanted and direct seeded rice. Expl Agric. 1990;25:485–497. [Google Scholar]

- Meelu OP, Singh PK (1991) Integrated nutrient management through organic, bio and inorganic fertilization of crops. In: Meelu et al (eds) Micronutrients in soils and crops. Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, pp 156–166

- Pabby A, Prasanna R, Singh PK. Biological significance of Azolla and its utilization in agriculture. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad. 2004;70:299–333. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna R, jaiswal P, Singh YV, Singh PK. Influence of biofertilizers and organic amendments on nitrogenous activity and phototrophic biomass of soil under wheat. Aeta Agronomica Hungarica. 2008;56:149–159. doi: 10.1556/AAgr.56.2008.2.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samarajeewa KBDP (1999) The effect of different timing of top dressing of nitrogen application and Azolla under low light intensity on the yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Report on experiments in rice research techniques course, vol 3. Tsukuba International Centre TBIC, Japan. International Co-operation Agency, Ibaraki, Japan, pp 71–79

- Singh PK. Multiplication and utilization of fern Azolla containing nitrogen fixing symbiont as green manure in rice cultivation. Riso. 1977;26:125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK. Nitrogen and rice. Philippines: International Rice Research Institute; 1979. Use of Azolla in rice production in India; pp. 407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK. Use of Azolla in Asian agriculture. Appl Agric Res. 1989;4:149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Singh DP, Singh PK. Growth and nitrogen fixation of Azolla pinnata and its effect on rice crop when incubated in different quantities after transplanting on rice. Thai J Agric Sci. 1989;22:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Singh DP, Singh PK. Response of Azolla caroliniana and rice to phosphorous enrichment of the Azolla inoculum and phosphorous fertilization during intercropping. Expt Agric. 1995;31:21–26. doi: 10.1017/S0014479700024972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spore (1992) Azolla a nitrogen source of rice farmers Bulletin of CTA no. 40 (CTA spore1992, 16P) Bimonthly bulletin of the technical center for agriculture and rural cooperation 40, p 5

- Watanabe I (1982) Azolla Anabaena symbiosis—its physiology and use in tropical agriculture. In: Microbiology of tropical soil and plant productivity developments in plant and soil science, vol 5, pp 169–185

- Watanabe I, Ventura W, Mascarina G, Eskew DL. Fate of Azolla sp. and urea nitrogen applied to wetland rice (Oryza sativa L.) Biol Fertil Soils. 1989;8:102–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00257752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]