Significance

Although the multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii is a serious threat for health care systems worldwide, very little is known about the mechanisms that have facilitated its rise as a successful pathogen. Our work demonstrates that multiple MDR A. baumannii strains regulate the expression of their type VI secretion system (T6SS), an antibacterial apparatus used to kill other bacteria, by harboring a large, self-transmissible resistance plasmid containing T6SS regulatory genes. Through spontaneous plasmid loss, A. baumannii activates its T6SS and is able to outcompete other bacteria. However, this comes at a cost, as these strains lose resistance to antibiotics. This mechanism constitutes an apparent survival strategy by A. baumannii and provides insights into the pathobiology of this important pathogen.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, Acinetobacter baumannii, T6SS, bacterial secretion, plasmid

Abstract

Infections with Acinetobacter baumannii, one of the most troublesome and least studied multidrug-resistant superbugs, are increasing at alarming rates. A. baumannii encodes a type VI secretion system (T6SS), an antibacterial apparatus of Gram-negative bacteria used to kill competitors. Expression of the T6SS varies among different strains of A. baumannii, for which the regulatory mechanisms are unknown. Here, we show that several multidrug-resistant strains of A. baumannii harbor a large, self-transmissible resistance plasmid that carries the negative regulators for T6SS. T6SS activity is silenced in plasmid-containing, antibiotic-resistant cells, while part of the population undergoes frequent plasmid loss and activation of the T6SS. This activation results in T6SS-mediated killing of competing bacteria but renders A. baumannii susceptible to antibiotics. Our data show that a plasmid that has evolved to harbor antibiotic resistance genes plays a role in the differentiation of cells specialized in the elimination of competing bacteria.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria that cause hospital-acquired infections are a mounting concern for health care systems globally (1). Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Acinetobacter baumannii is emerging as a frequent cause of difficult-to-treat nosocomial infections, and some isolates are resistant to all clinically relevant antibiotics (2, 3). A. baumannii is often isolated from polymicrobial infections and therefore spends at least a part of its time competing with other bacteria (4). Antagonistic interactions between bacteria manifest in a variety of different ways (5), and the type VI secretion system (T6SS) is a potent weapon used by many Gram-negative bacteria to kill competitors (6–8). The multicomponent T6SS apparatus facilitates a dynamic contact-dependent injection of toxic effector proteins into prey cells (9, 10), and expression of cognate immunity proteins prevents self-inflicted intoxication (9, 11). The T6SS is composed of several conserved proteins involved in the formation of the secretory apparatus (12, 13). One of these components, hemolysin-coregulated protein (Hcp), forms hexameric tubule structures that are robustly secreted to the culture supernatants in bacteria with an active T6SS, allowing it to be used as a molecular marker for T6SS activity (6, 14).

T6SS is a dynamic apparatus (15). Its biogenesis follows energetically costly cycles of assembly/disassembly, and therefore, in most bacteria, T6SS appears to be exquisitely regulated. T6SS is silenced in most strains and only activated under specific conditions, such as an attack from another bacterium or in environments leading to membrane perturbations (16–19). Many Acinetobacter spp. encode the genes for a T6SS, including Acinetobacter noscomialis and Acinetobacter baylyi, which possess a constitutively active antibacterial T6SS (20–24). A. baumannii strains have been shown by us and others to secrete Hcp (21, 25), but to our knowledge a T6SS-dependent phenotype has not been ascribed to this species. Furthermore, our previous results showed that Hcp secretion is highly variable between A. baumannii strains, with some isolates carrying an inactive system (21). The precise regulatory mechanism(s) underlying T6SS suppression in some A. baumannii is unknown.

Here, we show that a large resistance plasmid of A. baumannii functions to repress the T6SS by encoding negative regulators of its activity. Analysis of colonies from a clinical isolate showed that the plasmid is readily lost in a subset of the population. This leads to the activation of the T6SS, which imparts the ability to kill other bacteria, with the simultaneous loss of antibiotic resistance. We propose that the differentiation into T6SS+ MDR– and T6SS– MDR+ phenotypes may constitute a novel survival strategy of this organism.

Results

Individual Colonies of a MDR Clinical A. baumannii Isolate Show an On–Off T6SS Phenotype That Correlates with a Loss of DNA and Antibiotic Resistance.

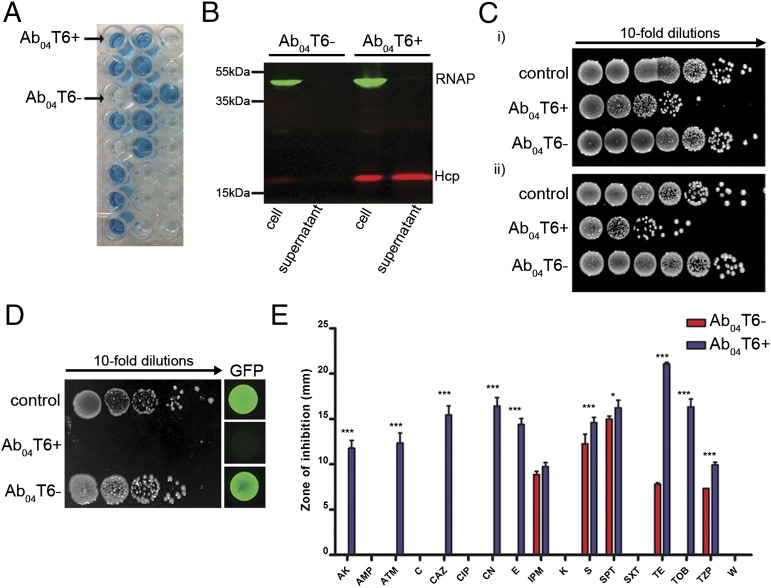

To determine the regulatory mechanisms involved in A. baumannii T6SS, the Hcp secretion profile of an MDR clinical isolate that caused a recent outbreak (26) was assessed by an Hcp-ELISA (21). We found that individual colonies from a single patient isolate (Ab04) displayed two contrasting Hcp secretion profiles (Fig. 1A), which were verified by Western blot (Fig. 1B). Colonies displaying robust Hcp secretion profiles were considered T6SS+ (Ab04T6+), whereas those with no detectable Hcp secretion were considered T6SS– (Ab04T6–). Ab04 caused a clonal outbreak that originated from an index patient who was also coinfected with Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae (26). Ab04T6+, but not Ab04T6–, caused a considerable reduction in survival of these E. coli and K. pneumoniae coisolates in competition assays (Fig. 1C). The killing ability of Ab04T6+ was further confirmed with common laboratory E. coli strains as prey (Fig. 1D). Note that, although bactericidal activity is not formally shown in the competition assays, we use the term “killing,” as broadly used for Acinetobacter T6SS activity in previous studies (16, 23).

Fig. 1.

Outbreak isolate A. baumannii Ab04 displays an on/off T6SS phenotype concomitant with a loss of antibiotic resistance. (A) Detection of Hcp secretion from individual colonies of A. baumannii Ab04 (Ab04) by Hcp-ELISA. Ab04T6+ and Ab04T6– labels indicate the typical readout of colonies giving rise to robust or undetectable levels of Hcp secretion, respectively. (B) Hcp secretion (red) profiles of Ab04T6+ and Ab04T6– colonies were confirmed by Western blot on whole cells and supernatants, with RNA polymerase (RNAP; green) as the lysis control. (C) Recovery of surviving clinical isolates of E. coli (i) or K. pneumoniae (ii), coisolated during A. baumannii outbreak, after coincubation with Ab04T6+, Ab04T6–, or control strain. (D) Recovery of surviving E. coli MG1655R after incubation with Ab04T6–, Ab04T6+, or a rifampicin-sensitive E. coli strain (control). GFP images were produced using an E. coli strain constitutively expressing GFP as prey, and representative images from a single experiment are shown. (E) Antibiotic susceptibilities of Ab04T6– and Ab04T6+ as assessed by disk diffusion assay. Antibiotic abbreviations are listed in Materials and Methods. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05.

To identify the genetic difference(s) responsible for the discrepancy in T6SS phenotypes, we used Illumina sequencing to generate draft genomes for Ab04T6– and Ab04T6+. Analysis of the de novo assembled genomes revealed that Ab04T6+ contained a noticeably smaller genome than Ab04T6–, lacking a total of ∼170 kb of DNA. Some of the genes encoded by this DNA contained putative antibiotic resistance genes. We determined that Ab04T6+ lost resistance to several classes of clinically important antibiotics, including β-lactams (aztreonam and ceftazidime), aminoglycosides (gentamicin, amikacin, and tobramycin), the macrolide erythromycin, and tetracycline (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1). These results suggested that Ab04T6+ had undergone some form of DNA loss, leading to antibiotic susceptibility and T6SS activation.

Fig. S1.

Antibiotic resistance loss by T6+ strains. Antibiotic resistance was assessed by disk diffusion for T6– and T6+ variants of the three strains. Images here show typical results, which are presented in graphical form in Fig. 1 and Fig. S3.

DNA Loss Leading to T6SS Activation and Antibiotic Susceptibility Is Widespread in A. baumannii.

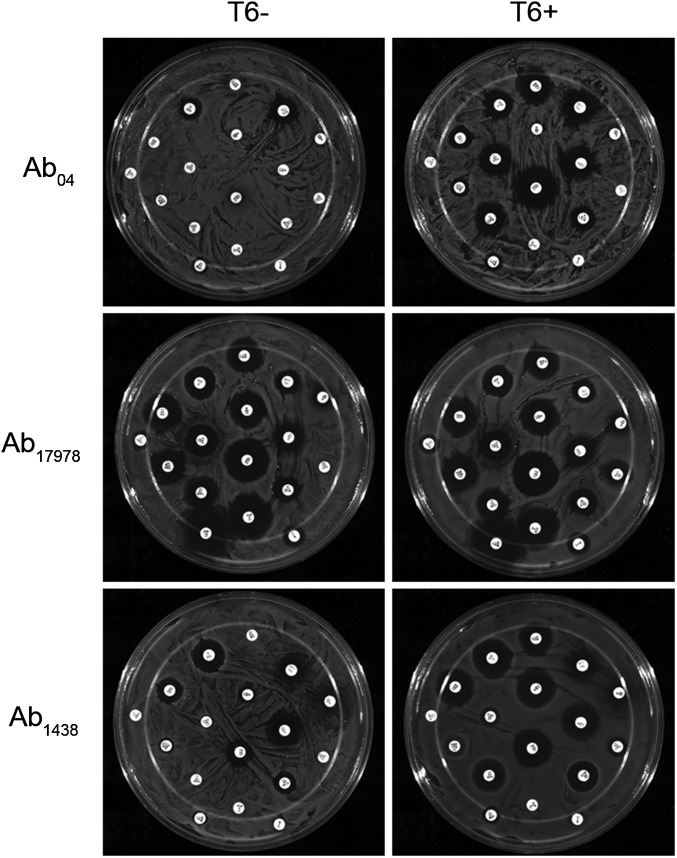

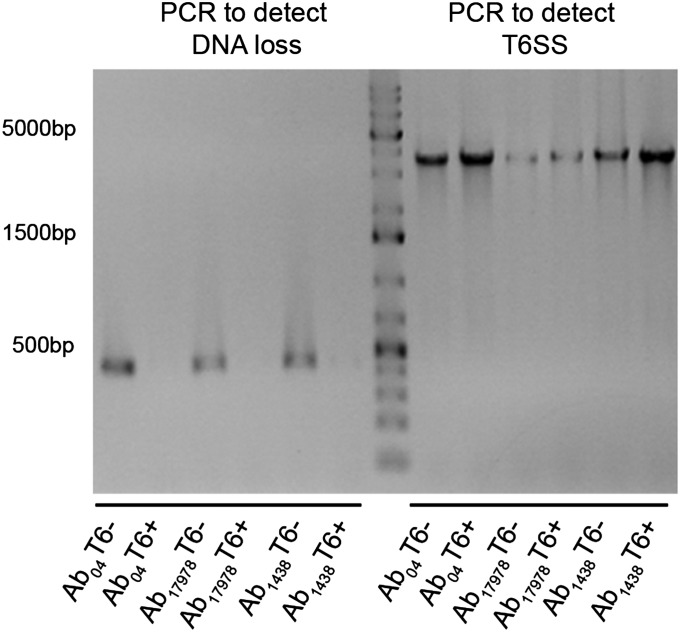

We speculated that the DNA missing in Ab04T6+ may be present in other A. baumannii strains. We used a combination of PCR and bioinformatic methods to identify other A. baumannii strains harboring this additional DNA. Two strains were identified by a positive PCR specific for the missing DNA (Fig. S2). These were the sequenced and well-characterized reference strain A. baumannii ATCC 17978 (Ab17978), which was isolated in the early 1950s, before the introduction of many common antibiotics, and is considered a relatively drug-sensitive strain, and a recent MDR clinical isolate from Argentina, A. baumannii 1438 (Ab1438). In agreement with the PCR results, homology searches of A. baumannii genome sequences revealed several other strains possessing this DNA, including Ab17978 (Table S1). Using the Hcp-ELISA, bacteria from Ab17978 and Ab1438 displaying an on/off phenotype for T6SS were isolated (Fig. S3). Although the T6SS locus was present in both cell types, the T6+ variants did not yield the PCR product detectable in the T6– strains (Fig. S2). In contrast to their T6– counterparts, Ab17978T6+ and Ab1438T6+ efficiently killed E. coli in competition assays (Fig. S3). This killing was dependent on a functional T6SS, as Ab17978T6+ lacking essential T6SS components hcp or tssM did not kill E. coli (Fig. 2). Because Ab04T6+ had lost antibiotic resistance, we compared the resistance profiles of Ab1438T6–/T6+ and Ab17978T6–/T6+. Ab1438T6+ showed a significant decrease in resistance to several antibiotics compared with Ab1438T6–, and Ab17978T6+ lost resistance to the combination of sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (S/T) compared with Ab17978T6– (Figs. S1 and S3).

Fig. S2.

PCR detection of DNA present in T6– but not T6+ strains indicates DNA loss in Ab17978 and Ab1438. Primers (Node_182F and Node_182R) were designed, based on Illumina data from Ab04T6–, to amplify a ∼400-bp fragment of DNA present in Ab04T6– but not Ab04T6+ (left side of gel). Strains Ab17978 and Ab1438 also yielded this PCR product, which was only present in the T6– variants. Primers T6SSF and T6SSR were used to confirm that all strains still possessed the T6SS locus (right side of gel).

Table S1.

A. baumannii strains that contain DNA sequences with homology to pAB3 and pAB04-1

| Strain | Plasmid? | GenBank accession |

| A. baumannii ATCC 17978 | Yes/no*; plasmid pAB3 | CP000521.1* |

| A. baumannii IOMTU433 | Yes; plasmid pIOMTU433 | AP014650.1 |

| A. baumannii OIFC109 | Yes; plasmid pOIFC109-122 | ALAL01000013.1 |

| A. baumannii OIFC137 | Yes; plasmid pOIFC137-122 | AFDK01000004.1 |

| A. baumannii OIFC143 | Yes; plasmid pOIFC143-128 | AFDL01000008.1 |

| A. baumannii Naval-18 | Yes; plasmid pNaval18-131 | AFDA02000009.1 |

| A. baumannii 233846 | Not indicated | JMOG01000034.1 |

| A. baumannii 318814 | Not indicated | JFEQ01000014.1 |

| A. baumannii 1419130 | Not indicated | JEWL01000060.1 |

| A. baumannii CI79 | Not indicated | AVOD01000009.1 |

| A. baumannii CI86 | Not indicated | AVOB01000033.1 |

| A. baumannii NIPH 527 | Not indicated | APQW01000030.1 |

| A. baumannii WC-348 | Not indicated | AMZT01000015.1 |

| A. baumannii IS-116 | Not indicated | AMGF01000021.1 |

| A. baumannii OIFC065 | Not indicated | AMFV01000043.1 |

| A. baumannii OIFC0162 | Not indicated | AMFH01000054.1 |

| A. baumannii Naval-13 | Not indicated | AMDR01000015.1 |

| Acinetobacter sp. NCTC 10304 | Not indicated | AIEE01000255.1 |

| A. baumannii AB5256 | Not indicated | AHAI01000050.1 |

Integrated into chromosome in original sequence (29).

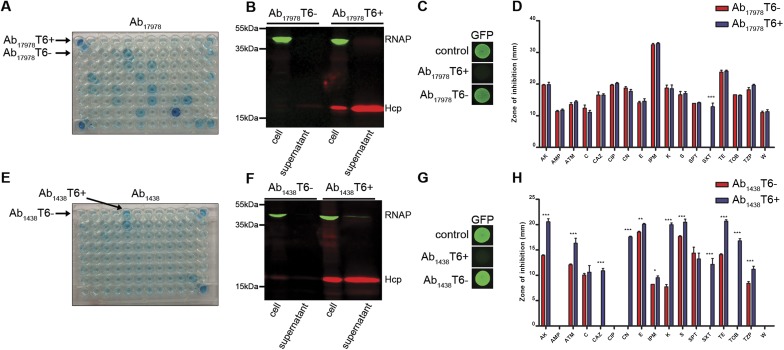

Fig. S3.

Intercolony variation in T6SS and antibiotic resistance is common in A. baumannii. (A and E) Detection of Hcp secretion from individual colonies of A. baumannii ATCC 17978 (Ab17978) and A. baumannii 1438 (Ab1438) by Hcp-ELISA, with colonies giving rise to a T6+ (Ab17978T6+, Ab1438T6+) or T6– (Ab17978T6–, Ab1438T6–) readout indicated. (B and F) ELISA results confirmed by Western blot. (C and G) Survival of GFP-expressing E. coli, as assessed by fluorescence, after incubation with T6+ or T6– variants of Ab17978 and Ab1438, or with non-GFP parental strain (control). Representative images from a single experiment are shown. (D and H) Antibiotic susceptibilities of Ab17978T6+/T6– and Ab1438T6+/T6– as assessed by a disk diffusion assay. Antibiotic abbreviations are listed in Materials and Methods. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05.

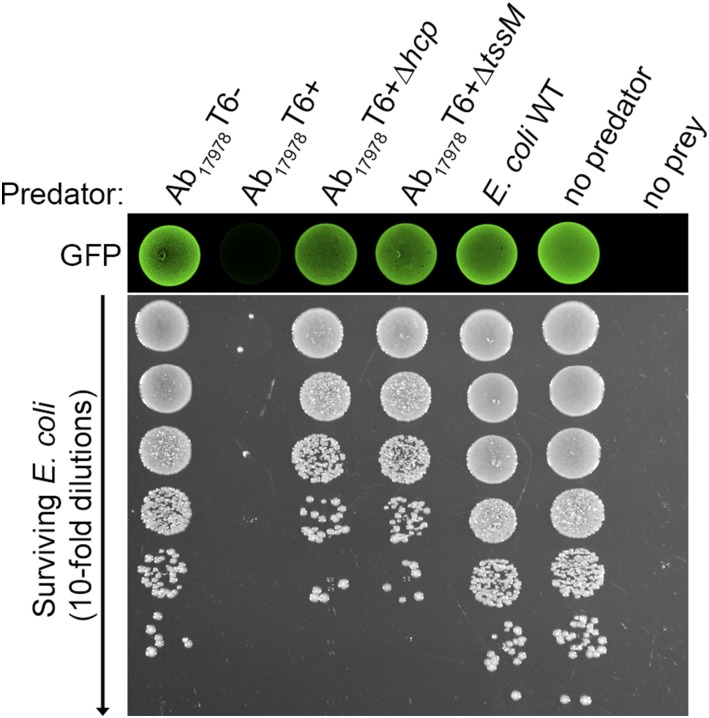

Fig. 2.

Bacterial killing is dependent on a functional T6SS. Survival of GFP-expressing E. coli, as assessed by fluorescence and antibiotic selection, after incubation with various strains of Ab17978, including the T6SS mutants Ab17978∆hcp and Ab17978∆tssM. E. coli WT indicates the parental strain lacking the GFP expression vector and is the no prey control. E. coli was selected for in serial dilutions using kanamycin.

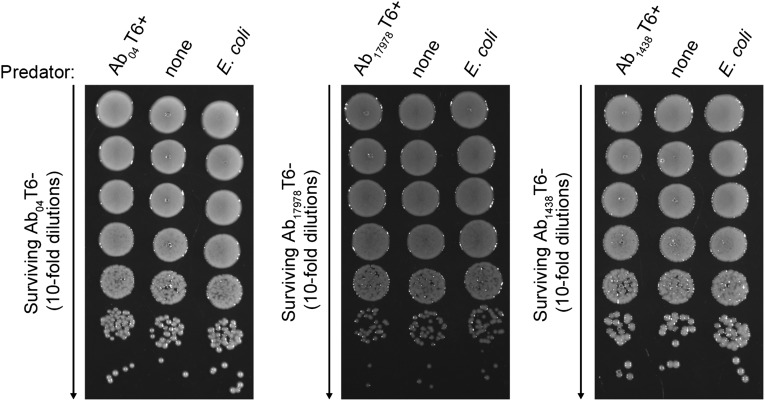

Although the A. baumannii T6SS effector–immunity pairs have not been characterized, activation of the T6SS in the T6+ strains could pose a threat to neighboring T6– sister cells. Through competition assays between T6+/T6– counterparts, we found that T6– cells were not affected by their T6+ kin (Fig. S4). This could indicate that A. baumannii is not capable of self-targeting or that the immunity proteins protecting from T6SS-mediated attacks are produced even under T6– conditions. Given findings in Vibrio cholerae, in which immunity proteins are transcribed constitutively and independently of other T6SS genes (27), we favor the latter hypothesis. This is further supported by our experiments showing that T6+ A. baumannii is able to kill nonkin T6– cells (Fig. S5), which implies that lack of kin-cell killing is due to immunity and not an inability to target another A. baumannii cell. Furthermore, this suggests that effector–immunity pairs are diverse among A. baumannii isolates.

Fig. S4.

T6– A. baumannii is not killed by T6+ sister cells. Survival of indicated T6– A. baumannii after incubation with T6+ counterpart or controls is shown. T6– strains were selected based on difference in antibiotic resistance with their T6+ kin.

Fig. S5.

T6+ A. baumannii kill nonkin T6– A. baumannii. (A) Coincubation of Ab04T6– with indicated predator strains at a 1:2 predator-to-prey ratio. Surviving Ab04T6– was determined by serial dilutions on gentamicin-containing plates. The no predator and no prey controls indicate Ab04T6– or Ab17978T6– plated without the competitor, respectively. (B) Coincubation of a rifampicin-resistant derivative of Ab17978T6– with indicated predator strains at a 5:1 predator-to-prey ratio. Surviving Ab17978T6– was determined by plating on rifampicin. The no predator and no prey controls indicate rifampicin-resistant Ab17978T6– or Ab04T6– plated without the competitor, respectively. Note that Ab04T6– displays a low level of spontaneous resistance.

Loss of a Conserved, Conjugative Resistance Plasmid Results in T6SS Activation.

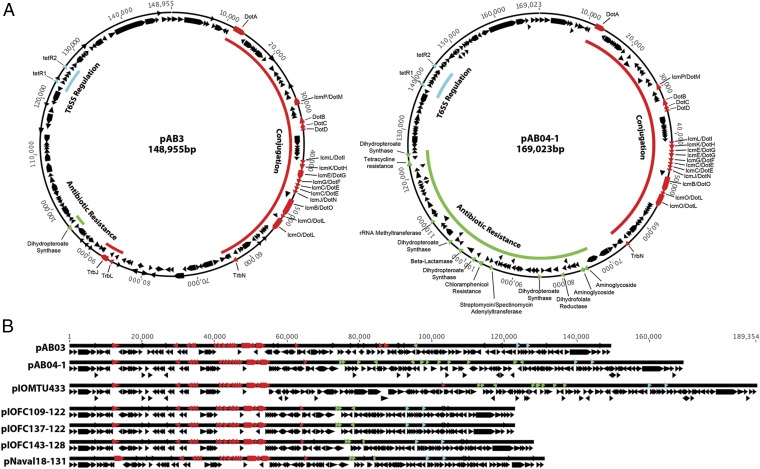

To fully elucidate the genetic changes underlying the observed phenotypes, we sequenced the genomes of Ab04T6+, Ab04T6–, Ab17978T6+, and Ab17978T6– using PacBio long read technology (28). Ab04T6– and Ab04T6+ genomes were completely closed and identical, except for the presence of a 170-kb plasmid (pAB04-1) present only in Ab04T6– (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the only detectable difference between Ab17978T6– and Ab17978T6+ was the presence of a 150-kbp plasmid (pAB3) in Ab17978T6– (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, pAB3 was assembled as part of the chromosome in the original genome sequencing of Ab17978 (29). This may be the result of prior genome assembly errors or possibly plasmid integration in the chromosome, although we observed no evidence of integration in our sequence data. Additionally, Illumina sequencing reads from Ab1438T6–, but not from Ab1438T6+, aligned onto pAB04-1 and pAB3 with considerable sequence coverage (Fig. S6).

Fig. 3.

A. baumannii plasmids share common structural features. (A) Assembled plasmids from PacBio sequencing of Ab17978T6– (pAB3, accession no. CP012005) and Ab04T6– (pAB04-1, accession no. CP012007) and other plasmids taken from GenBank (B), highlighting common conjugation (red), antibiotic resistance (green), and T6SS regulation (blue) loci.

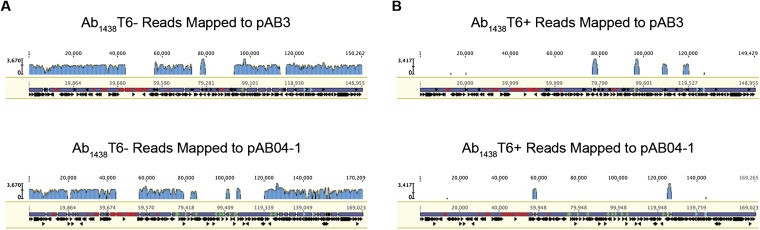

Fig. S6.

Illumina reads from Ab1438T6–, but not Ab1438T6+, map onto pAB03 and pAB04-1. (A and B) Sequencing reads from Ab1438T6– map well onto both pAB03 and pAB04-1, whereas very few reads from Ab1438T6+ do. The small regions of mapped reads of Ab1438T6+ are mobile element regions that are also found elsewhere in the genomes.

pAB04-1 and pAB3 are highly similar over much of their sequence and seem to share a common backbone that includes a putative conjugative T4SS. pAB04-1 contains a large island with several antibiotic resistance genes that are absent in pAB3. DNA sequences corresponding to similar plasmids are present in many other recent MDR isolates of A. baumannii (Fig. 3B). Considering that pAB3 is from an “old” isolate, this suggests that pAB3 could be considered as an ancestral form of these current plasmids, which encode more resistance genes (Fig. 3 A and B and Table S1). Through conjugation experiments, we determined that pAB3 could be transferred from Ab17978T6– to Ab17978T6+, resulting in gain of antibiotic resistance and suppression of the T6SS in transconjugants (Fig. S7). This indicates that the T4SS contained in pAB3 is functional and that this plasmid can be disseminated among Acinetobacter strains.

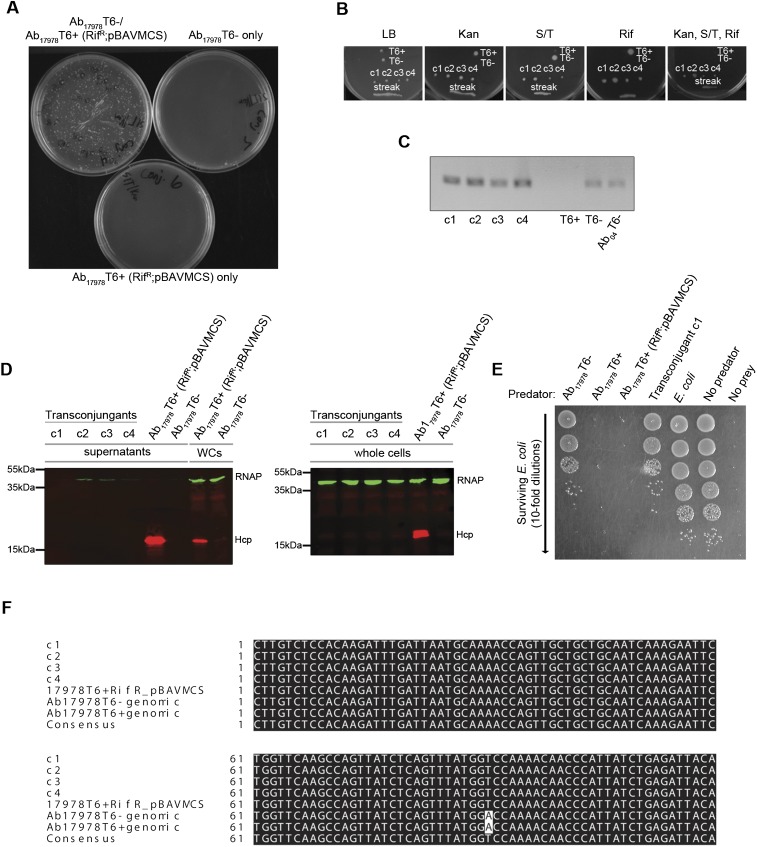

Fig. S7.

pAB3 is self-transmissible from Ab17978T6– to Ab17978T6+ and shuts down T6SS in transconjugants. (A) Putative transconjugant colonies were obtained on plates containing kanamycin (Kan) and S/T when Ab17978T6– was coincubated with a spontaneous rifampicin-resistant strain of Ab17978T6+ harboring the Kan resistance plasmid pBAVMCS [Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS)], and the mixture was plated after overnight incubation, but not when either was incubated alone. Only Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS) that obtained pAB3, which imparts S/T resistance, is expected to grow. (B) Individual transconjugant colonies (c1–c4) or a loop full of transconjugants (streak) were replica plated onto various antibiotics. Only transconjugants grew on the combination plate of Kan, S/T, and Rif. (C) PCR detection of pAB3 using primer Node_182F/R. (D) Hcp expression and secretion is repressed in transconjugants. (E) Transconjugants are unable to kill E. coli in a bacterial killing assay. Predators are as listed, with an antibiotic sensitive E. coli strain used as a control. (F) Confirmation that c1–c4 are true transconjugants by PCR and sequencing of the rpoB gene. Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS) and c1–c4 all have a nucleotide difference in their rpoB gene, giving rise to RifR, whereas the parental Ab17978T6+ genomic and Ab17978T6– genomic are identical, indicating that c1–c4 are all truly Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS) harboring pAB3.

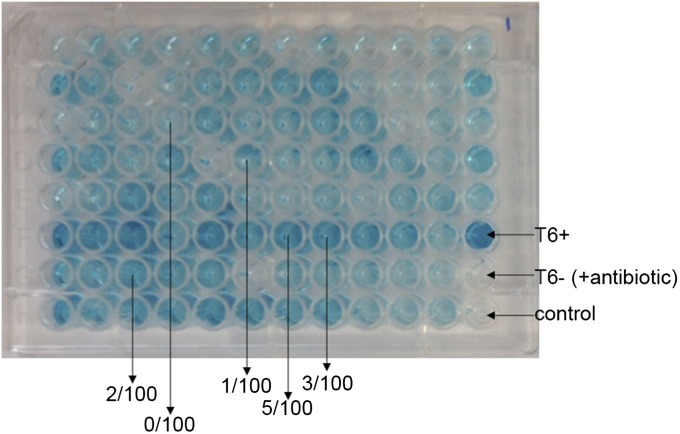

To estimate the frequency of plasmid loss, we plated Ab17978 in the presence of T/S (to ensure plasmid maintenance) and then inoculated single colonies into 96-well plates lacking antibiotics. Wells exhibiting diverse Hcp secretion levels were observed (Fig. S8). About 100 clones of the bacteria contained in representative wells were plated in the presence and absence of antibiotics, and the number of antibiotic-sensitive bacteria was counted, with plasmid loss confirmed by PCR. We estimated that, in our experimental conditions, the percentage of cells lacking the plasmid ranges from 0% to 5% of a given population.

Fig. S8.

Plasmid loss rates in Ab17978. Individual colonies of plasmid-containing Ab17978T6– were inoculated into 96-well plates containing antibiotic-free growth medium. Supernatants were collected for Hcp-ELISA, which identified a wide range of Hcp secretion phenotypes. We selected several representative wells and determined the proportion of Ab17978 that had lost the plasmid by replica plating and PCR.

Two Plasmid-Encoded TetR-Like Regulators Suppress the A. baumannii T6SS.

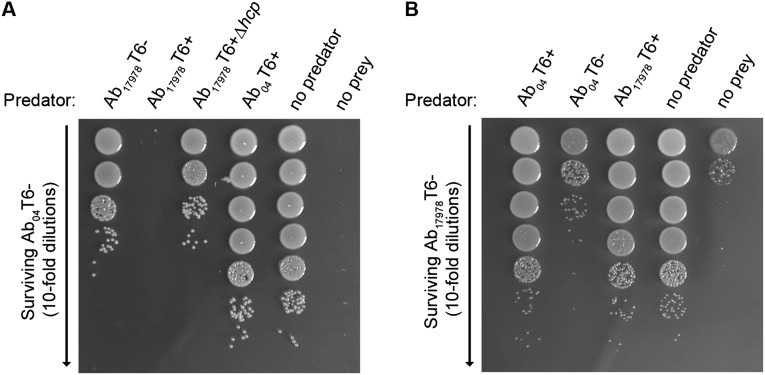

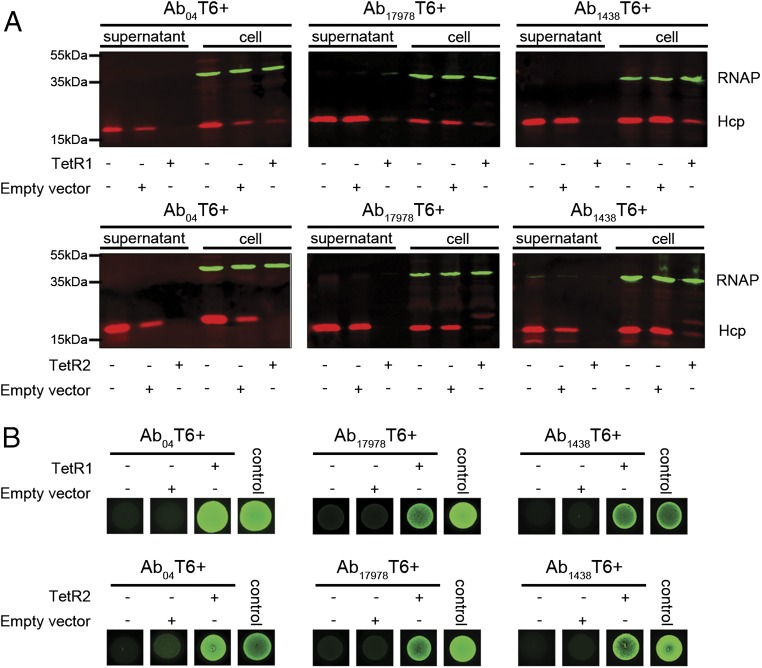

Because of their similar backbone, we reasoned that the plasmids possessed by T6– A. baumannii strains likely contained a genetic element that was responsible for T6SS repression. Each plasmid encodes several conserved predicted regulator genes, including an hns-like gene (locus tag ACX61_19730) and two tetR-like regulators, tetR-like1 and tetR-like2 (tetR1 and tetR2, locus tags ACX61_19730 and ACX61_19655, respectively) (Fig. 3 A and B). H-NS proteins are a family of global regulators that bind A-T–rich regions and are usually used to silence horizontally acquired genes (30). Proteins within the H-NS family have been suggested to be involved in T6SS regulation (31, 32). TetR-like regulators play a broad role in many aspects of prokaryotic physiology (33), and members of this family have been implicated in T6SS regulation (34). Close homologs of TetR1 and TetR2 are only present in A. baumannii harboring pAB04-1/pAB3-like plasmids. The hns, tetR1, and tetR2 genes were cloned and ectopically expressed in the three T6+ strains to test their effect on T6SS. We observed no change in Hcp expression or secretion in Ab04T6+ carrying the hns-like gene (Fig. S9). In contrast, introduction of TetR1 or TetR2 dramatically decreased expression and secretion of Hcp in all T6+ strains (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, TetR1 and TetR2 abolished Hcp expression and secretion in A. baumannii ATCC 19606 and A. baylyi ADP1, both of which possess a constitutively active T6SS under laboratory conditions but had no effect on V. cholerae T6SS (Fig. S9). In killing assays, T6+ strains expressing either TetR1 or TetR2 showed an impaired ability to kill E. coli, consistent with a defect in Hcp secretion (Fig. 4B).

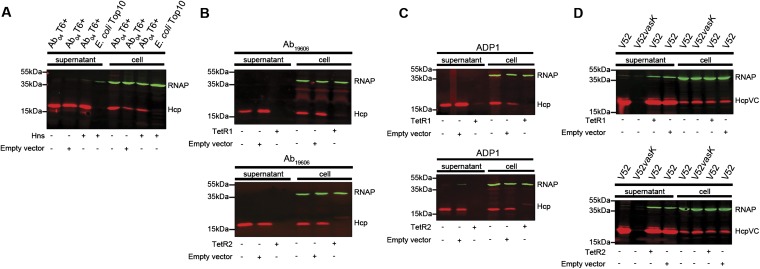

Fig. S9.

Plasmid-encoded TetR1 and TetR2, but not an Hns-like protein, repress the T6SS in Acinetobacter but have no effect on V. cholerae. (A) Detection of Hcp expression (cell) and secretion (supernatant) in Ab04T6+ expressing an Hns-like (Hns) protein encoded on the pAB04-1, with RNA polymerase (RNAP) as a loading and lysis control. (B–D) Expression and secretion of Hcp by TetR1 (Upper) and TetR2 (Lower) expressing A. baumannii ATCC 19606 (B), A. baylyi ADP1 (C), and V. cholerae V52 (D). The V. cholerae Hcp (HcpVC) was detected using an anti-HcpVC antibody, and the T6SS vasK mutant strain was included as a secretion control.

Fig. 4.

Plasmid-encoded TetR1 and TetR2 repress the T6SS. (A) Detection of Hcp (Red) expression and secretion in Ab04T6+, Ab17978T6+, and Ab11438T6+ expressing TetR1 (Upper panels) or TetR2 (Lower panels), with RNA polymerase (RNAP; green) as a lysis control. (B) Survival of GFP-expressing E. coli, as assessed by fluorescence, after coincubation with TetR1 (Upper panels) or TetR2 (Lower panels) expressing A. baumannii strains. Control spot consists of GFP-expressing E. coli incubated with non-GFP parental strain, and representative images from a single experiment are shown.

Discussion

In this study, we uncovered the molecular mechanisms leading to the repression of T6SS in A. baumannii. Our work suggests an explanation for the differences in T6SS activity observed among different strains of A. baumannii (21). By screening different colonies from a MDR clinical isolate, we discovered that A. baumannii cells can present an on/off T6SS phenotype that is controlled by the presence or absence of a resistance plasmid that carries the repressors of the secretion system. Indeed two repressors belonging to the TetR family, both individually capable of repressing the T6SS, are encoded in the plasmid. We have identified this plasmid in clinical isolates from geographically diverse locations around the world and also in the Ab17978, one of the most commonly used strains in laboratories that was isolated in the 1950s. Upon plasmid loss, which occurs frequently in the absence of selection, the cells differentiate into T6+ bacteria specialized in the elimination of competing bacteria. Those cells that keep the plasmid maintain the T6SS in a silent state but retain the ability to resist antibiotics. It is conceivable that a ligand(s) for the TetR proteins exists that would relieve T6SS repression without the loss of the resistance plasmid. However, our data suggest that A. baumannii loses this plasmid readily without antibiotic selection, indicating plasmid loss is a true mechanism for T6SS activation. In the human host, plasmid loss has been documented in A. baumannii strains isolated from the same patient over time (35). Furthermore, the finding that this plasmid can be conjugated from a T6– cell to a T6+ cell raises the possibility that the plasmid can be disseminated back into those cells that have lost it. In a previous work, we reported that although Hcp secretion was detectable in A. baumannii 17978, T6SS was not used to kill other bacteria (21). We believe that the use of a mixed population T6SS+/T6SS– in that study masked the activity of the T6SS in this strain. It is conceivable that other reports using strains harboring the plasmid may also be biased by the use of mixed populations.

The observation that the TetR repressors can act on T6SS in a wide range of A. baumannii strains and species suggests they operate on a conserved component found across Acinetobacters. This may not be surprising, given the high sequence conservation of T6SS loci in these organisms (21, 22). It remains unknown whether A. baumannii strains with a constitutively active T6SS, like A. baumannii ATCC 19606 and A. baumannii SDF (21, 25) (which do not harbor a similar plasmid), at some point (whether during laboratory culture or before isolation) lost an analogous plasmid to those described here, leading to T6SS activation, or whether this plasmid was independently acquired by strains like Ab17978 and Ab04, silencing their previously active T6SS. The finding that these plasmids are highly conserved and apparently only present in A. baumannii suggests that this method of regulation is restricted to Acinetobacter. Our data also show that T6– A. baumannii are resistant to T6SS-mediated attack from T6+ sister cells but not from nonkin T6+ A. baumannii. This indicates that the immunity proteins involved in preventing self-intoxication are produced even when the secretory apparatus itself is not expressed, analogous to the scenario described in V. cholerae (27). However, at this time the effector–immunity pairs of A. baumannii have not been characterized, and as such direct experimental evidence of this remains to be seen.

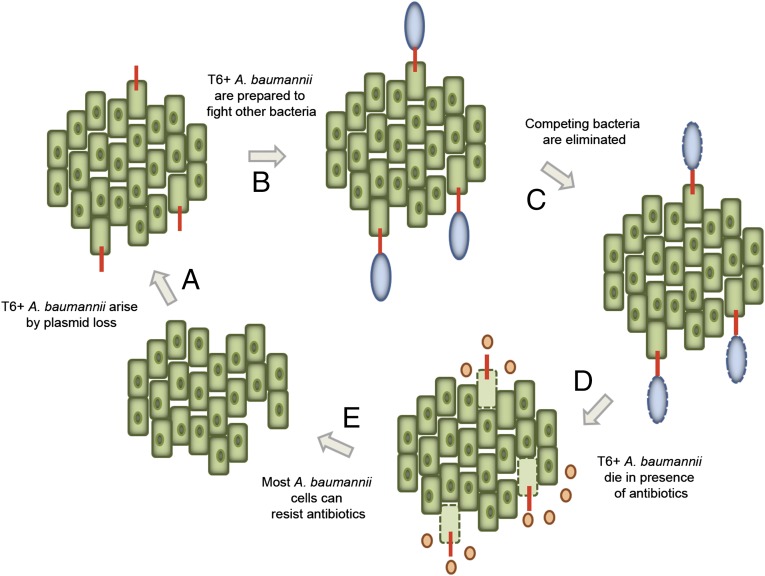

It has been demonstrated that antibiotic resistance-carrying plasmids can impose a fitness cost on their bacterial hosts (reviewed in ref. 36). Furthermore, as has been shown for Salmonella typhimurium, expression of a secretion system can be costly and reduce the competitive fitness of an organism in environments where the secretory apparatus is not beneficial (37). Our results suggest that A. baumannii has partitioned two phenotypes: an ability to resist being killed by antibiotics, and an ability to kill using its T6SS. For the strains and conditions tested in this study, these phenotypes are mutually exclusive. It is tempting to speculate that A. baumannii has evolved the strategy of carrying the T6SS repressors in a frequently lost MDR plasmid as a response to fitness defects imposed by harboring both a large resistance plasmid and a constitutively active T6SS. We suggest a model for the relationship between MDR and T6SS that allows A. baumannii to maintain both systems while avoiding potential deleterious effects (Fig. 5). When MDR A. baumannii is not under the threat of antibiotics, such as in the inanimate hospital environment or an untreated polymicrobial infection, there is an increased likelihood of encountering competitors. In this instance, repression of T6SS is relieved in a subset of the bacterial population by plasmid loss, allowing A. baumannii to actively attack other bacteria. Under conditions where antibiotics are present, MDR A. baumannii may derive enough of a survival advantage from antibiotic resistance alone that an active T6SS is neither necessary nor beneficial (35). In fact, genome sequencing of several recent MDR A. baumannii isolates revealed that some lack a full T6SS locus, suggesting some strains have inactivated their secretion system in favor of antibiotic resistance (35, 38, 39). The plasmid present in the old isolate Ab17978 strain encodes a single antibiotic resistance. The fitness cost of this does not seem to justify the use of the plasmid as a molecular switch for T6SS; however, it is possible that loss of the T6SS-repressing plasmid provides other advantage(s). The plasmids encode about 150 genes, including several other regulators such as H-NS, whose functions remain to be elucidated. It is conceivable that these control other important metabolic pathways or virulence mechanisms in A. baumannii. The antibiotic cassettes appear to be a later addition to the plasmid, and the fact that in only a few decades the number of antibiotic resistance cassettes has increased from 1 up to 11 demonstrates that insertion of resistance cassettes in an “easy-to-lose” plasmid containing the repressors of T6SS is a very efficient strategy to accumulate MDR. An alternative view is that encoding T6SS repressors in the plasmid prevents T6SS-mediated killing of potential recipients, facilitating plasmid propagation among different Acinetobacter strains. In the context of hospital environments, the encounter of A. baumannii with antibiotics is inevitable, and therefore plasmid loss could be regarded as an altruistic mechanism to differentiate cells specialized for elimination of competing bacteria. The interplay between T6SS and antibiotic resistance may constitute an important survival strategy for this nosocomial pathogen.

Fig. 5.

A model for MDR and T6SS in A. baumannii. A. baumannii harbors a MDR plasmid that encodes repressors of T6SS. In the absence of antibiotics, this plasmid is lost in a subset of the population and results in T6SS activation (A). The activation of the T6SS prepares A. baumannii for competition (B) and imparts the ability to kill other bacteria that may try to enter the same environment (C). Upon (re)introduction of antibiotics, plasmid-less A. baumannii will die (D), and the rest of the A. baumannii cells will be resistant and ensure survival of the population (E).

Materials and Methods

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table S2. Hcp-ELISAs were performed as previously described (21). T6+ strains (Ab04T6+, Ab17978T6+, Ab1438T6+) were isolated by Hcp-ELISA. Bacterial killing assays were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods. Antibiotic resistance profiles were determined by disk diffusion. Antibiotics tested were amikacin (AK), ampicillin (AMP), aztreonam (ATM), chloramphenicol (C), ceftazidime (CAZ), ciprofloxacin (CIP), gentamicin (CN), erythromicin (E), imipenem (IMP), kanamycin (K), streptomycin (S), spectinomycin (SPT), S/T (SXT), tetracycline (TE), tobramycin (TOB), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP), and T. The sequence data for the Ab17978 strain described here and its plasmid pAB3 have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers CP0120004 and CP012005, respectively. The Ab04 strain and its associated plasmid pAB04-1 (as well as a second plasmid, pAB04-2) are available under accession numbers CP012006, CP012007, and CP012008, respectively. The DNA libraries for genomic DNA extracted from Ab04T6–, Ab04T6+, Ab17978T6–, and Ab17978T6+ (DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen) were prepared following the Pacific Biosciences 20 kb Template Preparation Using BluePippin Size-Selection System protocol. We screened our Acinetobacter strain library (∼15 isolates) using primer pairs Node_182F/Node_182R (Table S3) to identify other strains carrying plasmids similar to pAB04-1/pAB3. These primers target a conserved region on the plasmid. We bioinformatically identified other strains by BLAST, using the full pAB04-1/pAB3 plasmids as the query against both the nucleotide collection (nr) database and the whole genome shotgun (wgs) database. All primers used are listed in Table S3. For conjugation experiments, Ab17978T6– was used as the donor and a modified strain of Ab17978T6+ was used as the recipient. A spontaneous rifampicin-resistant mutant of Ab17978T6+ was isolated, into which pBAVMCS (providing kanamycin resistance) was introduced by electroporation, generating Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS). A full description of methods is available in SI Materials and Methods.

Table S2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

| Strains | ||

| A. baumannii Ab04 | Clinical isolate | (26) |

| Ab04T6– | Ab04 containing pAB04, antibiotic resistant, T6SS inactive | This study |

| Ab04T6+ | Ab04 lacking pAB04, antibiotic sensitive, T6SS active | This study |

| A. baumannii ATCC 17978 | Type strain; wild type | ATCC (42) |

| Ab17978T6– | Ab17978 containing pAB3, S/T resistant, T6SS inactive | This study |

| Ab17978T6+ | Ab17978 lacking pAB3, S/T sensitive, T6SS active | This study |

| Ab17978T6+∆hcp | Ab17978 lacking pAB3,S/T sensitive, T6SS active, hcp mutant | This study (21) |

| Ab17978T6+∆tssM | Ab17978 lacking pAB3, S/T sensitive, T6SS active, tssM mutant | This study (21) |

| Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS) | Spontaneous rifampicin-resistant mutant of Ab17978T6+, harbors pBAVMCS for kanamycin resistance, used for conjugation study | This study |

| A. baumannii 1438 | Clinical isolate | This study |

| Ab1438T6– | Ab1438 containing plasmid, antibiotic resistant, T6SS inactive | This study |

| Ab1438T6+ | Ab1438 lacking plasmid, antibiotic sensitive, T6SS active | This study |

| A. baumannii ATCC 19606 | Type strain; wild type | ATCC |

| A. baylyi ADP1 | Wild type | (43) |

| V. cholerae V52 | hlyA−, hapA−, and rtxA− | (44) |

| V. cholerae V52vasK | vasK minus derivative of V52 | (44) |

| E. coli MG1655R | Rifampicin-resistant K-12 strain, bacterial prey for Ab04T6– for surviving cell number enumeration | (44) |

| E. coli Ec01 | Clinical isolate, from patient who was also infected with A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae | (26) |

| K. pneumoniae Kp01 | Clinical isolate, from patient who was also infected with A. baumannii and E. coli | (26) |

| E. coli DH5α | General cloning and plasmid propagation | Invitrogen |

| E. coli TG1 | Killing assay prey (with pBAV1K-T5-gfp) | Stratagene |

| E. coli Top10 | General cloning and plasmid propagation, killing assay prey (with pHC60) | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAV1K-t5-gfp | GFP expressing plasmid, used for killing assays | (45) |

| pEXT20 | General cloning plasmid; AmpR | (46) |

| pBAVMCS | pBAV1K-t5-gfp with GFP gene removed, E. coli–Acinetobacter shuttle plasmid; KanR | (47) |

| pBAVMCS-tet | pBAVMCS with tetracycline gene from pWH1266 inserted at SacI site | This study |

| pWH1266 | Expression plasmid, E. coli–Acinetobacter shuttle plasmid; Tetr | (48) |

| pTetR1-1 | tetR1 (locus tag: ACX61_19615) in pEXT20 | This study |

| pTetR1-2 | tetR1 (locus tag: ACX61_19615) in pBAVMCS | This study |

| pTetR1-3 | tetR1 (locus tag: ACX61_19615) in pWH1266 | This study |

| pTetR2-1 | tetR2 (locus tag: ACX61_19655) in pEXT20 | This study |

| pTetR2-2 | tetR2 (locus tag: ACX61_19655) in pBAVMCS | This study |

| pTetR2-3 | tetR2 (locus tag: ACX61_19655) in pBAVMCS-tet | This study |

| pHNS-1 | hns (locus tag: ACX61_19730) in pEXT20 | This study |

| pHNS-2 | hns (locus tag: ACX61_19730) in pWH1266 | This study |

Table S3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence, 5′–3′ |

| Node_182F | TTACAACAAGTATCTGTAGGTCCTGACC |

| Node_182R | AAGTGTCTGAATGTCTATCAATGCC |

| T6SSF | AATGTTGTACAGCAAGTTGATCC |

| T6SSR | AATTGCTTGTGAACTATCTTCTGG |

| H-nsFwdBamHI | AAAGGATCCTATACTCAGATTATTAGTGATCC |

| H-nsRevSalI6His | TATGTCGACTTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGTTTAATCAGGAATTCACTCAGC |

| H-nsFwdPstI | AAACTGCAGTATACTCAGATTATTAGTGATCC |

| H-nsRevPstI6His | TATCTGCAGTTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGTTTAATCAGGAATTCACTCAGC |

| pEXTMCSFwdPstI | ATATCTGCAGCAGGTCGTAAATCACTGCATAATTCG |

| TetR18-FwdBamHI | ATATGGATCCATGACTAAAGTTATTTCAAAAAGAAAAACC |

| TetR18-RevPstI | ATTACTGCAGTTAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGAGCCTCAAATGTCTGAATTAGACTC |

| TetR22-FwdEcoRI | AATAGAATTCATGACAAATAAAGCTTCACAGCCTAG |

| TetR22-RevPstI6His | ATAACTGCAGTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGAAATTGCTCACCATATAAACTTTCAATATC |

| rpoB-1441F | GAGCGTGCTGTTAAAGAGCG |

| rpoB-2095R | CTGCCTGACGTTGCATGT |

SI Materials and Methods

Strains and Hcp Secretion Assays.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table S2. Strains were routinely grown in LB medium at 37 °C with shaking. The antibiotics ampicillin (50 µg⋅mL−1), kanamycin (50 µg⋅mL−1), tetracycline (5 µg⋅mL−1), rifampicin (100 µg⋅mL−1), gentamicin (15 µg⋅mL−1), and S/T (30/5 μg⋅mL−1) were added when necessary. Hcp-ELISAs were performed as previously described (21). Briefly, individual colonies of a given A. baumannii strain struck out on an agar plate were used to inoculate 96-well plates filled with growth medium. After overnight growth, plates were centrifuged and 75 µL of supernatants were transferred into high-binding ELISA 96-well plates containing 25 µL binding buffer and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The plates were then washed with PBS, blocked with a solution of 5% (wt/vol) skim milk, and then probed with 2.5% (wt/vol) skim milk–phosphate-buffered saline Tween-20 solution containing a 1:7,500 dilution of an anti-Hcp antibody. Following washes, HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Bio-Rad) was added at a 1:5,000 dilution to the plates. After another set of washes with PBST, 100 µL 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Cell Signaling Technologies) was added to the wells, and plates were allowed to develop for ∼5–10 min and then photographed.

T6+ strains (Ab04T6+, Ab17978T6+, Ab1438T6+) were isolated by Hcp-ELISA. When a well giving rise to a T6+ signal (i.e., blue color after ELISA) was identified, the original 96-well growth plate (the source of supernatant sample) was used to reisolate the cells. These cells were plated on LB agar, and subsequent rounds of Hcp-ELISAs were performed using freshly isolated individual colonies to confirm the T6+ phenotype. Further, the final T6+ colonies were tested for antibiotic resistances; Ab04T6+ and Ab1438T6+ were frequently tested for gentamicin (15 µg⋅mL−1) and tetracycline (5 µg⋅ml−1) sensitivity, and Ab17978T6+ was tested for sensitivity to the combination of S/T (30 µg⋅mL−1/6 µg⋅mL−1). Similarly, all T6– strains were tested for resistance to the above antibiotics. Western blots to confirm Hcp secretion phenotype were performed on whole cells and supernatants as described (21).

Bacterial Killing Assays.

Competition assays for Ab04T6–/T6+ were performed using either E. coli MG1655R or E. coli pBAV1K-t5-gfp as prey. The former strain was used to produce the serial dilution image shown in Fig. 1C and the latter for the GFP image. Assays were set up using overnight cultures that were normalized to an OD600 of 1 and done in triplicate. Strains grown with antibiotics were first washed before resuspension. A. baumannii and E. coli were mixed at a 1:1 ratio, and 5 μL was spotted on a dry LB agar plate. After 4 h, the spot was either cut out and resuspended in 1 mL liquid LB and 10 µL serial dilutions plated on rifampicin (100 µg⋅mL−1) to select for E. coli (when MG1655R was prey), or the plates were imaged directly on a FujiFilm FLA-5000 imaging system (Fuji Photo Film Co.) using the 473 nm SHG (second-harmonic generation) blue laser and LPB filter, with images acquired using a voltage between 300 and 400 (when E. coli containing pBAV1K-t5-gfp was prey). Representative images were used for figures. Controls consist of the E. coli prey incubated with a nonresistant or non–GFP-expressing E. coli parental strain.

For killing assays using the clinical Ec01 and Kp01 strains as prey, a spontaneous rifampicin-resistant mutant of Ec01 was obtained by plating an overnight culture on rifampicin (100 µg⋅mL−1). Kp01 was naturally rifampicin resistant. The Ec01 parental strain and a rifampicin-sensitive laboratory strain of K. pneumoniae were used as controls, and the killing assay was performed as for E. coli MG1655R, with the exception that the killing assay with K. pneumoniae as prey was done at a predator-to-prey ratio of 10:1 to clearly illustrate the killing phenotype of Ab04T6+. Subsequent killing assays shown in Figs. 2 and 4 and Fig. S3 were performed using E. coli pBAV1K-t5-gfp as prey and done as described above, with representative images shown. The assays shown in Figs. S4 and S5 were performed by using inherent antibiotic resistance differences between strains.

Disk Diffusion Assays.

Antibiotic resistance profiles were determined by disk diffusion. Overnight cultures were resuspended to OD 1in fresh media, 300 μL was plated onto LB agar, and discs were overlaid. After overnight incubation, plate images were acquired using a Molecular Imager Gel Doc XR system (Bio-Rad), and the provided software was used to measure inhibition zone diameter. All experiments were done in triplicate, and data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests. Antibiotics tested were amikacin (AK), ampicillin (AMP), aztreonam (ATM), chloramphenicol (C), ceftazidime (CAZ), ciprofloxacin (CIP), gentamicin (CN), erythromicin (E), imipenem (IMP), kanamycin (K), streptomycin (S), spectinomycin (SPT), S/T (SXT), tetracycline (TE), tobramycin (TOB), piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP), and T.

Genome Sequencing.

The DNA libraries for genomic DNA extracted from Ab04T6–, Ab04T6+, Ab17978T6–, and Ab17978T6+ (DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen) were prepared following the Pacific Biosciences 20 kb Template Preparation Using BluePippin Size-Selection System protocol. We sheared 7.5 µg of high-molecular-weight genomic DNA (final volume of 100 µL) using the Covaris g-TUBES (Covaris Inc.) at 4,500 rpm (1,900 × g) for 60 s on each side on an Eppendorf centrifuge 5424 (Eppendorf). The sheared DNA was size selected on a BluePippin system (Sage Science Inc.) using a cutoff range of 7 kb to 50 kb. The DNA damage repair, end repair, and SMRTbell ligation steps were performed as described in the template preparation protocol with the SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 reagents (Pacific Biosciences). The sequencing primer was annealed at a final concentration of 0.8333 nM, and the P4 polymerase was bound at 0.500 nM. The libraries were sequenced on a PacBio RSII instrument at a loading concentration (on-plate) of 80 pM using the MagBead loading protocol, DNA sequencing kit 2.0, SMRT cells v3, and 3-h movies. Sequencing was performed at the McGill University and Genome Quebec Innovation Center. Illumina sequencing was carried out at the McMaster Genomics Facility, and DNA libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT kit (Illumina) as per the manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq with 2× 250 bp paired-end reads. Fold coverage ranged from ∼150–205×, and initially assembly was carried out using SPAdes (40).

Identification of Other Strains Harboring Plasmids.

We screened our Acinetobacter strain library (∼15 isolates) using primer pairs Node_182F/Node_182R (Table S3) to identify other strains carrying plasmids similar to pAB04-1/pAB3. These primers target a conserved region on the plasmid. We bioinformatically identified other strains by BLAST, using the full pAB04-1/pAB3 plasmids as the query against both the nucleotide collection (nr) database and the whole genome shotgun (wgs) database.

Recombinant Plasmid Construction.

All primers are listed in Table S3. The hns gene was amplified from Ab04T6– by PCR with primers H-nsFwdBamHI and H-nsRevSalI6His and then cloned into pEXT20 using BamHI and SalI cut sites to produce pHNS1. hns was then reisolated and amplified by PCR using primers H-nsFwdPstI and H-nsRevPstI6His and inserted into pWH1266 by PstI to make pHNS2.

The genes encoding tetR1 and tetR2 were PCR amplified from Ab04T6– by PCR with primers TetR18-FwdBamHI, TetR18-RevPstI, TetR22-FwdEcoRI, and TetR22-RevPstI and then cloned into pEXT20 by BamHI/PstI and EcoRI/PstI (respectively) to construct pTetR1-1 and pTetR2-1. pTetR1-2 was constructed by subcloning tetR1 from pTetR1-1 into pBAVMCS using BamHI/PstI. pTetR1-3 was similarly constructed by isolation of tetR1 from pTetR1-1 with EcoRI/PstI and cloning into pWH1266. pTetR2-2 was constructed by PCR amplification of tetR2 with the pEXT20 promoter of pTetR2-1 using primers pEXTMCSFwdPstI and TetR22-RevPstI and cloning into the PstI site of pBAVMCS. The tetracycline resistance gene from pWH1266 was inserted into pTetR2-2 using SacI to construct pTetR2-3.

Plasmids were sequenced and transformed into strains by electroporation, and gene expression was confirmed by Western blot. For testing the effect of recombinant protein expression on Hcp expression/secretion, Ab04T6+ was transformed with pHNS-2, pTetR1-3, and pTetR2-3 and their respective empty vectors. Ab1438T6+, Ab17978T6+, and A. baumannii ATCC 19606 were transformed with pTetR1-2 and pTetR2-2 or empty pBAVMCS. A. baylyi ADP1 was transformed with pTetR1-3, pTetR2-2, or their respective empty vectors, whereas V. cholerae V52 was transformed with pTetR1-1, pTetR2-1, and pEXT20 empty vector.

Conjugation Experiments.

For conjugation experiments, Ab17978T6– was used as the donor and a modified strain of Ab17978T6+ was used as the recipient. A spontaneous rifampicin-resistant mutant of Ab17978T6+ was isolated, into which pBAVMCS (providing kanamycin resistance) was introduced by electroporation, generating Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS). Overnight cultures of Ab17978T6–, grown in S/T (to ensure plasmid maintenance), and Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS), grown in rifampicin (100 µg⋅mL−1) and kanamycin, were pelleted, washed three times in fresh media, and resuspended at an OD600 of 1. The cultures were mixed at a 1:1 ratio, and 25 µL was spotted onto an LB agar plate. After overnight incubation, the spots were harvested, resuspended in liquid LB, and plated onto media containing S/T and kanamycin. Colonies were only obtained from experiments where both strains were mixed together. Colonies were then replica plated onto several different antibiotic-containing media to ensure obtained colonies were indeed Ab17978T6+ (RifR; pBAVMCS), which obtained pAB3 plasmid. Growth on rifampicin, PCR for presence of plasmid with primers Node_182F and Node_182R, as well as sequencing of the rpoB gene with primers rpoB-1441F and rpoB-2095R (41) confirmed that all colonies tested were true transconjugants. Hcp expression and secretion was used as a final confirmation of pAB3 mobilization.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory of M. Pallen, especially J. Chan, as well as M. Surette for bioinformatic assistance, comments, and suggestions. We thank K. Rajakumar for discussions on A. baumannii genetics and K. Dewar and J. Wasserscheid for assistance with PacBio data. We thank M. Joffe and Alberta Health Services for providing bacterial isolates. This work was supported by funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (to M.F.F.). M.F.F was a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator, B.S.W is the recipient of NSERC Postgraduate Scholarship-Doctoral and Alberta Innovates - Technology Futures awards, and J.N.I was supported by an Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions/NSERC studentship award.

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. CP012004–CP012008).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1502966112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Boucher HW, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: No ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(1):1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sievert DM, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Team and Participating NHSN Facilities Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: Summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(1):1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valencia R, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of infection with pan-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a tertiary care university hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(3):257–263. doi: 10.1086/595977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maragakis LL, Tucker MG, Miller RG, Carroll KC, Perl TM. Incidence and prevalence of multidrug-resistant acinetobacter using targeted active surveillance cultures. JAMA. 2008;299(21):2513–2514. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hibbing ME, Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Peterson SB. Bacterial competition: Surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(1):15–25. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mougous JD, et al. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science. 2006;312(5779):1526–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.1128393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pukatzki S, et al. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(5):1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer F, Fichant G, Berthod J, Vandenbrouck Y, Attree I. Dissecting the bacterial type VI secretion system by a genome wide in silico analysis: What can be learned from available microbial genomic resources? BMC Genomics. 2009;10:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hood RD, et al. A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(1):25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basler M, Pilhofer M, Henderson GP, Jensen GJ, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion requires a dynamic contractile phage tail-like structure. Nature. 2012;483(7388):182–186. doi: 10.1038/nature10846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell AB, et al. Type VI secretion delivers bacteriolytic effectors to target cells. Nature. 2011;475(7356):343–347. doi: 10.1038/nature10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bingle LE, Bailey CM, Pallen MJ. Type VI secretion: A beginner’s guide. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cascales E. The type VI secretion toolkit. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(8):735–741. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pukatzki S, McAuley SB, Miyata ST. The type VI secretion system: Translocation of effectors and effector-domains. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basler M, Mekalanos JJ. Type 6 secretion dynamics within and between bacterial cells. Science. 2012;337(6096):815. doi: 10.1126/science.1222901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basler M, Ho BT, Mekalanos JJ. Tit-for-tat: Type VI secretion system counterattack during bacterial cell-cell interactions. Cell. 2013;152(4):884–894. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho BT, Basler M, Mekalanos JJ. Type 6 secretion system-mediated immunity to type 4 secretion system-mediated gene transfer. Science. 2013;342(6155):250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.1243745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernard CS, Brunet YR, Gueguen E, Cascales E. Nooks and crannies in type VI secretion regulation. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(15):3850–3860. doi: 10.1128/JB.00370-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverman JM, Brunet YR, Cascales E, Mougous JD. Structure and regulation of the type VI secretion system. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:453–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Berardinis V, et al. A complete collection of single-gene deletion mutants of Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:174. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber BS, et al. Genomic and functional analysis of the type VI secretion system in Acinetobacter. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carruthers MD, Nicholson PA, Tracy EN, Munson RS., Jr Acinetobacter baumannii utilizes a type VI secretion system for bacterial competition. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shneider MM, et al. PAAR-repeat proteins sharpen and diversify the type VI secretion system spike. Nature. 2013;500(7462):350–353. doi: 10.1038/nature12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carruthers MD, et al. Draft genome sequence of the clinical isolate Acinetobacter nosocomialis strain M2. Genome Announc. 2013;1(6):e00906-13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00906-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry R, et al. Colistin-resistant, lipopolysaccharide-deficient Acinetobacter baumannii responds to lipopolysaccharide loss through increased expression of genes involved in the synthesis and transport of lipoproteins, phospholipids, and poly-β-1,6-N-acetylglucosamine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):59–69. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05191-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed-Bentley J, et al. Gram-negative bacteria that produce carbapenemases causing death attributed to recent foreign hospitalization. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(7):3085–3091. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00297-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyata ST, Unterweger D, Rudko SP, Pukatzki S. Dual expression profile of type VI secretion system immunity genes protects pandemic Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(12):e1003752. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eid J, et al. Real-time DNA sequencing from single polymerase molecules. Science. 2009;323(5910):133–138. doi: 10.1126/science.1162986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith MG, et al. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21(5):601–614. doi: 10.1101/gad.1510307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang FC, Rimsky S. New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11(2):113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salomon D, Klimko JA, Orth K. H-NS regulates the Vibrio parahaemolyticus type VI secretion system 1. Microbiology. 2014;160(Pt 9):1867–1873. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.080028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castang S, McManus HR, Turner KH, Dove SL. H-NS family members function coordinately in an opportunistic pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(48):18947–18952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808215105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuthbertson L, Nodwell JR. The TetR family of regulators. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77(3):440–475. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00018-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishikawa T, Rompikuntal PK, Lindmark B, Milton DL, Wai SN. Quorum sensing regulation of the two hcp alleles in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright MS, et al. New insights into dissemination and variation of the health care-associated pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii from genomic analysis. MBio. 2014;5(1):e00963-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00963-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersson DI, Hughes D. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: Is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(4):260–271. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sturm A, et al. The cost of virulence: Retarded growth of Salmonella Typhimurium cells expressing type III secretion system 1. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(7):e1002143. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eijkelkamp BA, et al. H-NS plays a role in expression of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence features. Infect Immun. 2013;81(7):2574–2583. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00065-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hornsey M, et al. Whole-genome comparison of two Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a single patient, where resistance developed during tigecycline therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(7):1499–1503. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norton MD, Spilkia AJ, Godoy VG. Antibiotic resistance acquired through a DNA damage-inducible response in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol. 2013;195(6):1335–1345. doi: 10.1128/JB.02176-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piechaud M, Second L. [Studies of 26 strains of Moraxella Iwoffi] Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 1951;80(1):97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juni E. Interspecies transformation of Acinetobacter: Genetic evidence for a ubiquitous genus. J Bacteriol. 1972;112(2):917–931. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.2.917-931.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacIntyre DL, Miyata ST, Kitaoka M, Pukatzki S. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system displays antimicrobial properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(45):19520–19524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012931107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bryksin AV, Matsumura I. Rational design of a plasmid origin that replicates efficiently in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dykxhoorn DM, St Pierre R, Linn T. A set of compatible tac promoter expression vectors. Gene. 1996;177(1-2):133–136. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scott NE, et al. Diversity within the O-linked protein glycosylation systems of acinetobacter species. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(9):2354–2370. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.038315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunger M, Schmucker R, Kishan V, Hillen W. Analysis and nucleotide sequence of an origin of DNA replication in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and its use for Escherichia coli shuttle plasmids. Gene. 1990;87(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90494-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]