Significance

The light-driven generation of H2, the reductive side of water splitting, requires a light absorber or photosensitizer (PS) for electron-hole creation and photoinduced electron transfer. To increase the effectiveness of charge transfer chromophores as PSs, this report describes the attachment of a strongly absorbing organic dye (dipyrromethene-BF2, commonly known as Bodipy) to Pt diimine dithiolate charge transfer chromophores and examination of systems containing these dyads for the light-driven generation of H2. The use of these dyads increases system activity under green light irradiation (530 nm) relative to systems with either chromophore alone, validating such an approach in designing artificial photosynthetic systems. One dyad system exhibits both high activity and substantial durability (40,000 turnovers relative to PSs over 12 d).

Keywords: photochemistry, solar energy conversion, hydrogen, spectroscopy, synthesis

Abstract

New dyads consisting of a strongly absorbing Bodipy (dipyrromethene-BF2) dye and a platinum diimine dithiolate (PtN2S2) charge transfer (CT) chromophore have been synthesized and studied in the context of the light-driven generation of H2 from aqueous protons. In these dyads, the Bodipy dye is bonded directly to the benzenedithiolate ligand of the PtN2S2 CT chromophore. Each of the new dyads contains either a bipyridine (bpy) or phenanthroline (phen) diimine with an attached functional group that is used for binding directly to TiO2 nanoparticles, allowing rapid electron photoinjection into the semiconductor. The absorption spectra and cyclic voltammograms of the dyads show that the spectroscopic and electrochemical properties of the dyads are the sum of the individual chromophores (Bodipy and the PtN2S2 moieties), indicating little electronic coupling between them. Connection to TiO2 nanoparticles is carried out by sonication leading to in situ attachment to TiO2 without prior hydrolysis of the ester linking groups to acids. For H2 generation studies, the TiO2 particles are platinized (Pt-TiO2) so that the light absorber (the dyad), the electron conduit (TiO2), and the catalyst (attached colloidal Pt) are fully integrated. It is found that upon 530 nm irradiation in a H2O solution (pH 4) with ascorbic acid as an electron donor, the dyad linked to Pt-TiO2 via a phosphonate or carboxylate attachment shows excellent light-driven H2 production with substantial longevity, in which one particular dyad [4(bpyP)] exhibits the highest activity, generating ∼40,000 turnover numbers of H2 over 12 d (with respect to dye).

Water splitting into hydrogen and oxygen is the key energy-storing reaction of artificial photosynthesis (AP) and one of the most promising long-term strategies for carbon-free energy on a potentially global scale (1). As a redox reaction, water splitting has been studied primarily in terms of its two half-reactions, the reduction of aqueous protons to H2 and the oxidation of water to O2 (2–13). Whereas some of these studies date back more than 30 y (14–22), recent progress on each half-reaction has been notable, particularly with regard to catalyst development and mechanistic understanding of each transformation (6, 23–29). In this paper, we focus on efforts dealing with the light-driven generation of H2, which in its simplest form requires a light absorber or photosensitizer (PS) for electron-hole creation, a means or pathway for charge separation and electron transfer, an aqueous proton source, a catalyst for collecting electrons and protons and promoting their conversion to H2, and an ultimate source of electrons in the form of an electron donor.

Dating from the earliest work on the light-driven generation of H2, the photosensitizer has most often been a Ru(II) complex with 2,2′-bipyridine (bpy) and/or related heterocyclic ligands having a long-lived triplet metal-to-ligand charge transfer state (3MLCT) (5, 7, 30–33). Recent studies have included analogous Ir(III) d6 systems based on phenylpyridine (ppy) ligands in place of bpy (34). With charge transfer excited states, the sensitizers are poised for photoinduced electron transfer following photon absorption and intersystem crossing (ISC). Another set of charge-transfer chromophores that have been used in related systems is [Pt(terpyridyl)(arylacetylide)]+ complexes that also have 3MLCT states (35–37). Despite their success with photoinduced electron transfer, all of these charge transfer (CT) complexes have absorptions that are too weak for efficient photon capture with molar extinction coefficients (ε) of 7–15 × 103 M−1⋅cm−1, and the energies of their singlet absorbing states (1MLCT) are too high (typically >2.6 eV with λ < 490 nm) for effective use of the solar spectrum. More strongly absorbing organic dyes with ε of ∼105 M−1⋅cm−1 were also examined during early studies of the light-driven generation of H2. Whereas those with heavier halogen substituents such as Rose Bengal and Eosin Y were found to promote H2 formation because of facile ISC to long-lived 3ππ* states, they also exhibited poor photostability, decomposing within 3–5 h (38–41).

Platinum diimine dithiolate complexes (PtN2S2) such as 1 constitute another class of charge transfer chromophores that are solution luminescent and undergo electron transfer quenching of both oxidative and reductive types (42–48). The excited state energies of these complexes are significantly lower than those of the Ru(bpy), Ir(ppy), and Pt(terpyridyl) complexes mentioned above and have an excited state that has been described as having both MLCT and ligand-to-ligand charge transfer (LLCT) character. In complexes such as 1, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is of mixed character, being composed of substantial percentages of both Pt-based and dithiolate-based wavefunctions. As a consequence of the mixed character of the HOMO in PtN2S2, the excited states derived from HOMO to LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) excitation have been labeled mixed-metal ligand-to-ligand′ charge transfers (MMLL′CT). Based on these charge transfer states, two of the PtN2S2 complexes, including 1 with R = COOH, were examined as photosensitizers for H2 generation with TiO2 as the electron conduit and Pt islands on the TiO2 surface as the catalyst (49). The deprotonated carboxlyate groups of di(carboxy)bipyridine (dcbpy) served to link the PS to the platinized TiO2 (Pt-TiO2). The system produced hydrogen and proved to be stable for more than 70 h, using light of λ > 450 nm. However, activity of the system was low, based in part on the low absorptivity of the PtN2S2 chromophore and the small amount of the complex bound to TiO2.

To improve absorptivity of the PS in such H2 generating systems, an approach was initiated in which a strongly absorbing organic dye was linked directly to the PtN2S2 moiety for more efficient photon absorption and subsequent energy transfer to the CT chromophore. Such a strategy had been adopted by Ziessel through the synthesis of a bipyridine linked to a dipyrromethene-BF2 (Bodipy) dye similar to 2 and was examined for Ru complexes containing this ligand, resulting in sensitization of the lower-energy 3ππ* of the Bodipy part of the molecule (50). In a study by Lazarides et al. (51), the dye-CT dyad 3 that contained 2 and the dithiolate-linked Bodipy dyad 4 were synthesized and examined by absorption spectroscopy and transient absorption measurements to determine the potential success of photoinduced charge separation. In that study, it was determined that the absorption spectra of the two dyads are essentially the sum of each constituent chromophore and that the redox potentials of each component are virtually unaffected by bringing the two units together in a dyad. The measurements also showed that energy transfer from the 1ππ* state of the Bodipy moiety to the 1MMLL′CT state was energetically favorable and that for both 3 and 4, the dynamics progressed as shown in Scheme 1. Although the rates of both singlet energy transfer (SenT) and ISC for the two dyads were similar and proceeded in less than 1 ps, a significant difference was seen for the triplet energy transfer (TEnT) step with the time constant for 3 being 8 ps whereas that for 4 was 160 ps, indicating that for productive electron transfer to TiO2, the arrangement in 4 with Bodipy attached to the dithiolate was preferred.

Scheme 1.

Jablonski diagram of the Bodipy-PtN2S2 dyads showing the transitions between the different states (SEnT, singlet energy transfer; ISC, intersystem crossing; TEnT, triplet energy transfer).

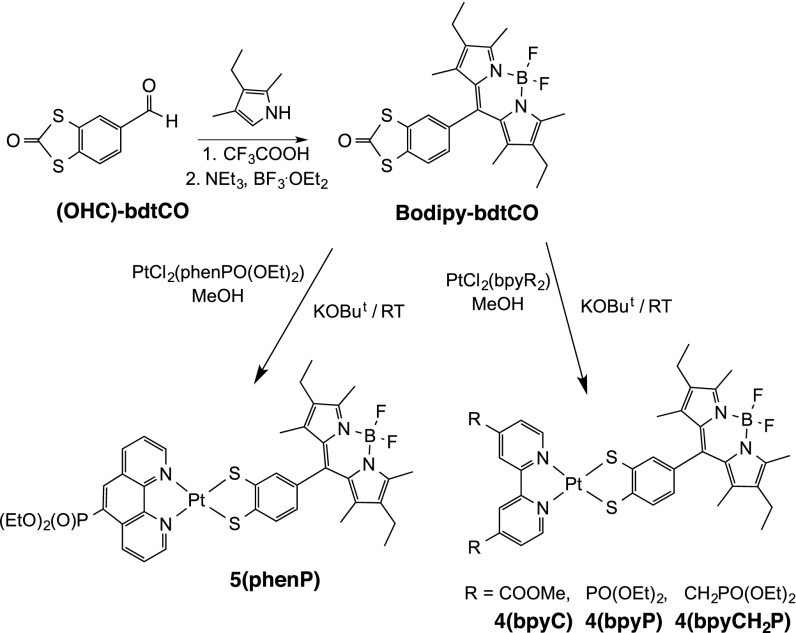

In this paper, the synthesis and characterization of dyads 4 with R = COOMe, P(O)(OEt)2, CH2(P(O)(OEt)2) and an analogous phenanthroline (phenP) derivative 5 are described, along with studies of their ability to promote light-driven production of H2 from aqueous protons in conjunction with Pt-TiO2 as both electron conduit and catalyst. The benefit of attaching the strongly absorbing bodipy chromophore to the charge transfer PtN2S2 complex is discussed.

Results and Discussion

Syntheses and Characterization.

PtCl2(diimine) complexes in which the diimine is a derivatized bpy or phen were prepared by the reaction of cis-Pt(DMSO)2Cl2 with the corresponding diimine and isolated as a precipitate from the reaction mixture. The particular diimines used were 4,4′-bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2,2′-bipyridine, 4,4′-bis(diethylphosphonyl)-2,2′-bipyridine, 4,4′-bis(diethylphosphonomethyl)-2,2′-bipyridine, and 5-diethylphosphonyl-1,10-phenanthroline. The subsequent reaction of the particular PtCl2(diimine) complex with 1,2-benzenedithiol (bdt) led to the corresponding derivative of 1. For simplicity, the diimines are denoted, respectively, as bpyC, bpyP, bpyCH2P, and phenP in complexes 1 and dyads 4.

The dithiolene ligand precursor that led to formation of dyad 4 with R=H [that is, 2-oxobenzo[d][1,3]dithiole-5-[1,3,5,7-tetramethyl-2,6-diethyl(4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene)] (Bodipy-bdtCO)] was prepared following the previously reported procedure involving the compound denoted as (OHC)-bdtCO (51). Dyads 4 with R = COOMe, P(O)(OEt)2, CH2(P(O)(OEt)2) were synthesized according to Scheme 2. The resultant dyads were characterized by elemental analyses, mass spectrometry, and 1H NMR spectroscopy (see Experimental section and SI Appendix for NMR spectra). In addition to the complexes containing the PtN2S2 charge transfer chromophore, compound 6 was made by carrying out the Bodipy synthesis using 3-ethyl-2,4-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole and diethyl(4-formylphenyl)phosphonate.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the derivatives of dyads 4 and 5.

UV-Vis Absorption Studies.

The absorption spectra for Pt complexes 1 with R = COOMe, P(O)(OEt)2, CH2(P(O)(OEt)2) and the corresponding dyads 4 in CH3CN at room temperature are presented in Figs. 1 and 2, and relevant absorption maxima are summarized in Table 1. Solutions of dyads 4 and the charge transfer chromophores 1 exhibit strong absorptions around 300 nm due to ππ* transitions involving the polypyridine ligands (bpy or phen) (see Figs. 1 and 2, respectively). The spectra of the dyads exhibit the strong absorption band of the Bodipy chromophore at 530 nm that shows little change as R is varied and agrees with that of 6, consistent with electronic separation of the two chromophores in the dyads. Another prominent feature in the visible spectra for the derivatives of 1 and 4 corresponds to the band for the 1MMLL′CT absorption in the 500- to 700-nm region. The absorption bands are broad and shift significantly with the bpy substituent, moving from 525 nm with bpy R = H (51) to 613 nm and 594 nm for R = COOMe, P(O)(OEt)2, respectively. The change is consistent with the LUMO for the 1MMLL′CT absorption being bpy based and the COOMe and P(O)(OEt)2 substituents being strongly electron withdrawing. For 1 with R = CH2(P(O)(OEt)2 and for the phenanthroline dyad 5, there is little observable effect of the electron withdrawing ability of the phosphonate ester group (52).

Fig. 1.

UV-vis absorption spectra of dyads 4(bpyC) (blue), 4(bpyP) (red), 4(bpyCH2P) (black), and 5(phenP) (green), as well as the Bodipyphosphonate ester 6 (pink) in acetonitrile. Spectra have been normalized to give a maximum Bodipy absorbance of 1.

Fig. 2.

UV-vis absorption spectra of PtN2S2 complexes 1(bpyC) (blue), 1(bpyP) (red), 1(bpyCH2P) (black), and 1(phenP) (green) in acetonitrile. Spectra have been scaled for the same maximum absorbance of the MMLL′CT absorption bands at ∼600 nm.

Table 1.

Absorption maxima for PtN2S2 complexes and associated Bodipy dyads 4 and 5 in CH3CN at RT

| Sensitizer | Absorption λmax, nm (molar absorptivity ε, M−1⋅cm−1) |

| 1(bpy) | 307 (27,200), 542 (6,890) |

| 1(bpyC) | 315 (12,500), 326 (14,500), 620 (7,100) |

| 1(bpyP) | 317 (28,400), 610 (9,700) |

| 1(bpyCH2P) | 303 (32,100), 546 (8,000) |

| 1(phenP) | 318 (6,900), 439 (3,900), 552 (8,600) |

| 4(bpyC) | 326 (26,500), 383 (13,600), 523(68,400), 613 (8,900) |

| 4(bpyP) | 306 (29,200), 317 (33,000), 370 (11,900), 522 (71,600), 594 (10,700) |

| 4(bpyCH2P) | 303 (32,800), 373 (9,200), 522 (63,900), 537 (8,400) |

| 5(phenP) | 321 (12,000), 379 (9,600), 397 (9,900), 522 (75,500), 541 (9,600) |

| 6 | 379 (7,200), 397 (6,300), 523 (66,400) |

Crystal Structure Characterizations.

Single crystals of 1(bpyC) and 4(bpyP) were obtained by diffusion of diethyl ether into dichloromethane and acetonitrile solutions of the respective compounds. For the Bodipy dye with a phosphonate ester 6, crystals were obtained by layering hexane onto a dichloromethane solution of the dye. Each of these compounds was structurally characterized by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 3). Complete parameters for each structure determination are available in SI Appendix, a summary of crystallographic data is given in SI Appendix, Table S1, and key bond lengths and angles for 1(bpyC) and 4(bpyP) are presented in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Fig. 3.

(A–C) Molecular structures of 1(bpyC) (A), 4(bpyP) (B), and 6 (C). Thermal ellipsoids at the 50% probability level are shown. The hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. In 4(bpyP), the severely disordered ethyl groups of the PO(OEt)2 and a diethyl ether molecule of crystallization are omitted for clarity.

In the crystal structure of 1(bpyC), the geometry about the Pt(II) ion is essentially square planar with minor distortions caused by bite angle limitations of the chelating ligands and a very minor torsional deformation of 2.0° (the dihedral angle between the S1-Pt-S2 and N1-Pt-N2 planes). The observed Pt-S and Pt-N bond lengths are similar to those observed for other Pt(II) diimine dithiolate complexes (42–46, 49, 51). In the crystal structure of dyad 4(bpyP), the two essentially planar moieties, Bodipy and Pt(bdt)(bpy), which are covalently linked via the bdt ligand, have a dihedral angle of 74.6°, as measured between the dipyrromethene and bdt planes. As a consequence of the methyl substituents on the pyrrole rings, rotation about the C-C bond connecting the two chromophores is restricted. Severe disorder of ethyl groups of the two phosphonate ester substituents on bpy was observed, precluding a fully satisfactory refinement. The structure of Bodipy dye 6 is very similar to related Bodipy structures (53). The p-phenylene ring attached to the P(O)(OEt)2 ester makes a dihedral angle of 73° with the dipyrromethene-boron plane, making possible only very modest conjugation between the two moieties. The observed dihedral angle is very similar to that found in the structure of 4(bpyP) between the planar Bodipy and bdt rings.

Electrochemical Characterization of the Dyads.

All of the Bodipy-Pt(diimine)(dithiolate) dyads, as well as the corresponding component compounds, were studied by cyclic voltammetry and their electrochemical data are collected in Table 2. The two Bodipy compounds, Bodipy-bdt(CO) and 6, exhibit similar cyclic voltammetries (CVs) with a single reversible reduction at −1.58 V and −1.56 V and a single reversible oxidation at 0.66 V and 0.65 V, respectively (Fig. 4 A and B), that are attributable to the dye. A silver wire was used as the quasi-reference electrode and calibrated against ferrocene. All redox potentials are reported vs. the Fc/Fc+ couple that has a value of 0.40 V vs. SCE with SCE = 0.24 relative to NHE (50, 53–57). The cyclic voltammograms of the Pt(diimine)(bdt) complexes 1(bpyC) and 1(bpyP) each exhibit two reversible reductions in the ranges between −1.39 V to −1.41 V and −1.9 V to −2.03 V, as well as two irreversible oxidations in the range 0.04–0.54 V (Fig. 4 C and D), whereas for 1(bpyCH2P) and for 1(phenP), only one reversible reduction at more cathodic values (between −1.62 V and −1.74 V), as well as two irreversible oxidations, are seen in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. The less negative first reduction potential and observation of a second reduction for 1(bpyC) and 1(bpyP) are a consequence of the ester electron withdrawing abilities on the energy of the π* LUMO that serves as the acceptor orbital upon reduction. Both –COOMe and –P(O)(OEt)2 are strongly electron withdrawing groups, whereas in complexes with bpyCH2P and phenP, the effect is essentially muted. These observations are consistent with the spectroscopic results discussed above regarding the position of the 1MMLL′CT absorption.

Table 2.

Summary of oxidation and reduction potentials (V vs. Fc/Fc+)

| E1/2*/V (ΔEp/mV)†: Epc/V (irrev) | E1/2*/V (ΔEp /mV)†: Epa/V (irrev) | |

| 1(bpyC) | −1.90 (73); −1.39 (65) | +0.17 (irrev); +0.54 (irrev) |

| 1(bpyP) | −2.03 (71); −1.41 (80) | +0.13 (irrev); +0.54 (irrev) |

| 1(bpyCH2P) | −1.74 (76) | +0.04 (irrev); +0.31 (irrev) |

| 1(phenP) | −1.62 (irrev) | +0.06 (irrev); +0.32 (irrev) |

| Bodipy-bdtCO | −1.58 (94) | +0.66 (81) |

| 6 | −1.56 (74) | +0.65 (76) |

| 4(bpyC) | −1.90 (81); −1.66 (72); −1.31 (62) | +0.36 (irrev); 0.69 (irrev) |

| 4(bpyP) | −1.98 (106); −1.67 (75); −1.32 (81) | +0.42 (irrev); +0.72 (irrev) |

| 4(bpyCH2P)‡ | −1.85 (irrev) | +0.36 (irrev); 0.72 (irrev) |

| 5(phenP)‡ | −1.74 (irrev); −1.85 (irrev) | +0.35 (irrev); 0.73 (irrev) |

All measurements were at room temperature in dry CH3CN at ∼1 × 10−3 M concentration in solutions containing 0.1 M (TBA)PF6 as supporting electrolyte. A silver wire quasi-reference electrode was used and calibrated vs. Fc/Fc+ couple [0.40 V vs. SCE (58) with SCE vs. NHE = 0.24 V]. irrev, irreversible.

E1/2 = (Epa + Epc)/2; Epa and Epc are anodic and cathodic peak potentials, respectively.

ΔEp= (Epa – Epc). ΔEp = 80 mV for Fc/Fc+ couple.

4(bpyCH2P) and 5(phenP) were measured in dry CH2Cl2.

Fig. 4.

(A–F) Cyclic voltammograms of (A) 6, (B) Bodipy-bdtCO, (C) 1(bpyC), (D) 1(bpyP), (E) 4(bpyC), and (F) 4(bpyP) were measured in 0.1 M TBAPF6/dry CH3CN solution. Potentials are referenced to Fc/Fc+.

The cyclic voltammograms of all of dyads 4, shown in Fig. 4, correspond to a sum of the CVs of individual Pt(bdt)(bpy) and Bodipy components. For 4(bpyC) and 4(bpyP), three reversible reduction couples between −1.31 V and −1.98 V are observed, as shown in Fig. 4 E and F, corresponding to the one Bodipy and two PtN2S2 reductions. For the dyad 4(bpyCH2P), only one quasi-reversible reduction couple around −1.85 V is found (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C) and for 5(phenP), evidence for two reduction waves that are quasi-reversible at best is seen. For all of the dyads, one reversible anodic wave and one irreversible anodic wave are seen, corresponding to Bodipy and PtN2S2 oxidations, respectively.

Attachment of Dyads to TiO2.

The main objective of the present study was to determine whether photofunctional dyads such as 4 were efficient when attached to TiO2 for electron photoinjection into the semiconductor. The most common method for attachment of light absorbers to TiO2 nanoparticles is through various anchoring groups such as carboxylate, phosphonate, sulfonate, salicylate, acetylacetonate, catecholate, and hydroxamate (59–64). In the present study, with phosphonate esters and carboxylate esters as diimine substituents on PtN2S2 chromphores and dyads, attempts to hydrolyze the esters prior to TiO2 attachment proved problematic because of poor stability of the PtN2S2 moiety under the hydrolysis conditions. However, in light of an earlier observation of partial hydrolysis of a phosphonate ester of a rhodamine derivative when examined with TiO2 (65), the idea of using in situ hydrolysis for attachment was attempted with complexes 1 and dyads 4, 5, and 6 in the presence of TiO2.

An effective procedure was found that involved sonication of a slurry of platinized TiO2 (Pt-TiO2) in an acetonitrile solution of the PtN2S2 complex or dyad containing the phosphonate ester, followed by isolation of the solid, which was then washed with CH3CN twice and dried under vacuum. Higher attachment was obtained with 20 min sonication. A comparison of the UV-vis spectra of dyes in CH3CN before and after sonication and removal of Pt-TiO2 showed a substantial decrease in the intensities of the MMLL′CT and/or Bodipy absorptions, which gave an approximate percentage of PtN2S2 complex or dyad attached to the surface of TiO2. With no anchoring group present as in compounds 1(bpy) and 4(bpy), UV-vis spectra revealed a decrease of 11–16% of the characteristic bands between the initial and final solutions, indicating little if any binding to Pt-TiO2 (Table 3 and SI Appendix, Figs. S14 and S19). For complexes having a single anchoring group such as 1(phenP) and 5(phenP), the decreases were much more notable, corresponding to binding of ∼70%. For the systems having two phosphonate ester substituents as possible anchoring groups such as in PtN2S2 complexes 1(bpyP), 1(bpyCH2P) and dyads 4(bpyP), 4(bpyCH2P), the degree of attachment increased significantly, corresponding to 82–99% attachment. The results are clearly consistent with binding of the PtN2S2 complexes and dyads occurring via the anchoring groups, rather than simply through physisorption. Due to poor solubility in acetonitrile, the sonication procedure did not work initially with the carboxylate PtN2S2 complex 1(bpyC) and the corresponding dyad 4(bpyC). However, through the use of methylene chloride solutions (rather than acetonitrile), these systems also showed excellent attachment to Pt-TiO2 (87–89%).

Table 3.

Light-driven hydrogen production with different photosensitizers

| Complexes | Irradiation time, h | H2, mL | Attachment, % | H2 TON* | H2 TOF† |

| 1(bpy) | 60 | 1.0 | 16 | 2,100 | 114 |

| 1(bpyP) | 60 | 16.9 | 82 | 7,000 | 210 |

| 1(bpyCH2P) | 60 | 4.9 | 99 | 1,700 | 84 |

| 1(phenP) | 60 | 3.9 | 72 | 1,800 | 54 |

| 1(bpyC) | 60 | 4.1 | 89 | 1,600 | 84 |

| 4(bpy) | 60 | 2.3 | 11 | 7,100 | 361 |

| 4(bpyP) | 60 | 44.1 | 97 | 15,400 | 547 |

| 4(bpyCH2P) | 60 | 20.6 | 99 | 7,100 | 318 |

| 4(bpyC) | 60 | 11.7 | 87 | 4,600 | 185 |

| 5(phenP) | 60 | 7.3 | 70 | 3,500 | 171 |

| 6 | 60 | 1.6 | 36 | 1,500 | 57 |

| 4(bpyP) | 288 | 115.8 | 97 | 40,300 | — |

General conditions: for attachment, 20 mg of Pt-TiO2 and 2.5 mL of 50 µM solution of photosensitizer in CH3CN or CH2Cl2 were sonicated for 20 min; for H2 generation, 20 mg of dried Pt-TiO2 containing the attached photosensitizer was added to 5 mL of 0.5 M ascorbic acid in H2O at pH 4.0 and irradiated with 530 nm light.

Turnovers of H2 are given with respect to photosensitizer attached to Pt-TiO2.

The initial turnover frequency (TOF) of H2 is given per mole of photosensitizer per hour.

All of the attachment results are given in Table 3 and SI Appendix. Fig. 5 shows the corresponding spectra for dyad 4(bpyP) in CH3CN leading to attachment estimated at 97%. Fig. 6 provides results from diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of the dye-attached Pt-TiO2 powders showing the MMLL′CT absorption for the PtN2S2 complexes 1 and both the Bodipy and MMLL′CT absorptions for dyads 4 and 5. When linked to TiO2 in this manner, neither the complexes nor the dyads exhibited any evidence of dissociation from the nanoparticles when placed in water or aqueous/acetonitrile solvents.

Fig. 5.

UV-vis spectra of the solution of 4(bpyP) in CH3CN (2.5 mL, 50 μM) before (black line) and after (red line) sonication with Pt-TiO2 (20 mg), followed by Pt-TiO2 removal. Sample solutions were in 2-mm cuvettes.

Fig. 6.

(A) Diffuse reflectance of series 1 attached to Pt-TiO2. (B) Diffuse reflectance of series 4, as well as 5(phenP) and 6 attached to Pt-TiO2. Each spectrum has been baseline corrected with a blank of Pt-TiO2.

Light-Driven H2 Production.

In this study, all of the dyads and PtN2S2 complexes, as well as Bodipy dye 6, were attached to Pt-TiO2 in the manner described above and then examined for light-driven H2 generation in pH 4 water with ascorbic acid (AA) as the sacrificial electron donor under 530 nm irradiation. For each sample, system pressure was monitored in real time, and at the end of each irradiation period, gas from the headspace of each sample was examined for H2 content quantitatively, as previously described (26, 27, 66, 67). In Fig. 7, H2 production using various chromophores is shown, whereas in Table 3 the results in terms of turnover numbers (TONs) and initial turnover frequency of H2 with respect to photosensitizer attached to Pt-TiO2 are given.

Fig. 7.

(A) Hydrogen production using different chromophores. (B) H2 production using 1(bpyP) (black line), 4(bpyP) (cyan line), and 6 (orange line). Each sample contained 5 mL of 0.5 M ascorbic acid in H2O at pH 4.0 to which was added 20 mg of Pt-TiO2 with the photosensitizer attached as described in the text. Each sample was irradiated with 530 nm light.

Of the different light absorbers examined after 60 h, dyad 4(bpyP) exhibits the highest activity with a TON of 15,400, whereas systems with dyads 4(bpyCH2P), 4(bpyC), and 5(phenP) are less active (7,100, 4,600, and 3,500 TONs, respectively). In each case, the activity of the dyad was found to be two to four times greater than that of the corresponding PtN2S2 complex (SI Appendix, Figs. S25–S29), suggesting that the direct binding of Bodipy to the PtN2S2 chromophore increases the potential light harvesting of the latter’s CT excited state. The value of having the CT chromophore also present for photoinduced electron transfer into TiO2 and H2 generation was demonstrated when the Bodipy dye 6 was used as photosensitizer without the PtN2S2 chromophore present, leading to a greatly diminished TON compared with both dyad 4(bpyP) and complex 1(bpyP) (Fig. 7B). In an analysis of the activity between 1(bpyP) and 1(bpyCH2P) or between 4(bpyP) and 4(bpyCH2P), the methylene spacer negatively impacts system activity, presumably by decreasing the effectiveness of electron transfer through the additional −CH2− moiety for the latter. Finally, attachment of the photosensitizer (PtN2S2 complex or dyad) to TiO2 through a linker is revealed by the fact that when either complex 1(bpy) or dyad 4(bpy) with no anchoring group is used, significantly smaller amounts of H2 are obtained (Table 3).

To date, a variety of organic and inorganic chromophores have been used in conjunction with Pt-TiO2 as the catalyst. Of several Pt(II) complexes that have been used with triethanolamine (TEOA) as the sacrificial donor (SD), Pt(II) terpyridyl acetylide complexes were found to generate 115 TONs in 12 h (λ > 410 nm) (37). Systems containing Ru bipyridyl complexes with EDTA as SD were reported to generate over 500 TONs in 3 h (λ > 420 nm) (68). In another study using TEOA as SD, several iodinated boron-dipyrromethene (Bodipy) dyes were shown to generate H2, with one derivative promoting formation of 70 TONs of H2 in 2 h (λ > 420 nm) (69) and another yielding ∼100 TONs in 25 h (λ > 420 nm) (70). Illumination of a selenorhodamine dye with white-light light-emitting diodes (LEDs) using ascorbic acid as SD resulted in ∼300 TONs of H2 in 67 h (65). Two other systems were reported to have much higher activity in H2 production. The first (71) used Eosin Y (λ > 460 nm) with TEOA as SD and produced ∼10,000 TONs of H2 in 5 h, whereas the second (72) used Alizarin (λ > 420 nm) with TEOA as SD and yielded ∼10,000 TONs in 80 h. Earlier experiments performed here and elsewhere have found Eosin Y to be unstable upon reductive quenching, suggesting that if correct, these very active systems involve photoinduced electron transfer from the dye into the platinized TiO2. Direct comparison of the present results with these earlier reports is not possible because of differences in the conditions used such as relative concentrations of system components, pH, the nature of the sacrificial donor, the light source used and its intensity, and the solvent.

Fig. 8A shows photographs for essentially complete attachment of 4(bpyP) to the semiconductor surface. The powder of Pt-TiO2 changed from gray to pinkish whereas the purple stock solution of 4(bpyP) became colorless after 20 min of sonication. After 60 h of irradiation, the H2-generating solution is also shown in Fig. 8B. The yellow color of the solution is indicative of dehydroascorbic acid (the oxidation product), whereas the solid of Pt-TiO2 attached with 4(bpyP) retains the characteristic color shown in Fig. 8A. The durability of the 4(bpyP) system was further probed by the addition of more ascorbic acid as system activity appeared to decline after 4 d. The AA addition led to a resumption of activity that continued for another ∼5 d, and it was again repeated, generating ∼40,000 TONs over 12 d. The results are shown in Fig. 8C. The Bodipy-PtN2S2 photosensitizer thus appears to be stable under the irradiation conditions used.

Fig. 8.

(A) Photographs showing the color change in Pt-TiO2 before and after sonication, with the initial purple color of 4(bpyP) in CH3CN becoming almost colorless. (B) solid and solution color after 60 h of 530 nm irradiation with ascorbic acid present (the yellow color of the solution corresponds to dehydroascorbic acid). (C) H2 production over 12 d for 4(bpyP) (2.5 mL, 50 μM), AA (5 mL, 0.5 M, pH 4.0), 20 mg of Pt-TiO2, with λirrad 530 nm at 15 °C.

Conclusions

The new dyads reported here consisting of a Bodipy dye and a PtN2S2 CT chromophore have been prepared and studied in the context of light-driven generation of H2 from aqueous protons with ascorbic acid as the sacrificial electron donor. The dyads exhibit both spectroscopic and electrochemical properties characteristic of the individual components with little electronic coupling between them. Each of the dyads has a diimine-attached substituent for binding to TiO2. Connection of the dyads and their respective PtN2S2 complexes to platinized TiO2 is achieved by a sonication procedure, and the resultant assemblies have been examined for the light-driven reduction of protons to H2. Under 530 nm irradiation in pure aqueous solution, dyad 4(bpyP) is found to be most active with ca. 40,000 TONs based on the dyad over a period of 12 d. For all of the dyads, the activity was found to be two to four times greater than that of the corresponding PtN2S2 complex. When the Bodipy dye is used alone as the light absorber and linked to Pt-TiO2, only minimal yields of H2 are obtained upon 530 nm irradiation, indicating that photoinduced electron transfer does not readily occur from the dye alone. The value of attachment of the light absorber to Pt-TiO2 is also demonstrated by substantially reduced H2 generation when a Bodipy-PtN2S2 dyad without a linkage to the TiO2 surface is used. From these results, we conclude that light absorption by the organic dye enhances formation of the 3MMLL′CT state, from which electron transfer occurs, and that attachment of this dyad assembly to Pt-TiO2 increases the overall H2-generating ability of the system. The results thus indicate the viability of a two-component light absorber (one strongly absorbing for photon capture and energy transfer, and the other set for excited state charge transfer) for generating hydrogen in the reductive side of water splitting.

Experimental

Chemicals.

All reactions were conducted under N2 atmosphere. The compounds 2,2′-bipyridine-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid, potassium tetrachloroplatinate (K2PtCl4), and tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0) purchased from Aldrich and 4,4′-dibromo-2,2′-bipyridine purchased from TCI were used without further purification. All solvents were dried before use. Syntheses of the following were done using published procedures: 2-oxobenzo[d][1,3]dithiole-5-[1,3,5,7-tetramethyl-2,6-diethyl(4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene)] (bodipy-bdtCO) (51), 4,4′-bis(methoxycarbonyl)-2,2′-bipyridine (4,4′-dcbpy) (73), 4,4′-bis(diethylphosphonate)-2,2′-bipyridine (4,4’-(P(O)(OEt)2)bpy) (74), 4,4′-bis(diethylphosphonomethyl)-2,2′-bipyridine (4,4′-(CH2P(O)(OEt)2)bpy) (74), diethyl 1,10-phenanthrolin-5-ylphosphonate (5-(P(O)(OEt)2)Phen) (75), cis-Pt(DMSO)2Cl2 (76), PtCl2(4,4′-dcbpy) (77, 78), PtCl2(4,4′-(P(O)(OEt)2)bpy) (77, 78), Pt(4,4′-(P(O)(OMe)2)bpy)Cl2 (77, 78), PtCl2(5-(P(O)(OEt)2)Phen) (77, 78), PtCl2(4,4′-(CH2P(O)(OEt)2)bpy) (77, 78), [Pt(4,4′-dcbpy)(CH3CN)2](CF3SO3)2 (79), and diethyl (4-formylphenyl)phosphonate (80). All other chemical precursors and solvents were obtained from commercial sources and were used as received.

Characterization.

The 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400-MHz spectrometer and referenced to either a residual proton resonance of the deuterated solvent or tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. Elemental analyses were performed using a PerkinElmer 2400 Series II Analyzer. Mass spectrometry was performed on all compounds, using a Shimadzu LCMS and an LTQ VELOS Thermo LCMS (positive mode), respectively. CV measurements were performed with a CHI 680D potentiostat at room temperature under Ar, using a one-compartment cell with a glassy-carbon working electrode (3 mm diameter), a glassy-carbon auxiliary electrode (3 mm diameter), and an Ag wire quasi-reference electrode (QRE). For all measurements, tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate was used as the supporting electrolyte with ferrocene as an internal reference. UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Cary 60 UV-vis spectrophotometer, using a 1-cm or 2-mm path length quartz cuvette in CH3CN. Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy was performed using a Dip Probe Coupler (Agilent) and a VideoBarrelino (Harrick).

Syntheses.

1(bpy).

bdt (16 mg, 0.11 mmol) was added to a solution of potassium tert-butoxide (25 mg, 0.22 mmol) in 5 mL of CH3CN and the solution was stirred for 15 min. Under N2, the solution was added to Pt(4,4′-bpy)Cl2 (46 mg, 0.11 mmol) in 2 mL of CH2Cl2. The resultant solution was stirred at room temperature for 11 h, after which it was reduced to dryness. The solid product was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using CH3CN as eluant. The main blue band was collected, and the solvent was removed, affording the desired product as a purple crystalline solid. Yield: 30 mg (55%). 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 400 MHz): 9.11 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.66 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.40 (t, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.79 (t, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.22 (t, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.71 (t, 2H, dithiolate aromatic). Anal. Calcd for PtC16H12N2S2: C, 39.10; H, 2.46; N, 5.70. Found: C, 39.05; H, 2.38; N, 5.63.

1(bpyC).

Method A.

Pt(4,4′-dcbpy)Cl2 (59 mg, 0.11 mmol) was suspended in 10 mL of deaerated methanol and bdt (16 mg, 0.11 mmol) was added, followed by potassium tert-butoxide (25 mg, 0.22 mmol). The suspension gradually darkened, and a purple precipitate appeared. The suspension was further stirred at room temperature under an atmosphere of nitrogen for 48 h, and the solid was collected by filtration. The crude product was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using CH2Cl2/EtOAc (5:1) as eluant. The main purple band was collected, and the solvent was removed, affording the desired product as a purple crystalline solid. Yield: 17 mg (25%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): 9.34 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.55 (s, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.95 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.23 (s, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.69 (s, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 4.03 (s, 6H, CH3). EI-MS(m/z): 608 [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for PtC20H16N2O4S2: C, 39.54; H, 2.65; N, 4.61. Found: C, 39.02; H, 2.52; N, 4.49.

Method B.

A suspension of Pt(4,4′-dcbpy)Cl2 (54 mg, 0.10 mmol) and AgOTf (100 mg, 0.39 mmol) in 6 mL CH3CN was refluxed for 36 h. After cooling to room temperature (RT), the reaction mixture was filtered and the filtrate was reduced to dryness to give a red solid. The isolated material, [Pt(4,4′-dcbpy)(CH3CN)2](CF3SO3)2 was washed with acetone and diethyl ether and then dried in vacuo. Yield: 69.5 mg (82%). Potassium tert-butoxide (18 mg, 0.16 mmol) was added to a solution of bdt (11 mg, 0.08 mmol) in 2 mL of acetonitrile and stirred for 20 min under N2, after which the solution was added to a solution of [Pt(4,4′-dcbpy)(CH3CN)2](CF3SO3)2 (69.5 mg, 0.082 mmol) in 2 mL of acetonitrile, which became dark blue immediately. The mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and the solid was isolated by filtration. The crude product was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using pure CH2Cl2 as eluant. The main blue band was collected, and the solvent was removed, affording the desired product as a blue crystalline solid. Yield: 21 mg (43%). Characterization data match method A values.

1(bpyP).

Potassium tert-butoxide (25 mg, 0.22 mmol) was added to a solution of bdt (16 mg, 0.11 mmol) in 5 mL of acetonitrile. After stirring for 15 min under N2, the solution was added to a suspension of Pt(4,4′-(P(O)(OEt)2)bpy)Cl2 (76 mg, 0.11 mmol) in 1 mL of acetonitrile, which became dark blue immediately. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 11 h and the solid was isolated by filtration. The crude product was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using a gradient of CH3CN/CH2Cl2 (1:3–1:1) to afford the product as a blue solid. Yield: 72 mg (86%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): 9.42 (t, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.41 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.76 (dd, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.27 (d, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.70 (d, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 4.19 (m, 8H, CH2 of ethyl groups), 1.31 (t, 12 H, CH3 of ethyl groups). EI-MS(m/z): 764 [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C24H30N2O6P2PtS2: C, 37.75; H, 3.96; N, 3.67. Found: C, 37.23; H, 3.77; N, 3.61.

1(bpyCH2P).

A solution of bdt (27 mg, 0.19 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (45 mg, 0.40 mmol) in 15 mL methanol was added dropwise to a solution of Pt(4,4′-CH2P(O)(OEt)2bpy)Cl2 (137 mg, 0.19 mmol) in 15 mL of CH2Cl2. The mixture was stirred for 12 h and the solution was evaporated to give a purple solid. The crude product was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using CH3CN as eluant. The main purple band was collected, and the solvent was removed affording the product, which was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/hexane to give needle-like crystals. Yield: (98 mg, 65%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): 9.11 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.05 (s, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.43 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.32 (s, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.74 (s, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 4.12 (m, 8H, CH2 of ethyl groups), 3.23 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.17 (s, 2H, CH2), 1.31 (t, 12 H, CH3 of ethyl groups). EI-MS(m/z): 792 [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C26H34N2O6P2PtS2•H2O: C, 38.57; H, 4.48; N, 3.46. Found: C, 38.56; H, 4.28; N, 3.40.

1(phenP).

A solution of bdt (27 mg, 0.19 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (45 mg, 0.40 mmol) in 15 mL methanol was added dropwise to a solution of Pt(5-phen-P(O)(OEt)2)Cl2 (110 mg, 0.19 mmol) in 15 mL of CH2Cl2.The mixture was stirred for 8h and the solution was evaporated to give a purple solid. The crude product was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/hexane. The purple solid obtained was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using CH2Cl2/hexane (2:1) as the eluant. The main purple band was collected, and the solvent was removed affording the product, which was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/pentane to give a purple powder. Yield: (64 mg, 52%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): 9.52 (d, 1H, Phen aromatic), 9.28 (d, 1H, Phen aromatic), 9.17 (d, 1H, Phen aromatic), 8.64 (d, 1H, Phen aromatic), 8.47 (d, 1H, Phen aromatic), 7.79 (t, 2H, Phen aromatic), 7.21 (s, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.69 (s, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 4.35 (m, 4H, CH2 of ethyl groups), 1.38 (t, 6 H, CH3 of ethyl groups). EI-MS(m/z): 652 [M+H]+. Anal. Calcd for C22H21N2O3PPtS2: C, 40.55; H, 3.25; N, 4.30. Found: C, 41.74; H, 3.48; N, 4.08.

4(bpyC).

Pt(4,4′-dcbpy)Cl2 (30 mg, 0.055 mmol) was suspended in 5 mL of deaerated methanol and bodipy-bdtCO (26 mg, 0.055 mmol) was added, followed by potassium tert-butoxide (12 mg, 0.11 mmol). The suspension was stirred at room temperature under an atmosphere of nitrogen for 48 h. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using CH2Cl2/EtOAc (4:1) as eluant. The main purple band was collected, and the solvent was removed. The residue was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/ether to give the product as 18 mg (36%) of black needle-like crystals. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): 9.40 (dd, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.61 (s, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.06 (dd, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.45 (d, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 7.25 (s, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.74 (d, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 4.02 (s, 6H), 2.49 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 2.37 (q, 4H, CH2 of ethyl groups), 1.48 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 1.02 (t, 6H, CH3 of ethyl groups). EI-MS(m/z): 910 [M+H]+, 890 [M-F]+. Anal. Calcd for C37H37BF2N4O4PtS2•(C2H5)2O: C, 50.05; H, 4.82; N, 5.69. Found: C, 50.31; H, 4.55; N, 5.56.

4(bpyP).

The preparation of 4(bpy-P(O)(OEt)2) is similar to that of 4 (bpy-COOMe) except that Pt(4,4′-dcbpy)Cl2 is replaced by Pt(4,4′-(P(O)(OEt)2)bpy)Cl2. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using CH2Cl2/acetone (3:2) as eluant. The main purple band was collected, and the solvent was removed. The residue was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/ether to give the product as 14 mg (39%) of black needle-like crystals. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): 9.52 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.56 (d, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.88 (m, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.51 (d, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 7.27 (s, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.72 (d, dithiolate aromatic), 4.29 (m, 8H, CH2 of ethyl groups), 2.48 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 2.34 (q, 4H, CH2 of ethyl groups on bodipy), 1.42 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 1.40 (m, 12H, CH3 of ethyl groups), 1.00 (t, 6H, CH3 of ethyl groups on bodipy). EI-MS(m/z): 1,066 [M+H]+, 1,046 [M-F]+. Anal. Calcd for C41H51BF2N4O6PtS2•0.5CH2Cl2: C, 44.97; H, 4.73; N, 5.06. Found: C, 44.52; H, 4.53; N, 5.17.

4(bpyCH2P).

A solution of bodipy-bdtCO (71 mg, 0.15 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (34 mg, 0.30 mmol) in 10 mL methanol was added dropwise to a solution of Pt(4,4′-(CH2P(O)(OEt)2)bpy)Cl2 (108 mg, 0.15 mmol) in 25 mL of CH2Cl2. The mixture was stirred for 35 h and the solution was evaporated to give a solid. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using CH2Cl2/hexane (2.5:1) as eluant. The main purple band was collected, and the solvent was removed, affording the product as a purple powder. Yield: (134 mg, 82%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): 9.20 (dd, 2H, bpy aromatic), 8.11 (s, 2H, bpy aromatic), 7.47 (m, 3H, 2H of bpy aromatic and 1H of dithiolate aromatic), 7.22 (s, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.68 (d, 2H, dithiolate aromatic), 4.12 (m, 8H, CH2 of ethyl groups), 3.29 (dd, 4H, CH2 on bpy), 2.48 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 2.33 (q, 4H, CH2 of ethyl groups on bodipy), 1.43 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 1.31 (m, 12H, CH3 of ethyl groups), 1.02 (t, 12 H, CH3 of ethyl groups on bodipy). EI-MS(m/z): 1,094 [M+H]+, 1,074 [M-F]+. Anal. Calcd for C43H55N4O6P2PtS2: C, 47.21; H, 5.07; N, 5.12. Found: C, 47.07; H, 5.11; N, 5.03.

5(phenP).

A solution of bodipy-bdtCO (71 mg, 0.15 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (34 mg, 0.30 mmol) in 10 mL methanol was added dropwise to a solution of PtCl2(5-(P(O)(OEt)2)Phen) (87 mg, 0.15 mmol) in 25 mL of CH2Cl2.The mixture was stirred for 30 h and the solution was evaporated to give a solid. The crude product was recrystallized by CH2Cl2/pentane and the purple solid obtained was purified by column chromatography on silica gel, using CH2Cl2/hexane (2.5:1) as eluant. The main purple band was collected, and the solvent was removed, affording the product. Yield: (102 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): 9.65 (m, 2H, Phen aromatic), 9.23 (t, 1H, Phen aromatic), 8.77 (m, 2H, Phen aromatic), 7.97 (m, 2H, Phen aromatic), 7.52 (d, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 7.27 (s, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 6.71 (d, 1H, dithiolate aromatic), 4.32 (m, 4H, CH2 of ethyl groups), 2.48 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 2.35 (q, 4H, CH2 of ethyl groups on bodipy), 1.45 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 1.36 (t, 6H, CH3 of ethyl groups), 0.99 (m, 6H, CH3 of ethyl groups). EI-MS(m/z): 954 [M+H]+, 934 [M-F]+. Anal. Calcd for C39H42BF2N4O3PPtS2: C, 49.11; H, 4.44; N, 5.87. Found: C, 49.54; H, 4.54; N, 5.57.

Bodipy-C6H4P(O)(OEt)2, 6.

The compounds 3-ethyl-2,4-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (356 mg, 2.89 mmol) and diethyl (4-formylphenyl)phosphonate (349 mg, 1.44 mmol) were dissolved in dry CH2Cl2 (110 mL). Trifluoroacetic acid (two drops) was added to the solution, which was stirred at room temperature overnight. DDQ (327 mg, 1.44 mmol) was added in a single portion, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 h. N,N-diisopropylethylamine (2.8 mL, 16 mmol) and BF3·Et2O (2.8 mL, 23 mmol) were added, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 h. The reaction mixture was washed with water (3 × 20 mL) and brine (3 × 20 mL). The separated organic fractions were dried with MgSO4 before the solvent was removed. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel, using toluene/CH3CN (4:1) as eluant (297 mg, 40% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 7.97 (m, 2 H, benzene aromatic), 7.44 (m, 2 H, benzene aromatic), 4,20 (m, 4H, CH2 of ethyl groups), 2.53 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 2.32 (q, 4H, CH2 of ethyl groups on bodipy), 1.36 (t, 6H, CH3 of ethyl groups), 1.25 (s, 6H, CH3 on bodipy), 0.99 (t, 6H, CH3 of ethyl groups). EI-MS(m/z): 517 [M+H]+, 497 [M-F]+. Anal. Calcd for C27H36BF2N2O3P: C, 62.80; H, 7.03; N, 5.43. Found: C, 62.68; H, 7.23; N, 5.45.

Attachment of Dyads, Complexes, and Bodipy Dye 6 to TiO2.

A total of 2.5 mL of a stock solution of the photosensitizer in CH3CN (50 μM) [or in CH2Cl2 for 1(bpyC) and 4(bpyC)] was added to a 20-mL vial containing 20 mg of platinized TiO2. The sample vial was sonicated for 20 min in the dark and the platinized TiO2 particles were immediately separated by centrifugation and dried under vacuum. The photosensitizer-attached Pt-TiO2 sample was then transferred to a 40-mL vial to which 5 mL of aqueous ascorbic acid solution (0.5 M, pH 4.0) was added. For samples prepared by this method, hydrogen evolution studies were conducted in aqueous media, rather than 1:1 vol/vol CH3CN/H2O.

Hydrogen Evolution Studies.

The 40-mL sample vials were placed into a temperature-controlled block at 15 °C and each vial was sealed with an air-tight cap fitted with a pressure transducer and a rubber septum. The samples were then purged with a mixture of gas containing N2/CH4 (79:21 mol %). The methane present in the gas mixture serves as an internal reference for GC analysis at the end of the experiment. The samples were irradiated in a locally built 16-well photolysis apparatus with high-power green (530 nm) LUXEON Rebel LEDs, mounted on a 20-mm Star CoolBase-161 lm at 700 mA atop an orbital shaker. The light power of each LED was set to 130 mW and measured with an L30 A Thermal sensor and a Nova II power meter (Ophir- Spiricon). The pressure changes in the vials were recorded using a Labview program from a Freescale semiconductor sensor (MPX4259A series). At the end of the experiment, the headspaces of the vials were characterized by gas chromatography to ensure that the measured pressure change was a consequence of hydrogen generation and to confirm the amount of hydrogen generated. The amounts of hydrogen evolved were determined using a Shimadzu GC-17A gas chromatograph with a 5-Å molecular sieve column (30 m, 0.53 mm) and a thermal conductivity detector and were quantified by a calibration plot to the internal CH4 standard.

SI Appendix contains the following: 1H NMR spectra of the Pt chromophores; cyclic voltammograms of 1(bpyCH2P), 1(phenP), 4(bpyCH2P), 5(phenP); preparation of Pt-TiO2; comparison of the UV-vis spectra of chromophores in CH3CN (or CH2Cl2) before and after sonication; and H2 production using various chromophores. Complete crystallographic information is available in CIF format.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Collaborative Research Grant CHE-1151789. Additionally, D.W.M. was supported as an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow, R.P.S. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, and W.-F.F. was supported by the China Scholarship Council under the State Scholarship Fund during his stay at the University of Rochester.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, United Kingdom (CCDC reference nos. 1401012–1401014).

See Commentary on page 9146.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1509310112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schultz MG, Diehl T, Brasseur GP, Zittel W. Air pollution and climate-forcing impacts of a global hydrogen economy. Science. 2003;302(5645):624–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1089527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blankenship RE. Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis. Blackwell; Oxford: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawlor DW. Photosynthesis. Springer; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregory RPF. Biochemistry of Photosynthesis. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youngblood WJ, et al. Photoassisted overall water splitting in a visible light-absorbing dye-sensitized photoelectrochemical cell. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(3):926–927. doi: 10.1021/ja809108y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alstrum-Acevedo JH, Brennaman MK, Meyer TJ. Chemical approaches to artificial photosynthesis. 2. Inorg Chem. 2005;44(20):6802–6827. doi: 10.1021/ic050904r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer TJ. Chemical approaches to artificial photosynthesis. Acc Chem Res. 1989;22(5):163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graetzel M. Artificial photosynthesis: Water cleavage into hydrogen and oxygen by visible light. Acc Chem Res. 1981;14(12):376–384. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberg R, Nocera DG. Preface: Overview of the forum on solar and renewable energy. Inorg Chem. 2005;44(20):6799–6801. doi: 10.1021/ic058006i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakraborty S, Wadas TJ, Hester H, Schmehl R, Eisenberg R. Platinum chromophore-based systems for photoinduced charge separation: A molecular design approach for artificial photosynthesis. Inorg Chem. 2005;44(20):6865–6878. doi: 10.1021/ic0505605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hara M, et al. Cu2O as a photocatalyst for overall water splitting under visible light irradiation. Chem Commun. 1998;(3):357–358. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khaselev O, Turner JA. A monolithic photovoltaic-photoelectrochemical device for hydrogen production via water splitting. Science. 1998;280(5362):425–427. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuji I, Kato H, Kobayashi H, Kudo A. Photocatalytic H2 evolution reaction from aqueous solutions over band structure-controlled (AgIn)xZn2(1-x)S2 solid solution photocatalysts with visible-light response and their surface nanostructures. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(41):13406–13413. doi: 10.1021/ja048296m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujishima A, Honda K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature. 1972;238(5358):37–38. doi: 10.1038/238037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehn JM, Sauvage JP. Chemical storage of light energy. Catalytic generation of hydrogen by visible light or sunlight. Irradiation of neutral aqueous solutions. Nouv J Chim. 1977;1(6):449–451. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller P, Moradpour A, Amouyal E, Kagan HB. Hydrogen production by visible-light using viologen-dye mediated redox cycles. Nouv J Chim. 1980;4(6):377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirch M, Lehn J-M, Sauvage J-P. Hydrogen generation by visible light irradiation of aqueous solutions of metal complexes. An approach to the photochemical conversion and storage of solar energy. Helv Chim Acta. 1979;62(4):1345–1384. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moradpour A, Amouyal E, Keller P, Kagan H. Hydrogen production by visible light irradiation of aqueous solutions of tris(2,2′-bipyridine)ruthenium(2+) Nouv J Chim. 1978;2(6):547–549. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalyanasundaram K, Kiwi J, Grätzel M. Hydrogen evolution from water by visible light, a homogeneous three component test system for redox catalysis. Helv Chim Acta. 1978;61(7):2720–2730. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furlong DN, Wells D, Sasse WHF. Colloidal semiconductors in systems for the sacrificial photolysis of water: Sensitization of titanium dioxide by adsorption of ruthenium complexes. J Phys Chem. 1986;90(6):1107–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmans R, Frank AJ. A molecular water-reduction catalyst: Surface derivatization of titania colloids and suspensions with a platinum complex. J Phys Chem. 1991;95(23):9438–9443. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borgarello E, Kiwi J, Pelizzetti E, Visca M, Gratzel M. Photochemical cleavage of water by photocatalysis. Nature. 1981;289(5794):158–160. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esswein AJ, Nocera DG. Hydrogen production by molecular photocatalysis. Chem Rev. 2007;107(10):4022–4047. doi: 10.1021/cr050193e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M, Na Y, Gorlov M, Sun L. Light-driven hydrogen production catalysed by transition metal complexes in homogeneous systems. Dalton Trans. 2009;(33):6458–6467. doi: 10.1039/b903809d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han Z, Eisenberg R. Fuel from water: The photochemical generation of hydrogen from water. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47(8):2537–2544. doi: 10.1021/ar5001605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han Z, Qiu F, Eisenberg R, Holland PL, Krauss TD. Robust photogeneration of H2 in water using semiconductor nanocrystals and a nickel catalyst. Science. 2012;338(6112):1321–1324. doi: 10.1126/science.1227775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das A, Han Z, Haghighi MG, Eisenberg R. Photogeneration of hydrogen from water using CdSe nanocrystals demonstrating the importance of surface exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(42):16716–16723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316755110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckenhoff WT, McNamara WR, Du P, Eisenberg R. Cobalt complexes as artificial hydrogenases for the reductive side of water splitting. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2013;1827(8–9):958–973. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckenhoff WT, Eisenberg R. Molecular systems for light driven hydrogen production. Dalton Trans. 2012;41(42):13004–13021. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30823a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, et al. A photoelectrochemical device for visible light driven water splitting by a molecular ruthenium catalyst assembled on dye-sensitized nanostructured TiO2. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46(39):7307–7309. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01828g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brimblecombe R, Koo A, Dismukes GC, Swiegers GF, Spiccia L. Solar driven water oxidation by a bioinspired manganese molecular catalyst. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(9):2892–2894. doi: 10.1021/ja910055a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Juris A, et al. Ru(II) polypyridine complexes: Photophysics, photochemistry, electrochemistry, and chemiluminescence. Coord Chem Rev. 1988;84(0):85–277. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collin JP, et al. Photoinduced processes in dyads and triads containing a ruthenium(II)-bis(terpyridine) photosensitizer covalently linked to electron donor and acceptor groups. Inorg Chem. 1991;30(22):4230–4238. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cline ED, Adamson SE, Bernhard S. Homogeneous catalytic system for photoinduced hydrogen production utilizing iridium and rhodium complexes. Inorg Chem. 2008;47(22):10378–10388. doi: 10.1021/ic800988b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Du P, Knowles K, Eisenberg R. A homogeneous system for the photogeneration of hydrogen from water based on a platinum(II) terpyridyl acetylide chromophore and a molecular cobalt catalyst. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(38):12576–12577. doi: 10.1021/ja804650g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du P, Eisenberg R. Energy upconversion sensitized by a platinum(ii) terpyridyl acetylide complex. Chem Sci. 2010;1(4):502–506. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jarosz P, et al. Platinum(II) terpyridyl acetylide complexes on platinized TiO2: Toward the photogeneration of H2 in aqueous media. Inorg Chem. 2009;48(20):9653–9663. doi: 10.1021/ic9001913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimidzu T, Iyoda T, Koide Y. An advanced visible-light-induced water reduction with dye-sensitized semiconductor powder catalyst. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107(1):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mau AWH, Johansen O, Sasse WHF. Xanthene dyes as sensitizers for the photoreduction of water. Photochem Photobiol. 1985;41(5):503–509. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hashimoto K, Kawai T, Sakata T. The mechanism of photocatalytic hydrogen-production with halogenated fluorescein derivatives. New J Chem. 1984;8(11):693–700. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misawa H, Sakuragi H, Usui Y, Tokumaru K. Photosensitizing action of Eosin-y for visible-light induced hydrogen evolution from water. Chem Lett. 1983;12(7):1021–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuleta JA, Burberry MS, Eisenberg R. Platinum(II) diimine dithiolates. New solution luminescent complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 1990;97(0):47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuleta JA, Bevilacqua JM, Eisenberg R. Solvatochromic and emissive properties of Pt(II) complexes with 1,1- and 1,2-ditholates. Coord Chem Rev. 1991;111(0):237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paw W, et al. Luminescent platinum complexes: Tuning and using the excited state. Coord Chem Rev. 1998;171(0):125–150. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cummings SD, Eisenberg R. Tuning the excited-state properties of platinum(II) diimine dithiolate complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118(8):1949–1960. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Islam A, et al. Dye sensitization of nanocrystalline titanium dioxide with square planar platinum(II) diimine dithiolate complexes. Inorg Chem. 2001;40(21):5371–5380. doi: 10.1021/ic010391y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geary EA, et al. Synthesis, structure, and properties of [Pt(II)(diimine)(dithiolate)] dyes with 3,3′-, 4,4′-, and 5,5′-disubstituted bipyridyl: Applications in dye-sensitized solar cells. Inorg Chem. 2005;44(2):242–250. doi: 10.1021/ic048799t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Connick WB, Gray HB. Photooxidation of platinum(II) diimine dithiolates. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119(48):11620–11627. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, Du P, Schneider J, Jarosz P, Eisenberg R. Photogeneration of hydrogen from water using an integrated system based on TiO2 and platinum(II) diimine dithiolate sensitizers. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(25):7726–7727. doi: 10.1021/ja071789h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galletta M, et al. Absorption spectra, photophysical properties, and redox behavior of ruthenium(II) polypyridine complexes containing accessory dipyrromethene-BF2 chromophores. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110(13):4348–4358. doi: 10.1021/jp057094p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lazarides T, et al. Sensitizing the sensitizer: The synthesis and photophysical study of bodipy-Pt(II)(diimine)(dithiolate) conjugates. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(2):350–364. doi: 10.1021/ja1070366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sabatini RP, et al. Deactivating unproductive pathways in multichromophoric sensitizers. J Phys Chem A. 2014;118(45):10663–10672. doi: 10.1021/jp508283d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shrestha M, et al. Dual functionality of BODIPY chromophore in porphyrin-sensitized nanocrystalline solar cells. J Phys Chem C. 2012;116(19):10451–10460. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galletta M, Campagna S, Quesada M, Ulrich G, Ziessel R. The elusive phosphorescence of pyrromethene-BF2 dyes revealed in new multicomponent species containing Ru(II)-terpyridine subunits. Chem Commun. 2005;(33):4222–4224. doi: 10.1039/b507196h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nepomnyashchii AB, Pistner AJ, Bard AJ, Rosenthal J. Synthesis, photophysics, electrochemistry and electrogenerated chemiluminescence of PEG-modified BODIPY dyes in organic and aqueous solutions. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2013;117(11):5599–5609. doi: 10.1021/jp312166w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosenthal J, Nepomnyashchii AB, Kozhukh J, Bard AJ, Lippard SJ. Synthesis, photophysics, electrochemistry and electrogenerated chemiluminescence of a homologous set of BODIPY-appended bipyridine derivatives. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2011;115(36):17993–18001. doi: 10.1021/jp204487r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qi H, Teesdale JJ, Pupillo RC, Rosenthal J, Bard AJ. Synthesis, electrochemistry, and electrogenerated chemiluminescence of two BODIPY-appended bipyridine homologues. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(36):13558–13566. doi: 10.1021/ja406731f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Connelly NG, Geiger WE. Chemical redox agents for organometallic chemistry. Chem Rev. 1996;96(2):877–910. doi: 10.1021/cr940053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ooyama Y, et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells based on donor-acceptor π-conjugated fluorescent dyes with a pyridine ring as an electron-withdrawing anchoring group. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(32):7429–7433. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brewster TP, et al. Hydroxamate anchors for improved photoconversion in dye-sensitized solar cells. Inorg Chem. 2013;52(11):6752–6764. doi: 10.1021/ic4010856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hirva P, Haukka M. Effect of different anchoring groups on the adsorption of photoactive compounds on the anatase (101) surface. Langmuir. 2010;26(22):17075–17081. doi: 10.1021/la102468s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baik C, et al. Organic dyes with a novel anchoring group for dye-sensitized solar cell applications. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2009;201(2–3):168–174. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mao J, et al. Stable dyes containing double acceptors without COOH as anchors for highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(39):9873–9876. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang L, Cole JM, Dai C. Variation in optoelectronic properties of azo dye-sensitized TiO2 semiconductor interfaces with different adsorption anchors: Carboxylate, sulfonate, hydroxyl and pyridyl groups. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(10):7535–7546. doi: 10.1021/am502186k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sabatini RP, et al. From seconds to femtoseconds: Solar hydrogen production and transient absorption of chalcogenorhodamine dyes. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(21):7740–7750. doi: 10.1021/ja503053s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han Z, Shen L, Brennessel WW, Holland PL, Eisenberg R. Nickel pyridinethiolate complexes as catalysts for the light-driven production of hydrogen from aqueous solutions in noble-metal-free systems. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(39):14659–14669. doi: 10.1021/ja405257s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McNamara WR, et al. Cobalt-dithiolene complexes for the photocatalytic and electrocatalytic reduction of protons in aqueous solutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(39):15594–15599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120757109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bae E, Choi W. Effect of the anchoring group (carboxylate vs phosphonate) in Ru-complex-sensitized TiO2 on hydrogen production under visible light. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110(30):14792–14799. doi: 10.1021/jp062540+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luo G-G, et al. The relationship between the boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) structure and the effectiveness of homogeneous and heterogeneous solar hydrogen-generating systems as well as DSSCs. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17(15):9716–9729. doi: 10.1039/c5cp00732a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sabatini RP, et al. Intersystem crossing in halogenated Bodipy chromophores used for solar hydrogen production. J Phys Chem Lett. 2011;2(3):223–227. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abe R, Hara K, Sayama K, Domen K, Arakawa H. Steady hydrogen evolution from water on Eosin Y-fixed TiO2 photocatalyst using a silane-coupling reagent under visible light irradiation. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2000;137(1):63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Q, et al. Ortho-Dihydroxyl-9,10-anthraquinone dyes as visible-light sensitizers that exhibit a high turnover number for hydrogen evolution. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16(14):6550–6554. doi: 10.1039/c4cp00626g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miyoshi D, Karimata H, Wang Z-M, Koumoto K, Sugimoto N. Artificial G-wire switch with 2,2′-bipyridine units responsive to divalent metal ions. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(18):5919–5925. doi: 10.1021/ja068707u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Norris MR, et al. Synthesis of phosphonic acid derivatized bipyridine ligands and their ruthenium complexes. Inorg Chem. 2013;52(21):12492–12501. doi: 10.1021/ic4014976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mitrofanov A, et al. Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of mono- and diphosphorylated 1,10-phenanthrolines. Synthesis. 2012;44(24):3805–3810. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Price JH, Williamson AN, Schramm RF, Wayland BB. Palladium(II) and platinum(II) alkyl sulfoxide complexes. Examples of sulfur-bonded, mixed sulfur- and oxygen-bonded, and totally oxygen-bonded complexes. Inorg Chem. 1972;11(6):1280–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hissler M, et al. Platinum diimine bis(acetylide) complexes: Synthesis, characterization, and luminescence properties. Inorg Chem. 2000;39(3):447–457. doi: 10.1021/ic991250n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adams CJ, James SL, Liu X, Raithby PR, Yellowlees LJ. Synthesis and characterisation of new platinum-acetylide complexes containing diimine ligands. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 2000;(1):63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Field JS, Haines RJ, Summerton GC. Synthesis and crystal structure determination of the triflate salt of diacetonitrile(2,2′-bipyridine)platinum(II) J Coord Chem. 2003;56(13):1149–1155. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morisue M, Haruta N, Kalita D, Kobuke Y. Efficient charge injection from the S2 photoexcited state of special-pair mimic porphyrin assemblies anchored on a titanium-modified ITO anode. Chemistry. 2006;12(31):8123–8135. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.