Significance

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) is critical to avoid mutations that can lead to genetic disease, cancer, and death. The MMR system is evolutionarily conserved from bacteria to humans and is an example of a remarkable molecular machine. Here we show that this machine operates unidirectionally with respect to the chromosome of Escherichia coli. The most likely explanation for this directionality is that the MMR machinery is associated with the complex responsible for DNA replication. We suggest that this association facilitates the mechanism of strand discrimination in MMR.

Keywords: mismatch repair, recombination, E. coli

Abstract

Defects in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) result in elevated mutagenesis and in cancer predisposition. This disease burden arises because MMR is required to correct errors made in the copying of DNA. MMR is bidirectional at the level of DNA strand polarity as it operates equally well in the 5′ to 3′ and the 3′ to 5′ directions. However, the directionality of MMR with respect to the chromosome, which comprises parental DNA strands of opposite polarity, has been unknown. Here, we show that MMR in Escherichia coli is unidirectional with respect to the chromosome. Our data demonstrate that, following the recognition of a 3-bp insertion-deletion loop mismatch, the MMR machinery searches for the first hemimethylated GATC site located on its origin-distal side, toward the replication fork, and that resection then proceeds back toward the mismatch and away from the replication fork. This study provides support for a tight coupling between MMR and DNA replication.

DNA can be mutated following damage caused by exposure to chemical or physical mutagens or by errors in DNA metabolism, during replication, recombination, or repair (1). Although replicative DNA polymerases have proofreading activities, they cannot avoid a low frequency of incorporation of noncomplementary deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs). It has been estimated that there are 10−5–10−6 misincorporation events per replicated base pair (2). Uncorrected errors of this kind (known as mismatches) will be converted into mutations, which have the potential to perturb biological processes in the next round of DNA replication. The DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is a key DNA guardian that ensures the removal of the misincorporated nucleotides and thereby maintains genomic integrity. The MMR system has a defined substrate range, with different efficiencies of correction of single base mismatches and a 3–4 base size limit for the correction of insertion/deletion loops (IDLs) (3–6). This system is conserved in almost all organisms, with the exception of most Actinobacteria and Mollicutes, and parts of the archaea (7).

When the replication machinery inserts a noncomplementary dNTP in the nascent strand of the E. coli chromosome, the MutS protein binds to the mismatch and recruits the MutL protein (8). These two proteins activate the endonuclease MutH, which nicks the unmethylated strand of a hemimethylated GATC site to initiate removal of the nascent strand containing the mismatch (9, 10). Following the passage of the replisome, GATC motifs remain transiently hemimethylated before methylation of the nascent strand by the Dam methyltransferase enzyme and can therefore be used to distinguish between parental and nascent strands (11, 12). In vitro, MutH can distinguish between these strands by using hemimethylated GATC motifs located within a 2-kb distance of the mismatch, either on the 3′ or the 5′ side (13, 14). UvrD helicase uses the incision made by MutH at the hemimethylated GATC motif as an entry point to unwind the nascent strand. One or more of the four exonucleases (ExoI, ExoVII, RecJ, and ExoX), depending on the required polarity of degradation, resects the unwound nascent strand (15, 16). The single-stranded parental DNA is immediately bound by the single-strand DNA-binding protein (SSB) (17). The DNA polymerase III holoenzyme then correctly resynthesizes the nascent strand and DNA ligase seals the remaining nick (16, 18).

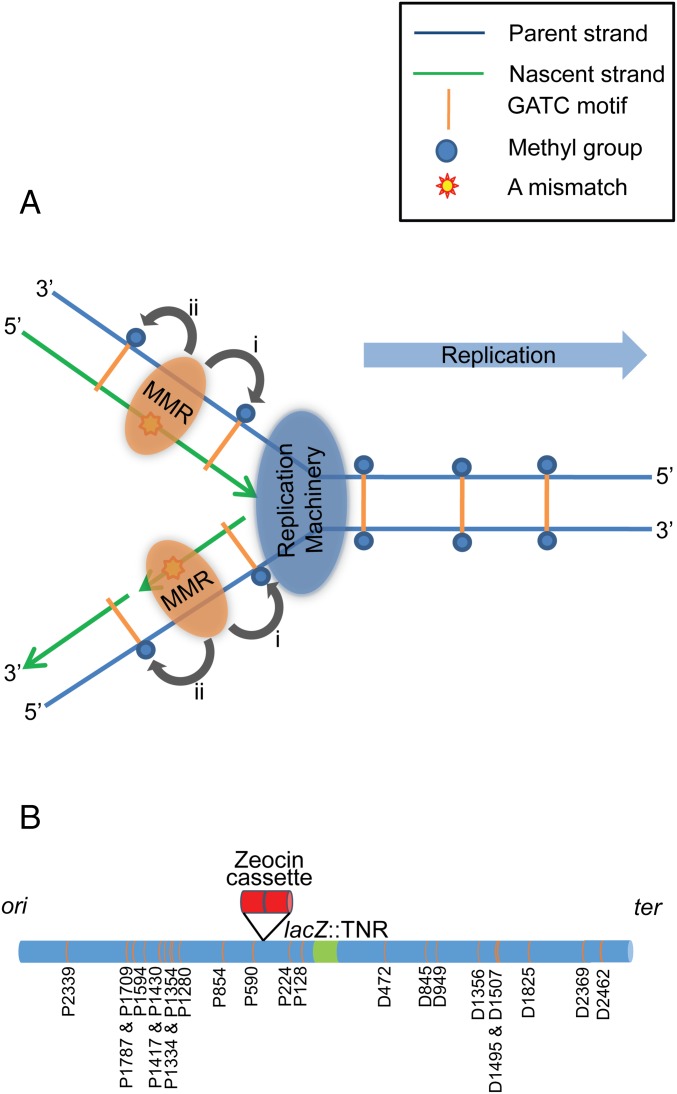

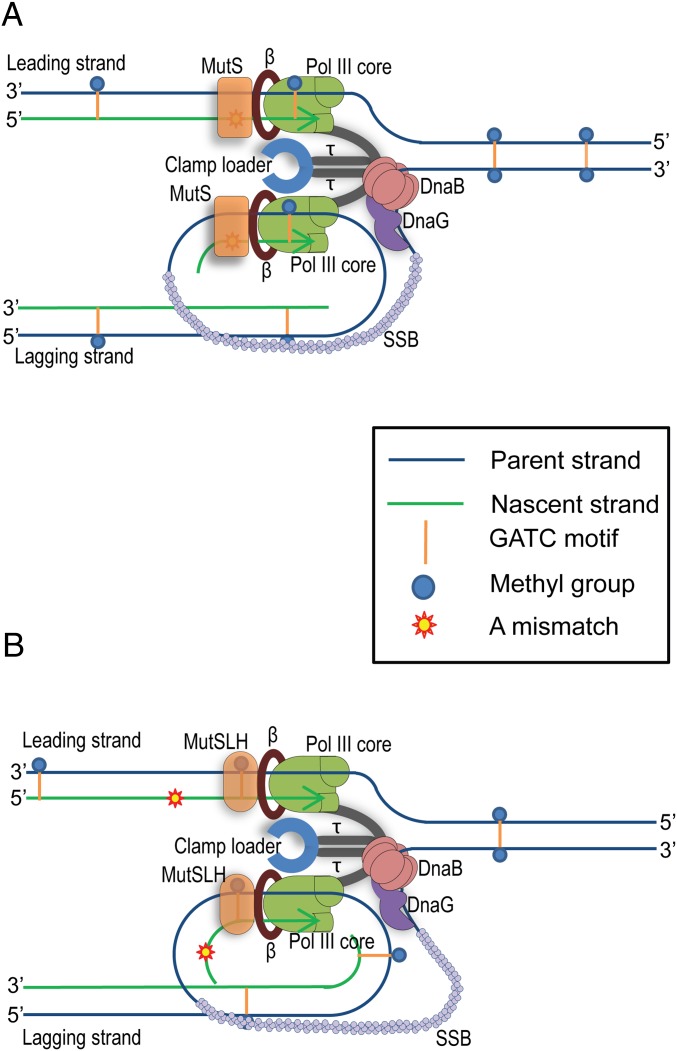

Most of the previous studies of MMR have been based on in vitro experiments using linear or closed-circular heteroduplex DNA substrates in defined systems (19–21). These in vitro studies have shown that an incision of the nascent strand can occur either on the 3′ or the 5′ side of a mismatch, depending on the position of the hemimethylated GATC motif recognized by MutH (22, 23). Using electron microscopy and end labeling, Grilley et al. have shown that the single-stranded DNA region created after an excision reaction lies between the mismatch and the closest GATC motif (15). A hemimethylated GATC motif recognized on the 3′ side of the mismatch requires a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease (e.g., ExoI or ExoX), and ExoVII or RecJ cleaves the single-stranded DNA when a hemimethylated GATC motif is recognized on the 5′ side of the mismatch (5′ to 3′ cleavage).Therefore, in vitro, the cleavage reaction of the MMR system is bidirectional (15, 16). However, in vivo, an MMR system that is bidirectional with respect to DNA polarities could nevertheless be unidirectional with respect to the chromosome. In fact, a unique directionality of MMR with respect to DNA replication would explain the evolution of bidirectionality at the level of strand polarities as mismatches on both the leading and lagging strands need to be repaired. Fig. 1A distinguishes directionality at the level of strand polarity from directionality at the level of the chromosome and illustrates how directionality relative to the replication fork can lead to bidirectionality of resection polarities. Blackwood and collaborators found that MMR at the site of an unstable trinucleotide repeat (TNR) array caused a stimulation of recombination at a nearby 275-bp tandem repeat. This stimulation occurred only when the tandem repeat was placed on the origin-proximal side the TNR that had generated a high frequency substrate for MMR (24). This result suggested that MMR might be directional in a chromosomal context. We have now tested this hypothesis and shown that the MMR system of E. coli has a unique chromosomal directionality.

Fig. 1.

Directionality of MMR. (A) Visualization of MMR in the context of DNA replication. The two possible directionalities of MMR with respect to the chromosome are depicted in the context of the replication fork where mismatches arise. The MMR complex has the potential to scan the chromosome for a hemimethylated GATC site in the direction of movement of the replication fork (i) or in the opposite direction, away from the replication fork (ii). Mismatches are shown on both the leading and lagging strands. However, in reality they are most likely to be present in either one or other of these two locations at a given time. It can be seen that if the scanning for a hemimethylated GATC is unidirectional with respect to the chromosome because of the direction of movement of the replication fork, this can lead to bidirectional resection to repair mismatches on both the leading and the lagging strands. (B) Schematic representation of the locus of interest and the experimental design to investigate the influence of GATC sites on MMR and tandem repeat recombination associated with MMR. The native GATC motifs within the 5-kb region surrounding the CTG⋅CAG TNR array are shown. There are thirteen GATC motifs within the 2.5-kb region on the origin-proximal side of the TNR, of which, two (P128 and P224) are situated between the TNR and the site of insertion of the zeocin cassette. On the origin-distal side of the TNR, there are nine GATC motifs in the first 2.5-kb region. The E. coli chromosome is shown as a horizontal blue cylinder, the TNR is shown as a green band and the zeocin cassette is shown as two tandem red cylinders. GATC motifs are shown by amber bands with their respective names based on their positions. “P” and “D” correspond to the origin-proximal side and the origin-distal side of the TNR, respectively, whereas the number indicates the distance between the GATC motif and the TNR.

Results

MMR Is Unidirectional in the E. Coli Chromosome.

Length instability at the level of a single trinucleotide unit in a CTG⋅CAG repeat array that is inserted in the chromosome of E. coli is elevated in MMR deficient cells (24). This elevation of mutation occurs to an equal extent in mutS, mutL, and mutH mutants indicating that correction of the 3-base IDL, precursor to a single trinucleotide repeat unit change, occurs by a normal MMR reaction involving recognition by MutS and strand cleavage by MutH (24). This is as expected for a 3-base IDL, which has been shown to be corrected with an efficiency close to that of a G·T mismatch (the best recognized single base mismatch) (6) and contrasts with changes of two or more CTG⋅CAG trinucleotide units, which are not elevated in MMR deficient cells (24), as predicted by the inability of the MMR system to recognize an IDL of 5 bases (6). Accordingly, a CTG⋅CAG repeat array can be used as a source of frequent 3-base IDL mismatches at a defined chromosomal locus for the study of MMR in vivo. In this work, we have used a repeated array of 98 copies of CTG⋅CAG (294 bp) where the CTG repeats are located on the leading-strand template in the lacZ gene of the E. coli chromosome (Fig. 1B). The variation of length of the repeat array at the level of a single trinucleotide unit has been defined as “single-unit instability,” which is used as a quantitative phenotype reflecting the efficiency of the MMR system. We have focused on the directionality of MMR as defined by the use of GATC sites on both sides of the TNR. This was carried out by generating site-specific mutations that modified the GATC sites but retained their coding sequences via synonymous substitutions.

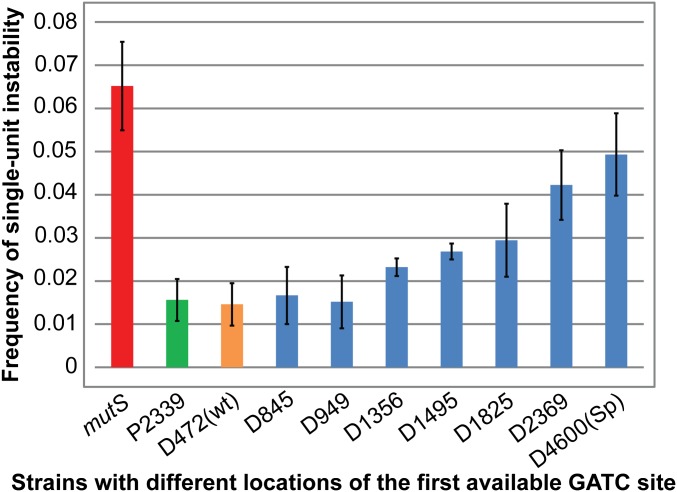

No significant change of single-unit instability was observed following the modification of all of the GATC motifs within a 2.3-kb region on the origin-proximal side of the TNR. In this situation, the next available GATC site was located at a distance of 2,339 bp from the TNR (P2339) and the frequency of single-unit instability remained equivalent to that observed for wild type cells [D472(wt)] (Fig. 2). We conclude that GATC motifs within the first 2.3 kb on the origin-proximal side of the TNR are not required for the excision reaction during DNA mismatch repair while origin-distal GATC motifs are present.

Fig. 2.

MMR as a function of GATC site availability. Frequencies of single-unit instability of the TNR in strains with different distances to the nearest origin-proximal or origin-distal GATC sites. The distance to the first available GATC site from the TNR is indicated on the x axis and the height of the corresponding columns shows the frequency of single-unit instability (y axis). Error bars represent SEs of means. Strains are numbered according to the distance to the first GATC motif present, with “P” and “D” representing the origin-proximal side and the origin-distal side of the TNR respectively. The strain containing the wild-type GATC motif is named D472(wt) and D4600(Sp) represents the strain including a 2.3-kb GATC-free section of S. pombe DNA with a 4.6-kb GATC-free region on the origin-distal side of the TNR. The mutS strain refers to the strain D472 mutS TNR+ in the Table S1, which contains all of the native GATC sites from the chromosome. All of the strains used in this assay contain the TNR.

On the other hand, the frequency of single-unit instability of the TNR started to increase when GATC motifs beyond 1 kb were modified on the origin-distal side of the TNR (D1356 onward in Fig. 2), while keeping the origin-proximal GATC motifs intact. The level of single-unit instability increased 2.9-fold over that observed for [D472(wt)] when all of the available GATC motifs within a 2-kb region on the original-distal side of the TNR were modified (D2369). However, the level of single-unit instability observed for D2369 did not reach the level of that in a mutS background. The difference of instability frequencies between the mutS background and D2369 is statistically significant at a 95% confidence level (p value = 0.0317), indicating that an in vivo separation of 2 kb between the mismatch and the closest remaining GATC site did not totally abolish MMR. This contrasts with the situation observed in vitro where a separation of 2 kb abrogates MMR (15, 25, 26). Nevertheless, our data clearly show that the DNA mismatch repair system has a preference for recognition of GATC sites on the origin-distal side of the TNR.

Our next step was to extend the distance between the nearest available GATC motif and a mismatch further beyond the 2 kb in vitro limit. As there were many closely spaced GATC motifs just beyond the 2-kb boundary on the origin-distal side of the TNR in the E. coli genome, we extended the GATC-free region by inserting a non E. coli DNA sequence in the strain D2369. A 2.3-kb-long GATC motif-free DNA sequence was isolated from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe and inserted at a site 200 bp from the TNR on the origin-distal side. In that strain [D4600(Sp)], the total length of GATC motif-free sequence on the origin-distal side of the TNR reached 4.6 kb. The frequency of single-unit instability in this strain rose close to that observed for a DNA mismatch repair deficient background (mutS; p value = 0.9451 at 95% confidence level), indicating little or no MMR (Fig. 2). This implies that the GATC sites on the origin proximal side of the TNR (which remained present in this situation) were not used to direct repair.

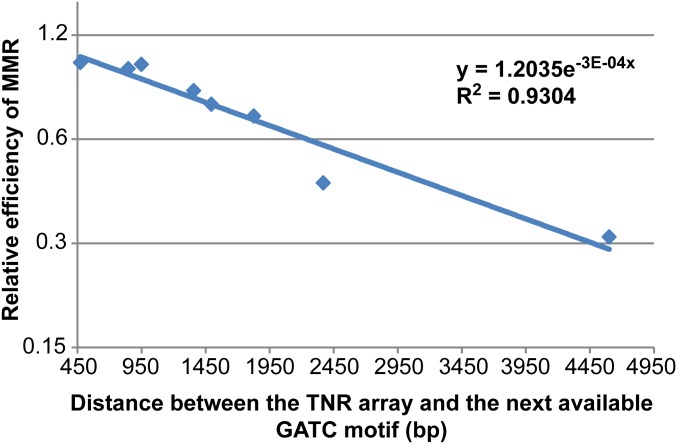

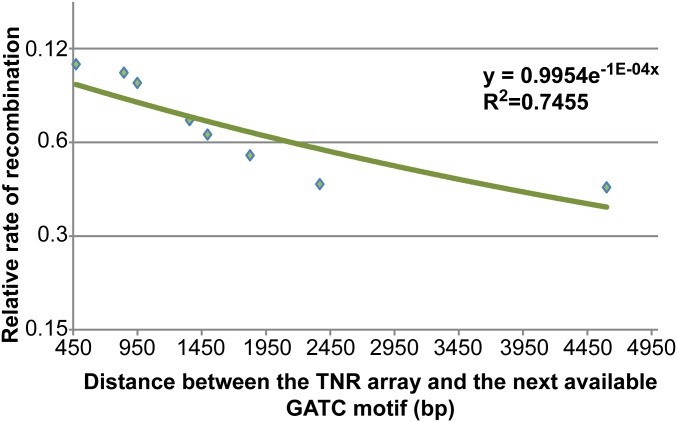

Our data have allowed us to calculate the relative efficiency of MMR as a function of the distance between a mismatch and its nearest GATC motif on the origin-distal side of the TNR (Fig. S1). The efficiency of the MMR system in a wild type cell has been defined as 1 and that in a mutS mutant has been set to 0. Sequential modifications of GATC motifs on the origin-distal side result in the loss of efficiency of MMR as depicted in Fig. S1. Fitting an exponential trend line to the data reveals that the MMR system is 50% less efficient when the distance between the TNR and the next available GATC motif is 2.8 kb.

Fig. S1.

Relative efficiencies of MMR as a function of the distance between the TNR and the next available GATC motif. Distances between the TNR and the next available GATC motif on its origin-distal side are plotted along the x axis and the relative efficiencies of MMR are plotted (on a logarithmic scale) along the y axis. The exponential trend line has been drawn using the built in module of Microsoft Excel and the R2 value is indicated in the graph.

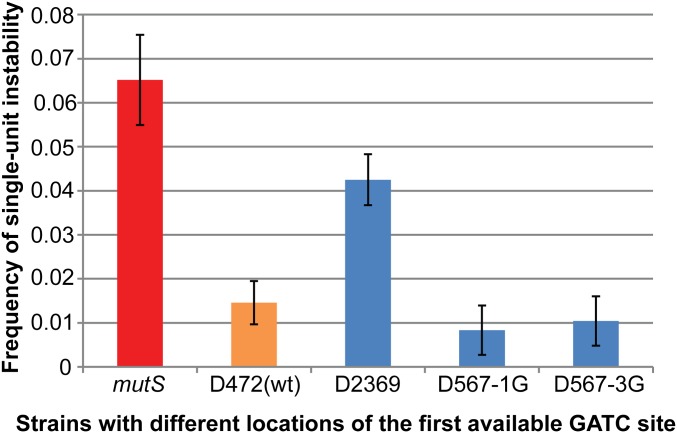

To determine whether a single origin-distal GATC site located close to the TNR was able to restore MMR, we inserted an ectopic GATC site (via synonymous substitution) at 567 bp on the origin-distal side of the TNR in the strain D2369 (D567-1G; Fig. S2). In this strain, the frequency of single-unit instability of the TNR returned to a similar level to that observed in wild type cells [D472(wt)]. This experiment suggested that a single origin-distal GATC site at 567 bp from the TNR was efficiently recognized. To confirm that this site was indeed recognized at close to 100% efficiency, we modified the same region (567 bp origin distal to the TNR) to include three tandemly repeated GATC sites (D567-3G). Because that did not further increase the efficiency of MMR we concluded that a single origin-distal GATC site at this distance from the TNR was already recognized with maximal efficiency.

Fig. S2.

The MMR system efficiently recognizes a single close origin-distal GATC site. The distance to the first available GATC site is indicated on the x axis and the height of the corresponding columns shows the frequency of single-unit instability (y axis). Error bars represent SEs of means. Strains are numbered according to the distance to the first GATC motif present, with “D” representing the origin-distal side of the TNR. The D472(wt) and the mutS strains contain all of the native GATC sites from the chromosome. The strains D567-1G and D567-3G are derivatives of the strain D2369 that respectively contain one GATC site and three tandem GATC sites at 567 bp on the origin-distal side of the TNR.

The Efficiency of MMR Depends on the Length of the Excision Tract.

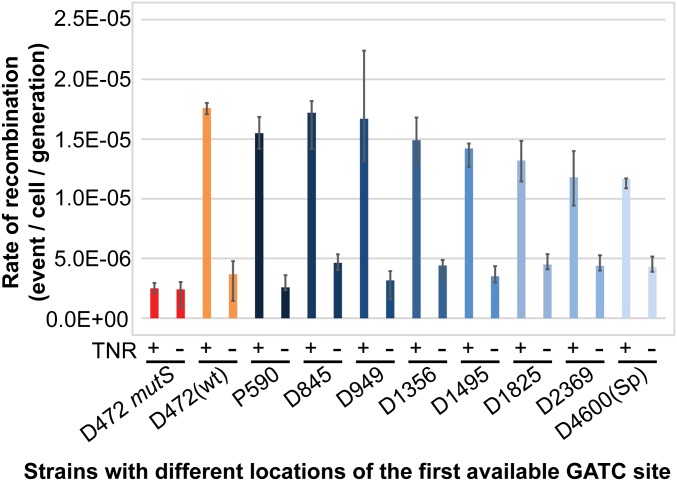

To investigate whether the observed decrease in efficiency of MMR with respect to the separation between the mismatch and the closest origin-distal GATC site was determined by recognition of the GATC site implicated in the reaction or the length of the excision tract, we investigated a second reaction implicating MMR. It has previously been shown that recombination at a split zeocin resistance recombination reporter cassette (zeocin cassette) on the origin-proximal side of a TNR (Fig. S3) is stimulated by MMR (24). The rate of recombination was found to be a function of the distance between the TNR and the zeocin cassette and could be detected as far as 6.3 kb away on the origin-proximal side of the TNR. Here, we have studied the recombination level at the zeocin cassette as a function of the location of the first available GATC site to initiate the MMR reaction. In this experiment, we placed the zeocin cassette at 500 bp on the origin-proximal side of the TNR, as indicated in Fig. 1B. In the absence of the TNR, there was a basal rate of recombination [D472(wt) TNR–; Fig. 3]. This level increased sevenfold in the presence of the TNR [D472(wt) TNR+]. This increase was dependent on MMR as only the basal level of recombination was detected in a mutS mutant containing the TNR (D472 mutS TNR+). This reaction has previously been shown to be dependent on MutS, MutL, and MutH, with the argument that (like MMR) it is dependent on an excision tract initiated by cleavage of a GATC site by MutH endonuclease (24). In MMR proficient cells, mutation of both GATC motifs, P128 and P224, located between the TNR and the zeocin cassette did not affect the level of recombination (P590 TNR+). Therefore, this MMR excision reaction is not influenced by the presence of the GATC motifs between the TNR and the zeocin cassette on the origin-proximal side of the mismatch. A gradual decrease in the rate of recombination at the zeocin cassette was observed when sequential modifications of GATC motifs extended beyond a 1-kb distance on the origin-distal side of the TNR (D1356 TNR+ and beyond). A 15% and a 19% decrease of the rate of recombination were observed, compared with the strain with intact GATC motifs [D472(wt) TNR+], in the strains with the first available GATC motif at 1,356 bp (D1356 TNR+) and 1,825 bp (D1825 TNR+) away on the origin-distal side of the TNR. However, the rate of recombination did not decrease to the level observed in cells devoid of the TNR (TNR–) or mutated in the MMR system (D472 mutS TNR+), even after modification of all GATC motifs within 2 kb (D2369 TNR+) or 4.6 kb [D4600(Sp) TNR+] on the origin-distal side of the TNR (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, these experiments revealed that, as for MMR, the rate of recombination was sensitive to the separation of the TNR and the zeocin cassette from the first available origin-distal GATC site.

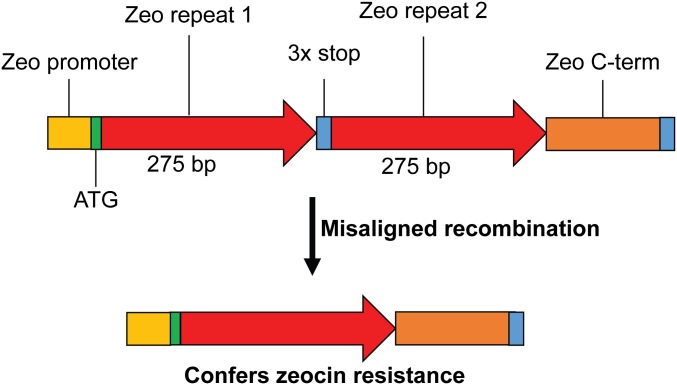

Fig. S3.

Split zeocin resistance recombination cassette. A duplication of two parts of the zeocin resistance gene creates a duplication of 275 bp that can lead to the formation of an intact zeocin resistance gene by misaligned recombination or strand slippage. The N-terminal 275 bp of the gene is followed by 3 stop codons followed by an entire copy of the gene (369 bp) lacking the ATG start site.

Fig. 3.

Tandem repeat recombination as a function of GATC site availability. Rates of recombination at a zeocin cassette in strains with different distances to the nearest origin-proximal or origin-distal GATC sites. The rates of recombination at the zeocin cassette are shown along the y axis for strains with different distances to the first available GATC site from the TNR (indicated along the x axis by the number following “P” for origin-proximal side and “D” for origin-distal side of the TNR). Error bars represent upper and lower limits of 95% confidence intervals.

We have quantified the effect of the distance between the mismatch and the first available GATC site on the origin-distal side of the TNR by plotting the relative recombination efficiency as a function of this distance (see Supporting Information for the calculation of relative recombination efficiencies). Here, we have defined the strain with wild type GATC sites [D472(wt) TNR+] to have a relative recombination efficiency of 1 and the mutS mutant (D472 mutS TNR+) to have a relative recombination efficiency of 0. As can be seen in Fig. S4, the recombination efficiencies decreased as the distance between the first available GATC site and the TNR (or the zeocin cassette) increased. However, the slope of the exponential fitted curve is approximately half that for MMR (compare Figs. S4 and S1). The data predict that a 50% recombination efficiency will be reached when 6 kb separates the first available GATC site and the TNR.

Fig. S4.

Relative efficiencies of recombination as a function of the distance between the TNR and the next available GATC motif. Distances between the TNR and the next available GATC motif on its origin-distal side are plotted along the x axis and the relative efficiencies of recombination are plotted (on a logarithmic scale) along the y axis. The exponential trend line has been drawn using the built in module of Microsoft Excel and the R2 value is shown in the graph.

The observations that the efficiencies of MMR and of zeocin cassette recombination are affected by the separation between the TNR and first available origin-distal GATC site argue that origin-distal GATC sites are implicated in both reactions. However, the difference in the efficiencies of the two reactions was surprising given that both excision to mediate MMR and excision to stimulate zeocin cassette recombination were expected to pass through the TNR and to enable repair. We considered that sensitivity to the separation between the TNR (or zeocin cassette) and the first available origin-distal GATC site might either reflect a diminished probability of recognizing a GATC site with distance from the mismatch or a diminished probability of an excision tract covering the distance between the GATC site recognized and the TNR (or zeocin cassette). Given that there is no reason to expect two different modes of recognition of the same origin-distal GATC site, we argue that two lengths of excision tracts must exist. We propose that MMR is primarily mediated via shorter tracts that do not need to extend far beyond the mismatch, whereas longer tracts are responsible for zeocin cassette recombination at a greater distance beyond the initiating mismatch. Because both reactions are expected to involve excision tracts that remove the mismatch in the TNR, the shorter tracts must be more frequent than the longer tracts to explain the observation of two different efficiencies as a function of separation of the mismatch and the first available origin-distal GATC site. The fact that two reactions, which are initiated at the same GATC sites, are differentially sensitive to the distance of the first origin-distal GATC site from the TNR provides strong evidence that the lengths of the two different classes of excision tracts are the primary in vivo determinants of the ability of a distant GATC to stimulate MMR or recombination.

RecQ Helicase Is Not Implicated in the Longer Excision Tracts.

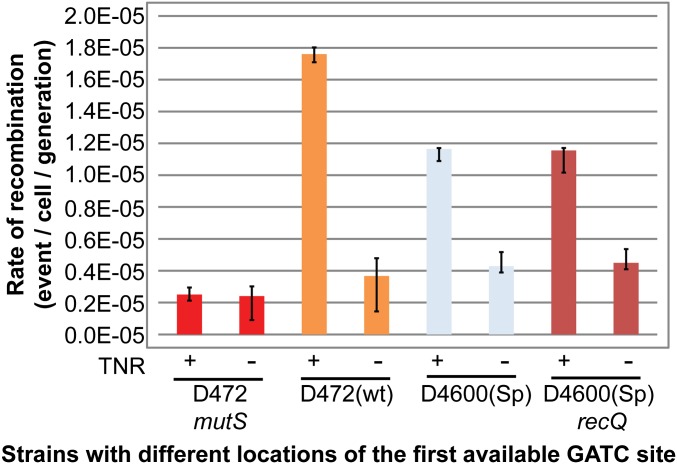

We have tested whether the RecQ helicase might be implicated in the longer excision tracts, by extending excision tracts initiated by UvrD. This was an attractive hypothesis as RecQ is a non-MMR helicase with a 3′ to 5′ directionality that can bind ssDNA—dsDNA junctions and stimulate recombination. However, the rates of recombination at the zeocin cassette were similar independently of the presence of RecQ in strains where 4.6 kb of DNA separated the TNR and the first origin-distal GATC site [D4600(Sp) TNR+] (Fig. S5).

Fig. S5.

RecQ helicase is not responsible for the long ssDNA tract generated during the excision reaction of MMR. This bar plot indicates the rates of recombination at the zeocin cassette (y axis) in different mutated strains (x axis). The error bars represent the upper and lower limits of 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

MMR Is Unidirectional with Respect to the E. coli Chromosome.

We have shown that to correct IDL mismatches the MMR system of E. coli uses the GATC sequences present on the origin-distal side of a TNR located in the chromosomal lacZ gene. Given that IDLs are created during DNA replication and that hemimethylated GATC sites, which direct the strand specificity of MMR, are transiently generated during DNA replication, we propose that it is the first GATC site between the mismatch and the replication fork that is normally recognized during MMR. Unidirectionality of the MMR system with respect to chromosomal DNA replication explains bidirectionality at the level of the strand excision, as MMR is required to occur on both the leading and lagging strand of the replication fork (15).

Our assay relies on the observation that the frequency of single-unit TNR changes (+1 and −1 TNR) in a CTG⋅CAG repeat array is dependent on MMR catalyzed by MutS, MutL, and MutH (24). This is consistent with a conventional MMR reaction to correct a 3-nucleotide IDL, generated in the TNR during DNA replication and known to be a good substrate for MMR (6). For this reason, we have made the simplifying assumption that the TNR is providing an elevated frequency of 3-nucleotide IDLs for conventional MMR detected in our single-unit instability assay. However, we cannot formally exclude the possibility that some other features of the repeat array are contributing to the frequency of single-unit changes. It is well known that trinucleotide repeats can form pseudohairpins in vitro (27–32) that have been implicated in large-scale TNR changes in many experimental systems including the E. coli chromosome (33, 34). We suspect that these large pseudohairpin structures are not implicated in our single-unit TNR changes, but if they are, the repair reaction must involve the three components of conventional MMR (MutS, MutL, and MutH) and must demonstrate the chromosomal directionality that we have detected.

Further experiments are required to determine the molecular basis of this directionality. However, codirectionality of hemimethylated GATC recognition and DNA replication provides a mechanism for origin-distal GATC motif scanning via a known interaction between the MutS protein and the β-clamp (35, 36). Following recognition of the mismatch by an ADP-bound form of MutS, this protein is converted into an ATP-bound sliding clamp (2). The interaction between MutS-ATP and the β-clamp of the replisome would provide the possibility of a rapid and directed scanning for a hemimethylated GATC site on the origin-distal side of the mismatch, as shown in Fig. 4. Upon identification of a hemimethylated GATC site, the incision of the nascent strand would be carried out by MutH in conjunction with the matchmaker protein MutL.

Fig. 4.

Model for the chromosomal directionality of MMR. (A) Recognition of a mismatch by MutS. MutS is closely associated to the replisome through its interaction with the β-clamp. Upon recognition of a mismatch the MutS dimer adopts its ATP-bound form and becomes a sliding clamp. (B) Recognition of an origin-distal hemimethylated GATC site by the MutSLH complex. Through continued association with the β-clamp, MutS slides with the replisome and becomes associated with MutL and MutH. This triple complex recognizes the first hemimethylated GATC site encountered in the direction of replisome movement. In these figures, mismatches are shown on both the leading and lagging strands. However, in reality replisome complexes are likely to encounter a mismatch on either the leading or the lagging strand at a particular time.

The Maximal Distance, Measured Between a GATC Site and a Mismatch, for Productive MMR Is Longer in vivo than in vitro.

Our data suggest that the efficiency of MMR is reduced to 50% in the presence of 2.8 kb of DNA between the mismatch and the GATC site used to initiate resection. This distance is greater than the limit of 2 kb observed in vitro (15, 25, 26). This difference could be explained if scanning for a hemimethylated GATC site is unidirectional in vivo because of the interaction between MutS and the β-clamp (as described in Fig. 4). If so, scanning for a hemimethylated GATC site might in fact not be the factor determining the maximal in vivo distance separating a mismatch and a GATC site for productive MMR, while it might be critical in vitro. We have determined that only seven regions of the E. coli chromosome have GATC motifs separated by distances greater than 2.8 kb. These regions are either derived from prophages or present in rhs loci, which have an unusual base composition and are subject to complex inheritance patterns (37–40).

Different Lengths of MMR Excision Tracts Are Formed.

MMR mediates the repair of mismatches and stimulates recombination at a zeocin cassette located up to 6.3 kb away from a TNR (24). Both reactions involve the recognition of a GATC site on the origin-distal side of the TNR. However, the zeocin cassette recombination reaction implies the existence of longer resection tracts extending beyond that observed in vitro (15). Here, we show that MMR and zeocin cassette recombination are differentially affected by the distance between the first origin-distal GATC site and the TNR. This differential effect argues that two different lengths of excision tracts are generated during MMR. The shorter tracts must be more frequent as they are primarily responsible for MMR and only need to reach the mismatch for repair to occur. We have no evidence for where they terminate. However, they may indeed terminate within 100 nucleotides beyond the mismatch, as demonstrated in vitro (15). The longer excision tracts that lead to zeocin cassette recombination must be less frequent as they do not determine the efficiency of MMR but extend significantly beyond the mismatch. They are less sensitive to the distance between the mismatch and the first GATC site, suggesting that they are intrinsically longer (more processive resection). We have eliminated the possibility that the longer excision tracts are caused by the action of the RecQ helicase. Further work is required to determine the molecular basis of the differences between these lengths of excision tracts. For example, it is known that several alternative nucleases can substitute for each other in excision tract processing (16, 41) and this nuclease choice might determine excision tract length.

The Success of MMR as a Function of the Distance between the Mismatch and the First Origin-Distal GATC Site Is Determined by the Length of the Excision Tract.

We have considered two possibilities to explain the effect of the separation of the mismatch from the first origin-distal GATC site on the efficiency of MMR and of zeocin cassette recombination. First, the recognition of a hemimethylated GATC site is sensitive to the distance from the mismatch. Second, the processivity of resection determines the length of the excision tract. Given that there is no reason to propose two different modes of GATC recognition for excision tracts of different lengths, the fact that these events are differentially affected by the distance between the first origin-distal GATC and the TNR argues that it is the length of the excision tract that determines the success of MMR. This fits with the model presented in Fig. 4, where MutS is carried forward with the replisome facilitating the unidirectional scanning of DNA for a hemimethylated GATC site. We can estimate the length of the excision tracts that mediate MMR assuming that GATC sites are recognized equally well, are recognized independently of their distance from the TNR in the range of distances that we have investigated and that resection from the first origin-distal site (at 472 bp from the TNR) always reaches the mismatch. Given these assumptions, the observation that the efficiency of MMR is reduced to 50% with a separation of 2.8 kb between the mismatch and the first available GATC site argues that 50% of these excision tracts measure this distance. By a similar argument, our data argue that 50% of the excision tracts that mediate zeocin cassette recombination measure 6 kb plus the distance required to uncover at least one copy of the repeated section of the zeocin cassette. Because the zeocin cassette is located 500 bp on the origin-proximal side of the TNR, the zeocin cassette includes a repeated sequence of 275 bp and the TNR measures 294 bp a successful excision tract must reach ∼1.1 kb farther than the distance between the recognized GATC site and the TNR. The 50% length of these longer excision tracts is therefore estimated to be ∼7 kb.

Implications for Eukaryotic MMR Systems.

In eukaryotic cells, MMR is primarily initiated by the MutSα (MSH2/MSH6) or MutSβ (MSH2/MSH3) complex, which is then followed by the MutLα (MLH1/PMS) protein. There is no separate MutH endonuclease homolog. However, MutLα has been shown to have endonuclease activity (42). Strand discrimination is carried out via the recognition of nicks in the nascent strand and it has recently been shown that these nicks can be generated via the removal of ribonucleotides from this DNA strand (43, 44). The roles of helicases and exonucleases in eukaryotic MMR are only partially understood. No helicase has been shown to be required for the resection reaction but this does not exclude the possible involvement of helicases (45). The exonuclease activity of Exo1 can provide 5′ to 3′ resection in the absence of a helicase (46). Furthermore the endonuclease activity of MutLα can nick a strand 5′ of a mismatch that was originally nicked on the 3′ side, allowing access to a 5′ to 3′ nuclease such as Exo1 (42, 47). However, the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activities of polymerases δ and ε have also been implicated in MMR (48). As in E. coli, the eukaryotic MutS complexes interact with the sliding clamp (49, 50). Therefore, whatever the transduction pathway to resection and the final polarity of that resection, we expect that MMR in eukaryotic cells will also show chromosomal directionality.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains.

The construction and genotypes of the strains used are provided in the Supporting Information.

MMR Analysis.

Fragment length analysis of the TNR is described in the Supporting Information.

Recombination Analysis.

Fluctuation analysis of recombination frequencies at the zeocin cassette is described in the Supporting Information.

SI Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains.

Derivatives of E. coli strains harboring CAG⋅CTG repeat arrays in the lacZ gene [lacZ::(CTG)98] were used in this study (33). lacZ::(CTG)98 implies that an array of 98 CTG repeats is located on the leading-strand template and a complementary sequence of 98 repeats of CAG is located on the lagging-strand template. All mutant strains used in this study were constructed using plasmid-mediated gene replacement as described previously (51). A list of the strains used is given in Table S1. The table makes reference to the figures in the text where the strains have been used.

Table S1.

Bacterial strains

| Name used in the text | DL strain number | Genotype* | Source | Corresponding figure(s) |

| D472(wt) TNR+ | DL4150 | lacZ::zeo† lacZ::(CTG)98 | Ewa Okely | Figs. 2, 3, S2, and S5 |

| D472(wt) TNR– | DL4151 | lacZ::zeo | Ewa Okely | Figs. 3 and S5 |

| D472 mutS TNR+ | DL4195 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 mutS | Ewa Okely | Figs. 2, 3, S2, and S5 |

| D472 mutS TNR– | DL4194 | lacZ::zeo mutS | Ewa Okely | Figs. 3 and S5 |

| P590 TNR+ | DL5723 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98P(T130C)‡ P(T226C) | This work | Fig. 3 |

| P590 TNR– | DL5729 | lacZ::zeo P(T130C) P(T226C) | This work | Fig. 3 |

| P2339 | DL5727 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98P(T130C) P(T226C) P(T592C) P(T856C) P(T1282C) P(T1336C) P(C1354T) P(C1417T) P(T1430C) P(C1594T) P(T1709C) P(T1787C) P(T2339C) | This work | Fig. 2 |

| D845 TNR+ | DL4954 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 D(A473G)‡ | This work | Figs. 2 and 3 |

| D845 TNR– | DL4955 | lacZ::zeo D(A473G) | This work | Fig. 3 |

| D949 TNR+ | DL4987 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 D(A473G) D(G845A) | This work | Figs. 2 and 3 |

| D949 TNR– | DL4988 | lacZ::zeo D(A473G) D(G845A) | This work | Fig. 3 |

| D1356 TNR+ | DL5022 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) | This work | Figs. 2 and 3 |

| D1356 TNR– | DL5023 | lacZ::zeo D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) | This work | Fig. 3 |

| D1495 TNR+ | DL5089 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G)D(G1356A) | This work | Figs. 2 and 3 |

| D1495 TNR– | DL5090 | lacZ::zeo D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G)D(G1356A) | This work | Fig. 3 |

| D1825 TNR+ | DL5161 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) | This work | Figs. 2 and 3 |

| D1825 TNR– | DL5162 | lacZ::zeo D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) | This work | Fig. 3 |

| D2369 TNR+ | DL5262 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) D(T1827C) | This work | Figs. 2, 3, and S2 |

| D2369 TNR– | DL5159 | lacZ::zeo D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) D(T1827C) | This work | Fig. 3 |

| D4600(Sp) TNR+ | DL5716 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 lacI::Sp§ D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) D(T1827C) | This work | Figs. 2, 3, and S5 |

| D4600(Sp) TNR– | DL5728 | lacZ::zeo lacI::Sp D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) D(T1827C) | This work | Figs. 3 and S5 |

| D4600(Sp) recQ TNR+ | DL5717 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 lacI::SprecQ + D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) D(T1827C) | This work | Fig. S5 |

| D4600(Sp) recQ TNR– | DL5726 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 lacI::Sp recQ D(A473G) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) D(T1827C) | This work | Fig. S5 |

| D567-1G TNR+ | DL5874 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 D(A473G) D(T568A) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) D(T1827C) | This work | Fig. S2 |

| D567-3G TNR+ | DL 5950 | lacZ::zeo lacZ::(CTG)98 D(A473G) D(T568A) D(T574G) D(581GATC582) D(G845A) D(A950G) D(G1356A) D(C1498T) D(T1509C) D(T1827C) | This work | Fig. S2 |

All strains are originally derived from E. coli K-12 MG1655.

“zeo” refers to the Zeocin cassette.

P(T130C) refers to the synonymous mutation T130C on the origin-proximal (P) side of the TNR, while such a mutation preceded by “D” refers to that on the origin-distal side of the TNR.

“Sp” refers to the 2.3 GATC motif free amplified DNA sequence from S. pombe.

MMR Analysis.

Fragment analysis was used to measure the length of the TNR and from this to estimate the frequency of single-unit instability characteristic of a defect in MMR. Sixty parental colonies were selected and grown overnight in separate LB cultures at 37 °C under agitation. On the next day each culture was diluted, plated on LB agar and grown overnight at 37 °C to produce single colonies. Eight random sibling colonies from each plate were analyzed for repeat array instability by colony PCR. Amplification of TNR tracts was accomplished using primers 6-FAM-5′-TTATGCTTCCGGCTCGTATG-3′ and 5′-GGCGATTAAGTTGGGTAACG-3′ to generate fluorescein labeled DNA fragments. PCR products were separated by capillary electrophoresis through a polyacrylamide medium in an ABI 3730 genetic analyzer. The sizes of the PCR products were compared with GeneScan 1200 LIZ dye size standards. Results were analyzed using GeneMapper software (Life Technologies). The significance of the difference of instabilities among different bacterial populations was calculated using Kruskal–Wallis analysis. The relative efficiency of MMR was calculated as described below.

Recombination Analysis.

The rate of recombination at the zeocin cassette (described in Fig. S3) was estimated by fluctuation analysis of recombination frequencies in parallel cultures. Forty-eight overnight cultures were grown from isolated colonies at 37 °C in low-salt LB broth (0.5 gL−1 NaCl). Recombinant colonies were selected on low-salt LB agar plates containing 35 mg mL−1 of zeocin. Fluctuation test tables were used (52) to calculate the rate of recombination (event/cell/generation) and 95% confidence intervals. The relative efficiency of recombination was calculated as described below.

Calculation of Relative Efficiencies of MMR and of Recombination.

Relative efficiency of MMR.

The relative efficiency of the DNA mismatch repair system has been calculated in the following way.

The relative efficiency of the MMR system in the absence of specific GATC site(s)

where the frequency of corrected mismatches in the presence of all GATC sites is

where F(+) represents the frequency of mutations in the presence of MMR and F(-) is the frequency of mutations in the absence of MMR, and where the frequency of corrected mismatches in the absence of specific GATC sites is

where F(ΔGATC) represents the frequency of mutations in the absence specific GATC sites.

The relative efficiency of MMR in a wild type situation [E(+)] was set to 1

Relative efficiency of recombination.

The relative rate of recombination of the zeocin cassette has been calculated in a similar way.

The relative efficiency of recombination of the zeocin cassette in the absence of specific GATC site(s)

where the rate of recombination in wild type that accompanies mismatch repair events is

where Q(+) represents the rate of recombination in the wild type background in the presence of the TNR array and MMR and Q(-) is the rate of recombination in the presence of the TNR array, but in the absence of MMR, and where the rate of recombination (that accompanies mismatch repair events) in the absence of specific GATC sites (in the presence of the TNR array) is

where Q(ΔGATC) represents the rate of recombination in the absence specific GATC sites (in the presence of the TNR array).

The relative efficiency of recombination in a wild type situation [Z(wt)] was set to 1

Acknowledgments

We thank Elise Darmon and Benura Azeroglu for critical reading of the manuscript and Ewa Okely for bacterial strains. A.M.M.H. was funded by a studentship from the Darwin Trust of Edinburgh. D.R.F.L. was funded by the Medical Research Council (UK).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. P.H. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1505370112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Li G-M. Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 2008;18(1):85–98. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiricny J. Postreplicative mismatch repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(4):a012633. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gradia S, Acharya S, Fishel R. The role of mismatched nucleotides in activating the hMSH2-hMSH6 molecular switch. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(6):3922–3930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schofield MJ, et al. The Phe-X-Glu DNA binding motif of MutS. The role of hydrogen bonding in mismatch recognition. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(49):45505–45508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiricny J, Su SS, Wood SG, Modrich P. Mismatch-containing oligonucleotide duplexes bound by the E. coli mutS-encoded protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(16):7843–7853. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.16.7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker BO, Marinus MG. Repair of DNA heteroduplexes containing small heterologous sequences in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(5):1730–1734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachadyn P. Conservation and diversity of MutS proteins. Mutat Res. 2010;694(1-2):20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su SS, Modrich P. Escherichia coli mutS-encoded protein binds to mismatched DNA base pairs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(14):5057–5061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Hays JB. Mismatch repair in human nuclear extracts: Effects of internal DNA-hairpin structures between mismatches and excision-initiation nicks on mismatch correction and mismatch-provoked excision. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(31):28686–28693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Hays JB. Signaling from DNA mispairs to mismatch-repair excision sites despite intervening blockades. EMBO J. 2004;23(10):2126–2133. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urig S, et al. The Escherichia coli dam DNA methyltransferase modifies DNA in a highly processive reaction. J Mol Biol. 2002;319(5):1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barras F, Marinus MG. The great GATC: DNA methylation in E. coli. Trends Genet. 1989;5(5):139–143. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(89)90054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lahue RS, Su SS, Modrich P. Requirement for d(GATC) sequences in Escherichia coli mutHLS mismatch correction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(6):1482–1486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.6.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruni R, Martin D, Jiricny J. d(GATC) sequences influence Escherichia coli mismatch repair in a distance-dependent manner from positions both upstream and downstream of the mismatch. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(11):4875–4890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.11.4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grilley M, Griffith J, Modrich P. Bidirectional excision in methyl-directed mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(16):11830–11837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burdett V, Baitinger C, Viswanathan M, Lovett ST, Modrich P. In vivo requirement for RecJ, ExoVII, ExoI, and ExoX in methyl-directed mismatch repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(12):6765–6770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121183298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramilo C, et al. Partial reconstitution of human DNA mismatch repair in vitro: Characterization of the role of human replication protein A. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(7):2037–2046. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2037-2046.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahue RS, Au KG, Modrich P. DNA mismatch correction in a defined system. Science. 1989;245(4914):160–164. doi: 10.1126/science.2665076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas DC, Roberts JD, Kunkel TA. Heteroduplex repair in extracts of human HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(6):3744–3751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blackwell L J, Bjornson KP, Modrich P. DNA-dependent activation of the hMutSalpha ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(48):32049–32054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dzantiev L, et al. A defined human system that supports bidirectional mismatch-provoked excision. Mol Cell. 2004;15(1):31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modrich P. Methyl-directed DNA mismatch correction. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(12):6597–6600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Au KG, Welsh K, Modrich P. Initiation of methyl-directed mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(17):12142–12148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackwood JK, Okely EA, Zahra R, Eykelenboom JK, Leach DRF. DNA tandem repeat instability in the Escherichia coli chromosome is stimulated by mismatch repair at an adjacent CAG·CTG trinucleotide repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(52):22582–22586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012906108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pukkila PJ, Peterson J, Herman G, Modrich P, Meselson M. Effects of high levels of DNA adenine methylation on methyl-directed mismatch repair in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1983;104(4):571–582. doi: 10.1093/genetics/104.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Modrich P. Mechanisms and biological effects of mismatch repair. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:229–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gacy AM, Goellner G, Juranić N, Macura S, McMurray CT. Trinucleotide repeats that expand in human disease form hairpin structures in vitro. Cell. 1995;81(4):533–540. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitas M, Yu A, Dill J, Haworth IS. The trinucleotide repeat sequence d(CGG)15 forms a heat-stable hairpin containing Gsyn. Ganti base pairs. Biochemistry. 1995;34(39):12803–12811. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith GK, Jie J, Fox GE, Gao X. DNA CTG triplet repeats involved in dynamic mutations of neurologically related gene sequences form stable duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(21):4303–4311. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu A, Dill J, Mitas M. The purine-rich trinucleotide repeat sequences d(CAG)15 and d(GAC)15 form hairpins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(20):4055–4057. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.20.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu A, et al. The trinucleotide repeat sequence d(GTC)15 adopts a hairpin conformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(14):2706–2714. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petruska J, Hartenstine MJ, Goodman MF. Analysis of strand slippage in DNA polymerase expansions of CAG/CTG triplet repeats associated with neurodegenerative disease. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(9):5204–5210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zahra R, Blackwood JK, Sales J, Leach DRF. Proofreading and secondary structure processing determine the orientation dependence of CAG x CTG trinucleotide repeat instability in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2007;176(1):27–41. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.069724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andreoni F, Darmon E, Poon WCK, Leach DRF. Overexpression of the single-stranded DNA-binding protein (SSB) stabilises CAG*CTG triplet repeats in an orientation dependent manner. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(1):153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.López de Saro FJ, Marinus MG, Modrich P, O’Donnell M. The beta sliding clamp binds to multiple sites within MutL and MutS. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(20):14340–14349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons LA, Davies BW, Grossman AD, Walker GC. Beta clamp directs localization of mismatch repair in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Cell. 2008;29(3):291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feulner G, et al. Structure of the rhsA locus from Escherichia coli K-12 and comparison of rhsA with other members of the rhs multigene family. J Bacteriol. 1990;172(1):446–456. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.446-456.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards RA, Keller LH, Schifferli DM. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene. 1998;207(2):149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minet AD, Rubin BP, Tucker RP, Baumgartner S, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Teneurin-1, a vertebrate homologue of the Drosophila pair-rule gene ten-m, is a neuronal protein with a novel type of heparin-binding domain. J Cell Sci. 1999;112 (Pt 1):2019–2032. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.12.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aggarwal K, Lee KH. Overexpression of cloned RhsA sequences perturbs the cellular translational machinery in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(18):4869–4880. doi: 10.1128/JB.05061-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. DNA mismatch repair. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kadyrov FA, Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Modrich P. Endonucleolytic function of MutLalpha in human mismatch repair. Cell. 2006;126(2):297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghodgaonkar MM, et al. Ribonucleotides misincorporated into DNA act as strand-discrimination signals in eukaryotic mismatch repair. Mol Cell. 2013;50(3):323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lujan SA, Williams JS, Clausen AR, Clark AB, Kunkel TA. Ribonucleotides are signals for mismatch repair of leading-strand replication errors. Mol Cell. 2013;50(3):437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song L, Yuan F, Zhang Y. Does a helicase activity help mismatch repair in eukaryotes? IUBMB Life. 2010;62(7):548–553. doi: 10.1002/iub.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Genschel J, Bazemore LR, Modrich P. Human exonuclease I is required for 5′ and 3′ mismatch repair. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(15):13302–13311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kadyrov FA, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutLalpha is a mismatch repair endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(51):37181–37190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tran HT, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. The 3′-->5′ exonucleases of DNA polymerases delta and epsilon and the 5′-->3′ exonuclease Exo1 have major roles in postreplication mutation avoidance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(3):2000–2007. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flores-Rozas H, Clark D, Kolodner RD. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen and Msh2p-Msh6p interact to form an active mispair recognition complex. Nat Genet. 2000;26(3):375–378. doi: 10.1038/81708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kleczkowska HE, Marra G, Lettieri T, Jiricny J. hMSH3 and hMSH6 interact with PCNA and colocalize with it to replication foci. Genes Dev. 2001;15(6):724–736. doi: 10.1101/gad.191201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merlin C, McAteer S, Masters M. Tools for characterization of Escherichia coli genes of unknown function. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(16):4573–4581. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4573-4581.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spell RM, Jinks-Robertson S. Determination of mitotic recombination rates by fluctuation analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;262:3–12. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-761-0:003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]