Significance

Understanding land-surface biophysical feedbacks to the atmosphere is needed if we are to simulate regional climate accurately. In the Arctic, previous studies have shown that enhanced vegetation growth decreases albedo and amplifies warming. In contrast, on the Tibetan Plateau, a statistical model based on in situ observations and decomposition of the surface energy budget suggests that increased vegetation activity may attenuate daytime warming by enhancing evapotranspiration (ET), a cooling process. A regional climate model also simulates daytime cooling when prescribed with increased vegetation activity, but with a magnitude smaller than observed, likely because this model simulates weaker ET enhancement in response to increased vegetation growth.

Keywords: climate change, feedback, evapotranspiration, vegetation, Tibetan Plateau

Abstract

In the Arctic, climate warming enhances vegetation activity by extending the length of the growing season and intensifying maximum rates of productivity. In turn, increased vegetation productivity reduces albedo, which causes a positive feedback on temperature. Over the Tibetan Plateau (TP), regional vegetation greening has also been observed in response to recent warming. Here, we show that in contrast to arctic regions, increased growing season vegetation activity over the TP may have attenuated surface warming. This negative feedback on growing season vegetation temperature is attributed to enhanced evapotranspiration (ET). The extra energy available at the surface, which results from lower albedo, is efficiently dissipated by evaporative cooling. The net effect is a decrease in daily maximum temperature and the diurnal temperature range, which is supported by statistical analyses of in situ observations and by decomposition of the surface energy budget. A daytime cooling effect from increased vegetation activity is also modeled from a set of regional weather research and forecasting (WRF) mesoscale model simulations, but with a magnitude smaller than observed, likely because the WRF model simulates a weaker ET enhancement. Our results suggest that actions to restore native grasslands in degraded areas, roughly one-third of the plateau, will both facilitate a sustainable ecological development in this region and have local climate cobenefits. More accurate simulations of the biophysical coupling between the land surface and the atmosphere are needed to help understand regional climate change over the TP, and possible larger scale feedbacks between climate in the TP and the Asian monsoon system.

The Tibetan Plateau (TP) plays a key role in the Asian summer monsoon, a weather system affecting more than half of the world’s population. The TP has experienced a pronounced warming over recent decades (1), with a warming rate of about twice the global average for the period 1960–2009 (2, 3), yet with heterogeneous patterns. Both observations and model studies show that recent climate change has had an impact on the structure and ecological functioning of TP grasslands (4–7). One robust observation is that temperature has increased more slowly during the day than during the night, thereby reducing the diurnal temperature range by about 0.23 °C per decade over the period 1961–2003 (8). Understanding the mechanisms driving the spatiotemporal patterns of temperature change over the TP is critical for the development of adaptation strategies to protect its vulnerable grassland ecosystems and for better understanding the coupling between regional changes over the TP and the larger Asian monsoon system (9).

Changes in vegetation albedo, emissivity, and evapotranspiration (ET) altogether exert feedbacks on climate (10–14). In the Arctic, it has been shown that a temperature-driven increase of vegetation productivity can produce a positive feedback to warming through reduced albedo, which increases the amount of solar radiation absorbed by the surface (11, 14, 15). However, such a positive albedo feedback may be partially offset by increased cooling from higher ET (16–18). The balance between these two biophysical mechanisms of opposite sign in the surface energy budget likely determines how vegetation changes affect local climate, but little observational evidence exists to demonstrate vegetation feedbacks on climate at regional or continental scales (19, 20). For the TP, it is as yet unknown whether the vegetation changes may have contributed to local temperature variations. The goal of this study is to investigate how changes in vegetation greenness exert influences on local temperature. To that end, we have used satellite-measured vegetation greenness, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), as a proxy of vegetation activity (photosynthesis and vegetation coverage), in combination with in situ air temperature observations and three independent gridded ET estimates, one based on the Penman–Monteith equation and Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) land products (ETM), the second based on the Priestley and Taylor equation [Global Land Surface Evaporation: the Amsterdam Methodology (GLEAM); ETG], and the third from a machine-learning algorithm that interpolates flux-tower ET measurements in time and space (ETJ). A sensitivity analysis of the ET cooling effect based on intrinsic biophysical mechanisms and simulations from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) regional climate model (Methods) are used as well.

Results

Relationships Between Greening and Temperature Trends.

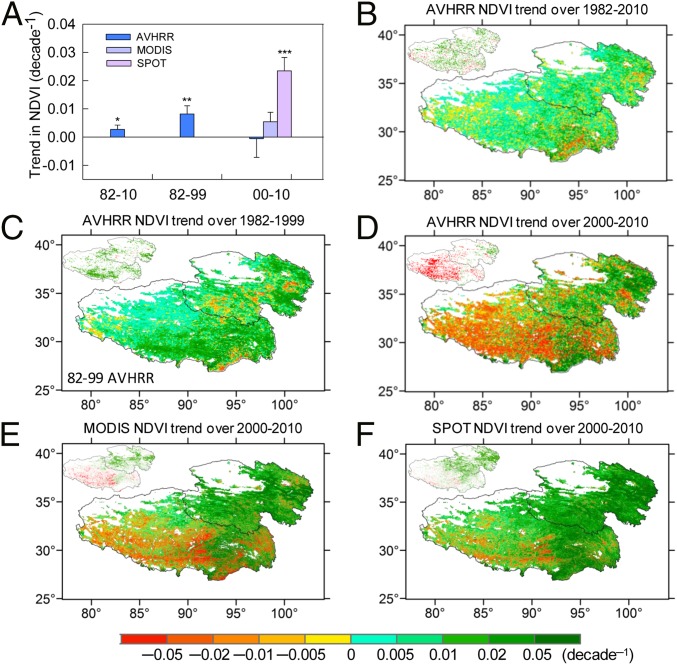

We first characterize changes in the growing season (May to September) NDVI using three different satellite-derived NDVI datasets: one from an Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR; 1982–2010) and two others from a MODIS (2000–2010) and Système Pour l’Observation de la Terre (SPOT)-VEGETATION (2000–2010) (Methods). The AVHRR NDVI data show a positive trend (i.e., greening) during the entire period 1982–2010 (Fig. 1 A and B). Consistent with an earlier study (21), the greening trend of the AVHRR NDVI over the TP mainly occurred during the 1980s and 1990s (Fig. 1 A and C). During their period of overlap in the 2000s, the three NDVI datasets (Fig. 1A) exhibit similar spatial patterns of the trends (Fig. 1 D–F) but different mean trends when averaged over the entire TP area (Fig. 1A). All three datasets show a systematic decrease in the growing season NDVI over the past decade in the southwest of the plateau. This decrease is associated with a delayed vegetation green-up date (22). In contrast, greening persisted over the northeast of the TP.

Fig. 1.

Changes in the growing season (May–September) NDVI across the TP over the past three decades. (A) Trend in the growing season NDVI at a regional scale over 1982–2010, 1982–1999, and 2000–2010. The pixels with growing season NDVI lower than 0.10 are not considered. ***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; *P < 0.10. Trends with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10). (B–F) Spatial distribution of the growing season NDVI trend for the different datasets and periods. (Insets) Pixels with significantly (P < 0.05) negative (red) or positive (green) trends are shown in each map.

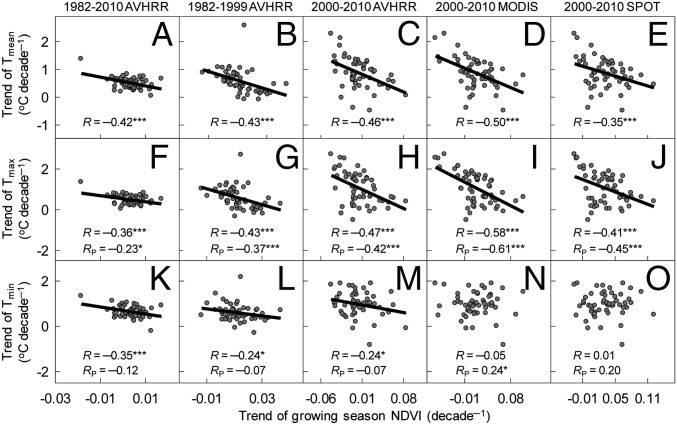

We hypothesize that through mechanisms of land surface feedback, spatial differences in temporal trend of the NDVI (NDVItrend) across the TP region (Fig. 1 B–F) affect regional patterns of surface temperature trend. To test this hypothesis, we first investigated the spatial relationship between observed NDVItrend and the temporal trend (Tmean,trend) of growing season average of daily mean temperature (Tmean) from 55 meteorological stations. Because vegetation growth over the TP is limited by low temperature (Fig. S1), in the absence of feedbacks, one would expect a positive spatial correlation between Tmean,trend and NDVItrend. However, when NDVItrend is regressed against the meteorological station Tmean,trend, it is found that the correlation is negative (P < 0.01). This relationship remains robust regardless of the choice of NDVI dataset (Fig. 2 A–E), suggesting that increasing vegetation activity may exert a negative forcing (cooling) on local temperature trends.

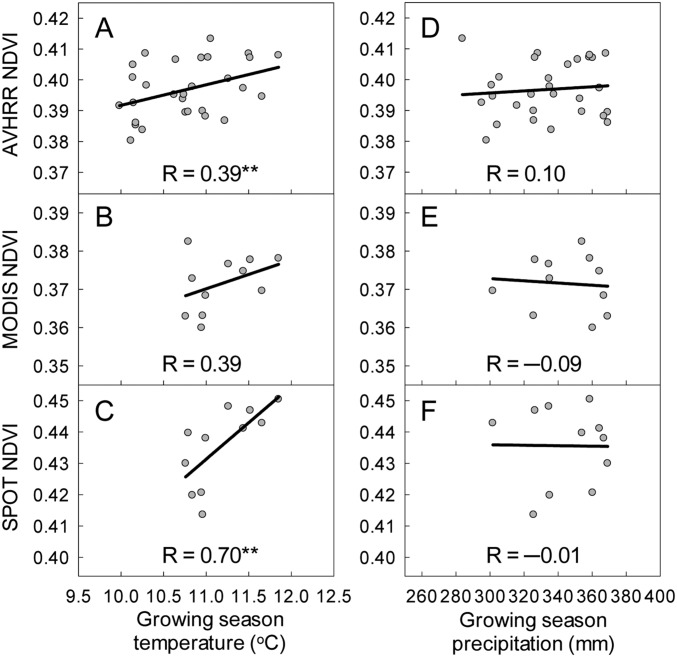

Fig. S1.

Interannual relationships of an average growing season NDVI over 55 meteorological stations and the corresponding growing season temperature (A–C) and precipitation (D–F). Note that the NDVI is not significantly related to precipitation. ***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; *P < 0.10. Correlations with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10).

Fig. 2.

Spatial relationship of the growing season NDVI trend with trend of Tmean, Tmax, and Tmin across the 55 meteorological stations in the TP. In each of the panels (A–O), the period for calculating the temporal trends and NDVI dataset are given in the top of the figure. Each point is for one station. R is the correlation coefficient between the trend of the growing season NDVI and the trend of temperature. RP indicates partial correlation coefficients of the trend of the growing season NDVI with the trend of Tmax (or Tmin) through controlling Tmin (or Tmax). ***P < 0.01; *P < 0.10. Correlations with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10).

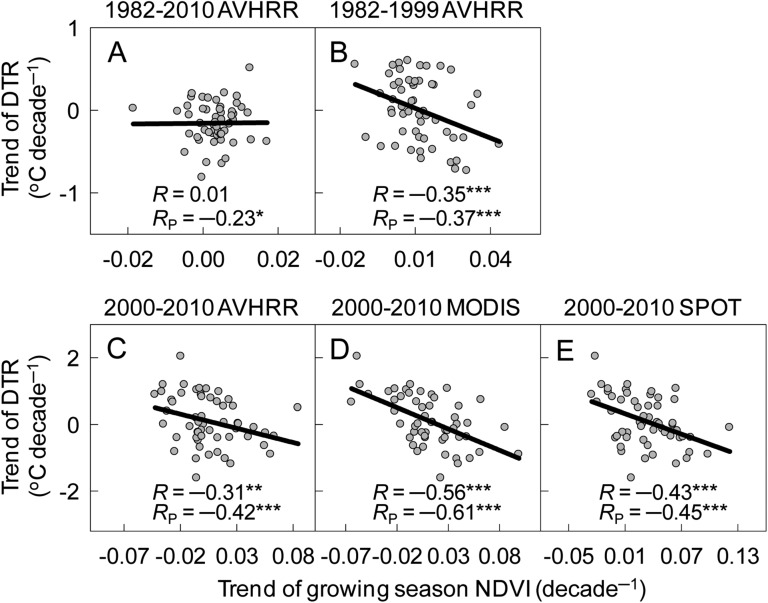

Because changes in vegetation activity have asymmetrical effects on the diurnal cycle of surface air temperature (13), we examine the statistical relationships between NDVItrend and Tmax,trend which is the trend in daytime maximum temperature (Tmax) and Tmin,trend which is the trend in nighttime minimum temperature (Tmin). NDVItrend is found to have a stronger negative spatial correlation with Tmax,trend rather than with Tmin,trend (Fig. 2 F–O). NDVItrend from MODIS and SPOT is not significantly (Fig. 2 N and O) correlated with Tmin,trend across the 55 meteorological stations. Further, NDVItrend does not show significantly negative correlations with Tmin,trend when the confounding effects of Tmax are statistically removed (Fig. 2 K–O). In contrast, accounting for the confounding effect of Tmin on Tmax does not affect the significantly negative correlation between NDVItrend and Tmax,trend (Fig. 2 F–J), suggesting that increasing vegetation activity may exert a cooling effect on local temperature trends, primarily in the daytime.

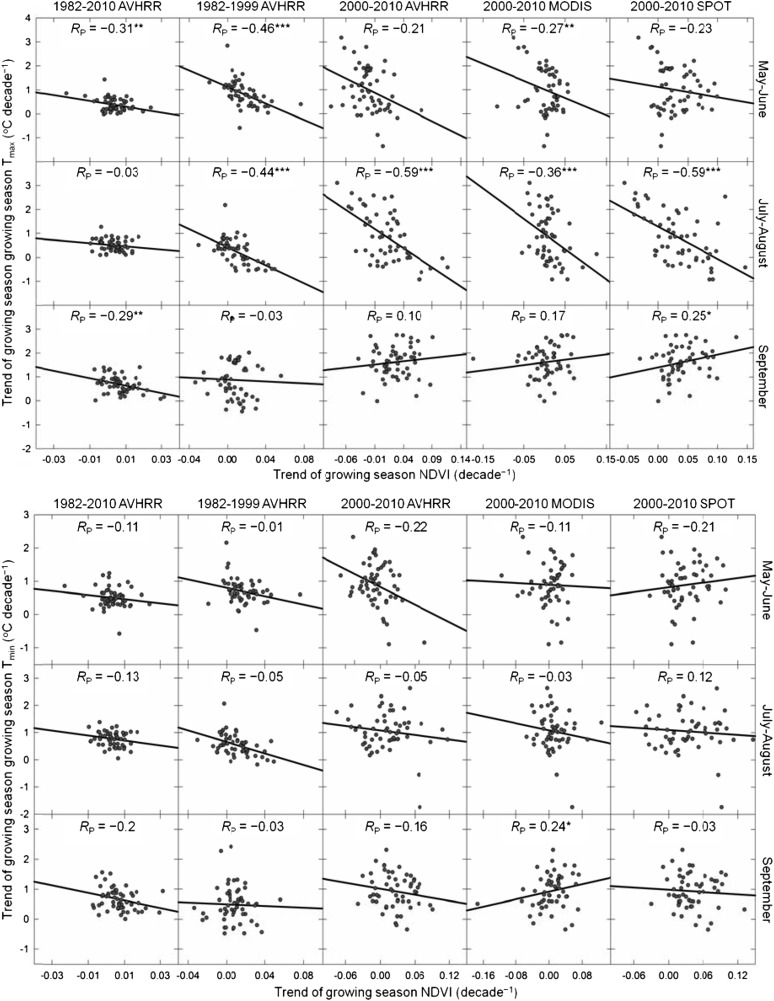

The spatially negative correlation between NDVItrend and Tmax,trend across the TP is expected to be stronger in summer when vegetation is more active and radiation is more intense. We did find a stronger negative correlation between Tmax,trend and NDVItrend for summer (July and August) than for spring (May and June) or for fall (September) (Fig. S2). In contrast, Tmin,trend consistently shows no significantly negative correlation with NDVItrend for all cases. Because of this nonsymmetrical effect of greening on Tmax and Tmin, the trend in diurnal temperature range is negatively correlated with NDVItrend (P < 0.01; Fig. S3 B–E), except for the period 1982–2010, during which the correlation is only marginally significant (P = 0.07; Fig. S3A).

Fig. S2.

Spatial relationship of the NDVI trend with the trend of Tmean, Tmax, and Tmin in different seasons across the 55 meteorological stations on the TP. RP indicates partial correlation coefficients of the trend of the growing season NDVI with the trend of Tmax (or Tmin) through controlling Tmin (or Tmax). ***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; *P < 0.10. Correlations with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10).

Fig. S3.

Spatial relationship of the growing season NDVI trend with the trend of diurnal temperature range (DTR) across the 55 meteorological stations on the TP. In each of panels (A–E), the period for calculating the temporal trends and NDVI data set are given in the top of the panel. R indicates the correlation coefficient between the trend of the growing season NDVI and the DTR trend. RP indicates partial correlation coefficients of the trend of the growing season NDVI with the DTR trend through controlling Tmin. ***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; *P < 0.10. Correlations with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10).

Possible Mechanisms.

The significant negative correlation between NDVItrend and Tmax,trend suggests an ET-induced cooling effect in the daytime. ET is a key process that dissipates the energy absorbed by the vegetation and determines the diurnal cycle of near-surface air temperature. The cooling feedback due to increased ET in response to the positive trend of vegetation greenness is expected to reduce daytime (Tmax) rather than nighttime (Tmin) warming rates, and to have stronger impacts in the summer than in other seasons. This mechanism is consistent with evidence from the spatial patterns of observations. Next, we use statistical and numerical tools, as well as a sensitivity analysis, to investigate this mechanism further.

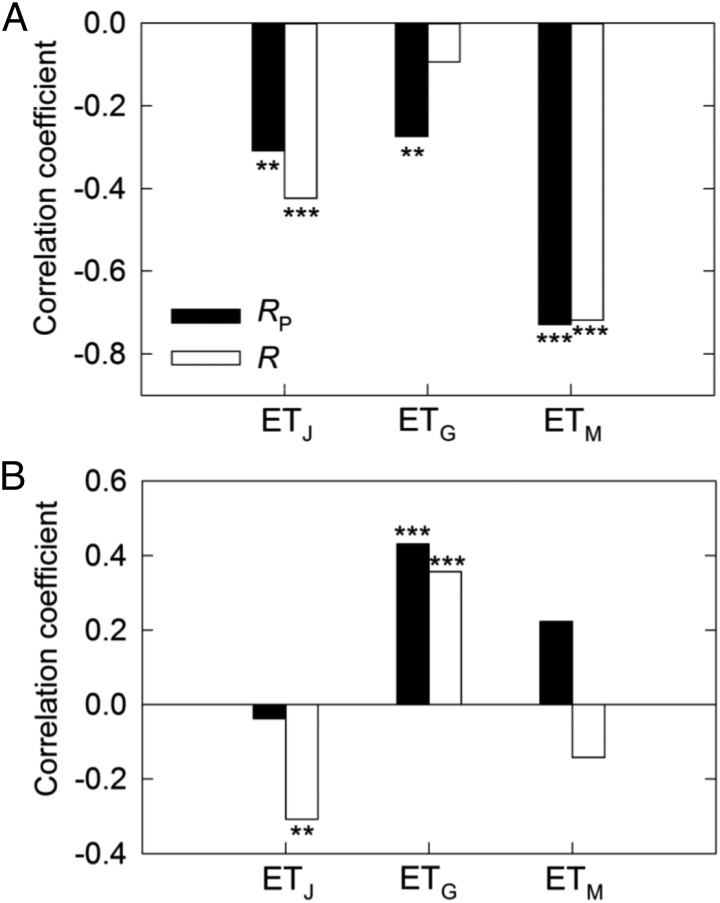

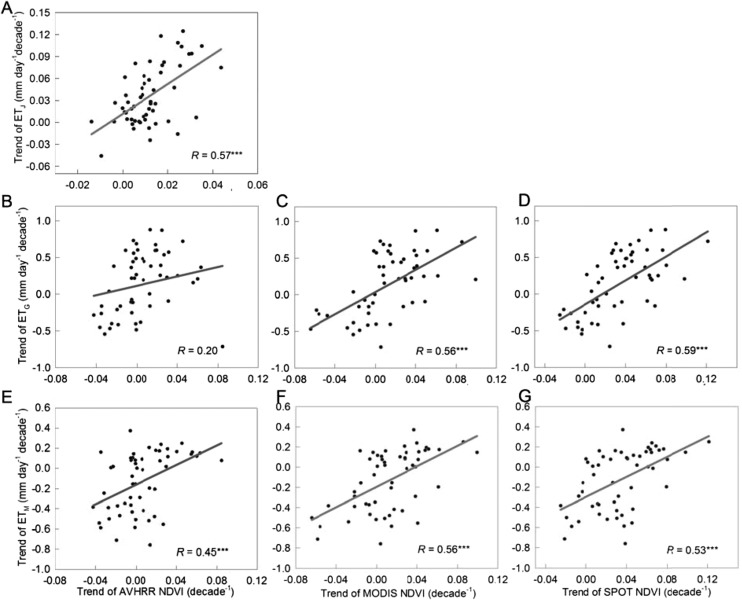

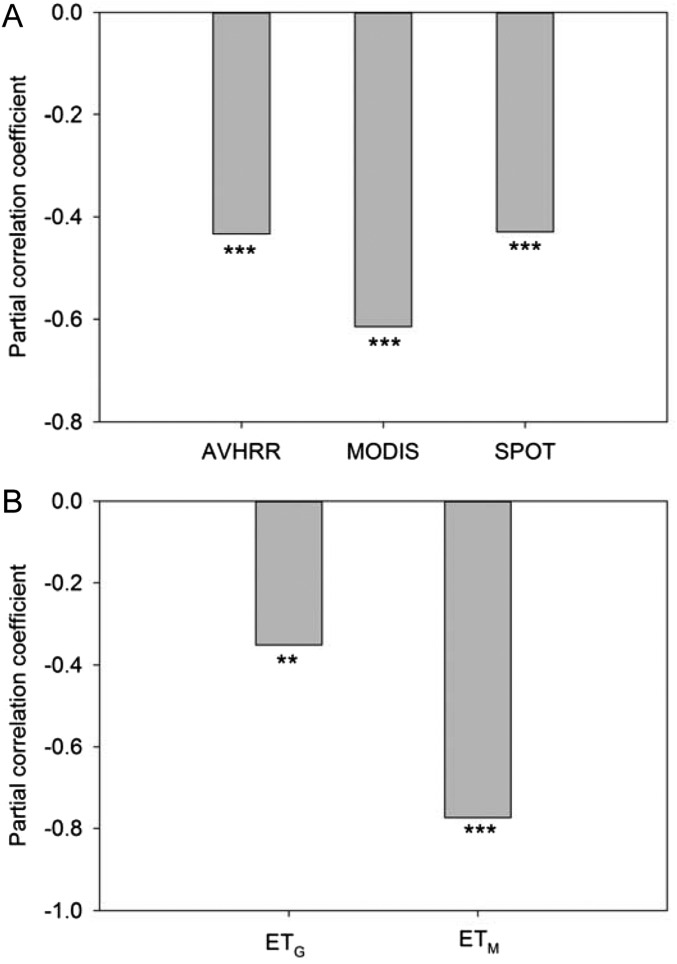

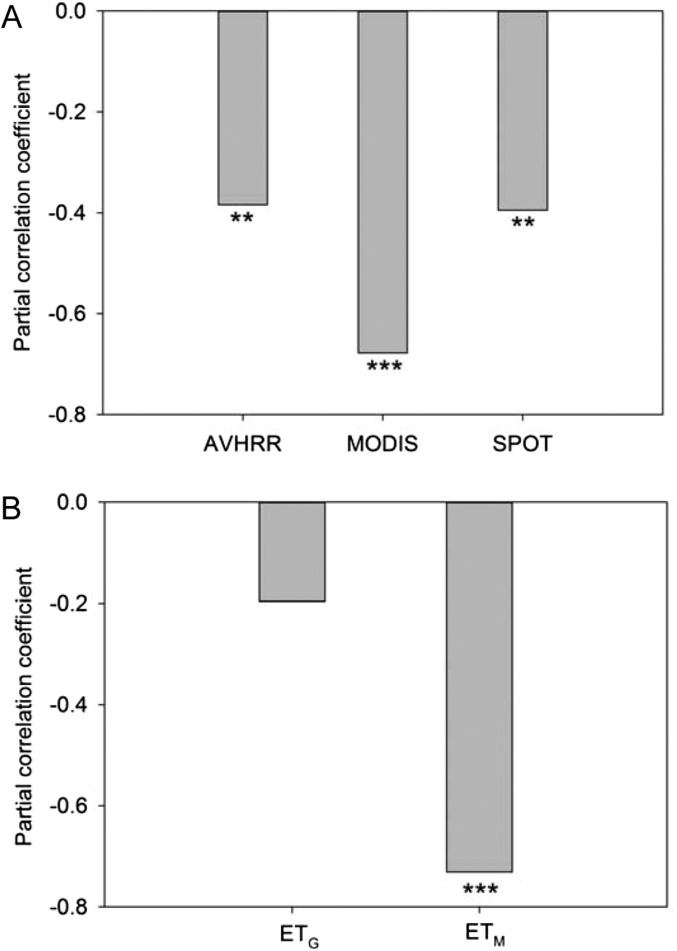

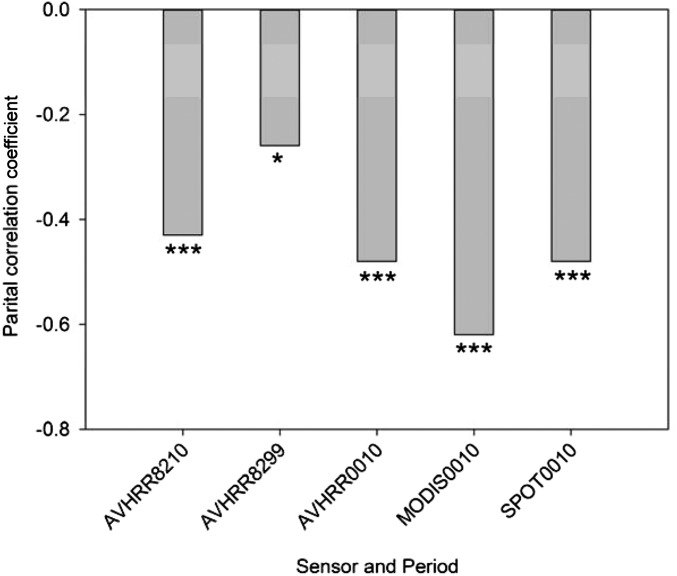

We first examine the spatial correlations between in situ Tmax,trend and the temporal trend in ET (ETtrend) from (i) ETM products (MOD16A2-ET) for the period 2000–2010 (23), (ii) ETG products over the period 2000–2010 (24), and (iii) ETJ products (25) over the period 1982–1999 (data descriptions are provided in Methods). For all three ET datasets, the spatial patterns of ETtrend are found to be negatively correlated with Tmax,trend (P < 0.05; Fig. 3A). In contrast, the patterns of Tmin,trend are not significantly correlated with ETtrend (from partial correlation, P > 0.10; Fig. 3B). In addition, the spatial pattern of ETtrend is significantly and positively correlated with NDVItrend for the three satellite NDVI datasets (P < 0.10 for GLEAM ETtrend and AVHRR NDVItrend and P < 0.01 for the other combinations of ETtrend and NDVItrend; Fig. S4). Moreover, the negative correlations between Tmax,trend and ETtrend (or NDVItrend) still hold when we statistically account for the trends of both Tmin and albedo (or absorbed solar radiation) (Figs. S5 and S6). These results suggest that greening increases ET, which, in turn, cools Tmax.

Fig. 3.

Coefficient of the spatial correlation between growing season ET trend and Tmax (A) and Tmin (B) across the TP. R is the correlation coefficient. RP is the partial correlation coefficient of the trend of growing season ET with the trend of Tmax (or Tmin) removing the effects of Tmin (or Tmax). ET was extracted from a dataset produced by a machine-learning algorithm using flux-tower measurements over 1982–1999 (ETJ) and ETM (MOD16A2-ET) and ETG products over 2000–2010. ***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05. Correlations with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10).

Fig. S4.

Spatial correlations between the trend of the growing season ET and the trend of the growing season NDVI. (A) Trend over 1982–1999 using ET estimated in the machine-learning algorithm (ETJ) and AVHRR NDVI. (B–D) Trend over 2000–2010 using the ETG and NDVI derived from the AVHRR, MODIS, and SPOT, respectively. (E–G) Same as B–D, but for ETM (MOD16A2). ***P < 0.01; *P < 0.10.

Fig. S5.

Spatial partial correlation between the Tmax trend and NDVI trend (A, or ET trend in B), controlling the Tmin trend and MODIS albedo trend. Trends are for the period 2000–2010. The horizontal axis label shows the sensor for the NDVI. ***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05.

Fig. S6.

Spatial partial correlation between the Tmax trend and NDVItrend (A) and ET trend (B), controlling trends of absorbed solar radiation [Rshort (1 − α)] and Tmin. ***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05. Correlations with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10). Trends are for the period 2000–2006 due to the lack of short-wave radiation data since 2007. The horizontal axis label shows the sensor or satellite for the NDVI. Note that the ETG may contain large uncertainty because it used the tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) precipitation (product code 3B42RT) that was biased on the TP (51, 52).

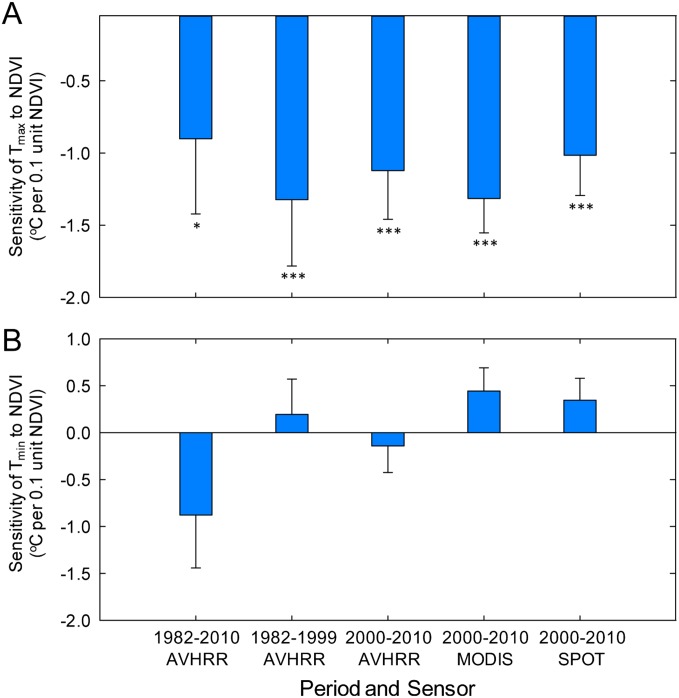

To quantify the effect of vegetation greenness on temperature, we perform a multiple linear regression analysis in which Tmax,trend is set as the dependent variable and NDVItrend and Tmin,trend are set as independent variables. This procedure can eliminate the influence from the relationship between Tmax,trend and Tmin,trend, and it defines the linear regression slope of NDVItrend to Tmax,trend as the sensitivity of Tmax,trend to NDVItrend. Different values of the regression slope are found for different decades and different satellite datasets, but the sign of the slopes always indicates a lower Tmax,trend where the NDVI has increased, which is consistent with the expectation that greening cools near-surface air temperature. These slopes range from −0.9 ± 0.5 °C to −1.3 ± 0.2 °C in response to an NDVI increase of 0.1 (Fig. S7A). Note that the NDVI is dimensionless and that an increase of 0.1 is comparable to the greatest NDVItrend in one decade, as shown in Fig. 2 C–E.

Fig. S7.

Sensitivity of Tmax (A) and Tmin (B) to the growing season NDVI change, determined through spatial multiple linear regression in which the trend of Tmax (Tmin) was set as the dependent variable and the trends of the NDVI and Tmax were set as the independent variables over the 55 climate stations. ***P < 0.01; *P < 0.10. Regression coefficients with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10).

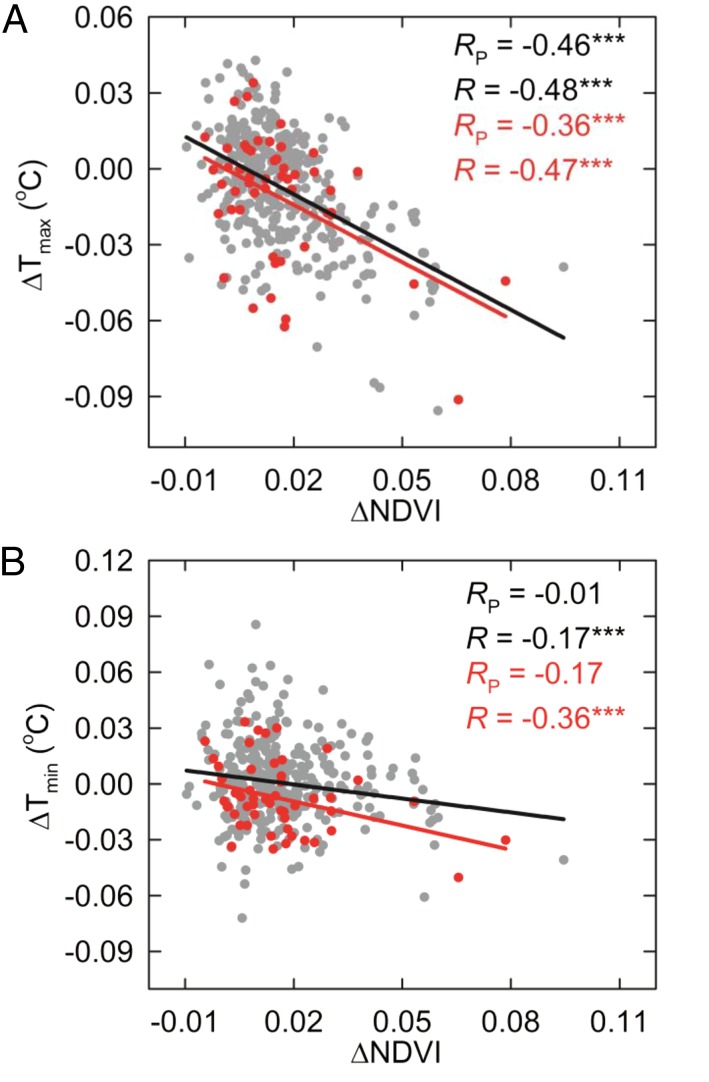

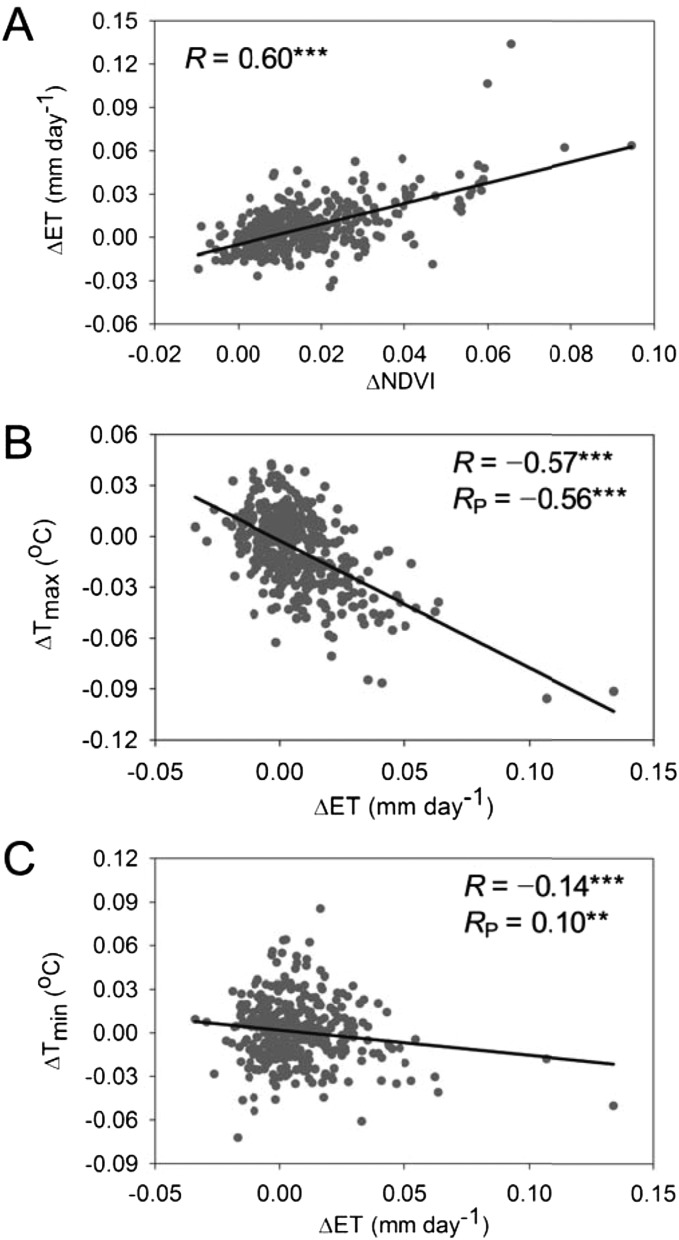

Next, we use the WRF, version 3.2 (WRF3.2) regional climate model (26) with the Noah land surface scheme (27) to simulate the magnitude of vegetation-to-temperature effects over the TP. Two simulations were performed: one without (S1) and one with (S2) prescribed day-to-day changes in growing season leaf area index (LAI) from AVHRR NDVI observations during the period 1982–2010 (Methods). The difference between S2 and S1 allows us to quantify the effect of greenness changes on surface air temperature. As shown in Fig. 4, the average S2−S1 difference of prescribed NDVI (ΔNDVI; used to define the LAI difference prescribed in WRF3.2) is spatially significantly (P < 0.01) and negatively correlated with the S2−S1 difference of modeled Tmax (ΔTmax). Unlike the observation-based statistical analysis, which cannot separate forcing and feedbacks, the WRF simulations can quantify the feedbacks. The spatial correlation between ΔNDVI and simulated ΔTmax is stronger than the spatial correlation between ΔNDVI and the difference of modeled Tmin (ΔTmin). Consistent with the observational analysis (Fig. S4), a significant and positive relationship is also found between ΔNDVI and the S2−S1 ET difference (ΔET), given by the Noah land surface model (27) in WRF3.2 (P < 0.01; Fig. S8A). In the WRF3.2 simulations, ΔET shows stronger spatial correlations with ΔTmax than with ΔTmin (Fig. S8 B and C), which supports the proposed mechanism of an evaporative cooling feedback whereby increased vegetation LAI reduces daytime air temperature over the TP region. However, the sensitivity of Tmax to the prescribed LAI change (from the observed NDVI change) in WRF3.2 is much smaller than the sensitivity of Tmax derived from the statistical analyses of long-term observations. The WRF3.2 simulations show that an increase in the NDVI by 0.1 results in a cooling of Tmax by only 0.07 ± 0.01 °C (P < 0.01), which is merely 10% of the sensitivity of Tmax to the NDVI diagnosed from observations (Fig. S7A).

Fig. 4.

Spatial statistical relationships between the temperature difference from two simulations of the WRF3.2-Noah regional climate model (S2−S1) and the growing season NDVI difference (ΔNDVI) prescribed in these simulations. In simulation S1, the LAI of the land surface model Noah is prescribed from the climatological NDVI. In simulation S2, the variable LAI from the observed LAI is prescribed. The difference between S2 and S1 gives the modeled effect of an increased NDVI on the regional climate daytime temperature difference (A; ΔTmax) and nighttime temperature difference (B; ΔTmin). ΔNDVI, ΔTmax, and ΔTmin are estimated as the differences in the 29-y averaged values of the growing season NDVI, Tmax, and Tmin between the S2 and S1 simulations, respectively. The red circles indicate the spatial correlations using the grids where meteorological stations are located and the gray and red ones altogether indicate all the grids. R is the correlation coefficient between the trend of the growing season NDVI and the trends in Tmax or Tmin. RP indicates partial correlation coefficients of the trend of the growing season NDVI with the trend in Tmax (or Tmin) through controlling Tmin (or Tmax). ***P < 0.01. Correlations with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10).

Fig. S8.

Spatial correlations between the ΔET of the WRF model and ΔNDVI (A), ΔTmax (B), and ΔTmin (C), respectively. Two simulations were performed using the WRF3.2 regional climate model: one without (S1 simulation) and one with (S2 simulation) changes in LAI derived from the AVHRR NDVI during 1982–2010 (Methods). ΔNDVI, ΔTmax, ΔTmin, and ΔET are the differences in the 29-y averaged values of the growing season NDVI, Tmax, Tmin, and ΔET between S2 and S1 simulations, respectively. ***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05.

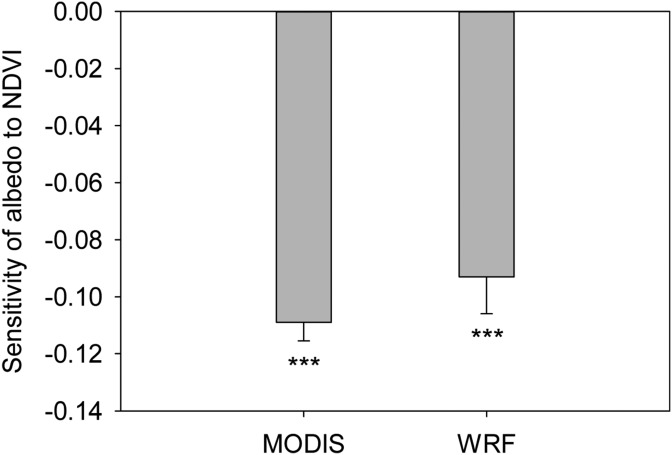

To investigate why the model estimates of the biophysical cooling effect are smaller than observations, we examined whether the Noah land surface model of WRF3.2 realistically simulates changes in albedo. We first compared the modeled albedo with MODIS white sky albedo in the short-wave band (28). The simulated sensitivity of albedo to the NDVI (−0.09 ± 0.01) in WRF3.2 is close to the sensitivity of MODIS albedo to NDVI (−0.11 ± 0.01) as obtained from a spatial data regression analysis (Fig. S9). This comparison indicates that the smaller cooling effect in WRF3.2 could not be attributed to the model albedo biases. We then compared the sensitivity of ET to the NDVI in both WRF3.2 simulations and in the observations. Linear spatial regression between the S2−S1 ΔNDVI and the S2−S1 ΔET showed that a 0.1-unit increase in growing season NDVI is associated with an increase of ET by only 0.07 ± 0.01 mm⋅d−1 in WRF3.2 (Fig. S10). In contrast, the spatial ET sensitivity to the NDVI in the observations is 0.49 ± 0.13 mm⋅d−1, and ranges from 0.20 ± 0.04 to 0.51 ± 0.10 mm⋅d−1 among different ET and NDVI datasets (Fig. S10). Therefore, the weaker ET cooling feedback likely results from the lower ET sensitivity to greenness in WRF3.2. We also found that the ET trend of WRF3.2 in S2 differs considerably from the observed ET trend (Fig. S11), indicating that the temporal ET trend is not correctly reproduced in the WRF S2 simulations. In WRF3.2, the sensitivity of simulated ET to the NDVI depends on the land surface model used (28), suggesting the need to improve the model parameterizations considering the specific biophysical characteristics of TP grassland vegetation (29). Compared with regions in the same latitude band, the TP is characterized by a combination of high radiation and low temperatures, as well as by complex soil water variability (30); these properties are difficult to reproduce in a land-surface model. WRF3.2 may also have systematic biases in modeling other ET-relevant processes, such as radiative transfer, boundary-layer dynamics, and cloud physics. Future climate simulations of the TP thus require more observations to improve the parameterization and calibration of ET.

Fig. S9.

Comparison of MODIS and WRF (S2 simulation) model-derived effect of change in vegetation growth on the albedo in the TP. The effect of change in vegetation growth on the albedo was estimated as the coefficient of the NDVI in spatial linear regression between the mean growing season albedo over 2003–2010 and the AVHRR NDVI across the TP. The product coded as MCD43C3 (collection 5) was used to extract the white sky albedo over the short-wave range. ***P < 0.01.

Fig. S10.

Comparison of the effect of changes in vegetation growth on ET between WRF model simulations and observation-based estimates for the TP. In WRF model simulations, the effect of change in vegetation growth on the ET was estimated as the coefficient of ΔNDVI (S2−S1) in the spatial linear regression between the growing season ΔET and ΔNDVI. The observation-based estimates of the effect of change in vegetation growth on the ET were derived from a similar regression but using growing season trends over 2000–2010 for both the ETM and ETG and each of the AVHRR, MODIS, and SPOT NDVIs, and over 1982–1999 of the machine-learning algorithm based ET (ETJ) and AVHRR NDVI. ***P < 0.01. Regression coefficients with no asterisk are not significant (P > 0.10).

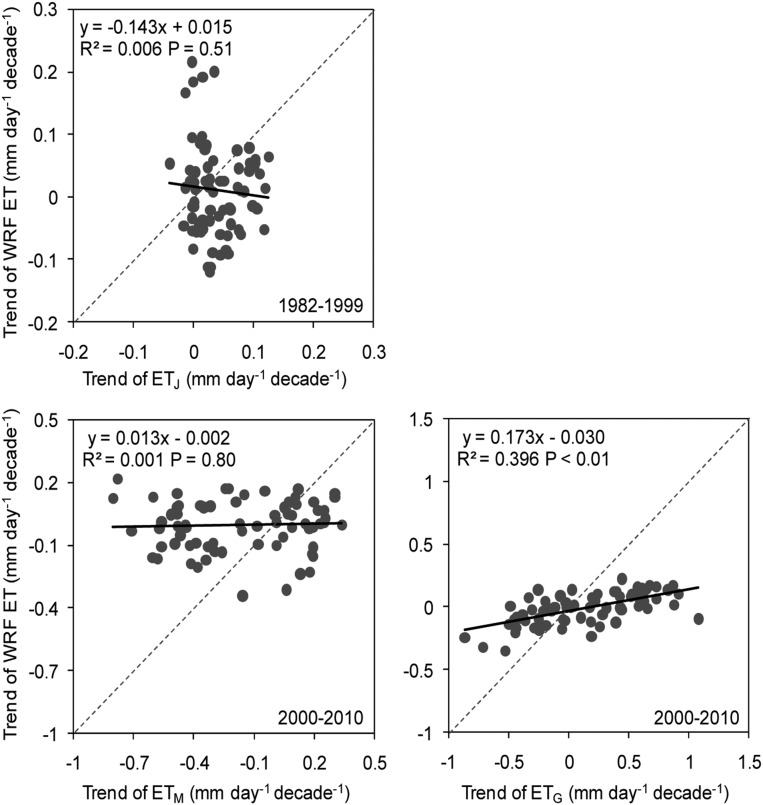

Fig. S11.

Spatial relationship between WRF model S2 ET trend and observed ET trends over 1982–1999 using the ETJ (25) and over 2000–2010 using the ETM (23) and ETG (24).

Given model imperfections in simulating ET over the TP, we used a sensitivity analysis based on intrinsic biophysical mechanisms to estimate how much daytime surface temperature (Ts) can change for an NDVI increase of 0.1. It is assumed that two adjacent blocks of grassland share the same background climate state and have no horizontal flow between them. The only difference is that one block has an NDVI value 0.1 greater than the other. This increase in the NDVI by 0.1 could enhance ET by ∼0.5 mm⋅d−1 and decrease albedo by 0.01 (Figs. S9 and S10). In accordance with a study by Lee et al. (18), the resulting difference in Ts is estimated as −0.76 °C (Sensitivity Analysis Based on Intrinsic Biophysical Mechanisms), which is within the range statistically estimated from observations (Fig. S7). The change of Ts can be further divided into two components, a warming of 0.16 °C due to the decreased albedo and a cooling of 0.92 °C due to the increased ET for an NDVI difference of 0.1 between a pair of grasslands under the same background climate (Sensitivity Analysis Based on Intrinsic Biophysical Mechanisms).

In addition to ET and albedo, other factors, such as changes in large-scale circulation and stratospheric ozone depletion, could modify surface energy budgets and the spatial patterns of the trend of air temperature over the TP. Our statistical analysis also suggests that the negative spatial correlation between Tmax,trend and NDVItrend is unlikely to be caused by the changes in large-scale flows (Impacts of Large-Scale Flows and Stratospheric Ozone Depletion and Fig. S12). In addition, there is no evidence indicating that large-scale flows directly affect the spatial pattern of temperature trend within the TP (31). Stratospheric ozone depletion has been hypothesized to contribute a larger warming over the northern plateau during the past few decades (32) but cannot explain the negative Tmax,trend/NDVItrend correlation (Impacts of Large-Scale Flows and Stratospheric Ozone Depletion). In addition, the insignificance of the Tmin,trend/NDVItrend correlation could result from other factors because the nocturnal boundary layer is more sensitive to energy/turbulence changes (13).

Fig. S12.

Partial correlation analysis between the Tmax trend and the NDVItrend across the weather stations, setting the Tmin trend, latitude, and longitude as the controlling variables. ***P < 0.01; *P < 0.10. The horizontal axis labels indicate the sensor for the NDVI and the period of trend.

Sensitivity Analysis Based on Intrinsic Biophysical Mechanisms

We used a sensitivity analysis to estimate the magnitude of greening on daytime TS, when there is no horizontal flow. We assume that two adjacent blocks of grassland share the same background climate state (18). The only difference between them is that the NDVI of one block is 0.1 higher than the other. According to Lee et al. (18), ΔTS, the difference in surface temperature between them is

where is an energy redistribution factor, and λ0 = 1/(4σTs3) is the temperature sensitivity resulting from the long-wave radiation feedback. All variable names are defined below.

In the first term on the right-hand side, ΔS = Δα × Rshort, where α and Rshort are short-wave albedo and incident short-wave radiation, respectively. Thus ΔS is the change in absorbed short-wave radiation due to the albedo variation, and the first term on the right refers to the surface temperature change due to the albedo variation (resulting from the NDVI variation in our study). According to the observations, an increase in the NDVI of 0.1 results in an albedo decrease of 0.01.

The second item on the right-hand side refers to the surface temperature change caused by change in roughness:

where Δra is the change in aerodynamic resistance. We neglect the second term because the alpine steppe or meadows on the TP are dwarf and homogeneous; a difference in the NDVI of 0.1 should lead to only a small change in ra (46).

The third term on the right-hand side represents the changes in surface temperature caused by the change in Bowen ratio (Δβ):

According to the observation-based analyses, an increase in the NDVI by 0.1 corresponds to an ET increase of 0.5 mm⋅d−1. For the case of a multiple-year average, we assume an increase of ET by ΔET would result in a decrease in sensible heat flux of the same magnitude. Using the following parameter settings, an NDVI increase of 0.1 (an ET increase of 0.5 mm⋅d−1 and an albedo decrease of 0.01; Figs. S9 and S10) could cause a decrease in Ts of 0.76 °C. Here ΔTs is 0.16 °C due to the albedo decrease and −0.92 °C due to the ET increase. The magnitude of −0.76 °C per 0.1 NDVI change is close to the one obtained in the observation-based analysis. We further performed a similar sensitivity analysis but used the WRF-derived ET (0.07 mm⋅d−1 per 0.1 NDVI) and albedo sensitivity to the NDVI (0.009 per 0.1 NDVI). Corresponding to an NDVI increase of 0.1, the surface temperature is 0.02 °C higher, which results from a cooling of −0.12 °C due to the increased ET and a warming of 0.14 °C due to the decrease in albedo. This result suggests that the lower Tmax sensitivity to greening in the WRF model could be caused by an underestimation of ET enhancement.

The parameters used are as follows:

Stefan–Boltzmann constant: σ = 5.67 × 10−8 W⋅m−2⋅K−4

Air density: ρ = 0.685 kg⋅m−3, at 18 °C (growing season MODIS land surface temperature (LST) averaged for 2000–2010), 4,500 m above sea level, 40% relative humidity

Specific heat of air at constant pressure: Cp = 1,004 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1 (47)

Aerodynamic resistance: ra = 70 s⋅m−1 (47)

TS = 291 K (growing season MODIS LST averaged for 2000–2010), so λ0 = 0.17 K⋅W⋅m−2

Incident short-wave radiation: 500 W⋅m−2, approximate value is provided by Tang et al. (48)

Rn = 330 W⋅m−2, approximate value is provided by Kato et al. (4)

Daytime soil heat flux: G = 30 W⋅m−2, approximate value is provided by Kato et al. (4)

Bowen ratio: β = 0.7, approximate value is provided by Gu et al. (49)

Impacts of Large-Scale Flows and Stratospheric Ozone Depletion

The monsoon and westerly flows show an apparent spatial pattern with latitude and longitude (1, 50); thus, their impact on the local temperature could be briefly accounted for by using longitude and latitude in the regressions. We use the partial correlation analysis between Tmax,trend and NDVItrend across the weather stations, setting the Tmin,trend and latitude and longitude as the controlling variables. We find that after adding the extra controlling variables of the latitude and longitude, Tmax,trend is still negatively and significantly (P < 0.05) related to NDVItrend (Fig. S12). In addition, there is no evidence suggesting that large-scale flows directly affect the spatial pattern of the interannual temperature trend over the plateau (31).

A recent study also suggests that the greater stratospheric ozone depletion over higher latitudes of the plateau may have contributed to more significant warming in the northern part of the plateau during the past few decades (32). If this effect is dominant, there should be a consistently greater Tmax trend for the higher latitudes of the plateau. Our results show a greater increase in Tmax with higher latitude from 1982 to 1999 in the northern areas, as supported by a positive correlation between Tmax,trend and latitude (R = 0.78, P < 0.01), but this latitudinal pattern is reversed for the period 2000–2010, with Tmax,trend being negatively correlated with latitude (R = −0.51, P < 0.01). Hence, there is no clear correlative evidence for mechanisms linking stratospheric ozone depletion, and surface temperature. Also, these mechanisms involve complex stratospheric chemistry, stratospheric circulation, and radiative balance processes, and are coupled with the tropospheric circulation, all of which are beyond the scope of this paper.

Discussion

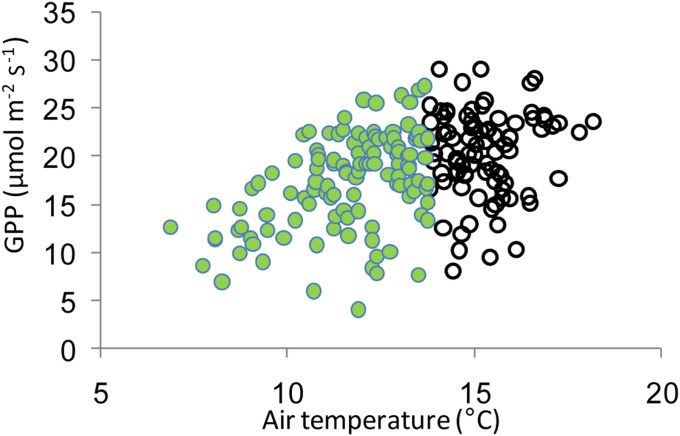

The TP has a cold climate and is covered by cold grasslands that are similar to the cold grasslands of dry-tundra regions of the Arctic. However, in contrast to the Arctic, where increasing vegetation activity is estimated to warm local climate by reducing albedo (14, 15), the climate feedback of increased vegetation activity appears to be negative in the TP, due to the dominance of ET-induced cooling over albedo-induced warming in case of an increase of vegetation greenness. We believe that the predominant role of ET cooling is caused by the much higher level of solar radiation (29) found at the relatively low latitude of the TP compared with the level of solar radiation in the high-latitude Arctic. The temperature is low on the TP, and the temperature when TP vegetation photosynthesis reaches its maximum is also correspondingly low (33) (Fig. S13); cool growing season temperatures over the TP are thus probably not a strong limitation on ET. Under the high radiation, increased vegetation needs to transpire more water, thus sustaining cooling feedbacks during the growing season. Hence, the findings from high latitudes cannot be simply transferred to the TP.

Fig. S13.

Relationships between gross primary production and air temperature (°C) in an alpine wetland at 4,285 m above sea level (asl) in the plateau (53). The half-hour GPP in early August reaches maximum at about 13.8 °C, as determined using piecewise regression according to Wang et al. (54). The GPP was derived according to the method of Reichstein et al. (55) from CO2 flux measurement by the eddy-covariance technique during August 3–14, 2011. On a weekly scale, the GPP also reaches a maximum at a temperature lower than 12 °C in an alpine shrubland (3,293 m asl), alpine marsh (3,160 m asl), and alpine meadow-steppe (4,333 m asl) on the plateau (33).

Accurate simulation of land-surface processes in the TP, such as ET and sensible heat flux into the atmosphere, is essential for characterizing the land/climate coupling that strongly affects the Asian monsoon (9). It has been projected that vegetation productivity across the TP will continue to be enhanced under future climate warming (5, 34). Unlike the Arctic ecosystem, evaporative cooling with water supplied by melting soil-ice may continue over this region.

We are aware that a statistical correlation, no matter how strong, does not imply causality. Also, data uncertainties and model deficiencies prevent us from reaching a quantitative conclusion on the magnitude of the evaporative cooling feedback induced by increased vegetation activity over the TP. The differences in observed ET and residual atmospheric effects on the NDVI would result in the difference in the magnitude of ET sensitivity to the NDVI. For instance, the machine-learning algorithm (ETJ) used static climatic variables (25); the Priestley and Taylor equation-based ETG (24) used satellite-observed precipitation that is reported biased over the TP (Fig. S6), which may lead to an unrealistic ET response to change in the NDVI; and the ETM used biophysical parameters for certain biomes globally (23) that may not accurately account for the unique TP vegetation and environment. Empirical analyses of observational data cannot quantitatively separate the compound impacts of multiple factors on Tmax, nor can they accurately determine the sensitivity of Tmax to greening. Nevertheless, the significant correlations between Tmax,trend and NDVItrend and between Tmax,trend and ETtrend, as well as the enhancing effect of greening on ET, did suggest that greening could have a cooling effect.

Further attribution needs both observational and modeling studies on all relevant physical mechanisms, which is challenging due to the scarcity of adequate observations and credible models over the TP. Consequently, the magnitude of the vegetation/climate feedbacks estimated here is still largely uncertain, as demonstrated by the difference between observations and the WRF model estimates. These differences highlight the need for further constraining land surface biogeophysical, hydrological, and other processes in climate models. Unfortunately, in the TP, the in situ data needed to characterize these processes are scarce and incomplete. Collecting new data should be a high priority: Measurements of all radiation components, sensible and latent heat fluxes, and ground heat storage are needed across a representative transect over the TP. Such data will allow us to quantify the feedbacks between the vegetation conditions and the surface heat fluxes. They will also help modelers to have a more realistic parameterization of surface processes in climate models. Experiments with these improved models should then result in better understanding of the role of the TP in the global climate system.

Methods

NDVI Data.

We used NDVI data derived from observations by three space-borne sensors: the AVHRR onboard National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration satellites (7, 9, 11, 14, 16–18), the MODIS onboard the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Earth Observing System’s satellite Terra, and VEGETATION onboard the satellite SPOT. The AVHRR NDVI data covering the period 1982–2010 were produced at spatial and temporal resolutions of 8 km and 15 d by the Global Inventory Modeling and Mapping Studies group (35). The MODIS NDVI data for the period 2000–2010 are from Collection 5, MOD13A2, with a 16-d composite and 1-km spatial resolution. Unlike the AVHRR, the MODIS has onboard calibration and precise orbit control, higher radiometric precision, atmospheric and viewing geometry corrections with physics-based algorithms, and higher fidelity (36). The SPOT NDVI dataset for the period 2000–2010 was produced every 10 d at a spatial resolution of 1 km. Compared with the biweekly AVHRR and MODIS NDVIs, the temporal resolution of the SPOT NDVI is 10 d, which gives 36 composites for a 1-y cycle (37). Averages of monthly NDVI data during the growing season were used to infer vegetation growth.

Climate Data.

Daily Tmax, Tmin, and Tmean, as well as daily precipitation, for the period 1982–2010 were recorded at 55 meteorological stations with no missing data. These data were provided by China Meteorological Data Sharing System (cdc.nmic.cn/home.do).

ET Data.

ET was extracted from three ET datasets produced by using the MODIS satellite observations (ETM), the Priestley and Taylor equation driven by satellite data (ETG), and a machine-learning algorithm using flux-tower ET measurements (ETJ). The theoretical model based on the Penman–Monteith equation (38) is driven by MODIS data and daily meteorological data to produce global ET (ETM) (23). The Priestley and Taylor equation is driven by a variety of satellite-sensor products to estimate daily transpiration globally at 0.25° × 0.25° (ETG) (24). The machine-learning algorithm is first trained mainly by ET measurements at the observing flux-tower sites of FluxNet and is then driven by surface geophysical information from satellite remote sensing and meteorological data to produce global monthly ET at 0.5° × 0.5° (ETJ) (25).

WRF Model.

We also used WRF3.2 (26) to investigate the feedback of vegetation growth change on daytime temperature during the growing season. The model domain covers the TP, having 90 × 60 grid points in each of the zonal and meridional directions, with a horizontal grid spacing of 50 km. There are 27 vertical layers between the model top at 70 hPa and the surface, and the time step of the model integration is 180 s. The R-2 reanalysis data (39) from the National Center for Environmental Prediction/DOE are used to obtain the initial and lateral boundary data. The monthly satellite-retrieved LAI (40) from the AVHRR NDVI was linearly interpolated to give daily values and used to prescribe the model’s lower boundary every 24 h. The model physics include the Kain–Fritsch convective parameterization scheme (41, 42), the WRF single moment 3-class cloud microphysics scheme (43), the National Center for Atmospheric Research Community Atmosphere Model (CAM3) radiation scheme (44), the YonSei University planetary boundary layer scheme (45), and the Noah land surface model (27). The Noah model was initialized using the vegetation categories from the USGS 24-category, 30-s dataset and soil texture derived from the US Department of Agriculture’s 16-category State Soil Geographic Database. The initial soil moisture state and lower soil boundary temperatures come from the reanalysis data. We used four soil layers in the Noah land surface model; the thicknesses of the layers from top to bottom are 0.1, 0.3, 0.6, and 1.0 m, with a total soil depth of 2 m.

Analyses.

To quantify the feedback of vegetation growth change on temperature during the growing season (May–September), we performed a multiple linear regression analysis in which Tmax,trend (or Tmin,trend) for each climate station was set as the dependent variable and NDVItrend and Tmin,trend (or Tmax,trend) were set as independent variables. This procedure removes the confounding effect of the temperature correlation between daytime and nighttime, and defines the coefficient of NDVItrend as the net effect. The corresponding NDVI value for each meteorological station was derived by averaging the NDVI over a window of 3 × 3 AVHRR NDVI pixels (or equivalent areas of MODIS and SPOT NDVIs) with the data from the meteorological station in the central pixel.

We performed two simulations using the WRF model with the Noah land surface scheme: one without (S1) and one with (S2) forced day-to-day changes in the LAI derived from the AVHRR NDVI during the period 1982–2010 (40). The integration period was 5 mo (May to September), starting each May 1 for 29 y. In the S1 simulation, throughout the entire period 1982–2010, the vegetation was prescribed with the LAI of 1982, whereas in the S2 simulation, vegetation growth varied with the satellite-derived LAI data from 1982 to 2010. The net effect of interactions between vegetation growth and temperature on Tmax was derived from a multiple linear spatial regression analysis in which the growing season Tmax difference between the S2 and S1 simulations (ΔTmax) for each grid over the plateau was set as the dependent variable and ΔTmin and ΔNDVI were set as independent variables. The effect of ET on Tmax (Tmin) was investigated by using spatial partial correlation between ΔET and ΔTmax (ΔTmin) and setting ΔTmin (ΔTmax) as the controlling variable. The sensitivity of Tmax (Tmin) to the NDVI was determined using spatial regression in which ΔTmax (ΔTmin) was set as the dependent variable and ΔNDVI and ΔTmin (ΔTmax) were set as the independent variables. The effect of vegetation on ET was determined using the spatial regression between ΔNDVI and ΔET.

We also used a sensitivity analysis based on intrinsic biophysical mechanisms (18) to estimate how much Ts would change for an NDVI increase of 0.1. It is assumed that two adjacent blocks of grassland share the same background climate state and have no horizontal flow between them. The only difference is that one block has an NDVI value 0.1 greater than the other. The equations of the intrinsic biophysical mechanisms are then used to calculate the response of Ts to a difference in the NDVI, based on the observed ET and albedo response to the NDVI (Sensitivity Analysis Based on Intrinsic Biophysical Mechanisms).

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant XDB03030404), a National Basic Research Program of China (Grant 2013CB956303), a program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 41125004), and a grant from Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant 2015055).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.A. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1504418112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yao T, et al. Different glacier status with atmospheric circulations in Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Nat Clim Change. 2012;2(9):663–667. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen J, Ruedy R, Sato M, Lo K. Global surface temperature change. Rev Geophys. 2010 doi: 10.1029/2010RG000345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piao S, et al. Impacts of climate and CO2 changes on the vegetation growth and carbon balance of Qinghai-Tibetan grasslands over the past five decades. Glob Planet Change. 2012;98–99:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato T, et al. Temperature and biomass influences on interannual changes in CO2 exchange in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Glob Change Biol. 2006;12(7):1285–1298. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan K, et al. Application of the ORCHIDEE global vegetation model to evaluate biomass and soil carbon stocks of Qinghai-Tibetan grasslands. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2010;24(1):GB1013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, et al. Effects of warming and grazing on soil N availability, species composition, and ANPP in an alpine meadow. Ecology. 2012;93(11):2365–2376. doi: 10.1890/11-1408.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, et al. The impacts of climate change and human activities on biogeochemical cycles on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Glob Change Biol. 2013;19(10):2940–2955. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu XD, Yin ZY, Shao XM, Qin NS. Temporal trends and variability of daily maximum and minimum, extreme temperature events, and growing season length over the eastern and central Tibetan Plateau during 1961-2003. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2006 doi: 10.1029/2005jd006915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu GX, et al. Thermal controls on the Asian summer monsoon. Sci Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1038/srep00404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collatz GJ, et al. A mechanism for the influence of vegetation on the response of the diurnal temperature range to changing climate. Geophys Res Lett. 2000;27(20):3381–3384. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapin FS, Eugster W, McFadden JP, Lynch AH, Walker DA. Summer differences among Arctic ecosystems in regional climate forcing. J Clim. 2002;13(12):2002–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field CB, Lobell DB, Peters HA, Chiariello NR. Feedbacks of terrestrial ecosystems to climate change. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2007;32:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou L, Dickinson RE, Tian Y, Vose RS, Dai Y. Impact of vegetation removal and soil aridation on diurnal temperature range in a semiarid region: Application to the Sahel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(46):17937–17942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700290104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson RG, et al. Shifts in Arctic vegetation and associated feedbacks under climate change. Nat Clim Change. 2013;3(7):673–677. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapin FS, 3rd, et al. Role of land-surface changes in arctic summer warming. Science. 2005;310(5748):657–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1117368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bounoua L, et al. Sensitivity of climate to changes in NDVI. J Clim. 2000;13(13):2277–2292. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong SJ, Ho CH, Kim KY, Jeong JH. Reduction of spring warming over East Asia associated with vegetation feedback. Geophys Res Lett. 2009;36:L18705. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee X, et al. Observed increase in local cooling effect of deforestation at higher latitudes. Nature. 2011;479(7373):384–387. doi: 10.1038/nature10588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loarie SR, Lobell DB, Asner GP, Mu QZ, Field CB. Direct impacts on local climate of sugar-cane expansion in Brazil. Nat Clim Change. 2011;1(2):105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houspanossian J, Nosetto M, Jobbágy EG. Radiation budget changes with dry forest clearing in temperate Argentina. Glob Change Biol. 2013;19(4):1211–1222. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen B, et al. The impact of climate change and anthropogenic activities on alpine grassland over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Agric For Meteorol. 2014;189–190:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen M, et al. Increasing altitudinal gradient of spring vegetation phenology during the last decade on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agric For Meteorol. 2014;189–190:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mu Q, Zhao M, Running SW. Improvements to a MODIS global terrestrial evapotranspiration algorithm. Remote Sens Environ. 2011;115(8):1781–1800. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miralles DG, et al. Global land-surface evaporation estimated from satellite-based observations. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 2011;15(2):453–469. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung M, et al. Recent decline in the global land evapotranspiration trend due to limited moisture supply. Nature. 2010;467(7318):951–954. doi: 10.1038/nature09396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skamarock WC, et al. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF. Version 3 National Center for Atmospheric Research; Boulder, CO: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen F, Dudhia J. Coupling an advanced land surface-hydrology model with the Penn State-NCAR MM5 modeling system. Part I: Model implementation and sensitivity. Monthly Weather Review. 2001;129(4):569–585. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strahler AH, et al. MODIS BRDF/Albedo Product: Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document. Version 5.0 NASA; Greenbelt, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng D, Zhang Q, Wu WS. Mountain Geoecology and Sustainable Development of the Tibetan Plateau. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang K, Chen YY, Qin J. Some practical notes on the land surface modeling in the Tibetan Plateau. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 2009;13(5):687–701. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang K, et al. Recent climate changes over the Tibetan Plateau and their impacts on energy and water cycle: A review. Glob Planet Change. 2014;112:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo DL, Wang HJ. The significant climate warming in the northern Tibetan Plateau and its possible causes. Int J Climatol. 2012;32(12):1775–1781. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao Y, et al. A MODIS-based photosynthetic capacity model to estimate gross primary production in Northern China and the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens Environ. 2014;148:108–118. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su F, Duan X, Chen D, Hao Z, Cuo L. Evaluation of the global climate models in the CMIP5 over the Tibetan Plateau. J Clim. 2013;26(10):3187–3208. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tucker CJ, et al. An extended AVHRR 8-km NDVI dataset compatible with MODIS and SPOT vegetation NDVI data. Int J Remote Sens. 2005;26(20):4485–4498. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huete A, et al. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens Environ. 2002;83(1-2):195–213. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maisongrande P, Duchemin B, Dedieu G. VEGETATION/SPOT: An operational mission for the Earth monitoring; presentation of new standard products. Int J Remote Sens. 2004;25(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monteith JL. The State and Movement of Water in Living Organisms. Nineteenth Symposium of the Society of Experimental Biology. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1965. Evaporation and environment; pp. 205–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanamitsu M, et al. NCEP-DOE AMIP-II reanalysis (R-2) Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 2002;83(11):1631–1643. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu Z, et al. Global data sets of vegetation leaf area index (LAI)3g and fraction of photosynthetically active radiation (FPAR)3g derived from global inventory modeling and mapping studies (GIMMS) Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI3g) for the period 1981 to 2011. Remote Sens. 2013;5(2):927–948. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kain JS. The Kain-Fritsch convective parameterization: An update. Journal of Applied Meteorology. 2004;43(1):170–181. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kain JS, Fritsch JM. A one-dimensional entraining detraining plume model and its application in convective parameterization. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 1990;47(23):2784–2802. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong SY, Dudhia J, Chen SH. A revised approach to ice microphysical processes for the bulk parameterization of clouds and precipitation. Monthly Weather Review. 2004;132(1):103–120. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins WD, et al. Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 3.0) National Center for Atmospheric Research; Boulder, CO: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong S-Y, Noh Y, Dudhia J. A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. Monthly Weather Review. 2006;134(9):2318–2341. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang K, Koike T, Yang DW. Surface flux parameterization in the Tibetan Plateau. Boundary Layer Meteorol. 2003;106(2):245–262. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang K, et al. Turbulent flux transfer over bare-soil surfaces: Characteristics and parameterization. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. 2008;47(1):276–290. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang W, Yang K, He J, Qin J. Quality control and estimation of global solar radiation in China. Solar Energy. 2010;84(3):466–475. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu S, et al. Characterizing evapotranspiration over a meadow ecosystem on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2008 doi: 10.1029/2007JD009173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maussion F, et al. Precipitation seasonality and variability over the Tibetan Plateau as resolved by the high Asia reanalysis. J Clim. 2014;27(5):1910–1927. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin Z-Y, Zhang X, Liu X, Colella M, Chen X. An assessment of the biases of satellite rainfall estimates over the Tibetan Plateau and correction methods based on topographic analysis. Journal of Hydrometeorology. 2008;9(3):301–326. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yong B, et al. Global view of real-time TRMM Multi-satellite precipitation analysis: Implication to its successor Global Precipitation Measurement mission. Bull Amer Meteor Soc. 2015;96(2):283–296. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao R, Shen M, Chen J, Tang Y. A simple method to simulate diurnal courses of PAR absorbed by grassy canopy. Ecol Indic. 2014;46:129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, et al. Spring temperature change and its implication in the change of vegetation growth in North America from 1982 to 2006. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(4):1240–1245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014425108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reichstein M, et al. On the separation of net ecosystem exchange into assimilation and ecosystem respiration: Review and improved algorithm. Glob Change Biol. 2005;11(9):1424–1439. [Google Scholar]