Abstract

Objective:

To optimization of extraction of antioxidant compounds from guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves and showed that the guava leaves are the potential source of antioxidant compounds.

Materials and Methods:

The bioactive polysaccharide compounds of guava leaves (P. guajava L.) were obtained using ultrasonic-assisted extraction. Extraction was carried out according to Box-Behnken central composite design, and independent variables were temperature (20–60°C), time (20–40 min) and power (200–350 W). The extraction process was optimized by using response surface methodology for the highest crude extraction yield of bioactive polysaccharide compounds.

Results:

The optimal conditions were identified as 55°C, 30 min, and 240 W. 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl and hydroxyl free radical scavenging were conducted.

Conclusion:

The results of quantification showed that the guava leaves are the potential source of antioxidant compounds.

Keywords: Antioxidant, guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves, polysaccharide, ultrasonic-assisted extraction

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological studies indicate that frequent consumption of fruits is associated with lower risk of stroke and cancer.[1] The defensive effects of natural antioxidants in fruits and vegetables are related to three major groups: Vitamins, phenolics, and carotenoids. Ascorbic acid and phenolics are known as hydrophilic antioxidants while carotenoids are known as lipophilic antioxidants.[2]

Guava (Psidium guajava L.) is an important tropical fruit, mostly consumed fresh. The fruit is a berry, which consists of a fleshy pericarp and seed cavity with fleshy pulp and numerous small seeds. The leaves have been extensively used for the treatment of diarrhea,[3] bacterial infection, pain, and inflammation.[4] According to Hui-Yin and Gow-Chin,[5] the extracts from guava (P. guajava L.) leaves exhibited good antioxidant activity as well as free radical-scavenging capacity.[6] As far as we know, there are no comprehensive data reported on the variation of antioxidants during development of guava leaves.

In the most recent 30 years, numerous polysaccharides have been isolated from mushrooms, fungi, and plants and have been used as a source of therapeutic agents. The most promising bio-pharmacological activity of these biopolymers is their immunomodulation[7] and antioxidant effects. More recent surveys show polysaccharide is believed to play a significant role in the prevention of chronic and degenerative diseases.[8]

Conventional extractions such as heating, boiling, or reflux can be used to extract compounds in plants. However, disadvantages include the loss of some compounds due to oxidation, ionization, and hydrolysis during extraction as well as the long extraction times.[9] Recently, new extraction techniques have been developed for the extraction of target compounds from different materials including ultrasound and microwave-assisted, supercritical fluid and accelerated solvent extraction.[10] Among these, UAE is an inexpensive, simple, and efficient alternative to conventional extraction techniques.[11] The mechanism of action for UAE attributed to cavitation, mechanical forces, and thermal impact, which result in disruption of cells walls, reduce particle size, and enhance mass transfer across cell membranes.[12]

Response surface methodology (RSM) is a kind of optimization method which serves as an accurate, effective, and simple tool for optimizing the experimental process,[13,14] and is widely used in agriculture, biology, food, chemistry, and other fields.[15,16,17] Therefore, using RSM in UAE could be an excellent method to optimize the extraction. There are no reports on optimization of extraction of polysaccharides from guava leaves by UAE, hence, there is a need to develop a suitable extraction method with optimum polysaccharides which can be applied on an antioxidant compounds. A Box–Behnken central composite design (CCD)[18] was employed to study the influence of temperature, time, and ultrasonic power on the extraction yield of polysaccharides from guava leaves and to optimize the extraction condition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material and reagents

Fresh guava leaves were collected from farms in Shilou town of Guangzhou, Guangdong. This specie was locally called as pearl guava leaves. Samples were transferred on the same day to Pharmaceutical Engineering Lab in Guangdong Pharmaceutical University and were dried in 60°C then stored until analysis. 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. salicylic acid, sodium tungstate, sodium nitrite, EtOH, FeSO4, etc., All chemicals used were of analytical grade and were purchased from a local Chemical Co. (Congyuan Co., Ltd, Guangzhou).

Ultrasound-assisted extraction

Ultrasound-assisted extraction was performed in a temperature controlled by ultrasonic cleaner (KH-400KDB, Hechuang Ultrasonic Equipment Co., KunShan, China). Furthermore, temperature was also monitored with a thermometer. The guava leaves powder (2.0 g) was put in a glass vial (100 mL) and distilled water solvent (50 mL) added before the vial was placed in the ultrasonic cleaning bath (united) at 40 kHz. The extract was combined, filtered, and concentrated in a rotary evaporator to small volumes. Subsequently, four volumes of ethanol were added to the supernatant, the mixture was maintained for 24 h at room temperature to precipitate polysaccharide, and the precipitate was collected by centrifugation. Polysaccharide content was determined with a phenol–sulfuric acid method[19] using glucose as a standard. The crude extraction yield of polysaccharide of antioxidant compounds was then measured gravimetrically and reported as follows Eq. 1:

Where Y is the crude extraction yield (%), w0 is the crude extract mass (g), and ws is the extracted sample mass (g).

Experimental design

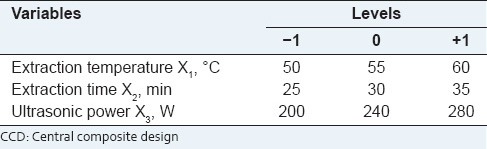

Response surface methodology was used to determine the influence of three independent variables, extraction temperature (X1) extraction time (X2) and ultrasonic power (X3), considered the most important variables affecting guava leaves extraction. The experimental design was a modification of Box's CCD, for three factors each at three levels [Table 1]. The lower (−1), middle (0), and upper levels (+1) of three independent variables were then determined using RSM.[20]

Table 1.

The levels of variables employed in the present study for the construction of Box-Behnken design (CCD)

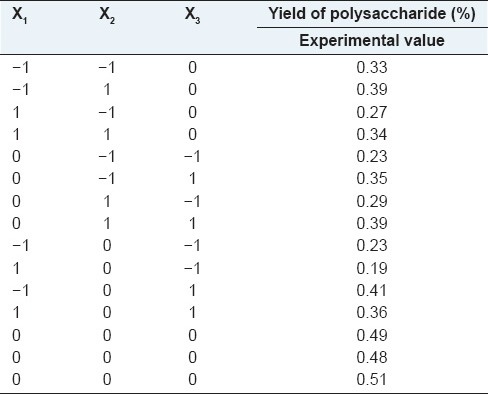

The end and central values were chosen from the results of preliminary tests. The experimental design consisted of 15 points, including three replications at the central point [Table 2] and was carried out in a random order.

Table 2.

Experimental design and result of factors chosen for the trials of Box-Behnken

Response surface graphs were plotted, and optimum responses were identified within feasible treatments for the different response-dependent variables. The response surface regression (RSREG) procedure uses the method of least squares to fit quadratic RSREG models. Response surface model analysis by the RSREG procedure was performed according to the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

For statistical calculations, the relation between the coded values and real values is described as follows Eq. 2:

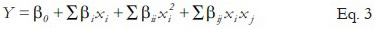

xi, x0, and Δx indicated dimensionless coded value of the variable Xi, the real value of the Xi at the center point, and the step change of variable, respectively. The following quadratic equation explains the behavior of the system as Eq. 3:

Y, β0, βi, βii and βij indicated the predicted response, the intercept term, the linear coefficient, the squared coefficient, and the interaction coefficient, respectively.

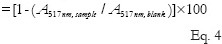

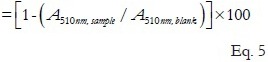

1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl free radical scavenging effect

The removal of DPPH radical effect for each sample was determined by a modified method of Hsiang et al. and Yamaguchi et al.[21,22] Briefly, 0.1 mL of 10 mM DPPH solution (in methanol) was added to a test tube containing 4 mL of the guava leaves extracts (120, 240, 360 mg) as low, middle, high levels. The mixture was shaken vigorously for 15 s and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Methanol was used as a blank control. Butylated hydroxytoluene was used as positive controls. The absorbance of each sample solution was measured at 517 nm by a spectrophotometer (U-752, Shunyuheng Co., Ltd, China). The experiment was performed triplicate. The percentage of free radical scavenging effect was calculated as Eq. 4:

DPPH scavenging effect(%)

Where A517nm, sample and A517nm, blank were the absorbance values at 517 nm for sample and blank, respectively.

Hydroxyl free radical scavenging effect

Among all known reactive oxygen species, hydroxyl radical (-OH) is the most damaging one, which may be produced under the physiological conditions and reacts rapidly with almost any biological molecule and may be involved in pathology of many human diseases.[23]

We used methods for an -OH production system for analyzing -OH scavenging activity: The Fenton reaction system. The typical procedure for using a Fenton system is as follows: -OH attack aromatic compounds to produce hydroxyl compound, so the -OH in Fenton reaction system can be captured by salicylic acid, and the generated 3-dihydroxybenzoic acid can be extract by EtOH and colored by sodium tungstate and sodium nitrite. Then measured with a spectrophotometer at 510 nm, this absorbance value can reflect the concentration of -OHs in the system. 2 mL FeSO4(6 mmol/mL), 2 mL H2O2(6 mmol/mL), and 2 mL salicylic acid-EtOH (6 mmol/mL) were mixed with 2 mL sample solution of 30, 60, 90 (mg/mL). Blank contain 2 mL H2O instead of sample. Then the mixture was put in 37°C water-bath for 30 min. After that, the absorbance was determined at 510 nm. The -OH scavenging rate of sample solution was calculated by the following Eq. 5:

-OH scavenging effect(%)

Where A510nm, sample and A510nm, blank were the absorbance values at 510 nm for sample and blank, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of independent variables on the polysaccharide yield

A range of temperature treatments (20–60°C) were employed for 30 min with ultrasonic power at 240 W to assess their effect on the extraction polysaccharide from guava leaves. The results show the yield of polysaccharide increased as temperature increased from 20°C to 40°C; however, when the temperature exceeded 40°C, the yield of polysaccharide exhibited a linear decrease. As the temperature increased, the solvent viscosity and density decreased resulting in an increase of mass transfer.[24,25,26] In addition, the number of cavitation bubbles within the fluid increased creating a cohesive force reducing the tensile strength of the liquid as a result of decreased solvent viscosity.[27,28] Therefore, 40°C was chosen for subsequent treatment optimization.

The effect of extraction time on the polysaccharide yield

The tests compared extractions in distilled water with ultrasonic power at 240 W with extraction temperature 60°C for different treatment times: 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 min. The results showed how the polysaccharide yield increased significantly in the initial 20 min, then slowed until reaching an equilibrium. All guava leaves cell walls cracked completely within the first 30 min from the acoustic cavitation effect, leading to good penetration of the solvent into the cells, and enhancing the transfer of dissolved polysaccharide out of the solid structure.[29] As the guava leaves cell walls ruptured, impurities such as insoluble substances, cytosol, and lipids suspend in the extract, lowering the solvent's permeability into cell structures.[30,31] Furthermore, some polysaccharide will be decomposed with too long extraction time. Therefore, a longer extraction time is unnecessary once the maximum extraction yield is achieved. Based on these results, 30 min was selected as the optimum for this treatment.

The effect of electrical power on the polysaccharide yield

The effect of five electrical power levels on the guava leaves polysaccharide yield was studied to evaluate the effect of ultrasonic power on polysaccharide yield: 200, 240, 280, 320, and 360 W at 60°C for 30 min. Ultrasonic power had a significant effect on the extraction of polysaccharide. When the power was increased from 200 to 280 W, the yield of polysaccharide increased significantly and almost linearly. Sonication is widely used for extraction of various substances from plant material and generates microscopic bubbles. The type and number of bubbles created and collapsed are positively correlated to the amplitude of ultrasonic waves traveling through the solvent; the collapsing bubbles are believed to create high-shear gradients by causing micro streaming which disrupts the cell walls. This significantly accelerates the penetration of solvent into cells, and the release of components from cells into the solvent, and simultaneously significantly enhances the mass transfer rate. As a result, the yield of polysaccharide increased proportionately with the increase in ultrasonic power. SivaKumar et al.[32] and Lou et al.[33] had similar results using UAE of tannin from my robalan nuts and polysaccharide from chick peas. However, increasing the ultrasonic power exceeding 280 W resulted in a slight decrease in the polysaccharide yield from guava leaves; 280 W was chosen to optimize the treatment.[34]

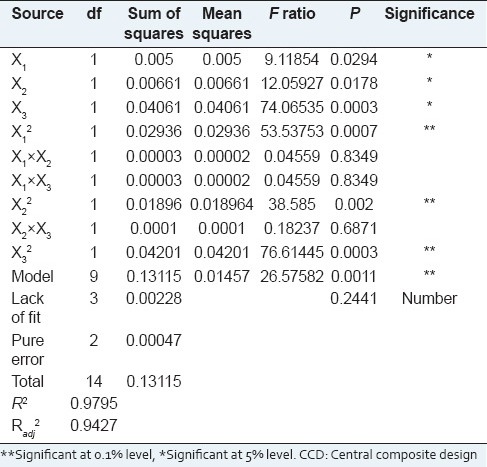

Response surface analysis

The results of different runs are shown in Table 2. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine the significant effects of process variables on the response. The estimated regression coefficients of three independent variables, along with the corresponding R2, Radj2, P values, and lack of fittest for the reduced response surface model, are displayed in Table 3. A high R2(0.9795) indicates that the data fitted satisfactorily to the second-order polynomial reduced model. Thus, more than 99% of the response variation could be accurately explained.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients of the final regression model and AVOVA for the extraction yield of polysaccharide in the CCD design

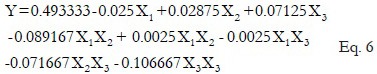

Model fitting

The mathematical model representing the extraction yield of guava leaves as a function of the independent variables was expressed by the following Eq. 6:

Where Y is the extraction yield of guava leaves and X1, X2, and X3 are the uncoded variables for extraction temperature, extraction time, and ultrasonic power respectively.

In general, exploration and optimization of a fitted response surface may produce poor or misleading results unless the model exhibits a good fit, which makes checking the model adequacy essential.[35,36,37] The P value of the model was less than 0.05 (P < 0.05), which indicated that the model fitness was significant [Table 3]. Meanwhile, the lack of fit value of the model was nonsignificant (0.2441), indicating that the model equation was adequate for predicting the crude extraction yield under any combination of values of the variables [Table 3]. Coefficient (R2) of the determination is defined as the ratio of the explained variation to the total variation and is a measurement of the degree of fitness.[38] A small value of R2 indicates a poor relevance of the dependent variables in the model.[39] By ANOVA, the R2 value of this model was determined to be 0.9795, which showed that the regression model defined well the true behavior of the system.

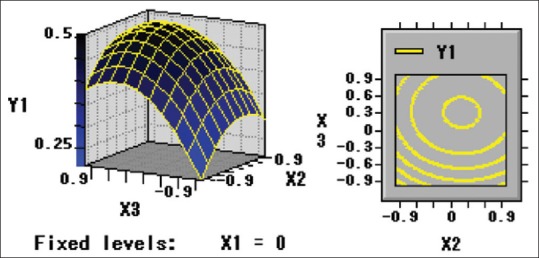

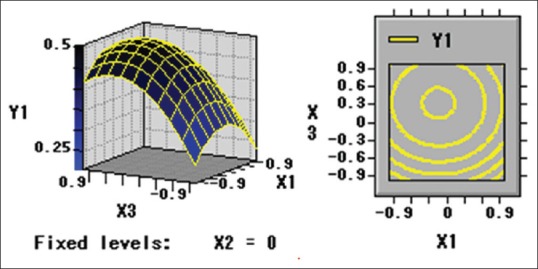

Numerical optimization was carried out using response optimizer to predict the optimal condition in order to obtain the highest crude extraction yield of guava leaves. Based on this information (Eq. 1) using RSM, the three-dimensional response surface plots and two-dimensional contours were generated to determine the levels of the processing variables to achieve the optimal yield of polysaccharide of guava leaves [Figures 1-3].

Figure 1.

Y1 = f (X1, X2)

Figure 3.

Y1 = f (X2, X3)

Figure 2.

Y1 = f (X1, X3)

By Eq. 1 and Eq. 2, the optimal values of the three variables were calculated to be 53.58°C, 30.93 min and 253.25 W for extraction temperature, extraction time, and ultrasonic power, respectively. The maximum predicted yield of polysaccharide of guava leaves was 0.51% under optimal conditions. For operational convenience, the optimal parameters are 55°C, 30 min, and 240 W for extraction temperature, extraction time, and ultrasonic power, respectively. Five verification experiments were carried out under the optimum conditions to validate the adequacy of the model equation. A mean polysaccharide extraction value of 0.49% ± 0.03% was obtained from laboratory experiments. The regression model proved adequate in predicting the optimal conditions achievable in laboratory settings.

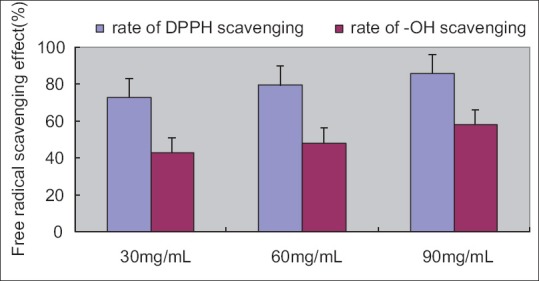

Antioxidant effect of guava leaves

In this study, it was demonstrated that the extracts of guava leaves were at concentration of 30–90 mg/mL, DPPH scavenging capacity was 72–86% and the -OH scavenging activity was 42.94–58.33%. The DPPH and the -OH free radical scavenging capacity of polysaccharide of guava leaves increased in a concentration-dependent manner [Figure 4]. The DPPH is decolorized by accepting an electron donated by an antioxidant. The reducing potential of a substrate usually depends on the concentration of reductants, which exhibit antioxidant activity by donating a hydrogen atom and breaking the chain of free radicals. The increases in concentration of antioxidants are linked to increasing the scavenging of DPPH and thus an indication of higher antioxidant activity. The present results also appear to show that polysaccharide of guava leaves is an ideal -OH scavengers, and it will be done more vivo studies in the future.

Figure 4.

Free radical scavenging effect (%)

CONCLUSION

The high correlation of the mathematical model indicated that a quadratic polynomial model could be employed to optimize extraction yield from guava leaves by UAE. From the response surface plots, three factors (temperature, time, and ultrasonic power) significantly influenced the crude extraction yield independently. The optimal conditions to obtain the highest crude extraction yield of guava leaves were determined to be 55°C, 30 min and 240 W. Under the optimal conditions, the difference between experimental value (0.49% ± 0.03%) and predicted value (0.51%) was small. Thus, this methodology could provide a basis for a model to examine the nonlinear nature between independent variables and response in a short-term experiment. Furthermore, by antioxidant assay, the guava leaves are a potential source of antioxidant compounds. Plant sources like guava leaves may bring new natural products into the food industry with safer and better antioxidants that provide good protection against oxidative damage, which occurs both in the body and in the processed food.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the Open Project Program of Provincial Key Laboratory of Green Processing Technology and Product Safety of Natural Products (No.201303).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beecher GR. Phytonutrients’ role in metabolism: Effects on resistance to degenerative processes. Nutr Rev. 1999;57:S3–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1999.tb01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halliwell B. Antioxidants in human health and disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 1996;16:33–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaljee L, Thiem VD, von Seidlein L, Genberg BL, Canh DG, Tho le H, et al. Healthcare use for diarrhoea and dysentery in actual and hypothetical cases, Nha Trang, Viet Nam. J Health Popul Nutr. 2004;22:139–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ojewole JA. Antiinflammatory and analgesic effects of Psidium guajava Linn. (Myrtaceae) leaf aqueous extract in rats and mice. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2006;28:441–6. doi: 10.1358/mf.2006.28.7.1003578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui-Yin C, Gow-Chin Y. Antioxidant activity and free radical-scavenging capacity of extracts from guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves. Food Chem. 2007;101:686–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gull J, Sultana B, Anwar F, Naseer R, Ashrafand M, Ashrafuzzaman M. Variation in antioxidant attributes at three ripening stages of guava (Psidium guajava L.) fruit from different geographical regions of Pakistan. Molecules. 2012;17:3165–80. doi: 10.3390/molecules17033165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ker YB, Peng CH, Chyau CC, Peng RY. Soluble polysaccharide composition and myo-inositol content help differentiate the antioxidative and hypolipidemic capacity of peeled apples. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:4660–5. doi: 10.1021/jf903495h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang ZS, Wang LJ, Li D, Jiao SS, Chen XD, Mao ZH. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of oil from flaxseed. Sep Purif Technol. 2008;62:192–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H, Chen B, Yao S. Application of ultrasonic technique for extracting chlorogenic acid from Eucommia ulmodies Oliv. (E. ulmodies) Ultrason Sonochem. 2005;12:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Weller CL. Recent advances in extraction of Nutraceuticals from plants. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2006;17:300–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Yang B, Du X, Yi C. Optimization of supercritical fluid extraction of flavonoids from Pueraria lobata. Food Chem. 2008;108:737–41. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan Z, Qu W, Ma H, Atungulu GG, McHugh TH. Continuous and pulsed ultrasound-assisted extractions of antioxidants from pomegranate peel. Ultrason Sonochem. 2011;18:1249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao S, Wang J, Shi D. Beijing, China: Science Press; 2003. Statistical Handbook; pp. 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilde W, Nigel B. The optimization of solid-liquid extraction of antioxidants from apple pomace by response surface methodology. J Food Eng. 2010;96:134–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Wang T, Ding L. Optimization of polysaccharide extraction from Angelica sinensis using response surface methodology. Food Sci. 2012;33:146–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song X, Gao Y, Yuan F. Optimization of antioxidant peptide production from goat placenta powder using RSM. Food Sci Technol. 2008;33:237–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C, Jia S, Xu J. Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis for protein from Actinidia arguta Sieb. et Zucc by response surface methodology and antioxidant activity of polypeptides. Food Sci. 2012;33:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Box GE, Van Behnken EE. Some new three level designs for the study of quantitative variables. Technometrics. 1960;2:455–75. [Google Scholar]

- 19.DuBois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric 405 method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cacace JE, Mazza G. Optimization of extraction of anthocyanins from black currants with aqueous ethanol. J Food Sci. 2003;68:240–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu HW, Peng JC, Tsai SJ, Lui WB. Effect of extrusion processing on antioxidant activities of corn extrudates fortified with various Chinese yams (Dioscorea sp.) Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012;5:2462–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi T, Takamura H, Matoba T, Terao J. HPLC method for evaluation of the free radical-scavenging activity of foods by using 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:1201–4. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng Z, Zhou H, Yin J, Yu L. Electron spin resonance estimation of hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity for lipophilic antioxidants. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:3325–33. doi: 10.1021/jf0634808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang M, Cui SW, Cheung P, Wang Q. Antitumor polysaccharides from mushrooms: A review on their isolation process, structural characteristics and antitumor activity. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2007;18:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbasi H, Rezaei K, Rashidi L. Extraction of essential oils from the seeds of pomegranate using organic solvents and supercritical CO2. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2008;85:83–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalmashi A. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of oil from tea seeds. J Food Lipids. 2009;16:465–74. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toma M, Vinatoru M, Paniwnyk L, Mason TJ. Investigation of the effects of ultrasound on vegetal tissues during solvent extraction. Ultrason Sonochem. 2001;8:137–42. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(00)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palma M, Barroso CG. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and determination of tartaric and malic acids from grapes and winemaking by-products. Anal Chim Acta. 2002;458:119–30. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paniwnyk L, Beaufoy E, Lorimer JP, Mason TJ. The extraction of rutin from flower buds of Sophora japonica. Ultrason Sonochem. 2001;8:299–301. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(00)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong J, Liu Y, Liang Z, Wang W. Investigation on ultrasound-assisted extraction of salvianolic acid B from Salvia miltiorrhiza root. Ultrason Sonochem. 2010;17:61–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu G, Xu X, Hao Q, Gao Y. Supercritical CO2 extraction optimization of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed oil using response surface methodology. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2009;42:1491–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sivakumar V, Verma R, Rao VV, Swaminathan PG. Studies on the use of power ultrasound in solid-liquid myrobalan extraction process. J Clean Prod. 2007;15:1813–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lou Z, Wang H, Zhang M, Wang Z. Improved extraction of oil from chickpea under ultrasound in a dynamic system. J Food Eng. 2010;98:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian Y, Xu Z, Zheng B, Martin Lo Y. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) seed oil. Ultrason Sonochem. 2013;20:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liyana-Pathirana C, Shahidi F. Optimization of extraction of phenolic compounds from wheat using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2005;93:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scavroni J, Boaro CS, Marques MO, Ferreira LC. Yield and composition of the essential oil of Mentha piperita L. (Lamiaceae) grown with biosolid. Braz J Plant Physiol. 2005;17:345–52. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bimakr M, Rahman RA, Ganjloo A, Taip FS, Salleh LM, Sarker MZ. Optimization of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of bioactive flavonoid compounds from spearmint (Mentha spicata L.) leaves by using response surface methodology. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012;5:912–20. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Sun B, Cao Y, Tian Y, Li X. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from wheat bran. Food Chem. 2008;106:804–10. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sin HN, Yusof S, Hamid NS, Rahman RA. Optimization of enzymatic clarification of sapodilla juice using response surface methodology. J Food Eng. 2006;73:313–9. [Google Scholar]