Abstract

Background:

Yanggyuksanhwa-tang (YGSHT) is a specific traditional Korean herbal formula for Soyangin according to Sasang constitutional philosophy. Although its biological activities against inflammation and cerebral infarction have been reporting, there is no information about the adipogenic activity of YGSHT. In the present study, we investigated the anti-adipogenic activity of YGSHT to evaluate effects of YGSHT on adipogenesis in vitro.

Materials and Methods:

Using 3T3-L1 preadipocytes, we induced the cellular differentiation into adipocytes by adding insulin. Anti-adipogenic activity of YGSHT was measured by oil red O staining, triglyceride assay, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) activity test, and leptin assay.

Results:

YGSHT extract had no significant cytotoxicity in preadipocytes or differentiated adipocytes. YGSHT reduced the number of lipid droplets and content of triglyceride in adipose cells. YGSHT also significantly inhibited GPDH activity and decreased leptin production compared with control adipocytes. Down-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) expression at the messenger RNA level was observed in YGSHT-treated adipocytes.

Conclusion:

Taken together, our data suggest that YGSHT has potential as an anti-obesity drug candidate.

Keywords: 3T3-L1, adipogenesis, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, Yanggyuksanhwa-tang

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a condition characterized by excess body fat accumulation and is defined as a body mass index, >30 kg/m2. Globally, the number of obese people is increasing rapidly and has almost doubled since 1980.[1] Obesity is a major risk factor for various diseases such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, cancer, and osteoarthritis.[2] In Western medicine, various anti-obesity medications have been developed, including orlistat, lorcaserin, and sibutramine. However, these medications have serious side effects such as steatorrhea, high blood pressure, constipation, insomnia, and hepatotoxicity, which can limit their long-term use. Thus, novel preventive and therapeutic options with greater efficacy and fewer side effects are needed.

Complementary and alternative medicine is an attractive therapy for obesity and obesity-related diseases because it has fewer side effects, and less toxicity compared with Western medicines.[3] For example, Han et al. reported that Wen-pi-tang-hab-wu-ling-san, a polyherbal medicine, attenuated endoplasmic reticulum stress in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes by promoting the insulin signaling pathway.[4] Ikarashi et al. reported that the herbal medicine Orengedokuto had inhibitory effects on adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cultures.[5] Kwak et al. reported that Hwangryunhaedok-tang negatively regulated 3T3-L1 adipogenesis via the Raf/MEK1/ERK1/2 pathway and PDK1/Akt phosphorylation.[6] These results suggest that the herbal prescriptions have potential as anti-obesity agents by targeting adipogenesis.

Sasang constitution is a Korean medicinal theory based on traditional Oriental philosophy and classifies people into four types according to the four internal organs: Lung, spleen, liver, and kidney. Soyangin is defined as a group of people with a large spleen and small kidney. Yanggyuksanhwa-tang (YGSHT) is a specific herbal formula for Soyangin in accordance with Sasang constitutional philosophy. YGSHT has been used to reduce fever in patients with diabetes, stroke, and acute contagious disease. However, there are few scientific papers on the pharmacological efficacy of YGSHT, except for its effects on inflammation[7] and cerebral infarction.[8]

Here, we report that YGSHT exerted an anti-adipogenesis effect in an in vitro obesity model. We evaluated fat accumulation using oil red O staining and by measuring triglyceride concentration, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) activity, and leptin production in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Neomagiferin (≥98.0%) and mangiferin (≥98.0%) were purchased from Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals (Chengdu, China). Chlorogenic acid (≥98.0%) and caffeic acid (≥98.0%) were purchased from Acros Organics (Pittsburgh, PA). Geniposide (≥98.0%), sweroside (≥94.0%), and pinoresinol (≥98.0%) were obtained from Wako (Osaka, Japan), and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), respectively. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade reagents, methanol, acetonitrile, and water were obtained from J.T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ). Formic acid was procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Plant materials

The nine herbal medicines forming YGSHT were purchased from Omniherb (Yeongcheon, Korea) and HMAX (Jecheon, Korea). The origin of these herbal medicines was taxonomically confirmed by Prof. Je Hyun Lee, Dongguk University, Gyeongju, Korea. A voucher specimen (2008–KE10-1-KE10-9) has been deposited at the Herbal Medicine Formulation Research Group, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine.

Preparations of standard and sample solutions

Standard stock solutions of seven compounds, neomangiferin, chlorogenic acid, mangiferin, geniposide, sweroside, caffeic acid, and pinoresinol were dissolved in methanol at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL and were stored below 4°C. Working standard solutions were prepared by serial dilution of stock solutions with methanol.

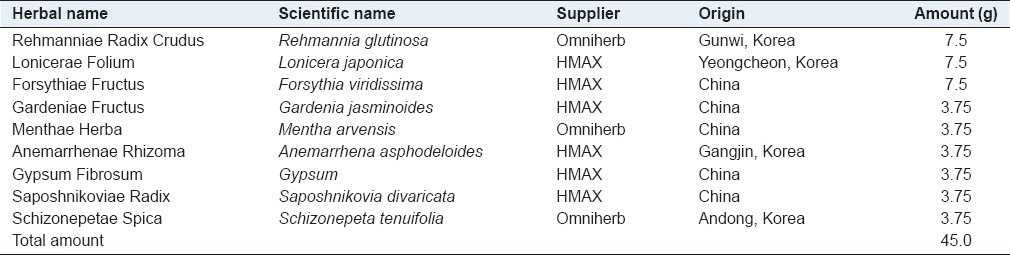

YGSHT comprising nine herbal medicines including Rehmannia glutinosa, Lonicera japonica, Forsythia viridissima, Gardenia jasminoides, Mentha arvensis, Anemarrhena asphodeloides, Gypsum, Saposhnikovia divaricata, and Schizonepeta tenuifolia was mixed [Table 1; 3.5 kg; 45.0 g × 77.8 g] and extracted in a 10-fold mass of water (35 L) at 100°C for 2 h under pressure (1 kgf/cm2) using an electric extractor (COSMOS-660; Kyungseo Machine Co., Incheon, Korea), and the water extract was then filtered through a standard sieve (no. 270, 53 μm; Chung Gye Sang Gong Sa, Seoul, Korea) and the solution was evaporated to dryness and freeze-dried to give a powder. The yield of YGSHT water extract was 16.2% (570.1 g). For HPLC analysis, 200 mg of lyophilized YGSHT water extract was dissolved in 20 mL of 70% methanol and then extracted by the sonicator for 10 min. The solution was filtered through a 0.2 μm syringe filter (Woongki Science, Seoul, Korea) before injection into the HPLC system.

Table 1.

Composition of Yanggyuksanhwa-tang

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of Yanggyuksanhwa-tang water extract

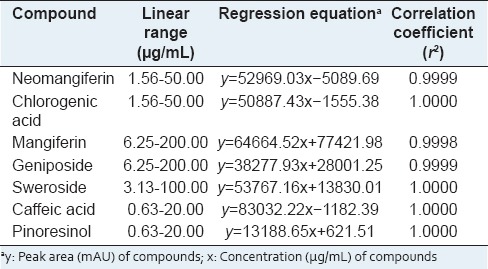

Chromatographic analysis for simultaneous determination was performed on a Shimadzu Prominence LC-20A system (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan), comprising a solvent delivery unit, online degasser, column oven, autosampler, and photodiode array (PDA) detector. The data processor used LC Solution Software (version 1.24; Shimadzu Co.). The nine constituents were separated on a Phenomenex Gemini C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and maintained at 40°C. The mobile phases comprised of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient flow was as follows: 10–60% B for 0–30 min, 60–100% B for 30–40 min, 100% B for 40–45 min, 100–10% B for 45–50 min, and 100% B for 50–60 min. The flow rate was 0.6 mL/min, and the injection volume was 10 μL. The wavelength of the PDA was 190–400 nm, and the detected wavelengths for quantitative analysis were monitored at 240 nm (neomangiferin, mangiferin, geniposide, and sweroside), 280 nm (pinoresinol), and 325 nm (chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid). All calibration curves were obtained by assessment of the peak areas from standard solutions in the following concentration ranges: Neomangiferin and chlorogenic acid, 1.56–50.00 μg/mL; mangiferin and geniposide, 6.25–200.00 μg/mL; sweroside, 3.13–100.00 μg/mL; and caffeic acid and pinoresinol, 0.63–20.00 μg/mL.

Cell culture and differentiation

The mouse 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CL-173, ATCC, Rockville, MD). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C. For adipocyte differentiation, the cells were stimulated with 3T3-L1 differentiation medium containing isobutylmethylxanthine, dexamethasone, and insulin (MDI) (Zen-Bio Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC) for 48 h after reaching a confluent state. The medium was switched to DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 μg/mL insulin after 2 days, and then changed to DMEM containing 10% FBS for an additional 4 days. YGSHT extract was added to the cell culture during the 8 days of differentiation. GW-9662 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) antagonist, was used as a positive control.

Cytotoxicity assay

Undifferentiated 3T3-L1 cells were treated with various concentrations of YGSHT for 24 h. To produce differentiated adipocyte cells, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated for 8 days with YGSHT stimulation. Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) solution (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) was added, and the cells were incubated for 4 h. After incubation, the absorbance was read at 450 nm on a microplate reader (Benchmark Plus, Bio-Rad. Hercules, CA).

Oil red O staining

Differentiated 3T3-L1 cells were fixed with 10% formalin for 15 min at room temperature and washed with 70% ethanol and PBS. The cells were stained with oil red O (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 5 min and then washed with PBS. Cell images were viewed on an Olympus CKX-41 inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Stained oil droplets were dissolved in isopropyl alcohol, and the number of droplets was quantified by reading the absorbance at 520 nm on a Benchmark Plus microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Triglyceride quantification assay

The triglyceride concentration was measured enzymatically using a commercial kit (BioVision Inc., Milpitas, CA). Briefly, 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with YGSHT were homogenized in 5% NP-40 assay buffer. The sample was heated slowly to solubilize all triglycerides and then mixed with lipase and the triglyceride reaction mixture. After 1 h incubation, the sample absorbance was measured at 570 nm on a Benchmark Plus microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity assay

GPDH activity was measured using a commercial kit (TAKARA, Tokyo, Japan) and by monitoring the dihydroxyacetone phosphate-dependent oxidation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) at 340 nm. GPDH activity was expressed as units/mg of protein.

Leptin immunoassay

The leptin concentration was measured using a mouse leptin immunoassay kit (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the supernatant was collected from the cell culture. Equal volume of the supernatant (50 μL) and Assay Diluent RD1W (50 μL) were added to a 96-well plate, and the plate was incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The plate was washed five times with 400 μL of wash buffer, 100 μL of mouse leptin conjugate was added to each well, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The plate was washed 5 times, 100 μL of substrate solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, 100 μL of stop solution was added to each well, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm on a Benchmark Plus microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

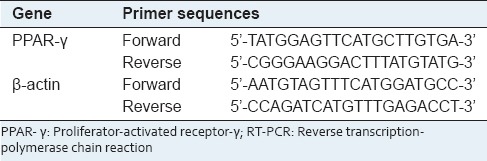

Total RNA was prepared using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and reverse-transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The expression of PPAR-γ was analyzed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using the primers listed in Table 2. RT-PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized using ChemiDoc™ XRS (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Table 2.

List of primer sequences for RT-PCR

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Group differences were assessed by One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple comparison post-hoc test using GraphPad InStat (verion3.10; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). The differences between the sample and normal control at P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Quantitative analysis of nine marker components of Yanggyuksanhwa-tang

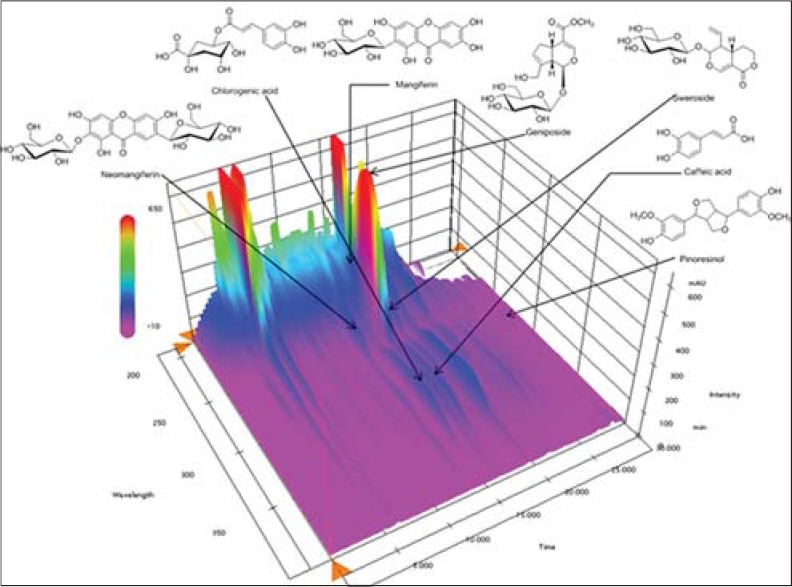

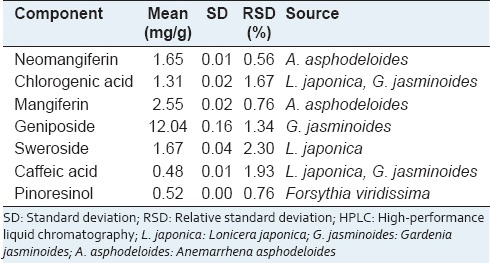

We obtained a satisfactory HPLC chromatogram using mobile phases comprising (A) 0.1% (v/v) aqueous formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B) with a gradient elution. Quantification was achieved by PDA detection from 190 to 400 nm, based on the peak area. Using optimized chromatography conditions, all analytes were separated before 30 min. The three-dimensional chromatograms of YGSHT water extract are shown in Figure 1. The calibration curves of all compounds showed good linearity with r2 ≥ 0.9998 for six different concentration ranges [Table 3]. The retention times of the seven components, neomangiferin, chlorogenic acid, mangiferin, geniposide, sweroside, caffeic acid, and pinoresinol were 13.44, 15.13, 16.37, 16.52, 16.80, 17.08, and 28.51 min, respectively. The concentrations of the seven marker compounds were in the range of 0.48–12.04 mg/g and are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional chromatogram of Yanggyuksanhwa-tang by high-performance liquid chromatography-photodiode array

Table 3.

Regression equations, linearity, and correlation coefficient for seven compounds

Table 4.

Amounts of seven components in the Yanggyuksanhwa-tang by HPLC (n=3)

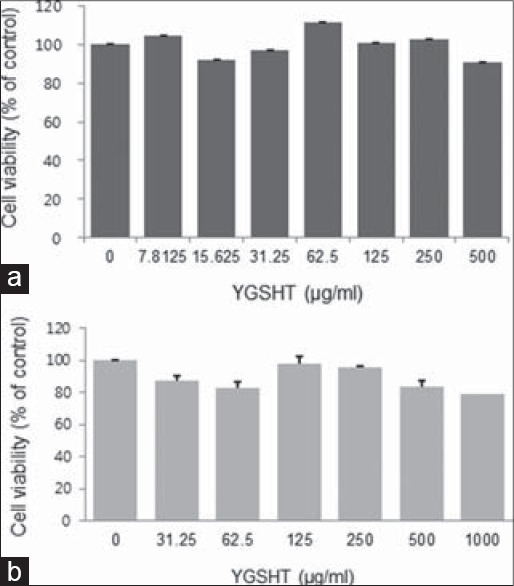

Cytotoxic effects of Yanggyuksanhwa-tang against undifferentiated and differentiated 3T3-L1 cells

The CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of YGSHT against 3T3-L1 cells. Both undifferentiated preadipocytes and differentiated adipocytes were exposed to YGSHT concentration range of 31.5–1000 μg/mL for 24 h or 8 days, respectively. As shown in Figure 1, YGSHT had no significant cytotoxic effect in preadipocytes or adipocytes.

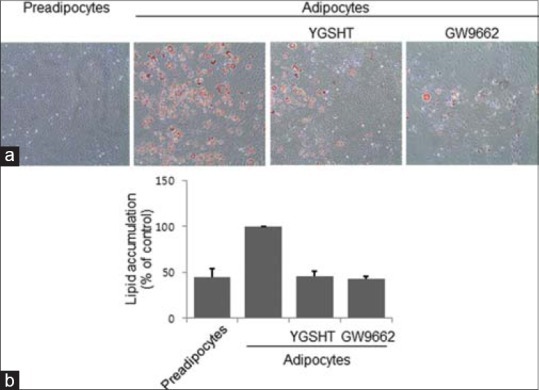

Effects of Yanggyuksanhwa-tang on adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells

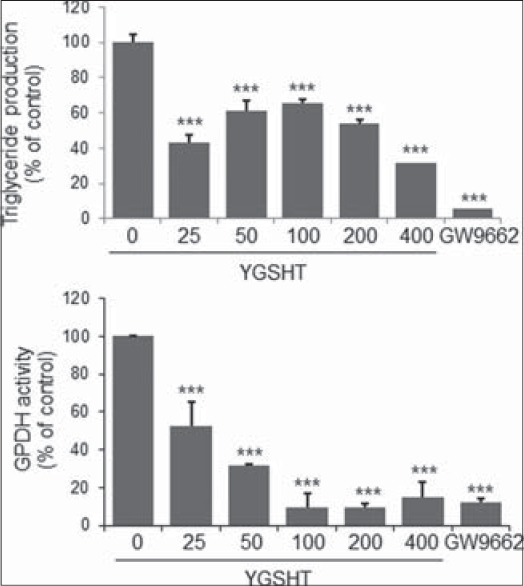

To examine the effect of YGSHT extract on triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes, we performed oil red O staining and triglyceride quantification assay. As shown in Figure 2a, the number of lipid droplets was markedly higher in differentiated adipocytes compared with the undifferentiated controls. By contrast, YGSHT exhibits an inhibitory effect on the accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets in differentiated adipocytes [Figure 2a]. To quantify the lipid accumulation, we dissolved the stained droplets in isopropyl alcohol and measured the optical density. Consistent with the data shown in Figure 2a, YGSHT-treated adipocytes exhibited significantly less lipid accumulation compared with untreated adipocytes [Figure 2b]. A significant reduction in triglyceride content was also observed in YGSHT-treated cells [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Cytotoxic effects of YGSHT extract in undifferentiated and differentiated 3T3-L1 cells. (a) 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were treated with various concentrations of YGSHT (0, 7.8125, 15.625, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, or 500 μg/ml) for 24 h. (b) 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into adipocytes by incubation with MDI for 8 days. The cells were exposed to various concentrations of YGSHT (0, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 or 1000 μg/ml) during the differentiation period. Cell viability was determined using a CCK-8 assay kit by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm. Data are presented as mean SEM

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effect of YGSHT extract on triglyceride production in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into adipocytes by incubation with MDI for 8 days. The cells were treated with or without YGSHT or GW9662 (20 μM) during the differentiation period. (A and B) Lipid accumulation in the cells was analyzed by Oil Red O staining. (a) The stained cells were visualized on an Olympus CKX41 inverted microscopy at ×200 of magnification. (b) Stained oil droplets were dissolved in isopropyl alcohol and quantified by reading the absorbance at 520 nm

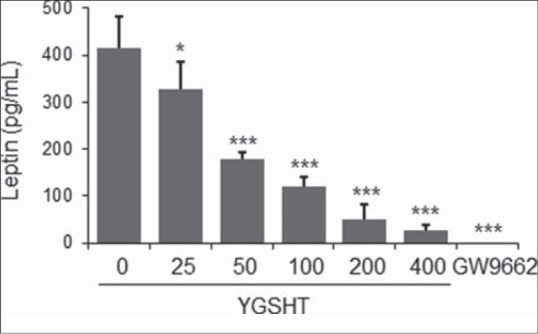

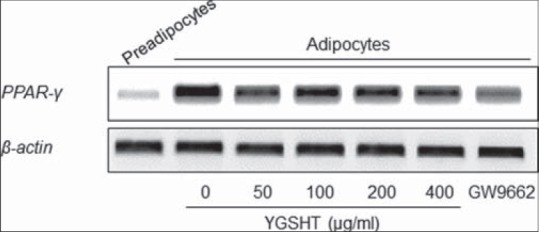

GPDH enzyme activity and leptin production were also measured to determine whether YGSHT has anti-adipogenic effects. At a concentration of 25–400 μg/mL, YGSHT extract significantly blocked the GPDH enzyme activation compared with the untreated control [Figure 3]. The amount of leptin in adipocytes was significantly reduced by YGSHT treatment in a dose-dependent manner [Figure 4]. YGSHT down-regulated the mRNA expression of PPAR-γ, a major transcription factor in adipogenesis,[9] compared with untreated adipocytes [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Inhibitory effects of YGSHT on triglyeride contents and GPDH activity in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into adipocytes by incubation with MDI for 8 days. The cells were exposed to various concentrations of YGSHT during the differentiation period. (a) The triglyceride contents were measured enzymatically using a commercial kit at 570 nm. (b) GPDH activity of the cells was assessed by measuring the decrease in NADH at 340nm using a GPDH activity assay kit. Data are presented the mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 compared with the differentiated control

Figure 5.

Inhibitory effects of YGSHT on leptin production in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into adipocytes by incubation with MDI for 8 days. Culture supernatant was collected from the YGSHT-treated cells. Leptin production was determined by ELISA by subtracting the value measured at 450 nm using a mouse leptin immunoassay kit (R&D Systems). Data are presented the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 compared with the differentiated control

The PPAR-γ inhibitor GW-9662, which served as a positive control, markedly reduced triglyceride accumulation, GPDH activity, leptin production, and PPAR-γ expression in adipocytes [Figures 2-4].

DISCUSSION

A traditional Korean herbal prescription YGSHT comprises nine herbal medicines R. glutinosa, L. japonica, F. viridissima, G. jasminoides, M. arvensis, A. asphodeloides, Gypsum, S. divaricata, and S. tenuifolia. The main constituents of these herbal medicines are as follows: Iridoid glycosides (i.e. catalpol) from R. glutinosa;[10] iridoids (i.e. sweroside) and phenolic compounds (i.e. chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid) from L. japonica;[11] iridoids (i.e. geniposide and genipin) from G. jasminoides;[12] lignans (i.e. pinoresinol) from F. viridissima;[13] monoterpenoids (i.e. menthol) from M. arvensis;[14] xanthones (i.e. mangiferin and neomangiferin) from A. asphodeloides;[15] CaSO4·2H2O from Gypsum;[16] chromones (i.e. prim-O-glucosylcimifugin) from S. divaricate;[17] and monoterpnen-ketones (i.e. [-]-pulegone) from S. tenuifolia.[18]

Using HPLC-PDA, we analyzed seven compounds among these constituents including sweroside, caffeic acid, and chlorogenic acid (L. japonica), pinoresinol (F. viridissima), geniposide, caffeic acid, and chlorogenic acid (G. jasminoides), and mangiferin and neomangiferin (A. asphodeloides). The established HPLC–PDA method was applied for the simultaneous analysis of the seven compounds in YGSHT, whose contents were found in the range of 0.48–12.04 mg/g. Geniposide (12.04 mg/g), a marker compound of G. jasminoides, was detected as the main component with the others in this sample [Figure 1]. The established HPLC–PDA method will be helpful for improving the quality control of YGSHT.

Of the nine herbal components of YGSHT, five herbs R. glutinosa, G. jasminoides, A. asphodeloides, M. arvensis, and Gypsum have been reported to have biological activity against obesity and obesity-related diseases.[19,20,21,22,23] However, the anti-obesity effects of YGSHT, a mixture of these medicinal herbs, have not been reported. In the present study, we investigated the anti-adipogenic activity of YGSHT. Adipogenesis is the process by which preadipocytes differentiate into adipocytes.[24] In an experimental model, preadipocytes can be differentiated by stimulation with a combination of adipogenic effectors such as MDI.[25] Currently, 3T3-L1 preadipocyte is considered to be the most useful cells for studying adipocytes.[26] We induced cellular differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells from preadipocytes into adipocytes. YGSHT was not cytotoxic to preadipocytes or adipocytes [Figure 6]. Adipocytes play an essential role in energy homeostasis by acting as an energy reserve for triglyceride.[27] Oil red O staining was used to visualize lipid droplets containing the triglyceride in differentiated adipocytes. YGSHT extract markedly decreased the number of lipid droplets compared with untreated control adipocytes [Figure 2a and b]. Consistent with this observation, the content of triglyceride was also significantly reduced by YGSHT extract [Figure 2c].

Figure 6.

Effects of Yanggyuksanhwa-tang (YGSHT) on the mRNA expression of PPAR-γ in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into adipocytes by incubation with isobutylmethylxanthine, dexamethasone and insulin (MDI) for 6 days. The cells were exposed to various concentrations of YGSHT (0, 50, 100, 200, or 400 μg/ml) during the differentiation period. Total RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR for PPAR-γ. β-actin was used as a housekeeping gene

GPDH is a key enzyme in adipogenesis. GPDH activity increases rapidly during maturation from preadipocytes to mature adipocytes through the reduction of dihydroxyacetone phosphate to glycerol 3-phosphate using coenzyme NAD.[28] In our study, YGSHT extract significantly inactivated the GPDH enzyme in adipose cells [Figure 3]. The extent of inhibition by YGSHT was equivalent to that of GW-9662, which was used as a positive control. Adipokines, also called adipocytokines, are cytokines secreted by the adipocytes in adipose tissue. Leptin, a major adipokine, is produced primarily in the adipocytes of white adipose tissue and its main function is in the regulation of fat storage as an adaptive response in the control of energy balance.[29] With ghrelin, an adipokine that has an opposite function to that of leptin,[30] leptin participates in the complex process of energy homeostasis. In our study, YGSHT extract significantly reduced the production of leptin in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes [Figure 4]. Adipogenesis is tightly regulated by a cascade of several transcriptional factors,[31] of which PPAR-γ is the main transcriptional factor that is indispensable for adipocyte differentiation.[9] Decreased expression of PPAR-γ was detected at the mRNA level in YGSHT-treated adipocytes.

CONCLUSION

YGSHT inhibited fat accumulation in adipocytes and reduced triglyceride production. YGSHT decreased GPDH activity and the level of leptin in adipose cells. In addition, YGSHT suppressed the mRNA expression of PPAR-γ, a major transcriptional factor in adipogenesis. Collectively, these findings support the potential of YGSHT as an anti-adipogenic agent in an experimental model. It may be possible to use YGSHT as an anti-obesity functional material. Additional studies will be needed to confirm the anti-obesity effects of YGSHT in an in vivo model and to identify the regulatory molecular mechanisms responsible for the anti-obesity effects of YGSHT.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation (WHO Technical Report Series 894) 2000:16–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366:1197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Najafian J, Abdar-Esfahani M, Arab-Momeni M, Akhavan-Tabib A. Safety of herbal medicine in treatment of weight loss. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014;10:55–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han Y, Jung HW, Bae HS, Park YK. Wen-pi-tang-Hab-Wu-ling-san, a Polyherbal Medicine, Attenuates ER Stress in 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes by Promoting the Insulin Signaling Pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/825814. 825814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikarashi N, Tajima M, Suzuki K, Toda T, Ito K, Ochiai W, et al. Inhibition of preadipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation by Orengedokuto treatment of 3T3-L1 cultures. Phytother Res. 2012;26:91–100. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwak DH, Lee JH, Kim DG, Kim T, Lee KJ, Ma JY. Inhibitory Effects of Hwangryunhaedok-Tang in 3T3-L1 Adipogenesis by Regulation of Raf/MEK1/ERK1/2 Pathway and PDK1/Akt Phosphorylation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/413906. 413906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong HJ, Lee HJ, Hong SH, Kim HM, Um JY. Inhibitory effect of Yangkyuk-Sanhwa-Tang on inflammatory cytokine production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the cerebral infarction patients. Int J Neurosci. 2007;117:525–37. doi: 10.1080/00207450600773590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong HJ, Hong SH, Park HJ, Kweon DY, Lee SW, Lee JD, et al. Yangkyuk-Sanhwa-Tang induces changes in serum cytokines and improves outcome in focal stroke patients. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;39:63–8. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farmer SR. Regulation of PPARgamma activity during adipogenesis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29(Suppl 1):S13–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang WT, Choi YH, Van der Heijden R, Lee MS, Lin MK, Kong H, et al. Traditional processing strongly affects metabolite composition by hydrolysis in Rehmannia glutinosa roots. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2011;59:546–52. doi: 10.1248/cpb.59.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian ZM, Li HJ, Li P, Chen J, Tang D. Simultaneous quantification of seven bioactive components in Caulis Lonicerae japonicae by high performance liquid chromatography. Biomed Chromatogr. 2007;21:649–54. doi: 10.1002/bmc.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee IA, Lee JH, Baek NI, Kim DH. Antihyperlipidemic effect of crocin isolated from the fructus of Gardenia jasminoides and its metabolite Crocetin. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:2106–10. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HY, Kim JK, Choi JH, Jung JY, Oh WY, Kim DC, et al. Hepatoprotective effect of pinoresinol on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic damage in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;112:105–12. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09234fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho H, Sowndharrajan K, Jung JW, Jhoo JW, Kim S. Fragrance chemicals in the essential oil of Mentha arvensis reduce levels of mental stress. J Life Sci. 2013;23:933–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu L, Li A, Sun A, Liu R. Preparative isolation of neomangiferin and mangiferin from Rhizoma anemarrhenae by high-speed countercurrent chromatography using ionic liquids as a two-phase solvent system modifier. J Sep Sci. 2010;33:31–6. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korea Food and Drug Administration. The Korean Herbal Pharmacopoeia. Dongwon Munhwasa. 2007:196. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim MK, Yang DH, Jung M, Jung EH, Eom HY, Suh JH, et al. Simultaneous determination of chromones and coumarins in Radix Saposhnikoviae by high performance liquid chromatography with diode array and tandem mass detectors. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:6319–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.06.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chun MH, Kim EK, Lee KR, Jung JH, Hong J. Quality control of Schizonepeta tenuifolia Briq by solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and principal component analysis. Microchem J. 2010;95:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SM, Hong SM, Sung SR, Lee JE, Kwon DY. Extracts of Rehmanniae radix, Ginseng radix and Scutellariae radix improve glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and beta-cell proliferation through IRS2 induction. Genes Nutr. 2008;2:347–51. doi: 10.1007/s12263-007-0065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kojima K, Shimada T, Nagareda Y, Watanabe M, Ishizaki J, Sai Y, et al. Preventive effect of geniposide on metabolic disease status in spontaneously obese type 2 diabetic mice and free fatty acid-treated HepG2 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:1613–8. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miura T, Ichiki H, Iwamoto N, Kato M, Kubo M, Sasaki H, et al. Antidiabetic activity of the rhizoma of Anemarrhena asphodeloides and active components, mangiferin and its glucoside. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:1009–11. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie W, Zhao Y, Gu D, Du L, Cai G, Zhang Y. Scorpion in combination with Gypsum: Novel antidiabetic activities in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice by up-regulating pancreatic PPAR? and PDX-1 Expressions. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1093/ecam/neq031. 683561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motoyama H, Enomoto M, Yasuda T, Fujii H, Kobayashi S, Iwai S, et al. Drug-induced liver injury caused by an herbal medicine, bofu-tsu-sho-san. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;105:1234–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacDougald OA, Lane MD. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression during adipocyte differentiation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:345–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkland JL, Hollenberg CH, Gillon WS. Age, anatomic site, and the replication and differentiation of adipocyte precursors. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:C206–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.2.C206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green H, Meuth M. An established pre-adipose cell line and its differentiation in culture. Cell. 1974;3:127–33. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornelius P, MacDougald OA, Lane MD. Regulation of adipocyte development. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14:99–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozak LP, Jensen JT. Genetic and developmental control of multiple forms of L-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7775–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers MG, Jr, Münzberg H, Leinninger GM, Leshan RL. Cell Metab. 2009. The geometry of leptin action in the brain: More complicated than a simple ARC; pp. 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennan AM, Mantzoros CS. Drug Insight: The role of leptin in human physiology and pathophysiology – Emerging clinical applications. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:318–27. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowherd RM, Lyle RE, McGehee RE., Jr Molecular regulation of adipocyte differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1999;10:3–10. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]