Abstract

Background:

Annona vepretorum (AV) is a native tree from Caatinga biome (semiarid region of Brazil) popularly known as “araticum” and “pinha da Caatinga.”

Objective:

This study was carried out to evaluate the chemical constituents and antioxidant activity (AA) of the essential oil from the leaves from AV (EO-Av) collected in Petrolina, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Materials and Methods:

Fresh leaves of AV were cut into pieces, and subjected to distillation for 2 h in a clevenger-type apparatus. Gas chromatograph (GC) analyses were performed using a mass spectrometry/flame ionization detector. The identification of the constituents was assigned on the basis of comparison of their relative retention indices. The antioxidant ability of the EO was investigated through two in vitro models such as radical scavenging activity using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl method and β-carotene-linoleate-model system. The positive controls (ascorbic acid, butylated hydroxyanisole and butylated hydroxytoluene) were those using the standard solutions. Assays were carried out in triplicate.

Results:

The oil showed a total of 21 components, and 17 were identified, representing 93.9% of the crude EO. Spathulenol (43.7%), limonene (20.5%), caryophyllene oxide (8.1%) and α-pinene (5.5%) were found to be the major individual constituents. Spathulenol and caryophyllene oxide could be considered chemotaxonomic markers of these genera. The EO demonstrated weak AA.

Keywords: Annona vepretorum, annonaceae, antioxidant activity, essential oil

INTRODUCTION

Annonaceae is a pantropical family of trees, shrubs and lianas. They play an important ecological role in terms of species diversity, especially in tropical rainforest ecosystems. Until date, there are 109 validly described and recognized genera and about 2440 species.[1] Chemical studies with species of this family have reported the isolation of terpenoids (mainly diterpenes), essential oils (EO) which the composition is predominantly of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, and alkaloids, especially isoquinoline alkaloids.[2]

Annona L. belongs to the Annonaceae family and comprises approximately 175 species of trees and shrubs. Economically, this genus is the most important of the Annonaceae family due to its edible fruits and medicinal properties.[3] Several Annona species furnish edible fruits, some of them very much appreciated in Brazil, such as Annona crassiflora Mart. (“araticum”), Annona squamosa L. (“fruta do conde”) and Annona muricata L. (“graviola”). The fruits are usually consumed “in natura” or used in juices, desserts or ice-cream preparations.[4] In our continuous search for identification of compounds from species of the Annonaceae family from Northeastern Brazil, this study reports the analysis of the chemical composition of the essential from leaves of Annona vepretorum (AV).

This species is endemic to Brazil (Caatinga biome) and is popularly known as “pinha da Caatinga”.[5] Its fruits are consumed raw or in juice form as a nutritional source. When softened, its roots present popular medicinal indication to bite of bees and snakes, inflammatory conditions and pains in the heart, while the leaves (decoction) are used in bath to allergies, skin diseases, yeast and bacterial infection.[6] Previous study on this species described the composition and the bioactivity (trypanocidal, antifungal and antioxidant properties) of the EO from the leaves collected in Poço Redondo, state of Sergipe, Brazil.[7] Recently, our research group evaluated the central nervous system effects of the ethanolic extract in mice and demonstrated that this plant has sedative activity[8] as well as antioxidant, cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities.[9] A novel ent-kaurane diterpene, ent-3 β-hydroxy-kaur-16-en-19-al along with five known ent-kaurane diterpenes, ent-3 β,19-dihydroxy-kaur-16-ene, ent-3 β-hydroxy-kaur-16-ene, ent-3 β-acetoxy-kaur-16-ene, ent-3 β-hydroxy-kaurenoic acid and kaurenoic acid, as well as caryophyllene oxide, humulene epoxide II, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol and campesterol were isolated from the stem bark of AV.[6]

In this paper, the EO of the fresh leaves from AV collected in Petrolina (Pernambuco, Brazil) was obtained and analyzed by gas chromatograph-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Evaluation of in vitro antioxidant activity (AA) was also performed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

The leaves of AV were collected in January 2012, in the City of Petrolina, State of Pernambuco, Brazil. The voucher sample (#3161) was deposited in the Herbarium Vale do São Francisco (HVASF) from Federal University of San Francisco Valley.

Hydrodistillation of the volatile constituents

Fresh leaves of AV (728.0 g) were cut into pieces and subjected to distillation for 2 h in a Clevenger-type apparatus. The oil was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and their percentage content was calculated on the basis of the dry weight of plant material. The EO obtained (0.0957% w/w) is colorless and has a characteristic odor. The oil was kept in amber bottle flask and maintained in temperature lower than 4°C.

Analysis of the essential oil (essential oil from the leaves of Annona vepretorum) by gas chromatograph and gas chromatograph/mass spectrometry

Gas chromatograph (GC) analyses were performed using a MS/flame ionization detector (GC-MS/FID) (QP2010 Ultra, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an autosampler AOC-20i (Shimadzu). Separations were accomplished using an Rtx®-5MS Restek fused silica capillary column (5%-diphenyl-95%-dimethyl polysiloxane) of 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness, at a constant helium (99.999%) flow rate of 1.2 ml/min. Injection volume of 0.5 μL (5 mg/ml) was employed, with a split ratio of 1:10. The oven temperature was programmed from 50°C (isothermal for 1.5 min), with an increase of 4°C/min, to 200°C, then 10°C/min to 250°C, ending with a 5 min isothermal at 250°C. The MS and FID data were simultaneously acquired employing a Detector Splitting System; the split flow ratio was 4:1 (MS: FID). A 0.62 m × 0.15 mm i.d. restrictor tube (capillary column) was used to connect the splitter to the MS detector; a 0.74 m × 0.22 mm i.d. restrictor tube was used to connect the splitter to the FID detector. The MS data (total ion chromatogram) were acquired in the full scan mode (m/z of 40–350) at a scan rate of 0.3 scan/s using the electron ionization (EI) with an electron energy of 70 eV. The injector temperature was 250°C and the ion-source temperature was 250°C. The FID temperature was set to 250°C, and the gas supplies for the FID were hydrogen, air, and helium at flow rates of 30, 300, and 30 ml/min, respectively. Quantification of each constituent was estimated by FID peak-area normalization (%). Compound concentrations were calculated from the GC peak-areas, and they were arranged in order of GC elution.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis

The data were acquired and processed with a PC with Shimadzu GC-MS-Solution software. The identification of the constituents was assigned on basis of comparison of their relative retention indices[10] to a n-alkane homologous series (nC9-nC19) obtained by co-injecting the oil sample with a linear hydrocarbon mixture, as well as, by computerized matching of the acquired mass spectra witch those stored in Wiley 8 and NIST05 mass spectral libraries of the GC-MS data system and other published mass spectra.[11,12]

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl free radical scavenging assay

The free radical scavenging activity was measured using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazil (DPPH) assay.[13] Sample stock solution (1.0 mg/ml) of the EO was diluted to final concentrations of 243, 81, 27, 9, 3 and 1 μg/ml, in ethanol. A volume of 1 ml of a 50 μg/ml DPPH ethanol solution was added to 2.5 ml of sample solutions of different concentrations and allowed to react at room temperature. After 30 min the absorbance values were measured at 518 nm and converted into the percentage AA using the following formula: AA% = ([absorbance of the control − absorbance of the sample]/absorbance of the control) × 100. Ethanol (1.0 ml) plus EO solutions (2.5 ml) were used as a blank. DPPH solution (1.0 ml) plus ethanol (2.5 ml) was used as a negative control. The positive controls (ascorbic acid, butylated hydroxyanisole [BHA] and butylated hydroxytoluene [BHT]) were those using the standard solutions. Assays were carried out in triplicate.

β-carotene bleaching test

The β-carotene bleaching method is based on the loss of the yellow color of β-carotene due to its reaction with radicals formed by linoleic acid oxidation in an emulsion.[14] The rate of β-carotene bleaching can be slowed down in the presence of antioxidants. β-carotene (2 mg) was dissolved in 10 ml chloroform and to 2 ml of this solution, linoleic acid (40 mg) and Tween 40 (400 mg) were added. Chloroform was evaporated under vacuum at 40°C and 100 ml of distilled water was added, then the emulsion was vigorously shaken during 2 min. Reference compounds (ascorbic acid, BHA and BHT) and sample EO was prepared in ethanol. The emulsion (3.0 ml) was added to a tube containing 0.12 ml of solutions 1 mg/ml of reference compounds and sample EO. The absorbance was immediately measured at 470 nm and the test emulsion was incubated in a water bath at 50°C for 120 min, when the absorbance was measured again. Ascorbic acid, BHA and BHT were used as a positive control. In the negative control, the EO was substituted with an equal volume of ethanol. The AA (%) was evaluated in terms of the bleaching of the β-carotene using the following formula: % AA = (1−[A0-At]/[A00-At0]) × 100, where A0 is the initial absorbance and At is the final absorbance measured for the test sample, A0 0 is the initial absorbance and At0 is the final absorbance measured for the negative control (blank). The results were expressed as percentage of AA (% AA). Tests were carried out in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All determinations were conducted in triplicates and the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation values were considered significantly different at P < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

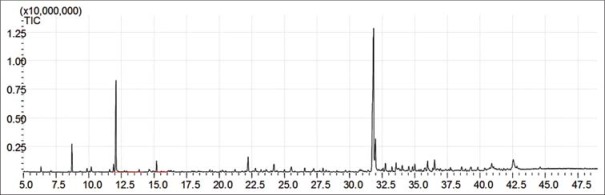

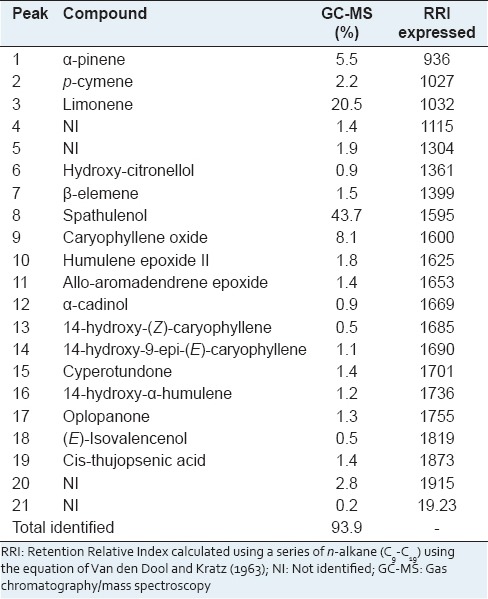

The yield of AV EO was (0.0957%). Altogether, 93.9% of the chemical constituents of the EO were identified. As observed in the chromatogram shown in Figure 1 as well as in Table 1, the oil showed a total of 21 components, and 17 were identified. Spathulenol (43.7%), limonene (20.5%), caryophyllene oxide (8.1%) and α-pinene (5.5%) were found to be the major individual constituents. In addition to the major constituents, p-cymene, β-elemene, and humulene epoxide II have been reported in EOs of several other species of Annona, indicating that this species is typically of the Annonaceae family.[7]

Figure 1.

Total ion chromatogram of chemical constituents of essential oil from Annona vepretorum leaves

Table 1.

Essential oil composition from the leaves of Annona vepretorum

Spathulenol and caryophyllene oxide have been found to be components of EOs from the leaves of several genera of Annonaceae, including Annona, and could be considered chemotaxonomic markers of these genera.[3,15] The results found in this work for AV cultivated in Petrolina, differ from that presented in the literature, where the bicyclogermacrene (43.7%) and spathulenol (11.4%) appear as major components.[7] What can be understood when considering that the environment of which the plant develops are factors such as temperature, relative humidity, exposure to the sun and wind, which exert a direct influence on the chemical composition of volatile oils.[16] Composition of the essential oils can vary with the climate, geographical area, seasons, soil conditions, crop period, and isolation technique.[17] It is worth mentioning that spathulenol is present in the essential oil of several species and has shown antimicrobial, antiulcer, anti-inflammatory and spasmolytic activities.[18]

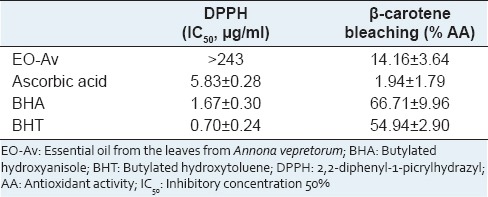

In the present study, the antioxidant ability of the essential oil was investigated through two in vitro models such as radical scavenging activity using, DPPH method, and β-carotene-linoleate model system. Table 2 summarizes the results of the effect of essential oil from AV, ascorbic acid, BHA and BHT on the DPPH free radical scavenging and β-carotene-linoleic acid bleaching test. The essential oil demonstrated weak AA in the two models assayed.

Table 2.

Antioxidant activity of the EO-Av and standards ascorbic acid, BHA and BHT

CONCLUSION

AV is a rich source of volatile constituents, mainly of spathulenol, which was the majority constituent of the essential oil. However, the essential oil demonstrated weak AA in the models used in this work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chatrou LW, Pirie MD, Erkens RH, Couvreur TL, Neubig KM, Abbott RJ, et al. A new higher-level classification of the pantropical flowering plant family Annonaceae informed by molecular phylogenetics. Bot J Linn Soc. 2012;169:5–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva MS, Tavares JF, Queiroga KF, Agra MF, Barbosa-Filho JM, Almeida JR, et al. Alkaloids and other constituents from Xylopia langsdorffiana (Annonaceae) Quim Nova. 2009;32:1566–70. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutra LM, Costa EV, Moraes VR, Nogueira PC, Vendramin ME, Barison A, et al. Chemical constituents from the leaves of Annona pickelii (Annonaceae) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2012;41:115–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lima LA, Pimenta LP, Boaventura MA. Acetogenins from Annona cornifolia and their antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2010;122:1129–38. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maas P, Rainer H, Lob o A. Annonaceae in List of Species of Brazilian Flora. Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden. 2010. [Last access in 2015 Mar 16]. Available from: http://www.floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/2010/FB117277 .

- 6.Dutra LM, Bomfim LM, Rocha SLA, Nepel A, Soares MBP, Barison A, et al. Ent-Kaurane diterpenes from the stem bark of Annona vepretorum (Annonaceae) and cytotoxic evaluation. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:3315–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa EV, Dutra LM, Nogueira PC, Moraes VR, Salvador MJ, Ribeiro LH, et al. Essential oil from the leaves of Annona vepretorum: Chemical composition and bioactivity. Nat Prod Commun. 2012;7:265–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diniz TC, Araújo CS, Silva JC, Oliveira-Júnior RG, Lima-Saraiva SRG. Phytochemical screening and central nervous system effects of ethanolic extract of Annona vepretorum (Annonaceae) in mice. J Med Plant Res. 2013;7:2729–35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almeida JRGS, Araújo CS, Pessoa CO, Costa MP, Pacheco AGM. Antioxidant, cytotoxic and Antimicrobial activity of Annona vepretorum Mart. (Annonaceae) Rev Bras Frutic. 2014;36:258–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandendool H, Kratz PD. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1963;11:463–71. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80947-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams RP. 4th ed. USA: Allured Publishing Corporation Carol Stream, IL; 2007. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams RP, Nguyen S, Johnston DA, Park S, Provin TL, Habte M. Comparation of vetiver root essential oils from cleansed (bacteria-and fungus-free) vs. non-cleansed (normal) vetiver plants. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2008;36:177–82. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva ME, Guimarães AL, Oliveira AP, Araújo CS, Siqueira-Filho JA, Fontana AP, et al. HPLC-DAD analysis and antioxidant activity of Hymenaea martiana Hayne (Fabaceae) J Chem Pharm Res. 2012;4:1160–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aidi Wannes W, Mhamdi B, Sriti J, Ben Jemia M, Ouchikh O, Hamdaoui G, et al. Antioxidant activities of the essential oils and methanol extracts from myrtle (Myrtus communis var. italica L.) leaf, stem and flower. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:1362–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz PE, Costa EV, Moraes VR, Nogueira PC, Vendramin ME, Barison A, et al. Chemical constituents from the bark of Annona salzmannii (Annonaceae) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2011;39:872–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Morais SR, Oliveira TL, Bara MT, da Conceição EC, Rezende MH, Ferri PH, et al. Chemical constituents of essential oil from Lippia sidoides Cham. (Verbenaceae) leaves cultivated in Hidrolândia, Goiás, Brazil. Int J Anal Chem 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/363919. 363919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvalho-Filho JL, Blank AF, Alves PB, Ehlert PA, Melo AS, Cavalcanti SC, et al. Influence of the harvesting time, temperature and drying period on basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) essential oil. Braz J Pharmacogn. 2006;16:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez-Hernandez N, Ponce-Monter H, Medina JA, Joseph-Nathan P. Spasmolytic effect of constituents from Lepechinia caulescens on rat uterus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115:30–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]