Abstract

Objective. The purpose of this study is to describe the impact of depression on perceptions of risks to health, diabetes self-management practices, and glycemic control in older African Americans with type 2 diabetes.

Methods. The authors analyzed data on depression, risk perceptions, diabetes self-management, and A1C in African Americans with type 2 diabetes. T-tests, χ2, and multivariate regression were used to analyze the data.

Results. The sample included 177 African Americans (68% women) whose average age was 72.8 years. Thirty-four participants (19.2%) met criteria for depression. Compared to nondepressed participants, depressed participants scored significantly higher on Personal Disease Risk (the perception of being at increased risk for various medical problems), Environmental Risk (i.e., increased risk for environmental hazards), and Composite Risk Perception (i.e., overall perceptions of increased risk); adhered less to diabetes self-management practices; and had marginally worse glycemic control. Depression and fewer years of education were independent predictors of overall perception of increased health risks.

Conclusion. Almost 20% of older African Americans with type 2 diabetes in this study were depressed. Compared to nondepressed participants, they tended to have fewer years of education, perceived themselves to be at higher risk for multiple health problems, and adhered less to diabetes self-management practices. It is important for diabetes educators to recognize the impact of low education and the fatalistic perceptions that depression engenders in this population.

The relationship between diabetes and depression is complex and bidirectional.1,2 Depression reduces physical activity, fosters unhealthy diets, depletes motivation to self-manage health, and activates neuroendocrine and inflammatory pathways that increase insulin resistance.3,4 Diabetes requires major lifestyle changes, carries a high risk of medical complications, and is associated with structural brain changes, all of which may cause depression.5–7

These considerations are important to older African Americans who, compared to whites, have almost twice the rate of type 2 diabetes, worse glycemic control, and equivalent or higher rates of depression.8–10 In fact, about 25% of African Americans with type 2 diabetes have clinically significant depression, but they are less likely than whites to seek treatment because of misconceptions about depression, stigma, and limited access to culturally relevant care.11–14 For these patients, untreated depression adds to disparities in education, health literacy, and socioeconomic resources and may explain why African Americans are more likely than whites to go blind, lose limbs, need dialysis, and die from diabetes.15–17

Perceptions of risk for developing these adverse outcomes influence diabetes self-management and the actual risk of developing diabetes complications. Drawing from health belief theories, risk perception invokes the concepts of perceived susceptibility (one’s chances of experiencing a disease), perceived severity, perceived benefits (efficacy of the advised action to reduce risk), perceived barriers, cues to action (strategies to activate “readiness”), and self-efficacy.18 Perceptions of risk may be influenced by depression, which distorts one’s sense of self-efficacy and view of the future and induces fatalistic perspectives on the preventability of diabetes complications and other health threats.

In this study, we compared depressed and nondepressed older African Americans with type 2 diabetes to assess the impact of depression on risk perceptions, diabetes self-management practices, and glycemic control. Understanding these relationships may inform new interventions to improve glycemic control and prevent diabetes complications in this population.

Methods

Participants (n = 177) are enrolled in an ongoing randomized, controlled clinical trial that compares the efficacy of Behavior Activation (active treatment) to Supportive Therapy (control condition) to increase rates of dilated fundus examinations in older African Americans with type 2 diabetes.19 Data reported here were obtained at the baseline assessment before randomization.

Community health workers (CHWs) who were concordant in language, race, and ethnicity recruited participants from community sites and the primary care medical practices of Thomas Jefferson University and Temple University in Philadelphia, Pa., to identify African Americans > 65 years of age with physician-diagnosed type 2 diabetes and no documented dilated fundus examination in the preceding year. Exclusion criteria included cognitive impairment on an abbreviated Mini-Mental Status Examination, psychiatric disorder other than depression or anxiety, need for dialysis, and sensory impairment that precluded research participation.

The 177 participants were drawn from among 197 potentially eligible patients. The 20 patients who did not enroll did not differ in age or sex from enrolled participants. One patient was excluded because of a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

The CHWs made in-home visits to review the study, confirm eligibility, and conduct the baseline assessments. All participants signed an informed consent form approved by the institutional review boards of Jefferson and Temple. The CHWs also measured participants’ A1C using a portable measurement device and administered the following instruments:

1. Risk Perception Survey–Diabetes Mellitus (RPS-DM). The RPS-DM is a 26-item self-rated instrument that assesses perceived control over (i.e., Personal Control subscale), worry about, and likelihood of developing diabetes complications (e.g., vision loss and renal failure).20 It also includes a Personal Disease Risk subscale, which assesses perceived risk of developing nine medical conditions (e.g., myocardial infarction and stroke), and an Environmental Risk subscale, which assesses perceived risk of nine potential environmental hazards (e.g., pollution, crime, and riding in a car). A Composite Risk Perception score averages the scores of the 26 items. The RPS-DM also has a 5-item Diabetes Risk Knowledge subscale that is not included in the composite score. Responses on the RPS-DM are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly agree” to 4 = “strongly disagree.” Average item scores range from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating more perceived risk. The RPS-DM subscales and composite score have demonstrated reliability and validity.20

2. Diabetes Self-Care Inventory–Revised (DSCI-R). The DSCI-R is a 14-item self-report measure of adherence to diabetes self-care practices that has established reliability and validity, correlates with A1C levels, and is responsive to treatment.21 Items include blood glucose monitoring, medication use, exercise, diet, and attending clinic appointments. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “never do this” to 5 = “always do this as recommended.” Scores are averaged and converted to a point scale of 0–100, with higher scores indicating greater adherence during the preceding month.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is a structured instrument with known reliability and validity that includes the nine criteria that comprise diagnoses of depressive disorders in the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.22 The PHQ-9 yields both categorical diagnoses and a continuous measure of depressive symptoms and has been validated in the African-American population.23 Each of the nine depressive symptoms is scored from 0 = “not at all” to 3 “nearly every day,” yielding a range from 0 to 27. Scores ≥10 indicate clinically significant depressive symptoms with an 88% sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of a depressive disorder.22 We used this cut-off score to designate participants with clinically significant depression.

Statistical analyses

The demographic and clinical characteristics of depressed and nondepressed participants were compared using χ2 analyses for categorical data and one-way analysis of variance for continuous data. Multiple regression analysis was used to determine whether depression, defined as a PHQ-9 score ≥ 10, was related to Composite Risk Perception after controlling for age, education, sex, and A1C level.

Results

The sample included 177 African Americans with type 2 diabetes, of whom 68.0% were women. The average age (standard deviation) of participants was 72.8 (6.1) years. Thirty-four participants (19.2%) met the criteria for clinically significant depression. Thirty-three of them (97.1%) had moderate depression (i.e., PHQ-9 scores from 10 to 20); one participant had severe depression (i.e., PHQ-9 score > 20).

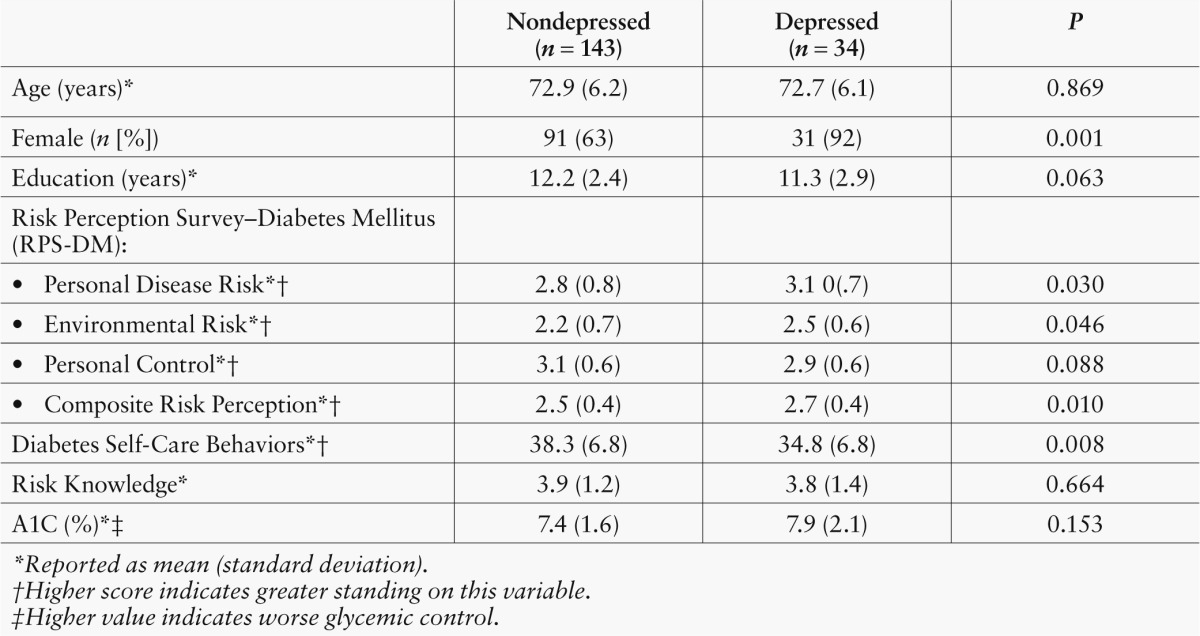

Table 1 compares depressed and nondepressed participants and shows that a higher proportion of depressed participants were women and that depressed participants tended to have fewer years of education. Depressed participants also scored significantly higher on Personal Disease Risk (indicating their perception of being at increased risk for various medical problems), Environmental Risk (i.e., increased risk for various environmental hazards), and Composite Risk Perception (i.e., overall perceptions of increased risk). Depressed participants scored significantly lower on the Diabetes Self-Care Inventory (indicating lower levels of adherence to diabetes self-management practices) and tended to score lower on Personal Control (indicating their perception of limited control over whether they develop diabetes complications). There was a trend for depressed participants to have higher A1C levels, suggesting worse glycemic control.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Depressed and Nondepressed Participants (n = 177)

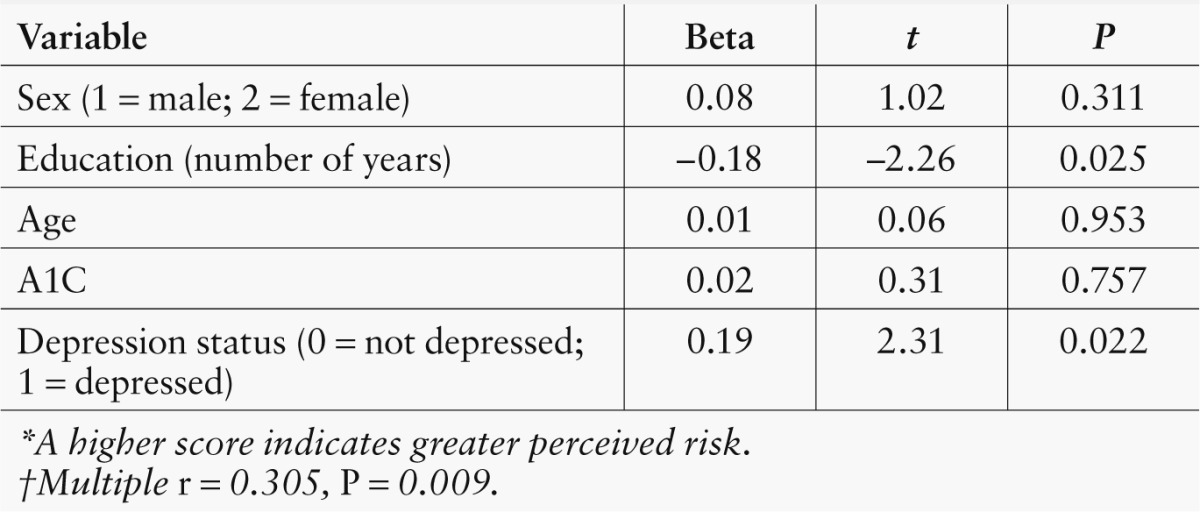

Table 2 shows the results of a multiple regression analysis examining the relationship of participants’ demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, and education), glycemic control (i.e., A1C level), and depression status to total risk perception (i.e., Composite Risk Perception score). Perceived risk was higher for depressed participants (t = 2.31, P ≤ 0.022) and those with fewer years of education (t = –2.26, P ≤ 0.025). The other demographic characteristics and A1C level were not independent predictors of perceptions of risk.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression of Total Perceived Risk*†

Discussion

We found that almost 20% of older African Americans with type 2 diabetes in this study were depressed. Compared to their nondepressed peers, they perceived themselves to be at higher risk for multiple health problems and are, in fact, at higher risk for diabetes complications because they adhere less to diabetes self-management practices. Depressed participants also perceived themselves to be at higher risk for other medical problems and environmental hazards, suggesting a global negative outlook on multiple domains of their lives.

Besides depression, having fewer years of education was associated with greater perceptions of risk to one’s health. Low education may reflect low health literacy (i.e., the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information) and may prevent accurate health appraisals. This may lead to both over- and underestimations of health risks, although, in this sample, we found higher estimations of risk. These findings agree with other studies reporting high rates of depression and low health literacy in older African Americans with diabetes, as well as higher depression rates in women and worse diabetes self-management practices, glycemic control, and medical outcomes in people with depression and fewer years of education.8,13,24–28

There are two notable limitations of our study. First, the sample is not representative of older African Americans in general, given that participants were drawn primarily from primary care medical practices, had not had dilated fundus examinations in the preceding year, and met other eligibility criteria. Our results, therefore, require replication in more representative population-based samples. Second, we relied on participants’ self-report of diabetes self-management practices, which has inherent bias and may be further affected by depression. This bias would tend to reduce the strength of associations with glycemic control.

These limitations notwithstanding, the study has a number of strengths, including its relatively large sample size, systematic assessments using standardized instruments, and the new associations we found between risk perceptions, diabetes self-management, and depression in older African Americans. These associations highlight the diversity within this population and the impact of depression on health perceptions and behaviors.

People with depression tend to hold pessimistic views of themselves and their circumstances. These views, coupled with loss of interest, low self-efficacy, and low motivation levels, compromise diabetes self-management and increase the risk for adverse health outcomes.5,6 The Health Belief Model, which posits that health beliefs predict one’s actions to maintain health, may not account for depression’s impact on expected health attitudes and behaviors.18 For this reason, other aspects of health behavior theories are needed to incorporate the influence of depression.

Behavioral psychology theory suggests that depression results from low rates of positive reinforcement for adaptive behaviors, wherein negative interactions with the environment degrade one’s ability to adapt effectively to life circumstances.29 We hypothesize that poor diabetes self-management in the context of depression reflects the absence of immediate reinforcement for desired behaviors (e.g., health benefits require years to accrue) and the immediate presence of aversive experiences (e.g., pain from finger-sticks to check blood glucose levels). This view suggests that linking diabetes self-management behaviors to positive reinforcers may achieve better glycemic control and help in treating depression.

The population is aging, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing rapidly, and our society is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse.15 For older African Americans, who comprise one of the fastest-growing minorities, depression and diabetes are diagnosed at more advanced stages compared to whites, when outcomes are less promising and care is more costly.15,30,31 These facts necessitate novel culturally appropriate interventions to treat depression and improve diabetes self-management in this population.

Although community-based diabetes education programs are available to almost all older African Americans, those who are depressed or have fewer years of education may not seek them out, and physicians and nurse educators may fail to appreciate the fatalistic attitudes and altered risk perceptions that depression and low health literacy engender.32 For medical providers and diabetes educators, greater awareness of the effects of depression will encourage them to screen for depression in all patients with diabetes, help patients attain more realistic appraisals of their health, and support efforts to improve glycemic control when depression is present.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement (CURE) Program (SAP#4100051727). The department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

References

- 1.Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, Bertoni AG, Schreiner PJ, Diez Roux AV, Lee HB, Lyketsos C: Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA 299:2751–2759, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan A, Lucas M, Sun Q, van Dam RM, Franco OH, Manson JE, Willett WC, Ascherio A, Hu FB: Bidirectional association between depression and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. Arch Intern Med 170:1884–1891, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carnethon MR, Kinder LS, Fair JM, Stafford RS, Fortmann SP: Symptoms of depression as a risk factor for incident diabetes: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971–1992. Am J Epidemiol 158:416–423, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rustad JK, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB: The relationship of depression and diabetes: pathophysiological and treatment implications. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36:1276–1286, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egede LE, Grubaugh AL, Ellis C: The effect of major depression on preventive care and quality of life among adults with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 32:563–569, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ: Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 63:619–630, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyoo IK, Yoon S, Jacobson AM, Hwang J, Musen G, Kim JE, Simonson DC, Bae S, Bolo N, Kim DJ, Weinger K, Lee JH, Ryan CM, Renshaw PF: Prefrontal cortical deficits in type 1 diabetes mellitus: brain correlates of comorbid depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69:1267–1276, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner JA, Abbott GL, Heapy A, Yong L: Depressive symptoms and diabetes control in African Americans. J Immigr Minor Health 11:66–70, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirk JK, D’agostino RB, Bell RA, Passmore LV, Bonds DE, Karter AJ, Narayan KMV: Disparities in HbA1c levels between African-American and non-Hispanic white adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 29:2130–2136, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, Koeske G, Rosen D, Reynolds CF, Brown C: Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: the impact of stigma and race. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 18:531–543, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miranda J, Cooper LA: Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 19:120–126, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joo JH, Morales KH, de Vries HF, Gallo JJ: Disparity in use of psychotherapy offered in primary care between older African-American and white adults: results from a practice-based depression intervention trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:154–160, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborn CY, Trott H, Buchowski MS, Patel KA, Kirby LD, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ, Cohen SS, Schlundt DG: Racial disparities in the treatment of depression in low-income persons with diabetes. Diabetes Care 33:1050–1054, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasckow J, Ingram E, Brown C, Tew JD, Conner KO, Morse JQ, Haas GL, Reynolds CF, Oslin DW: Differences in treatment attitudes between depressed African-American and Caucasian veterans in primary care. Psychiatr Serv 62:426–429, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases : Diabetes in African Americans. Bethesda, Md., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, 2005 (NIH Publication No. 02–3266) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson A: Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc 94:666–668, 2002 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV: Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA 287:2519–2527, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janz NK, Champion N, Strecher VJ: Health Belief Model. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 3rd ed. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, Eds. San Francisco, Calif, Jossey-Bass, 2002, p. 45–66 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casten R, Brawer R, Haller J, Hark L, Henderer J, Leiby B, Murchison A, Plumb J, Rovner B, Weiss D: A trial of a behavioral intervention to increase dilated fundus exams in African Americans aged 65+ with diabetes. Expert Rev Ophthalmol 6:593–601, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker EA, Caban A, Schechter CB, Basch CE, Blanco E, DeWitt T, Kalten MR, Mera MS, Mojica G: Measuring comparative risk perceptions in an urban minority population: the Risk Perception Survey for Diabetes. Diabetes Educ 33:103–110, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinger K, Butler HA, Welch GW, La Greca AM: Measuring diabetes self-care: a psychometric analysis of the Self-Care Inventory-Revised with adults. Diabetes Care 28:1346–1352, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16:606–613, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL: Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 21:547–552, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gary TL, Crum RM, Cooper-Patrick L, Ford D, Brancati F: Depressive symptoms and metabolic control in African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 3:23–29, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lustman PJ, Clouse RE: Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications 19:113–122, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson LK, Egede LE, Mueller M: Effect of race/ethnicity and persistent recognition of depression on mortality in elderly men with type 2 diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care 31:880–881, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin EHB, Rutter CM, Katon W, Heckbert SR, Ciechanowski P, Oliver MM, Ludman EJ, Young BA, Williams LH, Mcculloch DK, Von Korff M: Depression and advanced complications of diabetes. Diabetes Care 33:264–269, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCleary-Jones V: Health literacy and its association with diabetes knowledge, self-efficacy and disease self-management among African Americans with diabetes mellitus. ABNF J 22:25–32, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewinsohn P: A behavioral approach to depression. In Psychology of Depression: Contemporary Theory and Research. Friedman RJ, Katz MM, Eds. Oxford, England, John Wiley & Sons, 1974, p. 157−185 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akincigil A, Olfson M, Siegel M, Zurlo KA, Walkup J, Crystal S: Racial and ethnic disparities in depression care in community-dwelling elderly in the United States. Am J Public Health 102:319–328, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EH, Rutter C, Manning WG, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young BA: Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:65–72, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egede LE, Bonadonna R: Diabetes self-management in African Americans: an exploration of the role of fatalism. Diabetes Educ 29:105–115, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]