Abstract

This article is a review of the genes and genetic disorders that affect hearing in humans and a few selected mouse models of deafness. Genetics is playing an increasingly critical role in the practice of medicine. This is not only in part to the importance that genetic knowledge has on traditional genetic diseases but also in part to the fact that genetic knowledge provides an understanding of the fundamental biological process of most diseases. The proteins coded by the genes related to hearing loss (HL) are involved in many functions in the ear, such as cochlear fluid homeostasis, ionic channels, stereocilia morphology and function, synaptic transmission, gene regulation, and others. Mouse models play a crucial role in understanding of the pathogenesis associated with these genes. Different types of familial HL have been recognized for years; however, in the last two decades, there has been tremendous progress in the discovery of gene mutations that cause deafness. Most of the cases of genetic deafness recognized today are monogenic disorders that can be broadly classified by the mode of inheritance (i.e., autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, and mitochondrial inheritance) and by the presence of associated phenotypic features (i.e., syndromic; and nonsyndromic). In terms of nonsyndromic HL, the chromosomal locations are currently known for ~ 125 loci (54 for dominant and 71 for recessive deafness), 64 genes have been identified (24 for dominant and 40 for recessive deafness), and there are many more loci for syndromic deafness and X-linked and mitochondrial DNA disorders (http://hereditaryhearingloss.org). Thus, today’s clinician must understand the science of medical genetics as this knowledge can lead to more effective disease diagnosis, counseling, treatment, and prevention.

Keywords: nonsyndromic hearing loss, genetics, gene, mutation, diagnosis, treatment

GENETIC EPIDEMIOLOGY OF DEAFNESS

Hearing loss (HL) affects ~ 70 million people worldwide. About 50%–60% of these cases have a genetic etiology; the remaining 40%–50% of cases are attributed to environmental factors such as ototoxic drugs, prematurity, or trauma (Cohen and Gorlin, 1995; Tekin et al., 2001). However, as public health awareness is improved, environmental factors are contributing less to the etiology or deafness and the relative proportion of genetic HL is increasing (Marazita et al., 1993). Approximately, one in every 1,000 children has some form of prelingual hearing impairment (Morton, 1990), and one in 2,000 is caused by a genetic mutation. About 30% of cases of prelingual deafness are classified as syndromic; the remainder cases are nonsyndromic.

Approximately 80% of genetic deafness is nonsyndromic (not associated with other clinical features), and autosomal recessive forms account for 60%–75% of the cases. Of the remaining cases, 20%–30% show autosomal dominant inheritance and about 2% are either X-linked or of mitochondrial origin (Morton, 1991). Hereditary HLs can range from mild to profound and autosomal recessive, and sex-linked losses tend to be more severe than dominant (Liu and Xu, 1994). Genetic HL can also be progressive and, in human, onset and progression may occur in infancy and childhood. Progressive HL impairs a staggeringly large proportion of human population (Davis et al., 1986).

Genetic deafness is a classic example of multilocus genetic heterogeneity. This extreme heterogeneity of human deafness often hampered genetic studies because many different genetic forms of HL give rise to similar clinical phenotypes, and conversely, mutations in the same gene can result in a variety of clinical phenotypes. Despite the fact that deafness is a highly heterogeneous disorder, major progress has been made in the identification of the specific genes and mutations that contribute to HL, and the molecular approach to the genetic epidemiology of deafness has been successful in unraveling the allelic spectrum of HL, that is, the number and frequency of the individual deafness alleles, which varies enormously from locus to locus as well as from population to population.

Hereditary HL

Although our knowledge of many genetic causes of HL has expanded greatly in recent years, it is important to understand the relative contributions of certain genes in order to apply molecular diagnostics in clinical practice. Cytomegalovirus infection remains the most common environmental cause of congenital HL. However, increasing prevention of environmental and prenatal causes of HL is making the balance shift in favor of genetic etiologies (Liu et al., 1994; Smith et al., 2005).

Syndromic HL is associated with distinctive clinical features and accounts for 30% of hereditary HL, whereas nonsyndromic HL accounts for the other 70%. Of the more than 400 syndromes in which HL is a recognized feature, Usher syndrome, Pendred syndrome (PS), and Jervell and Lange-Nielson syndrome are the most frequent syndromes. Some forms of syndromic HL demonstrate allelic heterogeneity, in which a condition is caused by mutations in one particular gene; however, different patients show multiple sequence variants of that gene. Genetic testing for syndromic HL usually takes a more directed approach based on previously identified clinical features (Smith et al., 2004).

Nonsyndromic HL can be classified into four groups by the inheritance pattern, and relatively common clinical features have been noted for each inheritance pattern with a few exceptional genes, genotypes, and patients. Autosomal recessive inheritance accounts for 80% of congenital nonsyndromic hereditary HL and is usually prelingual, whereas autosomal dominant inheritance accounts for most of the other 20% and is more often postlingual. Autosomal recessive inheritance most frequently results in severe HL, which presents very early. Patients with autosomal dominant inheritance typically show progressive SNHL, which begins at 10–40 years, and the degree of HL is various (Liu et al., 1994).

Patients with mitochondrial inheritance tend to develop progressive SNHL, which begins at 5–50 years, and the degree of HL is various (Liu et al., 2008). X-linked and mitochondrial inheritance account for only 1%–2% of nonsyndromic HL. However, mitochondrial DNA mutations, primarily A155G and A3243G, are often included in genetic screening as their prevalence increases with age. These mutations are found in ~ 6% of adults with SNHL without a known cause.

Common Deafness Genes

Since the first nonsyndromic deafness gene was discovered in 1993, more than 100 loci for deafness genes have been mapped and more than 60 genes have been implicated in nonsyndromic HL (Hereditary Hearing Loss Homepage; http://webh01.ua.ac.be/hhh/). Most of these genes play roles within the cochlea and thus hereditary HL almost exclusively features cochlear dysfunction (Smith et al., 2005; Morton and Nance, 2006; Yan and Liu, 2008). Genetic screening is most applicable to nonsyndromic HL as these conditions very often have an indistinguishable phenotype. Targeted genetic testing focuses on identifying allele variants of genes, which have the greatest contribution to genetic HL. However, the diagnostic yield is also dependent on the patient ethnicity and the prevalence of certain mutations.

For autosomal recessive HL, the most frequent causative genes in order of frequency are GJB2, SLC26A4, MYO15A, OTOF, CDH23, and TMC1. For each of these genes, at least 20 mutations have been reported. Autosomal dominant common mutations include WFS1, MYO7A, and COCH. Several of these genes are also implicated in syndromic HL.

Nonsyndromic loci are being discovered at a very rapid pace. Currently, ~ 125 loci have been discovered: 54 autosomal dominant, 71 autosomal recessive, five X-linked, two modifier, and one Y linked. Many of these loci share a common gene, whereas others have unknown genes. Nonetheless, each type of inheritance has a generalized clinical picture that applies to most of the genes or loci. Autosomal recessive loci tend to produce severe, prelingual deafness at all frequencies; autosomal dominant loci are typically less severe, postlingual, with varying frequencies involved; lastly, X-linked loci affect males more severely than females and can impair all frequencies or only the high frequencies (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Cloned nonsyndromic deafness genes and their phenotypes

| Phenotype |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease (OMIM) |

Locus | Gene (OMIM) |

Chromosome location |

Gene | Protein | Predicted function |

Age of onset | Affected frequency |

Vestibular involvement |

| #124900 | DFNA1 | 602121 | 5q31 | DIAPH1 | Hu homolog of D.

melanogaster Diaphanous gene |

Cytokinesis and cell polarity; regulation of actin polymerization in hair cells of the inner ear |

0–20 | Low to all | |

| #600101 | DFNA2 | 603324 | 1p35.1 | GJB3 | Connexin 31 | Gap junction protein | 20–40 | High | |

| #600101 | DFNA2 | 603537 | 1p34 | KCNQ4 | KCNQ4 | Voltage-gated potassium channel |

10–30 | High | |

| #601544 | DFNA3 | 121011 | 13q11-12 | GJB2 | Connexin 26 | Gap junction protein | 0–20 | High | |

| #601544 | DFNA3 | 604418 | 13q12 | GJB6 | Connexin 30 | Gap junction protein | Mid to high | ||

| #600994 | DFNA5 | 608798 | 7p15 |

ICERE-1/

DFNA5 |

ICERE-1 | Potential role in p53- regulated response to DNA damage in cochlea |

5–15 | High | |

| #600965 | DFNA6/ 14/38 |

606201 | 4p16.1 | WFS1 | Wolframin | Integral, endoglycosidase H-sensitive membrane glycoprotein that localizes primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum |

5–15 | Low | |

| #601543 | DFNA8/12 | 602574 | 11q22-q24 | TECTA | α-Tectorin | Structural component of tectorial membrane |

Variable: prelingual/ postlingual to 9–19 |

Mid (mid to high) |

|

| #601369 | DFNA9 | 603196 | 14q12-q13 | COCH | Cochlin | Extracellular matrix protein |

20–30 | High | Meniere-like symptoms |

| #601316 | DFNA10 | 603550 | 6q23 | EYA4 | EYA4 | Transcriptional activator | 20–60 | All | |

| #601317 | DFNA11 | 276903 | 11q13.5 | MYO7A | Myosin VIIA | Unconventional motor molecule |

All or low | Symptoms of vestibular dysfunction |

|

| #601868 | DFNA13 | 120290 | 6p21.3 | COL11A2 | Collagen 11A2 | Structural molecule | 20–40 | Mid (cookie-bite) | |

| #602459 | DFNA15 | 602460 | 5q31 | POU4F3 | POU4F3 | Transcription factor | 20–40 (with variability to puberty) |

All | |

| #603622 | DFNA17 | 160775 | 22q11.2 | MYH9 | MYH9 | Nonmuscle myosin heavy chain |

5–10 | High | Cochleo-saccular degeneration |

| #606346 | DFNA22 | 600970 | 6q13 | MYO6 | Myosin VI | Unconventional motor molecule |

8–10 | All | |

| #606705 | DFNA36 | 606706 | 9q13-q21 | TMC1 | TMC1 | Transmembrane protein | 0–10 or 30–50 |

High to all | |

| #220290 | DFNB1 | 121011 | 13q11-q12 | GJB2 | Connexin 26 | Gap junction protein | Prelingual | All | |

| #220290 | DFNB1 | 604418 | 13q12 | GJB6 | Connexin 30 | Gap junction protein | Prelingual | All | |

| #600060 | DFNB2 | 276903 | 11q13.5 | MYO7A | Myosin VIIA | Unconventional motor molecule |

Prelingual | All | Symptoms of vestibular dysfunction |

| #600316 | DFNB3 | 602666 | 17p11.2 | MYO15A | Myosin XVA | Unconventional motor molecule |

Prelingual | All | |

| #600791 | DFNB4 (EVA) | 605646 | 7q13 | SLC26A4 | Pendrin | Anion transporter | Prelingual | High to all | Dilated vestibular aqueduct |

| #600974 | DFNB7/11 | 606706 | 9q13-q21 | TMC1 | TMC1 | Transmembrane protein | Prelingual | All | |

| #601072 | DFNB8 | 605511 | 21q22.3 | TMPRSS3 | TMPRSS3 | Serine protease | Prelingual or 10–12 |

All | |

| #601071 | DFNB9 | 603681 | 2p23-p22 | OTOF | Otoferlin | Synaptic vesicle component |

Prelingual | All | |

| #605316 | DFNB10 | 605511 | 21q22.3 | TMPRSS3 | TMPRSS3 | Serine protease | Congenital | ||

| #601386 | DFNB12 | 605516 | 10q21-q22, 3p26-p25 |

CDH23 | Cadherin 23 | Cell adhesion protein | Prelingual | All | |

| #603720 | DFNB16 | 606440 | 15q15 | STRC | Stereocilin | Stereocilia protein | Prelingual or 3–5 |

All | |

| #602092 | DFNB18 | 605242 | 11p15.1 | USH1C | Harmonin | PDZ domain protein | Prelingual | All | |

| #603629 | DFNB21 | 602574 | 11q22-q24 | TECTA | α-Tectorin | Structural component of tectorial membrane |

Prelingual | All | |

| #607039 | DFNB22 | 607038 | 16p12.2 | OTOA | Otoancorin | Anchoring protein between acellular gels and nonsensory cells |

Prelingual | All | |

| 605608 | DFNB29 | 605608 | 21q22.3 | CLDN14 | Claudin 14 | Tight junction protein | Prelingual | All | |

| #607821 | DFNB37 | 600970 | 6q13 | MYO6 | Myosin VI | Unconventional motor molecule |

Prelingual | All | Symptoms of vestibular dysfunction |

| 304500 | DFNX1 | N/A | Xq22 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Variable | All | |

| 304400 | DFNX2 | 300039 | Xq21.1 | POU3F4 | POU3F4 | POU domain transcription factor |

Prelingual | All | |

| 300030 | DFNX3 | 300377(?) | Xp21.2 | DMD (?) | Dystrophin (?) | Membrane structure protein |

Congenital | All | |

| 300066 | DFNX4 | N/A | Xp22 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Postlingual | High to all | |

| 300614 | DFNX5 | N/A | Xq23-27.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Postlingual | Low to all | |

| 40043 | DFNY1 | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7–27 years | All | |

Most gene discoveries are based on a single family where deafness has been inherited. Although nonsyndromic genes only affect hearing, their expression is not necessarily limited to the inner ear. It may be that the inner ear is simply most sensitive to the identified mutation.

GJB2

The most common mutation responsible for nonsyndromic HL is a mutation of the Gap Junction Beta 2 gene (GJB2). It accounts for up to 50% of autosomal recessive HL and thus 20% of all congenital HL (Estivill et al., 1998; Kelley et al., 1998). The GJB2 gene encodes connexin 26, a gap junction protein that allows passage of potassium ions in the inner ear. Immunolabeling results in the mouse show that connexin 26 is expressed by cells in the lateral wall, supporting cells in the organ of Corti and cells in the spiral limbus (Fig. 1A). Enlarged view of the organ of Corti (white box in the Fig. 1A) indicates that connexin 26 is not expressed by hair cells. All supporting cells, however, are extensively connected by gap junctions as revealed by immunolabeling of connexin 26, including the head of Deiters’ cells (small white arrows in Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Cellular expression pattern of connexin 26 in the inner ear of a mouse and the effect of conditional knockout of it on the morphology of the organ of Corti (apical turn). A: Combined differential interference contrast (DIC) imaging and immunolabeling of connexin 26 obtained from a cochlear section. An enlarged view for the area indicated by a white box is given in (B). Scale bar represents ~ 100 μm. B: Immunlabeling of connexin 26 obtained from a section of the organ of Corti. The section is counterstained with DAPI to indicate the location of cell nuclei. Major landmarks of the organ of Corti are labeled. Scale bar represents ~ 100 μm. C: Normal morphology of the organ of Corti (apical turn) of a WT mouse at P14. Runnel of Corti is opened at this stage of development. Scale bar represents ~ 100 μm. D: Typi cal morphology of the apical turn organ of Corti of a conditional connexin 26 knockout mouse. Both inner (big arrowhead) and outer (small arrows) hair cells are intact. The tunnel of Corti remains closed. Scale bar represents ~ 100 μm.

More than 110 different mutations have been identified. The 35delG mutation is the most frequent in the majority of Caucasian populations and may account for 70% of all GJB2 mutations (Snoeckx et al., 2005). The carrier frequency in the mid-western United States is ~ 2.5%, and in this population, roughly two-third of persons with connexin 26 deafness are homozygotes (Green et al., 1999). Other frequent mutations include the 167delT in Ashkenazi Jewish (Morell et al., 1998) and 235delC in Southeast Asians (Ohtsuka et al., 2003; Yan et al., 2003). The closely linked GJB6 codes for connexin 30, and these two genes are often seen in digenic transmission. Combinations of mutations in GJB2 and GJB6 account for about 8% of deaf patients with GJB2 (Pandya et al., 2003).

Mutations in the GJB2 gene produce considerable phenotypic variation, and the degree of deafness can vary from mild to profound. Typically, the audiogram has a down sloping or flat pattern. Symmetry between ears is typical, although one-fourth of individuals have intra-aural differences of up to 20 dB (Cohn and Kelley, 1999; Denoyelle et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2005). The loss tends to be stable, with neither improvement in hearing nor fluctuation in hearing level over the long term. In general, bony abnormalities of the cochlea are not part of the deafness phenotype (less than 10%) and developmental motor milestones and vestibular function are normal (Denoyelle et al., 1999; Green et al., 2003). Several studies have shown that children with GJB2 severe-to-profound HL have excellent outcomes with cochlear implants (Vivero et al., 2010).

It has been shown that from 10% to 42% of patients with GJB2 mutations have only one mutant GJB2 allele (http://www.uia.ac.be/dnalab/hhh/). In our study, 20% of the patients were found to carry single GJB2 mutations (i.e., they are heterozygotes). We assessed clinical characteristics of individuals with nonsyndromic sensorineural HL (NSSNHL) with genetic mutations in GJB2 and/or GJB6 and compared one group with biallelic mutations against a group of heterozygote mutation carriers. We found that these two patient populations have similar incidences in a cohort of patients evaluated for NSSNHL, which is higher than general population heterozygote carrier rates. Heterozygote mutation carriers had less hearing impairment; however, most other factors demonstrated no differences. These results support the theory of an unidentified genetic factor contributing to HL in some heterozygote carriers. Therefore, genetic counseling should consider the complexity of their genetic factors and the limitations of current screening (Lipan et al., 2010).

SLC26A4

Mutations in SLC26A4 are the second most frequent cause of autosomal recessive nonsyndromic HL (ARNSHL), and the resulting phenotypes include PS, an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by sensorineural deafness and goiter (Everett et al., 1997). The deafness is congenital and associated with temporal bone abnormalities that range in severity from isolated enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct [EVA; dilated vestibular aqueduct (DVA)] to Mondini dysplasia, a more complex malformation that also includes cochlear hypoplasia. The thyromegaly in PS is due to multinodular goitrous changes in the thyroid gland, although affected persons typically remain euthyroid. The perchlorate discharge test is often abnormal. In addition to PS, mutations in SLC26A4 cause DFNB4, a type of autosomal recessive HL in which affected persons do not have thyromegaly (Li et al., 1998). No other physical abnormalities cosegregate with DFNB4 deafness, although abnormal inner ear development, and in particular DVA, can be documented by temporal bone imaging. Together, DFNB4 and PS are estimated to account for 1%–8% of congenital deafness. Functional studies suggest that some of the observed phenotypic differences between PS and DFNB4 may be due to the degree of residual function of the encoded protein, pendrin. Mutations that abolish all transport function are more likely to be associated with the PS phenotype, whereas retained minimal transport ability appears to prevent thyroid dysfunction as seen with DFNB4 (Scott and Karniski, 2000).

MYO15A

Mutations in MYO15A cause congenital severe-to-profound HL at the DFNB3 locus. Because MYO15A is encoded by 66 exons, screening for mutations in hearing-impaired individuals is expensive and labor intensive in comparison to a screen for mutations in GJB2 (Cx26), which has only a single protein coding exon. All 28 identified mutations have been found through linkage analysis in consanguineous families, most of which originate in Pakistan. Without the benefit of a prescreen for linkage to DFNB3, it will be a challenge to determine the extent to which mutations of MYO15A contribute to hereditary HL among isolated cases and small families in other populations (Friedman et al., 2002).

OTOF

A mutation of the gene encoding otoferlin (OTOF) is responsible for the DFNB9 subtype of prelingual hearing impairment characterized by auditory neuropathy/auditory dissynchrony (AN/AD). AN/AD is a unique type of HL diagnosed when auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) are absent or severely abnormal; however, outer hair cell (OHC) function is normal as indicated by the presence of otoacoustic emissions (OAEs). These test results indicate that the auditory pathway up to and including the OHC is functioning but that the auditory signal is not transmitted to the brainstem, suggesting that the lesion lies at the level of the inner hair cells (IHCs), that is, the IHCs synapse to the afferent nerve fibers or to the auditory nerve itself. Otoferlin is essential for a late step of synaptic vesicle exocytosis and may act as the major Ca++ sensor triggering membrane fusion at the IHC ribbon synapse (Roux et al., 2006). Individuals with this disorder can have various degrees of HL as measured by pure-tone audiometry. They generally have disproportionately poor speech understanding. In contrast to individuals with non-AN/AD HL, hearing aids may provide little help in speech understanding in most individuals with AN/AD. Cochlear implantation has been shown to help the speech understanding in some cases of AN/AD; however, other cases have not had favorable results (Varga et al., 2006).

The HL can be congenital or late onset, and the hearing level in patients with AN can vary from mild to profound. Speech perception ability is severely impaired and is out of proportion to the pure-tone threshold (Doyle et al., 1998). Audiogram configurations are usually flat; however, a rising audiometric configuration can be seen (28%). HL may be stable (36%) or fluctuating (29%) (Rapin and Gravel, 2003). As evaluations for AN/AD are not routinely performed on every individual with HL, audiogram shapes are sometimes helpful for identifying genetic causes. Patients with OTOF mutations may have better thresholds at high frequencies on pure-tone audiograms or fluctuation in hearing level between tests, as might be expected in AN/AD (Tekin et al., 2005). As spiral ganglion neurons are normal in these patients, cochlear implants have been successful (Rouillon et al., 2006).

CDH23

Usher syndrome is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the gene encoding cadherin-23 (CDH23). Usher syndrome Type 1D (USH1D) is characterized by HL, retinitis pigmentosa, and vestibular dysfunction (Yan and Liu, 2010). The same locus, DFNB12, is the site of a form of nonsyndromic autosomal recessive deafness, which causes moderate-to-profound progressive HL (Schwander et al., 2009). Five of nine Usher genes cause nonsyndromic HL. No single CDH23 mutation predominates as a cause of either USH1D or ARNSHL.

TMC1

TMC1 mutations are one of the more frequent causes of ARNSHL in consanguineous populations. Twenty-one different mutations have been reported in 33 consanguineous families, only one of which was Caucasian. One mutation, c.100C>T seems especially frequent as a cause of ARNSHL and accounts for more than 40% of all TMC1 mutations (Hilgert et al., 2008). TMC1 encodes a transmembrane protein that is required for the normal function of cochlear hair cells. All reported cases show a similar phenotype characterized by prelingual severe-to-profound HL (Hilgert et al., 2009).

WFS1

Wolfram syndrome is a progressive neurodegenerative syndrome characterized by the features “DIDMOAD” (diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness). This autosomal recessive syndrome was first described by Wolfram and Wagner in 1938. Wolfram syndrome is rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 770,000 and a carrier frequency of one in 354. In addition to the four classic features, patients can develop renal tract abnormalities, apnea, cerebellar ataxia, behavioral and psychiatric illness, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and primary gonadal atrophy.

Mutations in WFSl can result in the autosomal recessive Wolfram syndrome or the autosomal dominant form of NSSNHL at the DFNA6/14/38 locus. Wolfram syndrome is characterized by high-frequency SNHL. The HL caused by dominant WFS1 mutations (DFNA6/14/38) is very characteristic, only affecting the low frequencies and rising to normal hearing in the high frequencies (Plantinga, 2008). With age, hearing in the high frequencies is lost and the audioprofile flattens (Hilgert et al., 2009).

MYO7A

It has been shown that a gene encoding an unconventional myosin, myosin VIIA, underlies the mouse recessive deafness mutation, shaker-1, as well as Usher syndrome Type 1b. Mice with shaker-1 demonstrate typical neuroepithelial defects manifested by HL and vestibular dysfunction but no retinal pathology. The MYO7A gene can underlie nonsyndromic deafness (DFNB2) in the human population and that different mutations in the MYO7A gene can result in either syndromic or nonsyndromic forms of HL (Yan and Liu, 2010). This variable manifestation can be explained by allelic heterogeneity or alternatively by the influence of the influence of the genetic background.

Most affected individuals in DFNA11 notice HL in their first decade of life after complete speech acquisition with a subsequent gradual progressive loss. Individuals have bilateral SNHL without vertigo or other associated symptoms. They had symmetric gently sloping or flat audiograms with HL at all frequencies. Individuals between the age of 20 and 60 years generally have moderate HL (Tamagawa et al., 1996).

COCH

Several mutations in the COCH gene have been identified in families with DFNA9, an autosomal dominant progressive SNHL with onset in high frequencies (Robertson et al., 1998). The late onset and the parallel auditory and vestibular decline make this phenotype very recognizable (Hilgert et al., 2009). Onset of HL in patients with DFNA9 occurs between 20 and 30 years, is initially more profound at high frequencies, and displays variable progression to anacusis by 40–50 years. A spectrum of clinical vestibular involvement, ranging from lack of symptoms to presence of vertigo, vestibular hypofunction as assessed by electronystagmography and histopathology, has been found (Robertson et al., 1998).

Mouse Models

The delicate mammalian mechanotransduction apparatus contains multiple interconnected components. The unique endolymphatic environment required for achieving high sensitivity of hearing are not reproducible in any in vitro testing system. These factors create formidable challenges for experimentally testing hypotheses about functional roles of candidate deafness genes. Shortcomings of the in vitro approaches can often be overcome by using animal models to test the causative nature of the gene(s) because mutations identified in human patients could be engineered in mice for developmental, morphological, and functional studies. If the introduced mutation in a given gene specifically leads to hearing defects in the animal model, such a result is a strong indication that the affected genes play a key role in normal hearing function (Friedman et al., 2007). Identification of the key molecules needed in normal hearing greatly facilitates the elucidation of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of the hearing process. These in vivo models are also indispensable for understanding pathogenic process and for testing novel therapeutic methods of treatment.

Before the era of transgenic and gene knockout (KO) mice, mutant mice for studying hereditary deafness are generated by random mutagenesis induced by either physical (e.g., X-ray irradiation) or chemical [e.g., by giving N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea and chlorambucil] methods. Mice carrying mutations spontaneously acquired in research breeding colonies over many years also helped genetic deafness studies in finding new genes involved in HL. Identification of the responsible gene in deaf mice is experimentally more feasible than genetic linkage analysis in large human families. As a result, many deafness genes were identified in hearing-impaired mice prior to their identification in humans (Avraham, 2003).

Increasingly, mouse models functionally null for a particular gene or carrying a dominant negative mutation in a specific gene are produced by targeted gene deletion/modification approach (Friedman et al., 2007). The mouse is currently the only mammalian species in which homologous recombination is feasible for many experimental manipulations to yield a reasonably high chance of success (LePage and Conlon, 2007). Although the mice do not always recapitulate all the human genes and pathways involved in hearing and deafness (Makishima et al., 2005; Parker et al., 2006), it has been proven a powerful tool for studying human deafness. Most available data in understanding pathogenic processes of hereditary deafness are obtained from the mouse models so far. Currently, mutations in more than 180 different genes have been reported as responsible for HL, and many of them have corresponding mouse models (http://hearingimpairment.jax.org/). Examples of the mouse models available for studying genetic deafness are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Examples of mouse models generated for studying human deafness

| Human gene | Human disorder | Mouse gene | Mouse models | Major Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCDH15 | DFNB23 | Pcdh15 | Ames-waltzer | Deafness, circling behavior, head tossing, and hyperactivity |

Alagramam et al., 1999 |

| CDH23 | DFNB12 | Cdh23 | waltzer; waltzer niigata; mdfw;Ahl Albany-waltzer |

NSSNHL with circling behavior, head tossing, and erratic movements |

Di Palma et al., 2001; Wada et al., 2001; Bryda et al., 2001 |

| VLGR1 | USH2C (Usher syndrome Type 2C) |

Vlgr1 | BUB/BnJ and Frings inbred strains; Targeted kO |

Sound-induced seizures and progressive hearing loss |

Skradski et al., 2001; Zheng et al., 1999; Johnson et al., 2005 |

| USH2A | USH2A (Usher syndrome Type 2A) |

Ush2a | Targeted KO | Progressive blindness, moderate and nonprogressive hearing loss at higher frequencies |

Liu et al., 2007; Adato et al., 2005 |

| USH1G/SANs | USH1G (Usher syndrome, Type 1G) |

Ush1g/Sans | Jackson shaker, js | Deafness, hyperactivity, head tossing, and circling behavior |

Weil et al., 2003; Kikkawa et al., 2003 |

| USH1C | USH1C (Usher syndrome Type 1C); DFNB18 |

Ush1c | Deaf circler, dfcr | Deafness, hyperactivity, head tossing, and circling behavior |

Johnson et al., 2003; Verpy et al., 2000 |

| GJB2 | DFNA3A, DFNB1A | Gjb2 | Conditional KO; Cx26R75W | Deafness |

Cohen-Salmon et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2009; Kudo et al., 2003 |

| GJB6 | DFNA3B, DFNB1B | Gjb6 | Targeted KO | Deafness |

Sun et al., 2009; Teubner et al., 2003 |

| CLDN14 | DFNB29 | Cldn14 | Targeted KO | Deafness | Ben-Yosef et al., 2003 |

| KCNE1 | JLNS2 (Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome, locus 2) |

Kcne1 | Targeted KO | Severe hearing loss and vestibular symptoms |

Vetter et al., 1996 |

| KCNQ1 | JLNS1 (Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome, locus 1) |

Kcnq1 | Targeted KO | Severe hearing loss and vestibular symptoms |

Lee et al., 2000; Casimiro et al., 2001 |

| KCNQ4 | DFNA2A | Kcnq4 | Targeted KO; Dominant- negative transgene |

Progressive hearing loss within weeks. No vestibular phenotype |

Kharkovets et al., 2006 |

| SLC26A4 | DFNB4; Pendrin syndrome |

Slc26a4 | Targeted KO | Waltzer-like vestibular dysfunction and complete deafness |

Everett et al., 2001 |

| COL4A3 | Alport syndrome | Col4a3 | Targeted KO | Hearing loss was detected after 6 weeks of age. Homozygotes died at about 14 weeks due to renal failure |

Cosgrove et al., 1998 |

| COL2A1 | STL1 (Stickler syndrome Type I) |

Col2a1 | Disproportionate micromelia, Dmm; Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita, sedc; |

Dwarf, cleft palate, deafness. Died at birth due to lung hypoplasia |

Brown, 1981; Berggren et al., 1997; Donahue et al., 2003 |

| COL11A1 | STL3 (Stickler syndrome Type III) |

Col11a1 | chondrodysplasia, Cho | Cleft palate, severely hearing impaired, died soon after birth due to lethal chondrodysplasia |

Cho et al., 1991 |

| COL11A2 | STL2 (Stickler syndrome Type II); DFNA13, DFNB53 |

Col11a2 | Targeted KO | Shorter long bones, receding snouts, and hearing loss |

McGuirt et al., 1999 |

| COL9A1 | Stickler syndrome | Col9a1 | Targeted KO | Progressive hearing loss | Suzuki et al., 2005 |

| TECTA | DFNA8, DFNA12, DFNB21 | Tecta | Targeted KO; Targeted missense |

Inner ears were less sensitive to sound stimulation |

Legan et al., 2000; Legan et al., 2005 |

| SLC26A5 | DFNB61 | Slc26a5 | Targeted KO | Deafness |

Liberman et al., 2002; Cheatham et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004 |

| MYO7A | DFNB2, DFNA11; USH1B | Myo7a | shaker 1, sh1 | Deafness, hyperactivity, head tossing, and circling behavior |

Gibson et al., 1995 |

| MYO15 | DFNB3 | Myo15 | shaker 2, sh2 | Profound deafness, hyperactivity, head tossing, and circling behavior |

Probst et al., 1998 |

| MYO6 | DFNA22, DFNB37 | Myo6 | snell’s waltzer, sv | Deafness, hyperactivity, head tossing, and circling behavior |

Avraham et al., 1995 |

| SOX2 | Sox2 | Light coat and circling, Lcc; Yellow submarine, Ysb | Complete deafness and circling behavior |

Dong et al., 2002; Kiernan et al., 2005 |

|

| POU4F3/BRN3C | DFNA15 | Pou4f3/Brn3c | Dreidel, ddl; Targeted KO | Profound deafness, hyperactivity, head tossing, and circling behavior |

Erkman et al., 1996; Xiang et al., 1997 |

| NDP | ND: Norrie disease | Ndph | Targeted KO | Blindness, progressive hearing loss beginning at 3 months of age, leading to profound deafness. |

Rehm et al., 2002 |

| ACTG1 | DFNA20, DFNA26 | Actg1 | Targeted KO | Progressive hearing loss | Belyantseva et al., 2009 |

| COCH | DFNA9 | Coch | Targeted missense, late onset hearing loss |

Late-onset, progressive NSSNHL and vestibular dysfunction |

Makishima et al., 2005; Robertson et al., 2008 |

| TMPRSS3 | DFNB10, DFNB8 | Tmprss3 | Targeted KO | Severe deafness and mild vestibular syndrome |

Fasquelle et al., 2011 |

| EYA1 | BOR: branchio-oto-renal syndrome |

Eya1 | Spontaneous—Eya1 bor

Targeted KO |

Complete deafness, circling, head-bobbing behavior, and missing kidneys |

Johnson et al., 1999; Xu et al., 1999 |

| ESPN | DFNB36 | Espn | Jerker, je | Totally deaf from P12d onward, hyperactivity, circling movements, and head tossing |

Zheng et al., 2000b |

| GATA3 | HDR syndrome: hypoparathyroidism, sensorineural deafness, and renal dysplasia |

Gata3 | Targeted KO | Deafness and vestibular dysfunction | Karis et al., 2001 |

| Pax2 | Renal-coloboma syndrome | Pax2 | Targeted KO | Deafness and blindness | Torres et al., 1996 |

TM, tectorial membrane; OHC, outer hair cell; IHC, inner hair cell; SGN, spiral ganglion neuron; NSSNHL, nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss.

After obtaining mouse models, a multidisciplinary approach is usually used to evaluate the effect produced by targeted modification of the candidate genes. Localization of the expression of the candidate gene in the inner ear and finding primary cell types that are affected by the genetic deficiency reveal critical information about functional roles. Protein can be tracked by immunoassays (Di Palma et al., 2001; Hertzano et al., 2007; Qu et al., 2012). The expression of mRNA can be examined by Northern blotting (Di Palma et al., 2001; Friedman et al., 2007). The comparison of temporal and spatial expression patterns of the targeted gene in the inner ear between wild-type (WT) and mutant mice is an effective approach to uncover critical functional and developmental information.

The absence of the stereocilia, hair-bundle defects in growth, orientations, and cohesion, and degeneration of particular types of inner ear cells can be observed by morphological examinations using light microscope, as well as transmission and scanning electron microscopic levels (Skradski et al., 2001; Kiernan et al., 2005; Legan et al., 2005). Paint-fill assay (Morsli et al., 1999) is an effective tool usually used for examining gross development defects. Physiological tests, such as patch clamp recordings made from single cells, are used to measure ion channel/pump activities, membrane potentials, and synaptic activities in hair cells and other types of cells in the inner ear (Nemzou et al., 2006; Ahmad et al., 2007). Motility of OHCs is measured by a combination of voltage-clamp and imaging techniques (Zheng et al., 2000a; Liberman et al., 2002). On the system level, objective measurements of hearing sensitivity can be measured by sound-elicited ABRs from surface-attached electrodes (Ahmad et al., 2007). Functional defects of the vestibular system may be assessed by swimming or other behavioral tests.

Most deafness genes discovered so far are protein-coding genes. These include ion channels, gap junctions, membrane transporters, transcription factors regulating gene expression, adhesion proteins, extracellular matrix proteins, unconventional myosins, and cytoskeletal proteins. In addition, mutations in tRNA- and rRNA-coding genes (Matthijs et al., 1996) and intron region of chromosomes (Wilch et al., 2006) are found to cause deafness. A more complete list of genes can be found at Hereditary Hearing Loss Homepage (http://hereditary-hearingloss.org/). Following are some examples illustrating how the use of animal models has helped the understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of genetic deafness caused by mutation of a particular gene.

Mouse models generated by spontaneous mutations

Spontaneous mutants in a large gene, Cdh23, resulted in multiple lines of mouse models: waltzer (Di Palma et al., 2001); waltzer niigata (Wada et al., 2001); and modifier of deafwaddler-mdfw (Bryda et al., 2001). Homozygote mutant mice display common phenotypes of circling behavior, head tossing, and congenital HL. Heterozygote mutant mice develop late-onset and progressive HL. The heterozygotes also show a higher sensitivity and susceptibility to noise-induced HL (Holme and Steel, 2002). Another mutant, Ahl (Noben-Trauth et al., 2003), show only age-related HL in homozygotes. These mutant mouse strains have helped in revealing the mechanisms of hair cell transduction and age-related deafness.

Examples of mouse models generated by targeted KO

Targeted KO of specific gene can yield remarkable insights about the protein function. In the mouse model of DFNA8 (Legan et al., 2000), null expression of α-tectorin protein (a component of the tectorial membrane) results in the absence of the tectorial membranes, whereas the gross structure of the cochlea and the morphology of the organ of Corti are intact. This specific alteration of one component of the cochlea enabled the study of the interaction between the tectorial membrane and the hair cell bundles. Results showed that the tectorial membrane is required for hair cells to effectively respond to basilar membrane motion. It is critically needed for the mechanism of cochlear amplification that boosted the hearing sensitivity by 35 dB.

In studying the molecular mechanisms of DFNB29, Cldn14-null mutant mice were generated (Wilcox et al., 2001). The Claudin 14 protein was immunolocalized at tight junctions sealing the somas of the hair cells off from the environment of the scal media. Surprisingly, the lack of the tight junction protein neither affected the endocochlear potential (EP) nor the discernible vestibular phenotypes observed. The HL was found to be caused by rapid degeneration of cochlear OHCs, and then followed by the loss of IHCs.

Mouse models helped identifying many of the potassium channels involved in the generation of the EP. Kcne1, Kcnq1, and Kcnq4 encode subunits of inward rectifier voltage-activated potassium channels (Lee et al., 2000; Casimiro et al., 2001). These channels are expressed in the marginal cells of the stria vascularis of the cochlea and in the dark cells of the vestibular system. They open during depolarization and are crucial for the secretion of K+ ions and the generation of the EP. SLC26 (solute carrier protein 26) family of anion exchangers are membrane proteins with about 12 transmembrane domains. Human SLC26A4 (coding for pendrin) mutations is a common autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by congenital deafness and goiter. The expression of pendrin in the cochlea was found to be mostly in apical membranes of the spiral prominence cells and spindle-shaped cells of the stria vascularis (Wangemann et al., 2004). Endolymphatic space in the Slc26a4−/− mouse inner ear is enlarged. However, measurements of endolymphatic potassium (K+) concentration gave normal concentration. Many components needed for K+ secretion and EP generation, including the potassium channels Kcnq1 and Kcne1, Na+/2Cl−/K+ cotransporter Slc12a2, and the gap junction Gjb2, are expressed in the Slc26a4−/− mice. However, Slc26a4−/− mice lack an EP. The results obtained from the Slc26a4−/− mice indicated that the reason for EP loss is caused by a reduced expression of the Kcnj10 protein in the intermediate cells where the EP is initially generated. The loss of Kcnj10 protein expression was suggested to be the direct cause of the loss of the EP and deafness in PS (Wangemann et al., 2004).

Recent studies from a conditional Gjb2 KO in a mouse have made great progress toward elucidating the molecular mechanism of the most common form of human hereditary deafness. Homozygous deletion of Gjb2 is embryonically lethal due to the defect in glucose transport in the placenta (Gabriel et al., 1998). Therefore, conditional Gjb2 KO mice, in which the gene is deleted in either a spatially specific or time-specific manner, were generated by multiple groups (Cohen-Salmon et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2009). Earlier study (Cohen-Salmon et al., 2002) achieved targeted deletion of the Gjb2 using the cre-loxP system by crossing the Gjb2-loxP mouse to Otog-Cre mice carrying the Cre under the Otog promoter that directs the expression of the Cre recombinase specifically in cochlear epithelial cells (Cohen-Salmon et al., 2002). Homozygous mutant mice show hearing impairment, but no vestibular dysfunction. The inner ear seemed to develop normally in the mutant mice. Cell death appeared soon after the onset of hearing, initially affecting only the supporting cells and IHCs.

Wang et al. (2009) generated three independent lines of conditional Cx26 null mice. In all three lines of conditional Cx26 KO mice, they found that the gross cochlear morphology at birth was not distinguishable from the WT. However, postnatal development of the organ of Corti is stalled, as the tunnel of Corti and the Nuel’s space that normally open up around postnatal day (P) 9 in mice (Fig. 1C) are not opened in the organ of Corti of the KO mice (Fig. 1D). This abnormality in the opening of the tunnel of Corti is also observed in the Cx26R75W point mutant mice (Inoshita et al., 2008). Cell degeneration was first observed in the Claudius cells around P8, following by OHC loss at around P13 at middle turn when IHCs are still intact. Massive cell death occurred in the middle turn and basal turns after the onset of hearing, resulting in secondary degeneration of spiral ganglion neurons in the corresponding cochlear locations. Wang et al. (2009) suggested that Cx26 plays essential roles in postnatal maturation of the cochlear morphology and homoeostasis of the organ of Corti before the onset of hearing. As this functional requirement happens before the high K+ concentration and EP are established in the cochlea, these new data indicate that the major function of Cx26 is not involved in the K+ recycling.

The comparison of pathogenesis patterns in conditional Cx26 and Cx30 null mice suggested that mutations of the two Cxs result in deafness by radically different mechanisms. In the cochlea of Cx30 null mice, survival of most IHCs, supporting cells, and SG neurons is observed for up to 18 months. The most severe degeneration is in apical SG neurons and OHCs. OHC loss follows a slow time course and a base to apex gradient. Gross structures of the tunnel of Corti, endolymphatic space, and stria vascularis observed at the light microscope level are unchanged. In contrast, cellular degeneration in the cochlea of conditional Cx26 null mice is dramatically more rapid and widespread than that observed in Cx30 null mice. Homomeric GJs consisting of Cx26 is sufficient for normal hearing (Ahmad et al., 2007). In contrast, homomeric Cx30 GJs overexpressed in the cochlea are not able to sustain normal cochlear development. The dominant functional role in the cochlea played by Cx26 is found to be partially due to its early developmental expression ahead of the Cx30 in the cochlear supporting cells (Qu et al., in press).

How to preserve the integrity of the mammalian mechanotransduction apparatus while experimentally testing each component in it has been an insurmountable task for auditory physiologists for many years. The use of hair cells isolated from the strain of double KO (Tmc1−/−;Tmc2−/−) mice generated by Kawashima et al. (2011) seems to provide a nearly perfect system in which the mechanotransduction channels may be the only missing piece in this complicated device. GFP-tagged Tmc proteins pinpoint its location to the tips of stereocilia at the apical surface of the hair cells, which is where mechanotransduction channels should be localized. Tmc1 and Tmc2 are sufficient for mechanotransduction individually. The expression of the Tmc2 persisted in the vestibular hair cells into adult life. In the early postnatal cochlear hair cells when electrophysiological assessments are feasible, both Tmc1 and Tmc2 are expressed. Only after P8, the Tmc2 expression in hair cells starts to be reduced markedly. Using the Tmc1−/−;Tmc2−/− double KO mice and a viral-mediated rescue approach, Kawashima et al. (2011) found that Tmc1 and Tmc2 encode functionally redundant stereocilia components that are necessary for hair cell mechanotransduction.

Dominant negative point mutant has also been used to produce transgenic mice. Point mutagenesis has been used to generate the Cx26R75W mutant mice (Inoshita et al., 2008). Most Cx26 mutations are loss-of-function mutants. Recently, a gain-of-function Gjb2 mutant, Cx26G45E, known to cause keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KIDS) in humans, was produced by generating an inducible transgenic mouse expressing Cx26G45E specifically in keratinocytes (Mese et al., 2011). The abnormalities found in the mouse model recapitulated the KIDS pathology observed in humans. This novel mouse model enabled the authors to find the increased hemichannel currents in transgenic keratinocytes and revealed the molecular mechanism for disease caused by the G45E mutation.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

The clinical evaluation of the patient with HL is a multidisciplinary endeavor that includes participation by the otolaryngologist, audiologist, clinical geneticist, and other specialists. The etiologic diagnosis is established by a combination of medical history (inclusive of the family history), physical examination, ancillary tests, and DNA testing. Hereditary HL must be differentiated from acquired HL. Hereditary deafness has long been known to account for at least half of childhood SNHL. Among school children, one child in 650–2,000 has some form of hereditary deafness. Common etiologies of acquired deafness include but are not limited to prematurity, hyperbilirubinemia, low birth weight, congenital cytomegalovirus, and meningitis.

Medical History and Physical Examination

The application of a standard protocol to the evaluation of all hearing-impaired persons is not recommended. Historical information and clinical tests should be tailored to specific age groups and types of HL. Historical information should include a detailed gestational, perinatal, and family history. The family history should explore not only HL but also other family traits such as night blindness, premature graying of hair, fainting spells, kidney abnormalities, goiter, dysmorphic features, and parental consanguinity. Careful evaluation for additional clinical manifestations of both hearing-impaired and normal-hearing family members facilitates the diagnosis of most syndromic forms. The examination is supplemented with specific laboratory tests and radiographs based on the clinical assessment. Syndromic deafness accounts for nearly 30% of childhood HL. In contrast, the most common cause of deafness in children is autosomal recessive and nonsyndromic, and the lack of a family history and associated phenotypic features make the diagnosis of genetic deafness more challenging.

Nonsyndromic HL is classified by mode of inheritance; roughly 28% is autosomal dominant (DFNA), 68% autosomal recessive (DFNB), and 4% others (X-linked or DFN, mitochondrial inheritance). In general terms, autosomal recessive deafness is congenital or early-in-onset (i.e., before 2 years of age), and autosomal dominant HL is late-in-onset and progressive. Clinical information alone is typically insufficient to reach an etiologic diagnosis. Nonsyndromic hereditary HL is also genetically heterogeneous with more than 120 genes predicted to cause a similar phenotype. In addition, genetic diseases usually show variable expressivity beyond simple Mendelian inheritance. An affected individual may exhibit few, some, or all of the manifestations of an allele. Occasionally, an individual with a particular gene abnormality will not exhibit the disease phenotype at all, even though he or she can transmit the disease gene to the next generation, and the gene is said to have reduced penetrance. Variable expression of a genetic disease may be caused by genetic or environmental factors. Among the genetic factors, modifier genes, allelic heterogeneity, and genomic imprinting are common. Other genes can influence the expression of a disease-causing gene and are termed modifier genes. For example, Usher syndrome is characterized by HL and blindness, with varying vestibular dysfunction and high genetic heterogeneity. Currently, up to nine genes have been found to cause the various Usher syndrome subtypes. One modifier gene, that is, the gene PDZD7, when mutated in conjunction with another Usher syndrome gene, has been shown to cause both a more severe phenotype and an accelerated onset of retinitis pigmentosa (Ebermann et al., 2010). Allelic heterogeneity refers to the effect that different types of mutations within the same gene (i.e., different alleles) can have on the phenotypic expression. An example of allelic heterogeneity is SNHL due to MYO7A gene defects: separate mutations in this gene are responsible for autosomal recessive nonsyndromic congenital deafness, autosomal dominant nonsyndromic progressive deafness, and syndromic deafness with blindness (Usher syndrome Type 1B). Genetic imprinting is another form of phenotypic variation. An imprintable allele will be transmitted in a Mendelian mode; however, the expression will be determined by the sex of the transmitting parent. Paternal imprinting is used to imply that there will be no phenotypic expression if the disease allele is transmitted from the father; however, his offspring will be nonmanifesting carriers. Other sources of modification of the effect of a gene are alternative splicing, uniparental disomy (both members of an allele pair derive from one parent), and “epigenetic” phenomena such as methylation and histone modification. Additionally, the expression of a gene may depend on an environmental factor, for example, susceptibility to aminoglycoside ototoxicity due to the mitochondrial A1555G DNA mutation (Mendelian inheritance in man; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/).

The basic classification of deafness has become subtly altered by new genetic information. Traditionally, syndromic and nonsyndromic forms have been separated on the basis of associated clinical features. Now it is clear that in some cases, the identical gene can cause both a syndromic and nonsyndromic form of HL (e.g., PS and DFNB4). Another major branch point in the classic classification of deafness has been by etiology, either “genetic” or “acquired” causes. Now it is also clear that in some cases, both a genetic abnormality and an environmental factor may be combined to cause deafness (e.g., mitochondrial DNA mutations and increased risk of aminoglycoside ototoxicity).

Ancillary Tests

Audiologic evaluation

The identification of the HL is done by audiology tests that help to determine the degree of dysfunction and the type of HL. Audiologic tests are age specific. Hearing in newborns is assessed with a combination of OAEs and ABRs tests. Visual-reinforced audiometry and behavioral audiometry are used for younger children, and older children and adults undergo pure-tone and speech audiometry. The basic audiogram entails measuring the auditory threshold for pure tones between 125 and 8,000 Hz. Two separate stimulation strategies are performed, air-conducted (through an earphone) or bone-conducted (through a vibrator on the mastoid process of the skull) stimuli. Air-conducted and bone-conduction threshold curves permit the distinction between the three types of HL: conductive (dysfunction of the eternal or middle ear components), sensorineural (dysfunction of the cochlea or auditory nerve), and mixed involving both conductive and sensorineural. The audiometry is often combined with otoscopy, OAEs, ABR and imaging studies of the ear and auditory nerve to determine the site of dysfunction (external ear, middle ear, cochlea, or auditory neural pathways). The degree of HL is then calculated from the air-conduction thresholds and classified as mild, moderate, severe, or profound HL. Further refinements of the hearing phenotype can be done, such as determining if the HL is (1) bilateral–symmetrical, bilateral–asymmetrical, or unilateral; (2) stable or progressive; and (3) associated with vestibular dysfunction (by history or clinical evaluation of the vestibular system).

Typical pure-tone audiogram profiles (audioprofiles) have been defined in an attempt to define phenotype associated with certain gene mutations, with the purpose of aiding the etiologic diagnosis and guidance for genotyping efforts (Huygen et al., 2007). The audiogram threshold curve is classified into four or five useful audioprofiles: flat, downsloping (i.e., descending curve and high frequency), mid-frequency “U” shaped, and upsloping (i.e., low-frequency HL). In addition, the downsloping audiogram can be further classified into gently sloping and steeply sloping. However, establishing clear phenotype–genotype correlations with audiometric information alone have proven difficult; consequently, additional classificatory data such as progression, severity, and age of onset should be included. Table 1 shows audioprofiles and associated genotypes.

Imaging studies: Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the ear and auditory neural pathways

Imaging studies are commonly obtained during the evaluation of individuals with HL. In addition to facilitating the phenotypic profiling, the identification of cochleo-vestibular dysplasia, absent cochlear nerve, neurofibromas, or associated central nervous system findings has management and prognostic implications. Children with congenital microtia and aural atresia usually have associated middle ear abnormalities and occasionally inner ear abnormalities. Morphological abnormalities of the bony labyrinth are identified in ~ 30% of children and 6% of adults with SNHL (Purcell et al., 2003). Morphogenetic SNHL can be either sporadic or hereditary, and syndromic (Pendred, Brachio-Oto-Renal) or nonsyndromic (DFNB4). The degree of cochlear or vestibular dysplasia is variable and ranges from subtle changes that can only be identified by systematic measurements, such as a mild dysplasia of the lateral semicircular canal, to a total absence of a cochlea and vestibule (Michel aplasia).

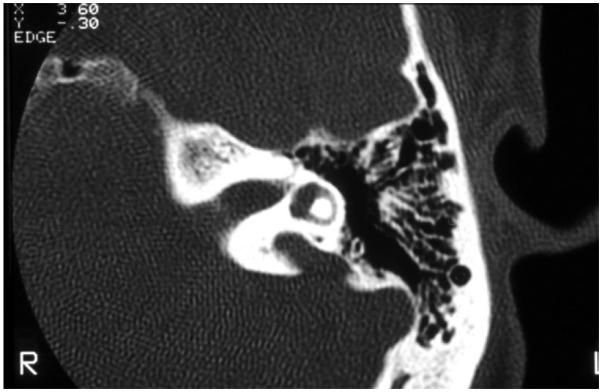

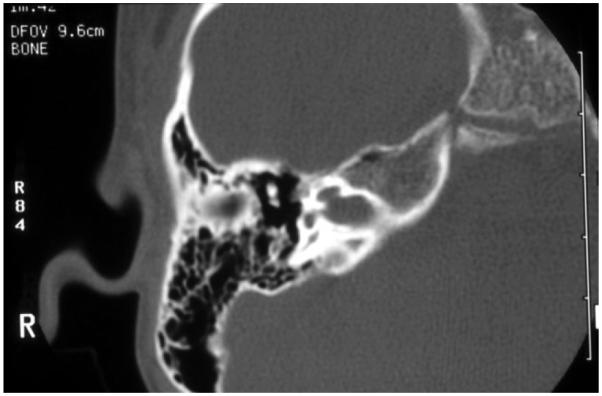

EVA (Figure 2) is one of the most common inner ear malformations associated with SNHL in children. EVA can present in isolation or accompanied by additional cochlear anomalies such as in the “Mondini” triad (i.e., reduced number of cochlear turns with an incomplete osseous partition of the turns, enlarged vestibule, and EVA). A more commonly observed anomaly in EVA ears is a hypoplastic cochlear modiolus (Lemmerling et al., 1997). EVA can accompany malformations in other organs such as in Waardenburg syndrome, Brachio-Oto-Renal syndrome, CHARGE association, and PS. Mutations in the SLC26A4 gene result in PS and are a common cause of EVA (Everett et al., 1997). Mutations in SLC26A4 can also be detected in some patients with nonsyndromic EVA (Usami et al., 1999). In North American Caucasian patients with EVA, biallelic mutations in SLC26A4 are detected in 25%, in another 25% there is only one detectable mutant allele, and in 50% of these patients, there are no mutations (Campbell et al., 2001; Choi et al., 2009). The HL in EVA can vary from congenital to late-in-onset, bilateral to unilateral, progressive or relatively stable, spontaneous or triggered by minor head trauma, and typically the degree of the anatomic abnormality is not directly associated with the degree of HL. An opportunity to prevent or retard the progression of the HL exists in cases with delayed onset. Evidence from Slc26a4 KO mouse studies suggest that the anatomic malformation is not the direct cause of HL in these patients, but rather is a radiologic marker for some underlying genetic defect. These studies demonstrate that acidification and enlargement of the scala media are early events in the pathogenesis of deafness. The enlargement is driven by fluid secretion in the vestibular labyrinth and a failure of fluid absorption in the embryonic endolymphatic sac (Griffith and Wangemann, 2011). Another distinguishable cochlear malformation is the one encountered in X-linked mixed HL with stapes gusher (the latter in cases undergoing stapes surgery to correct the conductive HL). Computed tomography (CT) shows a patent cochlear canal at the fundus of the internal auditory canal resulting in an abnormal communication between the subarachnoid space and the cochlear fluids (Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

High-resolution computed tomography of the temporal bone, with axial cuts of the left ear, showing an enlarged vestibular aqueduct.

Fig. 3.

High-resolution computed tomography of the temporal bone, with axial cuts of the right ear at the level of the modiolus, of a boy with mixed hearing loss: the cochlear canal is enlarged creating abnormal patency between the cochlear fluids and the subarachnoid space. This child has X-linked mixed hearing loss DFN4.

MRI is used to evaluate patients with AN or severe malformation of the internal auditory canal observed by CT in order to determine the integrity of the auditory nerve. The phenotype in childhood AN is fairly stable and consists of severe congenital deafness. Audiometry and ABR testing confirm the hearing dysfunction; however, these children may have normal responses of the transiently evoked OAEs, indicating the presence of functioning OHCs. Given that successful cochlear implantation requires the presence of an auditory nerve, MRI can aid in selecting AN due to an absent auditory nerve versus an endocochlear dysfunction (i.e., altered synaptic transmission at the hair cell level). The OTOF gene encodes otoferlin, a membrane-anchored calciumbinding protein that plays a role in the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles at the auditory IHC ribbon synapse. Mutations in the OTOF gene result in inherited AN due to interference of the hair cell-auditory nerve fiber synaptic transmission (DFNB9), and these children usually respond favorably to cochlear implantation (Rodríguez-Ballesteros et al., 2003).

Other Ancillary Tests

Table 2 shows some of the ancillary tests that may be helpful for the characterization of the phenotype of the individual with suspected inherited hearing impairment by age of onset. With the advent of DNA tests for the etiologic diagnosis of hereditary HL, most of the proposed tests have been replaced or used only for the identification of associated organ disorders in suspected syndromic deafness. The clinician is urged to conduct a judicious use of ancillary tests that are costly, invasive, and of low yield in light of new strategies of molecular screening.

DNA testing: Genetic screening and molecular diagnosis of deafness

Genetic screening is defined as the analysis of human DNA in order to detect heritable-related mutations. A genetic test is one to detect a heritable disease. We will primarily refer to DNA tests for SNHL; however, keep in mind that other means to diagnose genetic disease are also available, such as RNA, chromosomes, proteins, and certain metabolites.

The recent availability of DNA tests to diagnose genetic HL has revolutionized the way we approach these cases. In some cases, the DNA test has supplanted other more invasive and less accurate tests. The goal of genetic testing is to establish an etiologic basis for HL in the most efficient manner possible. Based on the results of the clinical evaluation, the following should be considered:

Syndromic forms of HL have a genetic origin, except for congenital rubella, toxoplasmosis, and cytomegalovirus embriopathies. When syndromic HL is suspected, gene-specific testing should be carried out. Available DNA tests for diagnosis of syndromic deafness exist for Waardenburg, Usher, Jervell and Lange-Nielsen, and PS syndromes. For a complete list of syndromes and corresponding DNA tests, see Geneclinics (http://www.geneclinics.org).

Nonsyndromic HL (NSHL) is the most common type of genetic deafness, and among these the most common type of inheritance is autosomal recessive (ARNSHL). A family history is not usually evident in ARNSHL as sporadic cases predominate; however, the HL is usually severe and occurs at birth. Autosomal dominant NSHL tends to occur later in life, is progressive, and usually not severe. It is interesting that in some populations particularly in Europe and mid-western United States, one gene alone accounts for just over half of cases of ARNSHL, that is, the connexin 26 gene (Cx26). Thus, the following are recommendations for genetic screening of NSHL: (1) in neonates with congenital HL and no obvious family history: Cx26 mutation screening by gene sequencing and cytomegalovirus IgM titers; (2) the patient has a family history and other first-degree hearing-impaired relatives: Cx26 mutation screening and gene-specific mutation screening if the pedigree shows autosomal dominant inheritance; (3) the pedigree suggests mitochondrial DNA inheritance (maternal inheritance): testing for the A1555G mutation (associated with aminoglycoside ototoxicity) and the A7445G mutation, after excluding Cx26 mutations; (4) if nonsyndromic deafness is suspected and both parents are deaf, Cx26-related deafness is strongly suspected; because Cx26 deafness is the most common in the United States, the vast majority of marriages between deaf individuals who produce deaf off-spring are between individuals with Cx26-related deafness; and (5) in patients with progressive SNHL, imaging studies are recommended to identify inner ear malformations. If a cochlear dysplasia is found (Mondini deformity, DVA), screening for SLC26A4 mutations for PS/DFNB4 is performed.

After genetic testing, it will be possible to ascribe a genetic etiology to the HL in many persons. For example, a child may be diagnosed with Cx26 deafness if two mutated alleles are found. We then know the cause of the child’s deafness with certainty and can accurately predict the chance of recurrence in a subsequent child. Alternatively, the test may be negative. A negative screening test does not mean that the deafness is not genetic. This distinction is subtle but very important and must be conveyed to parents prior to testing. In patients with a negative family history and a negative test for Cx26, the probability that the deafness is genetic can be given, and this probability is based on the number of hearing siblings and the ethnic group.

The benefits of genetic testing in single-gene diseases when the genetic loci is known are obvious, such as in DFNB1, and include determination of the cause of HL, avoidance of unnecessary and costly tests, determination of the chance of recurrence of deafness in the family, and identification of relatives at risk. Prenatal diagnosis is possible by obtaining fetal DNA through amniocentesis or chorionic villi sampling; however, there are important pitfalls. Often, there are several loci that cause syndromes or diseases and ruling out one or two may be possible, but will not comprehensively rule out the possibility of a trait. Prenatal diagnosis is therefore not available for every disease associated with a known mutant gene. Merely having the mutant gene does not necessarily mean developing the disease. In most known oncogenes, carrying the mutation places an individual at increased risk but does not predict that a neoplasm will actually occur. Therefore, prenatal testing is currently limited for selected conditions where the clinical usefulness of the screening test has been proven, for example, tests with high predictive value in disorders with specific therapeutic interventions to reduce risk in genetically susceptible individuals.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Grant numbers: DC05575, DC012546; Grant sponsor: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD); Grant numbers: 4R33DC010476, 1R41DC009713, RO1 DC006483.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adato A, Michel V, Kikkawa Y, Reiners J, Alagramam KN, Weil D, Yonekawa H, Wolfrum U, El-Amraoui A, Petit C. Interactions in the network of Usher syndrome type 1 proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:347–356. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S, Tang W, Chang Q, Qu Y, Hibshman J, Li Y, Sohl G, Willecke K, Chen P, Lin X. Restoration of connexin26 protein level in the cochlea completely rescues hearing in a mouse model of human connexin30-linked deafness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1337–1341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606855104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagramam KN, Kwon HY, Cacheiro NL, Stubbs L, Wright CG, Erway LC, Woychik RP. A new mouse insertional mutation that causes sensorineural deafness and vestibular defects. Genetics. 1999;152:1691–1699. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham KB. Mouse models for deafness: lessons for the human inner ear and hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2003;24:332–341. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000079840.96472.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham KB, Hasson T, Steel KP, Kingsley DM, Russell LB, Mooseker MS, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. The mouse Snell’s waltzer deafness gene encodes an unconventional myosin required for structural integrity of inner ear hair cells. NatGenet. 1995;11:369–375. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belyantseva IA, Perrin BJ, Sonnemann KJ, Zhu M, Stepanyan R, McGee J, Frolenkov GI, Walsh EJ, Friderici KH, Friedman TB, Ervasti JM. Gamma-actin is required for cytoskeletal maintenance but not development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9703–9708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900221106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yosef T, Belyantseva IA, Saunders TL, Hughes ED, Kawamoto K, Van Itallie CM, Beyer LA, Halsey K, Gardner DJ, Wilcox ER, Rasmussen J, Anderson JM, Dolan DF, Forge A, Raphael Y, Camper SA, Friedman T. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2049–2061. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren D, Frenz D, Galinovic-Schwartz V, Van de Water TR. Fine structure of extracellular matrix and basal laminae in two types of abnormal collagen production: L-proline analog-treated otocyst cultures and disproportionate micromelia (Dmm/Dmm) mutants. Hear Res. 1997;107:125–135. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KS, Cranley RE, Greene R, Kleinman HK, Pennypacker JP. Disproportionate micromelia (Dmm): an incomplete dominant mouse dwarfism with abnormal cartilage matrix. Embryol Exp Morphol. 1981;62:165–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryda EC, Kim HJ, Legare ME, Frankel WN, Noben-Trauth K. High-resolution genetic and physical mapping of modifier-of-deafwaddler (mdfw) and Waltzer (Cdh23v) Genomics. 2001;73:338–342. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Cucci RA, Prasad S, Green GE, Edeal JB, Galer CE, Karniski LP, Sheffield VC, Smith RJ. Pendred syndrome, DFNB4, and PDS/SLC26A4 identification of eight novel mutations and possible genotype-phenotype correlations. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:403–411. doi: 10.1002/humu.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro MC, Knollmann BC, Ebert SN, Vary JC, Jr., Greene AE, Franz MR, Grinberg A, Huang SP, Pfeifer K. Targeted disruption of the Kcnq1 gene produces a mouse model of Jervell and Lange-Nielsen Syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2526–2531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041398998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham MA, Huynh KH, Gao J, Zuo J, Dallos P. Cochlear function in Prestin knockout mice. J Physiol. 2004;560:821–830. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Yamada Y, Yoo TJ. Ultrastructural changes of cochlea in mice with hereditary chondrodysplasia (cho/cho) Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;630:259–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb19598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BY, Stewart AK, Madeo AC, Pryor SP, Lenhard S, Kittles R, Eisenman D, Jeffrey Kim H, Niparko J, Thomsen J, Arnos KS, Nance WE, King KA, Zalewski CK, Brewer CC, Shawker T, Reynolds JC, Butman JA, Karniski LP, Alper SL, Griffith AJ. Hypo-functional SLC26A4 variants associated with nonsyndromic hearing loss and enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct: genotype-phenotype correlation or coincidental polymorphisms? Hum Mutat. 2009;30:599–608. doi: 10.1002/humu.20884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MM, Gorlin RJ. Epidemiology, etiology and genetic patterns. In: Gorlin RJ, Toriello HV, Cohen MMJ, editors. Hereditary hearing loss and its syndromes. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Salmon M, Ott T, Michel V, Hardelin JP, Perfettini I, Eybalin M, Wu T, Marcus DC, Wangemann P, Willecke K, Petit C. Targeted ablation of connexin26 in the inner ear epithelial gap junction network causes hearing impairment and cell death. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00904-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn ES, Kelley PM. Clinical phenotype and mutations in connexin 26 (DFNB1/GJB2), the most common cause of childhood hearing loss. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D, Samuleson G, Meehan DT, Miller C, McGee J, Walsh EJ, Siegel M. Ultrastructural, physiological, and molecular defects in the inner ear of a gene-knockout mouse model for autosomal Alport syndrome. Hear Res. 1998;121:84–98. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Elfenbein J, Schum R, Bentler RA. Effects of mild and moderate hearing impairments on language, educational, and psychosocial behavior of children. J Speech Hear Disord. 1986;51:53–62. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5101.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoyelle F, Marlin S, Weil D, Moatti L, Chauvin P, Garabedian EN, Petit C. Clinical features of the prevalent form of childhood deafness, DFNB1, due to a connexin-26 gene defect: implications for genetic counselling. Lancet. 1999;353:1298–3000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Palma F, Holme RH, Bryda EC, Belyantseva IA, Pellegrino R, Kachar B, Steel KP, Noben-Trauth K. Mutations in Cdh23, encoding a new type of cadherin, cause stereocilia disorganization in waltzer, the mouse model for Usher syndrome type 1D. Nat Genet. 2001;27:103–107. doi: 10.1038/83660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue LR, Chang B, Mohan S, Miyakoshi N, Wergedal JE, Baylink DJ, Hawes NL, Rosen CJ, Ward-Bailey P, Zheng QY, Bronson RT, Johnson KR, Davisson MT. A missense mutation in the mouse Col2a1 gene causes spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita, hearing loss, and retinoschisis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1612–1621. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Leung KK, Pelling AL, Lee PY, Tang AS, Heng HH, Tsui LC, Tease C, Fisher G, Steel KP, Cheah KS. Circling, deafness, and yellow coat displayed by yellow submarine (ysb) and light coat and circling (lcc) mice with mutations on chromosome 3. Genomics. 2002;79:777. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Morais-Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebermann I, Phillips JB, Liebau MC, Koenekoop RK, Schermer B, Lopez I, Schäfer E, Roux AF, Dafinger C, Bernd A, Zrenner E, Claustres M, Blanco B, Nürnberg G, Nürnberg P, Ruland R, Westerfield M, Benzing T, Bolz HJ. PDZD7 is a modifier of retinal disease and a contributor to digenic Usher syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1812–1823. doi: 10.1172/JCI39715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkman L, McEvilly RJ, Luo L, Ryan AK, Hooshmand F, O’Connell SM, Keithley EM, Rapaport DH, Ryan AF, Rosenfeld MG. Role of transcription factors Brn-3.1 and Brn-3.2 in auditory and visual system development. Nature. 1996;381:603–606. doi: 10.1038/381603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estivill X, Fortina P, Surrey S, Rabionet R, Melchionda S, D’Agruma L, Mansfield E, Rappaport E, Govea N, Milà M, Zelante L, Gasparini P. Connexin-26 mutations in sporadic and inherited sensorineural deafness. Lancet. 1998;351:394–398. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett LA, Belyantseva IA, Noben-Trauth K, Cantos R, Chen A, Thakkar SI, Hoogstraten-Miller SL, Kachar B, Wu DK, Green ED. Targeted disruption of mouse Pds provides insight about the inner-ear defects encountered in Pendred syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:153–161. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett LA, Glaser B, Beck JC, Idol JR, Buchs A, Heyman M, Adawi F, Hazani E, Nassir E, Baxevanis AD, Sheffield VC, Green ED. Pendred syndrome is caused by mutations in a putative sulphate transporter gene (PDS) Nat Genet. 1997;17:411–422. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasquelle L, Scott HS, Lenoir M, Wang J, Rebillard G, Gaboyard S, Venteo S, Francois F, Mausset-Bonnefont AL, Antonarakis SE, Neidhart E, Chabbert C, Puel JL, Guipponi M, Delprat B. Tmprss3, a transmembrane serine protease deficient in human DFNB8/10 deafness, is critical for cochlear hair cell survival at the onset of hearing. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17383–17397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LM, Dror AA, Avraham KB. Mouse models to study inner ear development and hereditary hearing loss. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:609–631. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072365lf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman TB, Hinnant JT, Ghosh M, Boger ET, Riazuddin S, Lupski JR, Potocki L, Wilcox ER. DFNB3, spectrum of MYO15A recessive mutant alleles and an emerging genotype–phenotype correlation. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;61:124–130. doi: 10.1159/000066824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel HD, Jung D, Butzler C, Temme A, Traub O, Winterhager E, Willecke K. Transplacental uptake of glucose is decreased in embryonic lethal connexin26-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1453–1461. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson F, Walsh J, Mburu P, Varela A, Brown KA, Antonio M, Beisel KW, Steel KP, Brown SD. A type VII myosin encoded by the mouse deafness gene shaker-1. Nature. 1995;374:62–64. doi: 10.1038/374062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green GE, Mueller RF, Cohn ES, Avraham KB, Kanaan M, Smith RJH. Audiologic manifestations and features of connexin 26 deafness. Audiolog Med. 2003;1:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Green GE, Scott DA, McDonald JM, Woodworth GG, Sheffield VC, Smith RJ. Carrier rates in the midwestern United States for GJB2 mutations causing inherited deafness. JAMA. 1999;281:2211–2216. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.23.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith AJ, Wangemann P. Hearing loss associated with enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct: mechanistic insights from clinical phenotypes, genotypes, and mouse models. Hear Res. 2011;281:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzano R, Dror AA, Montcouquiol M, Ahmed ZM, Ellsworth B, Camper S, Friedman TB, Kelley MW, Avraham KB. Lhx3, a LIM domain transcription factor, is regulated by Pou4f3 in the auditory but not in the vestibular system. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:999–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgert N, Alasti F, Dieltjens N, Pawlik B, Wollnik B, Uyguner O, Delmaghani S, Weil D, Petit C, Danis E, Yang T, Pandelia E, Petersen MB, Goossens D, Favero JD, Sanati MH, Smith RJ, Van Camp G. Mutation analysis of TMC1 identifies four new mutations and suggests an additional deafness gene at loci DFNA36 and DFNB7/11. Clin Genet. 2008;74:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgert N, Smith RJ, Van Camp G. Forty-six genes causing nonsyndromic hearing impairment: which ones should be analyzed in DNA diagnostics? Mutat Res. 2009;681:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]