Abstract

There is currently limited research on the potential mechanisms underlying the development of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). One such mechanism, distress tolerance (defined as an individual’s behavioral persistence in the face of emotional distress) may underlie the development of ASPD and its associated behavioral difficulties. It was hypothesized that substance users with ASPD would evidence significantly lower levels of distress tolerance than substance users without ASPD. To test this relationship, we assessed 127 inner-city males receiving residential substance abuse treatment with two computerized laboratory measures of distress tolerance. The mean age of the sample was 40.1 years (SD = 9.8) and 88.2% were African American. As expected, multiple logistic regression analyses indicated that distress intolerance significantly predicted the presence of an ASPD diagnosis, above and beyond key covariates including substance use frequency and associated Axis I and II psychopathology. Findings suggest that distress tolerance may be a key factor in understanding the development of ASPD, setting the stage for future studies expanding on the nature of this relationship, as well as the development of appropriate interventions for this at-risk group.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fourth Edition, antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is characterized by a pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others in the form of irresponsible, deceitful, impulsive, and aggressive behaviors. Symptoms include engagement in impulsive and chaotic behaviors, as well as an inability to inhibit emotional responses, tolerate frustration and boredom, and problem-solve (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Lifetime prevalence estimates suggest that 3.6% of the population meets criteria for ASPD, with considerably higher rates in men (5.5%) than women (1.9%; Compton, Conway, Stinson, Colliver, & Grant, 2005). ASPD is a significant public health concern, as studies indicate that the presence of this disorder is strongly associated with substance use (Compton et al., 2005), as well as violent behavior including homicide (Eronen, Hakola, & Tiihonen, 1996), child abuse (Dinwiddie & Bucholz, 1993), and intimate partner abuse (Fals-Stewart, Leonard, & Birchler, 2005).

Although much is known about the behavioral correlates and associated negative outcomes of ASPD, less is understood about the development of this disorder. However, research on the development of ASPD has identified childhood aggression as one of the strongest risk factors for antisocial behavior in adolescence and young adulthood (Broidy et al., 2003; Loeber & Hay, 1997). As such, an understanding of the mechanisms underlying aggression may provide insight into potential underlying mechanisms of ASPD. Empirical evidence across multiple studies suggests that aggressive behavior is attributable to the coupling of self-regulation problems with proneness to frustration and anger (Caspi, Moffitt, Newman, & Silva, 1996; Calkins & Fox, 2002; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Rothbart, Ellis, Rueda, & Posner, 2003; Shiner, Masten, & Roberts, 2003). As an extension to these findings, Deckard, Petrill, & Thompson (2007) recently examined the independent and combined genetic liability for aggression and delinquency, with a specific focus on self-regulation and negative affect. Findings indicated that although both affective vulnerability (e.g., anger/frustration) and self regulatory behavior (e.g., task persistence) have independent genetic links with aggression and delinquency, their combined influence confers the greatest risk (Deckard, Petrill, & Thompson, 2007). In other words, negative affect and self regulatory behavior alone do not capture fully one’s likelihood of engaging in aggressive behavior. Instead, one’s ability to regulate negative affect may be the determining factor. As such, investigation into the assessment of this process and its relationship to ASPD may provide a useful starting point in understanding the development of the disorder.

Specifically, one construct of particular relevance is distress tolerance, defined as the ability to persist in goal directed behavior while experiencing emotional distress. The concept of distress tolerance was initially introduced with regard to borderline personality disorder (BPD), where an absence of distress tolerance was thought to underlie the maladaptive and impulsive behaviors common among individuals with BPD (Linehan, 1993). Specifically, theoretical accounts suggest that deficits in distress tolerance lead individuals with BPD to engage in a range of behaviors that function to reduce intense negative affect, such as deliberate self-harm (Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006; Gratz, 2003), substance use (Bornovalova, Lejuez, Daughters, Rosenthal, & Lynch, 2005), and binge/purge behaviors (Deaver, Miltenberger, Smyth, Meidinger, & Crosby, 2003; Fischer, Smith, Anderson, & Flory, 2003). Further, studies have found that both outpatients with BPD (Gratz et al., 2006) and substance users with BPD (Bornovalova, Gratz, Daughters et al., in press) evidence significantly less willingness to tolerate emotional distress. Findings of a relationship between an unwillingness to tolerate emotional distress and BPD are arguably relevant to understanding ASPD, as BPD and ASPD have been described as “mirror image disorders” (Paris, 1997). This notion is supported by their common symptoms, personality dimensions (Widiger, Trull, Clarkin, Sanderson, & Costa, 2002), risk factors (Skodol, 2000; Zanarini, Gunderson, Stoff, Breiling, & Maser, 1997), and neurobiological substrates (Völlm et al., 2004). Both ASPD and BPD are marked by impulsive traits, irritability, and are thought to have common etiologies, differing mostly by gender-specific factors (APA, 1994; Paris, 1997). Specifically, gender differences in socialization, childhood antecedents, hormones, personality traits, and autonomic indicators have all been implicated in differentiating pathways to ASPD and BPD. Also, in women, childhood antisocial symptoms have been found to predict the development of affect-related BPD criteria in adulthood (Goodman, Hull, Clarkin, Yeomans, 1999), further suggesting an etiological link between the two disorders. Given literature suggesting that BPD and ASPD are highly related forms of psychopathology, the construct of distress tolerance may be equally useful in understanding ASPD and the underlying pathogenesis of this disorder.

The potential role of distress tolerance in the development of ASPD and its associated behaviors is consistent with recent literature suggesting that violent and aggressive behaviors may function to avoid or otherwise regulate emotional responses (Bushman, Baumeister, & Phillips, 2001; Gratz, Rosenthal, Tull, Lejuez, & Gunderson, in press; Jakupcak, 2003; Jakupcak, Lisak, & Roemer, 2002). Specifically, research indicates that individuals who believe that aggressive behavior will alleviate their anger and hostility are more likely to engage in aggressive responses following a negative mood induction exercise, compared to individuals who (a) do not believe that aggressive behavior will improve mood, and (b) believe that aggression will lead to increases in negative mood (Bushman et al., 2001). Further, individuals with a history of aggressive behavior are more likely to believe that aggressive behavior will result in a decrease in negative mood. The use of aggressive behaviors to avoid or escape unwanted emotional responses suggests an underlying unwillingness to remain in contact with these emotional responses, and may be indicative of an absence of distress tolerance. Indeed, a recent study found that emotion dysregulation (of which distress intolerance is a central aspect) mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and intimate partner abuse perpetration among men, interpreted by the authors as providing evidence for the emotion regulating/avoidant function of interpersonally aggressive behaviors (Gratz et al., 2003). Given that aggressive behavior is a central feature of ASPD, distress tolerance may likewise play a central role in this disorder and its associated behaviors.

The goal of the current study was to examine if individuals with ASPD evidence lower levels of distress tolerance than those without ASPD. With regard to the most appropriate sample for examining this question, several issues played into our decision. First, the low base rate of ASPD limits the effective use of random community samples. Additionally, community samples would likely include disproportionate levels of substance use among individuals with ASPD, which would serve as a problematic confound given evidence that distress tolerance is negatively related to a variety of substance use variables (Daughters, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Brown, 2005; Quinn, Brandon, & Copeland, 1996). Because substance use is the most frequently co-occurring condition among those with ASPD, examining the predictors of ASPD among a sample of substance users provides a conservative test of the examined relationships, and allows for a built-in control for the influence of substance use on levels of distress tolerance. Further, although the use of a sample of treatment-seeking individuals detracts from the generalizability of the findings, it also enables the verification of abstinence from substances (eliminating the potentially confounding effects of acute intoxication). Thus, the current study utilized a sample of substance dependent men seeking residential substance abuse treatment (n = 127), with the hypothesis that individuals with ASPD would exhibit lower levels of distress tolerance than individuals without ASPD, controlling for key covariates including substance use frequency, and associated Axis I and II psychopathology.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

Participants included 132 men receiving treatment at the Salvation Army Harbor Light residential substance abuse treatment facility located in northeast Washington, DC. Five individuals were found to meet DSM-IV criteria for psychosis and thus were excluded from further analyses. The final sample (n = 127) ranged in age from 18 to 62, with a mean age of 40.1 years (SD = 9.7). With regard to racial/ethnic background, 88.2% of the participants were African American, 5.5% were White, 4.7% were Hispanic/Latino, and 1.6% reported “other.” In terms of highest education level, 6.3% reported finishing 8th grade or less, 24.4% reported finishing some high school, 34.6% reported a high school degree or GED, 25.2% reported some college or technical school, 2.4% reported a college degree, and 7.1% reported having attended some graduate school or obtaining a graduate or professional degree. The majority of the sample reported current unemployment (72.4%) and a household income of less than $20,000 a year (62.6%). In addition, 78.8% (n = 100) of the sample were mandated to treatment by the court system. The specific court mandated mechanism for this sample included the pretrial release to treatment through the District of Columbia Pretrial Services Agency, in which drug offenders who are awaiting trial are granted the option to receive substance abuse treatment as a way to ensure appearance in court, provide community safety, and address an underlying cause of recidivism.

PROCEDURES

Each assessment session was held on either a Tuesday evening or Friday afternoon in a classroom at the Salvation Army Harbor Light facility. Residents at the treatment center were approached and asked if they would be willing to participate in a study examining how substance users handle stressful situations. They were told that the session would last approximately 1 hour and that they would be paid between $5 and $15 depending on their performance on the computer tasks. Each participant was given a more detailed explanation of the procedures and asked to provide written informed consent approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board.

Given issues of reading comprehension, efforts were made to ensure that participants understood all facets of the consent form and the study itself. Next, the participants completed questionnaires assessing demographics and substance use history. While the participants were completing the questionnaires, individuals trained in administering the laboratory challenge tasks took participants one by one into an adjacent room where they completed the distress tolerance tasks (i.e., PASAT-C, MTPT-C). The order of completion of the tasks was counterbalanced across participants. All participants were reminded before the tasks that the better their performance on the tasks, the more money they would earn. For entry into the treatment center (independent of the current study), individuals were required to evidence abstinence from all drug use and to have completed a detoxification program if needed. As a result, acute drug effects likely did not affect the participants’ scores on the testing battery.

In addition to the questionnaires and challenge tasks, interviews were conducted (see measures section for details). Trained interviewers took participants one by one into a private room to complete the interview. Between completion of the challenge tasks and clinical interview, participants returned to the classroom to finish completing the questionnaires. A proctor was in the classroom at all times to provide instruction and answer any questions the participants may have had. Once the participants completed each aspect of the assessment session (i.e., questionnaire packet, challenge tasks, clinical interview), they were told how much money they had earned and then signed a receipt. Any individual who completed at least one of the challenge procedures without quitting received the entire $15. Individuals who failed to persist through either of the challenge procedures received $10. This payment was deposited into their account at Harbor Light, which they received upon discharge from the residential treatment center. The entire assessment session lasted approximately 1 hour.

MEASURES

DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES

Participants provided basic demographic information including age, gender, education level, occupation, and socioeconomic status.

ASSESSMENT OF PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997, 2002) was administered to assess for Axis I and II disorders, including major depression, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder without agoraphobia, social phobia, antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), and borderline personality disorder (BPD). Interviews were conducted by Ph.D. level clinicians and trained graduate research assistants. Individuals with current psychosis were excluded, as this may have affected their responses on the self report measures and performance on the laboratory tasks.

SUBSTANCE USE

Substance Use Questionnaire

Frequency of past year substance use prior to treatment was assessed with a standard substance use questionnaire (e.g., Babor, Del Boca, Litten, & Allen, 1992). Specifically, participants were asked how often they used a particular substance in the past year prior to treatment. Participants answered this question on a 6-point scale including “never,” “one time,” “monthly or less,” “2 to 4 times a month,” “2 to 3 times a week,” and “4 or more times a week.” The substance categories include: (a) cannabis, (b) alcohol, (c) cocaine, (d) MDMA, (e) stimulants, (f) sedatives, (g) opiates, (h) hallucinogens (other than PCP), (i) PCP, (j) inhalants, and (k) nicotine. Polysubstance use was defined as using three or more substance on a weekly basis in the past year. We chose three substances because the DSM-IV-TR requires that an individual use at least three different substances in the same 12-month period to be given the diagnosis of polysubstance dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

LABORATORY DISTRESS TOLERANCE TASKS

Psychological Stressor I: Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task-Computerized (PASAT-C; Lejuez, Kahler, & Brown, 2003)

We used a modified version of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task, the PASAT-C as an index of distress tolerance, which has been used in previous research with substance users (Daughters, Lejuez, Bornovalova et al., 2005; Daughters, Lejuez, Kahler et al., 2005) and patients with borderline personality disorder (Gratz et al., 2006), and has demonstrated an ability to increase participant distress levels. For this task, numbers were sequentially flashed on a computer screen, and participants were asked to add the presented number to the previously presented number before the subsequent number appeared on the screen. As the task was designed to limit the role of mathematical skill in persistence, the presented numbers only ranged from 0 to 20, with no sum greater than 20. Previous studies have required participants to provide answers by using the mouse to click on the correct answer on a number pad displayed on the screen. Due to limited computer proficiency in the current sample participants provided answers verbally, which is in line with the procedures used by Daughters, Lejuez, Bornovalova et al. (2005). Participants were told that their score increased by one point with each correct answer and that incorrect answers or omissions would not affect their total score. The task consisted of three levels with varying latencies between number presentations. Specifically, the first level of the PASAT-C provided a 3-s latency between number presentations (i.e., low difficulty), the second level provided a 2-s latency (i.e., medium difficulty), and the third level provided a 1-s latency (i.e., high difficulty). The first level lasted for 3 min and the second level lasted for 5 min. Following a 2-min resting period, the final level continued for up to 5 min, with the participant having a termination option. Specifically, participants were informed that once the final level had begun they could terminate exposure to the task at any time by informing the experimenter; however, the amount of money they would earn at the end of the session would depend upon their performance on the task. Distress tolerance was indexed as latency in seconds to task termination. Further, as a manipulation check, an assessment of self-reported dysphoria (see below) was administered at the beginning of the task and at the end of the second level of the PASAT-C to determine if the task increased psychological stress. This second administration occurred at the end of second level of the PASAT-C as opposed to the end of the task to prevent confounds associated with termination latency.

Psychological Stressor II: The Computerized Mirror-tracing Persistence Task (MTPT-C)

As a computerized version of the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task (MTPT; Quinn et al., 1996), we used the MTPT-C (Daughters, Lejuez, Bornovalova et al., 2005). Participants were required to trace a red dot along the outline of a star using the computer mouse. Consistent with the original mirror tracing task, the mouse was programmed to move the red dot in the reverse direction. For example, if the participant moved the mouse to the left then the red dot would move to the right and so on. To increase the difficulty level and resultant frustration, if the participant moved the red dot outside of the lines of the star or if the participant stalled for more than 2 seconds, then a loud buzz would sound and the red dot would return to the starting position. Participants were told that they could end the task at any time by pressing any key on the computer, but that how well they did on the task would affect how much money they made. After receiving instructions the participants began the task and worked independently until the five minute maximum, at which time the task was terminated. The participants were not told the maximum duration prior to beginning the task. Psychological distress tolerance was measured as latency in seconds to task termination.

Dysphoria

In line with previous studies using the distress tolerance tasks (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002; Daughters, Lejuez, Bornovalova et al., 2005), we measured dysphoria using a four item scale consisting of self-reported anxiety, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and frustration, with each item independently rated on a 100 point Likert scale and a total score derived by summing the scores on each item. Reliability of this dysphoria scale was acceptable (α = .77). A baseline administration of the scale occurred at the start of the session and an experimental administration occurred after the second level of the PASAT-C. Because the MTPT-C only included a single level, dysphoria could not be assessed without being confounded by termination latency.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVES ACROSS THE ENTIRE SAMPLE

Diagnostic Status

A total of 46 individuals (36.2%) met DSM-IV criteria for ASPD. In addition, 10.2% (n = 13) of the sample met criteria for borderline personality disorder and 29.1% (n = 37) of the sample met criteria for an Axis I disorder, including major depressive disorder (22.8%; n = 29), bipolar disorder (6.3%; n = 8), generalized anxiety disorder (3.1%; n = 4), obsessive compulsive disorder (2.4%; n = 3), panic disorder without agoraphobia (0.8%; n = 1), and social phobia (0.8%; n = 1). An anxiety disorder composite score was created due to the low percentage of each anxiety disorder among the entire sample. Taken together, 5.5% (n = 7) of the sample met criteria for an anxiety disorder.

Substance Use

With regard to substance use disorder diagnoses, 33.1% of the participants met diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence and 90.6% met criteria for dependence on any illicit drug. The majority of the sample met criteria for cocaine dependence (58.3%; n = 74), followed by heroin (33.1%; n = 42), cannabis (24.4%; n = 31), hallucinogen (12.6%; n = 16), sedative (1.6%; n = 2), and stimulant (0.8%; n = 1) dependence. Past year polysubstance use was reported by 25.2% (n = 32) of the sample.

Distress Tolerance

Overall, individuals persisted on the PASAT-C for an average of 206.9s (SD = 114.2) and the MTPT-C for 216.8s (SD = 98.6). Paired t-tests indicated a significant increase in dysphoria at the experimental administration of the PASAT-C, t(127) = −6.97, p < .001, suggesting that the task was indeed distressing. Importantly, though, persistence on both tasks was not correlated significantly with either pre-task (PASAT-C, r = .24; MTPT-C, r = −.01) or post-task (PASAT-C, r = .08; MTPT-C, r = .20) dysphoria (all p’s > .05). Further, distress tolerance did not vary as a function of the time of day (TOD), which was coded in military time to the nearest hour and analyzed continuously (mean TOD for the assessments = 14:54; SD = 2:30). Specifically, there were no significant correlations between TOD and PASAT (r = .07, ns) or MT (r = −.09, ns) duration. Moreover, there were no significant differences in the time of day (TOD) of the assessment sessions for participants with ASPD (M = 14:20, SD = 2:20) versus those without ASPD (M = 13:54, SD = 1:40) (p = .4). As expected, the PASAT-C and MTPT-C were significantly correlated (r = .38, p < .01).

IDENTIFICATION OF COVARIATES

As displayed in Table 1, covariates were identified by comparing ASPD to non-ASPD participants on demographics, legal status, substance use variables, and diagnostic status.

TABLE 1.

Differences Between Participants With and Without ASPD on Potential Covariates

| ASPD (n = 46) | No ASPD (n = 81) | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 39.8 (SD = 9.7) | 40.2 (SD = 9.7) | t(125) = .23, p = .82 |

| Income (% >20K) | 30.4% | 41.3% | χ2(1) = 1.5, p = .23 |

| Ethnicity (% African American) | 82.6% | 91.4% | χ2(1) = 2.6, p = .14 |

| Marital Status (% Single) | 69.6% | 67.9% | χ2(1) = .04, p = .85 |

| Education (% High School Graduate) | 65.2% | 71.6% | χ2(1) = 0.6, p = .45 |

| Legal Status (% Court Mandated) | 73.9% | 81.5% | χ2(1) = 1.0, p = .32 |

| Substance Dependence | |||

| Alcohol | 34.8% | 32.1% | χ2(1) = 1.00, p = .76 |

| Cocaine | 56.5% | 59.3% | χ2(1) = 1.00, p = .76 |

| Heroin | 37.0% | 30.9% | χ2(1) = 0.49, p = .48 |

| Marijuana | 26.1% | 23.5% | χ2(1) = 0.11, p = .74 |

| Hallucinogen | 15.2% | 11.1% | χ2(1) = 0.48, p = .50 |

| Polysubstance Use | 34.8% | 19.8% | χ2(1) = 3.52, p = .06 |

| Axis-I Disorders | |||

| Major Depression | 32.6% | 17.3% | χ2(1) = 3.91, p = .04 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 10.9% | 3.7% | χ2(1) = 2.56, p = .14 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 6.5% | 4.9% | χ2(1) = 0.14, p = .70 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 19.6% | 4.9% | χ2(1) = 6.83, p = .009 |

Demographics

There were no significant differences between ASPD and non-ASPD participants with regard to age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, income, or court mandated status (p’s > .05).

Diagnostic Status

Significantly more of the ASPD (32.6%) than non-ASPD (17.3%) participants met criteria for current major depressive disorder, χ2(1) = 3.91, p = .04. There were no significant differences in rates of bipolar disorder or any anxiety disorder (p’s > .05). Further, ASPD participants (19.6%) were significantly more likely than non-ASPD participants (4.9%) to meet criteria for borderline personality disorder, χ2(1) = 6.83, p < .01.

Substance Use

There were no between group significant differences in alcohol, cocaine, heroin, marijuana, or hallucinogen dependence (p’s > .05). Although not significant, there was a trend for ASPD (34.8%) participants to report significantly more polysubstance use than non-ASPD (19.8%) participants, χ2(1) = 3.52, p = .06.

DISTRESS TOLERANCE AND ASPD

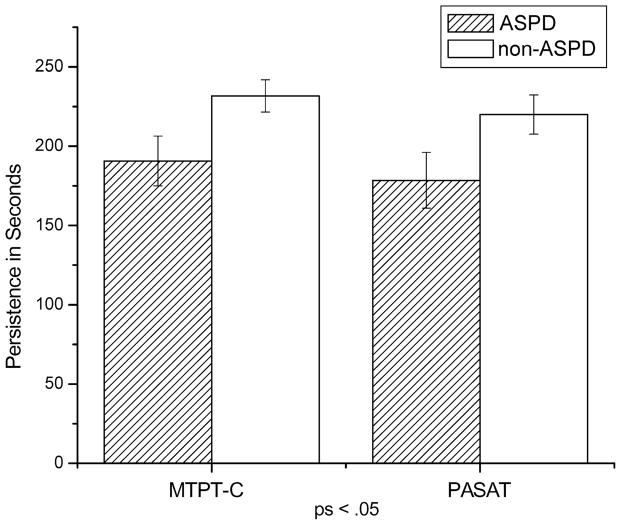

Group differences on the distress tolerance tasks are presented in Figure 1. MTPT-C duration for the ASPD participants (M = 190.7, SD = 106.2) was significantly shorter (i.e., quit the task sooner) than the non-ASPD participants (M = 231.7, SD = 91.5; F = 5.2, p < .05). Likewise, PASAT duration for ASPD participants (M = 178.5, SD = 119.7) was significantly shorter than the non-ASPD participants (M = 220.0, SD = 110.4; F = 3.9, p < .05). Although dysphoria increased from pre- to post-task across the entire sample, post-dysphoria (controlling for pre-task levels), did not differ between ASPD (M = 38.1, SD = 31.3) and non-ASPD (M = 37.3, SD = 27.3) participants, F(1, 126) = .02, p > .05.

FIGURE 1.

Mean differences between ASPD and non-ASPD individuals on the MTPT-C and PASAT. Lower scores indicate less persistence on the tasks (i.e., low distress tolerance). The error bars reflect the standard error of the mean.

Using the significantly associated covariates identified above, we conducted separate logistic regression analyses to examine the unique role of MTPT-C and PASAT in predicting ASPD. Variables that were significantly related to ASPD status (i.e., borderline personality disorder, major depressive disorder, and past year polysubstance use) were entered into the equation first. MTPT-C and PASAT were entered second in separate regressions to determine their unique contribution to ASPD status. As displayed in Table 2, the first step of the model was significant, χ2(3) = 11.56, p < .01, with borderline personality disorder status emerging as a unique predictor of ASPD (Wald = 4.13, p < .05; OR = 1.49; 95% CI = 1.02–2.21). Upon entering MTPT-C in the second step, distress tolerance predicted ASPD status above and beyond the variables in Step 1, χ2(1) = 4.15, p < .05, and the final model remained significant, χ2(4) = 16.6, p < .01. Within the complete MTPT-C model, low distress tolerance (Wald = 5.01, p < .05; OR = 0.64; 95% CI = 0.43–0.95) was a significant predictor of an ASPD diagnosis. Upon entering the PASAT in the second step, distress tolerance predicted ASPD status above and beyond the variables in Step 1, chi;2(1) = 5.11, p < .05, and the final model remained significant, χ2(4) = 15.6, p < .01. Within the complete PASAT model, both borderline personality disorder status (Wald = 4.05, p < .05; OR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.01–2.28) and low distress tolerance (Wald = 4.07, p < .05; OR = 0.67; 95% CI = 0.45–0.99) were significant predictors of an ASPD diagnosis.

TABLE 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting ASPD Status with Covariates of Borderline Personality Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, Past Year Polysubstance Use, and Distress Tolerance. Separate Analyses were Conducted for Each of the Distress Tolerance Tasks (MTPT-C and PASAT). All Variables Were z-Scored to Facilitate Interpretation

| Predictor | B | SE (B) | Wald/χ2 | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1** | χ2(3) = 11.56 | ||||

| Mood Disorder | .29 | .19 | 2.36 | 1.34 | .92–1.95 |

| Past Year Polysubstance Use | .31 | .19 | 2.69 | 1.36 | .94–1.97 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder* | .40 | .19 | 4.13 | 1.49 | 1.02–2.21 |

| Step 2 (MTPT-C)* | χ2(1) = 4.15 | ||||

| Mood Disorder | .30 | .20 | 2.31 | 1.35 | .92–1.99 |

| Past Year Polysubstance Use | .36 | .19 | 3.45 | 1.43 | .98–2.10 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | .35 | .20 | 3.00 | 1.42 | .95–2.12 |

| MTPT-C** | −.44 | .20 | 5.01 | 0.64 | .43– .95 |

| Step 2 (PASAT)* | χ2(1) = 5.11 | ||||

| Mood Disorder | .32 | .20 | 2.53 | 1.37 | .93–2.02 |

| Past Year Polysubstance Use | .27 | .19 | 2.05 | 1.32 | .90–1.92 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder* | .42 | .21 | 4.05 | 1.52 | 1.01–2.28 |

| PASAT* | −.40 | .20 | 4.07 | 0.67 | .45– .99 |

Note. CI = Confidence Intervals

p < .05;

p < .01.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, individuals receiving residential substance use treatment were exposed to laboratory tasks designed to induce heightened levels of emotional distress. It was hypothesized that individuals meeting criteria for antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) would evidence lower levels of distress tolerance than individuals who did not meet criteria for ASPD. As predicted, male substance abusers in residential treatment who met criteria for ASPD exhibited significantly lower levels of distress tolerance on two separate computerized behavioral assessments than their counterparts who did not meet criteria for ASPD. Interestingly, and consistent with other distress tolerance studies (Brown et al., 2002; Daughters, Lejuez, Bornovalova et al., 2005): (a) this group difference in distress tolerance was evident despite a comparable change in dysphoria across the PASAT; and (b) task persistence was not related to pre-task or post-task dysphoria. Thus, although the PASAT was distressing, the measurement of distress tolerance indicates a unique relationship beyond mere group differences in the level of distress induced by the task. These findings indicate that substance users with ASPD are significantly less able to tolerate emotional distress, suggesting an increased vulnerability for engaging in maladaptive behaviors to alleviate emotional distress. In line with reports that violent and/or aggressive behaviors may be attributable to the coupling of self-regulation problems and negative affect (Deckard et al., 2007) and function to escape or avoid unwanted emotional distress (Bushman, Gratz, etc.), these findings set the stage for future research to examine whether distress intolerance is a mechanism underlying some of the symptoms associated with ASPD (e.g., aggression). Similar to substance use and deliberate self harm in BPD, violent and aggressive behavior may function to regulate emotions, serving as a coping mechanism during times of emotional distress.

A few limitations are of note. First, we used a predominantly African-American sample from a residential substance use treatment center. Although this is an underrepresented sample in need of empirical attention, it could be argued that the narrow focus may limit generalizability to other individuals with ASPD. That being said, given that 80% of individuals with ASPD meet lifetime criteria for substance dependence (Kessler, Nelson, McGonagle, Edlund, Frank, & Leaf, 1996), it could be argued that a substance using sample is indeed representative of individuals with ASPD. Further, one advantage of using a substance-using sample is the assurance that individuals from both groups will have experienced at least some consequences of substance use, which may be less evident when using other types of non-ASPD comparison groups. In addition, the combination of ASPD and SUD has been associated with a number of negative individual and societal consequences, including increases in violent and criminal behavior (Swartz & Lurigio, 2004), substance use severity (Cacciola, Alterman, Rutherford, & Snider, 1995; Henderson & Galen, 2003; Mueser et al., 2006), substance use treatment dropout (Martanez-Raga, Marshall, Keaney, Ball, & Strang, 2002), and poor substance use treatment outcomes (Compton, Cottler, Jacobs, Ben-Abdallah, & Spitznagel, 2003). As such, there is a clear need to develop appropriate interventions for this particular patient population. As a second limitation, women were not included in the study design. Although it is important to address ASPD in women, especially given the increase in violent and criminal behavior among this group (Weizmann-Henelius, Viemer, & Eronen, 2004; Warren, Burnette, South, Chauhan, Bale, & Friend, 2002; Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, & Newman, 1997), literature suggesting gender differences in the profiles of ASPD (Skodol, 2000; Goldstein, Powers, McCusker, & Mundt, 1996), including developmental trajectories to the progression of the disorder (van Lier, Vitaro, Wanner, Vuijk, & Crijnen, 2005) suggests the importance of examining the ASPD separately by gender.

Despite limitations, there are several implications from the current research. First, although the clinical relevance of ASPD is high, little is known about the possible mechanisms that underlie the characteristics of this disorder. Further, although treatment outcome research has identified the use of contingency management in treating substance use among individuals with ASPD (Messina, Farabee, & Rawson, 2003), there exist limited treatment protocols specifically designed to treat the maladaptive behaviors associated with ASPD, including aggression, violence, and criminal behavior (Havens & Strathdee, 2005). If further evidence implicates distress tolerance as a mechanism underlying ASPD, appropriate interventions would include those focused on enhancing a patient’s ability to persist through emotional discomfort. Acceptance-based behavioral treatments (e.g., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999; Dialectical Behavior Therapy, DBT; Linehan, Heard, & Armstrong, 1993) may be particularly useful in this regard, as they stem from the view that many maladaptive behaviors are the result of unhealthy attempts to avoid unwanted internal experiences, including emotions (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, & Follette, 1996; Linehan, 1993). Finally, the current results (when combined with previous related work focused on BPD) further implicate distress tolerance as a common mechanism in these two Cluster B personality disorders. Future studies using mixed-gender samples and examining both ASPD and BPD may provide useful information regarding the moderating role of gender in the development of these disorders, with one possibility being that distress tolerance is more relevant for ASPD in men and BPD in women.

The current study provides preliminary evidence that male inner-city substance users with ASPD evidence significantly lower levels of distress tolerance than substance users without ASPD. Further, differences persisted after controlling for theoretically-relevant key variables, including substance use frequency and BPD, all of which have themselves been found to be associated with lower distress tolerance and related mechanisms using similar methodologies (Daughters, Lejuez, Bornovalova et al., 2005; Gratz et al., 2006; Quinn et al., 1996). These findings set the stage for further research examining the specific role of distress tolerance in ASPD using larger, more diverse samples and examining the role of other potentially relevant variables (e.g., the presence of psychopathy). In particular, an examination of the association between distress tolerance and ASPD symptoms such as aggression and violent behavior would further our conceptual understanding of these behaviors and their development.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Del Boca FK, Litten RZ, Allen JP. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ, US: Humana Press; 1992. Just the facts: Enhancing measurement of alcohol consumption using self-report methods; pp. 3–19. Babor Ref. [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Nick B, Delaney-Brumsey A, Lynch TR, et al. The relationship between distress tolerance and borderline personality disorder in two samples of inner city treatment seeking drug users: Preliminary experimental investigation and examination of potential mediators. Psychiatry Research in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Delany-Brumsey A, Paulson A, Lejuez CW. Temperamental and environmental risk factors for borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users in residential treatment. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2006;20:218–231. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2006.20.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Lejuez CW, Daughters SB, Rosenthal MZ, Lynch TR. Impulsivity as a common process across borderline personality and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:790–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, Bates JE, Brame B, Dodge KA, et al. Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:222–245. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF, Phillips CM. Do people aggress to improve their mood? Catharsis beliefs, affect regulation opportunity, and aggressive responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:17–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, Rutherford MJ, Snider EC. Treatment response of antisocial substance abusers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1995;183:166–171. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA. Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: A multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:477–498. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Colliver JD, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and co-morbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:677–685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Cottler LB, Jacobs JL, Ben-Abdallah A, Spitznagel EL. The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:890–895. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Distress tolerance as a predictor of early treatment dropout in a residential substance abuse treatment facility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:729–734. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Psychological distress tolerance and duration of most recent abstinence attempt among residential treatment-seeking substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:208–211. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaver CM, Miltenberger RG, Smyth J, Meidinger A, Crosby R. An evaluation of affect and binge eating. Behavior Modification. 2003;27:578–599. doi: 10.1177/0145445503255571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckard KD, Petrill SA, Thompson LA. Anger/frustration, task persistence, and conduct problems in childhood: A behavioral genetic analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Personality structure: Emergence of the five factor model. Annual Review of Psychology. 1990;50:116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie SH, Bucholz KK. Psychiatric diagnoses of self-reported child abusers. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1993;17:465–476. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(93)90021-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Losoya SH, Valiente C, et al. The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:193–211. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eronen M, Hakola P, Tiihonen J. Factors associated with homicide recidivism in a 13-year sample of homicide offenders in Finland. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47:403–406. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Leonard KE, Birchler GR. The occurrence of male- to-female intimate partner violence on days of men’s drinking: The moderating effects of antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:239–248. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV personality disorders, (SCID-II) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP) [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT, Anderson KG, Flory K. Expectancy influences the operation of personality on behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:108–114. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. Electrodermal hypore-activity and antisocial behavior: Does anxiety mediate the relationship? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;61:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, Powers SI, McCusker J, Mundt KA. Gender differences in manifestations of antisocial personality disorder among residential drug abuse treatment clients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;41:35–45. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman G, Hull JW, Clarkin JF, Yeomans FE. Childhood anti-social behaviors as predictors of psychotic symptoms and DSM-III-R borderline. 1999 doi: 10.1521/pedi.1999.13.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL. Risk factors for and functions of deliberate self-harm: An empirical and conceptual review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Paulson A, Jakupcak M, Tull MT. Exploring the relationship between childhood maltreatment and intimate partner abuse: Gender differences in the mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Violence and Victims. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.68. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Rosenthal MZ, Tull MT, Lejuez CW, Gunderson JG. An experimental investigation of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:850–855. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Strathdee SA. Antisocial personality disorder and opioid treatment outcomes: A review. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2005;4:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson MJ, Galen LW. A classification of substance-dependent men on temperament and severity variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:741–760. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M. Masculine gender role stress and men’s fear of emotions as predictors of self-reported aggression and violence. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:533–541. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Lisak D, Roemer L. The role of masculine ideology and masculine gender role stress in men’s perpetration of relationship violence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2002;3:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Brown RA. A modified computer version of the paced auditory serial addition task (PASAT) as a laboratory-based stressor. The Behavior Therapist. 2003;26:290–293. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE. Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically para-suicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:971–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240055007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Hay D. Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:371–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Newman DL. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: Bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martanez-Raga J, Marshall EJ, Keaney F, Ball D, Strang J. Unplanned versus planned discharges from in-patient alcohol detoxification: Retrospective analysis of 470 first-episode admissions. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2002;37:277–281. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina NP, Farabee D, Rawson R. Treatment responsivity of cocaine-dependent patients with antisocial personality disorder to cognitive-behavioral and contingency management interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:320–329. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Crocker AG, Frisman LB, Drake RE, Covell NH, Essock SM. Conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder in persons with severe psychiatric and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:626–636. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris J. Antisocial and borderline personality disorders: Two separate diagnoses or two aspects of the same psychopathology? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1997;38:237–242. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn EP, Brandon TH, Copeland AL. Is task persistence related to smoking and substance abuse? The application of learned industriousness theory to addictive behaviors. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ellis LK, Rueda MR, Posner MI. Developing mechanisms of temperamental effortful control. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1113–1143. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE. Gender-specific etiologies for antisocial and borderline personality disorders? In: Frank E, editor. Gender and its effects on psychopathology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2000. pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, Masten AS, Roberts JM. Childhood personality foreshadows adult personality and life outcomes two decades later. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1145–1170. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Cognitive empathy and emotional empathy in human behavior and evolution. Psychological Record. 2006;56:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JA, Lurigio AA. Psychiatric diagnosis, substance use and dependence, and arrests among former recipients of supplemental security income for drug abuse and alcoholism. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2004;39:19–38. [Google Scholar]

- van Lier PAC, Vitaro F, Wanner B, Vuijk P, Crijnen AAM. Gender differences in developmental links among antisocial behavior, friends’ antisocial behavior, and peer rejection in childhood: Results from two cultures. Child Development. 2005;76:841–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Völlm B, Richardson P, Stirling J, Elliott R, Dolan M, Chaudhry I, et al. Neurobiological substrates of antisocial and borderline personality disorder: Preliminary results of a functional fMRI study. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health. 2004;14:39–54. doi: 10.1002/cbm.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren JI, Burnette M, South SC, Chauhan P, Bale R, Friend R. Personality disorders and violence among female prison inmates. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2002;30:502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weizmann-Henelius G, Viemer V, Eronen M. Psychological risk markers in violent female behavior. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2004;3:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ, Clarkin JF, Sanderson C, Costa PT. A description of the DSM-III-R and DSM-IV personality disorders with the five-factor model of personality. In: Costa PT, Widiger TA, editors. Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]