Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to quantitatively assess the relationship between therapy-induced changes in left ventricular (LV) remodeling and longer-term outcomes in patients with left ventricular dysfunction (LVD).

Background

Whether therapy-induced changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), end-diastolic volume (EDV), and end-systolic volume (ESV) are predictors of mortality in patients with LVD is not established.

Methods

Searches for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted to identify drug or device therapies for which an effect on mortality in patients with LVD was studied in at least 1 RCT of ≥500 patients (mortality trials). Then, all RCTs involving those therapies were identified in patients with LVD that described changes in LVEF and/or volumes over time (remodeling trials). We examined whether the magnitude of remodeling effects is associated with the odds ratios for death across all therapies or associated with whether the odds ratio for mortality was favorable, neutral, or adverse (i.e., statistically significantly decreased, nonsignificant, or statistically significantly increased odds for mortality, respectively).

Results

Included were 30 mortality trials of 25 drug/device therapies (n = 69,766 patients; median follow-up 17 months) and 88 remodeling trials of the same therapies (n = 19,921 patients; median follow-up 6 months). The odds ratio for death in the mortality trials was correlated with drug/device effects on LVEF (r = −0.51, p < 0.001), EDV (r = 0.44, p = 0.002), and ESV (r = 0.48, p = 0.002). In (ordinal) logistic regressions, the odds for neutral or favorable effects in the mortality RCTs increased with mean increases in LVEF and with mean decreases in EDV and ESV in the remodeling trials.

Conclusions

In patients with LVD, short-term trial-level therapeutic effects of a drug or device on LV remodeling are associated with longer-term trial-level effects on mortality.

While the past 2 decades have seen important advances in therapies for heart failure (HF) (1), there have also been some promising agents—endothelin antagonists (2 and 3), cytokine inhibitors (4), and vasopeptidase inhibitors (5 and 6)—developed through phase 3 clinical testing only to yield negative or neutral results. Because phase 3 trials are by far the most costly and time-consuming phase of drug development, minimization of potential negative or null results is important for the development of new therapies. Thus, it would be very helpful to obtain an early signal of clinical efficacy in the context of shorter, smaller phase 2 trials.

Assessment of ventricular remodeling (i.e., characteristic changes in ventricular volume and wall thickness and shape) is often referred to as a potential surrogate end point for drug or device effects on HF outcomes (1 and 7). Left ventricular end-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV) (8), dimensions (9 and 10), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (11, 12, 13 and 14) are each prognostic when measured at 1 point in time for subsequent mortality risk. Moreover, data from some HF trials of individual therapeutic agents suggest a relation between a drug or device effect on remodeling and the therapeutic effect on natural history outcome (9, 10 and 15). How well therapy-induced changes in these parameters predict therapeutic benefit in mortality outcomes, independent of an individual therapy, has not been quantitatively assessed. Herein, we systematically evaluate the degree to which therapy-induced changes in 3 measures often assessed in remodeling studies (LVEF, EDV, and ESV) are associated with therapeutic effect on mortality outcomes in phase 3 clinical trials in patients with HF and left ventricular dysfunction (LVD).

Methods

General approach

Ideally, the assessment of the relation between the effect of a therapy on remodeling and its effect on mortality would be evaluated in large adequately powered outcome trials, in which all of the patients also had early assessment of remodeling by noninvasive imaging. However, given the expense and complexity of imaging in such a setting, very few trials have included measures of remodeling in all patients, with some exceptions (3, 16, 17, 18 and 19). More often, remodeling is assessed in a substudy population selected from the overall population sample of a trial (20, 21, 22, 23, 24 and 25) or hypotheses are formed based on the results of outcome studies along with smaller remodeling studies from distinct samples of patients (26). We initially identified from the literature drugs or devices for HF patients that were studied in large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating mortality. Then, we systematically identified from the published literature effects of those drugs and devices on remodeling parameters from imaging studies, and examined associations between trial-level (mean) changes in the remodeling outcome and effects on mortality with the same drug or device.

Identification of eligible interventions

We first performed a systematic literature search to identify all drug and device therapies for patients with LVD, for which mortality was evaluated in at least 1 large placebo-controlled RCT with adequate follow-up. For all treatments identified in this set of RCTs (subsequently referred to as “mortality” RCTs), we systematically identified all published placebo-controlled RCTs describing the effects of those treatments on parameters of LV remodeling (subsequently referred to as “remodeling” trials).

Search strategy

We performed several incremental and overlapping MEDLINE searches (covering January 1966 through April 16, 2007) using the keywords “heart failure” and “double-blind” and “placebo.” We first identified qualifying mortality trials that identified the interventions for which a search for remodeling trials was required. The search strategy for the remodeling trials was performed in 2 steps (1966 to 1999 [27] and January 1, 1999, to April 16, 2007). We limited searches to English language peer-reviewed publications on human subjects. Double-blind analysis was a requisite for all studies, except for the device trials.

Thorough examination of citation lists from all retrieved studies, meta-analyses and review articles was conducted to identify additional relevant publications. We complemented searches with input from field experts. Only published studies in peer-reviewed journals were included. Care was taken to include only the most recent or most complete data in the case of overlapping and duplicated data sets. Data from review articles, case reports, abstracts, reports of trial presentations at conferences, and data from letters were not included.

Eligibility criteria

All included trials were English language, double-blind (except device trials), randomized, placebo-controlled trials on human subjects with LVEF ≤45%. For mortality trials, we prospectively required at least 500 patients and at least 6 months of follow-up for eligibility. For remodeling trials, we required the measurement of at least 1 measure of ventricular remodeling (LVEF, volume, or dimension) in active drug and placebo groups over a period of at least 4 weeks, an arbitrary cut-point meant to eliminate very short-term studies of acute effects. There was no minimum sample size for the remodeling trials.

Data extraction

A single investigator (D.G.K.) extracted data on pre-constructed paper forms, receiving input from an experienced methodologist when needed. Information on the publication, the active intervention, and patient characteristics from each trial were extracted. Mean follow-up duration and the number of patients enrolled and analyzed per study arm were recorded.

For each arm in the mortality trials, the number of deaths from all causes was extracted. For the remodeling trials, we recorded information necessary to calculate the mean net difference in LVEF, EDV, ESV, or dimensions over time across the compared randomized arms (28). Typically, this involved recording the means and standard deviations of the pertinent measures before and after treatment.

Calculation of trial-level (mean) effects on mortality and remodeling outcomes

For each intervention, we calculated the odds ratio (OR) for long-term all-cause mortality. When multiple studies existed, we derived summary effects using standard meta-analysis, the Mantel-Haenszel method for 2 studies (29) and the DerSimonian and Laird random effects method for ≥3 studies (30). We tested for heterogeneity with the Q statistic (considered significant for p < 0.10) (31) and calculated its extent with I2 (32). The I2 expresses the proportion of between-study variability that is attributed to heterogeneity rather than chance, with values >50% indicating high heterogeneity (33).

From each remodeling trial, we calculated the mean net difference of the change in the LVEF, EDV, and ESV over time between intervention and placebo groups. As described in the following text under “Correlation and regression analyses,” main analyses considered effects from the remodeling trials separately. To be inclusive of as much extant published data as possible, we prospectively elected to also include data from studies that published results of LV dimensions instead of calculated LV volumes. For remodeling trials that reported only LV dimensions, we transformed mean changes (and variances thereof) in LV dimensions to the corresponding mean changes (and variances) of LV volumes, by using the delta method (34) and the Teicholtz formula (35). Similarly, mean changes (and variances) in LV ESV and EDV indices were transformed to LV volumes using the Mosteller formula for the body surface area (36) and assuming a height of 1.70 m and a weight of 75 kg. The latter are approximates of the median sex-averaged values in the U.S. population aged similarly to the mean ages in our eligible studies (37). Results were not sensitive to small perturbations in these somatometric assumptions (data not shown). We assessed the validity of the transformations in 5 studies reporting 8 pairs of mean changes both in diameters/indices and in volumes. Discrepancies between the estimated (transformed) and actual mean changes were >10 ml in 4 measurements (maximum discrepancy approximately 25 ml in EDV). The transformed values were less extreme than the actual values in 7 of 8 pairs and always smaller than 10 ml. This finding suggests that the transformations bias findings toward the null.

Correlation and regression analyses

For each of the 3 remodeling outcomes (LVEF, EDV, and ESV), main analyses were performed in 3 steps. All main analyses were unadjusted and considered remodeling effects from trials on the same intervention separately. First, we calculated unweighted Spearman correlations between the trial-level remodeling effects and the corresponding summary OR for mortality. These analyses are largely descriptive as they do not account for the statistical errors that accompany the mortality and remodeling effect estimates.

Second, we explored whether there is a simple linear relationship between the log-transformed OR for mortality and the magnitude of the remodeling effects using a general linear model that accounts for heteroskedasticity in the dependent variable (inverse variance weighting) and the clustering of observations by intervention (with robust standard error estimation). This analysis yields the relative OR for mortality per given change in the remodeling parameter.

Third, we examined with logistic and ordinal logistic regressions whether remodeling outcomes can predict whether the OR for mortality was favorable, neutral, or adverse (i.e., statistically significantly decreased, nonsignificant, or statistically significantly increased odds for mortality, respectively) with the corresponding intervention. An intervention was considered to have a favorable mortality effect if the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the OR was <1, a neutral mortality effect if the 95% CI of the OR included 1, and an adverse mortality effect if the lower bound of the 95% CI of the OR was >1. Again, we used inverse variance weighting and accounted for clustering of observations by intervention with robust standard error estimation. This alternative analysis categorizes the effect on mortality into 3 ordinal categories, and informs on the ability of short-term remodeling outcomes to predict effects on mortality in larger trials.

For illustrative purposes, we plotted predicted probabilities for favorable, neutral, or adverse effects on mortality for different magnitudes of remodeling effects, and produced receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is a simple measure of the discriminatory ability of the mean change in the remodeling outcomes to predict mortality. It represents the percentage of all possible discordant pairs of interventions discordant for their mortality effects in which the variable (change in LVEF, EDV, or ESV, respectively) and correctly assigns a higher probability of mortality benefit to the intervention that actually demonstrated benefit. An AUC value of 0.5 implies no discriminatory ability, and an AUC value of 1.0 implies perfect discrimination.

Sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses, regressions were adjusted for the mean value of the remodeling outcome at baseline and for follow-up duration. We also repeated all regression analyses using unweighted regressions, and after eliminating the shorter-term remodeling studies (<12 weeks of follow-up). We performed main analyses excluding studies where we calculated values of changes in ESV and EDV from results on diameters or indices. Finally, additional sensitivity analyses used the meta-analysis-derived summary effect size of all remodeling trials within each drug/device intervention, rather than considering remodeling trials separately (as was done in the main analyses).

All analyses and graphs were performed in Stata SE version 11 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas) and in Meta-Analyst (Tufts Evidence-based Practice Center, 2009). Unless otherwise stated, all p values are 2-tailed and considered significant at the 0.05 level.

Results

Results of search algorithms

The search algorithm yielded 1,992 citations, and 248 articles were retrieved and reviewed in full text. In total, 117 nonoverlapping RCT reports were eligible. We identified 30 large RCTs describing the effects of 25 different interventions on mortality (Fig. 1A) that reported on a total of 69,766 patients over a median follow-up of 17 months. For each individual drug/device intervention for which a mortality trial had been identified, we identified between 1 and 22 remodeling trials. There were 88 remodeling RCTs evaluating 91 distinct drug or device versus placebo comparisons, involving 19,921 patients with median follow-up of 6 months (Fig. 1B). Four of the 30 mortality trials reported serial measurements of remodeling parameters of all patients and, therefore, also qualified as remodeling trials (16, 17, 19 and 38), whereas 11 other remodeling trials were substudies of 1 of the mortality RCTs (20, 21, 22, 25, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 and 45). To assess remodeling, 39 trials employed radionuclide ventriculography, 32 utilized 2-dimensional echocardiography, and 3 utilized magnetic resonance imaging. Fourteen studies used a combination of radionuclide ventriculography and 2-dimensional echocardiography.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Search Pathway for Identification of Mortality Trials. RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial

Figure 1B. Search Pathway for Identification of Remodeling Trials. *86 trials evaluated 89 drug-placebo comparisons (83 parallel arm trials; 3 trials evaluated two drugs versus placebo). RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial

Effect on drug or device therapies on mortality

Table 1 describes the effects of the 25 distinct drug/device therapies on mortality (4, 16, 17, 18, 19, 44, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 and 67). Nine, 12, and 4 interventions had significantly favorable, neutral, and significantly adverse effects on mortality, respectively, in the identified trials. The mortality trials included predominantly male patients (81% on average) with mean ages between 57 and 67 years (median age 63 years). Mean New York Heart Association (NYHA) HF functional class was 2.7 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.7). The median number of patients per individual drug/device intervention was 2,345 (IQR 2,328). The 30 trials followed up patients for a median of 17 months. Two (6%) of the trials evaluated patients with LVD after an acute myocardial infarction; the remaining 29 (94%) trials evaluated patients with chronic HF and LVD.

Table 1.

Drug/Device Effects of Mortality Compared With Placebo in Patients With Heart Failure and LVD

| Intervention (Ref. #) | No. of Studies (n) | OR† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone (17) | 1 (674) | 0.87 (0.64–1.19) |

| Amlodipine (46) | 1 (1,153) | 0.80 (0.63–1.02) |

| Bucindolol (19) | 1 (2,708) | 0.88 (0.75–1.03) |

| Bisoprolol (47) | 1 (2,647) | 0.64 (0.51–0.79) |

| CRT (48) | 2 (1,738) | 0.69 (0.51–0.94) |

| Candesartan (49 and 50) | 2 (4,576) | 0.83 (0.73–0.95) |

| Captopril (51) | 1 (2,231) | 0.79 (0.64–0.96) |

| Carvedilol (52, 53 and 54) | 3 (5,342) | 0.62 (0.47–0.81) |

| Digoxin (55) | 1 (6,800) | 0.99 (0.89–1.09) |

| Enalapril (56) | 1 (2,569) | 0.82 (0.70–0.97) |

| Enalapril-Prev (57) | 1 (4,228) | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) |

| Enoximone (58) | 1 (1,854) | 0.95 (0.76–1.18) |

| Etanercept (4) | 1 (2,356) | 1.22 (0.93–1.61) |

| Felodipine (59) | 1 (450) | 1.07 (0.62–1.84) |

| Flosequinan (60) | 1 (2,345) | 1.42 (1.15–1.76) |

| Hydralazine-ISDN (16 and 61) | 2 (1,509) | 0.70 (0.51–0.96) |

| Ibopamine (62) | 1 (1,906) | 1.27 (1.02–1.57) |

| Metoprolol CR (63) | 1 (3,991) | 0.67 (0.54–0.83) |

| Mibefradil (44) | 1 (2,571) | 1.14 (0.96–1.36) |

| Milrinone (64) | 1 (1,088) | 1.35 (1.03–1.76) |

| Moxonidine (65) | 1 (1,934) | 1.64 (1.05–2.57) |

| Prazosin (16) | 1 (456) | 1.26 (0.87–1.84) |

| Spironolactone (66) | 1 (1,663) | 0.62 (0.51–0.76) |

| Tolvaptan (67) | 1 (4,134) | 0.98 (0.85–1.12) |

| Valsartan (18) | 1 (5,010) | 1.02 (0.89–1.18) |

CI = confidence interval; CR = controlled release; CRT = cardiac resynchronization therapy; ISDN = isosorbide dinitrate; Prev = Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction Prevention trial.

• Enalapril was examined separately when studied in patients with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction (LVD), as this was the only trial which exclusively examined patients with asymptomatic LVD.

When >1 trial existed for a specific therapy, meta-analysis was used to calculate the mortality odds ratio (OR).

Of note, we chose to evaluate the use of enalapril to treat asymptomatic LV dysfunction as a separate entity, as this was the only trial in which all of the patients studied had NYHA functional class I HF (57).

Effect on drug or device therapies on remodeling

We identified 88 remodeling RCTs that included a total of 19,741 patients (median 53 patients per trial; IQR 133) in which the effect of the 25 drug or device therapies (identified from the mortality trials) on remodeling was evaluated. The majority (n = 85 trials) were parallel arm trials, whereas the remaining 3 trials examined 2 separate drugs versus a single placebo arm. The remodeling trials included predominantly male patients (>57% in all trials), with mean ages between 45 and 71 years (median 60 years). Mean NYHA HF functional class was 2.5 (IQR 0.7). Nine (10%) of the trials evaluated patients with LVD after an acute myocardial infarction; the remaining 82 (90%) trials evaluated patients with chronic HF. While the average follow-up was 6 months; 81 trials (89%) had a follow-up of ≥12 weeks.

Mean changes in the LVEF were extracted from 86 trials. Mean changes in EDV and ESV were extracted from only 14 studies; we calculated mean changes in the EDV and ESV from corresponding changes in diameters or indices in 35 of 49 studies and 26 of 40 studies reporting pertinent data, respectively. Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 describe the summary net changes in LVEF, EDV, and ESV for the 25 eligible interventions compared with placebo (16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 49, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138 and 139). For several interventions, between-study heterogeneity was extensive.

Table 2.

Absolute Effect of Drug/Device on Change in EF Compared With Placebo

| Intervention (Ref. #) | No. of Studies (n [Range]) | ΔEF (95% CI)† | Mean Follow-Up Weeks [Range] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone (17, 68 and 69) | 3 (942 [30–674]) | 3.8 (−1.7 to 9.2) | 60.7 [26–104] |

| Amlodipine (70) | 1 (362) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) | 12 |

| Bisoprolol (41) | 1 (28) | 12.0 (4.4 to 19.6) | 52 |

| Bucindolol (19, 71, 72 and 73) | 4 (2,915 [19–2,708]) | 4.2 (3.7 to 4.7) | 22 [12–52] |

| CRT (74, 75, 76 and 77) | 4 (1,052) | 2.7 (1.9 to 3.5) | 21 [6–26] |

| Candesartan (78) | 1 (305) | 4.0 (0.5 to 7.5) | 26 |

| Captopril (79, 80, 81, 82, 83 and 84) | 6 (543 [40–204]) | 3.3 (0.3 to 6.4) | 36.7 [12–52] |

| Carvedilol (23, 24, 49, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102,103 and 104) | 22 (2,780 [15–415]) | 6.9 (5.8 to 8.0) | 30 [13–52] |

| Digoxin (84, 105, 106, 107, 108 and 109) | 6 (624 [13–196]) | 2.7 (1.2 to 4.1) | 48.3 [12–208] |

| Enalapril (20, 42, 110, 111, 112 and 113) | 6 (431 [12–301]) | 3.7 (1.5 to 5.9) | 24 [4–52] |

| Enalapril-Prev (21) | 1 (108) | 2.0 (−0.8 to 4.8) | 52 |

| Enoximone (114, 115, 116, 117, 118 and 119) | 6 (203 [12–114]) | 3.4 (0.5 to 6.3) | 8.7 [4–16] |

| Etanercept (120) | 1 (47) | 4.4 (3.7 to 5.1) | 13 |

| Felodipine (43, 121 and 122) | 3 (532 [20–260]) | 4.0 (1.2 to 6.7) | 30 [12–52] |

| Flosequinan (123 and 124) | 2 (210 [17–193]) | −3.0 (−3.6 to −2.4) | 10 [8–12] |

| Hydralazine-ISDN (16 and 22) | 2 (1,137 [459–678]) | 2.9 (0.8 to 5.0) | 39 [26–52] |

| Ibopamine (125) | 1 (18) | 0.0 (−4.9 to 4.9) | 5 |

| Metoprolol CR (39, 40, 126 and 127) | 4 (587 [41–426]) | 4.5 (1.8 to 7.1) | 25.5 [24–26] |

| Mibefradil (44) | 1 (117) | 0.5 (−2.8 to 3.8) | 26 |

| Milrinone (109) | 1 (108) | 2.2 (1.5 to 2.9) | 53 |

| Moxonidine (128) | 1 (85) | 4.0 (−0.5 to 8.5) | 19 |

| Prazosin (16, 129, 130 and 131) | 4 (523 [22–456]) | 2.5 (0.6 to 4.4) | 28.3 [9–52] |

| Spironolactone (132, 133 and 134) | 3 (185 [37–106]) | 3.0 (1.9 to 4.1) | 25.7 [8–52] |

| Tolvaptan (45) | 1 (240) | 0.8 (−0.3 to 1.9) | 54 |

| Valsartan (38) | 1 (5,010) | 1.3 (0.7 to 1.9) | 78 |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Enalapril was examined separately when studied in patients with asymptomatic LVD, as this was the only trial that exclusively examined patients with asymptomatic LVD.

When >1 trial existed for a specific therapy, meta-analysis was used to calculate the absolute change (Δ) in ejection fraction (EF) compared with placebo (ΔEF = mean net difference in EF between intervention and placebo groups: [intervention EF – baseline] – [placebo EF – baseline], in EF % units).

Table 3.

Absolute Effect of Drug/Device on Change in EDV Compared With Placebo

| Intervention (Ref. #) | No. of Studies (n [Range]) | ΔEDV (95% CI)† | Mean Follow-Up, Weeks [Range] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisoprolol (25 and 41) | 2 (188 [28–160]) | −52.5 (−108.1 to 3.2) | 37 [22–52] |

| Bucindolol (72 and 73) | 2 (188 [49–139]) | −37.1 (−75.8 to 1.6) | 12 |

| CRT (74, 75, 76, 77, 78 and 135) | 5 (1,086 [34–490]) | −31.8 (−33.6 to −30.0) | 19.4 [6–26] |

| Candesartan (79) | 1 (305) | −8.2 (−232.0 to 215.6) | 26 |

| Captopril (81, 82, 83, 85, 136,137 and 138) | 7 (668 [40–298]) | −15.4 (−19.5 to −11.4) | 44.4 [25–52] |

| Carvedilol (85, 86, 88, 89, 90, 91, 95,97, 98, 103 and 139) | 11 (900 [21–415]) | −26.7 (−40.5 to −13.0) | 29.3 [13–52] |

| Digoxin (106 and 108) | 2 (266 [88–178]) | −9.9 (−39.7 to 20.0) | 16 [12–20] |

| Enalapril (20, 42 and 110) | 3 (374 [17–301]) | −11.1 (−20.8 to −1.4) | 30 [12–52] |

| Enalapril-Prev (21) | 1 (108) | −5.0 (−20.0 to 10.0) | 52 |

| Enoximone (114 and 115) | 2 (44 [20–24]) | 31.6 (−85.0 to 148.3) | 10 [4–16] |

| Etanercept (120) | 1 (47) | −18.0 (−22.7 to −13.3) | 13 |

| Felodipine (43 and 122) | 2 (280 [20–260]) | −52.7 (−161.8 to 56.4) | 39 [26–52] |

| Hydralazine-ISDN (22) | 1 (459) | −5.6 (−19.8 to 8.5) | 26 |

| Ibopamine (125) | 1 (18) | 33.9 (−43.8 to 111.5) | 5 |

| Metoprolol CR (39, 126 and 127) | 3 (486 [41–426]) | −27.6 (−63.9 to 8.8) | 24.7 [24–26] |

| Prazosin (129 and 130) | 2 (45 [22–23]) | 4.1 (−50.8 to 59.1) | 17.5 [9–26] |

| Spironolactone (132 and 133) | 2 (143 [37–106]) | −26.9 (−42.3 to −11.5) | 34.5 [17–52] |

| Tolvaptan (45) | 1 (240) | −3.4 (−9.1 to 2.3) | 54 |

| Valsartan (38) | 1 (5,010) | −0.0 (−1.5 to 1.4) | 78 |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Enalapril was examined separately when studied in patients with asymptomatic LVD, as this was the only trial that exclusively examined patients with asymptomatic LVD.

When >1 trial existed for a specific therapy, meta-analysis was used to calculate the absolute change (Δ) in end-diastolic volume (EDV) compared with placebo (ΔEDV = mean net difference in EDV between intervention and placebo groups: [intervention EDV – baseline] – [placebo EDV – baseline], in ml).

Table 4.

Absolute Effect of Drug/Device on Change in ESV Compared With Placebo

| Intervention (Ref. #) | No. of Studies (n [Range]) | ΔESV (95% CI)† | Mean Follow-Up Weeks [Range] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisoprolol (25 and 41) | 2 (188 [28–160]) | −63.0 (−111.1 to −14.9) | 37 [22–52] |

| CRT (74, 75, 76, 77, 78 and 135) | 5 (1,086 [34–490]) | −25.8 (−28.5 to −23.2) | 19.4 [6–26] |

| Candesartan (79) | 1 (305) | −11.3 (−222.8 to 200.1) | 26 |

| Captopril (80, 81, 82, 84, 136,137 and 138) | 7 (668 [40–298]) | −15.7 (−21.9 to −9.6) | 44.4 [25–52] |

| Carvedilol (85, 86, 88, 89, 95, 97,98, 103 and 139) | 9 (852 [21–415]) | −33.9 (−48.4 to −19.3) | 32.2 [13–52] |

| Digoxin (108) | 1 (178) | −19.5 (−40.1 to 1.0) | 12 |

| Enalapril (20 and 42) | 2 (351 [50–301]) | −19.6 (−46.2 to 7.0) | 52 [52] |

| Enalapril-Prev (21) | 1 (108) | −5.0 (−18.6 to 8.6) | 52 |

| Etanercept (120) | 1 (47) | −24.3 (−28.8 to −19.8) | 13 |

| Felodipine (43 and 122) | 2 (280 [20–260]) | −55.4 (−157.1 to 46.4) | 39 [26–52] |

| Hydralazine-ISDN (22) | 1 (459) | −8.8 (−18.4 to 0.8) | 26 |

| Ibopamine (125) | 1 (18) | 28.2 (−48.5 to 104.9) | 5 |

| Metoprolol CR (39 and 127) | 2 (467 [41–426]) | −30.8 (−73.4 to 11.7) | 25 [24–26] |

| Prazosin (129 and 130) | 2 (45 [22–23]) | −4.3 (−62.2 to 53.5) | 17.5 [9–26] |

| Spironolactone (133 and 134) | 2 (143 [37–106]) | −27.7 (−31.3 to −24.0) | 34.5 [17–52] |

| Tolvaptan (45) | 1 (240) | −5.4 (−12.2 to 1.4) | 54 |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Enalapril was examined separately when studied in patients with asymptomatic LVD, as this was the only trial that exclusively examined patients with asymptomatic LVD.

When >1 trial existed for a specific therapy, meta-analysis was used to calculate the absolute change in end-systolic volume (ESV) compared with placebo (ΔESV = mean net difference in ESV between intervention and placebo groups: [intervention ESV – baseline] – [placebo ESV – baseline], in ml).

Change in LVEF and long-term mortality

Placebo-corrected change in LVEF from each individual remodeling trial was plotted against the mortality OR for the specific therapy. There was a significant correlation between short-term therapeutic effect on LVEF and longer-term therapeutic effect on mortality (r = −0.51, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Based on the regression analyses, a 5% increase in the mean EF change corresponded to a relative OR of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.77 to 0.96) for mortality, in other words, toward the favorable direction (p = 0.013).

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. Quantitative Relationship Between Drug/Device Effects on Ejection Fraction and Mortality. Each data point represents a placebo-corrected change in EF from an individual remodeling trial plotted against the mortality OR for the specific therapy. Color-coded mortality effect based on data from mortality trials listed in Table 1. Interventions were classified as favorable if the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio for death from the mortality trials was less than 1, neutral if the confidence interval crossed 1 and adverse if the lower limit of the confidence interval was greater than 1. Remodeling data derived from analysis of 85 RCTs of 25 interventions, including 14,668 total patients. RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; EF = Ejection Fraction

Figure 2B. Predicted Probability of a Categorical Mortality Outcome Based on Drug/Device Effect on Ejection Fraction. The solid lines represent the likelihood of a categorical mortality outcome based on an intervention’s trial-level effect on ejection fraction compared with placebo. The dashed lines signify the corresponding 95% confidence interval. Color-coded mortality effect based on data from mortality trials listed in Table 1. Definition of mortality effect for a given intervention as described in Figure 2A legend. EF = Ejection Fraction

We also evaluated the ability of mean changes in LVEF to categorize interventions as significantly favorable, neutral, and significantly adverse, according to each intervention’s effect on mortality. We found a 4.9-fold increase in the odds of having a favorable mortality outcome (95% CI: 1.2 to 20.3, p = 0.029) for every 5% absolute increase in the mean change in the EF (weighted ordinal logistic regression). Figure 2B shows the predicted probabilities for the effect of a given intervention on long-term mortality based on an intervention’s average effect on EF. In ROC analysis, the AUC for a drug/device-induced change in LVEF to distinguish favorable from neutral or adverse mortality outcomes was 0.71.

Change in LV EDV and long-term mortality

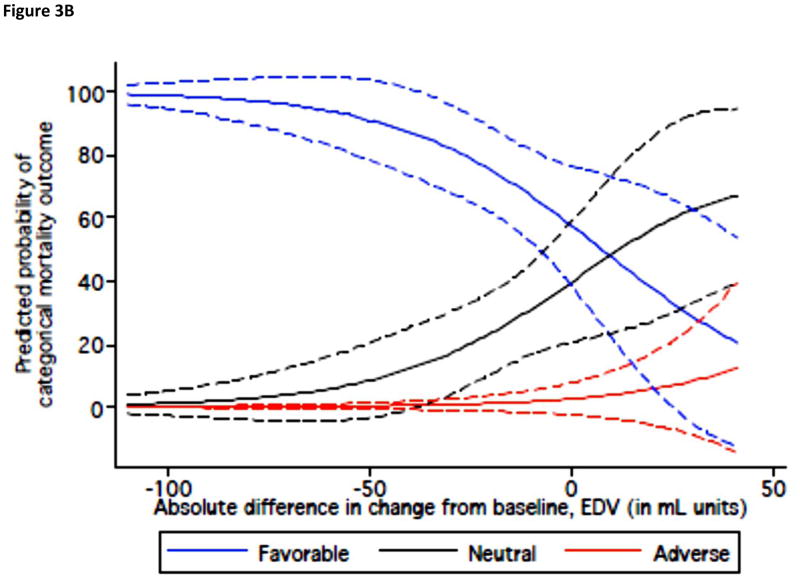

Placebo-corrected change in EDV from each individual remodeling trial was plotted against the mortality OR for the specific therapy. There was a significant correlation between effect sizes in the mortality trials and mean therapy-induced changes in EDV (r = 0.44, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3A). A decrease of 10 ml in the mean change in EDV corresponded to a relative OR of 0.95 for mortality (95% CI: 0.94 to 0.97, p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Figure 3A. Quantitative Relationship Between Drug/Device Effects on End-Diastolic Volume and Mortality. Each data point represents a placebo-corrected change in EDV from an individual remodeling trial plotted against the mortality OR for the specific therapy. Color-coded mortality effect based on data from mortality trials listed in Table 1. Definition of mortality effect for a given intervention as described in Figure 2A legend. Remodeling data derived from analysis of 50 RCTs of 19 interventions, including 8,499 total patients. RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; EDV = End-Diastolic Volume

Figure 3B. Predicted Probability of a Categorical Mortality Outcome Based on Drug/Device Effect on End-Diastolic Volume. The solid lines represent the likelihood of a categorical mortality outcome based on an intervention’s trial-level effect on end-diastolic volume compared with placebo. The dashed lines signify the corresponding 95% confidence interval. Color-coded mortality effect based on data from mortality trials listed in Table 1. Definition of mortality effect for a given intervention as described in Figure 2A legend. EDV = End-Diastolic Volume

A decrease of 10 ml in the mean change of EDV was associated with 1.9-fold (95% CI: 1.2 to 3.2, p = 0.012) increased odds that an intervention would have significantly favorable effects on mortality. Figure 3B shows the predicted probability for therapeutic effects on mortality according to an intervention’s average effect on EDV. In ROC analysis, the AUC for a net change in LV EDV to distinguish favorable from neutral or adverse outcome effects of therapies was 0.76.

Change in LV ESV and long-term mortality

Placebo-corrected change in ESV from each individual remodeling trial was plotted against the mortality OR for the specific therapy. There was a significant correlation between effect sizes in the mortality trials and the effect sizes on ESV in the remodeling studies (r = 0.48, p = 0.002) (Fig. 4A). A decrease of 10 l in the mean ESV change corresponded to a relative OR of 0.96 for mortality (95% CI: 0.93 to 0.98, p = 0.01).

Figure 4.

Figure 4A. Quantitative Relationship Between Drug/Device Effects on End-Systolic Volume and Mortality. Each data point represents a placebo-corrected change in ESV from an individual remodeling trial plotted against the mortality OR for the specific therapy. Color-coded mortality effect based on data from mortality trials listed in Table 1. Definition of mortality effect for a given intervention as described in Figure 2A legend. Remodeling data derived from analysis of 40 RCTs of 16 interventions, including 5037 total patients. RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; ESV = End-Systolic Volume

Figure 4B. Predicted Probability of a Favorable Mortality Outcome Based on Drug/Device Effect on End-Systolic Volume. The solid line represents the likelihood of a favorable mortality outcome based on an intervention’s trial-level effect on end-systolic volume compared with placebo. The dashed lines signify the corresponding 95% confidence interval. There was insufficient remodeling data for ESV to model the probability for neutral or adverse outcomes individually. Color-coded mortality effect based on data from mortality trials listed in Table 1. Definition of mortality effect for a given intervention as described in Figure 2A legend. ESV = End-Systolic Volume

Logistic regression analyses suggested a significant association between the mean change in ESV due to therapy and effects on mortality, based on a per 10-ml decrease in the mean change in ESV (OR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.53 to 0.60). Figure 4B shows the predicted probability for favorable effects on mortality according to an intervention’s average effect on ESV. In ROC analysis, the AUC to distinguish favorable from neutral or adverse therapies was 0.73. It is noted from Table 4 that there are fewer published data on drug/device effects on ESV compared to data on LVEF or EDV, particularly for interventions that were found to have neutral or adverse mortality effects. For this reason, there was insufficient remodeling data for ESV to model the probability for neutral or adverse outcomes individually.

Secondary analyses

Adjustments for the average LVEF, EDV, or ESV at baseline (as applicable in the corresponding analyses) and follow-up duration in the remodeling trials resulted in very similar estimates as the main analysis (data not shown). The same was true for the unweighted versions of the regression analyses. Eliminating the shorter-term remodeling studies (6 studies in which the follow-up was <12 weeks) resulted in very similar correlation estimates between the mortality OR and the placebo-corrected change in remodeling outcomes, without inferential changes (EF −0.51, p < 0.001; EDV 0.40, p = 0.009; ESV 0.44, p = 0.007).

Mean changes in EDV and ESV (without transformation from dimensions) were reported only in 14 studies. We calculated mean changes in the EDV from corresponding changes in diameters or indices for 35 of 49 studies, and in ESV for 26 of 40 studies with available data. After excluding studies in which we performed transformations, all results of the ESV and EDV metrics became statistically not significant, with substantial loss of data.

Results similar to the main analysis were seen when we used meta-analysis–derived summary estimates of the effects on LVEF, EDV, and ESV, instead of considering multiple studies on the same intervention separately. However, the correlation between long-term effects on mortality and ESV was no longer significant (p = 0.09).

Discussion

The results of the present study demonstrate a significant association between short-term trial-level therapeutic effects of a drug or device on parameters of LV remodeling and longer-term trial-level therapeutic effects on mortality in LVD. Furthermore, these drug/device-induced changes in ventricular remodeling reflect the probability of a categorical mortality outcome (favorable, neutral, adverse) for those therapies.

Several individual therapeutic agents with favorable effects on remodeling, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (20 and 42) and beta-adrenergic blockers (85), are associated with favorable effects on clinical outcomes in HF trials. Conversely, agents such as omapatrilat (5 and 6) or ibopamine (62 and 125) with neutral or adverse effects on remodeling relative to a comparator have been found to be associated with neutral or adverse effects on clinical outcomes. In distinct trials, the vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist tolvaptan was shown to have a neutral effect on both ventricular remodeling and long-term clinical outcomes (45 and 67).

Based in part on such data, it is widely conceptualized that ventricular remodeling is biologically related to and involved in the progression of HF (140 and 141). The relationship is not consistently demonstrated, however. Bozkurt et al. (120) showed a dose-dependent reverse remodeling effect over 3 months with etanercept, a cytokine inhibitor. Three years later, a much larger long-term study failed to show any long-term clinical outcome benefit (4).

The morbidity and mortality associated with HF result from a multifactorial and complex process unlikely to be wholly captured by change in a single volume measurement or serologic parameter (7 and 142). Although some events that impact clinical course are plausibly related to remodeling (such as hospitalization for HF or risk of sudden death), other mortal events, such as acute myocardial infarction, are likely less related. Thus, the expectation that a single surrogate marker could predict the effects of a drug or device on clinical outcomes with high precision is unrealistic. For this reason, we recognize that the effect of a drug or device on LV remodeling, or on any single parameter for that matter, is unlikely to achieve the level of precision discussed by Prentice (143) or by Fleming and DeMets (144) as a valid surrogate marker for mortality in HF. Rather, the data from this analysis suggest that drug/device effects on remodeling should be viewed as suggestive of the intervention’s potential effect on mortality. Given the demonstrated proportional relationship between drug/device effects on short-term ventricular remodeling and long-term mortality, it is reasonable to conclude that the effects of a drug or device on LV remodeling can be taken into consideration during the development process of novel therapeutic agents for HF, in creating a probability signal of the likelihood of a favorable, neutral, or adverse effect of the therapy being investigated on longer-term mortality outcomes.

Study limitations

There are important limitations to this analysis. Inherent in this retrospective analysis of prospective studies are both publication bias and selection bias. To avoid within-trial selection biases, we used only randomized trials that fit rigorous inclusion criteria (recognizing that some potentially relevant works might be excluded from the analysis). Publication bias poses threats to all meta-epidemiological studies, including this study. It may be less of a problem for the mortality trials, because large RCTs may be published irrespective of their findings. Even if publication bias is a problem for remodeling trials, it is unclear whether it would affect the associations described, and to which direction. Nonpublication of neutral remodeling trials would have no systematic effect on our results for interventions with a neutral effect on mortality, but it would bias our results away from the null for interventions with adverse or favorable effects on mortality. Moreover, published studies of remodeling are analyses of “completers,” that is, patients who have both baseline and final data for analysis. It is difficult to predict the effect of the “noncompleters” on the analysis if their information was available. If anything, data from noncompleters would attenuate the average EF, EDV, or ESV changes toward the unfavorable direction. It is likely that this shift would be influential only if a substantial proportion of patients had died in the remodeling studies. The median proportion of deaths in the remodeling studies was 3.6%, (25th and 75th quartiles, 0% and 8.3%, respectively) among 79 trials that report this information. These numbers suggest that the effects of noncompleters on our analyses would not likely be dramatic.

Second, most data pertain to EF. We approximated changes in LV volume-related outcomes (EDV, ESV) from data on LV indexes and diameters in the majority of pertinent studies. As discussed in Methods, the concordance of the approximations and the derived data was not good in a small number of examples. All analyses were nonsignificant among the 14 trials that directly reported EDV and ESV measurements, but this could be attributed to substantial loss of statistical power. Therefore, results on LV volumes should be viewed with caution, and there are insufficient data to draw any conclusions regarding which of the parameters in this analysis may best correlate with mortality outcomes. Additionally, most of the trials evaluated remodeling using radionuclide ventriculography or 2-dimensional echocardiography. In clinical practice, 2-dimensional echocardiography, with its inherent limitations, is predominantly utilized. While we recognize that more contemporary techniques, such as 3-dimensional echocardiography, contrast echocardiography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging would more precisely measure volumes, these techniques have not as yet been widely deployed for use in multicenter trials, and were not used for the drugs and devices that were included in this analysis.

Third, we grouped results from trials spanning different therapeutic eras and were heterogeneous in their follow-up duration, ranging from 4 weeks to >1 year. This was expected, as there is no generally established time frame for the ideal assessment of an intervention’s effect on ventricular remodeling. External validation is not yet available for these results that represent the current published literature.

Fourth, our analyses are sensitive to confounding and to ecological fallacies. Ideally, we would associate changes in the remodeling outcomes and corresponding changes in the clinical outcomes measured in the same patients. If individual patient data are available, one can use structural equation modeling or path analysis methodologies. If sufficient summary statistics are available, one can use specially developed meta-analytic techniques (145). However, in most cases, including the current one, such data are not available. We believe that even ecological associations are of interest because they can help formulating hypotheses for further study.

In addition, we acknowledge that our analyses do not prove the validity of remodeling outcomes as surrogate outcomes for mortality in LVD, as defined by others (143 and 144), and indeed, we believe the data suggest that no serum biomarker or cardiac structural marker will do so, given the complexity of the HF syndrome. Rather, the data suggest a quantifiable association of a marker such as remodeling and a longer-term outcome such as mortality, which may be a useful signal in the therapeutic development process. We acknowledge the possibility that there is indeed a stronger relationship between remodeling and mortality, and that the limitations of our approach given the available data obfuscate our ability to discern such a relationship, particularly within an individual intervention. The modest correlation of the remodeling effect of interventions with the mortality effect seen in this analysis is influenced by both the underlying inherent relation between the therapeutic effect on remodeling on mortality, as well as the fact that different interventions will have various proportions of their effect mediated through a remodeling mechanism.

Finally, the analyses of changes in LVEF and volumes reported in the literature and summarized here do not allow a clear distinction between a simple functional change in EF or volumes and a true long-term structural change in the underlying LV architecture resulting from therapy (what would truly be considered remodeling). To assess the latter, a study design needs to include a “withdrawal” study, in which EF and volumes are reassessed after withdrawal of drug or device influence. Some published studies indeed report such results (20, 21 and 45), although the vast majority of remodeling studies do not.

Conclusions

Hence, based on analysis of the current literature investigating patients with LVD, there is a significant correlation and a salient predictability signal between short-term trial-level therapeutic effects on LV remodeling and longer-term trial-level therapeutic effects on mortality. Our findings indicate that the effect of a drug or device on LV remodeling can be viewed as a probability signal of outcome effects of those therapies during the development process of novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of HF, rather than as a precise surrogate. Although no surrogate end point, alone, will ever fully substitute for a mortality assessment, our findings of an increased probability of a survival benefit for an intervention associated with improvements in remodeling parameters imply that the demonstration of favorable remodeling renders a survival signal more credible. Moreover, further development of this dataset may allow for quantitative modeling to predict a new agent’s likelihood of mortality benefit given the agent’s short-term effect on remodeling parameters.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Disclosures

This article was partially funded by the grant NIH/NCRR UL1RR025752, Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr. Konstam is a consultant for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Trevena, Johnson & Johnson, Cardioxyl, Merck, and Forest. Dr. Udelson is a consultant for Cytori, Angioblast, and Medtronic.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to this manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Konstam MA, Udelson JE, Anand IS, Cohn JN. Ventricular remodeling in heart failure: a credible surrogate end point. J Card Fail. 2003;9:350–3. doi: 10.1054/j.cardfail.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalra PR, Moon JC, Coats AJ. Do results of the ENABLE (Endothelin Antagonist Bosentan for Lowering Cardiac Events in Heart Failure) study spell the end for non-selective endothelin antagonism in heart failure? Int J Cardiol. 2002;85:195–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand I, McMurray J, Cohn JN, et al. Long-term effects of darusentan on left-ventricular remodelling and clinical outcomes in the Endothelin A Receptor Antagonist Trial in Heart Failure (EARTH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:347–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16723-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann DL, McMurray JJ, Packer M, et al. Targeted anticytokine therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the Randomized Etanercept Worldwide Evaluation (RENEWAL) Circulation. 2004;109:1594–602. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124490.27666.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Packer M, Califf RM, Konstam MA, et al. Comparison of omapatrilat and enalapril in patients with chronic heart failure: the Omapatrilat Versus Enalapril Randomized Trial of Utility in Reducing Events (OVERTURE) Circulation. 2002;106:920–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029801.86489.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rouleau JL, Pfeffer MA, Stewart DJ, et al. Comparison of vasopeptidase inhibitor, omapatrilat, and lisinopril on exercise tolerance and morbidity in patients with heart failure: IMPRESS randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:615–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Udelson JE, Konstam MA. Relation between left ventricular remodeling and clinical outcomes in heart failure patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail. 2002;8 (Suppl):465–71. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, Brandt PW, Whitlock RM, Wild CJ. Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1987;76:44–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong M, Johnson G, Shabetai R, et al. Echocardiographic variables as prognostic indicators and therapeutic monitors in chronic congestive heart failure. Veterans Affairs cooperative studies V-HeFT I and II. V-HeFT VA Cooperative Studies Group. Circulation. 1993;87 (Suppl 6):65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong M, Staszewsky L, Latini R, et al. Severity of left ventricular remodeling defines outcomes and response to therapy in heart failure: valsartan heart failure trial (Val-HeFT) echocardiographic data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2022–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohn JN, Rector TS. Prognosis of congestive heart failure and predictors of mortality. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:A25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(88)80081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keogh AM, Baron DW, Hickie JB. Prognostic guides in patients with idiopathic or ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy assessed for cardiac transplantation. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:903–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91434-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor GJ, Humphries JO, Mellits ED, et al. Predictors of clinical course, coronary anatomy and left ventricular function after recovery from acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1980;62:960–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.5.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanz G, Castaner A, Betriu A, et al. Determinants of prognosis in survivors of myocardial infarction: a prospective clinical angiographic study. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1065–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198205063061801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cintron G, Johnson G, Francis G, Cobb F, Cohn JN for the V-HeFT VA Cooperative Studies Group. Prognostic significance of serial changes in left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1993;87(Suppl):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohn JN, Archibald DG, Ziesche S, et al. Effect of vasodilator therapy on mortality in chronic congestive heart failure. Results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1547–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606123142404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh SN, Fletcher RD, Fisher SG, et al. Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia. Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:77–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507133330201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohn JN, Tognoni G for the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1667–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial Investigators. . A trial of the beta-blocker bucindolol in patients with advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1659–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konstam MA, Rousseau MF, Kronenberg MW, et al. for the SOLVD Investigators. Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril on the long-term progression of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1992;86:431–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstam MA, Kronenberg MW, Rousseau MF, et al. for the SOLVD (Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction) Investigators. . Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril on the long-term progression of left ventricular dilatation in patients with asymptomatic systolic dysfunction. Circulation. 1993;88:2277–83. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohn JN, Tam SW, Anand IS, et al. Isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in a fixed-dose combination produces further regression of left ventricular remodeling in a well-treated black population with heart failure: results from A-HeFT. J Card Fail. 2007;13:331–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colucci WS, Packer M, Bristow MR, et al. for the US Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. Carvedilol inhibits clinical progression in patients with mild symptoms of heart failure. Circulation. 1996;94:2800–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doughty RN, Whalley GA, Gamble G, MacMahon S, Sharpe N. Effects of carvedilol on left ventricular regional wall motion in patients with heart failure caused by ischemic heart disease. Australia New Zealand Heart Failure Research Collaborative Group. J Card Fail. 2000;6:11–8. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(00)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lechat P, Escolano S, Golmard JL, et al. Prognostic value of bisoprolol-induced hemodynamic effects in heart failure during the Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study (CIBIS) Circulation. 1997;96:2197–205. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Holbrook A, McAlister FA. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XIX. Applying clinical trial results. A. How to use an article measuring the effect of an intervention on surrogate end points. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1999;282:771–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.8.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonopoulos GV, Lau J, Konstam MA, Udelson JE. Are drug induced changes in left ventricular ejection fraction or volumes adequate surrogates for long-term natural history outcomes in heart failure? Circulation. 1999;100:I296. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal R. Parametric Measures of Effect Size. In: Cooper HH, editor. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trial. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:820–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a metaanalysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cramer H. Princeton Landmarks in Mathematics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1999. Mathematical Methods of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teichholz LE, Kreulen T, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Problems in echocardiographic volume determinations: echocardiographic angiographic correlations in the presence of absence of asynergy. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosteller RD. Simplified calculation of body-surface area. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198710223171717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Mean body weight, height, and body mass index, United States 1960–2002. Adv Data. 2004;347:17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong M, Staszewsky L, Latini R, et al. Valsartan benefits left ventricular structure and function in heart failure: Val-HeFT echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:9707–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groenning BA, Nilsson JC, Sondergaard L, Fritz-Hansen T, Larsson HB, Hildebrandt PR. Antiremodeling effects on the left ventricle during beta-blockade with metoprolol in the treatment of chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:20727–80. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein S, Kennedy HL, Hall C, et al. Metoprolol CR/XL in patients with heart failure: a pilot study examining the tolerability, safety, and effect on left ventricular ejection fraction. Am Heart J. 1999;138:11587–65. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubach P, Myers J, Bonetti P, et al. Effects of bisoprolol fumarate on left ventricular size, function, and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure: analysis with magnetic resonance myocardial tagging. Am Heart J. 2002;143:6767–83. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.121269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenberg B, Quinones MA, Koilpillai C, et al. Effects of long-term enalapril therapy on cardiac structure and function in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Results of the SOLVD echocardiography substudy. Circulation. 1995;91:25737–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.10.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong M, Germanson T, Taylor WR, et al. Felodipine improves left ventricular emptying in patients with chronic heart failure: V-HeFT III echocardiographic substudy of multicenter reproducibility and detecting functional change. J Card Fail. 2000;6:197–28. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(00)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levine TB, Bernink PJ, Caspi A, et al. Effect of mibefradil, a T-type calcium channel blocker, on morbidity and mortality in moderate to severe congestive heart failure: the MACH-1 study. Mortality Assessment in Congestive Heart Failure Trial. Circulation. 2000;101:7587–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.7.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Udelson JE, McGrew FA, Flores E, et al. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effect of oral tolvaptan on left ventricular dilation and function in patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:21517–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Packer M, O’Connor CM, Ghali JK, et al. the Prospective Randomized Amlodipine Survival Evaluation Study Group. . Effect of amlodipine on morbidity and mortality in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1107–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.CIBIS-II Investigators. . The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, et al. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet. 2003;362:772–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McMurray JJ, Ostergren J, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trial. Lancet. 2003;362:767–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, et al. the SAVE Investigators. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. for the U S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1349–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Packer M, Coats AJ, Fowler MB, et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1651–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1385–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The Digitalis Investigation Group. . The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.The SOLVD Investigators. . Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The SOLVD Investigators. . Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:685–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cleland JG, Coletta AP, Lammiman M, et al. Clinical trials update from the European Society of Cardiology meeting 2005: CARE-HF extension study, ESSENTIAL, CIBIS-III, S-ICD, ISSUE-2, STRIDE-2, SOFA, IMAGINE, PREAMI, SIRIUS-II and ACTIVE. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:1070–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohn JN, Ziesche S, Smith R, et al. for the Vasodilator-Heart Failure Trial (V-HeFT) Study Group. . Effect of the calcium antagonist felodipine as supplementary vasodilator therapy in patients with chronic heart failure treated with enalapril: V-HeFT III. Circulation. 1997;96:856–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeMets DL. Design of phase II trials in congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2000;139 (Suppl):207–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, et al. Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2049–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hampton JR, van Veldhuisen DJ, Kleber FX, et al. Second Prospective Randomised Study of Ibopamine on Mortality and Efficacy (PRIME II) Investigators. . Randomised study of effect of ibopamine on survival in patients with advanced severe heart failure. Lancet. 1997;349:971–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)10488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hjalmarson A, Goldstein S, Fagerberg B, et al. for the MERIT-HF Study Group. . Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and well-being in patients with heart failure: the Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF) JAMA. 2000;283:1295–302. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.10.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Packer M, Carver JR, Rodeheffer RJ, et al. for the PROMISE Study Research Group. . Effect of oral milrinone on mortality in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1468–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohn JN, Pfeffer MA, Rouleau J, et al. Adverse mortality effect of central sympathetic inhibition with sustained-release moxonidine in patients with heart failure (MOXCON) Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:659–67. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M, Burnett JC, Jr, et al. Effects of oral tolvaptan in patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure: the EVEREST outcome trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1319–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamer AW, Arkles LB, Johns JA. Beneficial effects of low dose amiodarone in patients with congestive cardiac failure: a placebo controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:1768–74. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Navarro-Lopez F, Cosin J, Marrugat J, Guindo J, Bayes de Luna A for the SSSD Investigators. Comparison of the effects of amiodarone versus metoprolol on the frequency of ventricular arrhythmias and on mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Spanish Study on Sudden Death. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:1243–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90291-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Udelson JE, DeAbate CA, Berk M, et al. Effects of amlodipine on exercise tolerance, quality of life, and left ventricular function in patients with heart failure from left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Am Heart J. 2000;139:503–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pollock SG, Lystash J, Tedesco C, Craddock G, Smucker ML. Usefulness of bucindolol in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:603–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90488-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Woodley SL, Gilbert EM, Anderson JL, et al. Beta-blockade with bucindolol in heart failure caused by ischemic versus idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1991;84:2426–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.6.2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bristow MR, O’Connell JB, Gilbert EM, et al. for the Bucindolol Investigators. . Dose-response of chronic beta-blocker treatment in heart failure from either idiopathic dilated or ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1994;89:1632–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saxon LA, De Marco T, Schafer J, et al. Effects of long-term biventricular stimulation for resynchronization on echocardiographic measures of remodeling. Circulation. 2002;105:1304–10. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.St John Sutton MG, Plappert T, Abraham WT, et al. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy on left ventricular size and function in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:1985–90. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065226.24159.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Higgins SL, Hummel JD, Niazi IK, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy for the treatment of heart failure in patients with intraventricular conduction delay and malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1454–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abraham WT, Young JB, Leon AR, et al. Effects of cardiac resynchronization on disease progression in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, an indication for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, and mildly symptomatic chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:2864–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146336.92331.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Matsumori A the Assessment of Response to Candesartan in Heart Failure in Japan (ARCH-J) Study Investigators. . Efficacy and safety of oral candesartan cilexetil in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:669–77. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.The Captopril Multicenter Research Group. . A placebo-controlled trial of captopril in refractory chronic congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;2:755–63. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sharpe N, Murphy J, Smith H, Hannan S. Treatment of patients with symptomless left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988;1:255–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ray SG, Pye M, Oldroyd KG, et al. Early treatment with captopril after acute myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1993;69:215–22. doi: 10.1136/hrt.69.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gotzsche CO, Sogaard P, Ravkilde J, Thygesen K. Effects of captopril on left ventricular systolic and diastolic function after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:156–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)91268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.The Captopril-Digoxin Multicenter Research Group. . Comparative effects of therapy with captopril and digoxin in patients with mild to moderate heart failure. JAMA. 1988;259:539–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Keren G, Pardes A, Eschar Y, et al. One-year clinical and echocardiographic follow-up of patients with congestive cardiomyopathy treated with captopril compared to placebo. Isr J Med Sci. 1994;30:90–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Doughty RN, Whalley GA, Gamble G, MacMahon S, Sharpe N. Left ventricular remodeling with carvedilol in patients with congestive heart failure due to ischemic heart disease. Australia-New Zealand Heart Failure Research Collaborative Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1060–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Quaife RA, Gilbert EM, Christian PE, et al. Effects of carvedilol on systolic and diastolic left ventricular performance in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy or ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:779–84. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Krum H, Sackner-Bernstein JD, Goldsmith RL, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the long-term efficacy of carvedilol in patients with severe chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1995;92:1499–506. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.6.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Australia-New Zealand Heart Failure Research Collaborative Group. . Effects of carvedilol, a vasodilator-beta-blocker, in patients with congestive heart failure due to ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Basu S, Senior R, Raval U, van der Does R, Bruckner T, Lahiri A. Beneficial effects of intravenous and oral carvedilol treatment in acute myocardial infarction. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Circulation. 1997;96:183–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Olsen SL, Gilbert EM, Renlund DG, Taylor DO, Yanowitz FD, Bristow MR. Carvedilol improves left ventricular function and symptoms in chronic heart failure: a double-blind randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1225–31. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00012-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Metra M, Nardi M, Giubbini R, Dei Cas L. Effects of short- and long-term carvedilol administration on rest and exercise hemodynamic variables, exercise capacity and clinical conditions in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:1678–87. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Krum H, Gu A, Wilshire-Clement M, et al. Changes in plasma endothelin-1 levels reflect clinical response to beta-blockade in chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 1996;131:337–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cleland JG, Pennell DJ, Ray SG, et al. Myocardial viability as a determinant of the ejection fraction response to carvedilol in patients with heart failure (CHRISTMAS trial): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chizzola PR, Goncalves de Freitas HF, Marinho NV, Mansur JA, Meneghetti JC, Bocchi EA. The effect of beta-adrenergic receptor antagonism in cardiac sympathetic neuronal remodeling in patients with heart failure. In J Cardiol. 2006;106:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Palazzuoli A, Quatrini I, Vecchiato L, et al. Left ventricular diastolic function improvement by carvedilol therapy in advanced heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;45:563–8. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000159880.12067.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lowes BD, Gill EA, Abraham WT, et al. Effects of carvedilol on left ventricular mass, chamber geometry, and mitral regurgitation in chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1201–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cohen Solal A, Jondeau G, Beauvais F, Berdeaux A. Beneficial effects of carvedilol on angiotensin-converting enzyme activity and renin plasma levels in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:463–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Palazzuoli A, Bruni F, Puccetti L, et al. Effects of carvedilol on left ventricular remodeling and systolic function in elderly patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4:765–70. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bristow MR, Gilbert EM, Abraham WT, et al. for the MOCHA Investigators. . Carvedilol produces dose-related improvements in left ventricular function and survival in subjects with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1996;94:2807–816. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Packer M, Colucci WS, Sackner-Bernstein JD, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of carvedilol in patients with moderate to severe heart failure. The PRECISE trial. Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Carvedilol on Symptoms and Exercise. Circulation. 1996;94:2793–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cohn JN, Fowler MB, Bristow MR, et al. for the U S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. Safety and efficacy of carvedilol in severe heart failure. J Card Fail. 1997;3:173–9. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(97)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hori M, Sasayama S, Kitabatake A, et al. Low-dose carvedilol improves left ventricular function and reduces cardiovascular hospitalization in Japanese patients with chronic heart failure: the Multicenter Carvedilol Heart Failure Dose Assessment (MUCHA) trial. Am Heart J. 2004;147:324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Guazzi M, Agostoni P, Matturri M, Pontone G, Guazzi MD. Pulmonary function, cardiac function, and exercise capacity in a follow-up of patients with congestive heart failure treated with carvedilol. Am Heart J. 1999;138:460–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tatli E, Kurum T. A controlled study of the effects of carvedilol on clinical events, left ventricular function and proinflammatory cytokines levels in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:344–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hassapoyannes CA, Easterling BM, Chavda K, Chavda KK, Movahed MR, Welch GW. The effect of chronic digitalization on pump function in systolic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3:593–9. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Uretsky BF, Young JB, Shahidi FE, Yellen LG, Harrison MC, Jolly MK for the PROVED Investigative Group. . Randomized study assessing the effect of digoxin withdrawal in patients with mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure: results of the PROVED trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:955–62. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90403-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kostis JB, Rosen RC, Cosgrove NM, Shindler DM, Wilson AC. Nonpharmacologic therapy improves functional and emotional status in congestive heart failure. Chest. 1994;106:996–1001. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Packer M, Gheorghiade M, Young JB, et al. Withdrawal of digoxin from patients with chronic heart failure treated with angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors. RADIANCE study. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307013290101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.DiBianco R, Shabetai R, Kostuk W, Moran J, Schlant RC, Wright R. A comparison of oral milrinone, digoxin, and their combination in the treatment of patients with chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:677–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903163201101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Franciosa JA, Wilen MM, Jordan RA. Effects of enalapril, a new angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, in a controlled trial in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:101–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Webster MW, Fitzpatrick MA, Hamilton EJ, et al. Effects of enalapril on clinical status, biochemistry, exercise performance and haemodynamics in heart failure. Drugs. 1985;30 (Suppl 1):74–81. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198500301-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McGrath BP, Arnolda L, Matthews PG, et al. Controlled trial of enalapril in congestive cardiac failure. Br Heart J. 1985;54:405–14. doi: 10.1136/hrt.54.4.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jennings G, Kiat H, Nelson L, Kelly MJ, Kalff V, Johns J. Enalapril for severe congestive heart failure. A double-blind study. Med J Aust. 1984;141:723–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jondeau G, Dubourg O, Delorme G, et al. Oral enoximone as a substitute for intravenous catecholamine support in end-stage congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:242–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]