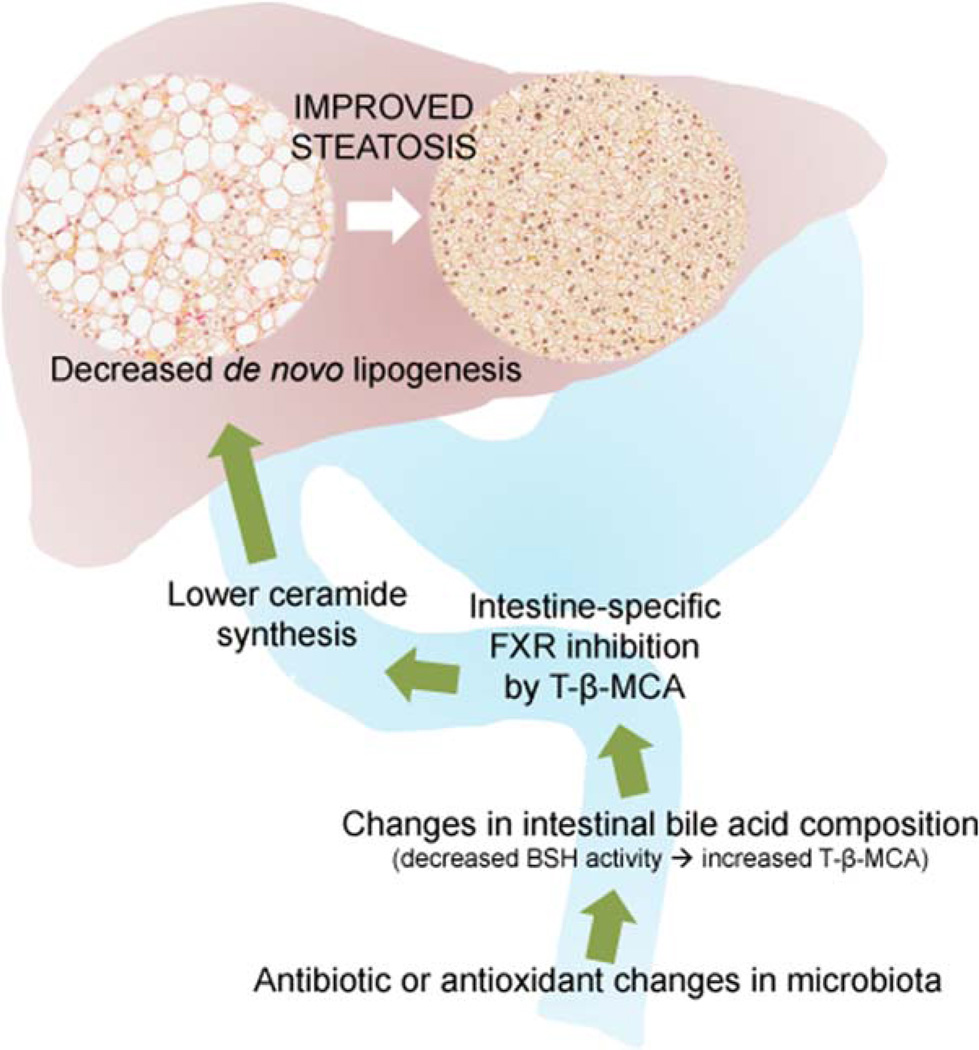

A new wrinkle in the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) story suggests that FXR antagonism may be beneficial for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). In a recent article, Jiang et al. show that modulating the gut microbiota with either an antioxidant or -biotics changes intestinal bile acid composition and inhibits intestinal, but not hepatic, FXR signaling.1 These treatments also reduced circulating levels of the class of waxy lipids known as ceramides, as well as de novo lipogenesis, in the liver (Fig. 1). The net result is a profound and surprising improvement in hepatic steatosis (HS). This work also identifies a novel relationship between FXR and ceramides. Using a sophisticated, unbiased lipidomic approach, the researchers show that altering the gut microbiome in mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) greatly increases intestinal levels of tauro-β-muricholic acid (T-β-MCA). Normally, this bile acid is metabolized by the microbiota through deconjugation of the taurine into β-MCA by bacterial bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity in the distal ileum. Treating mice with either an antioxidant (tempol) or depleting the gut bacteria with antibiotics resulted in loss of BSH activity and accumulation of its substrate, T-β-MCA. T-β-MCA directly inhibits intestinal FXR signaling, as shown through the decrease in ileal expression of FXR target genes Shp and Fgf15. Using conditional intestinal Fxr-null mice (FxrΔIE), the researchers convincingly demonstrate that decreased HS in this model is specifically dependent on intestinal, not hepatic, FXR.

Fig. 1.

Intestinal FXR inhibition diminishes hepatic de novo lipogenesis. Shown in graphical form are the major findings of the work by Jiang et al.1 Changes to the intestinal flora in the distal small bowel (bottom of figure) occur when antibiotics or -oxidants are applied to mice. A particular consequence of this is a reduction in bacterial BSH activity that normally metabolizes tauro-conjugated bile acids. This produces increased levels of T-β-MCA in the distal ileum. In turn, T-β-MCA inhibits intestinal FXR signaling that normally helps drive ceramide synthesis. FXR-specific inhibition by T-β-MCA decreases the transit of ceramides through the enterohepatic circulation to the liver. Because ceramides promote hepatic de novo lipogenesis, the net effect of reduced ceramide flux to the liver is a reduction in HS.

Fatty liver ranges from simple steatosis (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NAFLD) to inflammatory NASH. Those with NASH are at high risk for progression to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation (LT). NASH is soon likely to be the most common reason for LT. Unfortunately, lifestyle intervention alone is unlikely to reverse NASH fibrosis and so the clamor for pharmacological interventions is reaching a fever pitch. Vitamin E and thiazolidinediones, which are nuclear receptor agonists, have some efficacy, but we are still waiting for a bona-fide medical home run for the treatment of NAFLD/NASH.

Many nuclear receptors function as ligand-activated transcription factors, and several of them have endogenous nutrients or lipids as their natural ligands. Recent interest has centered on FXRs, which are highly expressed in hepato- and enterocytes of the small intestine. FXR regulates genes controlling bile acid synthesis in the liver and enterohepatic recycling of bile acids. Bile acids are the natural ligands for FXR, and their net effect is feedback inhibition of many bile acid synthetic genes, including CYP7A1, the rate-limiting enzyme for bile acid synthesis from cholesterol. This repression is accomplished, in part, when luminal bile acids activate FXR in the distal ileum and cause enterocyte release of fibroblast growth factor (FGF)15/19 (Fgf15 in mice, FGF19 in humans). FGF15/19 is a circulating hormone that acts in the liver to inhibit CYP7A1, thereby closing the enterohepatic loop of bile acids and demonstrating that the gut is truly an endocrine organ.2 But will systemic FXR agonism have long-term efficacy and safety in NASH? Our first clinical taste of FXR agonism is bittersweet. The long-anticipated FLINT trial tested obeticholic acid, a synthetic FXR agonist, in biopsy-proven, nondiabetic NASH.3 Although the primary histological endpoint was met, there was no difference in complete resolution of NASH, only a trivial improvement in fibrosis, and a high rate of side effects. We are naturally left to puzzle about whether systemic FXR agonism will ever pay off in NAFLD/NASH.

Despite the robust experimental approach by Jiang et al., it is important to recognize that rodents and humans have significant differences in bile acid metabolism. Humans do not synthesize muricholic acid or T-β-MCA, which raises the question of whether the same intestinal FXR-ceramide-liver axis even exists in our species. If it does, then searching for a bile acid that is structurally or functionally similar to T-β-MCA in the human ileum might be worthwhile.

The work of Jiang et al. also suggests that ceramides have a major impact on hepatic de novo lipogenesis. The strongest known physiological stimuli for hepatic de novo lipogenesis are insulin and sterols, through liver X receptors (LXRs). Both drive the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) pathway for lipid synthesis in the liver. The same group previously showed that their tempol model reduced HFD-induced obesity and insulin resistance (IR) by intestinal FXR inhibition.4 But in that setting, fasting insulin levels were 50% lower in FxrΔIE mice on an HFD.4 Therefore, it is unclear how much of the steatosis effect reported now by Jiang et al. is owing to decreased insulin-dependent SREBP-1c responses and how much can really be ascribed to the action of ceramides. In a separate study, FxrΔIE mice were not protected from mild HS when kept on a 1% cholesterol diet for 28 days, suggesting that LXR signaling is the dominant effect.5 Myriocin, a known antagonist of ceramide synthesis, could help tease apart the relative effects of insulin and ceramides on HS. Ceramides have also been reported to directly impact sterol sensing in the endoplasmic reticulum membranes and SREBP cleavage,6 but this is not known to be an FXR-dependent effect. The researchers also could have strengthened the causal association of ceramides with hepatic lipogenesis by reintroducing ceramides into intestinal FXR-null mice, which should presumably reverse the improved hepatic phenotype.

The bile acid milieu of the distal ileum is complicated and it is unclear what the dynamic is between FXR agonists and antagonists in this specific tissue. Mice with a global deletion of FXR develop HS and liver damage later in life, despite improved glucose tolerance and reduced adiposity. FXRs are also required for the weight loss and metabolic improvement after vertical sleeve gastrectomy. 7 Even oral administration of an intestine-specific FXR agonist, fexaramine, inhibited diet-induced obesity and HS.8 Although obeticholic acid may not turn out to be a NASH champion, the FLINT trial does provide evidence in humans that FXR agonism improves HS. These findings run counter to the model put forth by Jiang et al. suggesting that intestinal FXR agonism should worsen (or at least not improve) steatosis. A broader question is whether all bile acid agonists of FXR have equivalent effects on ceramide synthesis? Perhaps a mixed FXR agonist/antagonist delivered to the distal ileum would be most beneficial for NASH. In other settings, seemingly opposing actions on the same nuclear receptor in different tissues turn out to have overall beneficial clinical effects. For example, raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, has proestrogen effects on bone and antiestrogen effects on uterus and breast.

Another strength of the work by Jiang et al. is the identification of an unexpected lipid (ceramide) connection between the gut and the liver. If ceramides are important lipid mediators for NASH, then what is the correct pharmacological target: intestinal FXR, circulating ceramides themselves, or the bile salt, hydrolase, in the distal ileum? Theoretically, myriocin might be a useful treatment for NAFLD/NASH, but it is a fungal-derived immunosuppressant, as with cyclosporine. Would the benefit be worth the likely side effects of a chronic treatment? A derivative of myriocin, fingolimod, is currently used to treat multiple sclerosis. It would be interesting to know, on a weight- and diabetes-controlled basis, whether patients receiving fingolimod have a reduction in HS.

Finally, the real clinical problem in NAFLD/NASH is the chronic fibrosis that becomes cirrhosis. Ameliorating lipotoxicity, inflammation, and IR from excess ceramides might be an important therapeutic target in NASH, but we also need to see significant long-term decreases in fibrosis with minimal side effects before getting behind FXR antagonists, agonists, or a combination of both. This article is exciting because it shows that we can alter hepatic physiology using metabolism at a distance, in this case from the distal ileum. Intestine-specific modulation of FXR triggers a broad metabolic improvement and might be a better strategy than systemic agonism in the treatment of NAFLD/NASH and metabolic syndrome.1,8

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Jiang C, Xie C, Li F, Zhang L, Nichols RG, Krausz KW, et al. Intestinal farnesoid X receptor signaling promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:386–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI76738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, Peng L, Cummins CL, McDonald JG, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;2:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, Abdelmalek MF, et al. NASH Clinical Research Network. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:956–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li F, Jiang C, Krausz KW, Li Y, Albert I, Hao H, et al. Microbiome remodelling leads to inhibition of intestinal farnesoid X receptor signalling and decreased obesity. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2384. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt J, Kong B, Stieger B, Tschopp O, Schultze SM, Rau M, et al. Protective effects of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) on hepatic lipid accumulation are mediated by hepatic FXR and independent of intestinal FGF15 signal. Liver Int. 2015;35:1133–1144. doi: 10.1111/liv.12456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobrosotskaya IY, Seegmiller AC, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Rawson RB. Regulation of SREBP processing and membrane lipid production by phospholipids in Drosophila. Science. 2002;296:879–883. doi: 10.1126/science.1071124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan KK, Tremaroli V, Clemmensen C, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Myronovych A, Karns R, et al. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature. 2014;509:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature13135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang S, Suh JM, Reilly SM, Yu E, Osborn O, Lackey D, et al. Intestinal FXR agonism promotes adipose tissue browning and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2015;21:159–165. doi: 10.1038/nm.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]