Abstract

Background

Increased legalization of marijuana has resulted in renewed interest in its effects on body weight and cardiometabolic risk. Conflicting data exist regarding marijuana effects on body weight, waist circumference as well as lipid profiles, blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, there is a dearth of data available on this effect in the black population.

Objective

To assess the metabolic profile and cardiovascular risk factors as well as body weight and waist circumference among urban black marijuana users.

Methods

A cross sectional study design involving 100 patients seen in a Family Practice clinic at University hospital of Brooklyn, NY, USA, over a period of 3 months from January 2014 to March 2014. Participants were administered a questionnaire regarding marijuana use, and other associated behaviors. Socio-demographic, laboratory, and clinical data were collected. We report measures of central tendencies, and dispersion for continuous variables and the frequency of distribution for categorical variables.

Results

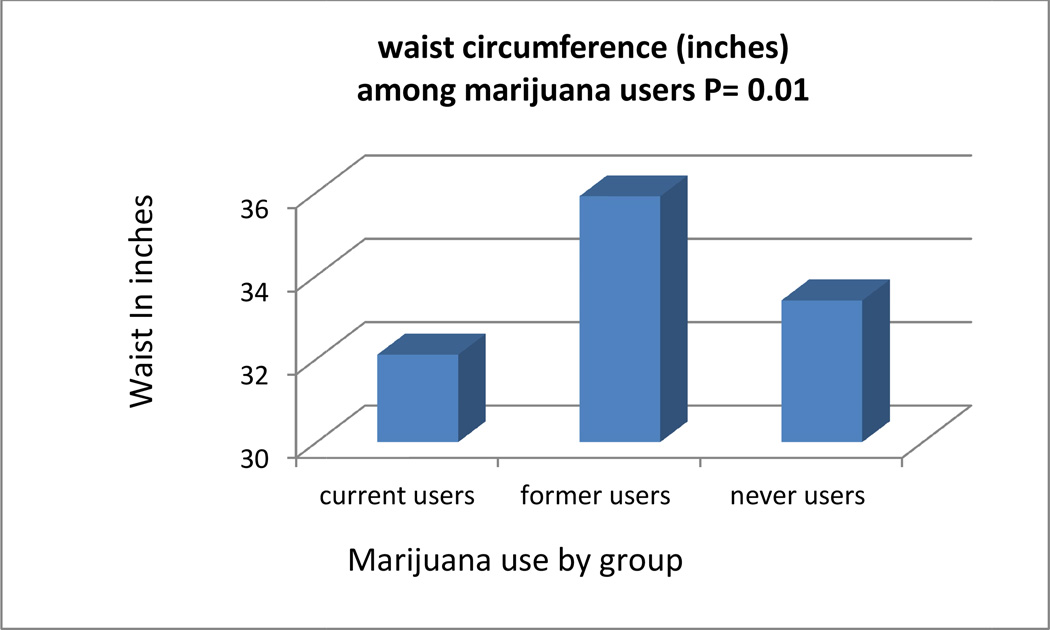

Of the 100 patients surveyed, 57% were females. The mean (±SEM) age of the entire cohort was 46.3 years±1.5; range, 19–78 years. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 29.6 kg/m2±0.73; SBP=128.0 mmHg±1.69; DBP=76.1 mmHg±1.17. Current marijuana users had the lowest waist circumference compared to former or never users respectively (32.9±0.66 vs. 35.9±0.88 vs. 33.4±0.74), p<0.01. Diastolic blood pressure in mmHg was significantly higher among former marijuana users compared to current or never users, (80.0±2.1 vs. 73.3±2.3 vs. 73.4±1.6), p<0.01.

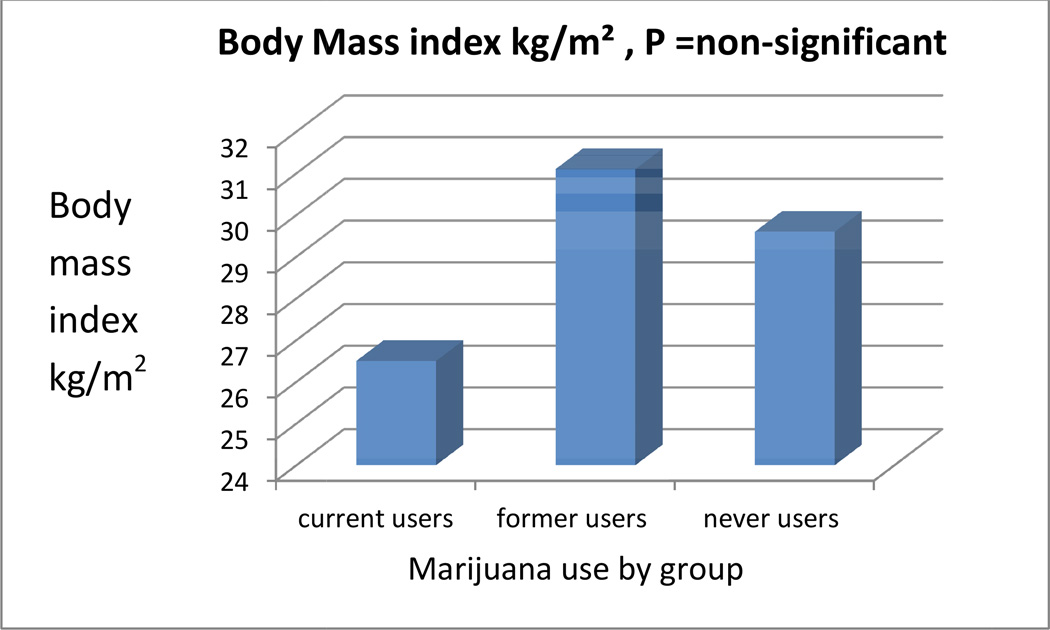

Current marijuana users showed a tendency (not statistically significant) towards lower total cholesterol, Triglycerides (TG), High Density Lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, body mass index (BMI) and systolic blood pressure, compared to former users or never users.

Conclusion

Current marijuana use is associated with significantly lower waist circumference, compared to former users and never users. Except for diastolic BP that was significantly lower among current users, other metabolic parameters showed tendency towards favorable profile. Further studies are needed to characterize the metabolic effects and to elucidate mechanisms of actions of marijuana in view of its rapid rate of utilization in the USA and around the world.

Keywords: Marijuana, metabolic risk factors, body weight, black population

1. INTRODUCTION

Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal substance worldwide [1]. At least 160 million people or approximately 4.0% of the world’s population between the ages of 15 and 64 years have been estimated to use cannabis at least once in the past year [2,3]. Emerging data from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health showed that adults older than 26 years reported marijuana use as the most frequently used drug, with a 5.6% current marijuana use rate [3]. Nearly twenty million individuals (aged 12 years old and above) used marijuana within the past month. Changes among adults aged 50 years and older show that the highest increase in reported current marijuana use was among 55–59 year olds [4]. However, recent trend of legalizing marijuana is likely to have a larger impact on the pattern of use and makes the questions about the metabolic effects of cannabinoids timely and highly topical. Currently, besides the District of Columbia, 23 states have legalized marijuana use in some form. There are four states that have legalized marijuana for recreational use with 2 more states- Alaska, and Oregon that will be added to the rapidly growing list in 2015 [5]. Besides decriminalization and increased legalization, the marked increase of marijuana use particularly among adolescents is contributed to by other factors such as the lack of perception of harm. In fact data indicate that the perceived risk of marijuana use is at its lowest level [3,4,6].

Marijuana is associated with an acute increase in appetite and high caloric intake. For example, in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study [7], using 15 years of longitudinal data from 3,617 participants with 1,365 reporting the use of marijuana, the more extensive use was associated with higher caloric intake. Interestingly, in this study, despite increased caloric intake, there was no increase in BMI, lipid or glucose values [7]. Furthermore, the increased caloric intake was largely attributed in this study to the associated increase in alcohol consumption [7]. Increased caloric intake was largely thought to be mediated through cannabinoid receptors type 1 (CB1) [8]. These findings led to the development of Rimonabant, a selective blocker of the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) for the treatment of multiple cardiometabolic risk factors, including abdominal obesity [9].

In the United States, some medications containing delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are approved by the Food and Drug administration (FDA) for treating chemotherapy and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-induced anorexia and nausea [10]. The higher caloric intake among marijuana users, compared to non-users, was also demonstrated in other studies [2,10,11].

While some data suggest marijuana use to confer cardiometabolic benefits such as reductions in Lower Density Lipoprotein (LDL), fasting insulin, glucose, and hemoglobin A1C levels [2], Other studies show that marijuana users have a lower adipocyte insulin resistance index, lower plasma High Density Lipoprotein (HDL), and higher percent abdominal visceral fat, which are important risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease [11,12].

Therefore, although marijuana is a frequently abused drug, its lasting effects on cardiovascular risk factors are not clear. Given the paucity of data on metabolic significance of marijuana use, particularly among the black population, the objective of the study was to investigate the potential effects of marijuana on metabolic risk factors and body weight among black patients.

2. METHODS

Approval for this study was obtained from the State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Hospital Institutional Review Board. The participants signed informed consent. In a cross sectional study design involving consecutive case series of 100 black patients, at a Family Practice clinic at University Hospital of Brooklyn, NY, USA, over a period of 3 months from January 2014 to March 2014, a standardized questionnaire regarding marijuana use and other associated behaviors adopted from previous study by Penner EA et al. [2], was administered to each patient, who was willing and able to sign an informed consent during the clinic visit. Socio-demographic (age, sex and race), laboratory, as well as clinical data such as blood pressure, weight, BMI, waist circumference, presence of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia were collected.

Laboratory values were extracted from medical records and done within the past 3 months; they included total cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), LDL and HDL cholesterol, blood glucose, and hemoglobin A1C.

In addition, information on lifestyle behavior (physical activity, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug as well as marijuana use history) was collected.

Survey participants (SPs) answered “Yes” or “No” to the question “Have you ever, even once, used hashish / marijuana?” Former and current marijuana users were determined by the question “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?” with answers given as a numerical value in days, months or years. Frequency of marijuana consumption was assessed by asking the SPs “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use marijuana or hashish?” Marijuana users who had smoked the drug within the last 180 days were categorized as current users, while individuals who had use marijuana at least once but not in the last 180 days were considered former users. And individuals who had not smoked marijuana at all were classified as never users.

Frequencies, proportions, means, and SDs were used to describe the overall sample, and the marijuana users and non-users. Student’s t-test and chi-square tests were used to compare the descriptive statistics depending on data type. Data was analyzed using SPSS statistical package version 21 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL).

3. RESULTS

Of the 100 patients surveyed, 57% were females. The mean (±SEM) age of the entire cohort was 46.3 years ± 1.5; range, 19–78 years. The mean body mass index (BMI) 29.6 kg/m 2±0.73; SBP=128.0 mmHg±1.69; DBP=76.1 mmHg ± 1.17 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolic clinical characteristics of study participants

| Mean | Std error | |

|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 181.3 | 4.96 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 119.3 | 8.03 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103.3 | 4.46 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 54.9 | 2.69 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 111.0 | 4.88 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 6.57 | 0.27 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 29.6 | 0.73 |

| Waist circumference (inches) | 34.2 | 0.54 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 128.0 | 1.69 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 76.1 | 1.17 |

| Clinical features | ||

| Age | 46.3 | 1.53 |

| Female (%) | 57 | |

| Hypertension (%) | 47 | |

| Diabetes (%) | 22 | |

| Hypertension and Diabetes (%) | 14 | |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 22 | |

| Coronary Heart disease (%) | 11 | |

| Current smoking (%) | 22 | |

| Former cigarette smokers (%) | 49 | |

| Alcohol consumption over the past 3 months (%) | 44 | |

| Current drug abuse (%) | 18% | |

LDL = low density lipoprotein, HDL = high density lipoprotein, BMI = body mass index (kg/m2)

Dyslipidemia was reported in 22% of the cohort, 11% had coronary heart disease, 22% were current cigarette smokers, 49% were ex- smokers and 18% were current drug users. Alcohol consumed over the past 3 months was reported in 44% of the cohort.

Twenty-two percent of the study cohort had diabetes, 47% had hypertension; while 14% suffered both diabetes and hypertension. About 61% of the cohort reported smoking marijuana at least once, of whom 41% quit in the past 6 months, and 15% are current smokers.

Patients who have not smoked marijuana in the past 6 months (former users) had a significantly higher waist circumference in inches than current users or never users respectively (35.9±0.88 vs. 32.9±0.66 vs. 33.4±0.74), p<0.01; as well as significantly greater diastolic blood pressure in mmHg (80.0±2.1 vs. 73.3±2.3 vs. 73.4±1.6), p<0.01 (Table 2). In addition, former marijuana users had higher cholesterol levels in mg/dL (189.0±8.10) than current (156.9±9.42) and never users (181.8±6.97), this was marginally non-significant, p<0.0569. There was no significant difference in the levels of HDL in mg/dL (57.6±5.05 vs. 48.3±3.65 vs. 54.6±3.90), p=NS; LDL in mg/dL (105.9±7.92 vs. 92.5±7.75 vs. 103.8±6.64), p=NS; BMI in Kg/m2 (31.1±1.17 vs. 26.5±2.06 vs. 29.6±1.00), p=NS; and triglyceride in mg/dL (133.0±15.0 vs. 85.9±9.58 vs. 120.3±12.3), p=NS; among former, current and never users of marijuana; respectively.

Table 2.

Comparison of metabolic markers between current users, former users and never users

| Current users |

(±SEM) | Former users |

(±SEM) | Never users | (±SEM) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 156.9 | 9.42 | 189.0 | 8.10 | 181.8 | 6.97 | 0.0569 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 85.9 | 9.58 | 133.0 | 15.00 | 120.3 | 12.30 | 0.1245 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 92.5 | 7.75 | 105.9 | 7.92 | 103.8 | 6.64 | 0.5527 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 48.3 | 3.65 | 57.6 | 5.05 | 54.6 | 3.90 | 0.4737 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 108.7 | 13.27 | 108.7 | 6.82 | 112.6 | 8.39 | 0.9287 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 7.2 | 1.13 | 6.4 | 0.39 | 6.5 | 0.30 | 0.6252 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26.5 | 2.06 | 31.1 | 1.17 | 29.6 | 1.00 | 0.0906 |

| Waist circumference (inches) | 32.1 | 1.35 | 35.9 | 0.88 | 33.4 | 0.74 | 0.0175 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 126.0 | 4.40 | 129.5 | 2.52 | 127.7 | 2.79 | 0.7593 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 73.3 | 2.25 | 80.0 | 2.13 | 73.4 | 1.58 | 0.0245 |

LDL = low density lipoprotein, HDL = high density lipoprotein, BMI = body mass index (kg/m2)

Between the patients who had used marijuana at least once in their lifetime and non- users, there were no significant differences in any of the metabolic parameters examined (Table 3). The proportion of patients with diabetes was not significantly different among marijuana users and non-users, 26.7% versus 20.3%, P=0.57 for users and non-users respectively. There was also no significant difference in the mean ages of current, former, and never users, or the frequency of marijuana users by sex.

Table 3.

Metabolic markers in marijuana users and non-users

| Marijuana user | Marijuana non-user | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std error | Mean | Std error | ||

| Cholesterol | 181.1 | 6.93 | 181.8 | 6.97 | 0.9529 |

| Triglycerides | 118.5 | 10.8 | 120.3 | 12.3 | 0.9186 |

| LDL-cholesterol | 102.9 | 6.09 | 103.8 | 6.64 | 0.9294 |

| HDL-cholesterol | 55.3 | 3.71 | 54.6 | 3.90 | 0.8956 |

| Glucose | 108.9 | 6.00 | 112.6 | 8.39 | 0.7093 |

| HbA1C | 6.6 | 0.40 | 6.5 | 0.30 | 0.8176 |

| BMI | 29.6 | 1.03 | 29.6 | 1.00 | 0.9745 |

| Waist circumference (inches) | 34.6 | 0.74 | 33.4 | 0.74 | 0.2692 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 128.0 | 2.16 | 127.7 | 2.79 | 0.9330 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 77.9 | 1.62 | 73.4 | 1.58 | 0.0673 |

LDL = low density lipoprotein, HDL = high density lipoprotein, BMI = body mass index (kg/m2)

4. DISCUSSION

Our study showed that current marijuana users have significantly smaller waist circumferences compared to former users, or non-users (Table 1, Fig. 1). There was also tendency towards a lower BMI among current marijuana users, however, that did not reach statistical significance, likely due to the small sample size. These findings are quite important given the current epidemic of obesity and its attendant cardiovascular risk and the fact that waist circumference is an important predictor for cardiovascular risk, more so than BMI itself [12–15]. However, in our study we are unable to ascertain if the significantly lower waist circumference is due to a decrease in subcutaneous fat or intra-abdominal fat content. This is quite important since the increased cardiovascular risk associated with abdominal obesity is largely attributed to visceral fat [16–18]. To illustrate this point, a recent study that is well-conducted, at the National Institute of Health by Muniyappa et al. [11] on the metabolic effects of chronic cannabis smoking showed that chronic marijuana use, compared to control, is associated with visceral adiposity and insulin resistance in the adipose tissue [11]. This study is quite relevant to ours for enrolling a large percentage of blacks (73%) and it showed no association of cannabinoid use on total cholesterol, LDL- cholesterol, fasting glucose level or triglycerides [11]; data that is consistent with that shown here by our group (Table 1). Furthermore, our study also assessed hemoglobin A1c which is a surrogate measure of chronic (2–3 months) glucose control and there was no difference in A1c between the users and non-users of marijuana (Tables 1, 2). Interestingly, data from Muniyappa group [11] also showed lower HDL-cholesterol among marijuana users compared to non-users (49±14 versus 55±13 mg/dl, P= 0.02), our data showed a trend towards lower HDL- cholesterol among users of marijuana compared to former users or never users, however the difference did not reach statistical significance, again likely due to a small sample size (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of marijuana use on waist circumference in inches. Current users have significantly lower waist circumference

Our data is also consistent with a large study by Penner et al. [2] that included 4,657 adult men and women from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted between 2005 to 2010. In this study, Current marijuana use was significantly associated with smaller waist circumferences. However there was no significant dose-response identified [2]. Consistent with our study also, this large data set showed no differences among current, past, or never used marijuana groups in the cardiovascular parameters including systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, or HDL-cholesterol levels.

In contrast to our study, however, there was statistically significant lower hemoglobin A1C among current marijuana users compared to past users or never users (5.4% versus 5.4% versus 5.5%, P 0.3), for current, past and never marijuana users respectively [2]. This difference however is minimal and clinically insignificant and likely influenced by the large sample size of the study that also showed significantly lower BMI among current marijuana users [2], a finding that our study also demonstrated but it did not reach statistical significance (Table 2 Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of marijuana use on body mass index kg/m2. Current users had lower BMI, compared to former users or never users, results did not reach statistical significance but showed a trend P = 0.09

It is important, however to note that in contrast to our data which involves mainly a Black population, NHANES data set used by Penner et al. Contained, only 20% blacks with the majority (44%) of the population being Caucasians and 30% Hispanics [2].

Another study from the NHANES III, 1988–1994 data set conducted at the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention by Rajavashisth et al. [19] with 10,896 adult US population showed significantly lower odds of DM among marijuana users (adjusted OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.55; p<0.0001) [19]. This is in contrast to our study where we found no difference in diabetes rate among current, past, and never marijuana users. It is important to note that Rajavashisth et al. [19] concluded that a causal relationship could not be established and recommended against the use of marijuana to prevent diabetes.

Finally, it is important also to note that highest waist circumference in our study was observed among former marijuana users compared to current and never users (35.9 versus 32.1 versus 33.4 (inches), P 0.017) for former, current, and never users respectively. Former marijuana users also tended to have higher BMI, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and triglycerides; none of these metabolic parameters however reached statistical significance although certainly demonstrated a trend for unfavorable cardiometabolic profile among marijuana quitters. Therefore, our study suggests that marijuana quitting is associated with deleterious effects on waist circumference, weight, and other metabolic parameters that are consistent with the plethora of data on weight gain and other cardiovascular risk factors after cessation of cigarette smoking [20–24]; findings that are still of undetermined significance on cardiovascular outcomes compared to the effects of continued smoking that is certainly harmful [24].

5. CONCLUSION

Our study on the cardio-metabolic effects on marijuana use among black population from an inner city institution showed consistent results on the association of marijuana use with lower waist circumference that has been demonstrated previously among populations that are largely white. Our study is also consistent with data showing lack of cardio-metabolic benefits of marijuana use, as in the landmark Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study where no beneficial effects of marijuana use were demonstrated.

Finally, while lower waist circumference has beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk, in the context of marijuana use this benefit is uncertain since the lower waist circumference appears to be primarily due to subcutaneous fat decrease as opposed to abdominal visceral fat which was actually higher in percentage among chronic marijuana users in a recently published study. Therefore, until further research is performed to determine the effects of marijuana on hard endpoints such as coronary artery disease, we do not recommend marijuana use for cardio-metabolic benefits; we also do not recommend cannabis for diabetes prevention or weight loss, given the uncertain and largely conflicting data shown in various studies.

5.1 Strength / Limitations

Our study adds to the growing literature on the value of marijuana in controlling metabolic syndrome. Consecutive family clinic patients were included in this series, thus limiting any selection bias because all patients who attended the clinic were offered the study questionnaire instrument to be part of the study.

Limitations of the study include the small sample size. Another important limitation relates to the fact that marijuana use was based on self-reported data and therefore subject to under-estimation or denial of illicit drug use. The study was performed at an inner city family medicine clinic, and the results are not generalizable to other communities. Future studies should examine whether other metabolic parameters such as LDL, HDL, glucose, hemoglobin A1c, BMI, or SBP would show significant effects in a larger sample size.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was supported by funding from Health Science Center of Brooklyn (HSCB) Foundation Incorporated. It was also supported in-part by funding from the National Institutes of Health: R25HL105444, R01HL095799, R01MD004113, and U54NS081765. The funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. All authors intellectually contributed to the design, analysis and interpretation of the results and to drafting the critical review of manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Institutional Review Board approval confirms that the study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

POTENTIAL COMPETING INTEREST / DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have read the journal’s policy and declare that they have no proprietary, financial, professional, nor any other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product or services and / or company that could be construed or considered to be a potential conflict of interest that might have influenced the views expressed in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leggett T. United Nations Office on D, Crime. A review of the world cannabis situation. Bull Narc. 2006;58(1–2):1–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penner EA, Buettner H, Mittleman MA. The impact of marijuana use on glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance among US adults. Am J Med. 2013;126(7):583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockville MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Accessed on Jan 13, 2015]. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. Available: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vidot DC, Prado G, Hlaing WM, Arheart KL, Messiah SE. Emerging issues for our nation's health: the intersection of marijuana use and cardiometabolic disease risk. J Addict Dis. 2014;33(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2014.882718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.State Marijuana Laws Map. [Accessed on January 13, 2015]; Available: http://www.governing.com/gov-data/state-marijuana-laws-map-medical-recreational.html.

- 6.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Humphrey RH. Explaining the recent decline in marijuana use: Differentiating the effects of perceived risks, disapproval and general lifestyle factors. J Health Soc Behav. 1988;29(1):92–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodondi N, Pletcher MJ, Liu K, Hulley SB, Sidney S. Coronary artery risk development in young adults S. Marijuana use, diet, body mass index, and cardiovascular risk factors (from the CARDIA study) Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(4):478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickers SP, Kennett GA. Cannabinoids and the regulation of ingestive behaviour. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6(2):215–223. doi: 10.2174/1389450053174514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelfand EV, Cannon CP. Rimonabant: A cannabinoid receptor type 1 blocker for management of multiple cardiometabolic risk factors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(10):1919–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Drug Administration. Label and approval history: marinol. [Accessed on January 13, 2015]; Available: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseactionSearch.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist.

- 11.Muniyappa R, Sable S, Ouwerkerk R, Mari A, Gharib AM, Walter M, et al. Metabolic effects of chronic cannabis smoking. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2415–2422. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFarlane SI, Banerji M, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):713–718. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pataky Z, Bobbioni-Harsch E, Makoundou V, Golay A. Enlarged waist circumference and cardiovascular risk factors. Rev Med Suisse. 2009;5(196):671–672. 4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castro JP, El-Atat FA, McFarlane SI, Aneja A, Sowers JR. Cardiometabolic syndrome: pathophysiology and treatment. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2003;5(5):393–401. doi: 10.1007/s11906-003-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karam JG, El-Sayegh S, Nessim F, Farag A, McFarlane SI. Medical management of obesity: an update. Minerva Endocrinol. 2007;32(3):185–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamdy O, Porramatikul S, Al-Ozairi E. Metabolic obesity: The paradox between visceral and subcutaneous fat. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2006;2(4):367–373. doi: 10.2174/1573399810602040367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermsdorff HH, Monteiro JB. Visceral, subcutaneous or intramuscular fat: Where is the problem? Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2004;48(6):803–811. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302004000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith SR, Lovejoy JC, Greenway F, Ryan D, deJonge L, de la Bretonne J, et al. Contributions of total body fat, abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments and visceral adipose tissue to the metabolic complications of obesity. Metabolism. 2001;50(4):425–435. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.21693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajavashisth TB, Shaheen M, Norris KC, Pan D, Sinha SK, Ortega J, et al. Decreased prevalence of diabetes in marijuana users: Cross-sectional data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000494. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Issa JS, Santos PC, Vieira LP, Abe TO, Kuperszmidt CS, Nakasato M, et al. Smoking cessation and weight gain in patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factor. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172(2):485–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komiyama M, Wada H, Ura S, Yamakage H, Satoh-Asahara N, Shimatsu A, et al. Analysis of factors that determine weight gain during smoking cessation therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lecerf JM. Smoking cessation and weight gain. From one addiction to another? Soins. 2014;783(Suppl 2):2S11–2S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seignol L, Bas CN. Smoking cessation and prevention of weight gain. Rev Infirm. 2013;196:49–50. doi: 10.1016/j.revinf.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tonstad S. Weight gain does not attenuate cardiovascular benefits of smoking cessation. Evid Based Med. 2014;19(1):25. doi: 10.1136/eb-2013-101350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]