Abstract

Background and Purpose

Ischaemic stroke is a serious disease with limited therapy options. Glycoprotein (GP)Ib binding to von Willebrand factor (vWF) exposed at vascular injury initiates platelet adhesion and contributes to platelet aggregation. GPIb has been suggested as an effective target for antithrombotic therapy in stroke. Anfibatide is a GPIb antagonist derived from snake venom and we investigated its protective effect on experimental brain ischaemia in mice.

Experimental Approach

Focal cerebral ischaemia was induced by 90 min of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). These mice were then treated with anfibatide (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1), injected i.v., after 90 min of MCAO, followed by 1 h of reperfusion. Tirofiban, a GPIIb/IIIα antagonist, was used as a positive control.

Key Results

Twenty-four hours after MCAO, anfibatide-treated mice showed significantly improved ischaemic lesions in a dose-dependent manner. The mice had smaller infarct volumes, less severe neurological deficits and histopathology of cerebrum tissues compared with the untreated MCAO mice. Moreover, anfibatide decreased the amount of GPIbα, vWF and accumulation of fibrin(ogen) in the vasculature of the ischaemic hemisphere. Tirofiban had similar effects on infarct size and fibrin(ogen) deposition compared with the MCAO group. Importantly, the anfibatide-treated mice showed a lower incidence of intracerebral haemorrhage and shorter tail bleeding time compared with the tirofiban-treated mice.

Conclusions and Implications

Our data indicate anfibatide is a safe GPIb antagonist that exerts a protective effect on cerebral ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Anfibatide is a promising candidate that could be beneficial for the treatment of ischaemic stroke.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic receptorsa | Enzymesb | |

| GPIb | IL-4 receptor α | ADAMTS13 |

| GPIIb | Mac-1 |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| Fibrinogen |

| Tirofiban |

| Von Willebrand factor |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,bAlexander et al., 2013a,b).

Introduction

Ischaemic stroke is a leading cause of death and disability. Approximately 80% of strokes are caused by focal cerebral ischaemia due to arterial occlusion. A key cause of cerebral ischaemia is platelet-derived thrombus formation at the site of the damaged endothelium. Thromboembolic occlusion of major or multiple smaller intracerebral arteries leads to focal impairment of the downstream blood flow, and to secondary thrombus formation within the cerebral microvasculature (Stoll et al., 2008). Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapies have been demonstrated to be effective in patients with acute stroke. Thrombolytic therapy re-establishes tissue perfusion in order to reduce neurological deficits and improve functional outcome. However, less than 10% of patients qualify for this treatment due to the limited time window, 3.0–4.5 h after symptom onset, and the risk of severe intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH) with later treatments (Adams et al., 2003; Hacke et al., 2008; Fisher, 2011).

Because platelet adhesion is the initial step in the pathogenesis of thrombosis, the use of platelet adhesion inhibitors may be a useful therapeutic intervention to effectively prevent the formation of blood clots. The treatment strategy, which inhibits platelet activation by blocking platelet membrane glycoprotein (GP)IIb/IIIα to prevent platelet aggregation has been used for many years, but excessive GPIIb/IIIα blockade is inevitably associated with major bleeding complications in mice and reflects similar findings in acute stroke patients, so it cannot be recommended at present (Adams et al., 2008; Stoll et al., 2008; Kellert et al., 2013). A more effective treatment may include targeting platelet adhesion and upstream signalling pathways.

The initial step for attracting platelets to sites of vascular injury is mediated by GPIb-V-IX, a structural receptor complex exclusively expressed in platelets and megakaryocytes. The GPIb-V-IX complex is formed by four distinct transmembrane proteins: GPIbα, GPIbβ, GPV and GPIX. GPIbα is the major ligand-binding subunit of the GP complex, which binds von Willebrand factor (vWF), and initiates platelet adhesion in haemostasis and thrombosis (Berndt and Andrews, 2002; Andrews and Berndt, 2004; Varga-Szabo et al., 2008; Mu et al., 2010). GPIbα is required for platelet adhesion under conditions of high shear such as in the cerebrovascular arterial system. Inhibition of GPIb with Fab fragments of the monoclonal antibody p0p/B blocked platelet adhesion and aggregation in a model of mechanically induced thrombosis formation as well as in ischaemic stroke (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007).

GPIb has long been suggested as an effective target for inhibition of platelet adhesion in antithrombotic therapy (Stoll et al., 2008; 2010,), but anti-GPIb agent for therapy has shortly been developed. Anfibatide (trade name of agkisacucetin) is a GPIb antagonist, a C-type lectin-like protein derived from the protein complex agglucetin. It has a typical snaclec structure of a heterodimer with two closely related subunits: α and β chains (Lei et al., 2014). Earlier study has demonstrated that each anfibatide αβ-heterodimer molecule binds to one GPIbα molecule and inhibits GPIbα–vWF interaction by blocking the access of vWF to GPIbα without causing GPIb clustering (Gao et al., 2012). In this study, we examined the protective effect of a GPIb antagonist on experimental stroke using anfibatide, administered i.v. after 90 min of cerebral ischaemia followed by 1 h reperfusion in mice. Together with previous findings (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007), our study suggests that blockade of the GPIb signalling pathway, a key event required for platelet adhesion and thrombus formation, may provide a promising treatment strategy for ischaemic stroke.

Methods

Experimental animals

Pharmacological experiments were performed using healthy Kunming mice (6- to 8-week-old male mice at 26–28 g body weight, SPF) purchased from the Animal Centre Laboratory (Anhui Medical University, China). Mice were housed at 22°C with a relative humidity of 60 ± 5% and on a 12 h light/dark cycle, with free access to food and water and were allowed at least 3 days to acclimatize before experimentation. The total number of mice used in our experiments was 336. All mice were separated into a sham-operated group and middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) group. The latter was further randomly separated into a MCAO-only group, anfibatide (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1) and tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) groups. All experimental protocols described in this study were approved by the regulations stipulated by Anhui Medical University Animal Care Committee following the protocol outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

MCAO model

The MCAO model was used to induce focal cerebral ischaemia (Clark et al., 1997). Mice were anaesthetized with chloral hydrate (0.35 g·kg−1) by i.p. injection. Transient right MCAO was induced by inserting a nylon thread with standardized diameter (0.148–0.165 mm) to an appropriate depth (9–11 mm) determined by the animal’s body weight. The tip of the nylon thread was rounded by paraffin to block the origin of the middle cerebral artery. After 90 min, the occluding nylon thread was removed to allow reperfusion. The body temperature was maintained at 37°C throughout surgery. Sham-operated mice underwent the same surgical procedure except that their origin of the middle cerebral artery was not occluded. All animals were operated on by the same person in the same conditions to reduce infarct variability, and operation time per animal did not exceed 15 min.

Immediately following MCAO, mice were randomly divided into MCAO-only group, anfibatide (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1) and tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) treatment groups. The sham-operated and MCAO-only groups received saline injections. The anfibatide and tirofiban groups were treated with the respective drugs, injected i.v., after 90 min of cerebral ischaemia followed by 1 h reperfusion. After recovery from anaesthesia and again after 24 h of reperfusion, global neurological status and coordination were evaluated according to the method of Bederson score and foot fault test.

Platelet counts

Mice, not subjected to MCAO, were randomly assigned to five groups including control group, anfibatide (1, 2, 4 μg·kg−1) and tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) groups. Mice received drugs or normal saline by i.v. injection. One hour later, mice were anaesthetized with chloral hydrate (0.35 g·kg−1, i.p. injection), and blood was collected via a retro-orbital puncture to measure platelet counts (De Meyer et al., 2011; Sharma et al., 2014). A sterile capillary pipette was cut to appropriate length, and the cut ends were ground to have flat edges. The eyelid was gently pulled back from the eyeball. The capillary pipette was placed at the lateral canthus and was oriented towards the back of the head at an angle of 45° to the sagittal and coronal planes. It was gently turned with pressure against the orbital bone just in front of the zygomatic arch until blood flowed from capillaries that drained the orbital sinus into the superficial temporal vein. The capillary pipette was pulled back and blood was collected into EDTA-K2-containing collection tube by capillary action. Care was taken to ensure adequate haemostasis following the procedure. Platelet counts in whole blood were determined using a Sysmex pocH-100iV Diff Hematology analyser (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan).

Measurement of cerebral infarct volumes

Cerebral infarct volumes were evaluated at 24 h after reperfusion in mice subjected to 90 min of MCAO. Mice were decapitated and the brains were rapidly removed. Five serial sections from each brain were cut at 2 mm intervals. To measure ischaemic volumes, brain slices were stained in 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) (Sigma T8877, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. TTC-stained brain slices were transferred to 10% neutral-buffered formaldehyde. Areas of infarction were visualized as regions lacking the typical brick red staining of normal brain tissue. These areas were photographed and quantified with ImageJ image processing software (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (Suzuki et al., 2012; Espinera et al., 2013).

Bederson score measurement

Twenty-four hours after MCAO, neurological deficits of mice were assessed and scored in a blinded fashion using a modification of the Bederson neurological scale (Bederson et al., 1986; Kawano et al., 2006; Abe et al., 2009). Neurological scores were recorded as follows: 0, no neurological deficit; 1, failure to fully extend left forepaw or flexion of torso and contralateral forelimb when mouse was lifted by the tail; 2, reduced resistance to lateral push or circling to the contralateral side when mouse was held by the tail on a flat surface, but normal posture at rest; 3, spontaneous circling to left; 4, absence of spontaneous movement or unconsciousness.

Foot fault test

Twenty-four hours after MCAO, mice were tested for placement dysfunctions of forelimbs with the modified foot fault test (Hernandez and Schallert, 1988; Liu et al., 2013). They were placed on an elevated grid floor, with 1.5 × 1.5 cm diameter openings. The total number of steps used to cross the grid and the total numbers of foot faults for each forelimb were recorded. The percentages of foot faults to the total number of steps were calculated.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical staining of cerebral tissues

Twenty-four hours after MCAO, all mice were anaesthetized with chloral hydrate (0.35 g·kg−1), and perfused with ice-cold saline and 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin (pH 7.1) for 72 h before being dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned (4 μm) with a cryostat slicer. For conventional morphological evaluation, the paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized, hydrated, washed and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

For fibrin(ogen) detection, the paraffin-embedded brain coronal sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated, heated in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and cooled in deionized water. Sections were immersed in methanol containing 3% H2O2 at 37°C for 30 min to quench endogenous peroxidase, then incubated with polyclonal goat anti-fibrinogen β antibody (Santa Cruz, 1:100; Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C, then washed with PBS, and incubated with polymer helper at 37°C for 20 min, followed by poly peroxidase-anti-goat IgG at 37°C for 25 min, and visualized using diaminobenzidine method. Immunoreactive vessels were stained brown and images were captured under the microscope.

Protein extraction and Western blot for fibrin(ogen)

Twenty-four hours after MCAO, mice were killed and the brains were removed. The cortices of ipsilateral hemispheres were homogenized in RIPA buffer using tissue grinder on ice for 30 min. Then, tissue lysates were centrifuged at 10 000× g for 15 min at 4°C and the total protein concentrations were assessed with BCA protein assay kit. The total supernatants were treated with SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer at 100°C for 10 min. Thirty micrograms of total protein was electrophoresed and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Then the membranes were incubated in blocking buffer [5% non-fat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween (TBS-T)] for 2 h to reduce non-specific binding. The membranes were incubated with the primary antibody [goat anti-fibrin(ogen) β, 1:300 in TBS-T; mouse monoclonal anti-actin, 1:1000 in TBS-T] at 4°C overnight, washed with TBS-T, incubated for 2 h with HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG [for fibrin(ogen), 1: 6000] or rabbit anti-mouse IgG (for actin, 1:10 000) and were detected using ECL plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Blot bands were quantified using the densitometry method (ImageJ).

Immunofluorescence staining

To detect the expression of vWF and GPIbα in the ischaemic cerebral microvessels, double immunofluorescent staining was performed. Twenty-four hours after MCAO, mice were anaesthetized with chloral hydrate (0.35 g·kg−1) and transcardially perfused with ice-cold saline and 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and then post-fixed for 24 h in the same fixative. The post-fixed brain tissues were cryoprotected in 20% then 30% sucrose in PBS. Brains were serially sectioned (10 μm). The brain cryosections were air dried, rinsed in PBS and incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min. After non-specific blocking in normal donkey sera, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in the following primary antibodies: monoclonal mouse anti-vWF (Santa Cruz, 1:100), polyclonal goat anti-platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) (Santa Cruz, 1:100) and polyclonal rabbit anti-GPIbα (Biorbyt, 1:100, Cambridge, UK). Sections were incubated with the appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antisera [donkey anti-mouse IgG-PE (Santa Cruz), donkey anti-goat IgG-FITC (Santa Cruz), donkey anti-rabbit IgG-PE (Santa Cruz)] used at 1:100 dilutions for 1 h. From this point forward, sections were protected from light. Sections were counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime, 1:400, Shanghai, China) and coverslipped with anti-fading mounting medium. Negative controls were conducted by staining sections as described earlier, but with the use of PBS instead of the primary antibodies, no detectable labelling was observed. Immunofluorescence images were captured using a Laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica, Frankfurt, Germany). The mean densities of vWF and GPIbα were used to quantify their expressions by the Image-Pro plus 6.0 analysis system (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA), in corresponding sections of five mice in each group.

Spectrophotometric assay of ICH

Cerebral haemorrhage was quantified by using a spectrophotometric assay for haemoglobin (Sumii et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2004). A standard curve was generated by blending normal brain samples with different volumes of mouse blood. Incremental volumes of homologous blood (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 50, 100, 200 μL) were added to each hemispheric sample with PBS to reach the volume of 3 mL, followed by homogenization for 30 s, sonication for 1 min and centrifugation at 10 000× g for 30 min. Drabkin’s reagent (240 μL, Sigma) was added to 60 μL of aliquots and allowed to stand for 15 min. Optical density was measured at 540 nm with a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax 190, Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). A linear relationship between haemoglobin concentrations in perfused brain and blood volume was yielded. Twenty-four hours after MCAO, haemorrhage volume was expressed in equivalent units by comparison with a reference curve generated as above.

The occurrence of ICH was assessed on five coronal brain slices before and after TTC staining in mice. Images of TTC-stained sections were captured and analysed using ImageJ.

Assessment of tail vein bleeding time

Tail bleeding time was determined in mice that were not subjected to stroke (Sugidachi et al., 2000; Lei et al., 2014). Mice were randomly assigned to five groups including control group, anfibatide (1, 2, 4 μg·kg−1) and tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) groups. Drugs were i.v. administered 30 min before the tail transection. Under anaesthesia with chloral hydrate (0.35 g·kg−1, i.p. injection), a 3 mm segment of the tail tip was amputated and the tail was immersed into saline (37°C) to bleed. Time was recorded from the moment blood was observed to emerge from the wound until cessation of blood flow.

We also assessed the bleeding time at 24 h after MCAO. Following MCAO, mice were randomly divided into a control MCAO group, anfibatide (1, 2, 4 μg·kg−1) and tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) groups. Sham and MCAO groups received saline injections. After 24 h of reperfusion, bleeding time was evaluated according to the method described earlier.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Comparisons of multiple groups were performed using one-way anova with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. The rates of ICH 24 h after MCAO were compared between groups with χ2 test. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reagents

Anfibatide was provided by Zhaoke Pharmaceutical Company Limited (Hefei, Anhui, China), batch number 20120420. Anfibatide was purified by anion exchange and monoclonal antibody-based affinity chromatography followed by Sephacryl S-100 column. After purification, anfibatide was analysed by MALDI-TOF-MS (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry) and only one peak appeared indicating its purity, and the mass to charge ratio was 29 799.7 (Lei et al., 2014). Tirofiban is a non-peptide platelet GPIIb/IIIα receptor reversible antagonist provided by Grand Company Limited (Wuhan, China), ratify number H20041165.

Nomenclature

Nomenclatures of receptors conform to BJP’s Concise Guide to Pharmacology (Alexander et al., 2013,).

Results

Effect of ANF on platelet counts in mice

Platelet counts were measured to study whether anfibatide would cause thrombocytopenia in mice without stroke. The results (see Supporting Information Fig. S1) showed that platelet counts in anfibatide-treated and tirofiban-treated mice were not statistically different from control mice (P > 0.05). Injection of anfibatide did not alter platelet counts, which did not cause thrombocytopenia.

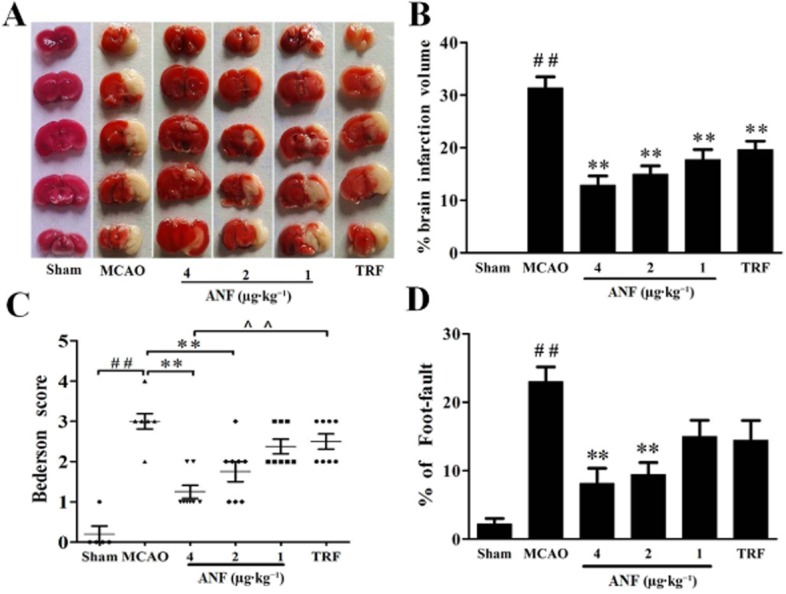

Effect of anfibatide on cerebral infarct volumes in MCAO mice

Effect of anfibatide on cerebral infarct volumes was assayed at 24 h after MCAO. Infarct volumes of the brain were significantly reduced in anfibatide groups compared with the MCAO group (Figure 1A,B). Anfibatide (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1) significantly diminished the infarct size compared with the MCAO only group (P < 0.01, n = 8). Tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) had similar effect on the infarct volumes compared with the MCAO group (P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Effects of anfibatide (ANF) on cerebral infarct volumes and brain functional outcomes in MCAO mice. (A) Representative TTC stains of five corresponding coronal brain sections. Ischaemic infarctions appear white. (B) Brain infarct volumes measured at 24 h after 90 min of MCAO. Neurological Bederson score (C) and foot fault test (D) assessed at day 1 after MCAO. Sham group (n = 6), MCAO group (n = 8), mice treated with anfibatide (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1, n = 8, respectively) and mice treated with tirofiban (TRF, 0.5 mg·kg−1, n = 8). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ##P < 0.01 compared with the sham group; **P < 0.01 compared with the MCAO group.

Effect of ANF on brain functional outcomes in MCAO mice

The modified Bederson score that assesses neurological function and the foot fault test that measures motor function and coordination were used to study the effects of anfibatide on functional outcomes in MCAO mice. The MCAO group showed remarkable differences in functional outcomes compared with the sham group (Figure 1C,D). Anfibatide (4 μg·kg−1) mice showed significant improvement in neurological functions compared with the MCAO group (Bederson score, 1.25 ± 0.16 vs. 3.0 ± 0.16, P < 0.01; foot fault test, 8.14 ± 2.21 vs. 23.0 ± 2.16, P < 0.01). Although the tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) mice tended to develop less severe neurological deficits compared with the MCAO group, there was no statistical difference between the two groups in the Bederson score or the foot fault test.

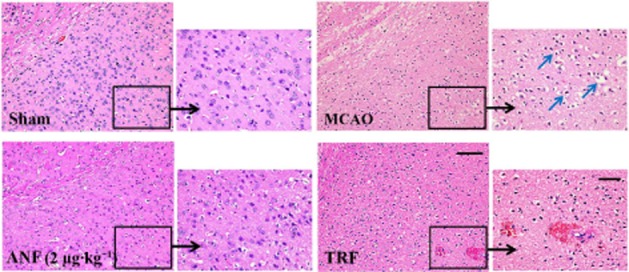

Effect of ANF on histopathology of brain tissues in MCAO mice

H&E-stained sections showed great morphological differences in lesion development between sham and MCAO mice (Figure 2). Sham mice revealed normal structure neuron cells with clear edge, nuclei and intercellular substance stained evenly. Cerebral tissue in the MCAO mice showed vacuolar necrosis, enlarged interspaces, intercellular oedema and ill-defined cells. The nuclei displayed irregular, pyknotic and hyperchromatic changes. Treatment with anfibatide (2 μg·kg−1) attenuated brain damage to varying degrees, including the reduction of neuronal necrosis and intercellular oedema. tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) could also decrease cerebral ischaemia damage. However, haemorrhage in the ischaemic hemispheres could be seen in some of the anti-GPIIb/IIIα-treated mice.

Figure 2.

Effect of anfibatide (ANF) on histopathology in brain tissues in MCAO mice. H&E-stained sections of corresponding regions in the ischaemic hemispheres of mice in each group at 24 h after MCAO. Scale bar: 100 μm (left); 50 μm (right). Blue arrows indicated vacuolar degeneration and irregular, pyknotic and hyperchromatic nuclei.

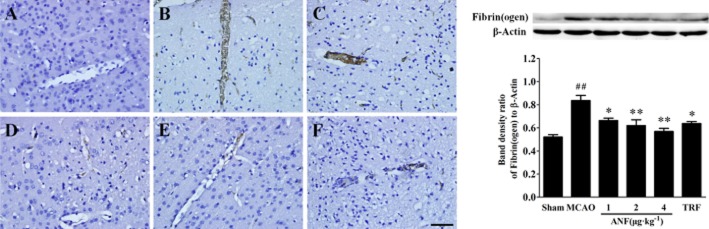

Effect of anfibatide on the accumulation of fibrin(ogen) in MCAO mice

Effect of anfibatide on the accumulation of fibrin(ogen) was assayed via immunohistochemistry and Western blot in the ischaemic hemispheres. The results (Figure 3) showed a clear increase of fibrin(ogen) expression in MCAO group compared with the sham group (P < 0.01), whereas anfibatide (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1) treatment significantly decreased the deposition compared with the MCAO group. Tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) also inhibited the fibrin(ogen) expression compared with the MCAO group (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of anfibatide (ANF) on the accumulation of fibrin(ogen) in brain tissues in MCAO mice. Left: immunostaining of fibrin(ogen)-positive vessels in the ischaemic cortex at 24 h after MCAO. (A) Sham group; (B) MCAO group; (C) anfibatide (1 μg·kg−1) group; (D) anfibatide (2 μg·kg−1) group; (E) anfibatide (4 μg·kg−1) group; (F) tirofiban (TRF; 0.5 mg·kg−1) group. Scale bar = 50 μm. Right: Western blot analysis of fibrin(ogen) expression. Top: a representative Western blot image of fibrin(ogen) collected from the ischaemic cortex 24 h after MCAO. Bottom: grey value of Western blot analysis of fibrin(ogen) expression. n = 3 in each group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ##P < 0.01 compared with the sham group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the MCAO group.

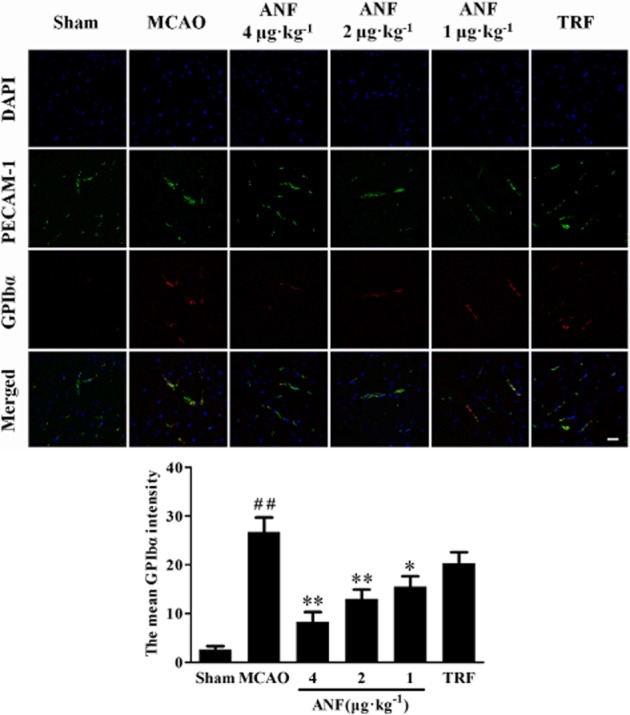

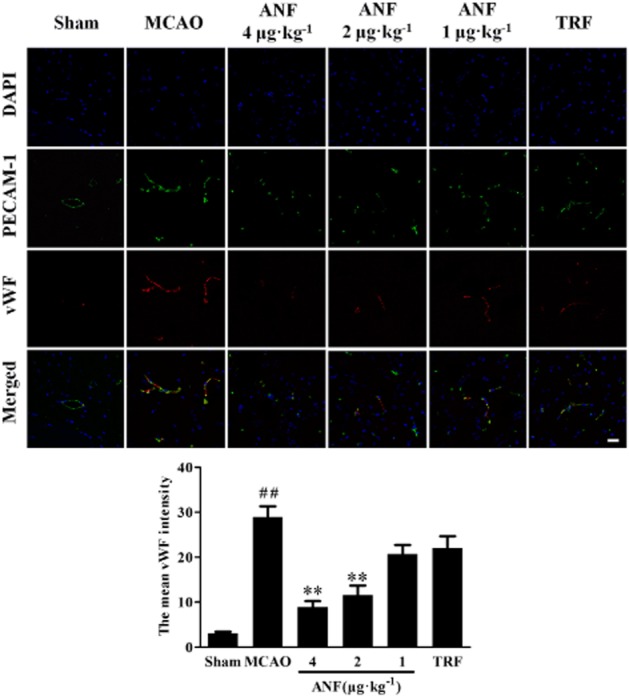

Effect of anfibatide on the abundance of GPIbα and vWF in MCAO mice

The expressions of GPIbα and vWF after cerebral ischaemia were observed by double labelling immunofluorescent staining. As shown in Figure 4 (GPIbα) and Figure 5 (vWF), vasculature that was positive for immunofluorescence of GPIbα and vWF was rarely found in sham group. However, much of the vasculature was positive for immunofluorescence of GPIbα and vWF in the ischaemic hemispheres in MCAO mice. Anfibatide (4, 2 μg·kg−1) treatment significantly reduced the abundance of GPIbα (P < 0.01) and vWF (P < 0.01) compared with the model group. Tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) treatment showed no difference in expressions of GPIbα and vWF compared with the MCAO group (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of anfibatide (ANF) on the abundance of GPIbα in the ischaemic hemispheres of mice (immunofluorescence staining). (Top) Double-fluorescent staining for PECAM-1 (endothelial cell marker, green) and GPIbα (red), cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). It shows that platelet deposition and PCEAM-1 immunoreactivity colocalized to ipsilateral microvessels, although some PECAM-1-immunoreactive vessels did not exhibit platelet deposition. (Bottom) The mean intensity of GPIbα. n = 5 in each group. Scale bar = 25 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ##P < 0.01 compared with the sham group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the MCAO group.

Figure 5.

Effect of anfibatide (ANF) on the amount of vWF in the ischaemic hemispheres of mice (immunofluorescence staining). (Top) Double-fluorescent staining for PECAM-1 (endothelial cell marker, green) and vWF (red), cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). (Bottom) The mean intensity of vWF. n = 5 in each group. Scale bar = 25 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ##P < 0.01 compared with the sham group, **P < 0.01 compared with the MCAO group.

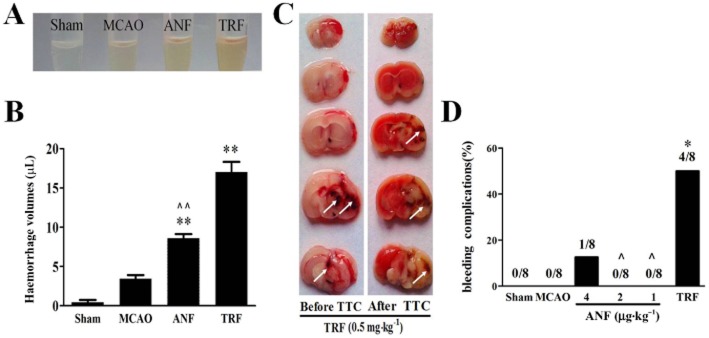

Effect of anfibatide on the risk of ICH in MCAO mice

Impacts of anfibatide on intracerebral bleeding after MCAO were analysed. Measurement of whole blood by spectrophotometric assay showed a linear relationship between volume of added blood and the haemoglobin absorbance. Results showed that there was no difference in haemorrhage volumes between the sham group and the MCAO group (Figure 6A,B). Treatment with anfibatide 4 μg·kg−1 and tirofiban 0.5 mg·kg−1 significantly increased haemorrhage volumes compared with the MCAO group. However, the increase in haemorrhage volumes induced by anfibatide was almost 50% less pronounced than tirofiban treatment (P < 0.01). Moreover (Figure 6C,D), a high incidence of ICH was observed in tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) group (P < 0.05). In contrast, only one animal from all of the anfibatide treatment (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1) groups showed ICH (P > 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of anfibatide (ANF) on intracerebral haemorrhage in MCAO mice. (A) Supernatants of right (ischaemic) hemisphere homogenates. (B) Haemorrhagic volume was determined by haemoglobin brain tissue analysis using quantitative spectrophotometric haemoglobin assay. (A and B) ANF indicates anfibatide 4 μg·kg−1, TRF indicates tirofiban 0.5 mg·kg−1. n = 6 in each group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01 compared with the MCAO group. ∧∧P < 0.01 compared with the tirofiban group. (C) Representative images of five corresponding coronal brain sections, before and after TTC staining, from two mice treated with tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1), undergoing 90 min cerebral ischaemia followed by 1 h reperfusion. Note the massive haemorrhages (white arrows) within the infarcted brain area. Also, there was almost no haemorrhaging that could be seen in the brains of MCAO mice. (D) Percentage of ICH at 24 h after tMCAO. The total number of mice in each group was eight. *P < 0.05, chi-squared statistics test compared with the MCAO group. ∧P < 0.05, chi-squared statistics test compared with the tirofiban group.

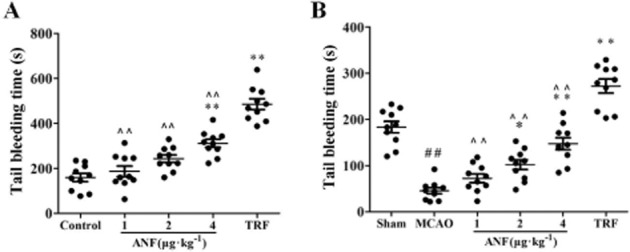

Effect of anfibatide on haemostasis (tail vein bleeding time) in mice

Tail bleeding time was measured to determine anti-haemostatic effect of anfibatide in mice not subjected to MCAO (Figure 7A). The bleeding time averaged 159.5 ± 18.3 s in saline group. Anfibatide (4 μg·kg−1, 311.5 ± 17.6 s) and tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1, 485.7 ± 23.9 s) could significantly increase the bleeding time compared with the control mice (P < 0.01). Anfibatide prolonged bleeding time in a dose-related manner. Meanwhile, anfibatide (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1) led to shorter bleeding time than the tirofiban group (P < 0.01).

Figure 7.

Effect of anfibatide (ANF) on haemostasis (tail vein bleeding time) in mice. (A) Bleeding time was measured in mice that were not subjected to experimental manipulation. The tested drugs were i.v. administered to mice 30 min before the tail transection. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM for 10 mice from each group. **P < 0.01 compared with the control group, ∧∧P < 0.01 compared with the tirofiban (TRF) group. (B) Tail bleeding time was also examined in MCAO mice at 24 h after reperfusion. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM for 10 mice from each group. ##P < 0.01 compared with the sham group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the MCAO group, ∧∧P < 0.01 compared with the tirofiban group.

Tail bleeding time was also examined to study the effect of anfibatide on haemostasis in MCAO mice. Results showed (Figure 7B) that bleeding time of MCAO mice (45.7 ± 6.6 s) decreased significantly compared with the sham mice (183.3 ± 12.4 s, P < 0.01). Anfibatide (4, 2 μg·kg−1) could significantly increase the bleeding time compared with the MCAO mice (P < 0.05, P < 0.01). Meanwhile, tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) also prolonged the bleeding time compared with the MCAO mice (P < 0.01), and led to longer bleeding time than the anfibatide group (4, 2, 1 μg·kg−1, P < 0.01).

Discussion

Anfibatide is a C-type lectin-like protein derived from a snaclec purified from the venom of the Agkistrodon acutus snake. Studies have demonstrated that anfibatide is a potent antithrombotic agent (Lei et al., 2014). In the present study, we evaluated the effect of this novel GPIb antagonist in protection from ischaemic stroke and reperfusion injury. Results showed that blockade of GPIb with anfibatide was protective against the neuronal damage and pathological deterioration induced by 90 min of MCAO. Moreover, anfibatide treatment also decreased the amount of GPIbα and vWF and the accumulation of fibrin(ogen) in the vasculature of the ischaemic hemispheres in MCAO mice. It confirmed previous reports that GPIb blockade is protective in the setting of ischaemic stroke (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007; Stoll et al., 2008; 2010,). It also provided the first experimental evidence that GPIb blockade via anfibatide might be an alternative to the use of antibody derivatives (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007; Momi et al., 2013).

Thrombus formation is of paramount importance in the pathophysiology of acute ischaemic stroke and reperfusion injury. Platelet adhesion and aggregation at sites of vessel injury are crucial in post-traumatic loss of blood and play a central role in acute ischaemic stroke (Del Zoppo and Mabuchi, 2003). GPIb antagonists are currently considered powerful inhibitors of platelet function as a disruptor of the initial stages of platelet adhesion, but anti-GPIb therapy has not yet been developed. GPIb inhibition in our study significantly reduced stroke infarct volumes and improved neurological function even when anfibatide was injected with a delay of 1 h after 90 min of MCAO. This underlines the functional significance of this therapeutic approach and indicates its role in the microthrombus formation during cerebral ischaemia reperfusion injury.

GPIbα is the major platelet membrane GP expressed in platelets and megakaryocytes. After vascular injury, platelets adhere to the exposed subendothelium through GPIb–vWF interaction, which contributes to platelet activation and aggregation. The central role of GPIbα in thrombus formation was confirmed in a study showing that platelet tethering was virtually absent in vessels of IL-4 receptor α/GPIbα-tg mice (lacking the extracellular domain of GPIbα) and there was no thrombus formation within the microvasculature (Bergmeier et al., 2008). Plenty of evidence showed that inhibition of early platelet adhesion by blockade of GPIb could protect animals from ischaemic stroke (Stoll et al., 2008; 2010,; De Meyer et al., 2010; 2011,). Clinical studies also found increased platelet GPIb receptor number, enhanced platelet adhesion and severe cerebral ischaemia in a patient (Toth et al., 2009), and proved that platelet GPIba Kozak polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of ischaemic stroke (Baker et al., 2001). The specific requirement for GPIbα for platelet adhesion and aggregation makes this receptor a potential target for pharmacological inhibition of pathological thrombus formation in related diseases. Blockade of platelet adhesion by anti-GPIb therapy could result in the prevention of cerebral infarction and increased patency of the microcirculation during cerebral ischaemia (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007; Pham et al., 2011; Momi et al., 2013).

It has to be noted that anfibatide-treated and tirofiban-treated mice were observed to have almost no change in platelet counts. We believe that this is unlikely to cause thrombocytopenia. In agreement with previous reports (Gruner et al., 2003; Kleinschnitz et al., 2007), antibody-mediated blockade of the GPIbα receptor and GPIIb/IIIα receptor had no significant effect on peripheral platelet counts.

GPIb can bind different counter receptors on endothelial cells, platelets and neutrophils such as vWF, Mac-1 or P-selectin. But which of these engagements is of particular relevance for stroke development is not clear (Varga-Szabo et al., 2008). vWF is the principal ligand of GPIb and a well-known marker of endothelial activation. Within the ischaemic brain vasculature after MCAO, activated or damaged endothelium stimulate endothelial vWF secretion, the result of this release is activation of platelet adhesion that further amplifies platelet secretion, which produces elevated levels of the vWF expressed on the endothelium and in plasma (Montoro-García et al., 2014). At the site of a wound, where the high shear force activates the vWF (through the A3 domain) bound to collagen by stretching vWF multimers into their filamentous form, then the adhesion is promoted by the interaction of the A1 domain of vWF with GPIbα on the platelet membrane (Ruggeri, 2001). Increased platelet aggregation and pathological thrombus formation strongly rely on endothelial vWF accumulation and plasma vWF adhesion (Westein et al., 2013).

vWF-mediated platelet adhesion to injured vessels is essential for arterial thrombosis. It is also considered as an emerging target in cerebral ischaemia (Varga-Szabo et al., 2008; De Meyer et al., 2012). Investigations of independent case–control studies indicated the association between high vWF levels and the occurrence of a first ischaemic stroke and mortality in humans (Van Schie et al., 2010). Protection of vWF-deficient mice from ischaemic stroke injury (Kleinschnitz et al., 2009), together with enlarged infarct size in ADAMTS13-deficient mice (Fujioka et al., 2010; Khan et al., 2012), suggests an important role of vWF in ischaemic stroke. Besides its role in thrombus formation, mechanisms such as increased vWF activity could contribute to the risk of stroke as well.

Our results showed that the abundance of GPIbα and vWF in the vasculature of infarcted hemispheres was much higher in MCAO mice than sham mice. This increased immunoreactive GPIbα and vWF in the endothelium was significantly correlated with the degree of thrombus formation. Anfibatide could considerably reduce the increased GPIbα and vWF depositions in the ischaemic hemispheres, whereas tirofiban (0.5 mg·kg−1) showed no effect on vWF and GPIbα abundance. Anfibatide therapy was associated with decreased vWF and GPIbα elaboration and deposition, which led to the reduced thrombus formation. Anfibatide exerts its antithrombotic activity by acting as a GPIbα antagonist, blocking GPIbα–vWF mediated primary platelet adhesion and aggregation. Along with other previous studies, our research showed that binding of GPIb to vWF was a mandatory step in ischaemic stroke, suggesting the central role of GPIb for platelet adhesion and stroke formation (Stoll et al., 2008; 2010,). That is not the case for vWF–GPIIb/IIIα interaction, which is consistent with the failure of GPIIb/IIIα blockade in protecting experimental and clinical stroke (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007; Adams et al., 2008; Kellert et al., 2013). These data imply that in events with acute stroke, an ongoing state of reduced platelet adhesion exists, in part due to blockade of the GPIb–vWF interactions, which may give rise to low solution of the existing thrombus and also poor resolution of further fatal thrombotic events.

The immunohistochemical study and the Western blot analysis presented here indicated that at 24 h after reperfusion, lots of fibrin(ogen) formed and accumulated in the ipsilateral microvasculature in MCAO model. Similar finding on fibrin(ogen) deposition in microvessels in MCAO mice was also reported (Tabrizi et al., 1999; De Meyer et al., 2010). These results suggested that the ischaemic injury closely connected with fibrin(ogen) formation. The marked increase of intravascular fibrin(ogen) deposition in ischaemic brain was associated with platelet adhesion and aggregation, even microvascular thrombosis, involving vWF–platelet GPIb receptor and fibrinogen–platelet GPIIb/IIIα receptor interactions, which contributed to form a stable haemostatic plug or thrombus (Massberg et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 1999). Our results showed that fibrin(ogen) deposition was barely detectable in the absence of ischaemic stroke (sham mice). Severe ischaemic cell damage and much intravascular fibrin(ogen) accumulation were observed in MCAO mice, while anfibatide could protect the brain from an ischaemic insult and be effective at decreasing fibrin(ogen) expression in the ischaemic hemispheres. The mechanism may be that anfibatide inhibits the interaction between GPIb and vWF, which leads to less platelet adhesion and less thrombus formation. Also, the absent procoagulant activity of platelets (which serve as surface for the assembly of coagulation complexes) reduces coagulation, which results in less thrombin generation and consequently results in less fibrin(ogen) formation. Moreover, without platelets that interact with each other via fibrin(ogen), less fibrin(ogen) is accumulated in the vessels. This strongly suggested that GPIbα blockade by anfibatide treatment could be useful in ischaemic stroke through inhibition of thrombosis.

Cerebral haemorrhage and bleeding are major complications associated with thrombolytic therapy and antithrombotic therapies. Previous report confirmed that intracranial bleeding was not increased in mouse model of ischaemic stroke when vWF–GPIb binding was blocked even completely (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007). However, blockade of the final common pathway of platelet aggregation with anti-GPIIb/IIIα increased the incidence of ICH and mortality after MCAO (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007; Kellert et al., 2013; Ciccone et al., 2014). Our results showed that tirofiban, a GPIIb/IIIα inhibitor, had effects on the decreased infarct volumes and accumulation of fibrin(ogen), but it was less effective on some stroke outcomes and had higher risk of ICH than anfibatide treatment. Although tail bleeding time was elevated in anfibatide-treated mice, not subjected to MCAO, in a dose-dependent manner, tirofiban resulted in much longer bleeding time, which was in agreement with a similar research (Kleinschnitz et al., 2007).

It is worth noting that cerebral ischaemia is characterized by the state of hypercoagulability and hyperviscosity in circulation, which is prone to form thrombosis (Zhu et al., 2005; Martínez-Martínez et al., 2010). In that case, the significant reduction in bleeding time was observed in MCAO mice because of the change of coagulation system. Our study also assessed the effect of anfibatide and tirofiban on haemostasis in MCAO mice. By anfibatide treatment, the ameliorative hypercoagulable state has been proved due to the longer bleeding time than MCAO mice, but it was still shorter than sham mice; however, tirofiban exerts obviously longer bleeding time than MCAO mice. These results could explain the high frequency of ICH after MCAO due to impaired haemostasis after GPIIb/IIIα blockade. Importantly, it also proved that therapy with anfibatide showed lower incidence of ICH and shorter tail bleeding time compared with the tirofiban-treated mice while providing better protection against ischaemia. These results demonstrate that anfibatide is a potent and safe antithrombotic agent for treatment of cerebral ischaemia compared with tirofiban, a GPIIb/IIIα blocker.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province, China (no. 1208085MH177), the 48th SRF for ROCS, SEM, and Academic and Technological Leader Candidate Foundation of Anhui Province (no. 2014H029) to L.-L. Z.

Glossary

- GP

glycoprotein

- H&E

haematoxylin and eosin

- ICH

intracerebral haemorrhage

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- TTC

2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

Author contributions

T.-T. L., S.-X. H. and L.-L. Z. developed the concept, designed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. T.-T. L., M.-L. F. and S.-X. H. performed the experiments and analysed the data. H. J., S.-Y. L., F. K. performed part of the experiments. X.-Y. L., D. M. B. and L.-F. L. participated in manuscript writing and provided helpful suggestions. X.-R. D. and G.-H. Z. provided helpful suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 Effect of anfibatide on platelet counts in mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 6 in each group. No statistically significant differences were observed (P > 0.05).

References

- Abe T, Kunz A, Shimamura M, Zhou P, Anrather J, Iadecola C. The neuroprotective effect of prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptor inhibition has a wide therapeutic window, is sustained in time and is not sexually dimorphic. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:66–72. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams HP, Jr, Adams RJ, Brott T, del Zoppo GJ, Furlan A, Goldstein LB, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with ischemic stroke: a scientific statement from the Stroke Council of the American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2003;34:1056–1083. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000064841.47697.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams HP, Jr, Effron MB, Torner J, Davalos A, Frayne J, Teal P, et al. Emergency administration of abciximab for treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke: results of an international phase III trial: abciximab in emergency treatment of stroke trial (AbESTT-II) Stroke. 2008;39:87–99. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.476648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: catalytic receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013a;170:1676–1705. doi: 10.1111/bph.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2013b;170:1797–1867. doi: 10.1111/bph.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews RK, Berndt MC. Platelet physiology and thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2004;114:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RI, Eikelboom J, Lofthouse E, Staples N, Afshar-Kharghan V, López JA, et al. Platelet glycoprotein Iba Kozak polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Blood. 2001;1:36–40. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Tsuji M, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski H. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: evaluation of the model and development of a neurologic examination. Stroke. 1986;17:472–476. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeier W, Chauhan AK, Wagner DD. Glycoprotein Ibalpha and von Willebrand factor in primary platelet adhesion and thrombus formation: lessons from mutant mice. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:264–270. doi: 10.1160/TH07-10-0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt MC, Andrews RK. Approaches to the analysis of structure/function of novel membrane receptors: a functional dissection of platelet GP Ib-IX-V. Lett Pept Sci. 2002;8:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccone A, Motto C, Abraha I, Cozzolino F, Santilli I. Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005208.pub3. CD005208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark WM, Lessov NS, Dixon MP, Eckenstein F. Monofilament intraluminal middle cerebral artery occlusion in the mouse. Neurol Res. 1997;19:641–648. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1997.11740874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer SF, Schwarz T, Deckmyn H, Denis CV, Nieswandt B, Stoll G, et al. Binding of von Willebrand factor to collagen and glycoprotein Ibalpha, but not to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, contributes to ischemic stroke in mice – brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1949–1951. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.208918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer SF, Schwarz T, Schatzberg D, Wagner DD. Platelet glycoprotein Ibα is an important mediator of ischemic stroke in mice. Exp Transl Stroke Med. 2011;3:9. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer SF, Stoll G, Wagner DD, Kleinschnitz C. von Willebrand factor: an emerging target in stroke therapy. Stroke. 2012;43:599–606. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.628867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Zoppo GJ, Mabuchi T. Cerebral microvessel responses to focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:879–894. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000078322.96027.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinera AR, Ogle ME, Gu X, Wei L. Citalopram enhances neurovascular regeneration and sensorimotor functional recovery after ischemic stroke in mice. Neuroscience. 2013;247:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M. New approaches to neuroprotective drug development. Stroke. 2011;42:S24–S27. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka M, Hayakawa K, Mishima K, Kunizawa A, Irie K, Higuchi S, et al. ADAMTS13 gene deletion aggravates ischemic brain damage: a possible neuroprotective role of ADAMTS13 by ameliorating post-ischemic hypoperfusion. Blood. 2010;115:1650–1653. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-230110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Ge H, Chen H, Li H, Liu Y, Chen L, et al. Crystal structure of agkisacucetin, a GpIb-binding snake C-type lectin that inhibits platelet adhesion and aggregation. Proteins. 2012;80:1707–1711. doi: 10.1002/prot.24060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner S, Prostredna M, Schulte V, Krieg T, Eckes B, Brakebusch C, et al. Multiple integrin-ligand interactions synergize in shear-resistant platelet adhesion at sites of arterial injury in vivo. Blood. 2003;102:4021–4027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 h after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez TD, Schallert T. Seizures and recovery from experimental brain damage. Exp Neurol. 1988;102:318–324. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(88)90226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Anrather J, Zhou P, Park L, Wang G, Frys KA, et al. Prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptors: downstream effectors of COX-2 neurotoxicity. Nat Med. 2006;12:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nm1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellert L, Hametner C, Rohde S, Bendszus M, Hacke W, Ringleb P, et al. Endovascular stroke therapy: tirofiban is associated with risk of fatal intracerebral hemorrhage and poor outcome. Stroke. 2013;44:1453–1455. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MM, Motto DG, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. ADAMTS13 reduces VWF-mediated acute inflammation following focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1665–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2010;1:94–99. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.72351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschnitz C, Pozgajova M, Pham M, Bendszus M, Nieswandt B, Stoll G. Targeting platelets in acute experimental stroke: impact of glycoprotein Ib, VI, and IIb/IIIa blockade on infarct size, functional outcome, and intracranial bleeding. Circulation. 2007;115:2323–2330. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschnitz C, De Meyer SF, Schwarz T, Austinat M, Vanhoorelbeke K, Nieswandt B, et al. Deficiency of von Willebrand factor protects mice from ischemic stroke. Blood. 2009;113:3600–3603. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei X, Reheman A, Hou Y, Zhou H, Wang Y, Marshall AH, et al. Anfibatide, a novel GPIb complex antagonist, inhibits platelet adhesion and thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo in murine models of thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:279–289. doi: 10.1160/TH13-06-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Chopp M, Ding X, Cui Y, Li Y. Axonal remodeling of the corticospinal tract in the spinal cord contributes to voluntary motor recovery after stroke in adult mice. Stroke. 2013;44:1951–1956. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Martínez M, Cazorla-García R, Rodríguez de Antonio LA, Martínez-Sánchez P, Fuentes B, Diez-Tejedor E. Hypercoagulability and ischemic stroke in young patients. Neurologia. 2010;25:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massberg S, Enders G, Matos FC, Tomic LI, Leiderer R, Eisenmenger S, et al. Fibrin(ogen) deposition at the postischemic vessel wall promotes platelet adhesion during ischemia-reperfusion in vivo. Blood. 1999;11:3829–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momi S, Tantucci M, Van Roy M, Ulrichts H, Ricci G, Gresele P. Reperfusion of cerebral artery thrombosis by the GPIb-VWF blockade with the Nanobody ALX-0081 reduces brain infarct size in guinea pigs. Blood. 2013;121:5088–5097. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-464545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro-García S, Shantsila E, Lip GY. Potential value of targeting von Willebrand factor in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18:43–53. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.840585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu FT, Cranmer SL, Andrews RK, Berndt MC. Functional association of phosphoinositide-3-kinase with platelet glycoprotein Iba, the major ligand-binding subunit of the glycoprotein Ib-IX-V complex. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:324–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham M, Helluy X, Kleinschnitz C, Kraft P, Bartsch AJ, Jakob P, et al. Sustained reperfusion after blockade of glycoprotein-receptor-Ib in focal cerebral ischemia: an MRI study at 17.6 Tesla. PLoS ONE. 2011;4:e18386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri ZM. Structure of von Willebrand factor and its function in platelet adhesion and thrombus formation. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2001;14:257–279. doi: 10.1053/beha.2001.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Fish BL, Moulder JE, Medhora M, Baker JE, Mader M, et al. Safety and blood sample volume and quality of a refined retro-orbital bleeding technique in rats using a lateral approach. Lab Anim (NY) 2014;43:63–66. doi: 10.1038/laban.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll G, Kleinschnitz C, Nieswandt B. Molecular mechanisms of thrombus formation in ischemic stroke: novel insights and targets for treatment. Blood. 2008;112:3555–3562. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-144758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll G, Kleinschnitz C, Nieswandt B. The role of glycoprotein Ibalpha and von Willebrand factor interaction in stroke development. Hamostaseologie. 2010;30:136–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugidachi A, Asai F, Ogawa T, Inoue T, Koike H. The in vivo pharmacological profile of CS-747, a novel antiplatelet agent with platelet ADP receptor antagonist properties. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:1439–1446. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumii T, Lo EH. Involvement of matrix metalloproteinase in thrombolysis-associated hemorrhagic transformation after embolic focal ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2002;33:831–836. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.104542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Hattori K, Hamanaka J, Murase T, Egashira Y, Mishiro K, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of TLR4-NOX4 signal protects against neuronal death in transient focal ischemia. Sci Rep. 2012;2:896–905. doi: 10.1038/srep00896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizi P, Wang L, Seeds N, McComb JG, Yamada S, Griffin JH, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) deficiency exacerbates cerebrovascular fibrin(ogen) deposition and brain injury in a murine stroke model: studies in tPA-deficient mice and wild-type mice on a matched genetic background. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2801–2806. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.11.2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth J, Kappelmayer J, Udvardy ML, Szanto T, Szarvas M, Rejto L, et al. Increased platelet glycoprotein Ib receptor number, enhanced platelet adhesion and severe cerebral ischaemia in a patient with polycythaemia vera. Platelets. 2009;4:282–287. doi: 10.1080/09537100902878421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schie MC, DE Maat MP, Dippel DW, de Groot PG, Lenting PJ, Leebeek FW, et al. Von Willebrand factor propeptide and the occurrence of a first ischemic stroke. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1424–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga-Szabo D, Pleines I, Nieswandt B. Cell adhesion mechanisms in platelets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:403–412. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westein E, van der Meer AD, Kuijpers MJ, Frimat JP, van den Berg A, Heemskerk JW. Atherosclerotic geometries exacerbate pathological thrombus formation poststenosis in a von Willebrand factor-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1357–1362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209905110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZG, Chopp M, Goussev A, Lu D, Morris D, Tsang W, et al. Cerebral microvascular obstruction by fibrin(ogen) is associated with upregulation of PAI-1 acutely after onset of focal embolic ischemia in rats. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10898–10907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10898.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao BQ, Ikeda Y, Ihara H, Urano T, Fan W, Mikawa S, et al. Essential role of endogenous tissue plasminogen activator through matrix metalloproteinase 9 induction and expression on heparin-produced cerebral hemorrhage after cerebral ischemia in mice. Blood. 2004;103:2610–2616. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu HB, Zhang L, Wang ZH, Tian JW, Fu FH, Liu K, et al. Therapeutic effects of hydroxysafflor yellow A on focal cerebral ischemic injury in rats and its primary mechanisms. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2005;7:607–613. doi: 10.1080/10286020310001625120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Effect of anfibatide on platelet counts in mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 6 in each group. No statistically significant differences were observed (P > 0.05).