Abstract

Background

We have previously reported that an eccentrically-based rehabilitation protocol post-ACLr induced greater quadriceps activation and strength than a neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) intervention and was just as effective as a combined NMES and eccentric intervention. However, the effect an eccentrically-based intervention has on restoring normal knee mechanics during a single-legged landing task remains unknown.

Methods

Thirty-six individuals post-injury were placed into four treatment groups: NMES and eccentrics, eccentrics-only, NMES-only, standard of care, and Healthy controls participated. NMES and eccentrics received a combined NMES and eccentric protocol post-reconstruction (each treatment 2x per week for 6 wks), whereas groups NMES-only and eccentric-only received only the NMES or eccentric therapy, respectively. To evaluate knee mechanics limb symmetry, the area under the curve for knee flexion angle and extension moment was derived and then normalized to the contralateral limb. Quadriceps strength was evaluated using the quadriceps index.

Findings

Compared to Healthy, reduced sagittal plane knee limb symmetry was found for groups NMES-only, ECC-only and standard of care for knee extension moment (P<0.05). No difference was detected between Healthy and NMES and eccentrics (P>0.06). No difference between groups was detected for knee flexion angle limb symmetry (P>0.05). Greater knee flexion angles and moments over stance were related to quadriceps strength.

Interpretation

The NMES and eccentrics group was found to restore biomechanical limb symmetry that was most closely related to Healthy individuals following ACL reconstruction. Greater knee flexion angles and moments over stance were related to quadriceps strength.

Keywords: ACL, knee, rehabilitation, strength testing, biomechanics

1.1 Introduction

The restoration of quadriceps muscle strength following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is a major challenge for patients and rehabilitation specialists. Often, despite clinicians’ best efforts, quadriceps weakness persists long after the rehabilitation period has ended (Keays et al., 2010; Palmieri-Smith et al., 2008; Tourville et al., 2014). This persistent weakness can cause significant alterations in daily life, as it can lead to altered movement patterns (Lewek et al., 2002; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991) that are associated with decreased functional performance and possibly re-injury (Schmitt et al., 2012). Accordingly, rehabilitation approaches that target, and combat, quadriceps weakness may be able to reduce the biomechanical alterations that are associated with the lingering strength deficits.

Previous work has found that quadriceps strength post-ACL reconstruction is significantly related to alterations in sagittal plane knee motion (Lewek et al., 2002; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991). Specifically, during walking and jogging tasks, patients that exhibited greater post-operative quadriceps strength demonstrated movement patterns that were indistinguishable from individuals that are non-injured (Lewek et al., 2002) and their non-injured limb (Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991). Wherein patients with quadriceps strength deficits displayed reduced knee flexion angles (Lewek et al., 2002; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991) and extension moments during activity (Lewek et al., 2002). Thus, it seems that if clinicians can identify and implement therapeutic interventions that are capable of improving the recovery of quadriceps strength, they can positively influence sagittal plane knee mechanics, which should help to improve functional performance and possibly reduce the occurrence of re-injury (Oberländer et al., 2013).

In our own work, we have previously demonstrated that the application of a combined neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) and eccentric exercise intervention is one such therapeutic approach that can induce significant and clinically meaningful gains in quadriceps strength post-ACL reconstruction (Lepley et al., 2015). This 12-week post-operative combined NMES and eccentric exercise intervention (6 weeks of NMES and followed by 6 week of eccentric exercise) was compared to the standard of care post-ACL reconstruction, and the separate application of just the NMES or eccentric exercise therapy. In general, our previous work indicated that eccentric exercise was likely the driving factor behind strength gains, as patients that were exposed to eccentrics recovered quadriceps strength better than those that were not. Additionally, the combined effect of NMES and eccentrics was not found to be superior to isolated eccentrics exercise post-surgery. Further, patients that received the eccentric intervention were able to demonstrate strength that was similar to non-injured matched healthy controls at a time when they were returned back into participation.

With the above in mind, the motivation behind this study was to examine the capability of the combined NMES and eccentric exercise intervention to improve sagittal plane knee symmetry after ACL reconstruction. We chose to specifically investigate the sagittal plane, as alterations in this plane are consistently observed following ACL reconstruction (Hart et al., 2010; Lewek et al., 2002; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991), and the sagittal plane is where the quadriceps muscle has the most influence (Herzog et al., 2003; Hurley, 1999). Though our previous work indicates that eccentric exercise is effective at restoring muscle strength,(Lepley et al., 2015) knowing if these improvements in strength translate to better movement profiles during functional tasks is equally important. Moreover, understanding the benefit of our therapeutic approach to improve knee symmetry will help to provide preliminary evidence of therapies that can positively influence movement after ACL reconstruction that in part, will help to justify the necessity of this intervention to be examined using a large randomized controlled trial. As such, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of our combined NMES and eccentric exercise intervention on sagittal plane knee mechanics post-ACL reconstruction during a dynamic landing task. We hypothesized that compared with the standard of care and the NMES-only intervention; an eccentrically-based rehabilitation program, which was found to reinstitute normative quadriceps function in our previous work (Lepley et al., 2015), would result in a greater measure of sagittal plane knee limb symmetry, wherein these patients would demonstrate knee flexion angles and moments that more closely resemble their contralateral non-injured limb during dynamic activity. Furthermore, we hypothesized that greater quadriceps strength limb symmetry would be positively associated with greater biomechanical limb symmetry.

2.1 Methods

2.1.1 Participants

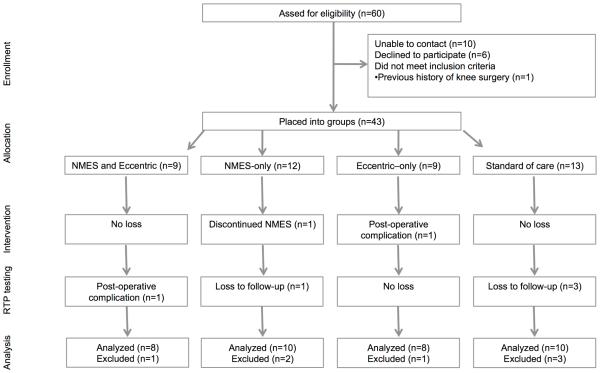

This study sample consisted of the same patients and participants that participated in our previous study (Lepley et al., 2015) (Figure 1, Table 1). Prior to the recruitment of participants, this trial was prospectively registered in a public registry (NCT01555567). A priori power analysis determined that six participants per group would be needed based off previous work examining the effectiveness of NMES to improve quadriceps function after ACL reconstruction (projected effect size 3.66 for quadriceps strength, α-level 0.05, 1-β 0.80) (Wigerstad-Lossing et al., 1988).

Figure 1.

Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) diagram. NMES= neuromuscular electrical stimulation, RTP=return-to-play.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (mean (SD))

| Surgery Details | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | Gender | Age (yrs) | Height (m) | Mass (kg) | Graft | Meniscus | Time-to-Return-to- Play (days) |

| PT=7 | ACL-only=7 | |||||||

| NMES&ECC | 8 | 3f/5m | 23.2(6.3) | 1.4(0.6) | 77.8(16.5) | 208.5(26.3) | ||

| STG=1 | Meniscal Repair=1 | |||||||

| ACL-only=5 | ||||||||

| NMES-only | 10 | 2f/8m | 21.8(4.4) | 1.7(0.1) | 81.6(22.6) | PT=10 | Meniscal Repair=4 | 215.9(30.2) |

| Meniscectomy=1 | ||||||||

| PT=6 | ACL-only=6 | |||||||

| ECC-only | 8 | 3f/5m | 23.2(5.4) | 1.7(0.1) | 77.7(10.4) | 228.8(39.4) | ||

| STG=2 | Meniscal Repair=2 | |||||||

| ACL-only=5 | ||||||||

| PT=8 | ||||||||

| STND | 10 | 5f/5m | 18.3(3.7) | 1.7(0.1) | 75.5(24.1) | Meniscal Repair=4 | 220.1(27.5) | |

| STG=2 | ||||||||

| Meniscectomy=1 | ||||||||

| Healthy | 10 | 3f/7m | 23.5(3.4) | 1.7(0.1) | 71.7(9.9) | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||||

| ACL-only=23 | ||||||||

| Total | 46 | 17f/29m | 21.9(4.9) | 1.6(0.2) | 76.8(17.6) | PT=31 STG=5 |

Meniscal Repair=11 |

218.7(31.3) |

| Meniscectomy=2 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: ECC-only, eccentric-only; f, female; m, male; NMES&ECC, NMES and eccentrics; PT, bone-patellar-tendon-bone graft; STG, semitendinosus/gracilis graft

Briefly, individuals that were scheduled for ACL reconstruction at the University of XXXX were invited to participate. Of the 36 patients with ACL reconstruction that elected to participate, 13 females and 23 males were placed into intervention groups. The average age of all patients with ACL reconstruction was 21.4±5.2 years of age. Thirty-one patients received bone-patellar-tendon autografts and five received semitendinosus and gracilis autografts. Participants were eligible for enrollment if they met the following criteria: 1) were between 14-30 years of age, 2) were planning to undergo rehabilitation at our orthopedic clinic, 3) had an acute ACL injury (defined as reporting to a physician within 48 hours post-injury), 4) had no previous history of surgery to either knee, 5) had not suffered a previous ACL injury and 6) or had a known heart condition. Pregnant females were also excluded. Individuals that elected to participate in the Healthy group, were selected from a convenient sample of university students (3 females and 7 males; 23.5±years) that were free from lower extremity injury within the past 6 months, had no known heart condition, had not suffered an ACL injury, and had no history of surgery to either lower extremity. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board prior to testing.

The details of our institutional post-operative rehabilitation protocol can be found in Appendix A. In general, this rehabilitation protocol consisted of 2 to 3 physical therapy appointments per week that began at the first post-operative appointment following ACL reconstruction (average time to first appointment was 6.5±2.9 days post-surgery) and concluded at approximately 7 months post-surgery (7.3±1.0 months post-surgery). This rehabilitation protocol emphasized range of motion early, quadriceps re-education and muscle strengthening, and progression to functional exercises. Individual variations between rehabilitation protocols were dependent on concomitant meniscal surgery (Table 1), patient age, and response to treatment. At the end of formalized physical therapy, patients were cleared for participation once they had completed a basic 3-week agility program and a leg press test. To pass the leg press test, the clinical protocol requires patients to complete at least 15 repetitions at 100% of body weight with the ACL reconstructed limb from a resting position to a depth of 90° of knee flexion. If a patient did not complete the agility program or was unable to successfully pass the leg press test, their clearance for participation was delayed.

2.1.2 Design overview

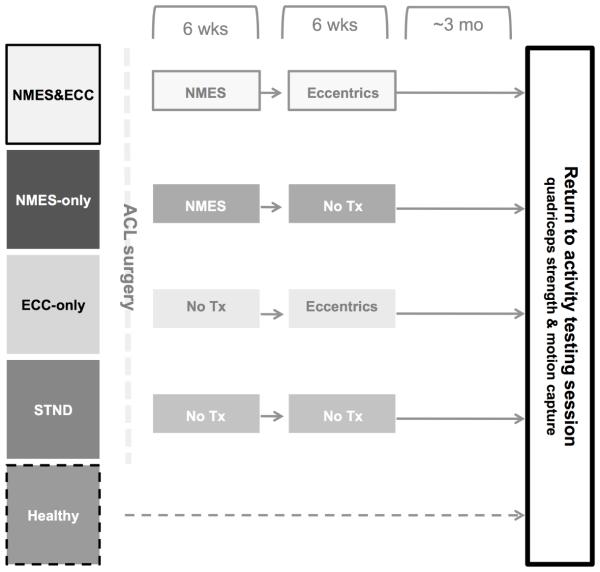

Figure 2 illustrates the study timeline. The details of our intervention have been previously described (Lepley et al., 2015), however in general, our primary investigation utilized a parallel longitudinal design, wherein ACL patients were placed into groups. At the first post-operative rehabilitation appointment, patients in the combined NMES and eccentric exercise (NMES&ECC) and NMES (NMES-only) groups began the 6-week NMES therapy protocol. At six weeks post-operative, the NMES&ECC and eccentric (ECC-only) groups began the eccentric strengthening program. Patients in the standard of care (STND) group did not receive either the NMES or eccentric strengthening study protocol and underwent the standard ACL rehabilitation protocol that is utilized at our institution. At return to activity, motion capture and quadriceps strength data was collected to assess potential differences in knee mechanics and strength between groups. Healthy participants also participated in this final data collection for the purpose of comparing the effectiveness of our intervention to normative data from healthy participants. Importantly, though patients were placed into groups, no differences in participant demographics (age, height, weight), pre-operative level of quadriceps function, and time between testing sessions existed (Lepley et al., 2015).

Figure 2.

Study testing timeline. Upon confirmation of ACL rupture, ACL patients were place into one of four groups. All ACL patients and healthy individuals participated in one testing session at return-to-play, wherein quadriceps strength and knee mechanics were measured. The faded colors represent the intervention that were previously described in our work (Lepley et al., 2015). Patients in the combined NMES and eccentric group (NMES&ECC) received the NMES and eccentric protocol post-reconstruction, whereas groups NMES (NMES-only) and eccentrics (ECC-only) received only the NMES or eccentric therapy, respectively. The STND abbreviation represents the group that received the standard of care following ACL reconstruction.

2.1.3 Interventions

ACL patients in all groups received the same basic rehabilitation protocol (Appendix A). The NMES and eccentric treatments were considered to be adjunct treatment(s) to the overall post-operative treatment plan (i.e. treatments in addition to the standard of care). Thus, we did not strictly control the basic rehabilitation protocol that is utilized at our institution.

Patients placed into groups NMES&ECC and NMES-only received the NMES intervention two times per week for six weeks following ACL reconstruction (Figure 2). Patients in the STND and ECC-only groups did not receive this treatment. As previously described (Lepley et al., 2015), to receive the NMES treatment, patients were positioned in a dynamometer with their hips flexed to 90°, ACL knee flexed to 60° and their back supported (Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991). Stimulating electrodes were placed over the vastus lateralis proximally and the vastus medialis distally and the Intelect Legend XT (Chattanooga Medical Supply, Chattanooga, TN) was set to deliver a 2500 Hz alternating current, modulated at 75 bursts per second, with a ramp-up time of 2 seconds, followed by a 50-second rest period (Fitzgerald et al., 2003; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991). Patients were encouraged tolerate the stimulus at maximal tolerance level and to relax while the NMES was delivered in order to avoid voluntary quadriceps contraction and hamstring co-contraction. Ten isometric contractions lasting 10 seconds each were elicited during each session. This NMES protocol was developed based on previous work in patients that had undergone ACL reconstruction and has been found to improve post-operative quadriceps strength (Fitzgerald et al., 2003; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991).

Patients placed into Group NMES&ECC and ECC-only received eccentric exercise two times per week for six weeks, beginning six weeks post-ACL reconstruction (Figure 2). NMES-only and STND patients did not receive this intervention. As previously described (Lepley et al., 2015), to perform the exercise, patients were positioned in a BLAST!™ Leg Press (BLAST! Leg Press version 1.2, Bio Logic Engineering Inc., Dexter, MI, USA) with their ACL-reconstructed knee range of motion limited to approximately 20 to 60° of knee flexion (Gerber et al., 2007). Once correctly positioned, patients performed a warm-up trial. Following the warm-up, patients completed four sets of ten eccentric contractions with two minutes rest in between each set. During the eccentric contractions, patients were encouraged to train at a minimal intensity equal to 60% of their ACL reconstructed limb one-repetition maximum, consistent with published data indicating that load intensities of at least 60% of the one-repetition maximum are adequate to induce strength (Dwyer and Davis, 2008). The training intensity of eccentric actions was based on each participant’s one-repetition maximum collected at the first session each week (average training intensity over the course of the eccentric exercise intervention was 108.1±31.6% of participant’s concentric one-repetition maximum). No difference in the training intensity was detected between groups NMES&ECC and ECC-only groups (range of mean training intensity over the course of the intervention, NMES&ECC: 96.1-109.4% one-repetition maximum; ECC-only: 93.3-135.3% one-repetition maximum; P>0.05) (Lepley et al., 2015).

2.1.4 Outcomes

To assess quadriceps strength, patients were positioned in an isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex System 3, Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY, USA) with their hips flexed to 90°, their back supported, and their testing leg and torso strapped securely into the dynamometer. Once correctly positioned, patients performed three maximal knee extension maximal voluntary isometric (MVIC) trials with the knee flexed to 90°. The maximal knee extension torque produced across the three isometric trials with the ACL reconstructed limb was then normalized to body weight. The contralateral, non-injured limb quadriceps strength was also evaluated using the same protocol to quantify the recovery of quadriceps strength in the ACL reconstruction limb. For statistical analysis, the quadriceps index (QI) was utilized (Equation 1) (Chmielewski et al., 2004). Healthy individuals also underwent the same testing scheme and had the right and left limb analyzed using the same protocol, wherein all right limbs of healthy participants were arbitrarily labeled as the matched ‘reconstructed limb’.

Equation 1 Quadriceps index

2.1.5 Single-legged landing task

All patients underwent motion analysis testing during a dynamic single-legged landing task. Three-dimensional biomechanical data were collected for the knee joint complex using a Vicon system (Vicon, Oxford Metrics, London, England) sampling at 240 Hz synchronized with the force plate (OR 6-7; Advanced Medical Technology, Inc, Watertown, MA) sampling at 1200 Hz. The landing task required patients to perform a single-leg forward hop onto a force plate with the ACL reconstructed limb or contralateral limb, which was pre-determined prior to the trial. The hop distance was determined by measuring each participant’s leg length, defined as the distance between the tip of the greater trochanter to the tip of the lateral malleolus (Webster et al., 2004). The distance to hop was then visually marked on the ground with a tape measure. Trials were collected until at least three successful trials were achieved on the reconstructed and non-injured limbs, or right and left limbs in the case of healthy participants. Successful trials were defined as trials in which participants landed on the force platform and were able to balance on their take-off limb without touching the floor with the contralateral limb, or losing balance with the take-off limb, or an additional hop at landing (Noyes et al., 1991).

2.1.6 Kinematic and kinetic data processing

Lower limb joint rotations were defined based on three-dimensional coordinates of 32 precisely located retro-reflective markers (right and left limb; anterior and posterior superior iliac spines, iliac crest, greater trochanter, distal thigh, medial and lateral femoral epicondyles, tibial tuberosity, distal shank, lateral shank, medial and lateral malleoli, calcaneus, dorsal navicular, head of first and fifth metatarsal). An initial static trial of each participant aligned with the laboratory coordinate system was recorded, from which a kinematic model comprising of seven skeletal segments (bilateral foot, shank and thigh segments and the pelvis) and 24 degrees of freedom (6 degrees of freedom for the pelvis relative to the global coordinate system, 3 degrees of freedom for the hip, knee and ankle relative to the local coordinate system) was created in Visual3D version 4.0 software (C-Motion; Rockville, MD) (McLean et al., 2004b). The three-dimensional marker trajectories recorded during each dynamic landing trial were subsequently processed within the respective subject’s Visual3D model to solve for the generalized coordinates of each frame. Rotations were calculated utilizing the Cardan rotation sequence (XYZ) (Cole et al., 1993) and were expressed relative to each subject’s neutral static position (McLean et al., 2007). Three-dimensional ground reaction force data was sampled and synchronized with the kinematic data and both were filtered using a fourth-order, zero-lag, low-pass Butterworth filter at 12 Hz cut-off frequency (Myer et al., 2007). Filtered kinematic and ground reaction force data were then submitted to a standard inverse dynamics approach within Visual3D (Willson and Davis, 2008). Segmental inertial properties were defined based on the previous work of Dempster (1959). The intersegmental moments at the knee joint were expressed as flexion-extension, adduction-abduction, and internal-external rotational moments with respect to the Cardan axes of the local joint coordinate system (McLean et al., 2007; McLean et al., 2005). Kinetic outputs were normalized to subject body height and mass and represented as internal moments (Chmielewski et al., 2001), wherein a positive knee extensor moment at the knee would therefore represent the moment production by the quadriceps muscles.

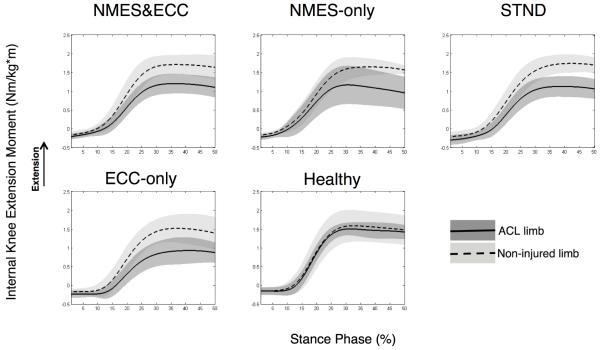

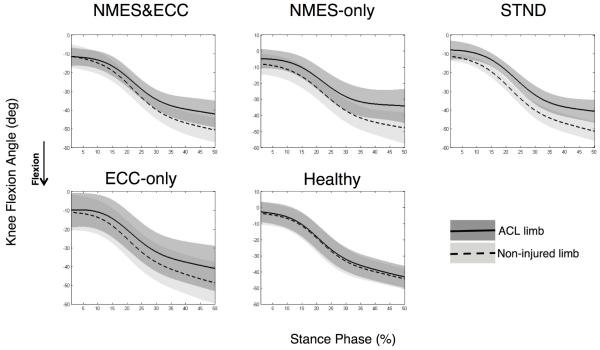

Biomechanical data was time normalized to 100% of the stance phase for graphical purposes, with initial contact equating to the time when the vertical ground reaction force first exceeded 10 N (Borotikar et al., 2008; McLean et al., 2007) and the end of landing equating to 250 msec post-initial contact (Deneweth et al., 2010). Initial foot contact to 250 msec post-ground contact was selected, as this time interval captured the primary loading phases of the knee (i.e. maximal knee flexion peak and knee extension moment and peak vertical ground reaction force) during our single-legged hopping task. Ensemble averages were then calculated across stance for all rotations and moments (McLean et al., 2004a). From these ensemble averages, the area under the curve (Equation 2) was calculated for sagittal knee joint rotations and moments over stance. The area under the curve was chosen over peak angle or moment values because this integral accounts for the total contribution of a joint angle or moment during motion. Specifically, the area under the curve will take into account both the length as well as the total magnitude of joint motion or muscle force. In this way, the area under the curve is thought to quantify movement more accurately than just peak values (DeVita et al., 1998b). Though the area under the curve is more commonly used for calculating alterations in joint moments,(Andriacchi and Birac, 1993; DeVita et al., 1998a) we chose to apply this integral to both our kinematic and kinetic data, as we sought to quantify alterations in both the length as well as the magnitude of biomechanical events. To account for baseline differences in how each patient would accomplish this landing task, the area under the curve integrals (angle and moment) for the ACL reconstructed limb was normalized to the contralateral non-injured limb (right limb normalized to left limb for healthy participants) utilizing the limb symmetry index for knee mechanics (Equation 3) (de Jong et al., 2007). In this way, each participant’s healthy non-injured limb was used as their own control. Though there are inherent issues with utilizing the healthy limb as a control post-ACL injury and reconstruction as potential contralateral quadriceps strength deficits have been reported (Hiemstra et al., 2007), comparing alterations in knee mechanics between limbs with the limb symmetry index is a clinically applicable technique. Thus utilizing the contralateral limb in our analysis allowed us to account for baseline characteristics in the way each subject accomplishes the task (Teichtahl et al., 2009) (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Knee extension moment limb symmetry plots. Right limb represented as the ‘ACL limb’ for healthy participants. Abbreviations; ECC-only, eccentric-only; NMES-only, NMES&ECC, NMES and eccentrics; STND, standard of care.

Figure 4.

Knee flexion angle limb symmetry plots. Right limb represented as the ‘ACL limb’ for healthy participants. Abbreviations; ECC-only, eccentric-only; NMES-only, NMES&ECC, NMES and eccentrics; STND, standard of care.

Equation 2 Area under the curve

Equation 3 Limb symmetry index

2.1.7 Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measures were biomechanical limb symmetry. To determine the effectiveness of the interventions to improve limb symmetry for biomechanical measures, the limb symmetry indices for knee flexion angle and moments were analyzed using one-way ANOVAs with post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison procedures where appropriate. To determine if differences in the limb symmetry index that were found to be statistically significant were clinically meaningful, standardized effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Effect sizes were interpreted using the guidelines described by Cohen (Cohen, 1977), with values less than 0.5 interpreted as weak; values ranging from 0.5-0.79 interpreted as moderate and values greater than 0.8 interpreted as strong. Lastly, to examine the relationship between quadriceps strength and knee mechanics, simple linear regressions were utilized to evaluate the relationship between 1) QI and limb symmetry index for knee extension moment and 2) QI and limb symmetry index for knee flexion angle. The α-level was set a priori at P≤0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3.1 Results

3.1.1 Knee mechanics

At return to activity following ACL reconstruction significant differences between groups were observed, indicating that biomechanical limb symmetry indices differed between groups for the area under the curve for knee flexion angles and moments (Angle: P=0.049; Moment: P=0.01). Specifically, compared to Healthy individuals, groups NMES-only (P=0.02, d=1.75, CI=0.72, 2.78), ECC-only (P=0.01, d=1.95, CI=0.83, 3.09) and STND (P=0.01, d=1.97, CI=0.90, 3.04) demonstrated significantly lower, and clinically meaningful, reduced limb symmetry for knee extension moments. This reduced limb symmetry was driven by small knee extension moments with the ACL reconstructed limb (Table 2, Figure 3). Group NMES&ECC observationally displayed reduced knee extension moments with their ACL reconstructed limb that were clinically meaningful (Table 2, d=1.61, CI=0.55, 2.69), but not statistically different from Healthy controls (P=0.06). Furthermore, though an overall main effect of limb symmetry was detected for knee flexion angles, no significant post hoc differences were noted with regards to knee flexion angle (P values range=0.08-1.00; Table 2, Figure 4).

Table 2.

Area under the curve and limb symmetry index (mean (SD))

| Knee Extension Moment | Knee Flexion Angle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area under the curve | Limb Symmetry Index |

Area under the curve | Limb Symmetry Index |

|||

| Group | ACL | Healthy | ACL | Healthy | ||

| NMES&ECC (n=8) | 33.2(9.7) | 50.8(11.1) | 66.7(19.0) | −1362.5(256.7) | −1509.5(302.3) | 92.3(21.1) |

| NMES-only (n=10) | 33.4(17.2) | 50.0(10.2) | 64.2(19.0)* | −1039.2(374.5) | −1412.1(363.6) | 73.3(18.0) |

| ECC-only (n=8) | 21.9(11.2) | 41.6(13.9) | 55.3(24.1)* | −1260.8(500.3) | −1499.8(469.1) | 83.7(23.3) |

| STND (n=10) | 27.5(9.9) | 46.9(9.6) | 58.7(20.1)* | −1238.6(215.9) | −1601.5(161.9) | 78.1(15.9) |

| Healthy (n=10) | 43.5(7.3) | 46.2(15.7) | 99.8(21.6) | −1172.7(342.6) | −1226.6(349.6) | 95.7(11.7) |

Abbreviations: ECC-only, eccentric-only; NMES&ECC, NMES and eccentrics; STND, standard of care

P<0.05, as compared to Healthy

3.1.2 Relationship between quadriceps strength and knee mechanics

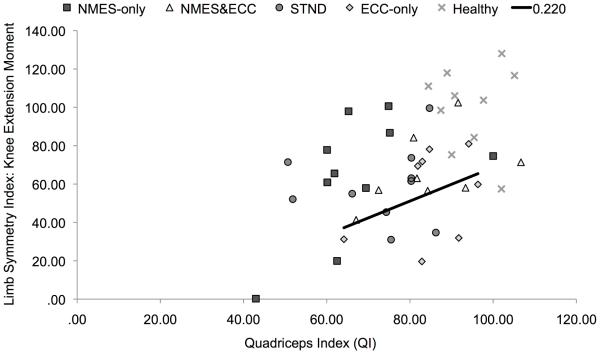

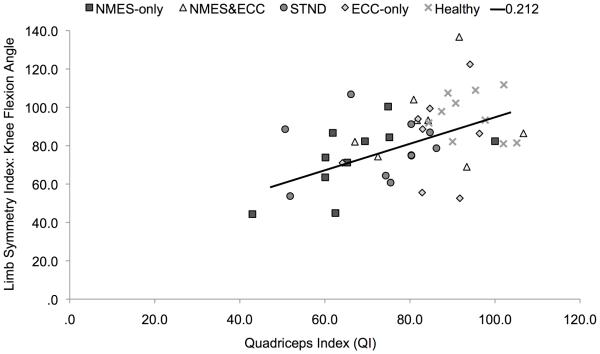

Among all participants, it was found that individuals with greater QIs (Table 3) demonstrated greater biomechanical limb symmetry during the single-legged landing task (QI and Limb Symmetry Index knee extension moment: R2=0.22, b=0.46, P=0.01, Figure 5; QI and Limb Symmetry Index knee flexion angle: R2=0.21, b=0.46, P=0.01, Figure 6).

Table 3.

Quadriceps index (mean (SD))

| Group | Quadriceps Index (QI) |

|---|---|

| NMES&ECC (n=8) | 84.7(12.4) |

| NMES-only (n=10) | 67.2(14.7) |

| ECC-only (n=8) | 84.8(10.1) |

| STND (n=10) | 73.0(12.8) |

| Healthy (n=10) | 94.3(7.0) |

Abbreviations: E-only, eccentric-only; NMES&ECC, NMES and eccentrics; STND, standard of care

Figure 5.

Quadriceps index plotted against knee extension moment limb symmetry index (P=0.001). NMES-only outlier had a QI of 43.10 and a limb symmetry index of 0.24. Abbreviations; ECC-only, eccentric-only; NMES-only, NMES&ECC, NMES and eccentrics; STND, standard of care.

Figure 6.

Quadriceps index plotted against limb flexion angle limb symmetry index (P=0.001). Abbreviations; ECC-only, eccentric-only; NMES-only, NMES&ECC, NMES and eccentrics; STND, standard of care.

4.1 Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of a combined NMES and eccentric exercise intervention to restore limb symmetry, and to analyze the relationship between biomechanical limb symmetry and quadriceps strength symmetry. It was found that compared to healthy individuals, patients that received the NMES-only, eccentric-only, or standard of care interventions displayed a significantly lower limb symmetry index (i.e. greater bilateral difference) in knee extension moment during a single-legged landing task (Table 2, Figure 3). Knee flexion angles did not appear to be as affected as knee extension moment post-ACL reconstruction, as no significant group differences were identified (Table 2, Figure 4). Lastly, quadriceps strength symmetry was found to be significantly related to limb symmetry for sagittal plane mechanics, suggesting that if quadriceps strength is improved in the ACL reconstructed limb, sagittal plane biomechanics will be positively affected (Figures 5 and 6). Though our combined NMES and eccentric exercise intervention was found to be most closely related to our Healthy group (Table 2), differences in biomechanical limb symmetry index still existed to some extent. Taken together, this finding indicates that knee joint function is not fully restored with this combined therapeutic approach at the time patients returned to activity.

4.1.1 Knee mechanics

Individuals that were exposed to the combined intervention (NMES&ECC) were able to generate knee moments that most closely resemble their non-injured limb, whereas patients that received the standard of care, NMES-only or eccentrics-only demonstrated significantly less limb symmetry. This difference was driven by reduced knee extension moments with the reconstructed limb (Table 2 and Figure 3). The combined group (NMES&ECC) observationally displayed reduced limb symmetry for knee extension moments that was found to be clinically meaningful, but not statistically different from Healthy individuals. This result suggests that although the combined intervention was the most successful at reinstituting limb symmetry, alterations in knee extension moments still existed to some extent. Importantly, compared to all our ACL reconstructed patients, our Healthy group displayed very high limb symmetry indices (small inter-limb alterations) for knee mechanics, which is in agreement with previous research suggesting that there is no difference between limbs in healthy individuals during activity (Button et al., 2005). As such, inter-limb differences in knee mechanics, that reduced limb symmetry, appear to be a characteristic that was specific only to our ACL reconstructed patients, suggesting that an incomplete recovery of knee function existed at return-to-activity.

Surprisingly, though our combined group (NMES&ECC) demonstrated a biomechanical knee extension limb symmetry index that was not statistically different than Healthy, the eccentric-only group did not exhibit the same trend. This finding is in contrast to our hypothesis, as we had anticipated that participants who received the eccentric exercise intervention would respond similarly. To our knowledge, Coury et al. (2006) is the only other study to have examined alterations in knee kinematics post-reconstruction after the application of an eccentric exercise intervention. In this cohort (Coury et al., 2006), it was observed that knee flexion improved from baseline (pre: 51° post: 58°) during level ground walking (5.0 km/h) following a 12-week eccentric exercise intervention in five male individuals that were approximately nine months post-surgery. Though this is a relatively small sample (Coury et al., 2006), and there is limited data on this topic, we had anticipated that our patients would respond similarly. From a clinical standpoint, given that the main function of the quadriceps muscle is eccentric actions (ex. controlled deceleration of the body during weight bearing), we had anticipated that participants who trained eccentrically would be better able to utilize their quadriceps muscle during activity and would therefore demonstrate more symmetrical sagittal plane knee movement. Although it is not entirely clear as to why the eccentric-only group demonstrated reduced limb symmetry for knee extension moment as compared to the combined group (NMES&ECC), there are a couple of plausible explanations. One possibility is that exposure to the eccentric exercise treatment did not transfer to a more efficient utilization of eccentric muscle actions during the hopping task. In other words, there may have been a lack of a transfer or motor-learning effect. Similar to our work, others have found that strength training alone is not sufficient to alter lower extremity jump landing mechanics (Herman et al., 2008). Specifically, it is thought that in addition to muscle strengthening, rehabilitation programs should include a neuromuscular component to positively influence lower extremity mechanics (Myer et al., 2005). Thus, it seems plausible that the combination of NMES and eccentric exercise may have been more effective, as a variety of modalities that are able to target both the strength as well as the neural components of muscle may have been able to better augment movement, and promote utilization of the quadriceps muscle during activity (Herman et al., 2008). Interestingly in a rodent model, NMES interventions following ACL transection have recently been found to help mitigate muscle atrophy (Durigan et al., 2014a) and promote beneficial adaptations to the quadriceps extracellular matrix by reducing the formation of fibrotic tissue following ACL injury (Durigan et al., 2014b). Thus the underlying benefits of NMES may not yet be well understood. Despite the fact that our previous work indicates that NMES does not significantly improve the recovery of muscle strength or neural activity after ACL reconstruction,(Lepley et al., 2015) animal models indicate that NMES may provide other beneficial results to the muscle tissue that have the potential to translate to improved muscle function/movement, which we have yet to investigate in a clinical population. Future work in humans is needed to confirm or refute these results. Another possibility is that there was a psychological component to this single-legged hopping activity, and that individuals placed into the eccentric-only group were simply not as comfortable performing this activity as others, despite the fact that they had a similar quadriceps strength index to group NMES&ECC (Table 3). This potential fear of re-injury is common post-ACL reconstruction (Langford et al., 2009) and is associated with reduced function (Chmielewski et al., 2008). As such, this potential psychological factor could have resulted in the eccentric group utilizing less quadriceps function, resulting in a lower knee extension moment and larger inter-limb difference. Importantly, in addition to improving muscle function, NMES has also been found to improve patient self-reported function (Fitzgerald et al., 2003), which in turn may have also helped to improve performance during our dynamic landing task. Ultimately, our work provides some preliminary data, and indicates that an eccentric intervention with a neural component such as NMES is beneficial at improving knee mechanic limb symmetry post-reconstruction. Given the results of this study and the limited research to date, more work is needed.

Interestingly, no significant difference was found in the limb symmetry index for knee flexion angles, though it appears that the NMES-only group tended to have lower limb symmetry (i.e. reduced length of time and/or magnitude of knee flexion) as compared to healthy controls for this measure (P=0.08, d=1.47, CI=0.49, 2.46, Table 2). As such, it appears that our individuals with ACL reconstruction were able to maintain knee flexion angles that were similar to their non-injured knee, despite the fact that deficits in knee extension moments were identified. To accomplish this movement pattern, it is possible that our ACL participants may have adopted a forward trunk lean during landing. In this scenario, by leaning the body’s center of mass anteriorly, the ground reaction force would have been repositioned closer to the knee joint complex, resulting in a smaller moment arm and a consequent reduction in the knee extension moment (Winter, 2005). This alteration in trunk flexion, leading to reduced knee extension moments and stable knee flexion angles, has recently been identified in patients with ACL reconstruction during a single-legged-forward-hop task (Oberländer et al., 2013), that is similar to the one employed in this study. As such, it seems likely that our patients may have utilized a forward trunk lean to reduce the strain on the quadriceps muscle, which resulted in a lower knee extension moment that reduced the limb symmetry index. However, due to the fact that our biomechanical model did not include a trunk segment, we cannot say with certainty that our patients adopted this movement pattern. Future work should take these biomechanical model components into consideration. Alternatively it also seems plausible our patients may have utilized the “quadriceps avoidance” pattern during landing in an attempt to reduce anterior shear gait loading during tasks. This quadriceps avoidance pattern is characterized by reduced knee extension moments in combination with greater knee flexion angles, which in part, is that is thought to result from persistent muscle inhibition, pain and/or swelling following ACL reconstruction (Devita et al., 1997). Though our previous work indicates that our patients returned to activity with relatively low levels of persistent muscle inhibition (central activation rations ranged:~92-98%), we did not objectively quantify pain or persistent swelling (Lepley et al., 2015). Thus, it still seems plausible that patients may have adopted this “quadriceps avoidance” motor pattern in an attempt to protect the graft after surgery due to ongoing pain from the donor graft cite or persistent joint effusion.

4.1.2 Relationship between quadriceps strength and knee mechanics

Individuals with less side-to-side strength deficits were able to demonstrate movement patterns that more closely resemble their non-injured limb (Figures 5 and 6). This result supports our hypothesis, and is in agreement with previous literature (Lewek et al., 2002; Oberländer et al., 2013; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991), indicating that alterations in knee mechanics are in part due to residual muscle weakness. Similar to our work, Oberländer and colleagues (2013) found that at 12-months post-reconstruction, deficits in quadriceps strength assessed via MVIC were significantly correlated with reduced knee extension moments during their single-legged hopping task. This relationship has also been corroborated by Lewek et al. (2002) and Snyder-Mackler et al. (1991). Specifically, Lewek et al. (2002) found that patients with a greater recovery of quadriceps strength post-reconstruction were able to produce knee extension moments and angles that were indistinguishable from healthy controls and were significantly correlated with quadriceps strength during walking and jogging activities. Likewise, Snyder-Mackler et al. (1991) noted that patients with stronger quadriceps muscles post-reconstruction demonstrated more normal gait patterns with greater flexion-excursion gait patterns that were correlated with strength. Importantly our data indicates that only about 20% of the variability in knee joint moments and angles can be explained by the quadriceps index. As such, though improvements in quadriceps strength will likely improve knee mechanics, alterations in moment patterns are likely due to a combination of events such as alterations in neural activity and/or motor learning patterns, psychological readiness, as well as joint kinematics/kinetics of both the upper and lower kinetic chains. Notably, it should be highlighted that some patients displayed extremely low quadriceps indexes (~60%) at a time point when they were returned-to-activity (Figures 5 and 6). Given the hazardous consequences of persistent quadriceps weakness on long-term knee joint health (Keays et al., 2010; Tourville et al., 2014), as well as the relationship between quadriceps strength asymmetry and biomechanical asymmetry identified in this manuscript and supported by others (Lewek et al., 2002; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991), these data further emphasize the need for clinicians and research to find therapeutic approaches capable of improving the recovery of strength. Further these data seems to suggest that there may be a need to delay decisions for return-to-activity until better quadriceps strength is achieved.

4.1.3 Limitations

The use of contralateral limb as a control may have resulted in alterations in the limb symmetry index calculations. Although we do recognize that this is an imperfect method, given the potential for alterations in the neuromuscular function in the non-injured limb post-ACL injury (Hiemstra et al., 2007), this data analysis technique has previously been employed by several studies investigating the motion of the ACL deficient (Li et al., 2006) and reconstructed knee (Deneweth et al., 2010; Oberländer et al., 2013; Papannagari et al., 2006; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991). Furthermore, work by Teichtahl et al. (2009) has shown that inter-subject variability exceeds that of intra-subject variability with regards to knee mechanics, as such we believe that the use of the contralateral limb to calculate limb symmetry was justified. Additionally, our biomechanical model did not include a trunk segment. Therefore we can only speculate that our ACL patients may have utilized a forward trunk lean to maintain knee flexion angles with a concurrent reduced knee extension moment. Further, this investigation utilized a mixed cohort of patients, including two graft types and patients that underwent a variety of concomitant meniscal procedures (Table 1). Due to the small group sample size, this investigation was not adequately powered to analyze these potential covariates as factors that may have altered sagittal plane knee mechanics. In our own work, we have found that concomitant meniscectomy and/or meniscal repair does not lead to greater quadriceps strength deficits than isolated ACL reconstruction (Lepley et al., 2014). Moreover, at this point in time, it appears that both the patellar-tendon and hamstring graft type produce similar function results (Mohtadi et al., 2011) and knee mechanics (Tashman et al., 2007). However, we do acknowledge that alterations in surgical produces between graft type and meniscal injuries may have been a factor that influences our results. Future work should take these limitations into consideration.

4.1.4 Clinical implications

In ACL rehabilitation, restoring strength and bilateral limb symmetry is a primary clinical goal as asymmetries and strength deficits are thought to increase the risk of contralateral and ipsilateral limb injury (Paterno et al., 2010; Schmitt et al., 2012). It is therefore concerning that biomechanical limb asymmetry was common among our patients with ACL reconstruction at return-to-activity. Though it was found that the NMES&ECC did not display biomechanical limb symmetry alterations as compared to Healthy, group NMES&ECC still displayed alterations in knee mechanics (biomechanical limb symmetry index: moment=66%, angle=92%), and quadriceps strength (QI=85%) below what is deemed ideal after ACL reconstruction (QI>90%). Based on these results, a longer eccentric intervention post-reconstruction may be beneficial, as this therapy was found to be the driving factor behind strength gains in our previous work (Lepley et al., 2015). Additionally of the ACL patients in our study, those individuals with less side-to-side strength deficits were able to demonstrate movement patterns that more closely resemble their non-injured limb. This result is in agreement with the previous literature (Lewek et al., 2002; Oberländer et al., 2013; Snyder-Mackler et al., 1991) and indicates that interventions that are capable of improving quadriceps strength, such as the one employed in this current study, should positively improve dynamic movement in ACL reconstructed patients. Further, animal models seem to indicate that NMES may have some underlying neuromuscular benefits that promote muscle function (Durigan et al., 2014a; Durigan et al., 2014b), which in turn may lead to improved performance during dynamic tasks. Future work studying the ability of NMES to mitigate harmful alterations in muscle morphology in a clinical population seems justified to understand the full benefits of this type of therapeutic intervention.

5.1 Conclusion

A combined NMES and eccentric exercise intervention was found to restore biomechanical limb symmetry that was most closely related to Healthy individuals following ACL reconstruction at a time when patients were returned to participation. Greater knee flexion angles and moments over stance were related to quadriceps strength, suggesting that interventions capable of restoring quadriceps strength can positively influence sagittal plane knee mechanics, which should help to improve functional performance post-reconstruction.

Supplementary Material

Manuscript Highlights.

Combined neuromuscular electrical stimulation and eccentric exercise intervention was capable of restoring biomechanical symmetry that was most similar to healthy individuals at 7 months following ACL reconstruction.

Longer eccentric intervention may be beneficial, as this therapy was found to be the driving factor behind strength gains in our previous work, and greater quadriceps symmetry were able to demonstrate greater biomechanical limb symmetry.

This study helps to provide preliminary evidence of therapies that positively affect influence movement post-ACL reconstruction. However, to determine the true clinical effect, larger sample sizes and patient randomization is needed.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number K08 AR05315201A2 to Dr. XXXXX. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: We certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on us or on any organization with which we are associated. No conflicts of interest are directly relevant to the content of this study.

References

- Andriacchi TP, Birac D. Functional testing in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Clin Orthop. 1993:40–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borotikar BS, Newcomer R, Koppes R, McLean SG. Combined effects of fatigue and decision making on female lower limb landing postures: central and peripheral contributions to ACL injury risk. Clin Biomech. 2008;23:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button K, van Deursen R, Price P. Measurement of functional recovery in individuals with acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39:866–871. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.019984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski TL, Jones D, Day T, Tillman SM, Lentz TA, George SZ. The association of pain and fear of movement/reinjury with function during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:746–753. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski TL, Rudolph KS, Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Biomechanical evidence supporting a differential response to acute ACL injury. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2001;16:586–591. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski TL, Stackhouse S, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A prospective analysis of incidence and severity of quadriceps inhibition in a consecutive sample of 100 patients with complete acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:925–930. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cole GK, Nigg BM, Ronsky JL, Yeadon MR. Application of the joint coordinate system to three-dimensional joint attitude and movement representation: a standardization proposal. J Biomech Eng. 1993;115:344–349. doi: 10.1115/1.2895496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coury HJ, Brasileiro JS, Salvini TF, Poletto PR, Carnaz L, Hansson GA. Change in knee kinematics during gait after eccentric isokinetic training for quadriceps in subjects submitted to anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Gait Posture. 2006;24:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong SN, van Caspel DR, van Haeff MJ, Saris DBF. Functional assessment and muscle strength before and after reconstruction of chronic anterior cruciate ligament lesions. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster WT, Gabel WC, Felts WJL. The anthropometry of the manual work space for the seated subject. American journal of physical anthropology. 1959;17:289–317. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330170405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneweth JM, Bey MJ, McLean SG, Lock TR, Kolowich PA, Tashman S. Tibiofemoral joint kinematics of the anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knee during a single-legged hop landing. The American journal of sports medicine. 2010;38:1820–1828. doi: 10.1177/0363546510365531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita P, Hortobagyi T, Barrier J. Gait biomechanics are not normal after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and accelerated rehabilitation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998a;30:1481–1488. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devita P, Hortobagyi T, Barrier J, Torry M, Glover KL, Speroni DL, Money J, Mahar MT. Gait adaptations before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:853–859. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199707000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita P, Lassiter T, Hortobagyi T, Torry M. Functional knee brace effects during walking in patients with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The American journal of sports medicine. 1998b;26:778–784. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durigan J, Delfino GB, Peviani SM, Russo TL, Ramirez C, Silva Gomes A, Salvini TF. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation alters gene expression and delays quadriceps muscle atrophy of rats after anterior cruciate ligament transection. Muscle & Nerve. 2014a;49:120–128. doi: 10.1002/mus.23883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durigan J, Peviani S, Delfino G, de Souza José R, Parra T, Salvini T. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Induces Beneficial Adaptations in the Extracellular Matrix of Quadriceps Muscle After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Transection of Rats. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2014b doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000110. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer GB, Davis SE. ACSM's health-related physical fitness assessment manual. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. A modified neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocol for quadriceps strength training following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:492–501. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.9.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber JP, Marcus RL, Dibble LE, Greis PE, Burks RT, Lastayo PC. Safety, feasibility, and efficacy of negative work exercise via eccentric muscle activity following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:10–18. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2007.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JM, Ko J-WK, Konold T, Pietrosimione B. Sagittal plane knee joint moments following anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction: a systematic review. Clin Biomech. 2010;25:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman DC, Weinhold PS, Guskiewicz KM, Garrett WE, Yu B, Padua DA. The effects of strength training on the lower extremity biomechanics of female recreational athletes during a stop-jump task. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:733–740. doi: 10.1177/0363546507311602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog W, Longino D, Clark A. The role of muscles in joint adaptation and degeneration. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;388:305–315. doi: 10.1007/s00423-003-0402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiemstra LA, Webber S, MacDonald PB, Kriellaars DJ. Contralateral limb strength deficits after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using a hamstring tendon graft. Clin Biomech. 2007;22:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley MV. The role of muscle weakness in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999;25:283–298. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70068-5. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keays SL, Newcombe PA, Bullock-Saxton JE, Bullock MI, Keays AC. Factors involved in the development of osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. The American journal of sports medicine. 2010;38:455–463. doi: 10.1177/0363546509350914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford JL, Webster KE, Feller JA. A prospective longitudinal study to assess psychological changes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;43:377–378. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.044818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepley LK, Wojtys EM, Palmieri-Smith RM. Does Concomitant Meniscectomy or Meniscal Repair Affect the Recovery of Quadriceps Function Post-ACL Reconstruction? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3093-3. Epud ahead of print (online published) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepley LK, Wojtys EM, Palmieri-Smith RM. Combination of Eccentric Exercise and Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation to Improve Quadriceps Function Post-ACL Reconstruction. The Knee. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.11.013. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewek M, Rudolph K, Axe M, Snyder-Mackler L. The effect of insufficient quadriceps strength on gait after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech. 2002;17:56–63. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Moses JM, Papannagari R, Pathare NP, DeFrate LE, Gill TJ. Anterior cruciate ligament deficiency alters the in vivo motion of the tibiofemoral cartilage contact points in both the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 2006;88:1826–1834. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SG, Felin RE, Suedekum N, Calabrese G, Passerallo A, Joy S. Impact of fatigue on gender-based high-risk landing strategies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:502–514. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180d47f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SG, Huang X, Su A, Van Den Bogert AJ. Sagittal plane biomechanics cannot injure the ACL during sidestep cutting. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2004a;19:828–838. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SG, Huang X, Van Den Bogert AJ. Association between lower extremity posture at contact and peak knee valgus moment during sidestepping: implications for ACL injury. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2005;20:863–870. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SG, Lipfert SW, Van Den Bogert AJ. Effect of gender and defensive opponent on the biomechanics of sidestep cutting. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2004b;36:1008. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000128180.51443.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohtadi NG, Chan DS, Dainty KN, Whelan DB. Patellar tendon versus hamstring tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament rupture in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:9. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005960.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer GD, Ford KR, Brent JL, Hewett TE. Differential neuromuscular training effects on ACL injury risk factors in"high-risk" versus "low-risk" athletes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer GD, Ford KR, Palumbo OP, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training improves performance and lower-extremity biomechanics in female athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2005;19:51–60. doi: 10.1519/13643.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes FR, Barber SD, Mangine RE. Abnormal lower limb symmetry determined by function hop tests after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:513–518. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberländer KD, Brüggemann G-P, Hoeher J, Karamanidis K. Altered landing mechanics in ACL-reconstructed patients. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2013;45:506–513. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182752ae3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri-Smith RM, Thomas AC, Wojtys EM. Maximizing quadriceps strength after ACL reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27:405–424. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papannagari R, Gill TJ, DeFrate LE, Moses JM, Petruska AJ, Li G. In Vivo Kinematics of the Knee After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction A Clinical and Functional Evaluation. The American journal of sports medicine. 2006;34:355–360. doi: 10.1177/0363546506290403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Huang B, Hewett TE. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1968–1978. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt LC, Paterno MV, Hewett TE. The Impact of Quadriceps Femoris Strength Asymmetry on Functional Performance at Return to Sport Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42:750–759. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder-Mackler L, Ladin L, Schepsis AA, Young JC. Electrical stimulation of the thigh muscles after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1025–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashman S, Kolowich P, Collon D, Anderson K, Anderst W. Dynamic function of the ACL-reconstructed knee during running. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;454:66–73. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31802bab3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichtahl AJ, Wluka AE, Morris ME, Davis SR, Cicuttini FM. The associations between the dominant and nondominant peak external knee adductor moments during gait in healthy subjects: evidence for symmetry. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2009;90:320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourville TW, Jarrell KM, Naud S, Slauterbeck JR, Johnson RJ, Beynnon BD. Relationship Between Isokinetic Strength and Tibiofemoral Joint Space Width Changes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:302–311. doi: 10.1177/0363546513510672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster KE, Gonzalez AR, Feller JA. Dynamic joint loading following hamstring and patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigerstad-Lossing I, Grimby G, Jonsson T, Morelli B, Perterson L, Renstrom P. Effects of electrical muscle stimulation combined with voluntary contractions after knee ligament surgery. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20:93–98. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198802000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson JD, Davis IS. Lower extremity mechanics of females with and without patellofemoral pain across activities with progressively greater task demands. Clin Biomech. 2008;23:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter DA. Biomechanics and motor control of human movment. Third Wiley and Sons Publishers; New Jersey: 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.